Yeah, same, I like it because it's a really simple premise, Shuttle start and N1 cancellation were events separated by ~2 years, the former happening without the latter inevitably results in the USSR keeping a capability that the US abandonned and have no other choice but regaining it, with many years of delay. There's really no other way it could go. It's simple and the results are methodical. This timeline does it very well.I do like this TL for exploring the idea of the Soviets leapfrogging the US, that was their idea OTL until Glusko canned it due to the N1 failures, and likely a personal grudge against Korolev, then the US made a shuttle and the soviets were convinced it was a bomber (theoretically it was capable of this) that could decapitate the government without warning, as the ICBM and SLBM (and other various BM's) radars faced Europe and North, with a handful at other nuclear powers like Isreal, China and Inda and Pakistan

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A Sound of Thunder: The Rise of the Soviet Superbooster

- Thread starter nixonshead

- Start date

IIRC before and after Columbia NASA was buying up old computers from the 70s for spare parts, as the manufacturers had moved on a long time beforehand, Apollo would be the same, the manufacturers warned when the last Saturn stage was complete that the government had 2 years to decide to restart the line. Considering the last stage was finshed in 69 (if im not mistaken), had the soviets landed a day after 17 left, NASA would have a huge expense just getting the assembly line built. not to mention restarting the LM and CSM lines, plus all the contractors and stuffYeah, same, I like it because it's a really simple premise, Shuttle start and N1 cancellation were events separated by ~2 years, the former happening without the latter inevitably results in the USSR keeping a capability that the US abandonned and have no other choice but regaining it, with many years of delay. There's really no other way it could go. It's simple and the results are methodical. This timeline does it very well.

There is a reason why Obama canned Constellation for Commerical Crew, then Congressmen and woman made a new launcher SLS (Senate Launch System) so the 100k jobs arn't lost, which at the end of the day, Apollo, Shuttle, SLS, Mercury and Gemini were all jobs program's and were purposly policical, the fact they resulted in flights and moonlandings were byproducts

Anybody and i mean ANYBODY who thinks countries fly spaceflights for exploration (outside of probes and such) is not aware of the underlying politics

I think this is supposed to be Ken Mattingly speaking here.

Interlude: Burn-Through

===

“They should be, but I checked with Jack this afternoon. The STS-4C and -5 launch readiness reports make no mention of this issue. Marshall hasn’t even assigned it a formal tracking number! I took it to Chet, but he said to leave it with the experts at Marshall.” Frank paused to take another gulp of beer before continuing. “I mean, he’s probably right, the risk of a total burn-though is minimal. But dammit Frank, that was Hal’s and my ass on the line on STS-3! At the very least, Jack and his crew deserve to know about it before they go up.”

The first Skylab is referred to retrospectively as Skylab-A ITTL.Wow! Can't wait to see that thing in space as well, hope it ends up doing a little bit better than Buran did irl (though I doubt we're going to get the Baikal equivalent of The Snow Flies here).

Unrelated side thought, but I was thinking, if Skylab-B does end up serving as the basis for an expanded station later, I think it will just be remembered as "Skylab", with the first station, seen more as an early step/prototype, will be retroactively called Skylab 1 or Skylab A. Sort of like what will probably happen with Tiangong right now.

Is that a folding wing design?

Oh dear

Beautiful render though. Well done.

The design of Baikal is basically ripped off from the Convair FR-3 orbiter proposed for the space shuttle. It had the characteristics needed to put it on top on N-1, while still having a validated re-entry and flyback concept.Swing-wing with the wings retracted into the fuselage to protect them from reentry. US had a similar designs including a version of the Starclipper and the General Dynamics Tri-Mese concept. The wings are not really 'adjustable' on the operational model, probably just extended or retracted with a robust screw type deployment system rather than actually "variable' sweep.

Randy

Original intent was for the image to show take-off, but given the angle of attack, I’d say it looks more like landing.Given the state of the Soviet Economy at this time - and Reagan's policies not helping them any - I'm not seeing too many flights of Baikal...

Love the render though. Is that during take-off? Or landing?

Buran’s heatshield was fully reusable (or as fully as STS’s was). Baikal’s is… nearly fully reusable, as we’ll see in the next post.Is the heat shield on Baikal reusable, iirc Burans had to be replaced (or would have been) after every flight

…

Nixonhead is Gorbachev still leader or was he butterflied out?

Gorbachev is coming. I had a look into butterflying this, but (from my limited research), I didn’t see a plausible alternative based on an improved Soviet space programme. The people it would mostly have benefitted (Ustinov, maybe Gromyko) were old guard and/or uninterested in the top job, and I didn’t see the changes I’d made as impacting the basic dynamic of a push for a ‘moderniser’ after a string of decrepit Stalin survivors.

Quite right, I’ve gone back and edited it. Thanks for the catch!I think this is supposed to be Ken Mattingly speaking here.

Part 2 Post 6: Hurricane

Post 6: Hurricane

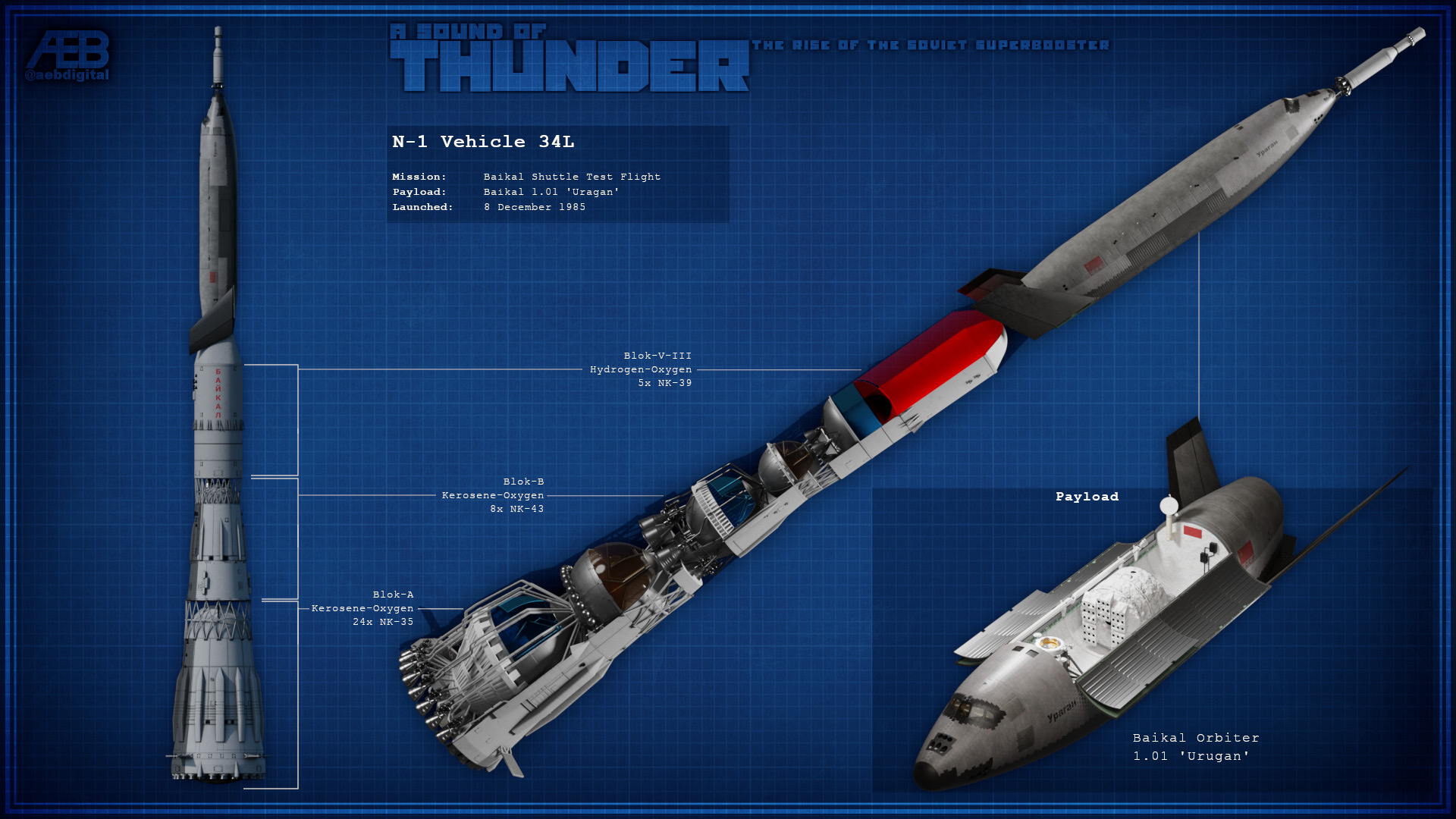

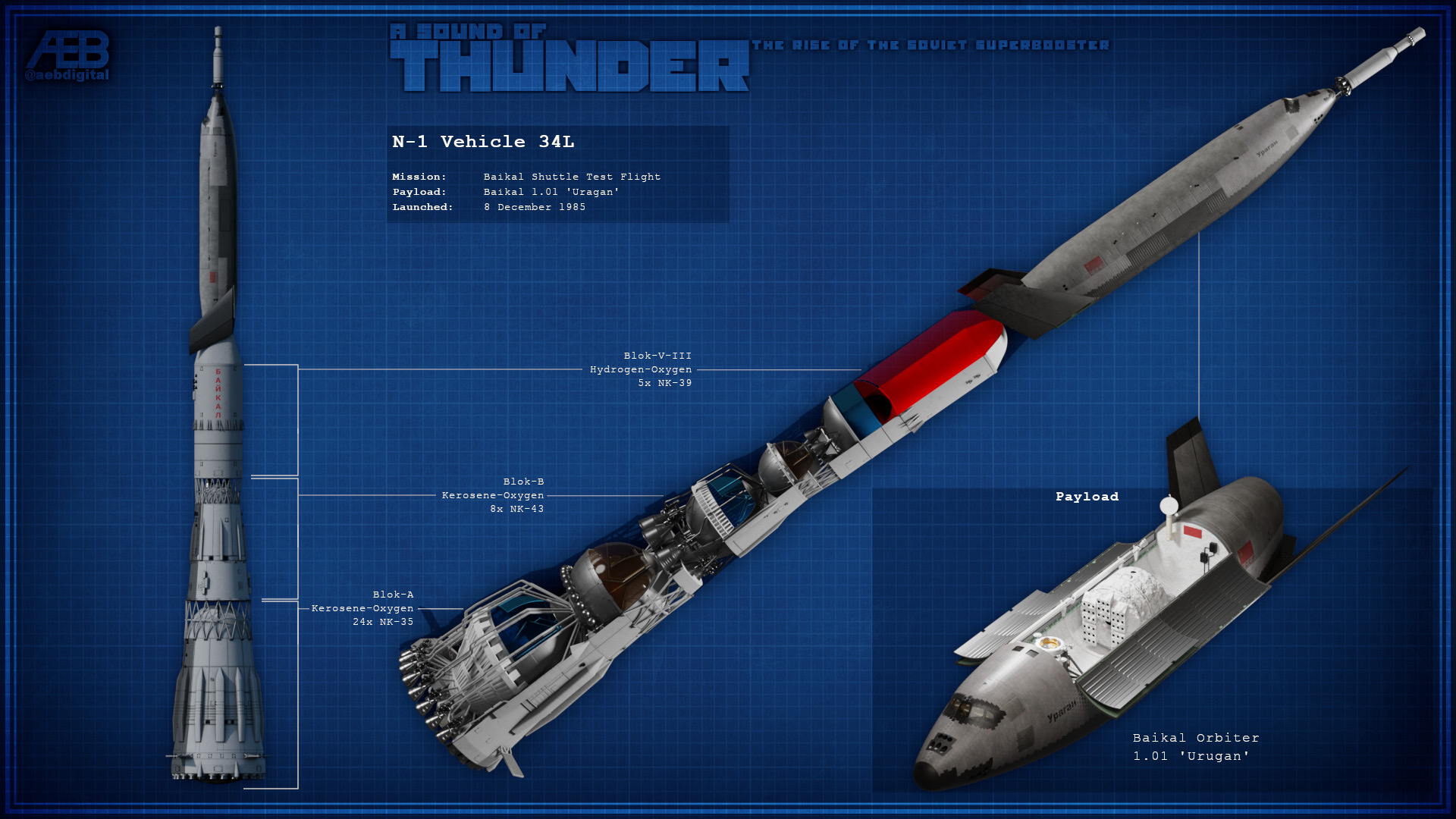

As part of its efforts to militarize space, the USSR has pressed forward with an active research and development program, centered at Tyuratam, to deploy increasingly capable space-based reconnaissance and surveillance satellites as well as space-based military communications systems. Soviet achievements in manned space operations are typified by their ongoing ZVEZDA lunar landing missions, their continued use of the ZARYA-3 military space station and development of their soon-to-be tested space shuttle, seen here mated to the heavy-lift launch vehicle.

- Soviet Military Power, 1984, US Government Printing Office

++++++++++++++++++++

Following formal approval of the programme in 1976, the Soviet shuttle effort quickly split into two parallel branches for the launch vehicle and the orbiter.

The most straightforward of the two was the N-1 upgrade effort, led by TsKBEM (re-named NPO Groza in 1980). The most significant aspect of this change was the development of the large Blok-V-III hydrogen-oxygen upper stage, which would replace the old kerolox Blok-V of the basic Groza. Building on the work done for the hydrolox Blok-Sr, and without the requirement for reusability that had caused such headaches for the Americans in developing the Space Shuttle Main Engine, development of the Blok-V-III proceeded relatively smoothly. Ground testing of the RD-37 engine started in 1980, with an integrated stage completing structural tests in 1982. Upgrades to the Blok-A and Blok-B stages were also made, mainly to strengthen them for their heavier load, but also to modernise the avionics systems, and to incorporate Kuznetsov’s uprated NK-33 derived engines, the NK-35. These new engines increased the thrust of the basic NK-33 to the point where the central six Blok-A engines could be removed, bringing the total first stage engine count back down to 24, as originally conceived by Korolev. With the necessary launch pad modifications having been completed the previous year, by the end of 1982 Mishin had everything he needed for a full-up test of the upgraded N1-OK stack. Everything, that is, except for a payload.

Development of the Baikal orbiter proved far more troublesome than its launcher. Although the selection of a simple cylindrical body with deployable wings avoided many of the hypersonic aerodynamics and wing shape optimisation problems that had plagued the US Shuttle, it also meant that there was no existing body of knowledge that could be drawn upon. No-one had ever tried to perform a controlled re-entry with such a large, wingless object, so Gleb Lozino-Lozinskiy’s team at NPO Molniya had to start from first principals.

A particular problem was the accurate modelling of the thermal environment that would be experienced by the shuttle on re-entry. A number of sub-scale models of the basic Baikal shape were flown into orbit between 1978 and 1981 to get a better understanding of these issues, with the results revealing an even more challenging environment than had been initially anticipated. This required a significant amount of re-work on the thermal protection tiles being developed for the craft, and led to the adoption of a hybrid ablative-insulation system that incorporated an outer coating that would burn away during the hottest parts of re-entry before exposing the underlaying insulating tiles. Together with the use of an active cooling system to transfer heat away from the nose, this appeared to solve the re-entry problem, but led to significant delays and budget overruns for the orbiter.

While Molniya were still trying to solve the thermal problems, they nevertheless managed to ship the OK-ML1 structural test article and OK-MT engineering mockup, to Baikonur in June 1981. In addition to supporting load tests of the Baikal airframe, these test vehicles were used by both Mishin and Barmin’s teams to perform fit checks and develop launch processing procedures that would be used on the real shuttle. These culminated in September 1982 with the roll-out of a complete N1-OK stack to Pad 38, with the OK-ML1 vehicle mounted atop the rocket. The stack stayed at the pad for two months of integration testing, before being rolled back to the assembly building. Similar tests, with increasing fidelity, would be performed over the next two years.

A major milestone came in May 1983, with the start of atmospheric flight tests at the Zhukovsky air base. As the Soviet Union lacked a carrier aircraft big enough to duplicate the Approach and Landing Tests undertaken by the Americans, these test flights instead used a specialised variant of the orbiter, designated OK-GLI, but unofficially known as “the Flying Pencil”. OK-GLI was an aerodynamic copy of the planned orbiter, but with dummy thermal protection tiles and sporting an additional two AL-31F jet engines. These supplemented the twin deployable engines that Baikal would normally carry to allow it to take off under its own power. For the initial series of test flights, the Baikal’s wings were fixed in place, but OK-GLI was further modified in 1984 to include a variable-geometry capability. The second series of test flights tested this capability, culminating in a daring full retraction-and-redeployment test from 8000m in late 1984.

However, just as the atmospheric test flights began demonstrating tangible progress on the Baikal orbiter, the N-1 launcher suffered a setback in September with the failure of the first test launch of the uprated booster. Mishin had continued to eschew expensive integrated ground tests in favour of the all-up flight test approach that had served him on the original N-1 development programme and, as on that original programme, this resulted in an early failure. This was the first time that the NK-35 engined, Blok-V-III 3rd stage, and a representative Baikal test orbiter (OK-ML2) had been launched, and the combination set up the conditions for a destructive “pogo” effect as Blok-B staging approached. Violent oscillations in the stack ruptured a fuel line in Blok-B, triggering an explosion as the stage ignited that took out the whole stack.

The failure was kept from the public, and Mishin tried to dismiss it as the normal teething problems of a new launcher, but it caused some concern amongst the leadership. The war in Afghanistan and unrest in Poland were running sores for the new administration of Yuri Andropov, while the Americans under Reagan were becoming more assertive and aggressive. Space remained one of the few arenas in which the USSR enjoyed a favourable public image, both internally and internationally, but the Baikal project in particular was consuming huge resources for little visible progress - resources that were becoming ever-more scarce in the Soviet Union. With the US Space Shuttle now appearing to be less of a military threat than had first been feared, questions were starting to be asked as to whether it was really necessary to run an expensive shuttle project in parallel to an expansive lunar programme.

Fortunately for Mishin, these questions remained subdued for the next few years, as the Soviet leadership was preoccupied with the deaths in rapid succession of Brezhnev, Andropov and Chernenko. By the time Mikhail Gorbachev was confirmed as Secretary-General in March 1985, Mishin was able to point to a successful N1-OK stack launch the previous September, and advanced preparations for another test flight in the summer that would demonstrate the Baikal launch escape system. Together with the foreign policy coup of the Zvezda 10 lunar mission in February, these tangible signs of progress put Mishin in good odour with the new administration.

The escape system test launch took place in July, and saw the cockpit of the OK-ML4 test article pulled free of the stack at an altitude of 10km, stabilise itself via integrated body flaps, then descend under parachutes for a hard-but-survivable landing in eastern Kazakhstan. The test was a success, despite the fact that two NK-35s failed on the Blok-A, leading to a loss of four out of the 24 first stage engines. The cause was later traced to a processing error during launch preparations, due in part to the punishing schedule of four N-1 launch campaigns within a year, and the confusion of concurrently processing N1F and N1-OK variants for Zvezda and Baikal missions. Ironically, this failure would probably have led to an abort had it occurred on a real launch, although the abort scenario in that case would have been to separate the entire Baikal orbiter after Blok-A depletion, followed by a glide back to Baikonur or a landing at the Ukrainka Air Base in the far eastern Amur Oblast.

With the campaign of orbiter atmospheric test flights completing in October 1985, preparations began to mate Baikal orbiter 1.01, the first flight model, to its N1-OK launcher for the first orbital test launch. Still scarred by the memory of the death of Komarov on Soyuz 1, Mishin agreed that the shuttle would launch without a crew for this first test, and in fact this would prove advantageous for other reasons. Without a crew on board, there was no need to complete installation of the complicated life support equipment that would otherwise be needed. Electrical power consumption would therefore also be greatly reduced, which when taken together with a planned single-orbit mission, meant that the heavy thermal control radiators would not be needed. This saved many months of work in preparing the orbiter, allowing Mishin to advance the test flight schedule.

Following two on-pad aborts, the first launch of the Baikal shuttle orbiter, designated mission 1K1, finally occurred on 8th December 1985. N1-OK vehicle 34L successfully placed orbiter 1.01 into a 251 x 255km orbit at an inclination of 51.6°. The spacecraft orbited the Earth twice, keeping its payload bay doors closed, before automatically firing its manoeuvring engines and decelerating back into the atmosphere. The re-entry was a little rougher than anticipated, but the thermal protection systems worked well enough, slowing the ship sufficiently to allow for deployment of the wings and jet engines. Here the first major anomaly occurred, as one of the twin jets failed to start. The shuttle’s autopilot quickly recognised the failure, and throttled down the remaining engine, using the aerodynamic surfaces of the V-tail to compensate for the yaw induced by the asymmetrical thrust. The orbiter was able to limp back to the runway at Baikonur, guided by radio beacons to an automatic touchdown.

As soon as the shuttle was safely back on Earth, TASS made a public announcement of this new Soviet space triumph to the world. The fully automatic nature of the mission was particularly highlighted as something of which the American Shuttle was incapable. With earlier test launches of the N1-OK rocket already having been publicly identified as “Baikal”, the press release for the first time gave a separate name to the first Soviet shuttle orbiter: Uragan (Hurricane). Following a further series of uncrewed test flights that would fully demonstrate the capabilities of the new spacecraft (the press release went on), crewed missions would soon begin, confirming the USSR’s position as the globe’s dominant space power.

In fact there was still considerable work to be done to get Uragan ready for a crew, and it was more than a year until a second shuttle mission was ready for lift-off on 20th February 1987. This second mission, designated 2K1, was also launched without a crew, but it would not remain unoccupied for long. Two days after Uragan had reached orbit, a Vulkan rocket lifted off from Baikonur carrying the Slava 26 mission, crewed by cosmonauts Aleksey Boroday, Eduard Stepanov and Valeri Polyakov.

After a two day orbital chase, Slava 26 made a close rendezvous with Uragan, and began a careful flyaround inspection of the orbiting spaceplane. Uragan appeared to be in good health, with the payload bay doors and newly-installed radiators fully deployed. Most importantly for the mission, the Airlock and Docking Module in Uragan’s payload bay had its APAS-85 docking port fully extended. Derived from the androgynous docking system developed for the Apollo-Soyuz mission, the APAS would allow Uragan to dock with any similarly equipped vehicle, be it a space station, Slava spaceship, or even a future Zvezda-derived lunar ferry. This would give greater flexibility in planning space operations, as well as allowing for rescue missions at short notice. It was this last scenario that Slava 26 was intended to simulate. With the recent example of Challenger fresh in everyone’s mind, Mishin wanted to make sure he had a method of retrieving shuttle crews from orbit should something go wrong.

Boroday guided Slava to a textbook docking with Uragan, and the three cosmonauts were soon able to board the shuttle, entering through the airlock to the aft Work Compartment (RO). Here they made a quick visual inspection of Slava through the RO’s upper and aft windows, before proceeding through the hatch separating the main body of the shuttle from the detachable nose section to enter the ship’s flight deck, the Command Compartment (KO). While Stepanov continued to the lower Habitation Compartment (BO), Boroday and Polyakov began activating Uragan’s manual controls.

Slava 26 spent three days docked with Uragan, during which time the crew gave the shuttle’s systems a thorough check-out. This included a (very careful) activation of the twin SBM robotic arms to perform an inspection of the exterior of the shuttle. Although not able to see all of Uragan’s exterior (special booms to allow full coverage were not yet completed), this didn’t prevent TASS from touting this as yet another improvement of the Soviet shuttle over its American equivalent. In fact NASA would soon have the same ability as part of their post-Challenger upgrades, but this didn’t stop TASS claiming another first for the USSR.

After undocking from Uragan, the crew of Slava 26 travelled on to the Zarya 3 space station, while the shuttle made an automated reentry and landing. This time both AL-31F engines started correctly, powering Uragan to a controlled touch-down seven days after launch.

The Baikal test programme of just a few years earlier had called for an additional 2K1 class rendezvous mission and at least two unpiloted docking missions to Zarya before a crew would be launched aboard the shuttle. However, by 1987 Mishin’s budgets were being severely squeezed. The response to Reagan’s “Battlestar America” programme was absorbing huge volumes of resources, with the military’s attention and patronage shifting away from the shuttle towards laser battlestations and orbital weapons platforms. Both Baikal and the lunar base programme were forced to compete for funding with both Glushko’s space station ambitions and with one another. In the face of this squeeze, and with the success of the first two shuttle missions, Mishin ordered a shortening of the Baikal test programme. The second shuttle orbiter, vehicle 1.02, provisionally named “Tsiklon” (Cyclone), would be ready for launch in just a few months. The next time a Soviet shuttle took to the skies, Mishin decreed, there would be a crew aboard.

Last edited:

Great part.

Post 6: Hurricane

As part of its efforts to militarize space, the USSR has pressed forward with an active research and development program, centered at Tyuratam, to deploy increasingly capable space-based reconnaissance and surveillance satellites as well as space-based military communications systems. Soviet achievements in manned space operations are typified by their ongoing ZVEZDA lunar landing missions, their continued use of the ZARYA-3 military space station and development of their soon-to-be tested space shuttle, seen here mated to the heavy-lift launch vehicle.

- Soviet Military Power, 1984, US Government Printing Office

View attachment 879712

++++++++++++++++++++

Following formal approval of the programme in 1976, the Soviet shuttle effort quickly split into two parallel branches for the launch vehicle and the orbiter.

The most straightforward of the two was the N-1 upgrade effort, led by TsKBEM (re-named NPO Groza in 1980). The most significant aspect of this change was the development of the large Blok-V-III hydrogen-oxygen upper stage, which would replace the old kerolox Blok-V of the basic Groza. Building on the work done for the hydrolox Blok-Sr, and without the requirement for reusability that had caused such headaches for the Americans in developing the Space Shuttle Main Engine, development of the Blok-V-III proceeded relatively smoothly. Ground testing of the RD-37 engine started in 1980, with an integrated stage completing structural tests in 1982. Upgrades to the Blok-A and Blok-B stages were also made, mainly to strengthen them for their heavier load, but also to modernise the avionics systems, and to incorporate Kuznetsov’s uprated NK-33 derived engines, the NK-35. These new engines increased the thrust of the basic NK-33 to the point where the central six Blok-A engines could be removed, bringing the total first stage engine count back down to 24, as originally conceived by Korolev. With the necessary launch pad modifications having been completed the previous year, by the end of 1982 Mishin had everything he needed for a full-up test of the upgraded N1-OK stack. Everything, that is, except for a payload.

Development of the Baikal orbiter proved far more troublesome than its launcher. Although the selection of a simple cylindrical body with deployable wings avoided many of the hypersonic aerodynamics and wing shape optimisation problems that had plagued the US Shuttle, it also meant that there was no existing body of knowledge that could be drawn upon. No-one had ever tried to perform a controlled re-entry with such a large, wingless object, so Gleb Lozino-Lozinskiy’s team at NPO Molniya had to start from first principals.

A particular problem was the accurate modelling of the thermal environment that would be experienced by the shuttle on re-entry. A number of sub-scale models of the basic Baikal shape were flown into orbit between 1978 and 1981 to get a better understanding of these issues, with the results revealing an even more challenging environment than had been initially anticipated. This required a significant amount of re-work on the thermal protection tiles being developed for the craft, and led to the adoption of a hybrid ablative-insulation system that incorporated an outer coating that would burn away during the hottest parts of re-entry before exposing the underlaying insulating tiles. Together with the use of an active cooling system to transfer heat away from the nose, this appeared to solve the re-entry problem, but led to significant delays and budget overruns for the orbiter.

While Molniya were still trying to solve the thermal problems, they nevertheless managed to ship the OK-ML1 structural test article and OK-MT engineering mockup, to Baikonur in June 1981. In addition to supporting load tests of the Baikal airframe, these test vehicles were used by both Mishin and Barmin’s teams to perform fit checks and develop launch processing procedures that would be used on the real shuttle. These culminated in September 1982 with the roll-out of a complete N1-OK stack to Pad 38, with the OK-ML1 vehicle mounted atop the rocket. The stack stayed at the pad for two months of integration testing, before being rolled back to the assembly building. Similar tests, with increasing fidelity, would be performed over the next two years.

A major milestone came in May 1983, with the start of atmospheric flight tests at the Zhukovsky air base. As the Soviet Union lacked a carrier aircraft big enough to duplicate the Approach and Landing Tests undertaken by the Americans, these test flights instead used a specialised variant of the orbiter, designated OK-GLI, but unofficially known as “the Flying Pencil”. OK-GLI was an aerodynamic copy of the planned orbiter, but with dummy thermal protection tiles and sporting an additional two AL-31F jet engines. These supplemented the twin deployable engines that Baikal would normally carry to allow it to take off under its own power. For the initial series of test flights, the Baikal’s wings were fixed in place, but OK-GLI was further modified in 1984 to include a variable-geometry capability. The second series of test flights tested this capability, culminating in a daring full retraction-and-redeployment test from 8000m in late 1984.

However, just as the atmospheric test flights began demonstrating tangible progress on the Baikal orbiter, the N-1 launcher suffered a setback in September with the failure of the first test launch of the uprated booster. Mishin had continued to eschew expensive integrated ground tests in favour of the all-up flight test approach that had served him on the original N-1 development programme and, as on that original programme, this resulted in an early failure. This was the first time that the NK-35 engined, Blok-V-III 3rd stage, and a representative Baikal test orbiter (OK-ML2) had been launched, and the combination set up the conditions for a destructive “pogo” effect as Blok-B staging approached. Violent oscillations in the stack ruptured a fuel line in Blok-B, triggering an explosion as the stage ignited that took out the whole stack.

View attachment 879713

The failure was kept from the public, and Mishin tried to dismiss it as the normal teething problems of a new launcher, but it caused some concern amongst the leadership. The war in Afghanistan and unrest in Poland were running sores for the new administration of Yuri Andropov, while the Americans under Reagan were becoming more assertive and aggressive. Space remained one of the few arenas in which the USSR enjoyed a favourable public image, both internally and internationally, but the Baikal project in particular was consuming huge resources for little visible progress - resources that were becoming ever-more scarce in the Soviet Union. With the US Space Shuttle now appearing to be less of a military threat than had first been feared, questions were starting to be asked as to whether it was really necessary to run an expensive shuttle project in parallel to an expansive lunar programme.

Fortunately for Mishin, these questions remained subdued for the next few years, as the Soviet leadership was preoccupied with the deaths in rapid succession of Brezhnev, Andropov and Chernenko. By the time Mikhail Gorbachev was confirmed as Secretary-General in March 1985, Mishin was able to point to a successful N1-OK stack launch the previous September, and advanced preparations for another test flight in the summer that would demonstrate the Baikal launch escape system. Together with the foreign policy coup of the Zvezda 10 lunar mission in February, these tangible signs of progress put Mishin in good odour with the new administration.

The escape system test launch took place in July, and saw the cockpit of the OK-ML4 test article pulled free of the stack at an altitude of 10km, stabilise itself via integrated body flaps, then descend under parachutes for a hard-but-survivable landing in eastern Kazakhstan. The test was a success, despite the fact that two NK-35s failed on the Blok-A, leading to a loss of four out of the 24 first stage engines. The cause was later traced to a processing error during launch preparations, due in part to the punishing schedule of four N-1 launch campaigns within a year, and the confusion of concurrently processing N1F and N1-OK variants for Zvezda and Baikal missions. Ironically, this failure would probably have led to an abort had it occurred on a real launch, although the abort scenario in that case would have been to separate the entire Baikal orbiter after Blok-A depletion, followed by a glide back to Baikonur or a landing at the Ukrainka Air Base in the far eastern Amur Oblast.

With the campaign of orbiter atmospheric test flights completing in October 1985, preparations began to mate Baikal orbiter 1.01, the first flight model, to its N1-OK launcher for the first orbital test launch. Still scarred by the memory of the death of Komarov on Soyuz 1, Mishin agreed that the shuttle would launch without a crew for this first test, and in fact this would prove advantageous for other reasons. Without a crew on board, there was no need to complete installation of the complicated life support equipment that would otherwise be needed. Electrical power consumption would therefore also be greatly reduced, which when taken together with a planned single-orbit mission, meant that the heavy thermal control radiators would not be needed. This saved many months of work in preparing the orbiter, allowing Mishin to advance the test flight schedule.

Following two on-pad aborts, the first launch of the Baikal shuttle orbiter, designated mission 1K1, finally occurred on 8th December 1985. N1-OK vehicle 34L successfully placed orbiter 1.01 into a 251 x 255km orbit at an inclination of 51.6°. The spacecraft orbited the Earth twice, keeping its payload bay doors closed, before automatically firing its manoeuvring engines and decelerating back into the atmosphere. The re-entry was a little rougher than anticipated, but the thermal protection systems worked well enough, slowing the ship sufficiently to allow for deployment of the wings and jet engines. Here the first major anomaly occurred, as one of the twin jets failed to start. The shuttle’s autopilot quickly recognised the failure, and throttled down the remaining engine, using the aerodynamic surfaces of the V-tail to compensate for the yaw induced by the asymmetrical thrust. The orbiter was able to limp back to the runway at Baikonur, guided by radio beacons to an automatic touchdown.

As soon as the shuttle was safely back on Earth, TASS made a public announcement of this new Soviet space triumph to the world. The fully automatic nature of the mission was particularly highlighted as something of which the American Shuttle was incapable. With earlier test launches of the N1-OK rocket already having been publicly identified as “Baikal”, the press release for the first time gave a separate name to the first Soviet shuttle orbiter: Uragan (Hurricane). Following a further series of uncrewed test flights that would fully demonstrate the capabilities of the new spacecraft (the press release went on), crewed missions would soon begin, confirming the USSR’s position as the globe’s dominant space power.

In fact there was still considerable work to be done to get Uragan ready for a crew, and it was more than a year until a second shuttle mission was ready for lift-off on 20th February 1987. This second mission, designated 2K1, was also launched without a crew, but it would not remain unoccupied for long. Two days after Uragan had reached orbit, a Vulkan rocket lifted off from Baikonur carrying the Slava 26 mission, crewed by cosmonauts Aleksey Boroday, Eduard Stepanov and Valeri Polyakov.

View attachment 879714

After a two day orbital chase, Slava 26 made a close rendezvous with Uragan, and began a careful flyaround inspection of the orbiting spaceplane. Uragan appeared to be in good health, with the payload bay doors and newly-installed radiators fully deployed. Most importantly for the mission, the Airlock and Docking Module in Uragan’s payload bay had its APAS-85 docking port fully extended. Derived from the androgynous docking system developed for the Apollo-Soyuz mission, the APAS would allow Uragan to dock with any similarly equipped vehicle, be it a space station, Slava spaceship, or even a future Zvezda-derived lunar ferry. This would give greater flexibility in planning space operations, as well as allowing for rescue missions at short notice. It was this last scenario that Slava 26 was intended to simulate. With the recent example of Challenger fresh in everyone’s mind, Mishin wanted to make sure he had a method of retrieving shuttle crews from orbit should something go wrong.

Boroday guided Slava to a textbook docking with Uragan, and the three cosmonauts were soon able to board the shuttle, entering through the airlock to the aft Work Compartment (RO). Here they made a quick visual inspection of Slava through the RO’s upper and aft windows, before proceeding through the hatch separating the main body of the shuttle from the detachable nose section to enter the ship’s flight deck, the Command Compartment (KO). While Stepanov continued to the lower Habitation Compartment (BO), Boroday and Polyakov began activating Uragan’s manual controls.

View attachment 879715

Slava 26 spent three days docked with Uragan, during which time the crew gave the shuttle’s systems a thorough check-out. This included a (very careful) activation of the twin SBM robotic arms to perform an inspection of the exterior of the shuttle. Although not able to see all of Uragan’s exterior (special booms to allow full coverage were not yet completed), this didn’t prevent TASS from touting this as yet another improvement of the Soviet shuttle over its American equivalent. In fact NASA would soon have the same ability as part of their post-Challenger upgrades, but this didn’t stop TASS claiming another first for the USSR.

After undocking from Uragan, the crew of Slava 26 travelled on to the Zarya 3 space station, while the shuttle made an automated reentry and landing. This time both AL-31F engines started correctly, powering Uragan to a controlled touch-down seven days after launch.

The Baikal test programme of just a few years earlier had called for an additional 2K1 class rendezvous mission and at least two unpiloted docking missions to Zarya before a crew would be launched aboard the shuttle. However, by 1987 Mishin’s budgets were being severely squeezed. The response to Reagan’s “Battlestar America” programme was absorbing huge volumes of resources, with the military’s attention and patronage shifting away from the shuttle towards laser battlestations and orbital weapons platforms. Both Baikal and the lunar base programme were forced to compete for funding with both Glushko’s space station ambitions and with one another. In the face of this squeeze, and with the success of the first two shuttle missions, Mishin ordered a shortening of the Baikal test programme. The second shuttle orbiter, vehicle 1.02, provisionally named “Tsiklon” (Cyclone), would be ready for launch in just a few months. The next time a Soviet shuttle took to the skies, Mishin decreed, there would be a crew aboard.

We already know that Vulkan is an operational crewed rocket so Proton has been retired (I still wanted to see images and capabilities of the new launcher)

The only thing that worries me is that we won't see a successor to Zarya 3 (i.e. our Mir).

What happened with Challenger iTTL?With the recent example of Challenger fresh in everyone’s mind, Mishin wanted to make sure he had a method of retrieving shuttle crews from orbit should something go wrong.

Wait, did something happen with Challenger?

I remember the joints being discussed but tile inspection wasn't

just curious

What happened with Challenger iTTL?

did you get my message about the shuttle rename to Investigator instead of Bonaventure

just double checking

Love the update on the unusual Soviet shuttle, but I am also intrigued by the hints which our author is giving about what is happening both with other Soviet missions and the wider world in space exploration.

That sounds like Zvezda 9/10 is not only (mostly) successful, but it also had a foreign cosmonaut on board. Interkosmos on the moon, or something even more interesting?Together with the foreign policy coup of the Zvezda 10 lunar mission in February

With the recent example of Challenger fresh in everyone’s mind, Mishin wanted to make sure he had a method of retrieving shuttle crews from orbit should something go wrong.

So we know there was a major anomaly with Challenger, and it likely had something to do with loose tiles and an anomalous reentry, given the fact NASA was implementing measures to look at the tiles in space and the Soviets were concerned about retrieving shuttle from orbit.Although not able to see all of Uragan’s exterior (special booms to allow full coverage were not yet completed), this didn’t prevent TASS from touting this as yet another improvement of the Soviet shuttle over its American equivalent. In fact NASA would soon have the same ability as part of their post-Challenger upgrades

Reagan’s “Battlestar America” programme

...Battlestar America? Laser battlestations and orbital weapons platforms??? Seems like the equivalent of SDI in TTL is more... offensive in nature. Damn.patronage shifting away from the shuttle towards laser battlestations and orbital weapons platforms

I was reading about this, actually! As you might expect, it's kind of real, but mostly told in a way that is fake:There's this funny story how engineers preparing Sally Ride on her first flight (first american woman flight too) weren't sure about the number of tampons for her six day flight. They were even scared to ask their wifes, so then one chosen technician went to Sally and asked her something like: "Will hundred tampons be enough?"

I'm not completely sure if the story happened, but it illustrates how much was NASA gender biased. That leaves me with the same sexism in the soviet sector, if not a bit worse. According to another story, when Valentin Lebedev arrived at the Salyut 7 station, he gave Svetlana Savitskaya, second female cosmonaut, an apron with the words: "Get to work."

They're lightweight, you don't know how bad it can go, why not be really sure you look foolish for sending too many rather than risk astronaut health and have too few before you have data?Here’s the thing: Dr. Rhea Seddon, the only combination medical doctor, astronaut, and period-haver in the class of ’78, helped make the decision about how many tampons to include. According to a 2010 interview, the large number of tampons was a safety consideration. As she said, “There was concern about it. It was one of those unknowns. A lot of people predicted retrograde flow of menstrual blood, and it would get out in your abdomen, get peritonitis, and horrible things would happen.” According to Seddon, the women were skeptical of the concerns, and their preference was not to treat it as a problem unless it became a problem. But she was involved with the final decision made with the flight surgeons, and according to her:In other words, the story may have been less about idiot male techs and more about the NASA approach of solving all problems with more equipment. As Seddon remembers it, they decided to take the maximum amount they imagined a woman with a heavy period could need, multiplied that by two, and then added 50 percent more.We had to do worst case. Tampons or pads, how many would you use if you had a heavy flow, five days or seven days of flow. Because we didn’t know how it would be different up there. What’s the max that you could use? Most of the women said, “I would never, ever use that many.” “Yes, but somebody else might. You sure don’t want to be worried about do I have enough.”

Weinersmith, Kelly; Weinersmith, Zach. A City on Mars: Can we settle space, should we settle space, and have we really thought this through? (pp. 213-214). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Just a different pop-culture nickname for the same program, IIRC?...Battlestar America? Laser battlestations and orbital weapons platforms??? Seems like the equivalent of SDI in TTL is more... offensive in nature. Damn.

Possibly Galactica was more popular during its run so it wasn't cancelled due to its high cost, it might last to season 2 or 3 (if it was really popular)Just a different pop-culture nickname for the same program, IIRC?

That or Galactica 1980 was a smash hit

...Battlestar America? Laser battlestations and orbital weapons platforms??? Seems like the equivalent of SDI in TTL is more... offensive in nature. Damn.

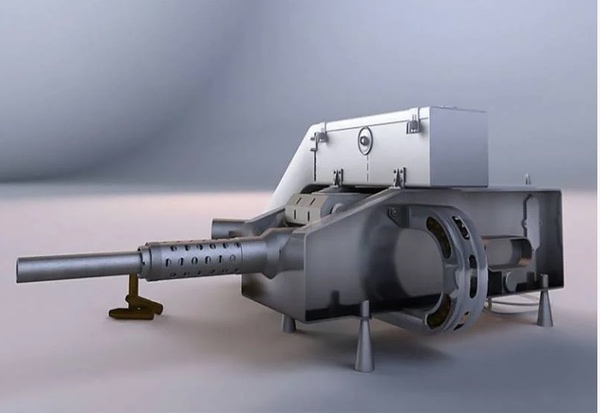

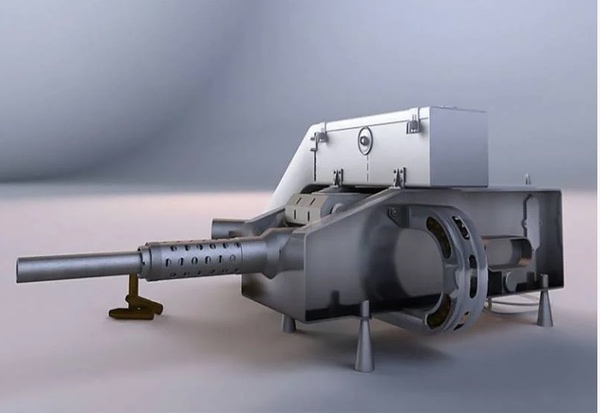

Funny you mention this, as The Space Review publishes another installment in their ongoing Bart Hendrickx/Dwayne Day series on US and Soviet military space stations. Which this week includes an image of that infamous Almaz NR-23 gun system:

Its a good way to prevent the American Imperialists from tampering with Superior Soviet technologyFunny you mention this, as The Space Review publishes another installment in their ongoing Bart Hendrickx/Dwayne Day series on US and Soviet military space stations. Which this week includes an image of that infamous Almaz NR-23 gun system:

Its a good way to prevent the American Imperialists from tampering with Superior Soviet technology

That's right. Eat lead, you Yankee running dog bastard.

The Russian Salyut 7 movie has that Russian theory that Challenger was launched to grab the station, even though it was launched way laterThat's right. Eat lead, you Yankee running dog bastard.

The Soviets and americans have a staredown in space

Wow! That Shuttle looks sort of funny on orbit with no wings. Intrigued by the little hints about the wider world. I'm still curious as to what Vulkan looks like here.

Last edited:

Share: