28 - The Raging 20s and New Ingredients in the Cauldron

The Raging 20s

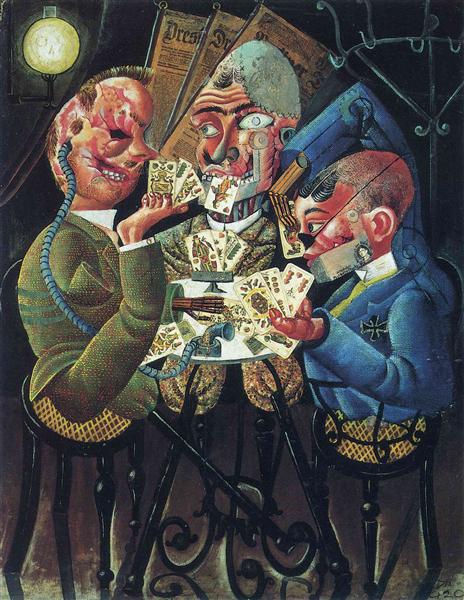

The Skat Players (1920) by Otto Dix, a dadaist painting showing the marks left by the Great War

The 20s are a tale of two continents: in the New World emerged from the Great War with modernized armed forces, economies suffering from the effects of full employment and societies that - while traumatized by the war - hummed with optimism and newfound wealth as the 1919 crunch gave way to the 1920 boom. Credit was cheap, cash was plentiful, culture thrived, and from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego prosperity followed peace.

But in the Old World, the 20s were an altogether more negative decade: the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman and Russian empires had created new borders between centuries-old communities, while the major belligerents that emerged from the war mostly intact territorially had nevertheless seen a generation die in the trenches and their economies buckle under the strain of total war and the crushing debt needed to sustain it for 4 years.

France, the UK and Italy ostensibly emerged from the war victorious, but as the ink dried on the treaties, an overwhelming feeling that the mass death of the Great War had been all for nothing. A generation’s worth of young men had died in the trenches, but the territorial adjustments that followed seemed paltry in comparison to the millions of casualties: France reclaimed Alsace and Lorraine, but its hopes of keeping the Saarland were dashed by plebiscite. Italy for its part secured South Tyrol, Trieste and some Dalmatian enclaves, but its dream of a mare nostrum on the Adriatic floundered against the rapidly consolidating Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Russia for its part could hardly count itself among the victors of WW1: excluded by the rest of the Entente from negotiations after their desperate pursuit of a separate peace a year before as revolution wracked the empire, it would see its borders shift sharply eastward as independence movements took hold from Finland to Ukraine and the Caucasus, and would spend much of the early 20s locked in a bitter civil war that sapped its strength and helped entrench its losses. The old imperial borders at Silesia or the Danube were nothing but a bitter memory by 1930, and nearly a dozen new countries now separated Moscow from its European ambitions. The revolutionary Soviet government survived its defeats, but at a terrible cost.

The emergence of so many new nations in central and eastern europe were a traumatic upheaval for the region: while the Western powers and the new Republican government of Germany would begin a glacial recovery in the latter half of the 1920s - and would even see a rapprochement between Paris and Berlin that brought down the latter’s burden of reparations substantially - the remnants of the Hapsburg and Romanov empires remained aflame with war for nearly a decade after the end of the Great War.

While the panslavic movement overtook the Austro-Hungarian’s Balkan territories - uniting under the crown of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia - and Romania expanded into Transylvania, the rest of the empire was still nominally controlled by the Hapsburg dynasty, and there was even a Hapsburg-appointed government that would sign the treaties that ended the war. But just as their authority had de facto been exercised by a hastily-assembled junta of German and Imperial military officers at war’s end (Germany having assumed control of the government as it intervened to prevent both the fall of Austria to Italian troops and the fall of the Empire with it), it became a government-in-exile soon after.

Events in Austria-Hungary took a dramatic turn after the sudden withdrawal of the German troops propping up the junta and its imperial facade: deeply unpopular both with the general public and its own junior officers and uniformed men, and there was much rejoicing when the gerontocratic junta was overthrown by a cadre of radicalized colonels, captains and cadets. There was considerably less rejoicing in the periphery of the empire however, and what followed the Decembrist Coup was a bloody, two year long civil war that pitted the revolutionary government in Vienna against Prague, Budapest and Bratislava and their nascent provisional governments.

The proclamation of the United Socialist Republics of the Danube, dubbed “Red Danube” by the press, would be a bigger shock to Europe than the proclamation of the Soviet Union: though reduced by a third, the Austro-Hungarian successor state secured its survival at the cost of land concessions to the Allies, Romania and Poland. Protected behind mountains on most fronts, the post-war upheaval gave the Red Danube the leeway to reshape the country and modernize it rapidly, especially as the USRD took in more and more radical exiles from its neighbors.

By the late 1920s, a semblance of peace - and it truly was a semblance, as tensions and claims criss-crossed the new borders that emerged from the Great War - returned to Central and Eastern Europe at last. The secret alliances of old were cast aside, and new ones were forged in the new order: Poland and Ukraine, born out of victory over the Bolsheviks and enlarged at expense of the Decembrists, would settle their border and announce their defense pact to much fanfare in Kyiv and Warsaw; the Baltic Republics bound themselves to one another in defense treaties aimed squarely at Moscow, while Finland fortified its border with the Soviets and sought allies to its West.

The sad truth is that the result of the war sparked by the powderkeg that was the Concert of Europe and the Armed Peace was that Europe splintered in a new way along national and ideological lines. The new borders that sprang up in Central and Eastern Europe may as well have been fuses; little did the leaders that rose to power in the violence of the early 20s know that - far from the dreams of a war to end all wars - that an even more violent outbreak of war was just around the corner.

New Ingredients in the Cauldron

While some authors may have been excused for thinking the world of globe-spanning empires and the corresponding fleets and armies to sustain them were the pinnacle of civilization, the outbreak of the Great War very quickly put that idea to rest. A general malaise and sense of disillusionment with the world order that both lead to the war and emerged - seemingly - unscathed, a feeling only exacerbated by the far quicker recovery of corporate profits before real wages.In short, the Great War had hollowed out a generation, left entire stretches of continental Europe reduced to smoldering ruins, burdened victors and vanquished alike with crippling debt and runaway deficits, making the lives of both living and future generations materially worse for no discernible gain for the immense majority of combatants. This sentiment varied of course - the new nations born from the ashes of the old empires certainly deemed their newfound independence historic triumphs - but the great powers that had all but sought it in pursuit of glory and ever greedier ambitions had emerged impoverished and weakened in every way.

The crisis this realization caused was all-encompassing: as early as the first year of the war, a pervasive sense that the whole conflagration was nothing but senseless slaughter sweeped the trenches. As the war dragged on, as shell-shocked survivors and battle-scarred “casualties” returned home and the true scale of the horror became apparent, the question of what it was all for burned in everyone’s mind.

That the response was dramatic polarization and radicalization is hardly a surprise: established parties rallied around the flag in the “trying times” of war, and parties sought out new ideas further afield instead. All stripes of left-wing and right-wing radicals found willing audiences in the troubled 20s, and all manner of conspiracy theories gained traction as people searched desperately to make sense of the world once more.

Radicalization on the right’s tended to be more hodge-podge; after all, many of the most strident nationalists that grew to prominence in the immediate aftermath of the Great War did so because they spoke of rejecting foreign influence and reverting the trends of the so-called first globalization. In this way, they tended to share enemies as opposed to goals, and while that shared enmity sometimes lead to sympathies between nationalist movements, they were tenuous at best (especially as many shared competing territorial claims).

On the left, however, there was at least a pretense of international coordination and solidarity, and many leftist parties even claimed a common socialist heritage. The reality, of course, was radically different: divergences decades in the making between more radical and more reformist wings eventually escalated into a clean break with the formation of a Third International in 1919, cleaving the world’s socialist movement in twain by 1920. The emergence of the Decembrists in Vienna was initially welcomed by Moscow, but by 1925, relations between Bolsheviks and Decembrists had cooled, and though there was no formal split in the International, the ramifications for the nascent Communist movement in the western democracies were more negative.

The consolidation of these dogmatically ideological regimes would have wide-reaching consequences in the following decades, but in the 1920s they seemed an obvious response to a crisis that shook the liberal consensus born of the twin revolutions (Industrial and French) to its very bedrock. It seemed to many at the time that the era of liberalism had passed, and ambitious new ideas that promised clean breaks with the past were especially appealing as a result.