In TTL’s 2024, I could see countries practicing eugenics in the manner you described as being one of the signs a country like that is a “rogue state” with a shitty human rights record.I do feel that eugenics as defined by "sterilising or removing unwanted gene carriers from the population" will die out except in the most extreme states

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

8mm to the Left: If Hitler Died in 1923

- Thread starter KaiserKatze

- Start date

18 - Bones of Iron, Veins of Steel

8mm to the Left: A World Without Hitler

“Hercule Poiroit wiped his mouth with the cloth serviette, carefully folding it up and replacing it atop his plate, concealing the burgundy Mitropa ‘M’. ‘We have eaten well, mon ami, and now we shall get down to brass tacks, as you English say, and find our murderer.’” - Excerpt from Agatha Christie's 1939 novel ‘The Kaiser's Ghost’, the mystery of a murdered German general and the rush to catch the culprit before he disappears forever.

Bones of Iron, Veins of Steel

“The new railway line will follow the pre-existing route along Rhine westward from Mainz, before breaking off at Bingen and cutting South through Bad Kreuznach and then West towards the Mosel,” Adenauer explained to the men to his left and right, tracing the path of the new train line on the map in front of them. “Idar and Oberstein are to be unified into a new municipality, Idar-Oberstein, which will serve as a junction linking the Trier-Kaiserslautern and Saarbrücken-Mainz lines.”

Nahetal Rail Line, 1935

(https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nahetalbahn)

The man to his right, newly-elected Minister-President of the Freistaat Rhinelands (Free State of the Rhineland) Peter Altmeier, examined the plans with appreciation. The formation of the new federal state had brought to light a number of problems with the administration in the region, a holdover from the old feudal system which had split the region between multiple different actors. The most egregious of these problems was that of infrastructure.

Up until the fall of the German Empire in 1918, the German railways had remained under the control of the constituent states and their respective rulers, which had frequently led to problems due to differing signals and systems. While the German Revolution had handed over control of this, and many other things, to the central government, the difficult domestic and financial situation had prevented the gaps from being filled. Now, though, with the economy flourishing, the time was ripe to to right that wrong.

“Are you fully convinced of Kaiserslautern as the provisional capital?” asked the man to Adenauer’s left, Wilhelm Weirauch, deputy director of the Deutsche Reichsbahn (German National Railway). “I understand the geographic appeal, but Ludwigshafen would be more practical from an infrastructural standpoint, not to mention possessing a far larger population.”

Adenauer shook his head. “Ludwigshafen sits on the border to Baden, and would be too easily overshadowed by Mannheim. Trier would have also been an acceptable option, but it remains under the Prussian boot.”

Squashed beneath the bulky Prussian Rhineland, the new Free State looked a sad little thing on the map. Absentmindedly, the Chancellor picked at the edges of it, wondering if it would ever be expanded to its rightful glory.

German Rhineland, 1935

(https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Weimar_Republic_states_map.svg)

“I agree, Kaiserslautern is the best option,” Minister-President Altmeier chimed in. “It is not the largest city, perhaps, but it at least bears a long history. Ludwigshafen was little more than a vanity project for the Bavarian king. Perhaps its new role will help Kaiserslautern flourish.”

Weirauch studied the map for a moment. “If we can regain Alsace, it would at least serve us well along a southern route towards Strasbourg,” he conceded, though it was clear that he was not fully convinced.

Adenauer did not care. It was not as though it would matter, anyway; the city was little more than a consolation prize, and the more unappealing it was as a capital, the easier it would be to dislodge and shift the focus to the true rhenish capital: Cologne. “The residents have been largely supportive of the new state,” he said, smoothly redirecting the focus of the conversation. “Voter turnout was high for the first election and the majority of the media is positive.”

“The most problematic area thus far has been Eupen-Malmedy, though this seems to be more based on lingering reintegration pains than any specific hatred for the new state,” Altmeier added as clarification. “The city of Malmedy, as I am sure you are aware, is Francophone, and there has been some violence against officials in the city and cries to rejoin Belgium, mostly by the younger generation. Belgium has refused to back their claims. In the worst case we can try and arrange limited autonomy in the region. I am sure that it will not pose a problem”

“See that it doesn’t, it would not due for such measures to undermine our credibility.” Adenauer was still not convinced of the wisdom of pushing for their Belgian claims, but what was done, was done.

“We are working to reintegrate the Vehnbahn back into our rail system; perhaps that will help stabilise the region,” Weirauch pointed out, gesturing to the former Belgian rail exclave which had now rejoined the Reich. “The Luxembourgers have already consented to us extending the line further south to their capital, as it opens the possibility of a faster route to Aachen and Maastricht.”

Luxembourg had been ripped from their customs union with Germany following the end of the Great War, and the new one which they had forged with Belgium was a pale reflection. The rebuilding of the railways and ties with Belgium was the first step; with German trains and products passing through their land, not to mention their own German-speaking nature, their future alignment with Berlin was only natural.

“Will the unions be a problem?”

“Difficult to say. There is a dangerously socialist slant to many of our workers, it is true, but they never fully recovered from the Depression, and with your government providing new jobs for the rails, I do not see a large opposition from the EdED or the DTV, at least if they want to prevent another exodus of their members.”

The EdED, short for Einheitsverband der Eisenbahner Deutschlands (United Union of German Railway Workers) was one of the most powerful and oldest unions in Germany, formed initially in 1897 before merging with other unions. Even with the economic downturn of the 1920’s they had remained a juggernaut, and when working alongside the other major union, Deutsche Transportarbeiter-Verband (German Transport Workers’ Union), or DTV, they had the power to put the squeeze on the government like none other.

“Let me deal with the unions,” Adenauer assured the duo. “There are always cracks, if one knows where to look. Pull on the right thread and the whole construction falls apart around you.”

One of the most iconic hallmarks of Germany throughout the last century has been their trains. As the largest country in Europe (overseas holdings exempted) in terms of both size and population, the German Reich is often referred to as the great train junction of Europe—it is almost impossible to cross the continent without setting foot on German soil, and more than 70% of all locomotives used in Europe were produced or at least designed in Germany. There are very few places across their nation which cannot be reached via the extensive network of high-speed and regional transportation, with even the popularity of aeroplanes and airships proving unable to dislodge the train from the hearts of Germans everywhere.

The 1930’s saw an explosion of rail usage across Germany, pioneered in large part by public works programs which largely favoured rail travel as an alternative to the less-accessible automobiles. When asked about their long-term goals for Germany, Minister for Transport Gottfried Treviranus said, “It is the goal of this government to connect Germans to Germany in a way never-before seen. By the end of the next decade, we want the whole of the Reich to be accessible to its citizens, no matter their origin, from the peak of the Zugspitze to the shores of Westerland and everything in-between. We will reinforce the Fatherland with bones of iron and veins of steel.”

Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus, 1936

(https://www.omnia.ie/index.php?navigation_function=3&europeana_query=Treviranus, Gottfried)

Treviranus would come to hold the post of Reich Minister for Transport for nearly twenty-two years, surviving multiple elections and governmental shifts; even the fall of the Republic wouldn't lessen his grasp on the ministry. This unmatched tenure is attributed to his single-minded pursuit of German technological supremacy and the lengths he took to ensure it.

In 1933, Germany had become home to the fastest train in the world, the Fliegender Hamburger (Hamburg Flyer), a diesel-electric locomotive running the route between the cities of Berlin and Hamburg at roughly 124 kilometres per hour. The train was a remarkable feat of engineering, but also a deeply exclusive one, with associated costs, such as the making of the locomotives themselves, forcing the Reichsbahn to limit its use to the aforementioned route.

Hamburg Flyer, 1933

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DRG_Class_SVT_137)

Treviranus had taken note of the train’s incredible feats and had petitioned for funds to extend the high-speed railway, but it was not until late 1935 that his requests bore fruit, courtesy of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.

In 1931, Germany had bid for and won the right to host the 1936 Olympic Games, a privilege which now von Lettow-Vorbeck’s government was obliged to fulfil. The president held little care for the event and as a result the work of planning it fell to Adenauer, a job he took to with relish, commissioning a new sports area and hand-picking individual venues. In his grand plan for the Olympic Games, a chance to demonstrate the peaceful and prosperous republic which had taken the place of (what he saw as) a decrepit monarchy, a high-speed rail connection between major German cities would be invaluable.

The majority of the Summer events had been planned to take place in Berlin, despite Adenauer’s personal distaste for the city, and the chancellor wanted to ensure the highest possible number of tourists would be able to reach the capital when the time came. With Treviranus’s help, he proposed to the Reichsbahn the idea of transforming the Hamburg Flyer route into a cross-German one, beginning in the city of Cologne and travelling via Hamburg to Berlin and then further on to Breslau with stops only in major cities. They were sceptical, but since the price largely came down to training and acquiring more trains, something that the central government agreed to subsidise, they acquiesced.

But Adenauer’s plans were larger than they had realised. Though the Summer Olympics were slated for Berlin, the Winter ones were going to take place in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, a town in Upper Bavaria. Thus, his proposal was followed by a second, more ambitious one: The creation of a brand new high-speed line from Berlin to Munich.

The difficulties in a new North-South route were greater than an East-West one, and came with associated risk. The South was more mountainous, which many felt made high-speed travel difficult if not impossible, and would bring in the complication which emerged from crossing from the Prussian train regions into the Bavarian ones. Conductors and engineers would need to be trained for the high-speed trains as well as for the regional differences, including signals from the days of the Königliche Bayerische Staats-Eisenbahnen (Royal Bavarian State Railways). Altogether, it was difficult to garner support outside of Trevinarus himself.

Adenauer would not be deterred, going so far as to enlist the help of Waggonbau Görlitz, the company behind the Hamburg Flyer, offering them tax breaks and government-sponsored investments in exchange for backing his proposal. The company saw the potential for profit in association with the Olympic Games, and agreed heartily. The fact that what he was doing was technically illegal made no difference to Adenauer; he had his eyes on a goal, and so went after it with the full force of his influence and power.

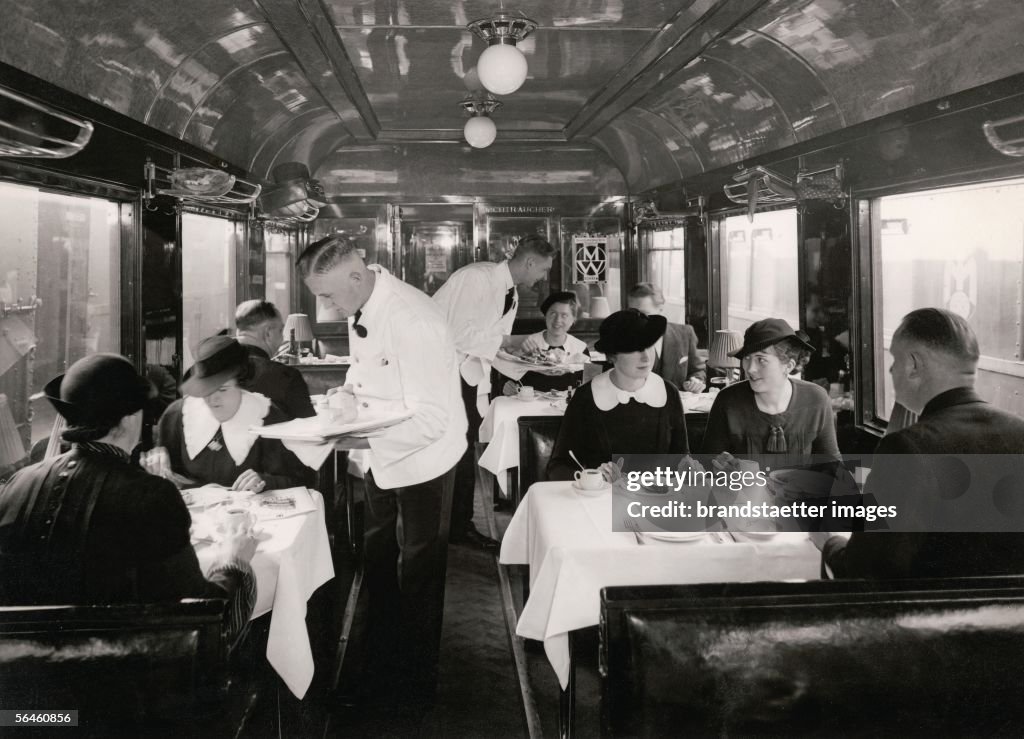

Another potential backer for the project was Mitropa, Germany’s premier company when it came to managing dining and sleeper cars. Founded in 1916 as a wartime competitor to the far more famous Belgian CIWL (Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits), Mitropa, short for “Mitteleuropa” (Central Europe), held a monopoly on the aforementioned services across Germany. After the war’s end, many of their routes through Eastern Europe and the Balkans had been stolen by said competitor, and they sought to restore glory to their name. A North-South rail line across Germany would be ripe for profit, not to mention continued hopes of German expansion carrying their influence throughout Europe as had been during the Great War.

Mitropa Dining Car circa 1935

(https://www.gettyimages.in/detail/n...ography-around-1935-blick-news-photo/56460856)

Adenauer’s hard work succeeded, and the Brandenburg-Bavaria rail line would be officially opened for public use in September, 1936. To say that Minister Treviranus was ecstatic would be an understatement, and he poured his heart and soul into advertising it to the wider European world, beginning an ongoing tradition of integration between the Ministry for Transport and the tourist industry, eventually culminating in its expansion into the Reich Ministry for Transport and Tourism several years later.

For all the economic hopefulness brought about by the Olympics, they likewise placed focus on the remaining weakness of the Reichsbahn and of Germany as a whole: Its poor relations with the nations bordering it. With Germany surrounded on three sides by nations of cool, if not outright hostile disposition, not to mention the Reich’s own claims and hunger for growth, it was wondered by many if the era of peace would last, or if perhaps the competitiveness of these Olympics games were merely a prelude to a far greater and more deadly form of competition.

Outside the window of the cosy First Class carriage in which Martha von Lettow-Vorbeck and her three youngest children were sitting, the scenery of the green Pomaranian coast rushed by, a blur of trees and lakes with the occasional glimpse of the vast Baltic Sea beyond. Her two youngest, Heloise and little Ursula (though not so little now, all of nine years old) had fallen asleep shortly after Köslin, while Arnd remained engaged in the book he'd brought with him. It was a shame that their eldest sibling, Rüdiger, hadn't been able to join them on their brief holiday, but at the age of fifteen he was growing more invested in his studies and had less interest in spending a weekend touring museums and old castles in Königsberg with his family.

The train gave a little jump and the carriage shook. Heloise stirred and Martha was quick to reach over and pet her head until she drifted back off to sleep. Glancing over, she saw that Arnd had abandoned his text in favour of watching the scenery zip past, and was glad that at least three of her children would be able to have this experience.

Taking the children to see the old historic sites of Prussia had been a shared desire of hers and Paul's, and though his work as German President would not let him leave for even a single weekend, he had been quick to ensure that the rest of his family would enjoy utmost comfort while travelling. A five-star hotel awaited them in the city and a chauffeur had been hired to pick them up from the station and ferry them to all of their desired destinations. They had a whole list of plans—the former royal castle in the city centre, the Teutonic fortress in Marienburg, the Masurian Lakes, and of course the Free City of Danzig. Martha only wished that they could've come by air, as Arnd had begged, but Paul remained sceptical of the safety and so rail it was. For their own security, an entire First Class carriage had been sealed off, the only occupants being the von Lettow-Vorbecks in the foremost compartment and two bodyguards in the next one over.

A soft knock came at the door and it was opened to reveal the conductor, a kind-faced older man with a silver moustache which matched the silver buttons on his jacket. On his breast was pinned the black-and-gold logo of the Reichsbahn. “I apologise for disturbing you,” he said, keeping his voice down, “but we are nearing the Polish Corridor and I have to begin my preparations for the Polish border check and our conversion into a Korridorzug.”

Arnd piped up from his seat by the window, asking, “Korridorzug? Is our train changing?”

The conductor, evidently a parent or otherwise accustomed to children himself, took a moment to explain it to the curious boy. The special diplomatic status accorded to Danzig and the Polish Corridor had left Germany divided by foreign territory, a situation made especially difficult for the movement of trains via the former Preußische Ostbahn (Prussian Eastern Railway) connecting Berlin to Königsberg, the same route on which they now travelled. A solution had thus been devised which would not require German citizens to acquire a Polish visa for what amounted to less than a half-hour of their time within Polish (and Danziger) territory: Becoming a Korridorzug (sealed diplomatic train).

At the station of Lauenberg, the final major stop within German territory, Polish border agents had been authorised to seal the doors of all passenger carriages from the outside, thereby preventing anyone from embarking or disembarking between Lauenberg and the first station within East Prussia, Marienburg.(Any visitors intent on visiting Danzig would be forced to disembark and re-enter the city from the East, in order to have their passports properly checked by border control.) By doing so, they could limit the chance of unwanted incursions into their sovereign territory, while likewise abiding by the rights of fair transport demanded by the Entente for German citizens. This was not without problems, as the conductor began to enunciate, before pausing and glancing at Martha, asking for her permission to continue. Knowing to what he would refer, and aware that her son would not be fazed by it, she nodded.

“In 1925, there was a train derailment due to poor track maintenance,” he explained to the fascinated boy. “Many people died in the crash, and the ones who did not were trapped in the carriage for several hours before help arrived.”

“The tracks were built by Germans, but it was the job of the Poles to maintain them,” Martha added, drawing her son’s attention. “They didn’t, and our people paid the price.”

“That’s terrible!”

“Hush,” she reprimanded him softly, placing a finger upon her lips to remind him of his sleeping sisters. “It is,” she added. “This ‘solution’ is merely a cause for greater strife and suffering.” She turned to the conductor. “Must we do anything to prepare?”

“No, ma’am,” he said with a shake of his head. “However, the Polish guards will perform a walk-through of the train before sealing it, and I wanted you to be prepared. I do not expect them to try anything with you, but there have been… incidents in the past. Luggage destroyed, passengers harassed, things in that vein.”

Martha nodded in understanding. “Thank you for taking the time to let us know.”

The conductor closed the door and moved on, undoubtedly to pass the same message on to the other travellers.

“Mother,” her son began, “if things are so bad, why does Father not do anything to stop it? He is the most powerful man in Germany, isn’t he? Can’t he make the Poles give us back our land?”

“It isn’t that simple, I’m afraid. His power has limits, especially outside of Germany. Poland wants to hold this territory just as badly as we want it back, and that could mean war.”

“But why is that bad? We would win!”

“That is what we believed before the Great War,” she reminded him. “It cost us a great deal when we were proven wrong.”

“We only lost ‘cause we were stabbed in the back, though.”

“And that is why war is a risk. Perhaps, facing off against Poland alone, we would win, but what would happen if France attacked from the other side? Or if the British once again try to starve our children with their navy? We would assuredly lose, and not only would we never see Danzig again, we could lose more German homelands, and become too weak to ever regain them.”

Arnd clearly had not considered that notion, and so lapsed into silence. Several minutes passed until the train began to shudder, the application of the brakes bringing it to a slow halt at Lauenberg main station. Through the window several passengers could be seen disembarking, and simultaneously several men in brown uniforms with the red-and-white armband of Polish police discussing briefly with the conductor before boarding the train. As the First Class carriage sat at the front of the train, it was through there that they passed first, coming to a stop in front of the doors leading into the Lettow-Vorbeck’s compartment. At some point the two guards assigned to their protection had appeared to stand beside the door, and while they allowed the Poles to enter, they kept a close eye while doing so.

The majority of the group continued onward to investigate the other passengers, with one remaining to examine their compartment. The guard was young, younger than Martha had expected, certainly no older than twenty at most. His blond hair was cropped short to his head and his dark blue eyes cast over them suspiciously, brows drawn. His eyes lingered on their limited baggage and Arnd in particular, who was giving the man his own hostile stare.

“Where are you going?” the Pole demanded in accented but otherwise perfect German.

“Who do you think—” began Arnd hotly before Martha cut him off.

“Königsberg, for a weekend visit,” she interjected smoothly, shooting her son a look which warned him not to open his mouth again. “Would you like to see our papers?” She held them out.

The guard snatched them with one quick motion and began to peruse them. Technically, legally, he did not have the right to examine her documents any more than he had the right to check luggage, but the legalities often fell subsidiary to other matters. After several long seconds he tossed them onto the seat beside her, giving a curt nod, closing the door, and stomping off.

The door had scarcely closed then Arnd was yelling, “How dare he treat you like that! I am going to tell Father and he will make sure this sort of thing never happens again!”

“You will do no such thing,” Martha snapped, turning her sternest gaze on him. “Your father will never hear a word of this.”

He was at first cowed, before frustration elicited a further, “But why?”

She sighed, and then again when she saw how his eruption had woken his sisters. “What good would that achieve? I am unhurt, my pride is undamaged, and our journey will continue soon.”

“But he insulted you!”

“Do you think your mother so brittle and timid that such nonsense would affect me?”

“Well… no, but–”

“You inherited your father’s spirit,” Martha said, more gently this time, “but you must also understand that there is a time to fight, and a time to accept things as they are.”

Arnd frowned. “Like what you said about war. It is a risk.”

“Exactly. I am not saying that fighting against injustice is bad, merely that it must be done strategically. Triggering a crisis over a rude border guard is simply not worth the risk.”

“But then what is worth the risk? How do we know we won’t just be waiting forever for our chance and it never comes?”

“We cannot know. We can only hope, and wait, and plan, so that if the day does come where we can turn the tables on our enemy, we will be ready.”

I will be updating the maps at some point with a regional map of the new Free State of the Rhineland which includes the cities, as well as both new train lines for the first map, but haven't had time as of late.

Something tells me that guard just went on her "list" much like Private Pike went on that U-boat captains one in a nearby reality...

Which one is that?Something tells me that guard just went on her "list" much like Private Pike went on that U-boat captains one in a nearby reality...

private pike is from ' Dad's Army'Which one is that?

Don’t tell ‘er, Mislosz!Something tells me that guard just went on her "list" much like Private Pike went on that U-boat captains one in a nearby reality...

Dad’s Army.Which one is that?

Sorry me being a bit British there.Which one is that?

Werner von Bloomberg's book is named "War in the East".

Does that tacitly imply, that there will not be a war in Western Europe in this universe?🤔

Also did Blomberg live longer there? Cause the book is dated 1947. He died not even living up to see conclusion of Nuremberg Trials, in early 1946. If so, how? He died from a lung cancer as far as I know. It's unlikely that Hitler getting shot will butterfly this. You can't even argue that being a commanding officer in WW2 and induced stress did that to him, as Blomberg was sacked in 1938 and spent WW2 retired.

Does that tacitly imply, that there will not be a war in Western Europe in this universe?🤔

Also did Blomberg live longer there? Cause the book is dated 1947. He died not even living up to see conclusion of Nuremberg Trials, in early 1946. If so, how? He died from a lung cancer as far as I know. It's unlikely that Hitler getting shot will butterfly this. You can't even argue that being a commanding officer in WW2 and induced stress did that to him, as Blomberg was sacked in 1938 and spent WW2 retired.

Last edited:

Once again, terrific stuff. Very keen to see where this goes!

I'm most interested in how a full Rhenish state would actually work, internally and within Germany. But on top of that, I'm always keen to read about what other countries are up to!

I'm most interested in how a full Rhenish state would actually work, internally and within Germany. But on top of that, I'm always keen to read about what other countries are up to!

How so? A book solely about the Normandy campaign doesn't imply the nonexistence of everything else in the war.Werner von Bloomberg's book is named "War in the East".

Does that tacitly imply, that there will not be a war in Western Europe in this universe?🤔

War in the East sounds like something of epic scale, something like exactly entire War, not just one of the fronts of War. Otherwise it could have been named different way. "Campaign in Russia", "Campaign in the East", "Eastern Front", or something else along those lines.How so? A book solely about the Normandy campaign doesn't imply the nonexistence of everything else in the war.

I am grasping at straws, I know, and it's very subjective, but I think that this excerpt confirms that there is not going to be a widescale and protracted fighting in Western Europe at the very least, if not any armed hostilities at all.

Well, the work could have been published posthumously and/or he died shortly after finishing the work.Also did Blomberg live longer there? Cause the book is dated 1947. He died not even living up to see conclusion of Nuremberg Trials, in early 1946. If so, how? He died from a lung cancer as far as I know. It's unlikely that Hitler getting shot will butterfly this. You can't even argue that being a commanding officer in WW2 and induced stress did that to him, as Blomberg was sacked in 1938 and spent WW2 retired.

Werner von Bloomberg's book is named "War in the East".

Does that tacitly imply, that there will not be a war in Western Europe in this universe?🤔

Especially as nasty things are likely to happen vis-a-vis both France and Italy in the future and it is implied some horrible things went down in Yugoslavia ITTL.How so? A book solely about the Normandy campaign doesn't imply the nonexistence of everything else in the war.

To quote Wikipedia: "Blomberg's health declined rapidly while he was in detention at Nuremberg. He faced the contempt of his former colleagues and the intention of his young wife to abandon him. It is possible that he manifested symptoms of cancer as early as 1939. On 12 October 1945, he noted in his diary that he weighed slightly over 72 kilograms (159 lb). He was diagnosed with colorectal cancer on 20 February 1946. Resigned to his fate and gripped by depression, he spent the final weeks of his life refusing to eat."Also did Blomberg live longer there? Cause the book is dated 1947. He died not even living up to see conclusion of Nuremberg Trials, in early 1946. If so, how? He died from a lung cancer as far as I know. It's unlikely that Hitler getting shot will butterfly this. You can't even argue that being a commanding officer in WW2 and induced stress did that to him, as Blomberg was sacked in 1938 and spent WW2 retired.

Firstly, I feel that the lack of WW2 is enough to Change a lot of smaller Things, even stuff Like Smoking Rates (which tend to be much higher in soldiers). On top of that, his imprisonment seems to have taken the biggest toll on him--he would have died soon, but I could see him making it till 1948 or 49 with good care. In this case, I envisioned him finishing the book on his deathbed. The original version will be somewhat of a cult book, since the military strategy will be useful but it will be riddled with racist analogies, and is generally only cited in phrases or paragraphs in other, more neutral works.

Once again, terrific stuff. Very keen to see where this goes!

I'm most interested in how a full Rhenish state would actually work, internally and within Germany. But on top of that, I'm always keen to read about what other countries are up to!

So is Adenauer, but currently all he gets is a rump state which is more Bavarian than Rhenish--at least right now

Or the author could just write "War in the East" and "War in the West" because that rolls off the tongue better. Titles prove nothing at the moment.... Otherwise it could have been named different way. "Campaign in Russia", "Campaign in the East", "Eastern Front", or something else along those lines.

Okay, I give up. We will see where this TL takes us anyway.Or the author could just write "War in the East" and "War in the West" because that rolls off the tongue better. Titles prove nothing at the moment.

Understood, thanks for explanation!Firstly, I feel that the lack of WW2 is enough to Change a lot of smaller Things, even stuff Like Smoking Rates (which tend to be much higher in soldiers). On top of that, his imprisonment seems to have taken the biggest toll on him--he would have died soon, but I could see him making it till 1948 or 49 with good care. In this case, I envisioned him finishing the book on his deathbed. The original version will be somewhat of a cult book, since the military strategy will be useful but it will be riddled with racist analogies, and is generally only cited in phrases or paragraphs in other, more neutral works

Also I love when people theorise, so please keep it up!Understood, thanks for explanation!

There is a hint in there for you, too, with the fact that his book contains "racist analogies". Not a big hint, given the time, but still!

Oberstein

Bruh, proto-ICEThe majority of the Summer events had been planned to take place in Berlin, despite Adenauer’s personal distaste for the city, and the chancellor wanted to ensure the highest possible number of tourists would be able to reach the capital when the time came. With Treviranus’s help, he proposed to the Reichsbahn the idea of transforming the Hamburg Flyer route into a cross-German one, beginning in the city of Cologne and travelling via Hamburg to Berlin and then further on to Breslau with stops only in major cities. They were sceptical, but since the price largely came down to training and acquiring more trains, something that the central government agreed to subsidise, they acquiesced.

Share: