You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Lands of Red and Gold, Act II

- Thread starter Jared

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 71 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Lands of Red and Gold #122: A Man Of Vision Lands of Red and Gold #123: What Becomes Of Dominion Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #5.5: Interview With The Eʃquire Lands of Red and Gold is now published! Aururian Fire Management Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #15: Into Darkness Contest - Guess The Character Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #16: Minutes Take HoursSo, BEENY is the only puzzle left?

Apparently, although Beeny has been known to post in the LoRaG thread a bit.

Very clever. I got a few of them, but not too many.

I think I made many of them more obscure than they were meant to be, but either way it was fun to write.

Lands of Red and Gold #98: When Cider Over-Ferments

Lands of Red and Gold #98: When Cider Over-Ferments

“Useless – nothing but a land of ice and mice.”

- Bangalla, Nuttana explorer, during his first (and only) visit to Penguin Island [Macquarie Island] [1]

* * *

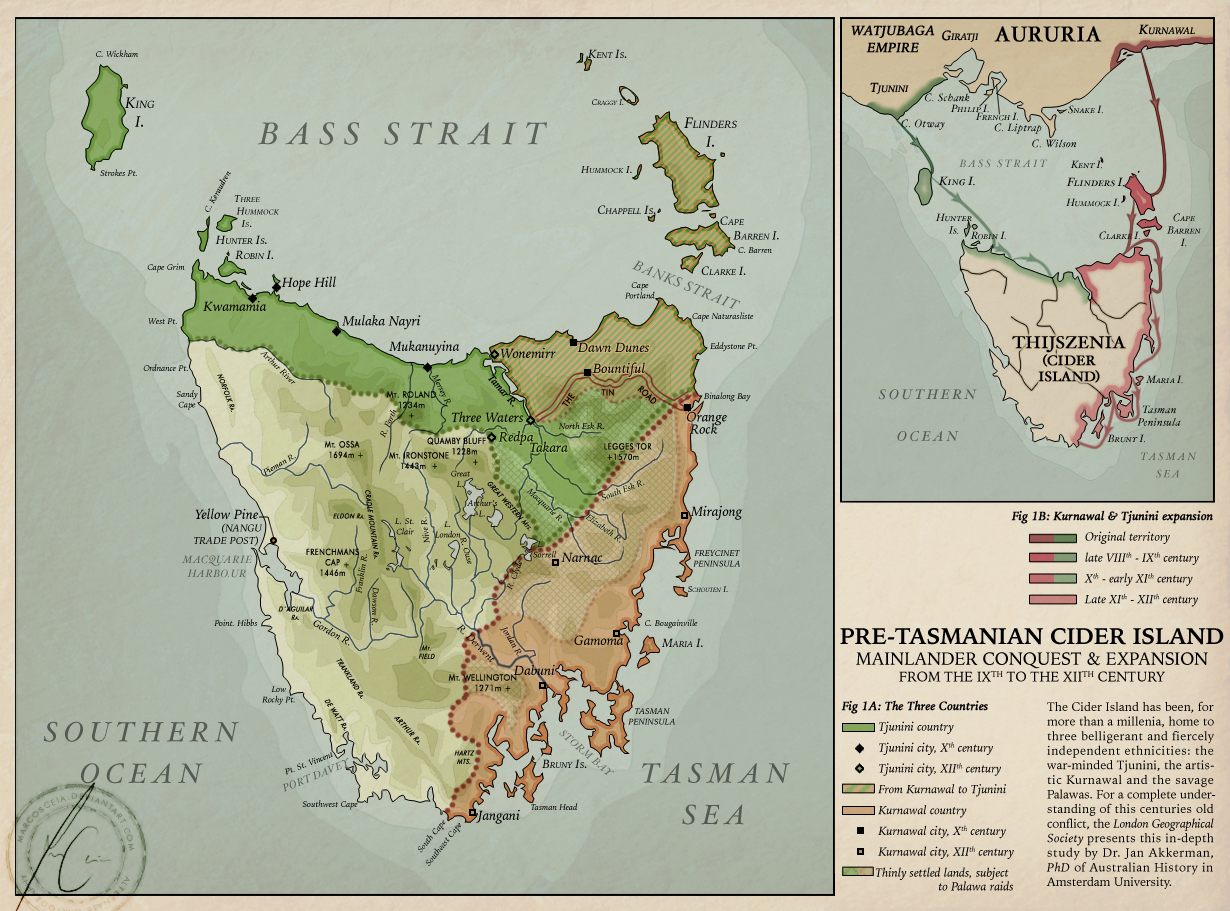

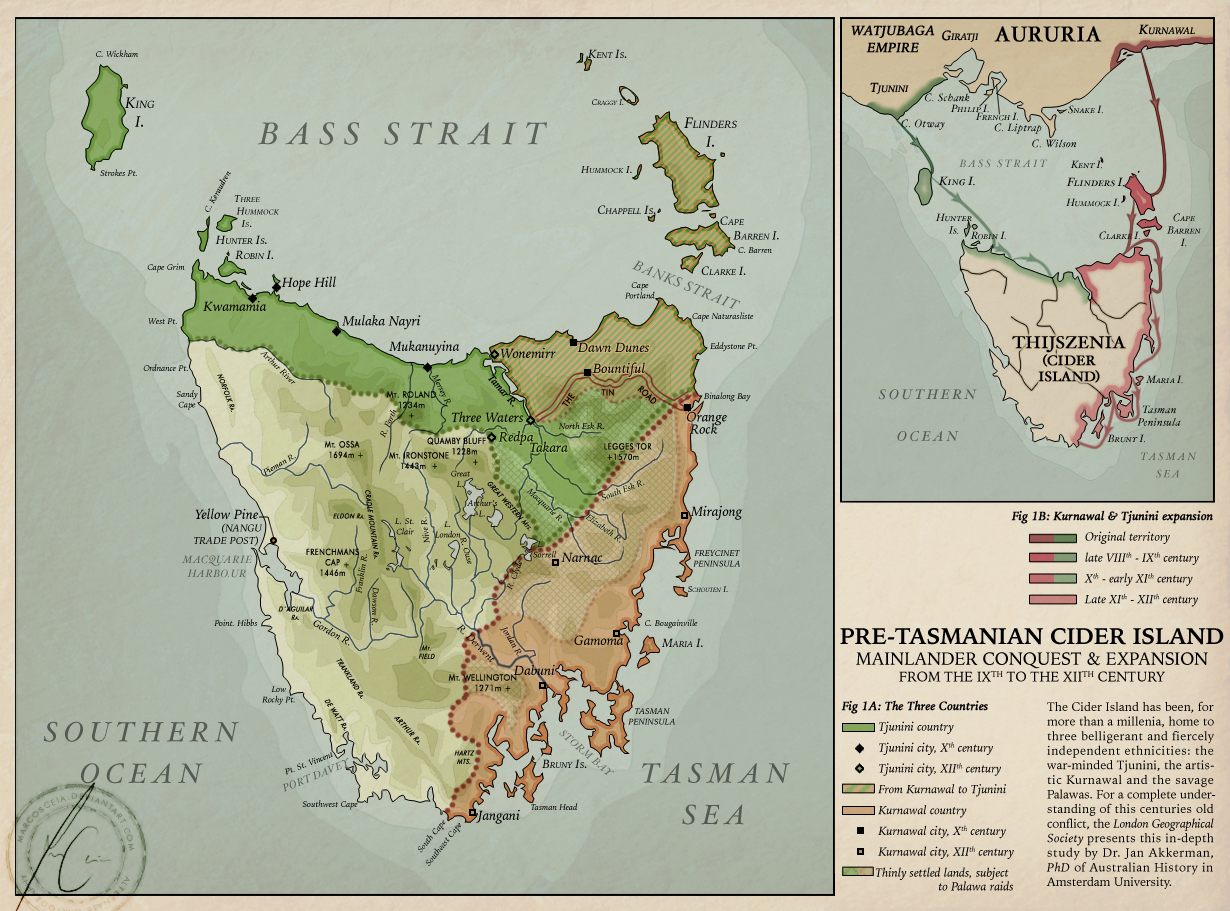

Tjul Najima, it was once called. The island of bronze, in the Nangu tongue. The richest source of tin known to the ancient Aururian peoples, with a supply so abundant that Tjul Najima’s inhabitants continued to use bronze despite contact with iron-using peoples.

Tjul Duranj, it became known. The island of (gum) cider, in the Nangu tongue. The exclusive source of the eponymous beverage, made from the fermented sweet sap of the cider gum. An island where valiant Tjunini battled with crafty Kurnawal, while the wild Palawa roamed the hills and raided where they wished.

New Holland, or so it became christened by François Thijssen, commander of the first European (Dutch) expedition to visit the island. An island whose peoples had no proper appreciation of the most valuable commodity their island produced: gold.

* * *

* * *

The Cider Isle had once been connected to the mainland of Aururia, until it was cut off by the rising oceans. For nearly ten millennia, the hunter-gatherer Palawa occupied the island without any contact with other humans. Isolation ended in the early ninth century AD, when two groups of Gunnagalic-speaking farmers began migrations to the island. These became the Tjunini and the Kurnawal.

The Tjunini and Kurnawal fought a long series of wars, beginning with the War of the Princess sometime during AD 1060-1080. This process led the Tjunini to establish themselves along the northern coast of the Cider Isle, while the Kurnawal occupied the east coast. The Palawa had some intermingling with the newcomers, particularly the Tjunini, but in time were pushed into the interior of the island.

The Tjunini were usually politically divided into small kingdoms, and periodically united under the rule of a high king, the so-called Nine-Fold King. The Kurnawal formed a mostly unitary state, with occasional breakaway cities. The two peoples fought numerous wars over the centuries, a process which continued even after Thijssen’s voyage. The Palawa had taken up a hunter-gardener lifestyle in the interior, and regularly raided into the lands of both of the more agricultural peoples.

At the time of European contact, the Cider Isle still supplied duranj and gold to the larger states of the mainland, while tin and bronze were exported to the Māori of Aotearoa, and to some east coast peoples. In addition to imported mainland domesticates, they also farmed a local species of goose, a grazing bird [2] whose manure helped to fertilise their fields better than the practices of most mainland peoples. The fertility of Cider Isle agriculture was noted on the mainland, although popular belief there was that the Cider Isle soils were richer because they were regularly fertilised with blood because the three peoples fought each other so often.

Wars were indeed common between Cider Isle peoples. That had been traditional for centuries. The first contact with Europeans did nothing to change that practice. War broke out again between Tjunini and Kurnawal in 1629-1637, ending due to blister-rash [chickenpox] and with a result that favoured the Tjunini. Further waves of Old World diseases did not do much to prevent new wars; the Cannon War (1645-1648) resulted in a strong Kurnawal victory, while the War of the Ear in 1657-1658 ended in bloody stalemate.

It seemed that nothing could break the Tjunini and Kurnawal hatred and their endless cycle of wars. Until, at last, something inconceivable happened: the Tjunini and Kurnawal found a common foe.

* * *

The stormy, treacherous, often-shallow waters of what the local inhabitants call the Narrow Sea [Bass Strait]. Ten thousand years ago most of the Narrow Sea was dry land, a shallow plain with abundant wildlife and verdant vegetation, in the cooler, wetter climes of the last Ice Age. The rising seas had swallowed those former plains, for the most part, though they left plenty of small islands and semi-submerged rocks to form shipping hazards in later times.

The highest parts of those former plains remained above the waves, forming habitable islands. The largest islands were Benowee [King Island] in the western end of the Narrow Sea, and a cluster of islands near the eastern end, the largest of which was Tavaritja [Flinders Island] and the second-largest was Truwana [Cape Barren Island] [3]. These islands held refugee populations for millennia, until the vagaries of changing climate, and inbreeding among small populations, meant that those peoples died out.

The Narrow Sea islands were then uninhabited until they became stepping stones for the migrating Tjunini and Kurnawal on their first voyages to the Cider Isle. While the main groups of migrants moved further south, small but viable populations remained behind. Benowee had always been settled by the Tjunini, while Tavaritja and its neighbouring islands were eventually conquered by the Tjunini, who thus ruled all inhabited Narrow Sea islands at the time of European contact.

In one of allohistory's reversals, this time those Narrow Sea islands would be used to attack the Tjunini and Kurnawal who had once used them to attack the Cider Isle.

* * *

6 January 1671

Bountiful, Tjul Duranj / Cider Isle [Scottsdale, Tasmania]

Symbolism mattered. Narawntapu, King of the Kurnawal, Sovereign of the Great Island, knew that to be true in most circumstances, but nowhere was it more meaningful than here. Narawntapu stood outside the walls of Bountiful, the most ancient capital of the Kurnawal. The accurséd Tjunini had ruled it for so long, until the great triumphs of the Cannon War let the Kurnawal regain it, avenging the ancient defeat [4]. Now, when a bargain needed to be struck, what better reminder to the Tjunini than this incontestable testament to Kurnawal prowess?

Narawntapu stood surrounded by ten hand-picked, valiant warriors, each of whom had personally killed at least one man in the last war. The number of warriors was on of the many terms which had been carefully negotiated before this meeting. The Tjunini scouts could check the terrain as much as they wanted, with any number of scouts, but only ten warriors on either side could remain when the kings drew near. The location was within sight of Bountiful’s walls, naturally – Narawntapu would not pass up such an opportunity – but carefully out of bowshot or musket fire. Narawntapu had guaranteed safe-conduct, and even meant to honour it, but apparently the Nine-Fold King possessed little trust in such assurances.

Of course, given the previous wars, he may have some grounds for mistrust. A salient reminder, that, of the problems that needed to be overcome this day. Too much could be lost, if today’s negotiations failed.

Soon enough, the Tjunini monarch arrived. Wurangkili, son of Dharug, King of Dawn Dunes and Nine-Fold King, cut an impressive figure. Tall and broad-shouldered, as far as could be seen beneath the cloak that was wrapped around him and hung low to cover most of his legs. A cloak dyed royal green [5], but trimmed around the edges with genuine thread-of-gold. That cloak would be extremely heavy, and surely took strong shoulders to wear comfortably. Doubtless it was a special commission from the Yadji; the weavers of gold were unrivalled in their craft.

Apart from his green and gold cloak, Wurangkili’s most notable feature was a beard which would make an Atjuntja jealous, with black-and-grey hair stretching far down his chest. Looped gold earrings, bracelets and nose-stud marked the ornamentation of a man who demanded loyalty from many subject kings.

In contrast, Narawntapu wore little adornment. His trousers and yamadi [6] were of undyed grey. He had no neck-rings, ear-rings, bracelets or other jewellery. The only mark of his royalty was the brass mace – its hilt surrounded by three bands of gold – that he carried in his left hand [7]. Narawntapu had always mistrusted the Tjunini love of ostentation. Any proper Kurnawal knew better than to adopt adornment for its own sake; wit was always more important, and no amount of decoration could make up for a lack of cunning.

When the Tjunini king drew near, Narawntapu waved for most of his warriors to step back, save for his most trusted bodyguard who remained standing on his left side. Likewise, only one bodyguard accompanied Wurangkili as he made the last few steps. The words to be said today were for kings alone, not for common warriors.

Wurangkili inclined his head in what was not quite a bow.

Narawntapu returned the gesture, as equally as he could. He did not bother to proclaim any greetings or welcome to Bountiful; that would have made his message rather too blunt. The Nine-Fold King understood now about the strength of Kurnawal arms. What mattered was finding common purpose for both Tjunini courage and Kurnawal craftiness.

“Did you ever think you would see a day such as this?” Narawntapu asked. “A day when Tjunini and Kurnawal might consider standing together against a common foe?”

“I never thought I would see a day where I would need to answer the question can I trust a Kurnawal?” Wurangkili said. “Until now, that question never needed answering, because the reply was always no.”

“Never was a Kurnawal born who lacked craftiness,” Narawntapu said. “Yet for all of your declarations of honour, never did a man rise to become Nine-Fold King without understanding the dance of politics, either.”

“True enough,” the Tjunini monarch said, acknowledging with a shake of his head. “But what concerns me more now is how we manage the dance of war.”

“The isles of the Narrow Sea have fallen,” the Kurnawal king said. “Now they are havens to allow the Pakanga to raid where they will. This harms both of our peoples, yes, but yours suffer more for it.”

“What do you offer, then?”

“It is not what I offer, but what I suggest would help both of us,” Narawntapu said. “First, an acknowledgement of peace, proper peace, between us.”

“You truly think we can have an endless peace?”

“Death and war are the only two certainties in life, as the poets say.” He shrugged. “Our differences will not be forgotten, of course. We have hated each other for so long, I doubt we will ever have a permanent peace. But we must put our hatred to one side, for now. Time enough to resume our conflicts when the Pakanga have been driven off.”

And if the endless plagues do not swallow us all, Narawntapu mentally added, but that was a fear for another day.

“And second?”

“Second, where we can do so, working together to repulse any Pakanga conquests on the Great Island. No matter where they occur, they must be pushed back. Bad enough that these Māori renegades hold the lesser isles. If they establish themselves properly on the Great Island, then we will have great difficulty in ever driving them out.”

“That much trust could be shown, perhaps.”

Narawntapu was briefly surprised at the quick semi-agreement, until he realised that the Nine-Fold King had had much time to consider the situation he faced. The other king’s home city of Dawn Dunes [Bridport] was doubly exposed to danger. The city was not too far to the north of here, after all, and had the Pakanga threatening by sea and a potential Kurnawal advance by land. Wurangkili must have been at least considering the notion even before Narawntapu had first requested this parley. It took no genius to realise the danger that the Pakanga posed.

Just the latest danger. Every plague has been worse than the one before. The Great Death took so much from us. So much of what we built has been brought to ruin.

“Do you propose that any peace we make should include the Palawa?”

“The Palawa have suffered even more from the plagues than your people or mine.”

Narawntapu did not bother to add that some of his subjects had chosen to flee inland from their former coastal homes. Away from Pakanga raids, into former Palawa lands, where they could farm more securely. They feared the Pakanga much more than the reduced threat of Palawa retaliation. There would be more land to occupy, later, if the Pakanga could be driven back, and if the plagues did not swallow all potential settlers. Perhaps Tjunini had made similar migrations in their own land, but if not, Narawntapu did not want to give them ideas. The Pakanga were the great threat for now, but he still would not trust the Tjunini any more than he had to.

“Few the Palawa may be, but they could still be a dagger in our backs, if they see us weaken our inland garrisons to fight Māori.”

The Kurnawal king shook his head. “It is something to consider for later, but not yet, I think. The Palawa do not even have any king to negotiate peace with; it would be an endless discourse among their surviving clans. For now, I think, we must talk about how we will make peace.”

“Yes, I think we should,” Wurangkili said, with the hint of a smile on his face.

* * *

The Māori had spent centuries waging war against their bitter enemies the Māori, but the Harmony Wars still marked a great change in Aotearoa, with the introduction of new weaponry and the consolidation of political power [8]. A great many warriors were displaced during this warfare, and many of them opted to become Pakanga and raid overseas. As a major trading partner and fabled source of wealth, the Cider Isle was naturally a prime target for these raids.

The first small-scale Pakanga raids on the Cider Isle began in the early 1650s. These were groups of raiders driven by desire for wealth and glory, and they mostly struck coastal targets, killing people they found, stealing what they liked, and sometimes carrying off slaves. Pakanga who came to the Cider Isle during this period were looking to regain their mana by valiant deeds, which would let them reclaim a place in Aotearoa; they did not seek to conquer lands or settle permanently.

This gradually changed during the following decades, as the combination of increasing numbers of Pakanga and greater political consolidation in their home islands meant that for many displaced warriors, returning was not possible no matter how much mana they earned. So Pakanga aims began to move more toward conquest and permanent settlement.

The Māori were extremely familiar with the geography of the Cider Isle and its surroundings, since they had been trading there for centuries. So they quickly identified the most vulnerable targets for conquest: the Narrow Sea islands. Tavaritja [Flinders Island] and Truwana [Cape Barren Island] were invaded and occupied by Pakanga raiders in 1667. They were briefly liberated by Tjunini soldiers the following year, but then recaptured by a fresh wave of Pakanga. Benowee [King Island] fell in 1669, completing the Māori conquest of the Narrow Sea.

In themselves, the Narrow Sea islands could not sustain large populations. They were too small, the soils mostly infertile, and they held limited permanent water. However, as bases for raiding parties, or even for wars of conquests, they were ideal. Seizing these islands let the Pakanga stage ever more attacks on both sides of the Narrow Sea, but most of all on the Cider Isle. The threat was obvious and ever-growing, and serious enough that the Tjunini and Kurnawal agreed, for the time being, to put aside their ancient hostility.

The 1670s were the time of the greatest Pakanga assault, when attacks seemed an almost weekly occurrence, and the numbers of Pakanga raiders seemed endless. At one time or another during this decade, they attacked more or less every coastal town on the Big Island. Pakanga raiders even struck at the surviving Nangu colony of Yellow Pine [Strahan] inside its difficult harbour, though so many Pakanga ships were wrecked during that raid that they never tried to return [9].

The most vigorous conquest attempts were directed at the closest ports to the Narrow Sea islands, and in one case, the most vulnerable port. The Tjunini cities of Dawn Dunes [Bridport], Wukalina [Tomahawk] and Kwamania [Smithton], and the Kurnawal cities of Larapuna [Ansons Bay] and Orange Rock [St Helens] were repeatedly targeted, because of their proximity to the Narrow Sea islands.

Joint efforts by Tjunini and Kurnawal repulsed the first attack on Dawn Dunes in 1671, but this attack would be followed by many others. Wukalina fell in 1672, the first mainland city to be occupied; close to Truwana, and with difficult hills separating it from other cities, it was easier for the Pakanga to occupy than for others to defend. The same fate befell the small Kurnawal city of Larapuna in 1673. In the same year, the isolated Kurnawal city of Jangani [Cockle Creek] fell. This was a strongly-fortified city held by a renegade group of Kurnawal who did not acknowledge their king. It had proven impossible for the Kurnawal monarchs to re-establish control, over several decades, but the Pakanga conquered it by stealth, as they so often did.

The Pakanga assaults grew ever stronger throughout most the decade. Beleaguered, often attacked, and difficult to reinforce, Dawn Dunes eventually fell in 1675. Some other coastal Tjunini cities were captured for varying periods – Kwamania fell twice – but were recaptured in time. For the Kurnawal, Orange Rock was occupied for several months in 1674, and again for a few months over 1675-1676, although they eventually recaptured it on both occasions. While some cities could be reconquered easily, Dawn Dunes, Wukalina and Larapuna proved impossible to reconquer for a long time, since they were too easily reinforced by Pakanga.

The plagues, the many scourges of the Time of the Great Dying, continued even during the worst of the Pakanga raids. Bloat-throat [diphtheria] burned through the Cider Isle between 1673-1674, followed by an outbreak of death-cough [pertussis / whooping cough] in 1676-7. In what they did not realise was a stroke of great fortune, the relative handful of people who later died from scar-blister [smallpox, Variola minor] in 1682-3 were far fewer than those who would have been killed had the Cider Isle’s first outbreak been the deadlier variant [Variola major] of the disease.

Between the plagues and the seemingly-endless Pakanga raids, the Tjunini and Kurnawal found themselves severely short of manpower. By 1676, their position looked dire. The northeast of the island was firmly under Pakanga rule – Orange Rock had not yet been reconquered – and every month seemed to bring more Pakanga across the Gray Sea [Tasman Sea]. In desperation, Kings Wurangkili and Narawntapu turned to new sources of manpower: the Pakanga themselves.

The Pakanga were not a united group, being divided both by old inter-iwi hatreds and more recent religious wars between Catholic, Plirite and traditionalists. The occupiers of the Narrow Sea islands were traditionalists, and most of the Pakanga who raided the Cider Isle were of the same faith, together with smaller numbers of Catholics. The Tjunini and Kurnawal monarchs chose to recruit Pakanga of their own, preferably Plirite, to aid them in their struggles against the would-be conquerors [10].

Some of these recruitment efforts involved promises of land grants for the new Pakanga. This marked the true level of desperation amongst the Cider Isle’s peoples, for they traditionally viewed their land as sacred and not to be given to any other people but their own. Under this pressure, however, the Kurnawal offered land grants around Orange Rock to Pakanga mercenaries, so that they could recapture the city and then defend it afterward. The Tjunini offered similar land grants around their most hard-pressed cities of Kwamania and Hope Hill [Stanley], in exchange for defending against other raiders. In other cases, Pakanga were recruited simply as mercenaries, lured both by pay and by careful choice of iwi that were rivals to those now threatening the Cider Isle. At various times, the Dutch, British and Nuttana all assisted in transporting Pakanga to aid the Cider Isle’s defenders.

With some Māori also acting as defenders, the Pakanga raids into the Cider Isle were much less successful. The Pakanga did occupy some cities at times, but they did not make any further ongoing conquests. While raids continued into the 1680s, the actual Pakanga settlements were limited to the north-eastern corner of the Big Island, together with distant and resilient Jangani in the south. During this time, the Harmony Wars were gradually ending in Aotearoa, which cut off the supply of fresh Pakanga raiders.

By 1685, it appeared that the external Pakanga threat was finally over. Launching a full reconquest of the new Māori regions, however, would prove to be more difficult. With the foreign menace receding, neither Tjunini nor Kurnawal properly trusted the other to cooperate in expelling the interlopers, fearing betrayal. The Kurnawal did succeed in expelling the Pakanga from Jangani in 1687, with some of the defenders betraying their comrades in exchange for land grants, and the rest of the defenders sold as slaves to the Nuttana.

In 1688-9 the Tjunini and Kurnawal finally launched a joint reconquest of Dawn Dunes. When the city fell, King Wurangkili proclaimed that the city had to be restored to him as his ancient birthright. King Narawntapu responded by negotiating vassalage for the remaining Pakanga in Wukalina and Larapuna; recognising that since those towns had been flooded by Pakanga driven out from Dawn Dunes, reconquering the region was a practical impossibility anyway. The Kurnawal monarch had himself declared the ariki iwi of the Māori in the north-east, and recognised the rule of the ariki hapū beneath him.

With these events, the immediate dangers had gone, but the peoples of the Cider Isle had been gravely weakened by plague and warfare, and vulnerable to further pressure from abroad.

* * *

In the wider world, the 1660s and 1670s (and early 1680s) were marked by the Anglo- Dutch Wars, struggles that were fought principally in Europe but with conflicts that touched much of the globe. These struggles gave the indigenous peoples of the Third World some respite from the colonial pressure that had applied in previous decades.

By the end of the Anglo-Dutch Wars, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) and East India Company (EIC) had tacitly agreed to partition much of the Orient into spheres of influence, where they would not interfere with each other. The East Indies went to the VOC, while India and the whole subcontinent (except for a Dutch presence in parts of cinnamon-rich Ceylon) became the preserve of the EIC. Each company allowed the other a free hand in their allotted regions. The previous four decades of official and unofficial warfare had led the Lords Seventeen and Court of Directors each to judge that partition and steady if not overwhelming profits was better than squandering endless resources fighting each other.

In those allocated regions, the VOC and EIC focused their attention on curtailing the influence of the other colonial powers which had emerged (or re-emerged) while the Dutch and English were locked in the massive struggles of the Anglo-Dutch Wars: the French, the Portuguese, the Danes, and the Swedes. Where not combating those colonial rivals directly, they sought to re-establish their influence and trading connections with the local powers.

No such partition agreement applied in Aururia. Aururia had become the most valuable prize in the Oriental struggles of the two great trading companies. Gold, silver, kunduri, jeeree, and an abundance of novel spices ensured this competition. The best of those spices, sweet peppers and lemon verbena [lemon myrtle], were so valuable that they could even be traded to elsewhere in the Orient for greater profits; from the European perspective, much better than having to supply bullion from Europe. In such an environment, the Dutch and English made every effort to fight each other and gain control of the resources of the Third World.

This struggle played out in the Cider Isle as much as anywhere in the Third World. With the Anglo-Dutch Wars over and the Pakanga threat subsiding, the VOC and EIC resumed their struggle for influence in the Cider Isle, with the Compagnie d’Orient (CDO) [French East India Company] running interference. These companies’ determination grew ever greater with the weakening population; so many of the existing peoples of Aururia were declining with the Great Death and the plagues that followed during the Time of the Great Dying.

For while the population of the Third World was collapsing, the companies’ desire for trade goods was ever-expanding, particularly in sweet peppers which were required in ever-greater numbers to sustain their trade in the Orient and burgeoning European demand. The pre-contact Third World would have been capable of supplying any conceivable volume of European trade demand, but the ravages of plague and war had reduced most of that population, leading to huge foreign pressure on those who were left to supply this and other spices.

The Cider Isle had an excellent climate for growing the common varieties of sweet peppers; here the crops required little if any irrigation, unlike most of the accessible mainland areas [11]. As such, the VOC and EIC wanted to take as much control as needed to ensure that the survivors re-oriented their economy into production of spices, together with gold mining. The much-reduced population of the Cider Isle could not withstand this foreign influence. No formal protectorate may have been declared, but by 1690 the Kurnawal kingdom was an EIC client state in all but name. Likewise, the VOC sent enough arms and mercenaries to the Nine-Fold King that he became not only their effective vassal, but so that he could also break the old Tjunini political structure. Before, the Nine-Fold King had simply been the most prominent ruler but with vassal kings; under King Wurangkili and (after 1692) his son, the Nine-Fold King became the genuine ruler of all the Tjunini.

In such an environment, the old gum cider production almost, but not quite, vanished. The native peoples might still refer to their land as the Cider Isle, but this was not matched by their actual production, where it would have been more accurate to rename their homeland as the Pepper Isle. In such an environment, with European companies promoting production and mercenaries on hand where needed, the Tjunini and Kurnawal also sought to curtail destructive Palawa raids, and to expand their control into fresh fertile soils beyond their coastal territories. The few remaining Palawa retreated into the rugged terrain of the interior, where digging them out was more trouble than it was worth, unless the Palawa provoked retaliation through raids. (They mostly didn’t.)

As for the Tjunini and Kurnawal, despite their weakened population, despite further infighting risking direct European control, they did not stop fighting each other. Hostilities resumed in 1694-6, in what would be called the Unmaking War. This ended in a Kurnawal victory, allowing them to recapture Dawn Dunes. Of course, given the many wars between the two peoples, the odds were that the Tjunini would recapture the city soon enough.

* * *

[1] The mice that Bangalla refers to were in fact kiore, Polynesian rats, deposited there by previous Māori visitors to Penguin Island.

[2] That is, the Cape Barren goose (Cereopsis novaehollandiae), a grazing bird which is a useful source of both meat and eggs.

[3] The names for both Tayaritja (Flinders Island) and Truwana (Cape Barren Island) were in fact borrowed from the names which the Palawa gave to those islands. The Palawa still knew of those islands, even though they did not inhabit them.

[4] i.e. the War of the Princess, a struggle immortalised in song, and which possibly holds an elemental of historical truth. See post #13.

[5] This comes from a process using native indigo (Indigofera australis), a relative of true indigo (I. tinctoria). The Aururian species of indigo produces a similar blue-purple dye to true indigo, but with further treatment fibres that have already been dyed blue can be modified to a brighter green shade. To the Tjunini, this is the most valuable colour, royal green.

[6] A yamadi is a kind of collarless, V-neck shirt that is a common dress item amongst urban Kurnawal (and some Tjunini), but which is much plainer that would traditionally be worn by nobility, let alone royalty.

[7] The Kurnawal royal mace is not the only potential regalia they use, since the king also wears a plain gold coronet in formal settings. Having a mace made of brass is a sign of considerable wealth, since unlike their common bronze, brass must be imported, ultimately from the Tjibarri desert mines of Silver Hill [Broken Hill, NSW].

[8] See posts #94 and #95.

[9] Yellow Pine [Strahan] lies inside a large but shallow harbour that the Nangu call Timber Haven and which historically was called Macquarie Harbour. As could be guessed from the name, the Nangu use it as one of their main sources of timber for shipbuilding. The entrance to Timber Haven is extremely dangerous for visiting ships, since it is a narrow, shallow channel with dangerous currents, and whose depth often shifts depending on the deposits of sediment from the rivers that flow into the harbour. In this Pakanga raid, many ships were lost trying to get into and out of the harbour.

[10] The Tjunini and Kurnawal are themselves largely Plirite, having been converted by Nangu priests, although they retain some syncretic beliefs. This common religion has never stopped them from fighting each other.

[11] Sweet peppers (Tasmannia spp) are naturally alpine or cool temperate crops which require very high natural rainfall. Being further south, the Cider Isle is usually cool enough to sustain these crops even in coastal areas. The alpine areas of the mainland are equally capable of growing sweet peppers without needing irrigation, but these are far enough inland (and have poor roads) that transporting the crops to ports is much more difficult.

* * *

Thoughts?

“Useless – nothing but a land of ice and mice.”

- Bangalla, Nuttana explorer, during his first (and only) visit to Penguin Island [Macquarie Island] [1]

* * *

Tjul Najima, it was once called. The island of bronze, in the Nangu tongue. The richest source of tin known to the ancient Aururian peoples, with a supply so abundant that Tjul Najima’s inhabitants continued to use bronze despite contact with iron-using peoples.

Tjul Duranj, it became known. The island of (gum) cider, in the Nangu tongue. The exclusive source of the eponymous beverage, made from the fermented sweet sap of the cider gum. An island where valiant Tjunini battled with crafty Kurnawal, while the wild Palawa roamed the hills and raided where they wished.

New Holland, or so it became christened by François Thijssen, commander of the first European (Dutch) expedition to visit the island. An island whose peoples had no proper appreciation of the most valuable commodity their island produced: gold.

* * *

* * *

The Cider Isle had once been connected to the mainland of Aururia, until it was cut off by the rising oceans. For nearly ten millennia, the hunter-gatherer Palawa occupied the island without any contact with other humans. Isolation ended in the early ninth century AD, when two groups of Gunnagalic-speaking farmers began migrations to the island. These became the Tjunini and the Kurnawal.

The Tjunini and Kurnawal fought a long series of wars, beginning with the War of the Princess sometime during AD 1060-1080. This process led the Tjunini to establish themselves along the northern coast of the Cider Isle, while the Kurnawal occupied the east coast. The Palawa had some intermingling with the newcomers, particularly the Tjunini, but in time were pushed into the interior of the island.

The Tjunini were usually politically divided into small kingdoms, and periodically united under the rule of a high king, the so-called Nine-Fold King. The Kurnawal formed a mostly unitary state, with occasional breakaway cities. The two peoples fought numerous wars over the centuries, a process which continued even after Thijssen’s voyage. The Palawa had taken up a hunter-gardener lifestyle in the interior, and regularly raided into the lands of both of the more agricultural peoples.

At the time of European contact, the Cider Isle still supplied duranj and gold to the larger states of the mainland, while tin and bronze were exported to the Māori of Aotearoa, and to some east coast peoples. In addition to imported mainland domesticates, they also farmed a local species of goose, a grazing bird [2] whose manure helped to fertilise their fields better than the practices of most mainland peoples. The fertility of Cider Isle agriculture was noted on the mainland, although popular belief there was that the Cider Isle soils were richer because they were regularly fertilised with blood because the three peoples fought each other so often.

Wars were indeed common between Cider Isle peoples. That had been traditional for centuries. The first contact with Europeans did nothing to change that practice. War broke out again between Tjunini and Kurnawal in 1629-1637, ending due to blister-rash [chickenpox] and with a result that favoured the Tjunini. Further waves of Old World diseases did not do much to prevent new wars; the Cannon War (1645-1648) resulted in a strong Kurnawal victory, while the War of the Ear in 1657-1658 ended in bloody stalemate.

It seemed that nothing could break the Tjunini and Kurnawal hatred and their endless cycle of wars. Until, at last, something inconceivable happened: the Tjunini and Kurnawal found a common foe.

* * *

The stormy, treacherous, often-shallow waters of what the local inhabitants call the Narrow Sea [Bass Strait]. Ten thousand years ago most of the Narrow Sea was dry land, a shallow plain with abundant wildlife and verdant vegetation, in the cooler, wetter climes of the last Ice Age. The rising seas had swallowed those former plains, for the most part, though they left plenty of small islands and semi-submerged rocks to form shipping hazards in later times.

The highest parts of those former plains remained above the waves, forming habitable islands. The largest islands were Benowee [King Island] in the western end of the Narrow Sea, and a cluster of islands near the eastern end, the largest of which was Tavaritja [Flinders Island] and the second-largest was Truwana [Cape Barren Island] [3]. These islands held refugee populations for millennia, until the vagaries of changing climate, and inbreeding among small populations, meant that those peoples died out.

The Narrow Sea islands were then uninhabited until they became stepping stones for the migrating Tjunini and Kurnawal on their first voyages to the Cider Isle. While the main groups of migrants moved further south, small but viable populations remained behind. Benowee had always been settled by the Tjunini, while Tavaritja and its neighbouring islands were eventually conquered by the Tjunini, who thus ruled all inhabited Narrow Sea islands at the time of European contact.

In one of allohistory's reversals, this time those Narrow Sea islands would be used to attack the Tjunini and Kurnawal who had once used them to attack the Cider Isle.

* * *

6 January 1671

Bountiful, Tjul Duranj / Cider Isle [Scottsdale, Tasmania]

Symbolism mattered. Narawntapu, King of the Kurnawal, Sovereign of the Great Island, knew that to be true in most circumstances, but nowhere was it more meaningful than here. Narawntapu stood outside the walls of Bountiful, the most ancient capital of the Kurnawal. The accurséd Tjunini had ruled it for so long, until the great triumphs of the Cannon War let the Kurnawal regain it, avenging the ancient defeat [4]. Now, when a bargain needed to be struck, what better reminder to the Tjunini than this incontestable testament to Kurnawal prowess?

Narawntapu stood surrounded by ten hand-picked, valiant warriors, each of whom had personally killed at least one man in the last war. The number of warriors was on of the many terms which had been carefully negotiated before this meeting. The Tjunini scouts could check the terrain as much as they wanted, with any number of scouts, but only ten warriors on either side could remain when the kings drew near. The location was within sight of Bountiful’s walls, naturally – Narawntapu would not pass up such an opportunity – but carefully out of bowshot or musket fire. Narawntapu had guaranteed safe-conduct, and even meant to honour it, but apparently the Nine-Fold King possessed little trust in such assurances.

Of course, given the previous wars, he may have some grounds for mistrust. A salient reminder, that, of the problems that needed to be overcome this day. Too much could be lost, if today’s negotiations failed.

Soon enough, the Tjunini monarch arrived. Wurangkili, son of Dharug, King of Dawn Dunes and Nine-Fold King, cut an impressive figure. Tall and broad-shouldered, as far as could be seen beneath the cloak that was wrapped around him and hung low to cover most of his legs. A cloak dyed royal green [5], but trimmed around the edges with genuine thread-of-gold. That cloak would be extremely heavy, and surely took strong shoulders to wear comfortably. Doubtless it was a special commission from the Yadji; the weavers of gold were unrivalled in their craft.

Apart from his green and gold cloak, Wurangkili’s most notable feature was a beard which would make an Atjuntja jealous, with black-and-grey hair stretching far down his chest. Looped gold earrings, bracelets and nose-stud marked the ornamentation of a man who demanded loyalty from many subject kings.

In contrast, Narawntapu wore little adornment. His trousers and yamadi [6] were of undyed grey. He had no neck-rings, ear-rings, bracelets or other jewellery. The only mark of his royalty was the brass mace – its hilt surrounded by three bands of gold – that he carried in his left hand [7]. Narawntapu had always mistrusted the Tjunini love of ostentation. Any proper Kurnawal knew better than to adopt adornment for its own sake; wit was always more important, and no amount of decoration could make up for a lack of cunning.

When the Tjunini king drew near, Narawntapu waved for most of his warriors to step back, save for his most trusted bodyguard who remained standing on his left side. Likewise, only one bodyguard accompanied Wurangkili as he made the last few steps. The words to be said today were for kings alone, not for common warriors.

Wurangkili inclined his head in what was not quite a bow.

Narawntapu returned the gesture, as equally as he could. He did not bother to proclaim any greetings or welcome to Bountiful; that would have made his message rather too blunt. The Nine-Fold King understood now about the strength of Kurnawal arms. What mattered was finding common purpose for both Tjunini courage and Kurnawal craftiness.

“Did you ever think you would see a day such as this?” Narawntapu asked. “A day when Tjunini and Kurnawal might consider standing together against a common foe?”

“I never thought I would see a day where I would need to answer the question can I trust a Kurnawal?” Wurangkili said. “Until now, that question never needed answering, because the reply was always no.”

“Never was a Kurnawal born who lacked craftiness,” Narawntapu said. “Yet for all of your declarations of honour, never did a man rise to become Nine-Fold King without understanding the dance of politics, either.”

“True enough,” the Tjunini monarch said, acknowledging with a shake of his head. “But what concerns me more now is how we manage the dance of war.”

“The isles of the Narrow Sea have fallen,” the Kurnawal king said. “Now they are havens to allow the Pakanga to raid where they will. This harms both of our peoples, yes, but yours suffer more for it.”

“What do you offer, then?”

“It is not what I offer, but what I suggest would help both of us,” Narawntapu said. “First, an acknowledgement of peace, proper peace, between us.”

“You truly think we can have an endless peace?”

“Death and war are the only two certainties in life, as the poets say.” He shrugged. “Our differences will not be forgotten, of course. We have hated each other for so long, I doubt we will ever have a permanent peace. But we must put our hatred to one side, for now. Time enough to resume our conflicts when the Pakanga have been driven off.”

And if the endless plagues do not swallow us all, Narawntapu mentally added, but that was a fear for another day.

“And second?”

“Second, where we can do so, working together to repulse any Pakanga conquests on the Great Island. No matter where they occur, they must be pushed back. Bad enough that these Māori renegades hold the lesser isles. If they establish themselves properly on the Great Island, then we will have great difficulty in ever driving them out.”

“That much trust could be shown, perhaps.”

Narawntapu was briefly surprised at the quick semi-agreement, until he realised that the Nine-Fold King had had much time to consider the situation he faced. The other king’s home city of Dawn Dunes [Bridport] was doubly exposed to danger. The city was not too far to the north of here, after all, and had the Pakanga threatening by sea and a potential Kurnawal advance by land. Wurangkili must have been at least considering the notion even before Narawntapu had first requested this parley. It took no genius to realise the danger that the Pakanga posed.

Just the latest danger. Every plague has been worse than the one before. The Great Death took so much from us. So much of what we built has been brought to ruin.

“Do you propose that any peace we make should include the Palawa?”

“The Palawa have suffered even more from the plagues than your people or mine.”

Narawntapu did not bother to add that some of his subjects had chosen to flee inland from their former coastal homes. Away from Pakanga raids, into former Palawa lands, where they could farm more securely. They feared the Pakanga much more than the reduced threat of Palawa retaliation. There would be more land to occupy, later, if the Pakanga could be driven back, and if the plagues did not swallow all potential settlers. Perhaps Tjunini had made similar migrations in their own land, but if not, Narawntapu did not want to give them ideas. The Pakanga were the great threat for now, but he still would not trust the Tjunini any more than he had to.

“Few the Palawa may be, but they could still be a dagger in our backs, if they see us weaken our inland garrisons to fight Māori.”

The Kurnawal king shook his head. “It is something to consider for later, but not yet, I think. The Palawa do not even have any king to negotiate peace with; it would be an endless discourse among their surviving clans. For now, I think, we must talk about how we will make peace.”

“Yes, I think we should,” Wurangkili said, with the hint of a smile on his face.

* * *

The Māori had spent centuries waging war against their bitter enemies the Māori, but the Harmony Wars still marked a great change in Aotearoa, with the introduction of new weaponry and the consolidation of political power [8]. A great many warriors were displaced during this warfare, and many of them opted to become Pakanga and raid overseas. As a major trading partner and fabled source of wealth, the Cider Isle was naturally a prime target for these raids.

The first small-scale Pakanga raids on the Cider Isle began in the early 1650s. These were groups of raiders driven by desire for wealth and glory, and they mostly struck coastal targets, killing people they found, stealing what they liked, and sometimes carrying off slaves. Pakanga who came to the Cider Isle during this period were looking to regain their mana by valiant deeds, which would let them reclaim a place in Aotearoa; they did not seek to conquer lands or settle permanently.

This gradually changed during the following decades, as the combination of increasing numbers of Pakanga and greater political consolidation in their home islands meant that for many displaced warriors, returning was not possible no matter how much mana they earned. So Pakanga aims began to move more toward conquest and permanent settlement.

The Māori were extremely familiar with the geography of the Cider Isle and its surroundings, since they had been trading there for centuries. So they quickly identified the most vulnerable targets for conquest: the Narrow Sea islands. Tavaritja [Flinders Island] and Truwana [Cape Barren Island] were invaded and occupied by Pakanga raiders in 1667. They were briefly liberated by Tjunini soldiers the following year, but then recaptured by a fresh wave of Pakanga. Benowee [King Island] fell in 1669, completing the Māori conquest of the Narrow Sea.

In themselves, the Narrow Sea islands could not sustain large populations. They were too small, the soils mostly infertile, and they held limited permanent water. However, as bases for raiding parties, or even for wars of conquests, they were ideal. Seizing these islands let the Pakanga stage ever more attacks on both sides of the Narrow Sea, but most of all on the Cider Isle. The threat was obvious and ever-growing, and serious enough that the Tjunini and Kurnawal agreed, for the time being, to put aside their ancient hostility.

The 1670s were the time of the greatest Pakanga assault, when attacks seemed an almost weekly occurrence, and the numbers of Pakanga raiders seemed endless. At one time or another during this decade, they attacked more or less every coastal town on the Big Island. Pakanga raiders even struck at the surviving Nangu colony of Yellow Pine [Strahan] inside its difficult harbour, though so many Pakanga ships were wrecked during that raid that they never tried to return [9].

The most vigorous conquest attempts were directed at the closest ports to the Narrow Sea islands, and in one case, the most vulnerable port. The Tjunini cities of Dawn Dunes [Bridport], Wukalina [Tomahawk] and Kwamania [Smithton], and the Kurnawal cities of Larapuna [Ansons Bay] and Orange Rock [St Helens] were repeatedly targeted, because of their proximity to the Narrow Sea islands.

Joint efforts by Tjunini and Kurnawal repulsed the first attack on Dawn Dunes in 1671, but this attack would be followed by many others. Wukalina fell in 1672, the first mainland city to be occupied; close to Truwana, and with difficult hills separating it from other cities, it was easier for the Pakanga to occupy than for others to defend. The same fate befell the small Kurnawal city of Larapuna in 1673. In the same year, the isolated Kurnawal city of Jangani [Cockle Creek] fell. This was a strongly-fortified city held by a renegade group of Kurnawal who did not acknowledge their king. It had proven impossible for the Kurnawal monarchs to re-establish control, over several decades, but the Pakanga conquered it by stealth, as they so often did.

The Pakanga assaults grew ever stronger throughout most the decade. Beleaguered, often attacked, and difficult to reinforce, Dawn Dunes eventually fell in 1675. Some other coastal Tjunini cities were captured for varying periods – Kwamania fell twice – but were recaptured in time. For the Kurnawal, Orange Rock was occupied for several months in 1674, and again for a few months over 1675-1676, although they eventually recaptured it on both occasions. While some cities could be reconquered easily, Dawn Dunes, Wukalina and Larapuna proved impossible to reconquer for a long time, since they were too easily reinforced by Pakanga.

The plagues, the many scourges of the Time of the Great Dying, continued even during the worst of the Pakanga raids. Bloat-throat [diphtheria] burned through the Cider Isle between 1673-1674, followed by an outbreak of death-cough [pertussis / whooping cough] in 1676-7. In what they did not realise was a stroke of great fortune, the relative handful of people who later died from scar-blister [smallpox, Variola minor] in 1682-3 were far fewer than those who would have been killed had the Cider Isle’s first outbreak been the deadlier variant [Variola major] of the disease.

Between the plagues and the seemingly-endless Pakanga raids, the Tjunini and Kurnawal found themselves severely short of manpower. By 1676, their position looked dire. The northeast of the island was firmly under Pakanga rule – Orange Rock had not yet been reconquered – and every month seemed to bring more Pakanga across the Gray Sea [Tasman Sea]. In desperation, Kings Wurangkili and Narawntapu turned to new sources of manpower: the Pakanga themselves.

The Pakanga were not a united group, being divided both by old inter-iwi hatreds and more recent religious wars between Catholic, Plirite and traditionalists. The occupiers of the Narrow Sea islands were traditionalists, and most of the Pakanga who raided the Cider Isle were of the same faith, together with smaller numbers of Catholics. The Tjunini and Kurnawal monarchs chose to recruit Pakanga of their own, preferably Plirite, to aid them in their struggles against the would-be conquerors [10].

Some of these recruitment efforts involved promises of land grants for the new Pakanga. This marked the true level of desperation amongst the Cider Isle’s peoples, for they traditionally viewed their land as sacred and not to be given to any other people but their own. Under this pressure, however, the Kurnawal offered land grants around Orange Rock to Pakanga mercenaries, so that they could recapture the city and then defend it afterward. The Tjunini offered similar land grants around their most hard-pressed cities of Kwamania and Hope Hill [Stanley], in exchange for defending against other raiders. In other cases, Pakanga were recruited simply as mercenaries, lured both by pay and by careful choice of iwi that were rivals to those now threatening the Cider Isle. At various times, the Dutch, British and Nuttana all assisted in transporting Pakanga to aid the Cider Isle’s defenders.

With some Māori also acting as defenders, the Pakanga raids into the Cider Isle were much less successful. The Pakanga did occupy some cities at times, but they did not make any further ongoing conquests. While raids continued into the 1680s, the actual Pakanga settlements were limited to the north-eastern corner of the Big Island, together with distant and resilient Jangani in the south. During this time, the Harmony Wars were gradually ending in Aotearoa, which cut off the supply of fresh Pakanga raiders.

By 1685, it appeared that the external Pakanga threat was finally over. Launching a full reconquest of the new Māori regions, however, would prove to be more difficult. With the foreign menace receding, neither Tjunini nor Kurnawal properly trusted the other to cooperate in expelling the interlopers, fearing betrayal. The Kurnawal did succeed in expelling the Pakanga from Jangani in 1687, with some of the defenders betraying their comrades in exchange for land grants, and the rest of the defenders sold as slaves to the Nuttana.

In 1688-9 the Tjunini and Kurnawal finally launched a joint reconquest of Dawn Dunes. When the city fell, King Wurangkili proclaimed that the city had to be restored to him as his ancient birthright. King Narawntapu responded by negotiating vassalage for the remaining Pakanga in Wukalina and Larapuna; recognising that since those towns had been flooded by Pakanga driven out from Dawn Dunes, reconquering the region was a practical impossibility anyway. The Kurnawal monarch had himself declared the ariki iwi of the Māori in the north-east, and recognised the rule of the ariki hapū beneath him.

With these events, the immediate dangers had gone, but the peoples of the Cider Isle had been gravely weakened by plague and warfare, and vulnerable to further pressure from abroad.

* * *

In the wider world, the 1660s and 1670s (and early 1680s) were marked by the Anglo- Dutch Wars, struggles that were fought principally in Europe but with conflicts that touched much of the globe. These struggles gave the indigenous peoples of the Third World some respite from the colonial pressure that had applied in previous decades.

By the end of the Anglo-Dutch Wars, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) and East India Company (EIC) had tacitly agreed to partition much of the Orient into spheres of influence, where they would not interfere with each other. The East Indies went to the VOC, while India and the whole subcontinent (except for a Dutch presence in parts of cinnamon-rich Ceylon) became the preserve of the EIC. Each company allowed the other a free hand in their allotted regions. The previous four decades of official and unofficial warfare had led the Lords Seventeen and Court of Directors each to judge that partition and steady if not overwhelming profits was better than squandering endless resources fighting each other.

In those allocated regions, the VOC and EIC focused their attention on curtailing the influence of the other colonial powers which had emerged (or re-emerged) while the Dutch and English were locked in the massive struggles of the Anglo-Dutch Wars: the French, the Portuguese, the Danes, and the Swedes. Where not combating those colonial rivals directly, they sought to re-establish their influence and trading connections with the local powers.

No such partition agreement applied in Aururia. Aururia had become the most valuable prize in the Oriental struggles of the two great trading companies. Gold, silver, kunduri, jeeree, and an abundance of novel spices ensured this competition. The best of those spices, sweet peppers and lemon verbena [lemon myrtle], were so valuable that they could even be traded to elsewhere in the Orient for greater profits; from the European perspective, much better than having to supply bullion from Europe. In such an environment, the Dutch and English made every effort to fight each other and gain control of the resources of the Third World.

This struggle played out in the Cider Isle as much as anywhere in the Third World. With the Anglo-Dutch Wars over and the Pakanga threat subsiding, the VOC and EIC resumed their struggle for influence in the Cider Isle, with the Compagnie d’Orient (CDO) [French East India Company] running interference. These companies’ determination grew ever greater with the weakening population; so many of the existing peoples of Aururia were declining with the Great Death and the plagues that followed during the Time of the Great Dying.

For while the population of the Third World was collapsing, the companies’ desire for trade goods was ever-expanding, particularly in sweet peppers which were required in ever-greater numbers to sustain their trade in the Orient and burgeoning European demand. The pre-contact Third World would have been capable of supplying any conceivable volume of European trade demand, but the ravages of plague and war had reduced most of that population, leading to huge foreign pressure on those who were left to supply this and other spices.

The Cider Isle had an excellent climate for growing the common varieties of sweet peppers; here the crops required little if any irrigation, unlike most of the accessible mainland areas [11]. As such, the VOC and EIC wanted to take as much control as needed to ensure that the survivors re-oriented their economy into production of spices, together with gold mining. The much-reduced population of the Cider Isle could not withstand this foreign influence. No formal protectorate may have been declared, but by 1690 the Kurnawal kingdom was an EIC client state in all but name. Likewise, the VOC sent enough arms and mercenaries to the Nine-Fold King that he became not only their effective vassal, but so that he could also break the old Tjunini political structure. Before, the Nine-Fold King had simply been the most prominent ruler but with vassal kings; under King Wurangkili and (after 1692) his son, the Nine-Fold King became the genuine ruler of all the Tjunini.

In such an environment, the old gum cider production almost, but not quite, vanished. The native peoples might still refer to their land as the Cider Isle, but this was not matched by their actual production, where it would have been more accurate to rename their homeland as the Pepper Isle. In such an environment, with European companies promoting production and mercenaries on hand where needed, the Tjunini and Kurnawal also sought to curtail destructive Palawa raids, and to expand their control into fresh fertile soils beyond their coastal territories. The few remaining Palawa retreated into the rugged terrain of the interior, where digging them out was more trouble than it was worth, unless the Palawa provoked retaliation through raids. (They mostly didn’t.)

As for the Tjunini and Kurnawal, despite their weakened population, despite further infighting risking direct European control, they did not stop fighting each other. Hostilities resumed in 1694-6, in what would be called the Unmaking War. This ended in a Kurnawal victory, allowing them to recapture Dawn Dunes. Of course, given the many wars between the two peoples, the odds were that the Tjunini would recapture the city soon enough.

* * *

[1] The mice that Bangalla refers to were in fact kiore, Polynesian rats, deposited there by previous Māori visitors to Penguin Island.

[2] That is, the Cape Barren goose (Cereopsis novaehollandiae), a grazing bird which is a useful source of both meat and eggs.

[3] The names for both Tayaritja (Flinders Island) and Truwana (Cape Barren Island) were in fact borrowed from the names which the Palawa gave to those islands. The Palawa still knew of those islands, even though they did not inhabit them.

[4] i.e. the War of the Princess, a struggle immortalised in song, and which possibly holds an elemental of historical truth. See post #13.

[5] This comes from a process using native indigo (Indigofera australis), a relative of true indigo (I. tinctoria). The Aururian species of indigo produces a similar blue-purple dye to true indigo, but with further treatment fibres that have already been dyed blue can be modified to a brighter green shade. To the Tjunini, this is the most valuable colour, royal green.

[6] A yamadi is a kind of collarless, V-neck shirt that is a common dress item amongst urban Kurnawal (and some Tjunini), but which is much plainer that would traditionally be worn by nobility, let alone royalty.

[7] The Kurnawal royal mace is not the only potential regalia they use, since the king also wears a plain gold coronet in formal settings. Having a mace made of brass is a sign of considerable wealth, since unlike their common bronze, brass must be imported, ultimately from the Tjibarri desert mines of Silver Hill [Broken Hill, NSW].

[8] See posts #94 and #95.

[9] Yellow Pine [Strahan] lies inside a large but shallow harbour that the Nangu call Timber Haven and which historically was called Macquarie Harbour. As could be guessed from the name, the Nangu use it as one of their main sources of timber for shipbuilding. The entrance to Timber Haven is extremely dangerous for visiting ships, since it is a narrow, shallow channel with dangerous currents, and whose depth often shifts depending on the deposits of sediment from the rivers that flow into the harbour. In this Pakanga raid, many ships were lost trying to get into and out of the harbour.

[10] The Tjunini and Kurnawal are themselves largely Plirite, having been converted by Nangu priests, although they retain some syncretic beliefs. This common religion has never stopped them from fighting each other.

[11] Sweet peppers (Tasmannia spp) are naturally alpine or cool temperate crops which require very high natural rainfall. Being further south, the Cider Isle is usually cool enough to sustain these crops even in coastal areas. The alpine areas of the mainland are equally capable of growing sweet peppers without needing irrigation, but these are far enough inland (and have poor roads) that transporting the crops to ports is much more difficult.

* * *

Thoughts?

Great post, makes one hope that there's some future yet for cooperation on the Cider isle. Speaking of the wider world, what's been going on in Java? At this particular period in history both Mataram and Banten are doing pretty well, and Indonesian military technology in general was fairly good. Have the Dutch had the same good luck in undermining the native states, or perhaps have Sultan Agung & friends had more success in resisting Dutch encroachment?

Kaiphranos

Donor

Hmm, the Tjunini and the Kurnawal managing to work together for once--that was unexpected. I was also surprised the "hire Pakanga to fight Pakanga" plan didn't spectacularly backfire, though I suppose with a continuing Maori presence there's still time for that.

I also wonder just how long the cycle of violence might continue--I don't find it hard to imagine a post-colonial Cider Island analogous to OTL Rwanda...

I also wonder just how long the cycle of violence might continue--I don't find it hard to imagine a post-colonial Cider Island analogous to OTL Rwanda...

twovultures

Donor

I feel sorry for the poor Palawa but after these retreats, hopefully they're left mostly alone in the agriculturally poor hinterland.

but after these retreats, hopefully they're left mostly alone in the agriculturally poor hinterland.

Loved the reference to DValdron's TL, by the way

Loved the reference to DValdron's TL, by the way

TheScottishMongol

Banned

Hmm, the Tjunini and the Kurnawal managing to work together for once--that was unexpected. I was also surprised the "hire Pakanga to fight Pakanga" plan didn't spectacularly backfire, though I suppose with a continuing Maori presence there's still time for that.

I also wonder just how long the cycle of violence might continue--I don't find it hard to imagine a post-colonial Cider Island analogous to OTL Rwanda...

Agreed, that seemed very risky, especially the bit about giving them land on the Cider Isle - I'm getting a heavy Turk vibe from that.

Kaiphranos

Donor

Agreed, that seemed very risky, especially the bit about giving them land on the Cider Isle - I'm getting a heavy Turk vibe from that.

I was thinking of the Saxons arriving as mercenaries in post-Roman Britain, but yeah--I suspect there are a number of other examples out there too.

TheScottishMongol

Banned

I was thinking of the Saxons arriving as mercenaries in post-Roman Britain, but yeah--I suspect there are a number of other examples out there too.

Yeah, that too. Or, to call upon a fictional reference, the arrival of the Andals in Westeros.

The point is, this strategy pretty much always leads to disaster.

Great post, makes one hope that there's some future yet for cooperation on the Cider isle. Speaking of the wider world, what's been going on in Java? At this particular period in history both Mataram and Banten are doing pretty well, and Indonesian military technology in general was fairly good. Have the Dutch had the same good luck in undermining the native states, or perhaps have Sultan Agung & friends had more success in resisting Dutch encroachment?

The Dutch have generally been quite good at exploiting internal divisions and rivalries between different monarchs. A strong ruler can certainly hold off Dutch influence for a while, and even sometimes push back in terms of territory. Sultan Agung did rather well while he lived, for instance. The fundamental problem is that with lots of vassals, and the potential for disputed succession, it was easy for the VOC to get more influence after his death.

By 1700 (if not earlier) the Dutch are the effective rulers of Java, in some cases directly, but mostly as protectorates and the like.

Hmm, the Tjunini and the Kurnawal managing to work together for once--that was unexpected. I was also surprised the "hire Pakanga to fight Pakanga" plan didn't spectacularly backfire, though I suppose with a continuing Maori presence there's still time for that.

Tjunini-Kurnawal cooperation was born of desperation, but was always likely to last as long as those monarchs were in charge; they were astute enough to recognise the costs of betrayal. Things may have been different if one of them had died while the Pakanga were still actively raiding.

As for the dangers of recruiting Pakanga, granting them land and so forth, the Tjunini and Kurnawal monarchs were making the best of a bad set of choices. They figured, correctly, that there few short-term risks. The Pakanga routinely fight each other, and the ones they recruited were from iwi who hated the ones doing the raiding. The chances of their defending Pakanga siding with the raiders were minimal. And offering land made it easier to recruit their own Pakanga, and gave those defenders an active interest in repelling the raiders.

In the long term, yes, there's all sorts of risks. But the Cider Isle monarchs figured, pretty much correctly, that without recruiting additional manpower, they didn't need to worry about the longer term, since the short term would see them conquered.

I also wonder just how long the cycle of violence might continue--I don't find it hard to imagine a post-colonial Cider Island analogous to OTL Rwanda...

Many other imponderables to consider between now and then, not least of which is whether the Cider Isle ends up under one colonial power or several. But a Rwanda analogue or a Yugoslavia analogue is certainly a possibility. On the positive side, a Belgium analogue might not be out of the question either.

I feel sorry for the poor Palawabut after these retreats, hopefully they're left mostly alone in the agriculturally poor hinterland.

The Palawa do have problems, although there's also the consideration that the agricultural peoples are still losing population - and, barring foreign settlement, will do so for about another four decades. So this may reduce the pressure on the Palawa.

Agreed, that seemed very risky, especially the bit about giving them land on the Cider Isle - I'm getting a heavy Turk vibe from that.

I was thinking of the Saxons arriving as mercenaries in post-Roman Britain, but yeah--I suspect there are a number of other examples out there too.

Yeah, that too. Or, to call upon a fictional reference, the arrival of the Andals in Westeros.

The point is, this strategy pretty much always leads to disaster.

The particular example I had in mind was the formation of Normandy, where the French crown gave territory to some Norsemen on the proviso that they protect against other attacking Norsemen. This worked in the short term, but may perhaps be said to have caused some longer term problems for France (see War, Hundred Years', and other such trifles.)

For some reason, I'm imagining the future of Aururia as several European protectorates, instead of colonies.

In the short term, yes, that's the most likely outcome. The colonial powers here are trading companies. They want to make a lot of money; they're not looking to found settlement colonies, spread Christianity at the point of a sword, or win land just to gain fancy titles. If they can get the trade access they want, and enough influence over the production of the desired trade goods, they will probably be satisfied with that. In the short term. They're not into conquest for the sake of conquest.

On the other hand, that's more or less how the VOC started in the East Indies in OTL, or the EIC started in India, but things didn't finish up quite like that.

For some reason, I'm imagining the future of Aururia as several European protectorates, instead of colonies.

That's what I think too.

The Dutch have generally been quite good at exploiting internal divisions and rivalries between different monarchs. A strong ruler can certainly hold off Dutch influence for a while, and even sometimes push back in terms of territory. Sultan Agung did rather well while he lived, for instance. The fundamental problem is that with lots of vassals, and the potential for disputed succession, it was easy for the VOC to get more influence after his death.

By 1700 (if not earlier) the Dutch are the effective rulers of Java, in some cases directly, but mostly as protectorates and the like.

That's a shame, though given the better finances of the VOC ITTL things were probably even more in their favour than OTL, where to be honest it was a pretty near run thing. More Europeans earlier in the 17th century before the Javanese had time to catch up (at least in terms of weapons) would do a number on them. I do wonder what the impact of Aururia will be on Java in the long run, and vice versa. Perhaps Plirism will make inroads? A common religion and a common foe...

That's a shame, though given the better finances of the VOC ITTL things were probably even more in their favour than OTL, where to be honest it was a pretty near run thing. More Europeans earlier in the 17th century before the Javanese had time to catch up (at least in terms of weapons) would do a number on them. I do wonder what the impact of Aururia will be on Java in the long run, and vice versa. Perhaps Plirism will make inroads? A common religion and a common foe...

The problem is that Java is already predominantly Islamic at this point.

The problem is that Java is already predominantly Islamic at this point.

That's true, and Abrahamics tend to be pretty hard to uproot, but I'm curently just thinking of things which would be fun, not necessarily particularly likely.

That's a shame, though given the better finances of the VOC ITTL things were probably even more in their favour than OTL, where to be honest it was a pretty near run thing. More Europeans earlier in the 17th century before the Javanese had time to catch up (at least in terms of weapons) would do a number on them.

It is unfortunate, but the VOC and EIC are both much wealthier than they were at the same stage in OTL, Aururian plagues notwithstanding. There's just so many more resources at their disposal now. The VOC will also have tried to use Pakanga mercenaries in Java too (as well as Europeans), although given the tropical diseases that probably won't have worked out so well.

I do wonder what the impact of Aururia will be on Java in the long run, and vice versa. Perhaps Plirism will make inroads? A common religion and a common foe...

The problem is that Java is already predominantly Islamic at this point.

That's true, and Abrahamics tend to be pretty hard to uproot, but I'm curently just thinking of things which would be fun, not necessarily particularly likely.

Regions which are already Muslim will most likely stay that way. It's not completely unknown for regions which were Muslim to change religion, but short of ethnic cleansing it's very unlikely, and I don't see any particular reason to think that would happen here. Those parts of OTL Indonesia and Papua New Guinea which were not yet Muslim might end up Plirite ITTL, but if I understand right those were mostly further east.

For other longer term effects, well, Aururian crops mostly don't grow in Java, though a few Javanese crops can grow in parts of Aururia (mostly the tropical regions). Aururian spices, though, will have some interesting effects on Javanese cuisine. So, to a lesser degree, will Javanese spices in Aururia. (Garlic!)

One consequence of this spice exchange will be quite important. In OTL, (true) peppers made up the majority of the spice trade by volume, although not necessarily by value. A lot of these peppers were produced in the East Indies, in this era in Banten and, later, in Aceh. (In the nineteenth century, Aceh provided over half of world pepper exports). This made pepper an important source of wealth for the various Javan and Sumatran states, allowing them to (for example) buy weapons.

ITTL, sweet peppers from Aururia are rapidly displacing this trade. To a certain degree, they are even being imported into Java and Sumatra, reversing this trade trend. This is going to affect the ability of the Javanese and Sumatran states to arm themselves, among other things.

In other aspects, well, much depends on the long-term fate of both regions. But (for instance) some form of cooperation in terms of anti-colonial movements may be a possibility.

On the map, part of the text says "more than a millenia". Oops. That should be "a millennium", of course.

Aside from that, great update, and very authentic looking map.

Aside from that, great update, and very authentic looking map.

On the map, part of the text says "more than a millenia". Oops. That should be "a millennium", of course.

Aside from that, great update, and very authentic looking map.

Oops - I just realised I should have made it clearer about the map. That was the original map that Ampersan created for LoRaG Tasmania, way back after post #13 (original link here). All I did was add a link to where that map is currently stored on the DoD/LoRaG website. On reflection, I should have made it explicit that I was using the original map.

Anyway, speaking of maps, the next post (#99) won't have any new ones, since it's about the Atjuntja and most of the details are already clear. But someone is thankfully helping me with a map what will show (most of) Aururia and Aotearoa circa 1700, which is good timing since that's what post #100 is about - a broad overview of where things have gotten up to by 1700.

Threadmarks

View all 71 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Lands of Red and Gold #122: A Man Of Vision Lands of Red and Gold #123: What Becomes Of Dominion Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #5.5: Interview With The Eʃquire Lands of Red and Gold is now published! Aururian Fire Management Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #15: Into Darkness Contest - Guess The Character Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #16: Minutes Take Hours

Share: