McCarthy is alive, Stalin diedDamn so much happened here. Joe McCarthy dying, Lodge getting the VP slot and now Taft having cancer. I like how you had Lodge be Douglas McCarthy's running mate a more Liberal Republican to counter McCarthy's more extreme decisions. Should be good

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Patton in Korea/MacArthur in the White House

- Thread starter BiteNibbleChomp

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Nah, there's still tons of unexploded shells. To the point they have a Red Zone, to say nothing about the annual Iron Harvest. Missing a mine or two is possible.

Italy has been declared mine free only in 1998 and we are still find WWI and II bombshell, even in the middle of a city

Thanks I'll fix thatMcCarthy is alive, Stalin is dead

Thought it fit more to have him fade away from the story, just like in the movieWhat? No in-universe reactions to Patton's death?

- BNC

Oh come on!Thought it fit more to have him fade away from the story, just like in the movie

- BNC

What am I supposed to say? I mean, it's possible I could have written a 500 word long piece about how Eisenhower breathed a seven year long sigh of relief because he wouldn't have to endure Patton's drama on the radio any more... not sure that really adds anything to the story thoOh come on!

- BNC

140 word obituary from the local newspaper was about all i expected it is the title character even if its only abojut how he has changed the word and not him itself

Interesting thought would be if the USSR took MacArthur being elected as a sign of a military coup and purged the military again or the military fearing another purging because the Politburo thinks they are going to launch a coup end up actually doing so to head them off at the pass and we end up with Zhukov or someone in charge.

Well, perhaps and as an optional thing, if you allowed me this suggestion: I think that if you so decided, that you could write some lines from some, TTL's newspaper excerpts with condolences declarations or telegrams transcriptions from two or three TTL' s main characters as Rhee, Truman, MacArthur, Marshall and/or Eisenhower... But, of course the final decision and the story are yours...What am I supposed to say? I mean, it's possible I could have written a 500 word long piece about how Eisenhower breathed a seven year long sigh of relief because he wouldn't have to endure Patton's drama on the radio any more... not sure that really adds anything to the story tho

- BNC

All true, and he's not going to be Stalin's successor ITTL. He'd still be perceived to be powerful enough at this time that Acheson would mention it though.Beria is never going to be leader of the Soviet union he was hated by everyone in the leadership. This is not just because he was Head of the secret police he was also a serial rapist who alienated some of the most important people in the party thanks to his proclivities.

Interesting takeInteresting thought would be if the USSR took MacArthur being elected as a sign of a military coup and purged the military again or the military fearing another purging because the Politburo thinks they are going to launch a coup end up actually doing so to head them off at the pass and we end up with Zhukov or someone in charge.

Suggestions are always welcome! Unfortunately I probably won't get around to this one... as I mentioned above it doesn't exactly fit the whole 'fade away' idea I felt most appropriate for Patton, and as things are I'm not getting enough time to work on the TL as I would like (real lifeWell, perhaps and as an optional thing, if you allowed me this suggestion: I think that if you so decided, that you could write some lines from some, TTL's newspaper excerpts with condolences declarations or telegrams transcriptions from two or three TTL' s main characters as Rhee, Truman, MacArthur, Marshall and/or Eisenhower... But, of course the final decision and the story are yours...

Now you've made me wonder what Patton's Twitter account might look like if he was able to have one. Thanks for that image, not sure how I'm supposed to feel about it140 word obituary from the local newspaper was about all i expected it is the title character even if its only abojut how he has changed the word and not him itself

- BNC

That would only make it more obvious that he'd had him killed. Or someone else had.What am I supposed to say? I mean, it's possible I could have written a 500 word long piece about how Eisenhower breathed a seven year long sigh of relief because he wouldn't have to endure Patton's drama on the radio any more... not sure that really adds anything to the story tho

- BNC

patton would have followed the directives of the Chiefs of Staff, just as ridgeway did.I came to this site to start a thread saying we would've won the Korean War if Patton had been the commander. Patton would've pursued an aggressive strategy instead of parking the Army on the 38th parallel for 2 years the way Matthew Ridgeway did.

Part IV, Chapter 32

CHAPTER 32

The results of the Republican National Convention loomed large when the Democrats held their own National Convention on the 21st of July. The Republicans had been the first to televise the entire event, and the Democratic Party had watched it carefully. Some of this information would help them set up their own campaign: they too would hold the Convention at the International Amphitheatre, and less flattering camera angles could be reconsidered in the hopes of making a better event for those watching from home. Holding the second convention would also give them more information on their opposition’s campaign: whoever they nominated would have to be the best person to challenge MacArthur and Lodge.

When the Convention began, Tennessee’s Senator Estes Kefauver was the frontrunner, having twelve primary races to his name, although this only translated to around a quarter of the 1230 delegates voting in the first ballot. Kefauver’s supporters, like MacArthur’s two weeks prior, argued that he was the popular choice and therefore the best candidate to go against the incredibly popular general.

The party bosses were inclined to disagree. Kefauver, they said, was a maverick and a loose cannon, who would be too dangerous in the nation’s top job. Many of them proposed instead Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, an outspoken supporter of segregation (though never one to use such explicit terms himself) who even Northern Democrats saw as too racist to have a chance at winning. “MacArthur’s going to be bashing him with the civil rights stick for the next four months” was the prediction of one delegate. Another noticed that MacArthur had scarcely campaigned south of the Mason-Dixon line in months, and suggested that the party look to someone with more national appeal instead of placing their focus in the one region the Democrats were most likely to win.

Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, who had placed a close third in the first ballot, emerged as that person. Stevenson, a political moderate, had the support of Western and Northeastern states, regions that MacArthur was known to be targeting. He was known to be a gifted orator, which could not hurt against the charismatic MacArthur. Perhaps most importantly, most of the other alternatives had some sort of weakness that would inevitably be used against them. Stevenson’s record was clean.

The choice for Stevenson’s running mate would prove to be just as heavily debated. President Truman, although not popular with the public, still held a great deal of influence over the party, had picked Stevenson long ago, and now his choice for the running mate was Alabama’s John Sparkman. While most of the Southern delegates agreed, the same civil rights argument used against Richard Russell applied just as well to Sparkman as well. Averell Harriman’s name was also put forward, but his lack of political experience made many delegates unwilling to support him. Kefauver’s name was raised again, and many delegates were swayed when one supporter gave an impassioned plea: “four Americans in every five believe we have already lost this election, and yet here we are saying Senator Kefauver is too great a risk. Perhaps what the Democratic Party needs is a big risk.”

A majority of the delegates, sensing no better alternative, announced that they would support Kefauver for vice president, completing the Democratic ticket.

Contrary to the expectations of the Democrats who chose him, Stevenson would prove to be rather weak on the campaign trail. His celebrated speaking skills resulted only in graceful, long discussions of policy and scripture more expected of a professor than a politician, making him seem out of touch while also lacking the dramatic flair that often accompanied MacArthur’s speeches. In his discussions on policy, instead of spending his time on the expanded social welfare programs and anti-crime measures that set his platform apart from the Republicans, he dwelled on his plans to repeal the Taft-Hartley Act, which was something MacArthur had been vocal about for months (although MacArthur said he would “review” the act rather than repeal it in its entirety).

Then in September, Stevenson would go on to make his biggest mistake in his campaign, when he claimed that MacArthur would “not be the best man to lead America’s foreign policy”. His argument was intended to criticise MacArthur’s proposed focus on Asia, and not Europe, as the central theatre in the Cold War, but when he followed the statement up not with a discussion about the Soviet Union and instead with a pledge to merely increase defence spending by a modest amount, he came out looking foolish. MacArthur had spent the last decade as the face of American foreign policy in Asia, and had more experience in the region than just about anyone, while Stevenson’s greatest foreign policy accomplishment was a 1944 report on the state of the Italian economy. MacArthur had also reminded voters time and again that Red China had intervened in Korea and attacked American soldiers, while the Soviets had stayed out, making the Chinese seem like a greater threat to America’s security. Stevenson, MacArthur contended, just wanted to continue Truman’s policy, and wasn’t Truman’s policy what had brought about Korea in the first place?

***

MacArthur did not show any particular emotion upon hearing that Stevenson had been nominated. As far as he was concerned, winning the Republican nomination had just about put him in the White House, a view only reinforced by Stevenson’s weak showing on the campaign trail. His priority now was not worrying about the Democrats: they had already failed, but on finding the men that would make up his administration.

He had no shortage of loyal followers to choose from. Some, like Pat Echols, had come with him directly from Tokyo. Others, especially Phil LaFollette, would come from his campaign team. Most of what critics called the ‘Bataan gang’, including men who had been with him since the 1930s, had stayed back in Japan to assist Ridgway in the final stages of the occupation, and were now retiring from the Army to follow their hero in civilian life. Charles Willoughby had scored a CIA job. MacArthur’s ever-present legal pad, once used to give out orders in Japan, now contained a list of positions for advisors, cabinet members, and other important jobs. By the beginning of August, nearly every one of them had a name written next to it. Most of the names had been worshipping MacArthur for years.

Yet one position that would prove to be especially important in MacArthur’s presidency wasn’t even on the list. That position would be titled ‘Special Advisor to the President’.

The Special Advisor spot has its origins in an offer Harry Truman made to MacArthur and Stevenson in the middle of August 1952. Truman remembered well how poorly he had been prepared for the presidency. He had been vice president for less than three months, and had hardly known FDR, when he was expected to fill the great man’s shoes, and big shoes they had been. Remembering the difficulty of his own transition, Truman resolved to make it as easy as possible for his successor, even if his successor turned out to be His Majesty MacArthur. So he invited the two nominees to lunch with him at the White House, meet his cabinet and be briefed on matters foreign and domestic that would be of use to an incoming administration.

MacArthur noticed that even if this was a good-faith offer, which indeed it was, there would be strings attached. To be briefed implied that he needed briefing, an image that would not do. He was running to replace Truman’s foreign policy failures, not to embrace them. Any information he needed, he could get from Charles Willoughby. And by being photographed alongside Truman, wouldn’t that risk tying him to Truman’s pathetic legacy? So, much to Truman’s disappointment (if not his surprise), MacArthur declined the offer.

Frederick Ayer Jr had advised MacArthur to meet with Truman, but ever since Ned Almond had returned from Tokyo, MacArthur had stopped listening to his campaign manager whenever his former chief of staff offered a different opinion. Almond was just as terrible to deal with as his late uncle had said: whenever you wanted to see MacArthur, you had to go through Almond, and Almond didn’t let anyone through unless they were as much of a crony as he. Patton had outranked Almond, and had the guts to curse out the man until he got MacArthur’s ear directly (at least until MacArthur found a subordinate Patton was willing to deal with in Doyle Hickey), so he had been the one person able to get around the chief of staff. Without the protection of rank, that method wouldn’t work here.

Ayer knew that allowing the Bataan gang to dictate the flow of information to MacArthur would result in disaster eventually: their constant interference and incompetence had caused many setbacks on MacArthur’s battlefields. Furthermore, although MacArthur had effectively ruled Japan for six years, Ayer knew there were many differences between acting as a military governor and serving as the US President, and it did not help that, before this campaign, he had not been in the country for fifteen years. Even if MacArthur would not listen to Truman, he would be well served by an advisor who could prepare him for the job.

Ayer thought the best person would be Herbert Hoover. Hoover was a known MacArthur admirer, who had last year described the general as “a reincarnation of St. Paul into a great General of the Army who came out of the East”. Hoover had been President before, and knew the ins and outs of the office, so his advice could be supported by that experience. Most importantly, Hoover was one of the few people MacArthur looked up to. Most Americans would have placed Hoover as one of the worst Presidents, but MacArthur rated him as one of the top four. So Ayer wrote to Hoover asking if he would meet with MacArthur. Hoover agreed, and MacArthur was delighted by the news that Hoover was inviting him to lunch.

Hoover would not be the only late addition to the MacArthur team. The list on the general’s legal pad still had one important slot that remained frustratingly bare even as September dawned. MacArthur had spent days wondering, and had yet to come up with a suitable answer to the question: who would be his Secretary of Defence?

The need for civilians to control the military meant that any potential Secretary of Defence could not have served in the armed forces within the last ten years, precluding any Korean veterans and just about everyone from World War II, and indeed just about everyone from MacArthur’s inner circle. The Senate could grant an exception to this rule - they had for George Marshall - but as he was a general himself that wasn’t likely to happen. Senator Knowland, one of MacArthur’s strongest supporters and a man he had once considered as a potential running mate, happened to be a World War II veteran, ruling him out. Another vocal supporter, Kenneth Wherry, was perceived by MacArthur to be too isolationist, and wished to remain in the Senate besides. So MacArthur was forced to go on a weeks-long hunt.

He would find who he was looking for on a campaign tour of the Pacific Northwest.

MacArthur had long been impressed with the Air Force, having been a childhood friend of the pioneer Billy Mitchell (in whose court-martial MacArthur claimed to be the sole ‘not guilty’ vote). MacArthur had built his campaign in the Southwest Pacific around the capture of land-based airfields, and heaped praise upon his subordinate George Kenney when this proved successful. In Korea, the Air Force had sent the first Americans into combat in that war, and the strategic bombing of North Korea was so successful that it had to be called off for lack of targets less than a month after it began. The Air Force, MacArthur sensed, would be at the forefront of any future conflict, and therefore the front of the MacArthur defence policy, with the strategic bomber leading the way.

Nothing captured that vision better than the B-52. Still in an early testing phase of development, the B-52 looked promising: it could carry thirty tons of bombs, including an atomic weapon if need be, and it had the range to cover a continent and return without needing to refuel. He had been so impressed that he asked for a tour of the Boeing plant in Seattle, where he would meet the man behind the bomber.

William M. Allen was a man of big ideas. He had become President of Boeing in 1945, just as the war orders were drying up, and quickly pushed for the company to develop passenger aircraft alongside the heavy bombers it had become known for, and just months ago he had claimed to “bet the company” on the innovative 367-80 prototype that could one day become a jet-powered airliner. Boeing wasn’t quite a military company, but it came close, and Allen’s experience could be useful in Defence. Most importantly, he and MacArthur shared a great vision of the future of air power. By the end of the day, MacArthur had decided he wanted Allen on his team. Allen would take some convincing, but eventually agreed to serve as MacArthur’s Defence Secretary if confirmed by the Senate. The legal pad had its last spot filled.

***

November 5, 1952

Harry Truman folded the Chicago Daily Tribune and put the paper down on the Resolute Desk. Election Day had come and gone. Last time, the Tribune had printed arguably its most famous headline. He only wished that ‘AMERICA BACKS MAC’ was just as erroneous a line as Dewey defeating him had been. It wasn’t. It was never going to be. In 1948, his campaign had pulled off an upset by being energetic where Dewey’s was lacklustre. This time around, Stevenson had been the disappointment.

The results were the landslide everyone had predicted. The paper didn’t call any of the close races: those were still being counted, but none of them mattered any more. His Majesty had swept the Midwest, New England and California. When New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio were all called for MacArthur in the early hours of the morning, his victory was assured. The only question left was the margin, and with Stevenson hardly making an impression outside of the South, and with Florida proving surprisingly competitive, even that looked to be a great victory for the general who had caused the current president so much trouble.

So this is how my legacy comes to an end. Truman thought. God help us.

END OF PART IV

- BNC

The results of the Republican National Convention loomed large when the Democrats held their own National Convention on the 21st of July. The Republicans had been the first to televise the entire event, and the Democratic Party had watched it carefully. Some of this information would help them set up their own campaign: they too would hold the Convention at the International Amphitheatre, and less flattering camera angles could be reconsidered in the hopes of making a better event for those watching from home. Holding the second convention would also give them more information on their opposition’s campaign: whoever they nominated would have to be the best person to challenge MacArthur and Lodge.

When the Convention began, Tennessee’s Senator Estes Kefauver was the frontrunner, having twelve primary races to his name, although this only translated to around a quarter of the 1230 delegates voting in the first ballot. Kefauver’s supporters, like MacArthur’s two weeks prior, argued that he was the popular choice and therefore the best candidate to go against the incredibly popular general.

The party bosses were inclined to disagree. Kefauver, they said, was a maverick and a loose cannon, who would be too dangerous in the nation’s top job. Many of them proposed instead Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, an outspoken supporter of segregation (though never one to use such explicit terms himself) who even Northern Democrats saw as too racist to have a chance at winning. “MacArthur’s going to be bashing him with the civil rights stick for the next four months” was the prediction of one delegate. Another noticed that MacArthur had scarcely campaigned south of the Mason-Dixon line in months, and suggested that the party look to someone with more national appeal instead of placing their focus in the one region the Democrats were most likely to win.

Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, who had placed a close third in the first ballot, emerged as that person. Stevenson, a political moderate, had the support of Western and Northeastern states, regions that MacArthur was known to be targeting. He was known to be a gifted orator, which could not hurt against the charismatic MacArthur. Perhaps most importantly, most of the other alternatives had some sort of weakness that would inevitably be used against them. Stevenson’s record was clean.

The choice for Stevenson’s running mate would prove to be just as heavily debated. President Truman, although not popular with the public, still held a great deal of influence over the party, had picked Stevenson long ago, and now his choice for the running mate was Alabama’s John Sparkman. While most of the Southern delegates agreed, the same civil rights argument used against Richard Russell applied just as well to Sparkman as well. Averell Harriman’s name was also put forward, but his lack of political experience made many delegates unwilling to support him. Kefauver’s name was raised again, and many delegates were swayed when one supporter gave an impassioned plea: “four Americans in every five believe we have already lost this election, and yet here we are saying Senator Kefauver is too great a risk. Perhaps what the Democratic Party needs is a big risk.”

A majority of the delegates, sensing no better alternative, announced that they would support Kefauver for vice president, completing the Democratic ticket.

Contrary to the expectations of the Democrats who chose him, Stevenson would prove to be rather weak on the campaign trail. His celebrated speaking skills resulted only in graceful, long discussions of policy and scripture more expected of a professor than a politician, making him seem out of touch while also lacking the dramatic flair that often accompanied MacArthur’s speeches. In his discussions on policy, instead of spending his time on the expanded social welfare programs and anti-crime measures that set his platform apart from the Republicans, he dwelled on his plans to repeal the Taft-Hartley Act, which was something MacArthur had been vocal about for months (although MacArthur said he would “review” the act rather than repeal it in its entirety).

Then in September, Stevenson would go on to make his biggest mistake in his campaign, when he claimed that MacArthur would “not be the best man to lead America’s foreign policy”. His argument was intended to criticise MacArthur’s proposed focus on Asia, and not Europe, as the central theatre in the Cold War, but when he followed the statement up not with a discussion about the Soviet Union and instead with a pledge to merely increase defence spending by a modest amount, he came out looking foolish. MacArthur had spent the last decade as the face of American foreign policy in Asia, and had more experience in the region than just about anyone, while Stevenson’s greatest foreign policy accomplishment was a 1944 report on the state of the Italian economy. MacArthur had also reminded voters time and again that Red China had intervened in Korea and attacked American soldiers, while the Soviets had stayed out, making the Chinese seem like a greater threat to America’s security. Stevenson, MacArthur contended, just wanted to continue Truman’s policy, and wasn’t Truman’s policy what had brought about Korea in the first place?

***

MacArthur did not show any particular emotion upon hearing that Stevenson had been nominated. As far as he was concerned, winning the Republican nomination had just about put him in the White House, a view only reinforced by Stevenson’s weak showing on the campaign trail. His priority now was not worrying about the Democrats: they had already failed, but on finding the men that would make up his administration.

He had no shortage of loyal followers to choose from. Some, like Pat Echols, had come with him directly from Tokyo. Others, especially Phil LaFollette, would come from his campaign team. Most of what critics called the ‘Bataan gang’, including men who had been with him since the 1930s, had stayed back in Japan to assist Ridgway in the final stages of the occupation, and were now retiring from the Army to follow their hero in civilian life. Charles Willoughby had scored a CIA job. MacArthur’s ever-present legal pad, once used to give out orders in Japan, now contained a list of positions for advisors, cabinet members, and other important jobs. By the beginning of August, nearly every one of them had a name written next to it. Most of the names had been worshipping MacArthur for years.

Yet one position that would prove to be especially important in MacArthur’s presidency wasn’t even on the list. That position would be titled ‘Special Advisor to the President’.

The Special Advisor spot has its origins in an offer Harry Truman made to MacArthur and Stevenson in the middle of August 1952. Truman remembered well how poorly he had been prepared for the presidency. He had been vice president for less than three months, and had hardly known FDR, when he was expected to fill the great man’s shoes, and big shoes they had been. Remembering the difficulty of his own transition, Truman resolved to make it as easy as possible for his successor, even if his successor turned out to be His Majesty MacArthur. So he invited the two nominees to lunch with him at the White House, meet his cabinet and be briefed on matters foreign and domestic that would be of use to an incoming administration.

MacArthur noticed that even if this was a good-faith offer, which indeed it was, there would be strings attached. To be briefed implied that he needed briefing, an image that would not do. He was running to replace Truman’s foreign policy failures, not to embrace them. Any information he needed, he could get from Charles Willoughby. And by being photographed alongside Truman, wouldn’t that risk tying him to Truman’s pathetic legacy? So, much to Truman’s disappointment (if not his surprise), MacArthur declined the offer.

Frederick Ayer Jr had advised MacArthur to meet with Truman, but ever since Ned Almond had returned from Tokyo, MacArthur had stopped listening to his campaign manager whenever his former chief of staff offered a different opinion. Almond was just as terrible to deal with as his late uncle had said: whenever you wanted to see MacArthur, you had to go through Almond, and Almond didn’t let anyone through unless they were as much of a crony as he. Patton had outranked Almond, and had the guts to curse out the man until he got MacArthur’s ear directly (at least until MacArthur found a subordinate Patton was willing to deal with in Doyle Hickey), so he had been the one person able to get around the chief of staff. Without the protection of rank, that method wouldn’t work here.

Ayer knew that allowing the Bataan gang to dictate the flow of information to MacArthur would result in disaster eventually: their constant interference and incompetence had caused many setbacks on MacArthur’s battlefields. Furthermore, although MacArthur had effectively ruled Japan for six years, Ayer knew there were many differences between acting as a military governor and serving as the US President, and it did not help that, before this campaign, he had not been in the country for fifteen years. Even if MacArthur would not listen to Truman, he would be well served by an advisor who could prepare him for the job.

Ayer thought the best person would be Herbert Hoover. Hoover was a known MacArthur admirer, who had last year described the general as “a reincarnation of St. Paul into a great General of the Army who came out of the East”. Hoover had been President before, and knew the ins and outs of the office, so his advice could be supported by that experience. Most importantly, Hoover was one of the few people MacArthur looked up to. Most Americans would have placed Hoover as one of the worst Presidents, but MacArthur rated him as one of the top four. So Ayer wrote to Hoover asking if he would meet with MacArthur. Hoover agreed, and MacArthur was delighted by the news that Hoover was inviting him to lunch.

Hoover would not be the only late addition to the MacArthur team. The list on the general’s legal pad still had one important slot that remained frustratingly bare even as September dawned. MacArthur had spent days wondering, and had yet to come up with a suitable answer to the question: who would be his Secretary of Defence?

The need for civilians to control the military meant that any potential Secretary of Defence could not have served in the armed forces within the last ten years, precluding any Korean veterans and just about everyone from World War II, and indeed just about everyone from MacArthur’s inner circle. The Senate could grant an exception to this rule - they had for George Marshall - but as he was a general himself that wasn’t likely to happen. Senator Knowland, one of MacArthur’s strongest supporters and a man he had once considered as a potential running mate, happened to be a World War II veteran, ruling him out. Another vocal supporter, Kenneth Wherry, was perceived by MacArthur to be too isolationist, and wished to remain in the Senate besides. So MacArthur was forced to go on a weeks-long hunt.

He would find who he was looking for on a campaign tour of the Pacific Northwest.

MacArthur had long been impressed with the Air Force, having been a childhood friend of the pioneer Billy Mitchell (in whose court-martial MacArthur claimed to be the sole ‘not guilty’ vote). MacArthur had built his campaign in the Southwest Pacific around the capture of land-based airfields, and heaped praise upon his subordinate George Kenney when this proved successful. In Korea, the Air Force had sent the first Americans into combat in that war, and the strategic bombing of North Korea was so successful that it had to be called off for lack of targets less than a month after it began. The Air Force, MacArthur sensed, would be at the forefront of any future conflict, and therefore the front of the MacArthur defence policy, with the strategic bomber leading the way.

Nothing captured that vision better than the B-52. Still in an early testing phase of development, the B-52 looked promising: it could carry thirty tons of bombs, including an atomic weapon if need be, and it had the range to cover a continent and return without needing to refuel. He had been so impressed that he asked for a tour of the Boeing plant in Seattle, where he would meet the man behind the bomber.

William M. Allen was a man of big ideas. He had become President of Boeing in 1945, just as the war orders were drying up, and quickly pushed for the company to develop passenger aircraft alongside the heavy bombers it had become known for, and just months ago he had claimed to “bet the company” on the innovative 367-80 prototype that could one day become a jet-powered airliner. Boeing wasn’t quite a military company, but it came close, and Allen’s experience could be useful in Defence. Most importantly, he and MacArthur shared a great vision of the future of air power. By the end of the day, MacArthur had decided he wanted Allen on his team. Allen would take some convincing, but eventually agreed to serve as MacArthur’s Defence Secretary if confirmed by the Senate. The legal pad had its last spot filled.

***

November 5, 1952

Harry Truman folded the Chicago Daily Tribune and put the paper down on the Resolute Desk. Election Day had come and gone. Last time, the Tribune had printed arguably its most famous headline. He only wished that ‘AMERICA BACKS MAC’ was just as erroneous a line as Dewey defeating him had been. It wasn’t. It was never going to be. In 1948, his campaign had pulled off an upset by being energetic where Dewey’s was lacklustre. This time around, Stevenson had been the disappointment.

The results were the landslide everyone had predicted. The paper didn’t call any of the close races: those were still being counted, but none of them mattered any more. His Majesty had swept the Midwest, New England and California. When New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio were all called for MacArthur in the early hours of the morning, his victory was assured. The only question left was the margin, and with Stevenson hardly making an impression outside of the South, and with Florida proving surprisingly competitive, even that looked to be a great victory for the general who had caused the current president so much trouble.

So this is how my legacy comes to an end. Truman thought. God help us.

END OF PART IV

- BNC

Last edited:

Deleted member 2186

I do wonder if having MacArthur in the White House will be a good thing for the Cold War.CHAPTER 32

The results of the Republican National Convention loomed large when the Democrats held their own National Convention on the 21st of July. The Republicans had been the first to televise the entire event, and the Democratic Party had watched it carefully. Some of this information would help them set up their own campaign: they too would hold the Convention at the International Amphitheatre, and less flattering camera angles could be reconsidered in the hopes of making a better event for those watching from home. Holding the second convention would also give them more information on their opposition’s campaign: whoever they nominated would have to be the best person to challenge MacArthur and Lodge.

When the Convention began, Tennessee’s Senator Estes Kefauver was the frontrunner, having twelve primary races to his name, although this only translated to around a quarter of the 1230 delegates voting in the first ballot. Kefauver’s supporters, like MacArthur’s two weeks prior, argued that he was the popular choice and therefore the best candidate to go against the incredibly popular general.

The party bosses were inclined to disagree. Kefauver, they said, was a maverick and a loose cannon, who would be too dangerous in the nation’s top job. Many of them proposed instead Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, an outspoken supporter of segregation (though never one to use such explicit terms himself) who even Northern Democrats saw as too racist to have a chance at winning. “MacArthur’s going to be bashing him with the civil rights stick for the next four months” was the prediction of one delegate. Another noticed that MacArthur had scarcely campaigned south of the Mason-Dixon line in months, and suggested that the party look to someone with more national appeal instead of placing their focus in the one region the Democrats were most likely to win.

Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, who had placed a close third in the first ballot, emerged as that person. Stevenson, a political moderate, had the support of Western and Northeastern states, regions that MacArthur was known to be targeting. He was known to be a gifted orator, which could not hurt against the charismatic MacArthur. Perhaps most importantly, most of the other alternatives had some sort of weakness that would inevitably be used against them. Stevenson’s record was clean.

The choice for Stevenson’s running mate would prove to be just as heavily debated. President Truman, although not popular with the public, still held a great deal of influence over the party, had picked Stevenson long ago, and now his choice for the running mate was Alabama’s John Sparkman. While most of the Southern delegates agreed, the same civil rights argument used against Richard Russell applied just as well to Sparkman as well. Averell Harriman’s name was also put forward, but his lack of political experience made many delegates unwilling to support him. Kefauver’s name was raised again, and many delegates were swayed when one supporter gave an impassioned plea: “four Americans in every five believe we have already lost this election, and yet here we are saying Senator Kefauver is too great a risk. Perhaps what the Democratic Party needs is a big risk.”

A majority of the delegates, sensing no better alternative, announced that they would support Kefauver for vice president, completing the Democratic ticket.

Contrary to the expectations of the Democrats who chose him, Stevenson would prove to be rather weak on the campaign trail. His celebrated speaking skills resulted only in graceful, long discussions of policy and scripture more expected of a professor than a politician, making him seem out of touch while also lacking the dramatic flair that often accompanied MacArthur’s speeches. In his discussions on policy, instead of spending his time on the expanded social welfare programs and anti-crime measures that set his platform apart from the Republicans, he dwelled on his plans to repeal the Taft-Hartley Act, which was something MacArthur had been vocal about for months (although MacArthur said he would “review” the act rather than repeal it in its entirety).

Then in September, Stevenson would go on to make his biggest mistake in his campaign, when he claimed that MacArthur would “not be the best man to lead America’s foreign policy”. His argument was intended to criticise MacArthur’s proposed focus on Asia, and not Europe, as the central theatre in the Cold War, but when he followed the statement up not with a discussion about the Soviet Union and instead with a pledge to merely increase defence spending by a modest amount, he came out looking foolish. MacArthur had spent the last decade as the face of American foreign policy in Asia, and had more experience in the region than just about anyone, while Stevenson’s greatest foreign policy accomplishment was a 1944 report on the state of the Italian economy. MacArthur had also reminded voters time and again that Red China had intervened in Korea and attacked American soldiers, while the Soviets had stayed out, making the Chinese seem like a greater threat to America’s security. Stevenson, MacArthur contended, just wanted to continue Truman’s policy, and wasn’t Truman’s policy what had brought about Korea in the first place?

***

MacArthur did not show any particular emotion upon hearing that Stevenson had been nominated. As far as he was concerned, winning the Republican nomination had just about put him in the White House, a view only reinforced by Stevenson’s weak showing on the campaign trail. His priority now was not worrying about the Democrats: they had already failed, but on finding the men that would make up his administration.

He had no shortage of loyal followers to choose from. Some, like Pat Echols, had come with him directly from Tokyo. Others, especially Phil LaFollette, would come from his campaign team. Most of what critics called the ‘Bataan gang’, including men who had been with him since the 1930s, had stayed back in Japan to assist Ridgway in the final stages of the occupation, and were now retiring from the Army to follow their hero in civilian life. Charles Willoughby had scored a CIA job. MacArthur’s ever-present legal pad, once used to give out orders in Japan, now contained a list of positions for advisors, cabinet members, and other important jobs. By the beginning of August, nearly every one of them had a name written next to it. Most of the names had been worshipping MacArthur for years.

Yet one position that would prove to be especially important in MacArthur’s presidency wasn’t even on the list. That position would be titled ‘Special Advisor to the President’.

The Special Advisor spot has its origins in an offer Harry Truman made to MacArthur and Stevenson in the middle of August 1952. Truman remembered well how poorly he had been prepared for the presidency. He had been vice president for less than three months, and had hardly known FDR, when he was expected to fill the great man’s shoes, and big shoes they had been. Remembering the difficulty of his own transition, Truman resolved to make it as easy as possible for his successor, even if his successor turned out to be His Majesty MacArthur. So he invited the two nominees to lunch with him at the White House, meet his cabinet and be briefed on matters foreign and domestic that would be of use to an incoming administration.

MacArthur noticed that even if this was a good-faith offer, which indeed it was, there would be strings attached. To be briefed implied that he needed briefing, an image that would not do. He was running to replace Truman’s foreign policy failures, not to embrace them. Any information he needed, he could get from Charles Willoughby. And by being photographed alongside Truman, wouldn’t that risk tying him to Truman’s pathetic legacy? So, much to Truman’s disappointment (if not his surprise), MacArthur declined the offer.

Frederick Ayer Jr had advised MacArthur to meet with Truman, but ever since Ned Almond had returned from Tokyo, MacArthur had stopped listening to his campaign manager whenever his former chief of staff offered a different opinion. Almond was just as terrible to deal with as his late uncle had said: whenever you wanted to see MacArthur, you had to go through Almond, and Almond didn’t let anyone through unless they were as much of a crony as he. Patton had outranked Almond, and had the guts to curse out the man until he got MacArthur’s ear directly (at least until MacArthur found a subordinate Patton was willing to deal with in Doyle Hickey), so he had been the one person able to get around the chief of staff. Without the protection of rank, that method wouldn’t work here.

Ayer knew that allowing the Bataan gang to dictate the flow of information to MacArthur would result in disaster eventually: their constant interference and incompetence had caused many setbacks on MacArthur’s battlefields. Furthermore, although MacArthur had effectively ruled Japan for six years, Ayer knew there were many differences between acting as a military governor and serving as the US President, and it did not help that, before this campaign, he had not been in the country for fifteen years. Even if MacArthur would not listen to Truman, he would be well served by an advisor who could prepare him for the job.

Ayer thought the best person would be Herbert Hoover. Hoover was a known MacArthur admirer, who had last year described the general as “a reincarnation of St. Paul into a great General of the Army who came out of the East”. Hoover had been President before, and knew the ins and outs of the office, so his advice could be supported by that experience. Most importantly, Hoover was one of the few people MacArthur looked up to. Most Americans would have placed Hoover as one of the worst Presidents, but MacArthur rated him as one of the top four. So Ayer wrote to Hoover asking if he would meet with MacArthur. Hoover agreed, and MacArthur was delighted by the news that Hoover was inviting him to lunch.

Hoover would not be the only late addition to the MacArthur team. The list on the general’s legal pad still had one important slot that remained frustratingly bare even as September dawned. MacArthur had spent days wondering, and had yet to come up with a suitable answer to the question: who would be his Secretary of Defence?

The need for civilians to control the military meant that any potential Secretary of Defence could not have served in the armed forces within the last ten years, precluding any Korean veterans and just about everyone from World War II, and indeed just about everyone from MacArthur’s inner circle. The Senate could grant an exception to this rule - they had for George Marshall - but as he was a general himself that wasn’t likely to happen. Senator Knowland, one of MacArthur’s strongest supporters and a man he had once considered as a potential running mate, happened to be a World War II veteran, ruling him out. Another vocal supporter, Kenneth Wherry, was perceived by MacArthur to be too isolationist, and wished to remain in the Senate besides. So MacArthur was forced to go on a weeks-long hunt.

He would find who he was looking for on a campaign tour of the Pacific Northwest.

MacArthur had long been impressed with the Air Force, having been a childhood friend of the pioneer Billy Mitchell (in whose court-martial MacArthur claimed to be the sole ‘not guilty’ vote). MacArthur had built his campaign in the Southwest Pacific around the capture of land-based airfields, and heaped praise upon his subordinate George Kenney when this proved successful. In Korea, the Air Force had sent the first Americans into combat in that war, and the strategic bombing of North Korea was so successful that it had to be called off for lack of targets less than a month after it began. The Air Force, MacArthur sensed, would be at the forefront of any future conflict, and therefore the front of the MacArthur defence policy, with the strategic bomber leading the way.

Nothing captured that vision better than the B-52. Still in an early testing phase of development, the B-52 looked promising: it could carry thirty tons of bombs, including an atomic weapon if need be, and it had the range to cover a continent and return without needing to refuel. He had been so impressed that he asked for a tour of the Boeing plant in Seattle, where he would meet the man behind the bomber.

William M. Allen was a man of big ideas. He had become President of Boeing in 1945, just as the war orders were drying up, and quickly pushed for the company to develop passenger aircraft alongside the heavy bombers it had become known for, and just months ago he had claimed to “bet the company” on the innovative 367-80 prototype that could one day become a jet-powered airliner. Boeing wasn’t quite a military company, but it came close, and Allen’s experience could be useful in Defence. Most importantly, he and MacArthur shared a great vision of the future of air power. By the end of the day, MacArthur had decided he wanted Allen on his team. Allen would take some convincing, but eventually agreed to serve as MacArthur’s Defence Secretary if confirmed by the Senate. The legal pad had its last spot filled.

***

November 5, 1952

Harry Truman folded the Chicago Daily Tribune and put the paper down on the Resolute Desk. Election Day had come and gone. Last time, the Tribune had printed arguably its most famous headline. He only wished that ‘AMERICA BACKS MAC’ was just as erroneous a line as Dewey defeating him had been. It wasn’t. It was never going to be. In 1948, his campaign had pulled off an upset by being energetic where Dewey’s was lacklustre. This time around, Stevenson had been the disappointment.

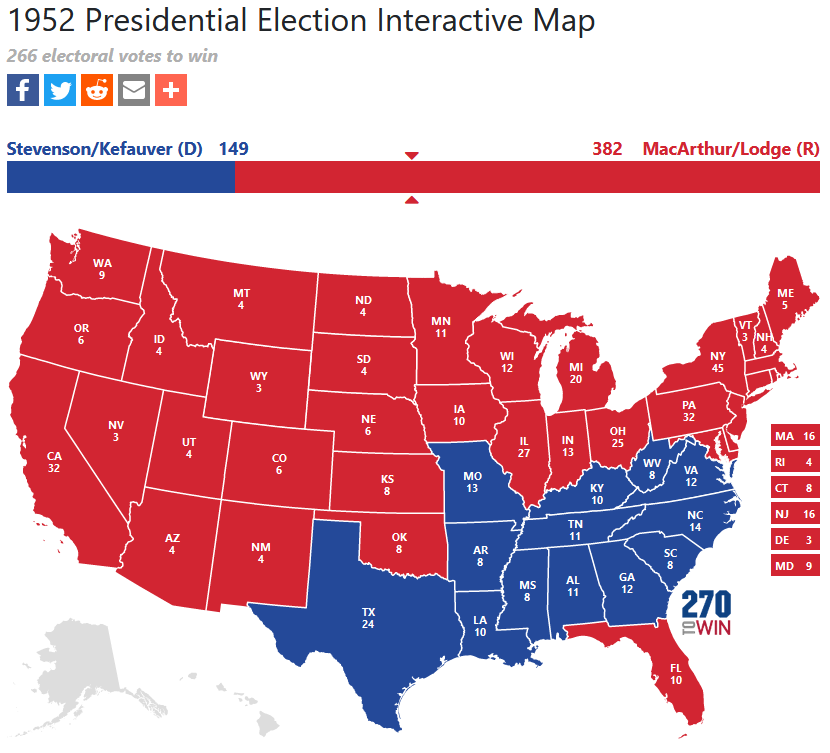

The results were the landslide everyone had predicted. The paper didn’t call any of the close races: those were still being counted, but none of them mattered any more. His Majesty had swept the Midwest, New England and California. When New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio were all called for MacArthur in the early hours of the morning, his victory was assured. The only question left was the margin, and with Stevenson hardly making an impression outside of the South, and even Florida proving surprisingly competitive, even that looked to be a great victory for the general who had caused the current president so much trouble.

So this is how my legacy comes to an end. Truman thought. God help us.

END OF PART IV

View attachment 638711

- BNC

Not as decisive a victory in the Electoral College as Eisenhower '52 but I could see MacArthur doing better in the popular vote as he avoided focusing any attention on the low voting rate South.

It's clear that one of if not the main problem of the MacArthur administration will be all those incompetent sychophants.

Air power is indeed the future but strategic bombing... isn't always the best strategic choice and is a rather ugly moral one.

2 questions. Is the next update going to be in about the usual amount of time or is the switching to Part 5 going to require a break. Also, could we get a list of MacArthur's cabinet?

It's clear that one of if not the main problem of the MacArthur administration will be all those incompetent sychophants.

Air power is indeed the future but strategic bombing... isn't always the best strategic choice and is a rather ugly moral one.

2 questions. Is the next update going to be in about the usual amount of time or is the switching to Part 5 going to require a break. Also, could we get a list of MacArthur's cabinet?

The real question is if any of Mac’s cronies are any good at their jobs. At best I think Mac ends up with a mixed legacy akin of Harding or Grant.

Guess it depends on how you're defining 'good'.I do wonder if having MacArthur in the White House will be a good thing for the Cold War.

Hadn't given too much thought to the popular vote as a whole, but I'd agree with this. A 57% win is certainly possible, let's go with thatNot as decisive a victory in the Electoral College as Eisenhower '52 but I could see MacArthur doing better in the popular vote as he avoided focusing any attention on the low voting rate South.

It's clear that one of if not the main problem of the MacArthur administration will be all those incompetent sychophants.

Good question. Unfortunately I'm not sure, my life has been a bit unpredictable as of late. I'd like to think I can keep doing weekly updates, but we'll see.Is the next update going to be in about the usual amount of time or is the switching to Part 5 going to require a break.

Was going to wait until chapter 33 for this, but why not?Also, could we get a list of MacArthur's cabinet?

President - Douglas MacArthur

Vice President - Henry Cabot Lodge

SecState - Henry Luce

SecTreasury - Phil LaFollette

SecDefence - William M. Allen

Attorney General - Richard Nixon

SecCommerce - Robert E. Wood

SecLabour - Courtney Whitney

Administrator of the Federal Security Agency* - Frederick Ayer Jr

Director of Bureau of the Budget - Joseph Dodge**

CIA - Charles Willoughby

FBI - J Edgar Hoover

UN Ambassador - Dwight Eisenhower

Chief of Staff - Ned Almond

Press Secretary - Pat Echols

Special Advisor*** - Herbert Hoover

Any spots not listed are presumed to be filled by 'generic' Republicans... they're not important to the story so I'm not going to list them.

JCS Chairman - George Stratemeyer

COS Army - Matthew Ridgway

COS Air Force - Earle E. Partridge

CNO - Arthur Struble

SAC - Curtis LeMay

* = This spot would be renamed Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare early in Ike's term IOTL. Feel like Mac would prefer the older name.

**= Ike's OTL pick. Happened to be Mac's financial advisor before he worked for Ike.

*** = ie. "Guy that the better members of Mac's team have recruited in the hopes he'll tell Mac not to do some stupid things"

I didn't realise Harding even had a mixed legacy. Thought everyone just agreed he was terrible and didn't do anything.The real question is if any of Mac’s cronies are any good at their jobs. At best I think Mac ends up with a mixed legacy akin of Harding or Grant.

As for Mac's cronies, you've got the list now, what do you think?

- BNC

Last edited:

The big 4 cabinet positions seem like a solid group though Nixon as Attorney General could go a lot ways. Willoughby and J Edgar together is not comforting.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: