Hunh! Learn something everyday. Thanks.Raoul de France was the Carolingian King from 923 to 936, same as OTL. Google google... OK, here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolph_of_France

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ethelred the Pious (Viking England)

- Thread starter False Dmitri

- Start date

The Tenth Century, Part 3: Cordoba and Compostela

As opportunities for ambitious Vikings continued to diminish in England, some sailed southwest and harassed the coasts of Spain. In 924, the chieftain Geirmund Roundhead captured Pamplona, a city weakened by a Muslim attack the year before.

Over the following years, attacks from England intensified even as the Muslim state of Al-Andalus gained in strength. In 929 its ruler Abd ar-Rahman, of the Umayyad family, proclaimed himself Caliph, renouncing all outside authority. He led his empire to cultural sophistication and territorial growth. His capital Cordoba became the largest city in the world during this period. Leon, the most important center of Christian resistance, fell in 942.

In 949 Olaf the Hairy, a cousin of Thorvald, the newly crowned king of the English kingdom of Jorvik, sailed with the greatest Viking force ever to attack Spain. He conquered what remained of the Kingdom of Galicia. He made his capital at Santiago de Compostela, a city holy to Christians. He acknowledged his cousin as overlord, but ruled Galisja* very independently.

Olaf actively encouraged Englanders to immigrate to Galisja. He was generous in granting jarldoms to loyal underlings. He failed in his bid to seize the throne of Jorvik (see a later post), but he defended his own kingdom against Moors and Vikings alike and passed his crown to his son Hrut.

Like many less powerful Anglo-Norse leaders in Spain, Hrut converted to the religion of his neighbors. While the Vikings in Pamplona and elsewhere adopted the dominant religion of Islam, Hrut became a devout Christian. Apparently after experiencing a vision, he restored Compostela's bishop and cut ties with England. Hoping to draw pilgrims to the holy city, he improved the port at Ferrol and the road connecting it to the capital. Soon his kingdom was known as Sant Jakob*, the Englesk form of "Santiago". Gradually, the kingdom's new ruling class grew more accultured to Spanish ways.

*All linguistic information in this post is provisional.

As opportunities for ambitious Vikings continued to diminish in England, some sailed southwest and harassed the coasts of Spain. In 924, the chieftain Geirmund Roundhead captured Pamplona, a city weakened by a Muslim attack the year before.

Over the following years, attacks from England intensified even as the Muslim state of Al-Andalus gained in strength. In 929 its ruler Abd ar-Rahman, of the Umayyad family, proclaimed himself Caliph, renouncing all outside authority. He led his empire to cultural sophistication and territorial growth. His capital Cordoba became the largest city in the world during this period. Leon, the most important center of Christian resistance, fell in 942.

In 949 Olaf the Hairy, a cousin of Thorvald, the newly crowned king of the English kingdom of Jorvik, sailed with the greatest Viking force ever to attack Spain. He conquered what remained of the Kingdom of Galicia. He made his capital at Santiago de Compostela, a city holy to Christians. He acknowledged his cousin as overlord, but ruled Galisja* very independently.

Olaf actively encouraged Englanders to immigrate to Galisja. He was generous in granting jarldoms to loyal underlings. He failed in his bid to seize the throne of Jorvik (see a later post), but he defended his own kingdom against Moors and Vikings alike and passed his crown to his son Hrut.

Like many less powerful Anglo-Norse leaders in Spain, Hrut converted to the religion of his neighbors. While the Vikings in Pamplona and elsewhere adopted the dominant religion of Islam, Hrut became a devout Christian. Apparently after experiencing a vision, he restored Compostela's bishop and cut ties with England. Hoping to draw pilgrims to the holy city, he improved the port at Ferrol and the road connecting it to the capital. Soon his kingdom was known as Sant Jakob*, the Englesk form of "Santiago". Gradually, the kingdom's new ruling class grew more accultured to Spanish ways.

*All linguistic information in this post is provisional.

Changing the name of the Galician capital would seem to entail significant population displacement; where are all these Vikings coming from?

England, mostly. Some are Nordicized Saxons. But there really aren't that many; the capital wasn't moved b/c of population displacement. Norse Galicia is smaller than Spanish Galicia - much of the land was absorbed into the Caliphate. Hrut and the gang set up their capital at Santiago de Compostela, which was more or less the center of the land they controlled.

[EDIT] Ah, you said changing the name, not the capital. For a generation or so, the new rulers kept an Anglo/Norse identity, but they gradually entered what remained of mainstream Spanish culture. Hrut married a Norse woman and their children all had Scandinavian names. That generation generally married Spanish nobility and gave Spanish names to their kids. Hrut's grandson became King Alfonso Sanchez of Castile (r. 1017-1036). Castile and Santiago/Sant Jakob were by then the only significant Christian states left in Spain.

Last edited:

Okay, here's where I know my ideas need help and comment from greater experts than myself.

Tenth Century, Part 4: A snapshot of England in 930

Overview:

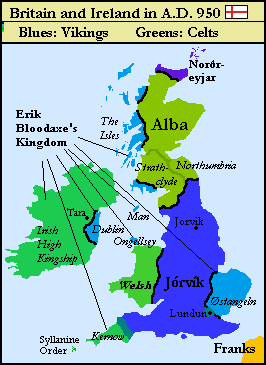

It is approximately 50 years after the Danes and Norse consluded their conquest of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (except northern Northumbria, which is under the suzerainty of Alba). Norse England remains divided into two kingdoms, Jorvik (York) and Ostangeln (Eastanglia). Both kingdoms had been established before the conquest of the 870s, but both came to be dominated by the leaders of the "Great Heathen Army."

Politics:

The leaders of the conquest formed a new class of nobility. Members of this new class dominate the government of both kingdoms and have maintained the power to choose the kings. Here as in mainland Scandinavia, becoming king is an act of personal power that requires a large number of heavily armed supporters, an act that can be undone with the appearance of a rival with more supporters or heavier arms.

At this moment, neither kingdom is ruled by a direct descendant of Halfdan or Ivar, the brothers who led the Great Army. However, their families have grown into large and powerful houses that weild great influence in both kingdoms. Halfdan's granddaughter Raghild is married to Eirik, the king of Eastanglia.

Land patterns:

In Ostangeln, the region that attracted the greatest density of Scandinavian immigrants, the village system predominates in agriculture. The largest class of society consists of free peasants of Scandinavian extraction. Much of the land is communally controlled, but most peasants also have individual plots.

Jorvik's settlement patterns follow a continuum from north to south. In the northern core lands of the kingdom, the mainly Norse population lives in villages with fields clustered around.

In Mercia, the former "Five Boroughs" region, small landholdings predominate. This region was parceled out to Viking warriors following the conquest of England, and later arrivals were also able to obtain farms. The population is divided into a Norse nobility, a class of free Dano-Norse peasant farmers, and a class of Anglo-Saxon tenants.

Southern Jorvik is the least "Nordified". A Danish/Norwegian nobility was simply superimposed on the existing Saxon system, with several shires and earldoms continuing intact from the previous era. This was the region of the "English Law" established in the late 800s. The preservation of Saxon laws and administration prevented large-scale commandeering of the land by Vikings.

Being the magnate over a territory has not yet been equated with owning a territory. As feudal ideas ceep in from France, the magnates of the south will begin to demand more direct rule of their territories.

One recent social change that has been noted by the landowning classes (magnates and free peasants) is the absence of free land. Viking England in the years after 976 acquired a culture of upward mobility and opportunism made possible by the continued seizure of Saxon estates. As society becomes more stable, many young men are looking elsewhere for personal fortune.

Religion:

The English Church was impoverished by the conquest, with most of its treasures taken and looted. Many of the artifacts of Anglo-Saxon Christianity were smuggled abroad, to unconquered parts of Wales, Scotland, or Ireland. Many monks and priests similarly fled the country. Those that remained had to make do with bare buildings and meager possessions. Several bishoprics have not been restored, but archbishops continue to sit at their ancient seats in Canterbury and York, the latter of which is also a royal capital.

The indiginous Saxons have not discarded their faith, but monks and priests have actively sought to convert their conquerors, with varying success. Already the distinction is blurring between Saxon Christians who speak Norse, and Scandinavians who have converted to Christianity. With such a fertile mission field at home, English missionaries no longer travel to mainland Scandinavia - slowing the spread of the Faith there. However, this is offset somewhat by converted English Vikings moving back to Denmark or Norway.

Paganism remains the religion of the majority of Dano-Norse of all classes. Predicatably, those that have more daily contact with Saxons, such as those in the South or far North, are converting in greater numbers. The family of the Jarl of Kent are all believers and have become key patrons of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Tenth Century, Part 4: A snapshot of England in 930

Overview:

It is approximately 50 years after the Danes and Norse consluded their conquest of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (except northern Northumbria, which is under the suzerainty of Alba). Norse England remains divided into two kingdoms, Jorvik (York) and Ostangeln (Eastanglia). Both kingdoms had been established before the conquest of the 870s, but both came to be dominated by the leaders of the "Great Heathen Army."

Politics:

The leaders of the conquest formed a new class of nobility. Members of this new class dominate the government of both kingdoms and have maintained the power to choose the kings. Here as in mainland Scandinavia, becoming king is an act of personal power that requires a large number of heavily armed supporters, an act that can be undone with the appearance of a rival with more supporters or heavier arms.

At this moment, neither kingdom is ruled by a direct descendant of Halfdan or Ivar, the brothers who led the Great Army. However, their families have grown into large and powerful houses that weild great influence in both kingdoms. Halfdan's granddaughter Raghild is married to Eirik, the king of Eastanglia.

Land patterns:

In Ostangeln, the region that attracted the greatest density of Scandinavian immigrants, the village system predominates in agriculture. The largest class of society consists of free peasants of Scandinavian extraction. Much of the land is communally controlled, but most peasants also have individual plots.

Jorvik's settlement patterns follow a continuum from north to south. In the northern core lands of the kingdom, the mainly Norse population lives in villages with fields clustered around.

In Mercia, the former "Five Boroughs" region, small landholdings predominate. This region was parceled out to Viking warriors following the conquest of England, and later arrivals were also able to obtain farms. The population is divided into a Norse nobility, a class of free Dano-Norse peasant farmers, and a class of Anglo-Saxon tenants.

Southern Jorvik is the least "Nordified". A Danish/Norwegian nobility was simply superimposed on the existing Saxon system, with several shires and earldoms continuing intact from the previous era. This was the region of the "English Law" established in the late 800s. The preservation of Saxon laws and administration prevented large-scale commandeering of the land by Vikings.

Being the magnate over a territory has not yet been equated with owning a territory. As feudal ideas ceep in from France, the magnates of the south will begin to demand more direct rule of their territories.

One recent social change that has been noted by the landowning classes (magnates and free peasants) is the absence of free land. Viking England in the years after 976 acquired a culture of upward mobility and opportunism made possible by the continued seizure of Saxon estates. As society becomes more stable, many young men are looking elsewhere for personal fortune.

Religion:

The English Church was impoverished by the conquest, with most of its treasures taken and looted. Many of the artifacts of Anglo-Saxon Christianity were smuggled abroad, to unconquered parts of Wales, Scotland, or Ireland. Many monks and priests similarly fled the country. Those that remained had to make do with bare buildings and meager possessions. Several bishoprics have not been restored, but archbishops continue to sit at their ancient seats in Canterbury and York, the latter of which is also a royal capital.

The indiginous Saxons have not discarded their faith, but monks and priests have actively sought to convert their conquerors, with varying success. Already the distinction is blurring between Saxon Christians who speak Norse, and Scandinavians who have converted to Christianity. With such a fertile mission field at home, English missionaries no longer travel to mainland Scandinavia - slowing the spread of the Faith there. However, this is offset somewhat by converted English Vikings moving back to Denmark or Norway.

Paganism remains the religion of the majority of Dano-Norse of all classes. Predicatably, those that have more daily contact with Saxons, such as those in the South or far North, are converting in greater numbers. The family of the Jarl of Kent are all believers and have become key patrons of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Last edited:

The Tenth Century, Part 5: Conquests of the Bloodaxe Family

Erik Bloodaxe was a much-feared Viking leader. A great king, he had obtained the submission of all other kings of Norway in the early 930s. In 935, however, his brother Haakon returned to the country. Haakon had been raised in the Jorvikish court and spent his youth fighting in Ireland and Spain. With the support of the Norwegian kings and nobles, Haakon overthrew his brother.

Erik fled to England. When he arrived in Eastanglia he lost no time in planning another conquest. He amassed an army of followers and sailed to the Orkney Islands to amass more. The fleet attacked Dublin, at that time a jarldom loyal to King Beorn of Jorvik. Erik's conquest was swift. He not only established himself as the independent King of Dublin, but within three years had emerged as Ireland's dominant ruler.

Erik and his son, the powerful warrior Harald Greycloak, fought ceaselessly against the surrounding Irish statelets, forcing their neighbors to acknowledge Erik's supremacy on the island. The Gaelic lords proclaimed him High King at the ancient gathering place of Tara in 938. While this was a purely symbolic post, it was a sure sign that Erik was the new power on the island. Harald's prowess in battle and the presence of his influetial mother, Erik's wife Gunnhild, seemed to make Harald's position as Erik's heir quite secure.

However, Erik had an illegitimate son, also named Erik, whom he also favored. In 946, the elder Erik supplied his son with ships and men to make his own name, common for landless illegitimate sons. The younger Erik embarked on an incredible voyage of conquest from Dublin to Eastanglia. Along the way he attacked and defeated the Norse kingdoms of Man and Anglesey, as well as the western part of Cornwall. Erik secured the submission of all the peoples he attacked, and his voyage was later immortalized in a number of sagas. By 947 he was sub-king of Eastanglia; he continued to acknowledge his father in Dublin as king over him. The younger Erik's victories earned him the epithet "the Mariner" and positioned him as a dangerous rival to his half-brother Harald.

His position gained by conquest, Erik the Mariner took the traditional next step and secured it farther through marriage. He reached out to his new neighbor, King Thorvald of Jorvik. His daughter Halla was married to Thorvald's nephew Thorkell in 953.

The next year, Thorvald died unexpectedly. Erik the Mariner hoped to put his son-in-law on the throne and thus increase his influence over Jorvik. Thorkell faced a challenge, however, from his uncle, Olaf the Hairy, then King of Galicia in Spain. Both Eriks lent their full support to Thorkell. In a battle near London, Thorkell and the Eriks defeated Olaf. Olaf went back to Spain, and Thorkell became King.

Harald, meanwhile, gained strength in Ireland. In 952 he fortified the hill at Tara, hoping to make his father's symbolic High Kingship a permanent institution. By 960 or so he (with his mother) was governing Dublin for his aging father.

Erik Bloodaxe finally died in 964, having led a surprisingly long life for so warlike a king. Erik the Mariner immediately began to vie with his half-brother, Harald Greycloak, for control of Dublin, Man, and Ostangeln.

Erik Bloodaxe finally died in 964. The skalds all agreed that a man so steeped in war hardly deserved to live so long. Harald Greycloak immediately claimed the kingship, supported by all the thanes of his Irish lands.

Erik Bloodaxe was a much-feared Viking leader. A great king, he had obtained the submission of all other kings of Norway in the early 930s. In 935, however, his brother Haakon returned to the country. Haakon had been raised in the Jorvikish court and spent his youth fighting in Ireland and Spain. With the support of the Norwegian kings and nobles, Haakon overthrew his brother.

Erik fled to England. When he arrived in Eastanglia he lost no time in planning another conquest. He amassed an army of followers and sailed to the Orkney Islands to amass more. The fleet attacked Dublin, at that time a jarldom loyal to King Beorn of Jorvik. Erik's conquest was swift. He not only established himself as the independent King of Dublin, but within three years had emerged as Ireland's dominant ruler.

Erik and his son, the powerful warrior Harald Greycloak, fought ceaselessly against the surrounding Irish statelets, forcing their neighbors to acknowledge Erik's supremacy on the island. The Gaelic lords proclaimed him High King at the ancient gathering place of Tara in 938. While this was a purely symbolic post, it was a sure sign that Erik was the new power on the island. Harald's prowess in battle and the presence of his influetial mother, Erik's wife Gunnhild, seemed to make Harald's position as Erik's heir quite secure.

However, Erik had an illegitimate son, also named Erik, whom he also favored. In 946, the elder Erik supplied his son with ships and men to make his own name, common for landless illegitimate sons. The younger Erik embarked on an incredible voyage of conquest from Dublin to Eastanglia. Along the way he attacked and defeated the Norse kingdoms of Man and Anglesey, as well as the western part of Cornwall. Erik secured the submission of all the peoples he attacked, and his voyage was later immortalized in a number of sagas. By 947 he was sub-king of Eastanglia; he continued to acknowledge his father in Dublin as king over him. The younger Erik's victories earned him the epithet "the Mariner" and positioned him as a dangerous rival to his half-brother Harald.

His position gained by conquest, Erik the Mariner took the traditional next step and secured it farther through marriage. He reached out to his new neighbor, King Thorvald of Jorvik. His daughter Halla was married to Thorvald's nephew Thorkell in 953.

The next year, Thorvald died unexpectedly. Erik the Mariner hoped to put his son-in-law on the throne and thus increase his influence over Jorvik. Thorkell faced a challenge, however, from his uncle, Olaf the Hairy, then King of Galicia in Spain. Both Eriks lent their full support to Thorkell. In a battle near London, Thorkell and the Eriks defeated Olaf. Olaf went back to Spain, and Thorkell became King.

Harald, meanwhile, gained strength in Ireland. In 952 he fortified the hill at Tara, hoping to make his father's symbolic High Kingship a permanent institution. By 960 or so he (with his mother) was governing Dublin for his aging father.

Erik Bloodaxe finally died in 964, having led a surprisingly long life for so warlike a king. Erik the Mariner immediately began to vie with his half-brother, Harald Greycloak, for control of Dublin, Man, and Ostangeln.

Erik Bloodaxe finally died in 964. The skalds all agreed that a man so steeped in war hardly deserved to live so long. Harald Greycloak immediately claimed the kingship, supported by all the thanes of his Irish lands.

Hm, still not much of a response. Well, here goes the next step.

The Ninth Century, Part 6: The Bloodaxe War

1. The axe is sharpened

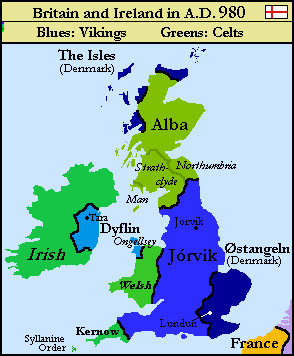

After Erik Bloodaxe died in 964, his son Harald Greycloak claimed sovereignty the entire kingdom - both the Irish lands that he himself ruled, and the islands to the west plus Eastanglia, ruled by his half-brother, Erik the Mariner. But Erik refused to submit to Harald as he had to their father. In response to this act of insolence, Harald prepared for war.

But Erik the Mariner was too sure of himself. His western lands - Ongelsey, Man, and the Hebrides - were vulnerable to attack from Dyflin and difficult to defend from his base in Östangeln. Harald attacked the islands and quickly secured the submission of their sub-kings. Erik turned to his son-in-law Thorkell of Jorvik (York) for aid, while Harald's mother Gunnhild appealed to allies in Orkney and in distant Denmark. All the islands prepared for a wide-spanning war.

2. The axe swings

Gunnhild traveled to Orkney, where Thorfinn Skullsplitter ruled as Jarl with his brother Arnkel. She promised to restore their former rule over some of the Hebrides in exchange for joining the war against Erik. A fleet from Orkney sailed against Östangeln in 965.

But Erik was not called the Mariner for nothing. Sailing out to meet Thorfinn, he sank the greater part of the Orkneyish fleet and forced the Skullsplitter to retreat. In days Erik outfitted a retaliatory expedition and sailed north to Orkney, hoping to obtain the quick surrender of his half-brother's ally. Erik failed to force a landing in the isles and fell back to the shore of Katanes (Caithness) on the mainland, where he and his men wintered.

In the spring of 966, Arnkel attacked Erik's positions in Katanes and was defeated. Erik had won, but his position was not strong enough to demand Orkney's outright submission to him. He settled for a promise of neutrality in the war and the establishment of his rule in those parts of the northern Hebrides that Harald had returned to Orkney.

Satisfied, Erik returned to Östangeln. He met with his son-in-law Thorkell of Jorvik, and they discussed the possibility of invading Ireland and dividing up Harald's conquests. Thorkell owed his position to Erik and saw in this new war the chance to make a name for himself, especially after his failed attempt to conquer Galicia, Spain, from his cousin in 964. He invaded the Isle of Man in 967 while Erik sailed - for the second time - against Cornwall, ruled by Sub-king Donyarth in vassalage to Harald. The Cornish were used to the ritual of surrender and homage to whatever Viking warlord happened to be sailing through, so by 968 Erik was using Kernow as a base to attack his brother's lands in Ireland.

3. The axe falls

The Skullsplitter had been no help at all, so Harald and Gunnhild looked elsewhere for an ally. They appealed to Dub, King of Scots. The Scottish Kingdom of Alba was probably the most powerful state in the British Isles. Celtic and Christian, Alba had been able to weather the Viking attacks that had brought down the rest of the archipelago, and since 900 the Scots and Vikings had been content to largely ignore one another. But in 967, Dub had an interest in helping Harald defeat Erik. Harald promised Dub all the islands off his coast should they win - Man, the Hebrides, even the Orkneys. Dub began constructing a fleet to attack the Hebrides and Man.

The Christian fleet took two years to complete. During that time, both Erik and Thorkell tried repeatedly to seize Dyflin and end the war. They failed every time. Erik was equally unsuccessful diplomatically: he was unable to find any powerful Irish chieftans, Celt or Norse, willing to turn against Harald. When it became clear that the Scots were preparing for war, Thorkell became a much less willing ally. He left his base on Man and returned to tend to his northern borderlands, gearing up for a Scottish invasion.

The Gaelic storm hit in the middle of 969. Dub and his fleet sailed to the Hebrides and then to Man, burning the Viking ships moored there. Although inexperienced in seafaring, their overwhelming numbers were too much for Erik's small but seasoned forces. Dub sailed home in triumph with plans to invade Jórvik itself in the coming months.

However, Scotland did not rest during Dub's absense. His succession to the throne had always been disputed by a number of relatives. Dub returned to find his cousin Cuilen securely on the throne with all the nobles supporting him. Cuilen had his cousin placed under arrest and later beheaded.

Cuilen thought Dub a fool for provoking the Jórvikish kingdom, a move he felt would lead to endless war with few lasting gains. He met with Thorkell in a field near their border and agreed to switch sides. Far better that the three kingdoms of Great Britain (Alba, Jórvik, and Östangeln) should band together and conquer the upstart in Ireland, Harald. Early in 970, three armies, led by Erik, Thorkell, and Cuilen, landed in Ireland. Harald Greycloak appeared to be out of luck.

4. The axe is bloodied.

There was one option left for the heir of Bloodaxe. Gunnhild was descended (or claimed to be) from the long-dead king of Denmark, Gorm the Old. She would now appeal to her distant cousin, Denmark's current King, Harald Bluetooth. She begged him to come to her aid, offering all sorts of honors and lands should he agree. He did. Gunnhild sailed into Dyflin at the head of a vast fleet of ships lent by the king.

After driving the invaders off of Ireland, Harald Greycloak decided to go after his brother's base in Östangeln. With Danish help, he was able to secure a number of towns and fortresses there. In 972, Harald Bluetooth himself arrived from Denmark with additional troops. His gamble seemed to be paying off, and he stood to seize a fine prize in England.

By 973, the Haralds had conquered Östangeln and driven Erik off the island. Harald Greycloak swore the requisite oaths of loyalty to Harald Bluetooth of Denmark. Harald B now had a foothold in England. He pressed on to the important trading city of Lundun, for decades considered "shared" between Jorvik and Östangeln. His forces took it after a long seige. To stem the tide, Thorkell met with the Haralds in December. In return for peace, he paid a hefty ransom to the victors. Harald Bluetooth received not only Lundun, but Essex and Kent as well. The growth of the Danish Empire had begun.

Cuilen, a cautious ruler, did not like the prospect of facing Dyflin and Denmark alone. He returned home, bringing with him all his forces. In the end, the Scots gained only Man and the southernmost Hebrides, which had been conquered by his late cousin Dub back in 969.

5. The axe is shouldered

The Haralds persued Erik to his refuge in the Orkneys, which he fled in 974. A compulsive wanderer, he went to the Faeroes and later Iceland, where he died c. 980.

Harald Greycloak was secure in his Irish kingdom that he had helped conquer and enlarge in his youth. He also bore the title Sub-King of Östangeln, although there he was not free to act without permission from Erik Bluetooth in Denmark.

Although the war had begun as a succession crisis between two pagan Vikings in England and Ireland, the real winner turned out to be Christian(izing) Denmark. Harald Bluetooth gained two new territories in the British archipelago, Orkney and Östangeln, both of which contained more territory than they had a decade earlier. Harald set the stage for great conquests in England by his successors, Sweyn and Cnut.

The Celtic states of Britain came through the war shaken but intact. Scotland had in fact gained territory, while Cornwall managed, once again, to slip through the cracks of power and hang on to its independence, if only for a little while.

The other winners of the war were the skalds and their audiences, who for centuries thereafter would be entertained and amazed by the sagas written about it. The Saga of Erik the Mariner is considered the finest example of Ongellseyan poetry, and many other fine epics emerged from Ireland, England, Man, and Orkney. Erik's reputation traveled with him to Iceland and later to Greenland, where even more fantastical accounts of the long war were composed and later written down.

The Ninth Century, Part 6: The Bloodaxe War

1. The axe is sharpened

After Erik Bloodaxe died in 964, his son Harald Greycloak claimed sovereignty the entire kingdom - both the Irish lands that he himself ruled, and the islands to the west plus Eastanglia, ruled by his half-brother, Erik the Mariner. But Erik refused to submit to Harald as he had to their father. In response to this act of insolence, Harald prepared for war.

But Erik the Mariner was too sure of himself. His western lands - Ongelsey, Man, and the Hebrides - were vulnerable to attack from Dyflin and difficult to defend from his base in Östangeln. Harald attacked the islands and quickly secured the submission of their sub-kings. Erik turned to his son-in-law Thorkell of Jorvik (York) for aid, while Harald's mother Gunnhild appealed to allies in Orkney and in distant Denmark. All the islands prepared for a wide-spanning war.

2. The axe swings

Gunnhild traveled to Orkney, where Thorfinn Skullsplitter ruled as Jarl with his brother Arnkel. She promised to restore their former rule over some of the Hebrides in exchange for joining the war against Erik. A fleet from Orkney sailed against Östangeln in 965.

But Erik was not called the Mariner for nothing. Sailing out to meet Thorfinn, he sank the greater part of the Orkneyish fleet and forced the Skullsplitter to retreat. In days Erik outfitted a retaliatory expedition and sailed north to Orkney, hoping to obtain the quick surrender of his half-brother's ally. Erik failed to force a landing in the isles and fell back to the shore of Katanes (Caithness) on the mainland, where he and his men wintered.

In the spring of 966, Arnkel attacked Erik's positions in Katanes and was defeated. Erik had won, but his position was not strong enough to demand Orkney's outright submission to him. He settled for a promise of neutrality in the war and the establishment of his rule in those parts of the northern Hebrides that Harald had returned to Orkney.

Satisfied, Erik returned to Östangeln. He met with his son-in-law Thorkell of Jorvik, and they discussed the possibility of invading Ireland and dividing up Harald's conquests. Thorkell owed his position to Erik and saw in this new war the chance to make a name for himself, especially after his failed attempt to conquer Galicia, Spain, from his cousin in 964. He invaded the Isle of Man in 967 while Erik sailed - for the second time - against Cornwall, ruled by Sub-king Donyarth in vassalage to Harald. The Cornish were used to the ritual of surrender and homage to whatever Viking warlord happened to be sailing through, so by 968 Erik was using Kernow as a base to attack his brother's lands in Ireland.

3. The axe falls

The Skullsplitter had been no help at all, so Harald and Gunnhild looked elsewhere for an ally. They appealed to Dub, King of Scots. The Scottish Kingdom of Alba was probably the most powerful state in the British Isles. Celtic and Christian, Alba had been able to weather the Viking attacks that had brought down the rest of the archipelago, and since 900 the Scots and Vikings had been content to largely ignore one another. But in 967, Dub had an interest in helping Harald defeat Erik. Harald promised Dub all the islands off his coast should they win - Man, the Hebrides, even the Orkneys. Dub began constructing a fleet to attack the Hebrides and Man.

The Christian fleet took two years to complete. During that time, both Erik and Thorkell tried repeatedly to seize Dyflin and end the war. They failed every time. Erik was equally unsuccessful diplomatically: he was unable to find any powerful Irish chieftans, Celt or Norse, willing to turn against Harald. When it became clear that the Scots were preparing for war, Thorkell became a much less willing ally. He left his base on Man and returned to tend to his northern borderlands, gearing up for a Scottish invasion.

The Gaelic storm hit in the middle of 969. Dub and his fleet sailed to the Hebrides and then to Man, burning the Viking ships moored there. Although inexperienced in seafaring, their overwhelming numbers were too much for Erik's small but seasoned forces. Dub sailed home in triumph with plans to invade Jórvik itself in the coming months.

However, Scotland did not rest during Dub's absense. His succession to the throne had always been disputed by a number of relatives. Dub returned to find his cousin Cuilen securely on the throne with all the nobles supporting him. Cuilen had his cousin placed under arrest and later beheaded.

Cuilen thought Dub a fool for provoking the Jórvikish kingdom, a move he felt would lead to endless war with few lasting gains. He met with Thorkell in a field near their border and agreed to switch sides. Far better that the three kingdoms of Great Britain (Alba, Jórvik, and Östangeln) should band together and conquer the upstart in Ireland, Harald. Early in 970, three armies, led by Erik, Thorkell, and Cuilen, landed in Ireland. Harald Greycloak appeared to be out of luck.

4. The axe is bloodied.

There was one option left for the heir of Bloodaxe. Gunnhild was descended (or claimed to be) from the long-dead king of Denmark, Gorm the Old. She would now appeal to her distant cousin, Denmark's current King, Harald Bluetooth. She begged him to come to her aid, offering all sorts of honors and lands should he agree. He did. Gunnhild sailed into Dyflin at the head of a vast fleet of ships lent by the king.

After driving the invaders off of Ireland, Harald Greycloak decided to go after his brother's base in Östangeln. With Danish help, he was able to secure a number of towns and fortresses there. In 972, Harald Bluetooth himself arrived from Denmark with additional troops. His gamble seemed to be paying off, and he stood to seize a fine prize in England.

By 973, the Haralds had conquered Östangeln and driven Erik off the island. Harald Greycloak swore the requisite oaths of loyalty to Harald Bluetooth of Denmark. Harald B now had a foothold in England. He pressed on to the important trading city of Lundun, for decades considered "shared" between Jorvik and Östangeln. His forces took it after a long seige. To stem the tide, Thorkell met with the Haralds in December. In return for peace, he paid a hefty ransom to the victors. Harald Bluetooth received not only Lundun, but Essex and Kent as well. The growth of the Danish Empire had begun.

Cuilen, a cautious ruler, did not like the prospect of facing Dyflin and Denmark alone. He returned home, bringing with him all his forces. In the end, the Scots gained only Man and the southernmost Hebrides, which had been conquered by his late cousin Dub back in 969.

5. The axe is shouldered

The Haralds persued Erik to his refuge in the Orkneys, which he fled in 974. A compulsive wanderer, he went to the Faeroes and later Iceland, where he died c. 980.

Harald Greycloak was secure in his Irish kingdom that he had helped conquer and enlarge in his youth. He also bore the title Sub-King of Östangeln, although there he was not free to act without permission from Erik Bluetooth in Denmark.

Although the war had begun as a succession crisis between two pagan Vikings in England and Ireland, the real winner turned out to be Christian(izing) Denmark. Harald Bluetooth gained two new territories in the British archipelago, Orkney and Östangeln, both of which contained more territory than they had a decade earlier. Harald set the stage for great conquests in England by his successors, Sweyn and Cnut.

The Celtic states of Britain came through the war shaken but intact. Scotland had in fact gained territory, while Cornwall managed, once again, to slip through the cracks of power and hang on to its independence, if only for a little while.

The other winners of the war were the skalds and their audiences, who for centuries thereafter would be entertained and amazed by the sagas written about it. The Saga of Erik the Mariner is considered the finest example of Ongellseyan poetry, and many other fine epics emerged from Ireland, England, Man, and Orkney. Erik's reputation traveled with him to Iceland and later to Greenland, where even more fantastical accounts of the long war were composed and later written down.

Still very little interest in this one.  I hope that's because it's an obscure era and not because the TL is utterly hopeless.

I hope that's because it's an obscure era and not because the TL is utterly hopeless.

The Ninth Century, Part 7: The Caliph's Triumph

After the city of Leon fell to the Caliph and Galicia was overrun by the English(1), Castile emerged as the strongest Christian state in Spain. Count Ferdinand Gonzalez(2) united his armies with Asturias to fend off Abd ar-Rahman's invasion in 950 at the Battle of Lena. The soldiers named him king of Castile and Asturias, and Ferdinand led his kingdom to successfully resist conquest.

Abd ar-Rahman's successor al-Hakam did not enjoy the same success. He attacked the Anglo-Viking kingdom of Galisja; the time seemed right because Galisja was caught up in squabbles of its own. Thorkell of Jorvik had invaded in 963 and sacked the holy shrine at Santiago de Compostela. Thorkell was driven away, but he took much of the wealth of the kingdom with him. Even so, the Galisjans were able to rally to halt al-Hakam when he invaded in 966.

The year 976 saw a new power emerge in Cordoba: the caliph's vizier, Al-Mansur. Al-Mansur was nominally the mere adviser to the real caliph, Hisham. But he was the true power behind the throne, and he led Andalusia in a new phase of expansion at the expense of the Spanish Christians. He pushed into the Pyrennes in the 970s and built a new city to be the center of Andalusian power in the northeast: Al-Darra. He sacked Barcelona a few years later.

What al-Mansur could not conquer, he was content to control. In the 990s he supported Sancho, rebellious son of King Garcia of Castile. Sancho drove his father out of Burgos, confining him to his lands in Asturias. Garcia died soon afterward, leaving Sancho free to take over the entire kingdom. Upon doing so, however, he attempted to break free of al-Mansur's control. Al-Mansur attacked Burgos directly, and in 997 he again secured Sancho's loyalty as a Cordoban vassal. By the year 1000, al-Mansur was at the height of his power. All the land of Iberia had either been conquered or forced to submit to his overlordship. The Umayyad Caliphate seemed invincible - something that was to be disproved early in the following century.

(1) Or, more accurately, divided between the Cordoban Caliphate and English Viking raiders.

(2) The Castilian line remains basically as OTL until the late part of the century.

The Ninth Century, Part 7: The Caliph's Triumph

After the city of Leon fell to the Caliph and Galicia was overrun by the English(1), Castile emerged as the strongest Christian state in Spain. Count Ferdinand Gonzalez(2) united his armies with Asturias to fend off Abd ar-Rahman's invasion in 950 at the Battle of Lena. The soldiers named him king of Castile and Asturias, and Ferdinand led his kingdom to successfully resist conquest.

Abd ar-Rahman's successor al-Hakam did not enjoy the same success. He attacked the Anglo-Viking kingdom of Galisja; the time seemed right because Galisja was caught up in squabbles of its own. Thorkell of Jorvik had invaded in 963 and sacked the holy shrine at Santiago de Compostela. Thorkell was driven away, but he took much of the wealth of the kingdom with him. Even so, the Galisjans were able to rally to halt al-Hakam when he invaded in 966.

The year 976 saw a new power emerge in Cordoba: the caliph's vizier, Al-Mansur. Al-Mansur was nominally the mere adviser to the real caliph, Hisham. But he was the true power behind the throne, and he led Andalusia in a new phase of expansion at the expense of the Spanish Christians. He pushed into the Pyrennes in the 970s and built a new city to be the center of Andalusian power in the northeast: Al-Darra. He sacked Barcelona a few years later.

What al-Mansur could not conquer, he was content to control. In the 990s he supported Sancho, rebellious son of King Garcia of Castile. Sancho drove his father out of Burgos, confining him to his lands in Asturias. Garcia died soon afterward, leaving Sancho free to take over the entire kingdom. Upon doing so, however, he attempted to break free of al-Mansur's control. Al-Mansur attacked Burgos directly, and in 997 he again secured Sancho's loyalty as a Cordoban vassal. By the year 1000, al-Mansur was at the height of his power. All the land of Iberia had either been conquered or forced to submit to his overlordship. The Umayyad Caliphate seemed invincible - something that was to be disproved early in the following century.

(1) Or, more accurately, divided between the Cordoban Caliphate and English Viking raiders.

(2) The Castilian line remains basically as OTL until the late part of the century.

I read this timeline back when it was only on the AH wikia wiki.

And I must say, it is very well-done and original. I like the idea of a Norse England, which has been discussed before on the forum but AFAIK no timeline has been done.

By the way, is this posted verbatim from the AH wikia? Or have you made any major changes before posting here?

And I must say, it is very well-done and original. I like the idea of a Norse England, which has been discussed before on the forum but AFAIK no timeline has been done.

By the way, is this posted verbatim from the AH wikia? Or have you made any major changes before posting here?

Thanks.

So far this has been nearly copy-pasted from the AH Wikia. I've made some modifications and ironed out some inconsistencies. I brought it here mostly because this site has more members, more discussion, and (hate to say it) more intelligent commentary than the Wikia, where the structure is good for joint projects but less useful as a forum.

The biggest changes to come out of this discussion relate to Iceland and America and Russia, which have not really been touched on yet.

So far this has been nearly copy-pasted from the AH Wikia. I've made some modifications and ironed out some inconsistencies. I brought it here mostly because this site has more members, more discussion, and (hate to say it) more intelligent commentary than the Wikia, where the structure is good for joint projects but less useful as a forum.

The biggest changes to come out of this discussion relate to Iceland and America and Russia, which have not really been touched on yet.

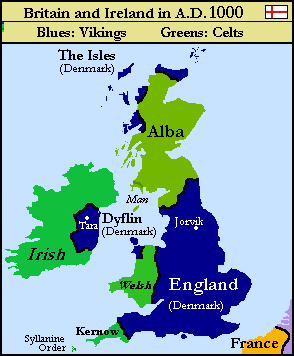

The Ninth Century, Part 8: The Second Danish Invasion

Sweyn Forkbeard

Sweyn Forkbeard became King of Denmark in 986 after his father's death. Though a baptized Christian, Sweyn saw faith as a very fluid thing. He did not allow his newfound salvation to temper either his ruthlessness or his practice of the religion of his ancestors. He would readily turn to both Odin and Jesus when it suited his purpose. He could behave as a pagan among pagans and a Christian among Christians. He was an ally of the religious leaders of both faiths in his realms in Denmark, England, and Ireland.

Thanks to his father's conquests in the Bloodaxe War, Sweyn's realm included the Kingdom of Östangeln in England, ruled by King Erik of Dyflin [Dublin] as a vassalage. It also included the Jarldom of Orkney and the Isles to the north of Britain.

Invasion of England

After securing his position as king with the usual round of wars and assassinations, Sweyn embarked on a campaign to expand his empire in 994. He sailed to his land in Östangeln with a large fleet. With the ships, he began attacking the eastern coasts of the kingdom of Jórvik.

In 995, Sweyn marched an army into the English Midlands. There were victories and setbacks, but word of Sweyn's ruthlessness spread throughout the country. When he campaigned in the south of England the following year, most of the Scandinavian nobility joined his side willingly. But the South was still a largely Anglo-Saxon region in which shire officials competed for influence with the feudal lords. Some of the villages sought to resist Sweyn and were virtually destroyed.

In 997, Sweyn's advance took him up along Jorvik's northeastern coast. Erik of Dyflin saw that Sweyn's conquest of the kingdom could spell the end of his own independence. He joined with Hrolf of Jorvik to fight against his erstwhile overlord. In 998, Sweyn defeated Hrolf and Erik and captured the city of Jórvik.

The Kingdom of England

Now a conqueror, Sweyn held court at the city, summoning all the jarls, shire-reeves, lawspeakers, high priests, and bishops of both Jorvik and Ostangeln. They universally elected him King in the traditional Scandinavian fashion. Thenceforth, England was governed as one kingdom with its capital at York.

Sweyn remained in England four more years, shoring up his gains and forging political alliances. In 999 he sailed in the Irish Sea to secure his western coasts. He also traveled to Dyflin to be crowned King of that city. He betrothed his son Cnut to Ingigerd, the daughter of his vanquished foe Hrolf - thus uniting the House of Gorm to the English Ragnarætten.

In 1000 Sweyn and his army secured the Welsh marches. In 1001 he journeyed to Alba to make a pact of friendship with the Scots. The Scots were delighted to have a Christian ruling to the south, but they were understandably nervous about the consolidation of England as a single power. For a hundred years the two English kingdoms had fought one another and largely left Alba alone. The new kingdom changed the balance of power on the island.

Politically, unification confirmed Jorvik as the center of power in England. Southern towns from then on looked to Jorvik, which ever since has often simply been "The City" to the English.

Sweyn Forkbeard

Sweyn Forkbeard became King of Denmark in 986 after his father's death. Though a baptized Christian, Sweyn saw faith as a very fluid thing. He did not allow his newfound salvation to temper either his ruthlessness or his practice of the religion of his ancestors. He would readily turn to both Odin and Jesus when it suited his purpose. He could behave as a pagan among pagans and a Christian among Christians. He was an ally of the religious leaders of both faiths in his realms in Denmark, England, and Ireland.

Thanks to his father's conquests in the Bloodaxe War, Sweyn's realm included the Kingdom of Östangeln in England, ruled by King Erik of Dyflin [Dublin] as a vassalage. It also included the Jarldom of Orkney and the Isles to the north of Britain.

Invasion of England

After securing his position as king with the usual round of wars and assassinations, Sweyn embarked on a campaign to expand his empire in 994. He sailed to his land in Östangeln with a large fleet. With the ships, he began attacking the eastern coasts of the kingdom of Jórvik.

In 995, Sweyn marched an army into the English Midlands. There were victories and setbacks, but word of Sweyn's ruthlessness spread throughout the country. When he campaigned in the south of England the following year, most of the Scandinavian nobility joined his side willingly. But the South was still a largely Anglo-Saxon region in which shire officials competed for influence with the feudal lords. Some of the villages sought to resist Sweyn and were virtually destroyed.

In 997, Sweyn's advance took him up along Jorvik's northeastern coast. Erik of Dyflin saw that Sweyn's conquest of the kingdom could spell the end of his own independence. He joined with Hrolf of Jorvik to fight against his erstwhile overlord. In 998, Sweyn defeated Hrolf and Erik and captured the city of Jórvik.

The Kingdom of England

Now a conqueror, Sweyn held court at the city, summoning all the jarls, shire-reeves, lawspeakers, high priests, and bishops of both Jorvik and Ostangeln. They universally elected him King in the traditional Scandinavian fashion. Thenceforth, England was governed as one kingdom with its capital at York.

Sweyn remained in England four more years, shoring up his gains and forging political alliances. In 999 he sailed in the Irish Sea to secure his western coasts. He also traveled to Dyflin to be crowned King of that city. He betrothed his son Cnut to Ingigerd, the daughter of his vanquished foe Hrolf - thus uniting the House of Gorm to the English Ragnarætten.

In 1000 Sweyn and his army secured the Welsh marches. In 1001 he journeyed to Alba to make a pact of friendship with the Scots. The Scots were delighted to have a Christian ruling to the south, but they were understandably nervous about the consolidation of England as a single power. For a hundred years the two English kingdoms had fought one another and largely left Alba alone. The new kingdom changed the balance of power on the island.

Politically, unification confirmed Jorvik as the center of power in England. Southern towns from then on looked to Jorvik, which ever since has often simply been "The City" to the English.

The Tenth Century, Part 9: The Distant Isles

Iceland had begun the the 900s as a much emptier place than OTL. Scandinavians seeking farmland found it in England and didn't need to brave the cold of Iceland. Beginning in the 950s or 60s, however, some Anglo-Norse were making the trip northward. By the late 900s, Iceland was no longer a homogenous island of Norwegians living a tribal existence: it was a polyglot island that included Gaels, Saxons, and Anglo-Norse, whose language was largely a branch of Danish.

Conflicts between these many groups persisted despite efforts to create a governing council, an Althing, in the 970s. Meetings of the chieftains frequently collapsed into fighting or brawling, and after a particularly violent confrontation in 992, the council never met again. By 1000, Icelandic society still had no unifying structures.

During the 980s or 990s, some Icelanders fleeing the civil conflicts transplanted themselves in Greenland. This settlement would lead to the discovery of North America in the following century.

At the other end of the Viking world, the Scandinavian/Varangian settlement of Russia continued as in OTL. Lergely Swedish, the Varangian settlers' opportunities in Russia had not been much affected by the POD. Some of the individuals involved might be different, but the Rurikid family was in power as in OTL.

Question, would like input

Erik the Red has been butterflied away, but some Scandinavians still end up in Greenland and later Vinland. I've been trying without success to come up with ATL names for these places. Any ideas?

Iceland had begun the the 900s as a much emptier place than OTL. Scandinavians seeking farmland found it in England and didn't need to brave the cold of Iceland. Beginning in the 950s or 60s, however, some Anglo-Norse were making the trip northward. By the late 900s, Iceland was no longer a homogenous island of Norwegians living a tribal existence: it was a polyglot island that included Gaels, Saxons, and Anglo-Norse, whose language was largely a branch of Danish.

Conflicts between these many groups persisted despite efforts to create a governing council, an Althing, in the 970s. Meetings of the chieftains frequently collapsed into fighting or brawling, and after a particularly violent confrontation in 992, the council never met again. By 1000, Icelandic society still had no unifying structures.

During the 980s or 990s, some Icelanders fleeing the civil conflicts transplanted themselves in Greenland. This settlement would lead to the discovery of North America in the following century.

At the other end of the Viking world, the Scandinavian/Varangian settlement of Russia continued as in OTL. Lergely Swedish, the Varangian settlers' opportunities in Russia had not been much affected by the POD. Some of the individuals involved might be different, but the Rurikid family was in power as in OTL.

Question, would like input

Erik the Red has been butterflied away, but some Scandinavians still end up in Greenland and later Vinland. I've been trying without success to come up with ATL names for these places. Any ideas?

Last edited:

Tenth Century supplement: Kings of Castile

By the 940s Castile was the last major Christian kingdom in Spain. Its counts assumed the title King in 942, when Leon was conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate and Asturias joined Castile. The rest of Spain was conquered by the Caliphate or the Norse.

The first two generations on this list are the same, as the marriages are not butterflied away by the Muslim victories. The first change in the Castilian line comes in the late 980s, when Astrid, the daughter of the Anglo-Norse ruler of Galicia, married Sancho, heir to Castile.

929: Proclamation of the Caliphate

Ferdinand González (930–970)

939: Battle of Simancas, Muslim victory

942: Fall of Leon (Ferdinand's feudal overlord)

949: Viking conquest of Galicia (Galisja)

950: Ferdinand defeats Caliph's armies, takes title King of Castile and Asturias

953: marries daughter to Count of Aragon

Garcia Fernandez (970-995)

974: Expands Castile's knighthood

976: Vizier Al-Mansur comes to power in Cordoba

964: Aids Hrut of Galisja in driving the English out of Compostela

990: Son rebels with Al-Mansur's support; rule essentially confined to Asturias

Sancho Garcia (995-1017) - married Astrid, daughter of King Hrut of Galisja.

995: Reunites Castile and tacitly repudiates Al-Mansur

997: Al-Mansur lays seige to Burgos; Sancho agains submits to his overlordship

1002: Death of al-Mansur; Castile again independent

By the 940s Castile was the last major Christian kingdom in Spain. Its counts assumed the title King in 942, when Leon was conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate and Asturias joined Castile. The rest of Spain was conquered by the Caliphate or the Norse.

The first two generations on this list are the same, as the marriages are not butterflied away by the Muslim victories. The first change in the Castilian line comes in the late 980s, when Astrid, the daughter of the Anglo-Norse ruler of Galicia, married Sancho, heir to Castile.

929: Proclamation of the Caliphate

Ferdinand González (930–970)

939: Battle of Simancas, Muslim victory

942: Fall of Leon (Ferdinand's feudal overlord)

949: Viking conquest of Galicia (Galisja)

950: Ferdinand defeats Caliph's armies, takes title King of Castile and Asturias

953: marries daughter to Count of Aragon

Garcia Fernandez (970-995)

974: Expands Castile's knighthood

976: Vizier Al-Mansur comes to power in Cordoba

964: Aids Hrut of Galisja in driving the English out of Compostela

990: Son rebels with Al-Mansur's support; rule essentially confined to Asturias

Sancho Garcia (995-1017) - married Astrid, daughter of King Hrut of Galisja.

995: Reunites Castile and tacitly repudiates Al-Mansur

997: Al-Mansur lays seige to Burgos; Sancho agains submits to his overlordship

1002: Death of al-Mansur; Castile again independent

Valdemar II

Banned

Erik the Red has been butterflied away, but some Scandinavians still end up in Greenland and later Vinland. I've been trying without success to come up with ATL names for these places. Any ideas?

America could be called Markland means directly Forestland, while Greenland is a likely name.

America could be called Markland means directly Forestland, while Greenland is a likely name.

I could go with Markland. But is Greenland that likely? I thought it was part of Erik the Red's marketing savvy, in that he got all these Icelanders to believe Greenland was some kind of paradise.

Valdemar II

Banned

I could go with Markland. But is Greenland that likely? I thought it was part of Erik the Red's marketing savvy, in that he got all these Icelanders to believe Greenland was some kind of paradise.

Iceland is already taken and Greenland coast is rather green in the summer and moreso at that time.

Right , I see that. But I personally would like to see a different name. Maybe the Norse equivalent of "Ivory Land" or something else referring to walrus hunting. Benland or Beinland would seem to mean "Boneland" and could refer to ivory. But I don't know any Scandinavian languages at all and am just paddling around the Internet looking for possibilities.

I do like Markland for the Americas, since it seems so obvious. I'm still unsure about the status the Viking-Americans would have in this TL. Originally I had imagined a much more viable Vinland that gradually fades into the fabric of the continent, sort of like the Kievan Rus. I also imagined the Hanseatic merchants exploiting America at a much later date. Now I'm not so sure about it.

I do like Markland for the Americas, since it seems so obvious. I'm still unsure about the status the Viking-Americans would have in this TL. Originally I had imagined a much more viable Vinland that gradually fades into the fabric of the continent, sort of like the Kievan Rus. I also imagined the Hanseatic merchants exploiting America at a much later date. Now I'm not so sure about it.

Right , I see that. But I personally would like to see a different name. Maybe the Norse equivalent of "Ivory Land" or something else referring to walrus hunting. Benland or Beinland would seem to mean "Boneland" and could refer to ivory. But I don't know any Scandinavian languages at all and am just paddling around the Internet looking for possibilities.

I do like Markland for the Americas, since it seems so obvious. I'm still unsure about the status the Viking-Americans would have in this TL. Originally I had imagined a much more viable Vinland that gradually fades into the fabric of the continent, sort of like the Kievan Rus. I also imagined the Hanseatic merchants exploiting America at a much later date. Now I'm not so sure about it.

Perhaps Norse folklore could provide the basis for names of discovered lands.

Share: