Shippen, Anne. Red Blood, Brown Water. Saint Louis: Kringle, 2003. Print.

The Neutrality movement was indistinct and hard to enforce at the best of times. The western states of Kentucky, Missouri and Illinois promised to remain loyal and follow Federal laws, but would not support the war with blood or treasure. Could the needle truly be threaded that way? The complexity of taxes, trade, movement of men and money became even more greater on the waterways, the arteries of American trade in the West.

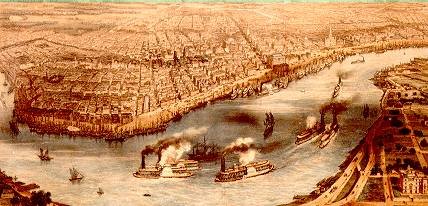

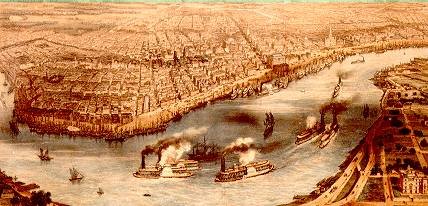

The steamboat trade had exploded in the decade or so before the outbreak of war. Hundreds of the dangerous yet vital vessels plied the waters from north of Pittsburgh to New Orleans. It was these boats that carried the corn, cotton, pork and wheat down the rivers to destinations worldwide, and had made New Orleans the fourth largest export city in the world. It was that trade that the western states were trying to protect with neutrality. While young fire-eaters like Abraham Lincoln or Stephen Douglas might talk about ‘popular sovereignty’, really it was the money that talked. Nearly all of the goods produced in those states was sent Southward to Southron ports. The age of the railway had not yet come, and commerce was firmly yoked to the rivers.

New Orleans, major trade enterport for the world

The war itself increased the trade, of course. Demand on both sides skyrocketed with the needs of armies added to those of the homefront. Everything from cotton to timber to stone to beef was needed to fuel the armies. Columbia also needed these goods for export, offsetting the lack of hard currency. Even as the partial Federal blockade hindered commerce, blockade runners (both Southron and British) made a fortune smuggling goods in and out.

Neutrality muddied waters further with states arguing that trade should be allowed ‘unhindered’ by either side. Of course, this desire was only as good as their ability to enforce it. On land they managed better, but on the water President Jackson and local Federal officers refused to submit.

As soon as war was declared both sides took to the rivers, transforming freight steamboats into ships of war. These quickly impressed rickety craft were far from the acme of naval technology on the high seas, but desperate times made for desperate measures. Both sides loaded these dangerous craft, already liable to boiler explosions, with armor and cannon. The Columbian forces, even more ramshackle, were often forced to armor their boats with cotton bales, using the one resource they had in abundance. While these ‘cottonclads’ caught the attention of the public, they inevitably performed poorly in combat, with the cotton doing little more then stopping small-arms fire. Even a well-aimed rifle shot from the newer flintlocks could penetrate, to say nothing of the heavy cannon installed on opposing boats.

Pictured is a standard steamboat of the area

To command these vessels, both nations looked to the locals who knew the ships and the river well. The United States Navy considered sending trained naval men, but such choices took time, and every trained officer was needed now to enforce the blockade at sea. Moreover, the Mississippi trade needed to be protected at once, not when an officer could finally be found who was surplus to the needs of the maritime blockade. As for the South, the lack of funds and an even greater shortage of trained personnel necessitated recruiting raw civilians.

For months, while famous battles raged in Virginia, on isolated islands and the high seas, blood was spilled in the brown water in the middle of the continent. Northern captains steamed southward to intercept and direct trade upstream, and Southron captains headed north to shepherd trade south. Meanwhile, the Western men, unable to field boats of their own, watched their fortunes slip away as trade withered.

Of course, in those early months of the summer and fall of 1837 the boats were often more of a danger to themselves than others. Steamboats, fragile vessels at the best of time, became downright deadly when loaded with heavy cannon and run by inexperienced crews hell bent on glory. Quite apart from running aground or simply sinking with all hands (the U.S.S Crane September 12), captains had a tendency to make excessive demands of the cheaply made boilers. Such tactics led to deadly explosions, often killing all onboard. This hardly dissuaded the steamboat men though. National glory aside, fortunes were being made.

The more numerous Northern ships soon captured much of the trade - capture being the operative word. Northern captains boarded any ship they could find, and sent most of the goods upriver to the ports of Ohio or Pennsylvania, and received a small portion of the goods’ value. It was a system that encouraged aggressiveness and violence. ‘No ship was safe from Pittsburgh to Memphis’ was a common rule, and more than one daring Northern captain, often flying under false colors, went even further south. On October 21st, Captain Jack Halloway of the U.S.S. Red River captured two vessels carrying cotton just north of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

This act caused outrage in Columbia at large and in New Orleans in particular. The river trade must be protected or the entire city would fall apart, not to mention it could soon bring the West into the war on the Federal side. The South had to control the waterways, both to show they were worth supporting, and to reap the obvious financial benefits of incoming goods.

To this end, eight cottonclads were gathered at Memphis and sent north to ‘give battle to the Yankees’ and win the river back for Columbia. This task force was even given an actual naval commander, Samuel Barron, at the insistence of powerful New Orleans traders and politicians. Barron, unused to river combat, proved a lackluster commander, and had soon lost one of his ships to the twisting shoals of the river. Nevertheless, he pushed on, confident his fleet was still larger than anything the North would send.

Barron was right. As news of the armada sped north, only five steamboats could be found in time to counter them. Under the command of David Jameson, an experienced steamboat captain recently turned naval officer, they rushed south, eager to ‘mix it up with the Rebels’, as Jameson put it.The two fleets met just downstream of Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio and Mississippi joined. A thriving port, it was a natural place for a struggle over the entire watershed. The locals, powerless to interfere, simply watched the fight happen from the shore.

Belching black smoke and churning the brown water to a froth, the two squadrons met near noon. At first both fleets stood off and fired their main guns at each other. Poor gunnery and positioning led to minimal results. Only one ship, the C.S. John. C. Calhoun, was taken out of the fight, one paddlewheel smashed by fire. As it became apparent cannons wouldn’t decide the combat, the Northerners sped forward and engaged at close range. It became a wild melee of pointblank broadsides, fusillades of flintlocks and, in the end, boarding parties. Better organized, and apparently better watermen, the Federals had soon won the day, capturing three ships, sinking a further three, and allowing only one to flee south. Even this eighth ship was to capsize and be lost before its crew could reach safety.

A very inaccurate and anachronistic picture of the Battle of Cairo. Note the unhistorical gun ports.

News of the Battle of Cairo took weeks to reach the East, but when it did it was lauded by all as an example of superior Northern ingenuity and technical skill. In the South it was mostly ignored, doubly so after the partial victory of Southron troops in the last major Virginian battle of the season at Chester Gap.

What the battle really did was drive a stake through the heart of neutrality. Here was open combat on the doorstep of a major neutral city. Neutral trade was being interdicted and routed to the war economies of both North and South. Federal spies and agents filled the entire West, reporting, plotting and organizing pro-Federal activity. With the state governments apparently so helpless as the tide of war rose, more than a few began to consider taking a side was a better approach then taking none.

The Neutrality movement was indistinct and hard to enforce at the best of times. The western states of Kentucky, Missouri and Illinois promised to remain loyal and follow Federal laws, but would not support the war with blood or treasure. Could the needle truly be threaded that way? The complexity of taxes, trade, movement of men and money became even more greater on the waterways, the arteries of American trade in the West.

The steamboat trade had exploded in the decade or so before the outbreak of war. Hundreds of the dangerous yet vital vessels plied the waters from north of Pittsburgh to New Orleans. It was these boats that carried the corn, cotton, pork and wheat down the rivers to destinations worldwide, and had made New Orleans the fourth largest export city in the world. It was that trade that the western states were trying to protect with neutrality. While young fire-eaters like Abraham Lincoln or Stephen Douglas might talk about ‘popular sovereignty’, really it was the money that talked. Nearly all of the goods produced in those states was sent Southward to Southron ports. The age of the railway had not yet come, and commerce was firmly yoked to the rivers.

New Orleans, major trade enterport for the world

The war itself increased the trade, of course. Demand on both sides skyrocketed with the needs of armies added to those of the homefront. Everything from cotton to timber to stone to beef was needed to fuel the armies. Columbia also needed these goods for export, offsetting the lack of hard currency. Even as the partial Federal blockade hindered commerce, blockade runners (both Southron and British) made a fortune smuggling goods in and out.

Neutrality muddied waters further with states arguing that trade should be allowed ‘unhindered’ by either side. Of course, this desire was only as good as their ability to enforce it. On land they managed better, but on the water President Jackson and local Federal officers refused to submit.

As soon as war was declared both sides took to the rivers, transforming freight steamboats into ships of war. These quickly impressed rickety craft were far from the acme of naval technology on the high seas, but desperate times made for desperate measures. Both sides loaded these dangerous craft, already liable to boiler explosions, with armor and cannon. The Columbian forces, even more ramshackle, were often forced to armor their boats with cotton bales, using the one resource they had in abundance. While these ‘cottonclads’ caught the attention of the public, they inevitably performed poorly in combat, with the cotton doing little more then stopping small-arms fire. Even a well-aimed rifle shot from the newer flintlocks could penetrate, to say nothing of the heavy cannon installed on opposing boats.

Pictured is a standard steamboat of the area

To command these vessels, both nations looked to the locals who knew the ships and the river well. The United States Navy considered sending trained naval men, but such choices took time, and every trained officer was needed now to enforce the blockade at sea. Moreover, the Mississippi trade needed to be protected at once, not when an officer could finally be found who was surplus to the needs of the maritime blockade. As for the South, the lack of funds and an even greater shortage of trained personnel necessitated recruiting raw civilians.

For months, while famous battles raged in Virginia, on isolated islands and the high seas, blood was spilled in the brown water in the middle of the continent. Northern captains steamed southward to intercept and direct trade upstream, and Southron captains headed north to shepherd trade south. Meanwhile, the Western men, unable to field boats of their own, watched their fortunes slip away as trade withered.

Of course, in those early months of the summer and fall of 1837 the boats were often more of a danger to themselves than others. Steamboats, fragile vessels at the best of time, became downright deadly when loaded with heavy cannon and run by inexperienced crews hell bent on glory. Quite apart from running aground or simply sinking with all hands (the U.S.S Crane September 12), captains had a tendency to make excessive demands of the cheaply made boilers. Such tactics led to deadly explosions, often killing all onboard. This hardly dissuaded the steamboat men though. National glory aside, fortunes were being made.

The more numerous Northern ships soon captured much of the trade - capture being the operative word. Northern captains boarded any ship they could find, and sent most of the goods upriver to the ports of Ohio or Pennsylvania, and received a small portion of the goods’ value. It was a system that encouraged aggressiveness and violence. ‘No ship was safe from Pittsburgh to Memphis’ was a common rule, and more than one daring Northern captain, often flying under false colors, went even further south. On October 21st, Captain Jack Halloway of the U.S.S. Red River captured two vessels carrying cotton just north of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

This act caused outrage in Columbia at large and in New Orleans in particular. The river trade must be protected or the entire city would fall apart, not to mention it could soon bring the West into the war on the Federal side. The South had to control the waterways, both to show they were worth supporting, and to reap the obvious financial benefits of incoming goods.

To this end, eight cottonclads were gathered at Memphis and sent north to ‘give battle to the Yankees’ and win the river back for Columbia. This task force was even given an actual naval commander, Samuel Barron, at the insistence of powerful New Orleans traders and politicians. Barron, unused to river combat, proved a lackluster commander, and had soon lost one of his ships to the twisting shoals of the river. Nevertheless, he pushed on, confident his fleet was still larger than anything the North would send.

Barron was right. As news of the armada sped north, only five steamboats could be found in time to counter them. Under the command of David Jameson, an experienced steamboat captain recently turned naval officer, they rushed south, eager to ‘mix it up with the Rebels’, as Jameson put it.The two fleets met just downstream of Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio and Mississippi joined. A thriving port, it was a natural place for a struggle over the entire watershed. The locals, powerless to interfere, simply watched the fight happen from the shore.

Belching black smoke and churning the brown water to a froth, the two squadrons met near noon. At first both fleets stood off and fired their main guns at each other. Poor gunnery and positioning led to minimal results. Only one ship, the C.S. John. C. Calhoun, was taken out of the fight, one paddlewheel smashed by fire. As it became apparent cannons wouldn’t decide the combat, the Northerners sped forward and engaged at close range. It became a wild melee of pointblank broadsides, fusillades of flintlocks and, in the end, boarding parties. Better organized, and apparently better watermen, the Federals had soon won the day, capturing three ships, sinking a further three, and allowing only one to flee south. Even this eighth ship was to capsize and be lost before its crew could reach safety.

A very inaccurate and anachronistic picture of the Battle of Cairo. Note the unhistorical gun ports.

News of the Battle of Cairo took weeks to reach the East, but when it did it was lauded by all as an example of superior Northern ingenuity and technical skill. In the South it was mostly ignored, doubly so after the partial victory of Southron troops in the last major Virginian battle of the season at Chester Gap.

What the battle really did was drive a stake through the heart of neutrality. Here was open combat on the doorstep of a major neutral city. Neutral trade was being interdicted and routed to the war economies of both North and South. Federal spies and agents filled the entire West, reporting, plotting and organizing pro-Federal activity. With the state governments apparently so helpless as the tide of war rose, more than a few began to consider taking a side was a better approach then taking none.