Lombardi, Bruno. A History of Canada. Montreal: Smith Printing, 2003. Print.

Much like the Columbian Rebellion, the unrest that wracked Canada from 1837-38 had deep roots. Canada had long been governed under archaic laws, that treated the nation as a mere colony with little right to self-rule, even as the revolutions in America, the Caribbean and South America showed the folly of this approach. The franchise was limited, political corruption rampant and Great Britain still appointed unpopular governors with near dictatorial powers. Aptly, it was the successes of the Reform Movement in the motherland that inspired the same moves in Canada.

It should be clearly noted that while often treated as one country in American histories, Canada was quite two separate governmental entities at this time. There was Upper Canada, generally the Anglo region around the Great Lake, which included large and growing cities like Toronto and Windsor. In this region it was generally Anglo settlers agitating for equal political rights, which were being won in Britain but denied here.

Toronto, a growing center of trade and goverment, the face of a changing Canada

There was also lower Canada, later the region known as Quebec. It was populated by French-speaking Catholic settlers, or Canadiens, left over from when Britain had taken Quebec from France in the Seven Years War. Along with the nature grievances of faith and language, they were also unsettled by talk of combining both colonies together, the better to dilute French influence.

By 1837 the tensions had finally, after years of political strife, risen to violence. Both areas had quite independently erupted into violence at the same time. In Lower Canada an assembly of French protesters refused to be arrested and responded with violence. Things escalated as the government brought in more troops, while the rebels fled into the countryside, razing it behind them. The main rebel leader, Louis-Joseph Papineau, a veteran of 1812 and a longtime lawyer, advocated boycott and civil resistance more than outright rebellion. Ironically, the main rebel that advocated violence was an Anglo named Wolfred Nelson, a former physician turned failed politician. Throughout the summer the two of them whipped Lower Canada into a frenzy, stocking arms, gathering recruits and by fall attacking small British forces with varying success. Papineau fled to the United States, trying to find aid for the revolt.

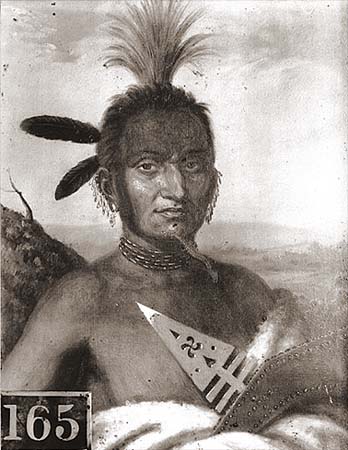

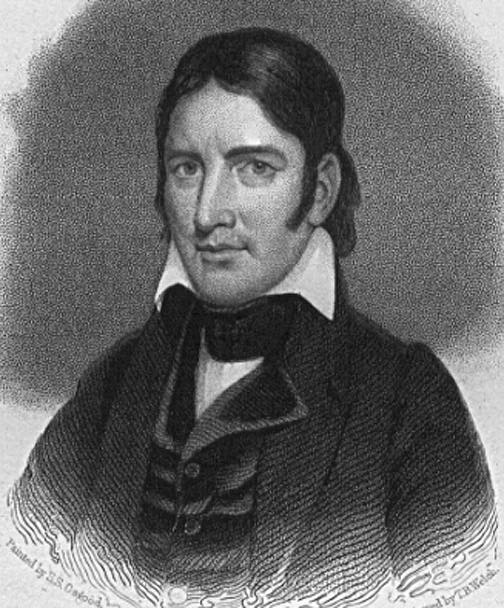

At the same time, Upper Canada also exploded into revolt. With government troops drawn to Lower Canada, the time was ripe for political radicals to try and seize power. In October 1837 a riot broke out in Toronto, which was barely put down. In the aftermath a group of radicals gathered in a Constitutional Convention headed by Lyon Mackenzie, a staunch republican. After voting on a new Constitution for Lower Canada, they declared themselves in revolt.

Lyon Mackenzie, fervent but sometimes unstable Republican leader

At first they tried peaceful means and hoped that, having won enough rural support, they could simply march into the cities with a fait accompli. However, despite being undermanned, government forces reacted swiftly, and at Montgomery's Tavern sought to force the issue with the bayonet. Mackenzie wanted to stay and fight, but was outvoted. The rebels fled, growing more violent every passing day. In December they were forced to a pitched battle at Hamilton, and lost. The Republicans fled to Navy Island, hoping, like their Canadien cousins, for American support.

Both revolts seemed lost in the cold winter of 1837-38. Most of the leaders in both areas had been driven to the United States and their small armies defeated in the field. If relations between the United States and the United Kingdom had been warm it probably would have ended there. As things stood, though, President Jackson saw these rebels as tools to use against Canada, and, by extension, Great Britain.

He sent food, money and arms to the rebels and helped organize the so-called ‘Hunters Lodges’, bases for the rebels to use in American territory. Lewis Cass, the humiliated general now in charge of the Michigan border, was instructed to ‘provide these men all due aid and respect’. Soon the Great Lakes were full of ships supporting the now recovering rebels. Papineau met Federal agents in New York who provided funds and weapons (although powder was in critically short supply) to the beleaguered Canadiens. Even Mackenzie on Navy Island was provided with regular shipments of food and money, which emboldened the man to declare a Republic of Canada on January 18th.

With all this American aid, instead of the revolts withering, they grew over that winter and when spring came, the leaders once again took to the field. In Lower Canada the French peasants rose up in greater numbers than the previous year, and now had experienced military leaders. Men like Ferdinand-Alphonse Oklowski and Jean-Olivier Chénier were among them. Chenier in particular led his ragged force to victory after victory in those heady days of early 1838. Soon the revolt grew into a real threat to the government forces as the rebels threatened cities like Quebec City and even the newly founded Montreal.

These successes were matched in Upper Canada. Bolstered by American goods and money, Republican forces led by Anthony Van Egmond, a supposed veteran of the Napoleonic wars, took the initiative. The rebels had narrow victories at Moore’s Field and Nelson. Mackenzie himself, still based on Navy Island, actually hijacked a steamboat and threatened trade all over the Niagara region.

The run of victories could not last, however, not with American attention diverted south as their own war heated up for the summer. Both Lower and Upper Canada demanded more British troops be sent. Parliament, increasingly worried about American tensions in the Atlantic agreed and sent thousands of troops. These battle-hardened troops, well fed and led by men such as Roger Sheaffe (a former Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada) and Charles Napier (recently home from India) quickly moved to quash both rebellions. Great Britain, concerned with American involvement in Canada, had broken with tradition and told her commanders to deal harshly with traitors and ‘foreign agents’.

Lower Canada fell first, with the Canadiens first chased into rough, rural country and then slowly beaten down into a poor hungry rabble. Upon capture, dozens of men were hanged and hundreds transported to Australia with little regard for innocence or guilt. A secondary revolt in the fall was bloodily put down, increasing the hatred between French speaking and English speaking groups.

The hopeless 'Second Rebellion' in Quebec being crushed by British troops

In Upper Canada, things took more time. The rougher terrain, the informal ‘navy’ gifted by America, and the resolute nature of Mackenzie all lent themselves to a long rebellion. Napier, aged but brutal, has his own views on rebellion from his days in India.

“The best way to quiet a country is a good thrashing, followed by great kindness afterwards. Even the wildest chaps are thus tamed.”

He lived up to his reputation. He burned towns, scorched fields, and bombarded cities that dared side with the Republicans. Prisoners were generally shot or hanged, and the laws of war were removed. The entire province of Upper Canada was declared under martial law and treated harshly. Civilians were interrogated, supplies requisitioned and no little quarter given. This harsh attitude also showed when dealing with the rebels themselves. When Egmond, holding out in a rough fortress, refused to surrender, Napier sent a simple message.

“Come here instantly. Come here at once and make your submission, or I will in a week tear you from the midst of your troops and hang you.”

Egmond, leading troops with no shoes, food or weapons surrendered on September 22nd. With that, the final flickers of Republican revolt were extinguished by the British troops. Mackenzie once again retreated to Navy Island, which he fortified and manned to withstand any assault. He hoped America would save him once again, but by now Jackson was far too concerned with Columbia, and could spare nothing for the northern rebels. On October 12th, the British heavily shelled Navy Island. After dark, veterans slipped ashore and stormed the poorly manned defenses. Although they watered the ground with blood, they nonetheless captured Mackenzie alive. He was then hanged by a vengeful army, along with many of his most loyal lieutenants.

While both armed insurrections had failed, their uprisings and the brutal British re-conquest fed an underground fire for Republicanism in Canada for decades to come, in both English-speaking and French-speaking hearts.