You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The American Experiment- A Nullification Timeline

- Thread starter The Tai-Pan

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Been reading this entire TL from start to finish and I'm definitely liking what I'm seeing so far; it even kinda reminds me of a TL I was working on that had an earlier Civil War planned(although it's been unofficially shelved for now). WI wonder where this'll go next?

And with that in mind, to @The Tai-Pan , if you do decide to turn Columbia into an utterly planter-dominated state, if anything does change much from OTL in that particular regard, it would almost certainly would be more religious than the OTL South, not less.

Thanks! I hope it goes to fun and interesting places.

I actually have a flag in mind...will be revealed soon....

Steed, William F., Dr. The American War of Secession: A Study in Contrasts. 4th ed. Vol. 1. London: Imperial, 1956. Print. A History of North America.

It is important to study the information available to Lewis Cass before we pass judgement on his command choices. It can be difficult to separate our views and myths of a war, campaign or battle from the actual information available to the participants. Many of the ‘classic blunders’ and errors in history can be ascribed to someone simply not knowing what the omnipresent and reviewing historian later knows. With this in mind, it is good to review Cass’s views, opinions and available facts.

Impossible to overstress was the impact of the president on Lewis Cass’s mindset and view of the events. Jackson and Cass had had many long meetings before Cass departed South with his army, and like so often happened Jackson’s interpretation of events became the only interpretation. Jackson’s view that the South needed to be taught a ‘swift, sharp lesson’, led to the obvious corollary that speed was important. Cass needed to rush South, and strangle the rebellion before it grew too entrenched. This political command sped the general onward.

Another factor that urged swiftness was the makeup of the command itself. Cass’s army was mostly made of regulars along with a smattering of state volunteers. The draft, passed and ongoing, would take months to come to fruition. Cass has a Regular’s disdain for draftees. Privately, he wondered why the draft had been undertaken at all and what sort of soldiers would be churned out by the complicated and corrupt process. Speed would allow him to win battles before being saddled with thousands of men looking to ‘get out of work, get out of trouble and get out of here’.

Thirdly, and often overlooked, was the lack of information about the enemy and his strength. Cass, like everyone in Washington, assumed it would take many months before Columbia could field an army and send it north to protect Virginia. It was only July and Cass was already nearly halfway to Richmond. It was vital to move quickly and reach key Southern cities before the enemy had time to assemble. Cass assumed he would only be meeting local militia and perhaps some Virginia volunteers (some of which may very well fight on his side).

Of course, we now know it was already too late. The men in Columbia had moved quickly, and David Twiggs marched north at a breakneck pace. Even as Cass pushed south, Twiggs, along with most of his bedraggled army, was already between him and Richmond.

For his part, Twiggs had little idea where Cass was or the strength of the Federal forces. Personally, he felt he needed a great victory though, to even give Columbia an even chance of success on a larger scale. A pyrrhic victory or even a draw might save Richmond in the short run, but only a truly resounding triumph would give enough support to the secessionists in the South. So, pushed by his own concerns, Twiggs sought a Grand Battle that would decide the shape of the upcoming campaign for least several months.

The story of Cass’s missing cavalry has entered popular legend, but going over it from Cass’s point of view is instructive. Cass had ordered his cavalry, under James Miller, to scout and screen ahead for whatever enemies did exist in the rough Virginia landscape. Miller, obviously unused to the terrain, promptly got lost and spent days wandering west far from Cass’s path, and out of contact with the Army of the East. Without knowing Miller was lost, Cass simply thought little was happening until it was too late. Infrequent reports were not uncommon in this period, and the lack of information from Miller did not mean disconnect. It would prove to be a vital mistake.

Also commonly used to attack Cass was the skirmish at Hoadly. Cass received reports of Virginia militia off to his right, to the west. Assuming these were the militia forces he expected, he easily drove them off, but they retreated in good order, threatening his rear. He could not leave intact forces behind him, but stopping the whole march for a few disorganized militia was impractical. He would have to divide his force, somewhat. Distrusting the green state volunteers, Cass detached a strong force of his Regulars to hold, and if possible hunt down, the rogue militia forces. Content that he had dealt with the only foe in the field, Cass resumed his march south, hurrying as quickly as possible.

So it can be seen how a small series of errors, lack of information and sheer chance led the careful and prudent Cass to have an army strung out, lacking cavalry and missing a core of experienced troops. If Cass had faced the reality he thought, a wide open road to Richmond, his choices would be commended. History is rarely so kind.

A last chance to alter this course came at Dumfries, Virginia. Scattered reports came to Cass that a strong force of the enemy were taking up positions across Quantico Creek. Cass wondered who it could be. Another force of Virginia militia? Perhaps Virginia state volunteers hastily scrabbled together? In any case, they had to be moved.

[The following was helpfully war-gamed for me by Mr. P. A slight change in style. All mistakes are mine!]

Cass planned to manoeuvre Rigel’s 1st Division (6 regiments of regulars, and with attached artillery) to a bridge across the stream by the town of Dumfries. On its right was to be the ‘Irish’ 4th Division (6 regiments of militia). On its left, Wheztel’s 3rd Division (6 regiments of militia). Harrison’s 2nd Division (6 regiments of regulars and some more artillery) was stuck in soft Virgina mud, so the original plan was for them to form up behind 1st Division, and offer support. The cavalry brigade (2 regiments of regulars) was to move up on the extreme left flank. Once in position, there was to be an all-out Federal assault, preceded by a cannonade. The few cavalry on hand were to envelop the Southerners' right flank. Things did not go to plan.

The Southron plan, such as there was, simply to sit on the southern bank of the stream, and wait for the Northerners to attack, but as it turned out fate had other plans. Reep’s Second Division (8 regiments of militia) was to the west of the bridge, Holler’s Third Division (8 regiments of militia) to the east. The Cavalry (Smith’s) Division (4 regiments of regulars and the horse artillery) was just to the south of the bridge, threatening any Northern infantry that dared cross it with a sabre charge.

The green Northern forces became fragmented in the face of the enemy as they advanced against fairly fixed positions. 4th Division left itself in a precarious position as it tried to assume its post on the Northern army's right flank. Seeing an opportunity, the Southron commander threw in Cavalry and Second Division (the left flank) against the Northern 4th Division. Not having anticipated this attack, severely outnumbered, and hit simultaneously in the front and flank, the Northern militia disintegrated, pouring north, and clogging the road to the detriment of the regulars in the North's 1st Division attempting to push forward. The crumbling of the 4th Division, made of a disportionate number of Irish would cast a long shadow, past this battlefield.

At last realising the threat posed by the Southrons, the Cass acted decisively, and began recalling 1st Division (the regulars), 3rd Division (militia) and the cavalry brigade in an attempt to salvage the situation. It was one thing to assault a mishmash of local troops but obviously that was not the case, and it was time to retreat and regroup.

Unfortunately, even as these orders were received, the Southron First Division burst from the woods, falling on the flank of the Northern 1st Division, and badly mauling it. The regulars fell back across a smaller, northerly stream, abandoning their artillery to the Southrons. 2nd Division (the other regulars and artillery) covered their retreat. Twiggs, in a nearly religious fervor, ordered a general Southron advance, and the Northern 3rd Division (militia) was surrounded and nearly destroyed in detail. Only a few tattered remains fled north to the retreating Federal forces.

It is important to study the information available to Lewis Cass before we pass judgement on his command choices. It can be difficult to separate our views and myths of a war, campaign or battle from the actual information available to the participants. Many of the ‘classic blunders’ and errors in history can be ascribed to someone simply not knowing what the omnipresent and reviewing historian later knows. With this in mind, it is good to review Cass’s views, opinions and available facts.

Impossible to overstress was the impact of the president on Lewis Cass’s mindset and view of the events. Jackson and Cass had had many long meetings before Cass departed South with his army, and like so often happened Jackson’s interpretation of events became the only interpretation. Jackson’s view that the South needed to be taught a ‘swift, sharp lesson’, led to the obvious corollary that speed was important. Cass needed to rush South, and strangle the rebellion before it grew too entrenched. This political command sped the general onward.

Another factor that urged swiftness was the makeup of the command itself. Cass’s army was mostly made of regulars along with a smattering of state volunteers. The draft, passed and ongoing, would take months to come to fruition. Cass has a Regular’s disdain for draftees. Privately, he wondered why the draft had been undertaken at all and what sort of soldiers would be churned out by the complicated and corrupt process. Speed would allow him to win battles before being saddled with thousands of men looking to ‘get out of work, get out of trouble and get out of here’.

Thirdly, and often overlooked, was the lack of information about the enemy and his strength. Cass, like everyone in Washington, assumed it would take many months before Columbia could field an army and send it north to protect Virginia. It was only July and Cass was already nearly halfway to Richmond. It was vital to move quickly and reach key Southern cities before the enemy had time to assemble. Cass assumed he would only be meeting local militia and perhaps some Virginia volunteers (some of which may very well fight on his side).

Of course, we now know it was already too late. The men in Columbia had moved quickly, and David Twiggs marched north at a breakneck pace. Even as Cass pushed south, Twiggs, along with most of his bedraggled army, was already between him and Richmond.

For his part, Twiggs had little idea where Cass was or the strength of the Federal forces. Personally, he felt he needed a great victory though, to even give Columbia an even chance of success on a larger scale. A pyrrhic victory or even a draw might save Richmond in the short run, but only a truly resounding triumph would give enough support to the secessionists in the South. So, pushed by his own concerns, Twiggs sought a Grand Battle that would decide the shape of the upcoming campaign for least several months.

The story of Cass’s missing cavalry has entered popular legend, but going over it from Cass’s point of view is instructive. Cass had ordered his cavalry, under James Miller, to scout and screen ahead for whatever enemies did exist in the rough Virginia landscape. Miller, obviously unused to the terrain, promptly got lost and spent days wandering west far from Cass’s path, and out of contact with the Army of the East. Without knowing Miller was lost, Cass simply thought little was happening until it was too late. Infrequent reports were not uncommon in this period, and the lack of information from Miller did not mean disconnect. It would prove to be a vital mistake.

Also commonly used to attack Cass was the skirmish at Hoadly. Cass received reports of Virginia militia off to his right, to the west. Assuming these were the militia forces he expected, he easily drove them off, but they retreated in good order, threatening his rear. He could not leave intact forces behind him, but stopping the whole march for a few disorganized militia was impractical. He would have to divide his force, somewhat. Distrusting the green state volunteers, Cass detached a strong force of his Regulars to hold, and if possible hunt down, the rogue militia forces. Content that he had dealt with the only foe in the field, Cass resumed his march south, hurrying as quickly as possible.

So it can be seen how a small series of errors, lack of information and sheer chance led the careful and prudent Cass to have an army strung out, lacking cavalry and missing a core of experienced troops. If Cass had faced the reality he thought, a wide open road to Richmond, his choices would be commended. History is rarely so kind.

A last chance to alter this course came at Dumfries, Virginia. Scattered reports came to Cass that a strong force of the enemy were taking up positions across Quantico Creek. Cass wondered who it could be. Another force of Virginia militia? Perhaps Virginia state volunteers hastily scrabbled together? In any case, they had to be moved.

[The following was helpfully war-gamed for me by Mr. P. A slight change in style. All mistakes are mine!]

Cass planned to manoeuvre Rigel’s 1st Division (6 regiments of regulars, and with attached artillery) to a bridge across the stream by the town of Dumfries. On its right was to be the ‘Irish’ 4th Division (6 regiments of militia). On its left, Wheztel’s 3rd Division (6 regiments of militia). Harrison’s 2nd Division (6 regiments of regulars and some more artillery) was stuck in soft Virgina mud, so the original plan was for them to form up behind 1st Division, and offer support. The cavalry brigade (2 regiments of regulars) was to move up on the extreme left flank. Once in position, there was to be an all-out Federal assault, preceded by a cannonade. The few cavalry on hand were to envelop the Southerners' right flank. Things did not go to plan.

The Southron plan, such as there was, simply to sit on the southern bank of the stream, and wait for the Northerners to attack, but as it turned out fate had other plans. Reep’s Second Division (8 regiments of militia) was to the west of the bridge, Holler’s Third Division (8 regiments of militia) to the east. The Cavalry (Smith’s) Division (4 regiments of regulars and the horse artillery) was just to the south of the bridge, threatening any Northern infantry that dared cross it with a sabre charge.

The green Northern forces became fragmented in the face of the enemy as they advanced against fairly fixed positions. 4th Division left itself in a precarious position as it tried to assume its post on the Northern army's right flank. Seeing an opportunity, the Southron commander threw in Cavalry and Second Division (the left flank) against the Northern 4th Division. Not having anticipated this attack, severely outnumbered, and hit simultaneously in the front and flank, the Northern militia disintegrated, pouring north, and clogging the road to the detriment of the regulars in the North's 1st Division attempting to push forward. The crumbling of the 4th Division, made of a disportionate number of Irish would cast a long shadow, past this battlefield.

At last realising the threat posed by the Southrons, the Cass acted decisively, and began recalling 1st Division (the regulars), 3rd Division (militia) and the cavalry brigade in an attempt to salvage the situation. It was one thing to assault a mishmash of local troops but obviously that was not the case, and it was time to retreat and regroup.

Unfortunately, even as these orders were received, the Southron First Division burst from the woods, falling on the flank of the Northern 1st Division, and badly mauling it. The regulars fell back across a smaller, northerly stream, abandoning their artillery to the Southrons. 2nd Division (the other regulars and artillery) covered their retreat. Twiggs, in a nearly religious fervor, ordered a general Southron advance, and the Northern 3rd Division (militia) was surrounded and nearly destroyed in detail. Only a few tattered remains fled north to the retreating Federal forces.

Bull Run 25 years earlier......

And so much for Lewis Cass' military career after this. Most likely Taylor or Scott will be the preferred choice now.

And so much for Lewis Cass' military career after this. Most likely Taylor or Scott will be the preferred choice now.

Bull Run 25 years earlier......

And so much for Lewis Cass' military career after this. Most likely Taylor or Scott will be the preferred choice now.

Bull Run was actually quite worse, strictly speaking. This is more of a physiological shock.

Bull Run was actually quite worse, strictly speaking. This is more of a physiological shock.

Yeah, i just mean first battle is a northern loss, southern win.

Steed, William F., Dr. The American War of Secession: A Study in Contrasts. 4th ed. Vol. 1. London: Imperial, 1956. Print. A History of North America.

Even as armies clashed in Northern Virginia, the war at sea was already underway.

The war had not caught the United States Navy unawares, like the rest of the nation. Jackson, forceful and direct, had pulled many ships out of Southern stations or at least had them prepare to make way at short notice, lest they fall into the hands of the enemy. The move had saved many ships and crippled the secessionists’ bid for a real navy. Unlike the stores of weapons and goods on land, most of the fleet remained in Federal control and was on a war footing as the political situation collapsed.

Norfolk Naval Yards being emptied by Federal troops

That said, the Navy itself was not the mighty weapon of war it would later become. Jackson was no friend of the navy. A land commander, with little appreciation for naval combat and more than a little suspicious of the international trade any navy was built on, had starved the navy for years. Not only that, reduced government spending had reduced the quality and quantity of naval stores throughout the nation.

At the start of the conflict, the American Navy was laughable compared to the major powers, such as Great Britain or France. It consisted, including ships in repair and on the stocks, of 12 ships of the line, 17 frigates and 22 smaller ships. This at a time when overseas ships alone of the Royal Navy numbered over one hundred vessels.

Even his meager force was divided between North and South when the war broke out. The North, the home of the shipping and maritime industries (not to mention the site of the major naval yards) got the bulk of it, of course.

Nine Ships of the Line, 74 guns each, is what Jackson had to work with. The Columbus, Independence, Ohio, Washington, Franklin, Alabama, Vermont, Virginia and the Pennsylvania. These ships, along with 12 frigates and the lion’s share of the lesser ships made up the entire United States Navy, and two of those frigates were in the Pacific. With these meager resources, Jackson was faced with subduing over 2,000 miles of hostile coastline. The navy would have to support land campaigns, defend Northern shipping, assist in Federal landings as well as interrupt Southron merchant shipping.

An American warship

At least the North had the apparatus of ports, supplies and naval tradition to support the small force. The even more pathetic Southern forces lacked even those tiny advantages. The South was one of the greatest export nations on earth, but the great ships that docked there were not built there, or maintained there or even crewed from there. The few ships that fell into Columbia's hands were without supplies, experienced crews or decent repair facilities.

Even the administration of the navy was primitive. While the Columbian Secretary of the Navy, Abel Upshur, was a capable and innovative man with an amatuer eye for the navy, he was nearly alone. He had no staff, no money and very little enthusiasm with which to work. While most of the planters and politicians of Columbia appreciated the value of international trade, and a navy to protect it, few had any idea about how to go about creating and maintaining such a fleet. At least the demands were direct, if not simple. Upshur was told to maintain as much international trade as possible and raid the Northern merchant fleet. He wasn’t given much attention other than these demands. It would take time for the Virginian to come up with a way for the cash-strapped and land-based nation to effectively compete at sea.

Abel Upshur, naval dilettante

In the meantime, the North was moving ahead. While President Jackson predicted a short war, even he knew the potential power of a blockade on the South. Following the advice of Winfield Scott, Jackson began exploring how to cut off trade to the South. After long discussions with Daniel Webster, the Federal Secretary of State, Jackson had two legal options. He could close the Southern ports to outside trade as an internal affair, or he could declare a blockade of a belligerent. The second would give Columbia some degree of recognition but the first would be much harder to sell to outside powers. A port closure would require foreign powers to not send ships to those ports and for the American navy to board and investigate any ships that headed in those directions.

Jackson supported a port closure, regardless of political repercussions. It would be easier to enforce, would treat the South as mere rebels and would send a strong message overseas. Daniel Webster, a confirmed Anglophile, was horrified at the suggestion, knowing the Royal Navy would never stand for constant inspections on the high seas. In desperation he brought in British Ambassador Henry Fox in an attempt to dissuade Jackson from this course. The argument was long, contentious and ultimately fruitless. The President would not be swayed from his course.

Henry Fox, British Ambassador and unable to change Jackson's course

A defeated and slightly embittered Webster said the choice would ‘cast a long shadow’. He would be right.

Even as armies clashed in Northern Virginia, the war at sea was already underway.

The war had not caught the United States Navy unawares, like the rest of the nation. Jackson, forceful and direct, had pulled many ships out of Southern stations or at least had them prepare to make way at short notice, lest they fall into the hands of the enemy. The move had saved many ships and crippled the secessionists’ bid for a real navy. Unlike the stores of weapons and goods on land, most of the fleet remained in Federal control and was on a war footing as the political situation collapsed.

Norfolk Naval Yards being emptied by Federal troops

That said, the Navy itself was not the mighty weapon of war it would later become. Jackson was no friend of the navy. A land commander, with little appreciation for naval combat and more than a little suspicious of the international trade any navy was built on, had starved the navy for years. Not only that, reduced government spending had reduced the quality and quantity of naval stores throughout the nation.

At the start of the conflict, the American Navy was laughable compared to the major powers, such as Great Britain or France. It consisted, including ships in repair and on the stocks, of 12 ships of the line, 17 frigates and 22 smaller ships. This at a time when overseas ships alone of the Royal Navy numbered over one hundred vessels.

Even his meager force was divided between North and South when the war broke out. The North, the home of the shipping and maritime industries (not to mention the site of the major naval yards) got the bulk of it, of course.

Nine Ships of the Line, 74 guns each, is what Jackson had to work with. The Columbus, Independence, Ohio, Washington, Franklin, Alabama, Vermont, Virginia and the Pennsylvania. These ships, along with 12 frigates and the lion’s share of the lesser ships made up the entire United States Navy, and two of those frigates were in the Pacific. With these meager resources, Jackson was faced with subduing over 2,000 miles of hostile coastline. The navy would have to support land campaigns, defend Northern shipping, assist in Federal landings as well as interrupt Southron merchant shipping.

An American warship

At least the North had the apparatus of ports, supplies and naval tradition to support the small force. The even more pathetic Southern forces lacked even those tiny advantages. The South was one of the greatest export nations on earth, but the great ships that docked there were not built there, or maintained there or even crewed from there. The few ships that fell into Columbia's hands were without supplies, experienced crews or decent repair facilities.

Even the administration of the navy was primitive. While the Columbian Secretary of the Navy, Abel Upshur, was a capable and innovative man with an amatuer eye for the navy, he was nearly alone. He had no staff, no money and very little enthusiasm with which to work. While most of the planters and politicians of Columbia appreciated the value of international trade, and a navy to protect it, few had any idea about how to go about creating and maintaining such a fleet. At least the demands were direct, if not simple. Upshur was told to maintain as much international trade as possible and raid the Northern merchant fleet. He wasn’t given much attention other than these demands. It would take time for the Virginian to come up with a way for the cash-strapped and land-based nation to effectively compete at sea.

Abel Upshur, naval dilettante

In the meantime, the North was moving ahead. While President Jackson predicted a short war, even he knew the potential power of a blockade on the South. Following the advice of Winfield Scott, Jackson began exploring how to cut off trade to the South. After long discussions with Daniel Webster, the Federal Secretary of State, Jackson had two legal options. He could close the Southern ports to outside trade as an internal affair, or he could declare a blockade of a belligerent. The second would give Columbia some degree of recognition but the first would be much harder to sell to outside powers. A port closure would require foreign powers to not send ships to those ports and for the American navy to board and investigate any ships that headed in those directions.

Jackson supported a port closure, regardless of political repercussions. It would be easier to enforce, would treat the South as mere rebels and would send a strong message overseas. Daniel Webster, a confirmed Anglophile, was horrified at the suggestion, knowing the Royal Navy would never stand for constant inspections on the high seas. In desperation he brought in British Ambassador Henry Fox in an attempt to dissuade Jackson from this course. The argument was long, contentious and ultimately fruitless. The President would not be swayed from his course.

Henry Fox, British Ambassador and unable to change Jackson's course

A defeated and slightly embittered Webster said the choice would ‘cast a long shadow’. He would be right.

A great update! It looks like Jackson (never an Anglophile at the best of times) is going to seriously step in it and anger the British government. That would be ... bad. Interesting update on the navy of the era; a topic which I am not well versed in at all.

Very good indeed! I think we shall all look forward to further episodes of this lovely story.

Peterson, James. The Mountain War: The Appalachians in the War of Secession. San Francisco: Bay, 1999. Print.

Throughout the late summer, the war looked unpromising to the North. While Cass had reformed the army in northern Virginia after the debacle at Dumfries, thereby saving the capital from an invasion of Southrons, he still headed north to slander and dismissal from an irate President Jackson. Even the successful, but bloody repulse of Columbian forces at Colchester did nothing to revive the New Hampshire general’s chances. He was replaced by Alexander Macomb, a hero of the War of 1812 and a reformer. Still it was a bitter blow to Jackson to replace a loyal political ally like Cass with someone who held no personal allegiance to him.

Alexander Macomb, the new Federal commander in Northern Virginia

Things also looked poorly at sea, despite the natural advantages of the North. The Federal Navy was having a difficult time blockading the vast Columbian shoreline. Even now the policy of ‘port closure’ was proving difficult as several British and French vessels refused to be boarded. Throughout late summer and early fall tensions rose on the high seas.

With much of the West still locked in resolute neutrality, it was proving difficult to truly grapple with the Southern foe. The president called for a ‘bold stroke’ to be planned an unleashed against the rebels. A number of plans were proposed, ranging from a naval invasion of New Orleans to invading Kentucky, violating that state’s neutral borders. Anything or anything that would strike at the increasingly untied Columbian foe.

All these plans would take time, however, and the establishment of Federal naval supremacy. The President needed a victory now to raise the already flagging political morale of the North. Jackson needed to put on a show of Northern ability and victory. He found his stage in northwest Virginia, a land divided against it itself, a microcosm of America.

This distant and remote region of Virginia had always been a land apart. The plantation style economy of cotton and tobacco had never taken root in the rocky mountainous soil. Instead it was a land of smallhold farmers, living subsistence lifestyles among the hills. Politically, it was divorced completely from the rich and powerful lowlands. Virginia spent little money on the distant western portions of the state, leaving it road-poor. As recently as 1829, Virginia had voted on a new Constitution, which had advantaged the slave holding regions of the state. Not one county ‘past the mountains’ had affirmed it and its passage had led to bitter feelings on all sides.

The Nullification crisis had only deepened the divide. The poor white farmers of northwest Virginia cared little for the issues of tariffs, Federal occupation of South Carolina or slavery. If anything, they saw these as blows against a planter aristocracy by the eternal friend of the downtrodden, President Jackson. When war had broken out, the mountain counties had refused to answer the call, and any Columbian agent in the hills was marked for violence.

Still, it was a vital region. Not only was it a part of the cherished ‘Old Dominion’, northwest Virginia was a mineral rich region that allowed access to key Northern areas such increasingly industrial Pittsburgh and the vital trade route of the Ohio River valley. Holding those mountainous regions was key, regardless of the feelings of the locals and the forbidding landscape.

Columbia had few forces to spare, even in these early heady days, and a post in the wild backcountry full of rebels was not a highly desired post. It was assigned to Richard Call, a veteran of the war of 1812 and once a Jackson ally. Like so many, he had turned to the Whigs after Jackson’s occupation of South Carolina and third term nomination. A wealthy plantation owner and slaveholder, he seemed the picture of Southron nobility as he took his small force into the ridges and valleys of northwest Virginia, even as the Battle of Dumfries raged to the east.

He found a land in chaos. The local government had broken down, men were in arms, roads unsafe. Fields lay untended, mines closed, and no official was safe. With backing from Richmond, and later Columbia, Call took harsh measures against these rebels. Arrests without trial, unprovoked search and seizure and a general call for martial law in the mountain counties restored some order, but only increased the hostile feelings in the territory. It was this powder-keg President Jackson saw as an opportunity.

He sent a force under Edmund P. Gaines, a valiant and aged veteran of the the war of 1812 and various Indian conflicts. As with so many schemes of Jackson, Gaines’ appointment served another purpose. The esteemed general was a harsh critic of Jackson, despite staying loyal to the North. For years he had been a thorn in the side of the President, as well as of Winfield Scott, now the most powerful man in the army. Gaines had long considered himself more fit for the post then Scott and had let the nation know it. Sending him to northwest Virginia was as good a way as any to remove him from the political scene.

Edmund P. Gaines, foe of both President Jackson and Commander Winfeld Scott

Still, Gaines was a competent commander and despite the small force given to him, he soon began to make inroads. Entering the state in September, he moved fast through the rough terrain, hoping to secure good lodgings before winter came. He and his men fought a sharp action against local Columbian forces at Clarksburg, forcing the Southrons back, and then again at the Battle of Bickle Knob where Gaines frequently exposed himself to enemy fire.

It was soon revealed Gaines had not only a talent for leading his men through mazes of mountains and forests, but also of recruiting locals to his cause. The rebelling Virginians rallied to his flag, providing not only the food and fodder he needed, but priceless intelligence and talented guides. While Washington, D.C. disapproved of such widespread use of Southerners and arming them (Gaines would face a court-martial over disobeying orders to cease and desist), it was the use of local guides that allowed him to overcome Columbian General Call at Gauley River, where he neatly outflanked the Columbians and forced them in disarray against the river.

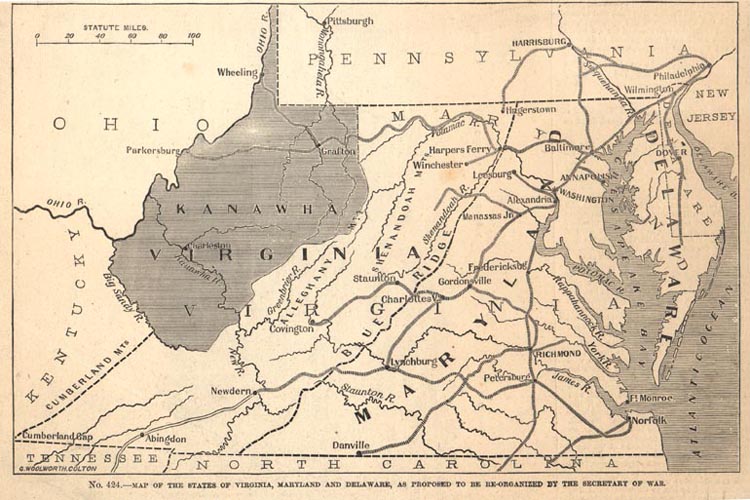

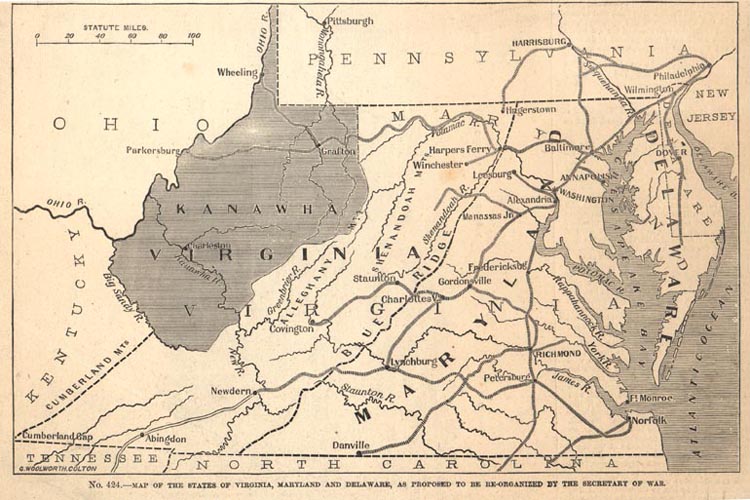

Gaines had won the victory Jackson had sought, and as the leaves fell Federal forces controlled most of northwest Virginia. Ever mindful of his local allies, Gaines advocated setting up a new state carved out of enemy territory named Kanawha, after a prominent river. He had the support of a ramshackle assembly that met in October at Wheeling. The assembly advocated for a ‘new and vigorous’ state to be formed under the protection of Federal forces. Despite Gaines’ support, however, the movement faltered when Congress and Jackson, in a rare moment of agreement, turned the offer down, saying that it would give too much credence to the Virginian secession.

One of the early proposals for the new state of Kanawha

While this disappointed the locals, it still left Gaines (and the North) in solid control of northwest Virginia and eyes towards the South.

Throughout the late summer, the war looked unpromising to the North. While Cass had reformed the army in northern Virginia after the debacle at Dumfries, thereby saving the capital from an invasion of Southrons, he still headed north to slander and dismissal from an irate President Jackson. Even the successful, but bloody repulse of Columbian forces at Colchester did nothing to revive the New Hampshire general’s chances. He was replaced by Alexander Macomb, a hero of the War of 1812 and a reformer. Still it was a bitter blow to Jackson to replace a loyal political ally like Cass with someone who held no personal allegiance to him.

Alexander Macomb, the new Federal commander in Northern Virginia

Things also looked poorly at sea, despite the natural advantages of the North. The Federal Navy was having a difficult time blockading the vast Columbian shoreline. Even now the policy of ‘port closure’ was proving difficult as several British and French vessels refused to be boarded. Throughout late summer and early fall tensions rose on the high seas.

With much of the West still locked in resolute neutrality, it was proving difficult to truly grapple with the Southern foe. The president called for a ‘bold stroke’ to be planned an unleashed against the rebels. A number of plans were proposed, ranging from a naval invasion of New Orleans to invading Kentucky, violating that state’s neutral borders. Anything or anything that would strike at the increasingly untied Columbian foe.

All these plans would take time, however, and the establishment of Federal naval supremacy. The President needed a victory now to raise the already flagging political morale of the North. Jackson needed to put on a show of Northern ability and victory. He found his stage in northwest Virginia, a land divided against it itself, a microcosm of America.

This distant and remote region of Virginia had always been a land apart. The plantation style economy of cotton and tobacco had never taken root in the rocky mountainous soil. Instead it was a land of smallhold farmers, living subsistence lifestyles among the hills. Politically, it was divorced completely from the rich and powerful lowlands. Virginia spent little money on the distant western portions of the state, leaving it road-poor. As recently as 1829, Virginia had voted on a new Constitution, which had advantaged the slave holding regions of the state. Not one county ‘past the mountains’ had affirmed it and its passage had led to bitter feelings on all sides.

The Nullification crisis had only deepened the divide. The poor white farmers of northwest Virginia cared little for the issues of tariffs, Federal occupation of South Carolina or slavery. If anything, they saw these as blows against a planter aristocracy by the eternal friend of the downtrodden, President Jackson. When war had broken out, the mountain counties had refused to answer the call, and any Columbian agent in the hills was marked for violence.

Still, it was a vital region. Not only was it a part of the cherished ‘Old Dominion’, northwest Virginia was a mineral rich region that allowed access to key Northern areas such increasingly industrial Pittsburgh and the vital trade route of the Ohio River valley. Holding those mountainous regions was key, regardless of the feelings of the locals and the forbidding landscape.

Columbia had few forces to spare, even in these early heady days, and a post in the wild backcountry full of rebels was not a highly desired post. It was assigned to Richard Call, a veteran of the war of 1812 and once a Jackson ally. Like so many, he had turned to the Whigs after Jackson’s occupation of South Carolina and third term nomination. A wealthy plantation owner and slaveholder, he seemed the picture of Southron nobility as he took his small force into the ridges and valleys of northwest Virginia, even as the Battle of Dumfries raged to the east.

He found a land in chaos. The local government had broken down, men were in arms, roads unsafe. Fields lay untended, mines closed, and no official was safe. With backing from Richmond, and later Columbia, Call took harsh measures against these rebels. Arrests without trial, unprovoked search and seizure and a general call for martial law in the mountain counties restored some order, but only increased the hostile feelings in the territory. It was this powder-keg President Jackson saw as an opportunity.

He sent a force under Edmund P. Gaines, a valiant and aged veteran of the the war of 1812 and various Indian conflicts. As with so many schemes of Jackson, Gaines’ appointment served another purpose. The esteemed general was a harsh critic of Jackson, despite staying loyal to the North. For years he had been a thorn in the side of the President, as well as of Winfield Scott, now the most powerful man in the army. Gaines had long considered himself more fit for the post then Scott and had let the nation know it. Sending him to northwest Virginia was as good a way as any to remove him from the political scene.

Edmund P. Gaines, foe of both President Jackson and Commander Winfeld Scott

Still, Gaines was a competent commander and despite the small force given to him, he soon began to make inroads. Entering the state in September, he moved fast through the rough terrain, hoping to secure good lodgings before winter came. He and his men fought a sharp action against local Columbian forces at Clarksburg, forcing the Southrons back, and then again at the Battle of Bickle Knob where Gaines frequently exposed himself to enemy fire.

It was soon revealed Gaines had not only a talent for leading his men through mazes of mountains and forests, but also of recruiting locals to his cause. The rebelling Virginians rallied to his flag, providing not only the food and fodder he needed, but priceless intelligence and talented guides. While Washington, D.C. disapproved of such widespread use of Southerners and arming them (Gaines would face a court-martial over disobeying orders to cease and desist), it was the use of local guides that allowed him to overcome Columbian General Call at Gauley River, where he neatly outflanked the Columbians and forced them in disarray against the river.

Gaines had won the victory Jackson had sought, and as the leaves fell Federal forces controlled most of northwest Virginia. Ever mindful of his local allies, Gaines advocated setting up a new state carved out of enemy territory named Kanawha, after a prominent river. He had the support of a ramshackle assembly that met in October at Wheeling. The assembly advocated for a ‘new and vigorous’ state to be formed under the protection of Federal forces. Despite Gaines’ support, however, the movement faltered when Congress and Jackson, in a rare moment of agreement, turned the offer down, saying that it would give too much credence to the Virginian secession.

One of the early proposals for the new state of Kanawha

While this disappointed the locals, it still left Gaines (and the North) in solid control of northwest Virginia and eyes towards the South.

Why not? In OTL they created West Virginia, no?

A few reasons...

1. Less time for West Virginia to be way behind Virginia in development. The gap is not so big as in OTL so not so 'obvious' an answer. In OTL calls for a independent WV had been going for for a few decades. they have just begun here.

2. Jackson and Scott don't want to back Gaines at all, doubly so in him making new states. There is some personal issues here.

3. Congress is less united here and are convinced the war will end soon. Splitting WV off makes Virginia look like it is a real entity. If you think all of it will be back together next spring, why bother going through all that hassle?

Any of that make sense?

Its back! This was a great update, and I enjoyed reading it. Nice to see some theaters of the war going well for the US, although I still suspect Columbia manages to secure its independence in this TL. Can't wait for the next update.

Its back! This was a great update, and I enjoyed reading it. Nice to see some theaters of the war going well for the US, although I still suspect Columbia manages to secure its independence in this TL. Can't wait for the next update.

I suspect that too, though Andrew will put up a fight.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: