Chapter 3:

La Decena Patriótica, The Ten Patriotic Days

Artistic Depiction of the March of Loyalty. Mexicans joining Madero to defend democracy in Mexico.

(Image Credit C)

The Not So Patriotic Conspiracy and Background

In 1912 Mondragon was busy establishing his government backed arms company when he got an invitation to Cuba to meet some shady figures for fishy business and some cigars. There were already rumors of embezzling funds and his anti-Madero views were not a secret. However, he found himself with Porfirio Diaz aficionados such as General Gregorio Ruiz and Mexican capitalist Cecilio Ocon in Habana, Cuba. The conspiracy also would involve Henry Lane Wilson, the US ambassador to Mexico though he was not present at that meeting for he was too busy trying to convince business men and well to do lawmakers in Mexico City to jump on the Anti-Madero bandwagon. Some unsubstantiated rumors also claimed that he on occasion engaged in some diplomatic work, apparently people expected him to do that stuff for some reason.

The conspiracy’s goals were to free generals Felix Diaz and Bernado Reyes, capture the national palace, force Madero to resign and place General Victoriano Huerta in charge as a sort of “Porfirio Diaz 2.0”. Manuel Mondragon for his part, was reluctant to participate as he has found interests that temporarily aligned with Madero. Before being appointed by Madero to head Armamex, he was already conspiring to place his name on his inventions, skim a less than honest profit out of them, and continue his corrupt ways. Fascinatingly enough, Madero gave him a more legitimate way to achieve most of those goals through Armamex. He gave his co-conspirators support but claimed he would be better off assisting from a distance, in reality he wanted to see which way the wind would blow before setting sail to join the conspirators in what could be either a successful coup or a disastrous act of high treason. [1]

Victoriano Huerta, for his part, felt that it was too soon to act given that each rebellion was put down rather rapidly except for Orosco’s rebellion which he was assigned to fight. By January, with the aid of General Villa, Huerta was able to defeat the last of Orosco’s forces and began making his way with his most loyal men to Mexico City to “celibrate” the victory. Pancho Villa’s mustache must have sensed his true intentions for he wired Madero a message that he felt that “General Huerta’s motivations for defeating Orosco have less to do with loyalty to El Presidente and more to do with his distaste of the new path our nation is taking for the better. It would be best to view him with great suspicion”. Villa’s mustache was not alone, as many in Mexico picked up on the coming coup attempt and sent their own warnings to Madero, who immediately did nothing.

Madero didn’t simply just do nothing, but rather he did everything he could to stall any investigations into suspected plots against his government. Once again, Puebla serves as an excellent case study on Madero’s inexplicable naiveté. Several rumors and chatter were intercepted by various Madero loyalists since 1911, however it wasn’t till 1912 that a more clear conspiracy was discovered. Murcio Martinez and his two sons, Mariano and Marco Antonio, were suspected ring leaders in a plot to overthrow the state government. Murcio Martinez was a general, and Puebla’s former governor, that nearly got caught up in the aftermath of Felix Diaz’s rebellion. He managed to distance himself from Diaz just enough to avoid being accused of aiding that general in his rebellion. Martinez was aware of the plot being hatched against Maduro, and him along with others in other states were preparing to move against Madero’s people.

Emiliano Zapata, much like Pancho Villa, was aware of the dangers and sent one of his men, Abraham Martinez, to Puebla to deal with the conspiracy there. Once he found sufficient evidence he had several former and current state officials, the former governor and his sons arrested. Governor Cañete was caught of guard, while he did authorize an inquiry to the conspiracy he was not aware of Abraham Martinez’s mission and feared that such brazen actions would ignite tensions leading violence had several of those arrested released on house arrest. There was considerable confusion and a breakdown of communication that prevented Cañete from receiving the authorization from Mexico City by way of Emilio Vazquez Gomez. After several meetings, and contentious public arguments, an official state investiagation was launched which resulted in the arrest of Murcio Martinez. Murcio Martinez had friends, Porfirista holdouts, in the Judiciary which managed to get him and his sons released on technicalities.

Prior to his second arrest, renewed strikes in the neighbooring state fueled further tensions between workers and managers in Puebla as well as frustrated rural workers in the country side. A skirmish between federal troops of the 29th battalion led by Aureliano Blanquet and local state militia over what Blanquet claimed was a “mistake”. According to his report, Blanquet received tips on the presence of a rural bandit gang and proceeded to apprehend them. It turns out that this gang was actually a group of revolutionaries moving weapons out of state in violation of the ban of providing support to any movement outside of the state. At this point Madero had to intervene before the situation got out of hand. Considering that Blanquet did have cause to at least detain the revolutionaires for contraband, he sided with Blanquet and called for reconciliation between both sides. He also had Murcio Martinez rereleased as a show of good faith. Problem is, that the good faith favored the conservatives leaving Madero with a negative image among his supporters. In an attempt to salvage his popularity with his base, Madero had Cañete appoint Camerino Z Mendoza, the local militia leader, as the head of the State’s forces and gave him a rank within the federal army.

In other states, liberals had better luck at taking down conspirators however Puebla was not the only state where the conservatives managed to slip away. Murcio Martinez ended up working with Blanquet in the aftermath of the Ten Patriotic Days to launch a coup against Cañete engulfing the state into conflict.

The First Patriotic Day

Madero and his supporters marching to the National Palace to deal with the Coup Attempt.

(image credit A)

In February 9, 1913 very early in the morning led by several anti-Madero instructors and officers, a force of military cadets stormed the prison holding General Diaz and then moved on to free Reyes. By 7:30 AM the force began making its way towards the national palace. General Lauro Villar saw their approach and sounded the alarm. The ensuing battle injured over a dozen people including General Diaz and the Secretary of War Angel Garcia Peña. As the fighting dwindled down, Madero was alerted to the attack and that this was part of a plot to overthrow his government. He began the March of Loyalty (La Marcha de Leatad), the name of his trek on foot from his residence in Chapultepec Castle to the National Palace. During his march he was joined, ironically if one thinks of the march’s name, by Victoriano Huerta. [2]

Upon arriving to the National Palace Madero found that several military and paramilitary units have also taken up arms against him including some units stationed near Mexico City. He immediately made a call to nearby bases still loyal to the president for reinforcements and had Lauro Villar take command of the conflict with aid from general Huerta and his men. As for the conspirators, they took a large weapons depot in the city called the Ciudadela and for the moment beyond a few skirmishes the fighting did not continue for the rest of that day or February 10th.

The Second Patriotic Day

During the second Patriotic Day on February 10th Huerta wanted General Gregorio Ruiz, who was captured after being left behind by retreating anti-Madero forces during the fighting, executed out fear that he would mention Huerta’s treason. Villar refused the order so Huerta went over Villar’s head and spoke directly to Madero which lead to a confrontation between Villar and Huerta in Madero’s office that led nowhere. The point was moot as Ruiz ended up dying before he could either be questioned or executed.

Later that day, general Auriliano Blanquet arrived from Toluca with reinforcements of over 1200 men who quickly turned on Madero tying down the president’s forces in the city spreading the violence beyond the Ciudadela. Emiliano Zapata also wired offering his own men to support Madero, but Huerta managed to convince Madero that Zapata couldn’t be trusted claiming that Zapata would just as soon join Reyes. Villar wasn’t keen on arguing that point, but he felt that Huerta had other motives in mind so he decided to contact Villa who shared with him his concerns regarding Huerta’s loyalties which fell on death ears when brought to Madero who was also hearing claims from others in his administration that Huerta was less than honest and potentially involved in the coup.

In the Meantime, Huerta was busy chatting up ambassador Wilson who agreed to help him establish a line of communication with Reyes in order to coordinate their treasonous efforts. They hatched a plan to make Madero look inept, which would give Wilson ammo to use in order to delegitimize Madero before the other ambassadors, the legislature, the Mexican press, and the US.

The Third Patriotic Day

In the morning of February 11th, Villar began a counter attack in an attempt to dislodge the rebels from the Ciudadela. Huerta had some of his men turn sides and attack Villar’s forces at key positions while sending loyal troops down prearranged areas to be blown up by artillery fire from the Ciudadela. The blood bath forced Villar to stop the attack and retreat. The rebels took the opportunity to venture out of the Ciudadela and gain control of the neighboring areas under the cover of rebel artillery allowing Blanquet’s troops to link up with them. Wilson wasted no time in using the disaster against Madero’s image painting him as an inept leader and claiming that Mexico would be better off without him. He also contacted Washington requesting a naval presence near Veracruz to “insure American citizens’ property and their safety”. That same day, he met up with several other ambassador, mainly those from Spain, Germany, and the UK and began stating that the US was ready to intervene and that Mexico would be better off without Madero in power. Wilson managed to convince the other ambassadors of this using the fears of the fighting spreading and damaging the property of their citizens and putting their citizens in danger.

Madero was approached by several officers who pointed out how the failure had to be the result of a mole, and many believed it to be Huerta himself. Madero failed to trust his people, much to Villar’s annoyance. Villar, for his part, placed Huerta out of field command and tried to put him somewhere where he would not be able to interfere, but Huerta just appealed to Madero who managed to settle a compromise. Huerta would not command his own men but take one of the units from a different command, Villar made sure to pick units staffed by Militiamen from Mexico State that had arrived earlier in the day. The colonels in charge of the militiamen were reluctant to follow many of Huerta’s orders, which led him to complain to Madero whose patience was running thin at the time.

What caused Madero’s impatience was word from the US ambassador who assured him that the US was ready to send in its home fleet with a detachment of Marines to take hold of Mexico’s ports. Wilson was not authorized to provide that sort of information nor was the US government considering any such information, however that didn’t stop Wilson from threatening Madero and assuring his European colleagues that this was the case. [3] Madero had advised Wilson to move to a safer area outside of the city, however fearing that that would place him far from the action he refused. Wilson had set up a small private army in the foreign district of the city which was largely populated by foreigners and he had no intention to be separated from such a group of men.

Wilson sent the following message to DC “There is, however, no doubt in my mind as to the immediate necessity in anticipation of sympathetic outbreaks in Mexican ports that formidable warships supplied with marines should be dispatched to points on the Atlantic and Pacific and that visible activity and alertness should be displayed on the boundary” and in addition requested permission to activity his armed men, which was denied him. However, US warships were dispatched to Mexico’s primary ports which gave credence to his claims of eminent US intervention.

The Fourth Patriotic Day

The rebels managed to make further advances in the city including freeing prisoners form a national prison in the capital forcing Madero to reassign some troops to help bring order. Villar didn’t waste time informing Madero how the enemy seemed to have an unnatural ability to predict the movement of his forces. Madero ordered an investigation to find the mole in his administration and in Villar’s forces. However, Madero would not hear any further theories as to whether or not Huerta was the mole. Emiliano Zapata, upon hearing of the fighting, had ordered Abraham Martinez to link up some of his men with Puebla State Militia and march them to the capital to defend Madero. They arrived around noon providing much needed reinforcements of over 900 men. Zapata had also begun mobilizing his troops and wired other militia leaders such as Pancho Villa, and Victoriano Carranza to do so fearing that the fighting would not be limited to Mexico City.

Wilson had a meeting with several conservative legislators and proposed the destitution of Francisco I. Madero from power. They expressed their willingness to pressure their moderate counterparts in Congress. Soon after these talks, word reached back to Madero of Wilson’s repeated threats. One of these such talks took place between Wilson and Mexico’s Foreign Minister, Pedro Lascurain whom Wilson sought to convince that the best option for both Mexico and Madero was for the president to resign.

The Fifth Patriotic Day

After the rebels captured another key position, a church tower, leading to fierce fighting in that flank. Wilson in the meantime hosted Huerta in his embassy and got in communication with Reyes to develop a plan to finally overthrow Madero. The need for legitimacy was key and the men felt that despite Madero’s support in Congress they could use his setbacks to etch away his support and get the congress to ratify a forced resignation. Wilson wanted to use the threat of intervention as leverage to get reluctant congressmen to fall in line.

However, Villar caught wind of Huerta’s visit with Wilson whose many machinations against Madero were somewhat well known to him. He had Huerta trailed and confronted him. Both men drew weapons and exchanged fire injuring Villar. Huerta quickly made his getaway towards rebel-controlled territory. He was able to go through federal forces as word of his betrayal spread slowly enough for him to make it to the safety of Reyes’ forces.

Madero was shocked and appalled at Huerta’s betrayal, and he was really the only one. Word spread of his “Et Tu Brutus?” moment which was further used to criticize his inability to deal with the situation by his good “friend”, Ambassador Wilson. Unsurprisingly, with the lack of a mole, government forces were finally able to put up a more effective fight and even gained some ground in a few blocks.

The Sixth Patriotic Day

Revolutionaries often relied on the train for quick transportation in the absence of motorized equipment. Depicted here is Emiliano Zapata and his revolutionaries.

(image credit B)

On February 14th, Madero sent Lascurain to meet with the Senate and inform them of Wilson’s threat. Several senators began voicing concerns of Madero’s leadership, causing liberal senators to fire back with accusations of treason. The entire meeting devolved into a shouting match between the different senators. In any event, there was a lack of a quorum, so not much would have accomplished had the Senators been more well behaved. Madero had decided at this point on having a direct communiqué with the US president. In the cable he informed the President of Wilson’s remarks and that “this will cause a conflagration with consequences inconceivably more vast than that which it is desired”.

At this point, Emiliano Zapata had enough, upon hearing of Blanquet’s betrayal and sending word to Puebla to send men to Mexico City he sent orders to mobilize. Zapata had a train commandeered, and loaded it with over one thousand men including state militia, and federal troops still loyal to Madero and headed off to Mexico City. His arrival was fortuitous. Federal troops began loosing ground once again until Zapata’s men arrived. The infusion of fresh troops helped turn the tide pushing the rebels back city block by city block. Zapata was also joined by some cavalrymen courtesy of General Villa who had also just arrived on a similarly commandeered train. Villa decided to go rogue and head to Mexico City after speaking with General Villar. Thanks to the intervention of the two men, the rebels were forced to retreat and abandon the city under the cover of darkness that night.

The Seventh Patriotic Day

After Midnight on February 15th Reyes and Blanquet made their retreat as the fighting died down in the city with plans to head to Puebla and gather support and move on to Veracruz to meet the American reinforcements promised by Ambassador Wilson. The plans however already hit a snag unbeknownst to Reyes and Blanquet. Taft refused to intervene in Mexico primarily because at this point as his presidency was beginning to wind down, he was a lame duck president who didn’t want to get involved in a conflict next door and secondly because he did not see a point to sparking an international conflict over this attempted coup. Wilson failed to get the marines to intervene and Madero had received word from Taft himself of the fact which prompted Madero to send Lascurain to the Senate once more. During the second meeting, Lascurain presented the facts. The coupist rebels were on the retreat, the US intervention was never going to happen, and throughout Mexico militias were being raised proclaiming the defense of Madero’s government securing constitutionalist control of several state capitals.

While Reyes and Blanquet escaped with over 2000 rebels, there were still pockets of resistance in the city. Pancho Villa agreed to move back north to join his main forces which were assembling and waiting for orders in Zacatecas and Chihuahua. Word reached Mexico City that several mid-level military commanders and units from the rurales (Rural local paramilitary forces) in the region were mobilizing against the president. This was a result of Mondragon’s communications during the first few days of the coup attempt. However once Villa and Zapata arrived to Mexico City, Mondragon quickly dropped contact and sent word to Mexico City that he had “reliable sources” that identified the threat throughout the country. He only backed the coup if it meant an easy removal of the president, but feared a protracted conflict that could end in his execution.

The Eighth Patriotic Day

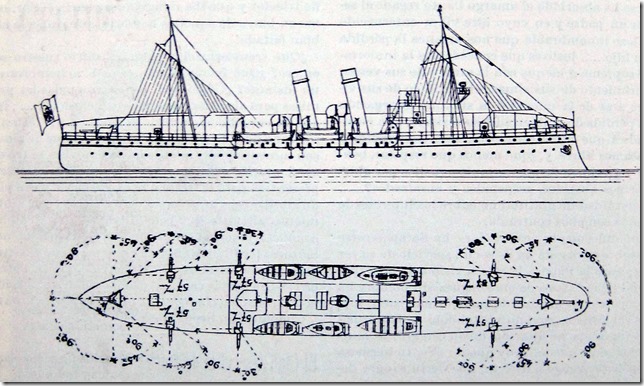

The Mexican Protected Cruiser Tenochtitlan off the coast of Veracruz

(Image Credit E)

Reyes and Blanquet managed to build a strong force in Puebla after skirmishing with government forces but decided to move on to Veracruz in light of a larger armed force coalescing around the city. They had hoped that by taking such a vital port, the US would have to intervene. But Commodore Azueta had prepared his Marines and several hundred-armed sailors and naval cadets for the defense of Veracruz. Azueta also had the support of the army in the area in addition to several bands of militiamen. Based at the port was the protected cruiser ARM Tenochtitlan which was capable of providing moderate artillery support thanks to its 2 prototype Mondragon 8 Inch naval guns which had recently been installed representing the potential might of the Mexican Navy. Though it is important to note that much like the Chamond-Mondragon 75mm canon, the naval gun was designed with the help of an Italian manufacturer.

With Zapata behind Reyes and Blanquet and Azueta Infront of him, Reyes had Blanquet take some of his troops north with aims to make it to Tampico while he would proceed to Veracruz hoping to get Zapata to follow Blanquet. However, Zapata continued to pursue Reyes which led to his defeat later that night. Upon surrendering, Reyes found himself heading back to Mexico City to stand trial for high treason.

The Ninth and Tenth Patriotic Days

Zapata's Calvary Men who helped chase down Reyes and Blanquet

(Image credit D)

Blanquet, upon hearing of Reyes’ defeat and capture, surrendered at around 5AM on February 18th. Zapata had him arrested and transported to Mexico City. For nearly the entire day both Blanquet and Reyes were interrogated to find out how far the conspiracy led. There were still several armed units left in the city but they were quickly being neutralized. While the fighting stopped during the 18th, victory wasn’t declared until the 19th when the President made a public speech before a large crowd at the Zocalo (the central square plaza in front of the national palace). In it he declared that the coup attempt had failed, most conspirators were killed and the others arrested. He also announced the arrest of Cecilio Ocon and had decreed the disarmament of those who opposed his democratically elected government. He also had deputized Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata as well as other independent militia leaders and gave them the task to bring to heel all military units that refused to stand down.

Mondragon managed to avoid accusations of treason, though at this point he was suspected. Reyes had not given him up and Blanquet was mostly ignorant of his involvement. Mondragon pulled out of any further involvement in the conspiracy and decided to keep his head down and count his blessings. However Huerta was still on the loose and had sent him a message stating that if Mondragon was to chicken out, then his involvement would become public knowledge. With that, Mondragon decided to flee Mexico in the coming days but now without calling on all left over Porfiristas to rise against Madero’s government.

The Patriotic Aftermath

The following weeks from late February until mid-April were categorized by outbreaks of countless skirmishes as Zapata, Villar, and Villa began rounding up those who answered Mondragon’s call to arms. The rumors of American intervention leaked and public ire against the US began to boil over. Madero formally labeled Ambassador Wilson a persona non grata and in March the newly inaugurated president Woodrow Wilson complied removing Wilson from Mexico and from his service with the State department all together.

The Navy’s status grew considerably due to their roll in in the Patriotic Ten Days in capturing coupist leaders affording Madero an easy win when requesting a budget increase for the navy and Manuel Azueta was given the rank of Admiral. Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata became rock stars, their popularity rivaled that of Miguel Hidalgo and Ignacio Allende as they were labeled by the people as the saviors of democracy. The two men agreed to work with Madero in reorganizing the Rurales and the federal Army, and putting down units that refused to comply. Several generals and colonels of the federal army who sat on the sidelines throughout the coup attempt began picking sides. Many of them sided with Huerta. The most violent phase of the revolution had begun, and Mexicans everywhere were picking sides. The fiercest battles would last for nearly two years leading to the suspension of presidential elections in favor of electing a constituent congress to write a new constitution in 1915.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[1] The US ambassador in the OTL was actively aware of and supportive of the plot to overthrow Madero. In the OTL Villar was injured during the march which means he wasn’t in command. Butterflies prevented that which, along with the stronger position Madero finds himself in, will prevent his OTL’s fate…execution.

[2] In the OTL, the 29th Battalion was involved in open fighting with a rebel force during a small uprising in Tlaxcala. This happened around the same time that the legal business with Murcio Martinez took place. Madero’s conciliatory actions were much stupider than in TTL. He basically gave all the conservatives a “get out of jail” card and honored the 29th Battalion.

[3] Wilson literally threatened Madero with intervention, a threat he made up.

Image Credits

A: Wikipedia

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MaderoArrivesDecenaTragica.JPG

B: El Universal

https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/cult...ran-documentos-ineditos-sobre-emiliano-zapata

C: Newsweek Mexico

https://newsweekespanol.com/2019/11/la-revolucion-mexicana-que-no-lo-fue/

D:

https://sanquentinnews.com/el-legado-de-la-revolucion-mexicana/

E: Original Image from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/...Bild-23-61-10,_Schulschiff_"SMS_Hansa_II".jpg (I added the Mexican flag)