“Looking across the water, I could make out several structures situated on the coastline. A pagoda was the tallest structure among them, the rest being a collection of humble abodes that would not look out of place on the banks of the Marne. Several small boats gracefully glided across the water as fisherman cast their nets and waited. A larger boat, some would call it a cross between a junk and a skiff, slowly plied its way towards us, no doubt carrying the highest-ranked noble in the area to receive us.

It was really nothing special, I’m sure that if I had another 6 months under my belt, I would’ve found it the most ordinary thing in the world. Yet, as a starry-eyed 20 year old who had never even left Vitry-le-François before joining the navy and the allure of adventure literally in front of my eyes, it was only inevitable that I would say something stupid like ‘Wow, this really isn’t France anymore, huh?’.

The captain stared ahead, a veteran of the Tonkin campaigns and a former adventurer throughout the Far East. He looked at the desolate marshes and the quiet and quaint homes that dotted the landscape, a far cry from the bustling streets of Shanghai or the pagodas of Saigon filled to the brim with people. He spit out his tobacco.

‘It ain’t Hong Kong too, that’s for sure!’ “

Canton is Calling! Adventures of a sailor in China – Jean-Xavier Duchemin, 1934

La Tour de Lai-Chaou looming in the distance

The steamboat Yun-nan moored at Fort Bayard

Neglect and disdain: (1898 – 1909)

The beginnings of the colony

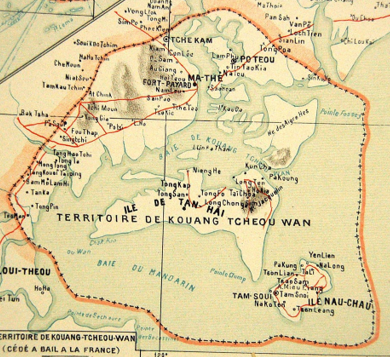

From the beginning, Kwangchow Wan had been an afterthought, for both the Chinese and the French. Its entire existence was owed to the fact that the French were quite susceptible to FOMO: seeing the European seizures of Chinese ports such as Port Arthur, Qingdao, and Weihaiwei, Paris had felt left out and set out to wrestle itself a concession port.

Seeing Japan succeed in where they failed before—taking Taiwan—Paris endeavored to conquer another major Chinese island: Hainan. However, just like they would be at Fashoda, the French were stopped by the British, who were wary of having France take a major, strategic island so close to Hong Kong. So instead, they turned to Kwangchow Wan.

Why Kwangchow Wan? Two main reasons: 1) In either 1661 or 1701, the French East India Company ship

L’Amphitrite ran aground on the shores of what would become Kwangchow Wan. Being forced to spend a significant amount of time waiting for rescue, the crew ventured onto land and were “dazzled by the peninsular microclimates, the depth of the water and the narrowness of the channel” [1]. As a result, they drew up maps of the area and the surrounding seas. These maps and their stories languished in the back of some Navy archive for centuries until 1898. 2) The French wanted another outpost to strengthen their stronghold on Southern China, with their growing economic presence in the region and a series of postal and mining concessions in the region.

Thus, on 22 April 1897, aboard the cruiser

Jean Bart, Contre-amiral Gigault de la Bédollière took control of Kwangchow Wan with little resistance and raised the tricolor above an abandoned port. It would take a year for French diplomats to iron out the “Treaty of the Ceding of Kwangchow Wan”. In it, Qing China would lease the territory out to France for 99 years.

A panorama of Fort Bayard, with sampans and fishing boats in the foreground

Initial anti-French sentiments and resistance

This year would not pass by quietly; armed resistance towards the French would be fomented by a series of secret societies whose goal was the expulsion of the French and local gentry who were loathed for serving the French. Hit-and-run tactics were employed by the local rebels, which in response led to several punitive expeditions. These guerilla actions and retaliatory expeditions resulted in the deaths of dozens of Chinese fighters and civilians and the complete destruction of the village of Vong-Luock.

Resistance to the French would not cease with the formal ceding of Kwangchow Wan to the French. Just days after the signing of the 1898 treaty, a Chinese bureaucrat who acceded to the treaty was assassinated. Local mandarins were wary with collaborating with the French; almost all of the original mandarins who were in the territory in 1898 and collaborated with the French had been assassinated by 1905. The local population was wary of associating with the French; volunteers for the 1er Companie de Tirailleur Chinois were almost non-existent and almost no children were enrolled in the first Jesuit schools of the territory. Locals were unwilling to deal with colonial forces unless a local mandarin/official was with them (more often than not just to see who was brave enough to collaborate and to designate them for assassination later). Two separate societies, one Chinese and one French, soon evolved from the locals’ cool disdain and the occupiers’ sense of racial superiority.

Resistance notwithstanding, the French set about trying to turn this alien outpost into something more manageable. On their initial to-do list were the following: 1) establish political control over the territory, 2) establish a naval port from which to project control over Southern China, 3) turn a profit.

Political foundations of early Kwangchow Wan

For the first point, the French demolished the village of Matché to make way for a new administrative center, Fort-Bayard. A cathedral, officers’ quarters, barracks, and a post office would soon be erected, as well as a branch of the Bank of Indochina. Just opposite these new buildings would be the main port. A rudimentary set of quais would be constructed, and soon a fleet of sampans, junks, and other assorted boats would be docked alongside the occasional protected cruiser and pre-dreadnought. An assortment of naval installations would be built around the newly minted port. Warehouses, arsenals, additional piers, hospitals, coastal defense batteries, and training facilities were among the various buildings built along the port.

Les quais de Fort-Bayard

After the infrastructure came the bureaucracy. Into these new administrative buildings came a cadre of colonial bureaucrats, mainly imported from Indochina. These early administrators soon set up the template for colonial governance for the next couple of decades. A two-tiered justice system was set up where the French would be governed according to French laws and the Chinese would be governed by Chinese laws. This system, combined with racial prejudice, led to conditions that alienated the local population and made governing the territory exponentially harder. For example, the police were free to prosecute locals without judicial oversight and were more than likely to impose heavy fines and punishments. Innocent people would often been scapegoated for real criminals who were rich enough to bribe colonial administrators, who were more often than not interested more in profit than justice. Punishments were noticeably harsh, even by Indochinese standards, and even some seasoned colonial bureaucrats became disheartened by the heavy-handed approach the authorities had in ruling Kwangchow Wan.

Another source of friction between the local population and the colonial administration was the tax system. As said earlier, the French were mainly concerned with squeezing every possible penny from the population, with no regard for inter-community relations and the future of the colony. Thus, we get to a point where “every Chinese man between the ages of 16-40 was held responsible for public works for four days a month; failing which he had to pay 0.4 dollars to the French State.” [1] The onerous taxation system combined with an unjust justice system would lead to the underdevelopment of the colony, as most locals were incentivized to interact with the French as little as possible and possible immigrants were quickly dissuaded by stories of the tyrannical French.

Early economic developments

But while the Chinese community stagnated economically due to anti-French sentiment, the French themselves would kickstart their own economy. The navy would be a big stimulator of demand in the initial days of Kwangchow Wan. With the French Far East Squadron regularly making stopovers in Kwangchow Wan, French sailors and marines would soon be regular customers in the bars, casinos, and brothels that would crowd the Rue des Pecheurs. This early engine of economic activity would help to somewhat ease the tensions between the locals and the French and would help restart the economy that was put on halt during the initial occupation. With French piastres circulating around local hands and a horde of hungry, horny, and curious men, locals got used to the unshaven and dirty foreign devils strutting around in Kwangchow Wan.

Another avenue the French tried to exploit was mining the abundant natural resources around the area. They had been conceded mining rights in the nearby provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi and set out to exploit them. Several expeditions set out into the neighboring Leitchou Peninsula but were soon halted by bands of bandits and other anti-French resistors. Railway workers were shot at and mining camps were raided. Soon, the French gave up these expeditions and retreated behind the walls of Kwangchow Wan. It would take several more years and changes in local attitudes and colonial administration until the French ventured out of Kwangchow Wan.

Other industries in the early days of Kwangchow Wan included fishing, whaling, hunting, and barter trade with the neighboring Chinese villages. These commercial activities were located mainly on the other side of Fort-Bayard, in the village of Po-teou, which would soon be renamed to Poitou after the French region. The port was declared a free port in 1902, which helped somewhat to increase the amount of traffic going through Port-Bayard. A lighthouse was built in 1904 to help support the port’s burgeoning traffic.

A whale caught by the sampaniers of Kwangchow Wan. Oil factories exploiting the local whale population sprung up in the growing industrial area of Poitou

The territory’s lighthouse in 1905

But perhaps the biggest driver of the local economy in the early days was the opium trade and smuggling. Despite the French’s best efforts, poppy and people would become the territory’s most profitable exports.

Illicit trading and blind eyes

In the early days of Kwangchow Wan, the opium merchants held huge sway over the territory. With their connections with networks in Hong Kong and Macao, they were opulent, well-connected, and hard to take down. The opium that they dealt in was highly treasured, and despite the efforts of some bureaucrats, flowed freely throughout the economy. This was because the French ruled the colony indirectly; the colonial administrators relied heavily on local nobles and mandarins to keep order, and these middlemen were very involved in businesses like opium and smuggling.

These opium merchants and colonial middlemen worked together to profit off the opium trade, and also ran many of the brothels, opium dens, and bars in Kwangchow Wan. This allowed them to foster a symbiotic relationship with the administrators; the French would protect their business operations (aka stop other local rivals from rising to prominence in the opium/human trade) and in return they would give the French a healthy percentage of their profits. The French turned a blind eye to the trade because it helped to cover the administrative costs of running an otherwise unprofitable colony. A branch of the Bank of Indochina would soon be established to help manage the copious amount of piastres being generated by the drug trade.

Kwangchow Wan generated an absurd amount of opium: it is estimated that by 1908, almost 50% of the opium seized in Hong Kong came from Kwangchow Wan. In addition, around 15% of the opium market in Indochina belonged to Kwangchow Wan. Around 30% of Kwangchow Wan’s population at this time were opium users. The opium produced by Kwangchow Wan would be shipped to either Haiphong or Hong Kong, and from there would be distributed throughout SE Asia, with destinations including Shanghai, Ningbo, Manila, Singapore, and even the United States. Opium dens even started popping up all the way in France, where local newspapers would lament the large volume of opium inundating Parisian streets and ruining countless lives.

Another favored set of illicit goods that passed through the territory were people. Human trafficking, traditionally a very profitable industry, continued to flourish, as the triads and

gongsi profited from the French turning a blind eye. Kwangchow Wan was a common starting point for people looking to be smuggled into the US, and countless others were sent throughout SE Asia to be sold as servants and slaves. Like opium, this trade was immensely profitable and the French were eager to overlook it for a cut of the profits.

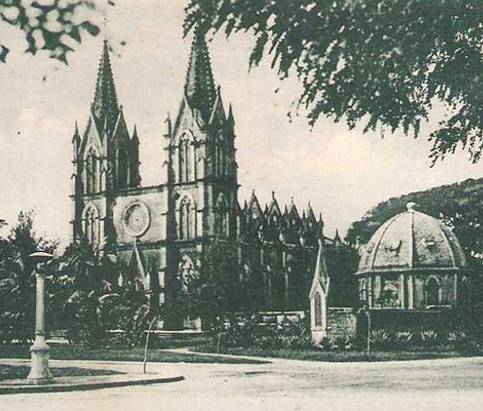

The church in Kwangchow Wan

Unlike the colonial administrators, the church in Kwangchow Wan genuinely tried to improve the lives of whom they served. Several Jesuit schools were established, teaching the rosary and the French language. Seeing the abject poverty many of their students lived in, the head priest of the territory and the sisters of the convent endeavored to make a difference in the colony. The main school, later named after Albert Sarraut, would offer a free meal every day to the students who attended. As more students enrolled, vocational classes were established that would try to teach students valuable skills, such as carpentry and sewing.

Soon, a small textile factory would be established on the grounds of the church, churning out shirts and pants and staffed by women who were fairly compensated and were free from the physical abuse that permeated the other factories in the territory.

Slowly but surely, these efforts would help to thaw the divide between the French and the Chinese and helped spread the French language throughout the territory. The church was an important, and probably the only, source of soft power the French had in the territory.

Piracy, banditry, and continued resistance

One reason why the French decided on Kwangchow Wan was to combat the rampant piracy that permeated the region’s ports. Pirates sailing from Hainan and Guangdong would regularly raid and harass ships plying the Haiphong-Hong Kong or Haiphong-Manila routes. Kwangchow Wan was one of the major bases that pirates would station in, and it was hoped that a naval presence would help curb piracy in the area.

The stationing of naval assets in the territory did help with suppressing piracy, but the inability for French units to scour the surrounding areas plus an underfunding of the indigenous guard meant that piracy would continue to be a threat to local shipping for some time. In addition, the pirates simply retreated into the interior of the country or moved to even more illusive bases on the coasts of Hainan and Guangdong, making them harder to catch.

A trio of pirates awaiting execution, 1903-05

Another issue Kwangchow Wan had to contend with was the continuing resistance to French rule and bandits that would regularly raid the territory. While resistance was not as stubborn by the end of the 1900s as it was in the beginning, the locals would regularly harbor criminals on the run and would underreport taxable income. Collaboration with the police was far and few between and even the indigenous regiments were not trusted by administrators to carry out their duties.

Bandits would regularly target the territory, either harassing economic installations such as mines, farms, and warehouses, or extorting the population through a series of violent raids. The authorities often either did not have the means to respond to these raids or didn’t care as the same bandits were the ones lining the pocketbooks of the authorities through the opium trade. An episode recorded in the newspaper

L’avenir du Tonkin from 1905 illustrates the powerlessness French authorities had with dealing with such banditry.

“On the 8th of February, at 18h30, about twenty pirates burst into the home of a local bureaucrat. They found the man seated at the dinner table with his family, and proceeded to kill the wife, one of the children, and several injured the man and his surviving children. The man, gravely injured and bleeding, ran to the home of M. Champestève (a gendarme) for assistance. The brigands were able to escape and when the gendamerie arrived, armed, they tragically only found the body of the man’s wife and one of his children.”

“Left behind were several cords that were to be used to haul a safe where the victim hid his money.”

“The population is terrified, justly so if we consider the time and place it was committed. This crime, of an unheard audacity, happened very close to the Chinese commercial quarter and to the home of M. Champestève. The Chinese are appalled by this affair, which has considerably damaged our prestige.”

“So what could we do to stop this? M. Champestève, representing himself and the Chinese, thus wrote to the administration asking him for rifles and cartridges for which to permit the organization of a police force charged with the protection of homes from the landing area (of the port) to the mission. This demand was received easily, even with thanks. You would think without doubt this is what happened? Oh! Sweet dreams, with little knowledge of the administrative spirit!”

“The demand was returned, sweet and simply. Impossible to accept, it wasn’t even on stamped paper!”

“From then on, everyone armed themselves and protected themselves from any eventuality. Before sleeping, we hole ourselves up like in a fortress, we check the windows and doors and we check our revolvers and rifles.”

“On my part, sleeping on the ground for the first time, head filled with these recent horrors, staying in a house very close to the tragic house, could hardly fall asleep. Involuntarily, I listen to even the slightest noise, oh my faith! In this absolute black, in the middle of this oppressive silence, in this Fort-Bayard deserted and sad like a ruin, I understand that we can spend several bad nights, haunted by nightmares, ever since the 8th of February, in Kwangchow Wan, despite the protective shadow of the French flag!”

“L'insécurité à Kouang-Tchéou-Wan”, Henri Maître [2]

Impressions of a territory

Episodes like this were unfortunately very common in the early history of the territory. Perhaps the most famous incident of violence in the territory is Claude Monet’s unfortunate visit to Kwangchow Wan in 1909.

Claude Monet had been influenced significantly by Japanese art. He had adopted many techniques from ukiyo-e and woodblock prints, and had revolutionized Western art by introducing Japanese philosophy (mainly wabi-sabi and the Japanese

horror pleni) into his paintings. He had built a Japanese bridge in his gardens and had produced a much-loved series of paintings about it, but felt that it was not enough to satiate his curiosities about the Far East.

So, after a visit to Venice in 1908, he organized a trip to the Far East in what would be his most ambitious trip yet. He would have stopovers in Cairo, Aden, Pondichery, Bombay, Singapore, Saigon, Haiphong, Kwangchow Wan, Shanghai, Nagasaki, Hiroshima, Hyogo, and Tokyo. He would get the opportunity to see the world and to record it on canvas, and this trip was highly anticipated by his fellow artists, art dealers, and the general public. He received donations from high society all over the world, and on his departure from Toulon, his chartered ship was escorted out of the harbor by the newest French battleship

République, as a favor from his close friend Prime Minister Clemenceau.

And so off he went, exploring the exotic locales he stopped by in and churned out impressions of all of them. By April 1909, he had made it all the way to Haiphong and Kwangchow Wan lay in his sights. Like most others, Monet had never even heard of Kwangchow Wan until planning his trip, and even then, he only went more out of Kwangchow Wan’s novelty than its artistic worth. When his ship docked in Fort Bayard, he had the opportunity to scout out potential painting spots. Upon seeing the state of the territory—its primitiveness and lack of European influence—he exclaimed,

“Ah, so I shall be the Gauguin for China!”

He would spend around two weeks in the territory, exploring the markets and opium dens of the territory. He would amble down the Rue des Pecheurs and capture the fishmongers, or he would mosey over to the church to capture the Jesuit school in session. A favorite subject of his was the pagoda of Lai-chou, which loomed over the territory like the Eiffel Tower and inspired a set of paintings depicting it at different times of day. He even dabbled in portrait painting, making portraits of several colonial administrators and bureaucrats.

Captain Lao of the 1er regiment des tirailleurs chinois posing for Claude Monet

On the last night of his visit, a painting session was rudely interrupted by a gang of bandits who had heard rumors of a grumpy old Frenchmen who was thought to be of great importance and wealth. Monet himself had ignored the sounds of the bandits breaking into his temporary home and had yelled at the intruders thinking they were local children messing around. When he looked up from his easel to see a group of bandits armed with swords, scimitars, and knives, he was reportedly amused by their strange choice of weaponry and wished to paint them. When his companion politely informed him of the situation, Monet simply sat down and lit his pipe, informing the robbers that they may take anything except for his paints and canvases.

The bandits then set about the room trying to uncover the riches that Monet was rumored to have. When they found nothing but paints, canvases, and other art supplies, they became agitated and started to threaten Monet and his companion. According to his companion, Monet stayed calm and stoic, remarking that they

“could take my life, but they could not take my paintings.” Things came to a head when the ringleader held a sword to Monet’s neck, and it seemed as if the great painter was to meet his end in a colonial backwater. But suddenly, Monet spotted one of the bandits ripping his canvases trying to look for some hidden cache of gold. Greatly enraged by this, he deftly escaped the sword held to his throat and started throwing paints at his assailants. Suddenly confronted with an angry old man screaming at them, a copious amount of paint blinding their eyes, and the gendarmerie bearing down on their location, the bandits had no choice but to high tail it out of there. At the end, the only things that were hurt were a couple of Monet’s paintings and the gendarmerie’s reputation. If they could not protect one of the most famous men in France, how could they possibly protect the average Frenchmen, or even the local Chinese?

As Monet made his way to Japan, news of the encounter slowly filtered back towards Paris. This extraordinary encounter delighted the art community, who immediately started writing dramatizations of it and started planning trips to Kwangchow Wan for the novelty. On the other hand, it embarrassed the government, as it gave the (rightful) impression that the territory was a lawless place that even 10 years under French dominion could not save. Strangely, this episode led to a slight increase in donations and volunteers for

la Coloniale as the many manuscripts, plays, and paintings helped to paint a picture of the exotic lawlessness of Kwangchow Wan that men in their 20s seemed to adore.

The final straw and change in the colony

While this episode was embarrassing for the government, it wasn’t all that serious. What was serious, however, was an incident later in 1909 that would prove to be the catalyst for change in the colony.

In July 1909, just after the hubbub of the Monet incident was slowly dying down, a thousand bandits raided the town of Tong Pin, at the very edge of the territory. Such a brazen attack led to an overreaction from the administration, who summarily executed those in the town suspected of collaborating and forcefully removed the rest of the inhabitants. This led to a rash of attacks on French installations: several arson attacks on European villas, the kidnapping of several European children, and the murder of an important bureaucrat. In response, the head administrator arrested three hundred locals, personally interrogated and tortured them, and left them to die from hungry and thirst. This heavy-handedness was uncovered by a reporter and soon was front page news in Paris. [3]

It led to uncomfortable questions for the government: why was it that Kwangchow Wan was being run so cartoonishly inept and evil? France was supposed to be the civilizing force, yet it was using methods to rule Kwangchow Wan that resembled that of the medieval ages. And why is it that despite all of its efforts, France could still not guarantee the safety of its own citizens in the territory, as shown by the kidnappings and murders of Europeans? Clearly something had to change.

The embarrassment from the Monet affair and the outrage from the Tong-Pin affair made it impossible for Kwangchow Wan to continue in this sordid way. And so, in October 1909, Kwangchow Wan was officially detached from French Indochina and was declared an independent Colony. It would receive some much needed reform in the shape of a new Governor-General, increased funding from home, and new Legislative and Executive Councils.

[1] –

Francophonie and the Orient, Mathilde Kang

[2] – This event really happened, and the original text in French can be read here (

https://www.entreprises-coloniales.fr/inde-indochine/Kouang-tcheou-Wan.pdf)

[3] “State and Smuggling in Modern China: The Case of Guangzhouwan/Zhanjian”, Pieragastini (this episode actually happened in 1904/5)

* Photos mainly sourced from Wikipedia or from

www.entreprises-coloniales.fr