how do you make the maps (program)?The Empire in the 1830s (Part 2 of 2)Portuguese East Africa/Moçambique:

O Império na Década de 1830 (Parte 2 de 2)

The Captaincy of Moçambique was administrated from the island of Moçambique which until 1834 was the capital of Portuguese East Africa but the diminutive size of the island and lack of water together with the need for a more central seat of government made the Portuguese authorities choose Quelimane as the new capital.

Despite the loss of protagonism, the Captaincy of Moçambique managed to achieve the best results of all four in Portuguese East Africa despite the emergence of multiple emirates by the coast that were sponsored by Sultan Saíd Albusaide [Said bin Sultan] of Omã who had designs in the area. These emirates employed guerrilla techniques to prevent the Portuguese from expanding and attacked the town of Angoche multiple times as well as the Portuguese allies of the Kingdom of Maravi/Malauí which showed signs of decadence. Slowly and steadily the Portuguese were able to consolidate most of the coast below the Island of Moçambique and establish secure pathways to the heart of Maravi.

The Captaincies of Quelimane and Sofala were separated by the mighty River Zambeze and the authorities in both of these captaincies converged their strength to control its valley which was vital to the region. Between 1794 and 1802, several droughts and epidemics devastated the valley and the effects lasted until the 1830s with the most significant one being the collapse of the Prazo system since the chicundas (slaves/servants) could barely feed themselves and thus exportations were out of question.

Many chicundas deserted the Prazeiros and turned to banditry, elephant hunting or became mercenaries. However, some Prazeiros were able to increase their power with thousands of chicundas serving as soldiers and creating powerful potentates that could contest the directives sent by the Portuguese Governments.

The Portuguese tried to take advantage of this period of anarchy and were able to control the mouth of the Zambeze and the valley all the way to the decaying town of Sena but to reach the important settlements of Tete and Zumbo further north which they exerted nominal control, they were forced to obtain authorizations from the Prazeiros which was seen as a humiliation.

In 1837, Gonçalo Caetano Pereira, Prazeiro of Macanga and Alves da Silva, Prazeiro de Masanjire decided to join forces and block the Portuguese from reaching Tete to show force to the meddlesome authorities in Quelimane but this only made Governor-General Luíz Miguel Sarmento to start the First Prazo War. After a year of vicious fighting, Sarmento entered the fortified village of Chamo, which was the capital of Masangire, in triumph and forced the Alves da Silva family to flee eastwards.

The passageway to Tete was reopened and the Portuguese victory made António Manuel de Souza, Prazeiro of Gorongoza within the territory of the Captaincy of Sofala join forces with Sarmento but it was not the only reason Souza took this decision because aside from the authorities of Quelimane and the Prazos, a third player entered the scene...

King Soxangana [Soshangana], a relative of the famous Xaca Zulu [Shaka Zulu], expanded the territory of his kingdom from the shores of the River Limpopo to the banks of the River Save which he reached on 1836 after subduing the Tsongas, the Xonas [Shona] and many other tribes whose young men he incorporated into his army and whose women he made into wives of his men. It was the birth of the Gaza Empire named after Soxangana’s grandfather.

Soxangana defeated two other Zulu warlords named Zuánguendaba [Zwangendaba] and Nexaba [Nxaba] and pushed his empire’s borders to the Zambeze valley and which point he became a serious problem for Portugal and the Prazos. A smallpox epidemic cost the King many of his soldiers so he decided to return to Bileni on the banks of the Limpopo and leave his son Muzila [Mzila] to subdue the Zambeze Valley.

António Manuel de Souza judged that an alliance with the authorities of Quelimane was his best course of action but Sarmento’s invasion of Masangano at the end of 1838 that Souza supported was a failure and almost brought some of the other Prazos to Masangano’s side with Sarmento having to bribe Macocolo to keep it away.

Muzila’s raids and frontal attacks against Gorongoza despite the peace treaty between Portugal and the Gaza Empire were stopped by Souza and Sarmento’s forces with the tacit connivence of Gonçalo Caetano Pereira who did not exploit his victory against the Portuguese simply because he feared Muzila would destroy him after he wasted his resources against Portugal. The Portuguese victory pushed the Gaza Empire away from the Zambeze.

The Captaincy of Inhambane was not so lucky with both Inhambane and Lourenço Marques being attacked multiple times by Soxangana and to stop these attacks he demanded a tribute which the Portuguese were forced to pay. Further, any person wishing to pass through the Gaza Empire’s territory had to pay a toll. In 1834 Soxangana mounted a large attack at Inhambane that was repelled with much difficulty by the Portuguese and not to give up, he made yet another attack in 1836 that was also repelled.

After this, Soxangana decided to make peace with the Portuguese and delivered 2 Boer children to Lourenço Marques as a token of goodwill, thinking the terrified children to be Portuguese. The children were Maria de Rensburgo [Maria van Rensburg] of 12 and her brother Pedro de Rensburgo [Piet van Rensburg] of 7, children of João de Rensburgo [Johannes van Rensburg], a Boer leader whose expedition was massacred by Soxangana on July 1836, with only the children being saved by one of the King’s men. Captain João Miguel Serafim accepted the children and settled them in Lourenço Marques, making them the first Boers of Portuguese East Africa.

Just like Guiné, the Lourenço Marques Bay was contested between Portugal and Reino Unido and for this reason, the official settlement of the Espírito Santo Estuary started in 1826. The British tried to kick the Portuguese away without success but they were not the only ones trying this, in 1833 the King of the Zulus, Dingane Senzangacona [Dingane kaSenzagakhona] attacked the settlement likely because he felt the Portuguese were usurping his territory, allying with Soxangana and stealing profit from him.

The Siege of Lourenço Marques began on September 16, 1833, and continued for weeks with Captain Serafim and his garrison withstanding the violent assault and surprising the Zulus with daring night raids. When Inhambane and Quelimane spared some extra troops that arrived in late October, Dingane fearing more losses decided to cease the siege and negotiated with the Portuguese before his political opponents could take advantage of the situation. Thus in exchange for a heavy tribute, the King of the Zulus gave control of the lands to the east of the River Matola to the Portuguese and after a prisoner exchange, peace was made and Lourenço Marques was saved.

About two years later, on April 13, 1838, an expedition of Boers commanded by Luíz Tregarte [Louis Tregardt] arrived at Lourenço Marques after five years of travelling. Like the Rensburgo children, they were well received by the new captain, Manuel Costa who did not want to lose a golden opportunity to increase the white population of the village and the pool of available to fight.

The Boers were given a lot of freedom to build houses, a school and a church as long as they recognized Portugal’s authority. While initially sceptical of accepting such terms, Maria de Rensburgo, then 14, convinced them to accept. They were, however, hit by malaria that cost the lives of about a third of the party, including Tregarte’s wife Marta. Tregarte sent a servant to Natal to request an evacuation by sea but many of the Boers led by Maria and her brother Pedro did not want to leave. Tregarte also succumbed to malaria on October 25 and with his death, Maria’s faction eventually overtook the community and nearly all of the remaining 37 Boers remained in Lourenço Marques.

The Boer school opened up in November 1838 and while many members of the community did not want the Portuguese and the local natives to attend, it allowed them to. While the Boers spoke the Cape Dutch dialect, the more numerous Portuguese soldiers influenced their dialect and most of them learned to speak Portuguese, especially the children. In opposition, the Dutch Calvinist Church managed to convert many soldiers and natives early on despite the local Catholic priest’s attempts to prevent this from happening.

Moçambique was without any doubt the Overseas territory in which the Portuguese struggled the most. It was clear that the 1 500 soldiers were not enough to address all the enemies in the region. The development of the cities and towns was also far below what was witnessed in Angola with only Quelimane, the capital having the most improvements though the Island of Moçambique, Angoche and Inhambane also had considerable improvements.

There were also attempts to improve Tete, Sena and Sofala but they were in such a terrible condition that they were mere carcasses of their past glory, threatened by the Prazos and the Gaza Empire. Lourenço Marques received little help from Quelimane but despite it, it was also improving at its own pace with a whaling company founded in 1818 by American whalers and by the Boers planting the fields.

A diversification of the economy was also noticeable following the same pattern as in Angola meaning increments in the plantation of sugar, tobacco, cocoa and coffee, cattle breeding, ore extraction and fisheries.

The estimates of the white people (including soldiers which represent around half of the total) for the entirety of Moçambique in 1840 are:

Índia Portugueza:

The Estado da Índia was composed of Goa, the most populous and largest of the Indian territories, Damão, Diu, Dadrá and Nagar Aveli as well as the islands of Timor, Solor, Flores and the Macau Peninsula until 1837 when their autonomy was consolidated.

While Cabo Verde was the first colony to be fully integrated into Portugal, the Estado da Índia was the most likely to be next. This, however, was not something supported by the more conservative Deputies and Peers who considered the distance to Lisboa to be a big problem as in the 1830s one still had to sail for about a year to reach Goa. Indian Deputies often missed the Cortes’ sessions due to this.

The integration process, however, started despite the opposition but except for the creation of the Indian branch of the Real Guarda Nacional (RNG) in 1831 the Status Quo remained until 1836 when the first Goan Governor-General was nominated by Saldanha. Bernardo Peres da Silva had already served multiple terms as a Deputy for the Estado da Índia as an Independent although he had links to the Left and was an advocate of more liberties and autonomy to the colonies and for this reason he was received in Goa with great enthusiasm by the local population after his nomination.

Peres da Silva’s goal was to make sure the natives of the Estado da Índia had the same rights as the Europeans which he deemed as the only way the territory could be properly integrated in Portugal. For this reason, he facilitated the access of the natives to the judicial, fiscal and administrative positions that he reorganized; he continued to follow the directives coming from Lisboa such as the extinction of the monastic orders and the sale of their properties, the construction of primary and second schools as well as the Lyceum of Goa and reduced most of the taxes that were exclusive to the native population.

While very beneficial in the long term, Peres da Silva’s measures seriously affected the interests of the Goan aristocracy, especially the metropolitan bureaucratic officials and military commanders. These groups joined forces in a revolt that happened on April 9, 1836, about a month after Peres da Silva’s appointment led by General Joaquim Manuel Correia da Silva e Gama, the most important military commander in the Estado da Índia and a member of Peres da Silva’s Governing Council.

The rebels surrounded the Governor’s Palace in Panjim and eventually entered it, capturing Peres da Silva and forcing him to sail away in humiliation. This, however, caused the people in Panjim to protest and the RNG, essentially made of natives led a counter-revolt against Silva e Gama, starting a brutal urban battle between the two sides.

The soldiers won the battle after six hours but they had suffered considerable casualties and the beaten RNG fled but incited revolts all over the Municipality of Ilhas de Goa which by April 10 was in mutiny and readying a large assault against Panjim. When the revolt started spreading to the other Municipalities of Goa, most of the soldiers from the European contingents that were neutral declared for Peres da Silva and joined the natives in their struggle.

By April 14, the rebels were surrounded by a much larger force of troops, RNG and armed peasants which led most of the soldiers to surrender. Those who kept fighting were overwhelmed and Silva e Gama was captured by Colonel João Cazimiro de Vasconcelos who was appointed Interim Governor until Peres da Silva’s return. Messengers were sent to Lisboa and after the humiliated Governor, who got knowledge of the counter-revolt’s success in Bombaim and immediately returned to Goa where the population was celebrating.

Saldanha in Lisboa was forced by his followers, coalition partners and pragmatism to accept the result of the counter-revolt as he feared that Portuguese Índia could follow Brazil’s footsteps and declare independence, though they Manuel Correia da Silva e Gama to Moçambique with next to no punishments.

Peres da Silva was able to rule without opposition and with the support of the people and Lisboa and until his term ended in 1840, he promulgated many decrees to cease and punish racism and discrimination including against White people born in the Estado da Índia which were often considered lesser individuals to those from Portugal and motivated by the Silva e Gama’s revolt he wanted to get rid of the Portuguese garrison in favour of the RNG but the Government forbid him from doing so and even started distrusting his intentions. He did, however, manage to reduce the garrison’s size by sending troops to Moçambique and Timor to help the local administrations.

His tenure aside from boosting the power of the natives also saw the revitalization of the Portuguese language and culture after many decades of decadence and the immigration of the population to British Índia, namely Bombaim, in search of better opportunities. Literacy rates of the young Luzo-Indians increased thanks to their education in local schools; local newspapers written in Portuguese proliferated; cafes and salons created a new politically engaged population that wanted more representation.

The capital of Estado da Índia moved from what is now called Velha Goa [Old Goa] to Panjim, which was renamed Nova Goa and was 10km to the west of Velha Goa, being the residence of the Governor-General since the end of the last century. All this was due to the serious epidemics of malaria and cholera that caused the death of many Goans and for this reason, led to the creation of the local Medical school that was reformulated in 1840 to become the Goa Medical and Surgical School in the same model as the ones in Lisboa and Porto and would train many doctors to serve the Empire in the following decades.

Economically, agriculture production outputs increased a lot with investments in corn, rice, mangoes and coconuts, a blend of what was happening in Portugal, Africa and Asia. Large deposits of iron and coal were found in the Municipality of Bicholim in late 1839 which were seen as a good way to revitalize the economy and boost trade with Portugal which needed these commodities for its industrialization.

Goa and Damão also developed local textile manufacturers that were initially supplied by cotton coming from British Índia but were progressively replaced by cotton coming from Moçambique which was much cheaper to them. These clothing products were made in Indian fashion to not compete with those produced in Portugal and in a time when the British had euthanized Indian industry, it created economic opportunities.

Timor, Solor, Flores and Macau:

Interest in Timor and its adjacent islands was still linked to the profitable trade of sandalwood and other exotic products to Europe and China, although foreign competition from the British and Dutch was increasing. Considering that Portugal had tacit control and suzerainty over Timor and Flores, as well as the fact that Catholicism and Portuguese creoles were considerably widespread, made Lisboa attempt to exert more control over these islands with minimal costs.

During the 1830s the administration in Díli in the island of Timor was given progressively more autonomy to act. Thus Governor Jozé Maria Marques appointed in 1834 had more room to conduct an autonomous diplomatic policy to further Portugal’s interests while not provoking other Europeans such as the Dutch. In the following years, Maria Marques concluded several treaties with Timorese tribal chiefs to make them vassals of Portugal.

After skirmishes around Larantuca in Flores with troops of the Sultanate of Bima sponsored by the Dutch, the Larantucan topases accepted the presence of a Portuguese garrison. The fear of the Dutch encroachment on the island made the Larantucans act as intermediary agents to place the entire island under at least Portuguese indirect control.

This increased the tensions with the Sultanate of Bima which dominated the western part of Flores and most of the nearby island of Sumbava [Sumbawa] and its overlords, the Dutch. Skirmishes became more common but were usually won by the Portuguese as the Dutch refrained from strengthening Bima so that they could be more easily dominated soon. The Dutch also increased their forces in Western Timor namely in Cupão [Kupang] from where they also sought to make peace and subjugation treaties with the population to counter Portuguese advances.

The hierarchy of Timor and Flores that had been in use since the 16th Century was slightly changed with the Portuguese also called “white Portuguese” by the Dutch at the top, exerting unprecedented control over the population, controlling the foreign politics and trade while having the duty of protecting the population. The topases or “black Portuguese” collected tributes in the name of Portugal and exercised control over the villages and local commerce. This new model guaranteed the interests of both groups, making the control of the islands easier.

Jozé Maria Marques promoted considerable improvements in Díli and Larantuca with the first stone and brick houses, wide streets, fountains, warehouses, churches and schools being built to prevent the usual fires from constantly destroying the towns. To reduce costs in supplying the islands, the cultivation of rice was promoted but the sandalwood still dominated the fields and more profitable cultures such as coffee, cinnamon and cocoa were also being tested to diversify the economy.

Better control over Timor and Flores together with an increase in agriculture outputs allowed the many debts Maria Marques was incurring to be paid and the quality of life of the population namely in Díli and Larantuca increased which contributed to neutralising slavery.

Macau was still the main port through which Europeans could trade with Txingue [Qing] China, thus the small outpost held a huge strategic importance for Portugal who profited from Macau’s customs duties. With the administration’s separation from the Estado da Índia in 1837, the small port became the headquarters of the Captaincy of Macau, Timor and Solor, receiving for the occasion its first Captain-General.

This change in status was not recognized by China, but Portugal did not care. The Leal Senado de Macau which until then ruled the city saw most of its privileges revoked in 1834 and was relegated to a mere Municipal Town Hall with an honorific title subordinated to the Captain-General.

By the 1830s, with the arrival of more troops, Portugal was able to start expanding its influence to the islands surrounding the Macau Peninsula namely Taipa, Coloane, Lapa, Dom João and Montanha without the help of the missionaries that had made their home there without China’s permission, although the Portuguese authorities fearing China’s response did not lay claim or fully occupy the islands.

But at the same time that Portugal was regaining its strength, the British already had enough commercial and military strength to provoke the Chinese. Their intention to sell huge quantities of opium produced in British Índia to the Chinese clashed with the Chinese authorities’ desire to stop such prejudicial and immoral trade.

But after the White Lotus Rebellion (1796-1804) the Txingue [Qing] Dynasty saw its silver reserves deplete and as a consequence the Emperors were forced to increase taxes, especially on Chinese traders who already were overburdened with expenses needed to fight piracy and banditry and this destroyed this important backbone of society. Parallely the Army was in steep decline and outclassed by European troops in everything but their numbers.

Thus the First Opium War began in 1839 between Reino Unido and China and despite British requests, Portugal still considered the Chinese Army a threat so it declared itself neutral but the winds of change were already blowing.

And with this, I finish the Empire Updates. It took a while but I think they came out ok with Portugal expanding almost everywhere except Moçambique where they lost territory. Next chapter will be about the Military and Foreign Policies and then I will finish the decade with what's happening around Europe and Brazil though I hope I don't waste too much time there...

Without further ado, thank you for sparing time reading and I hope everyone has a nice day and stays safe.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Vivam Lusos Valorosos, A Feliz Constituição - A Portuguese Timeline

- Thread starter RedAquilla

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 14 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The Kingdom: 1834 Portuguese Legislative Elections The Kingdom: 1830s (Part 2 of 3) The Kingdom: 1838 Portuguese Legislative Elections The Kingdom: 1830s (Part 3 of 3) The Kingdom: The Economy in the 1830s Overseas: The Empire in the 1830s (Part 1 of 2) Overseas: The Empire in the 1830s (Part 2 of 2) The Kingdom: The Armed Forces and DiplomacyI was seeing if I could have Boers in Angola in this timeframe but I found none, instead, I found about Tregdt and Rensburg's expeditions which used to be the same one until they had different interests and separated with the latter being exterminated by Soxangana except for Rensburg's two children and the former reaching Lourenço Marques. I just changed a couple of things thanks to a slightly more interested and committed Portugal.Very good update , wasnt expecting the boer setlement but is really cool , maybe more could happen in the future , in fact i am curius if a more active portugal in africa will afect the development of south africa in any way.

South Africa will be very different in the long run.

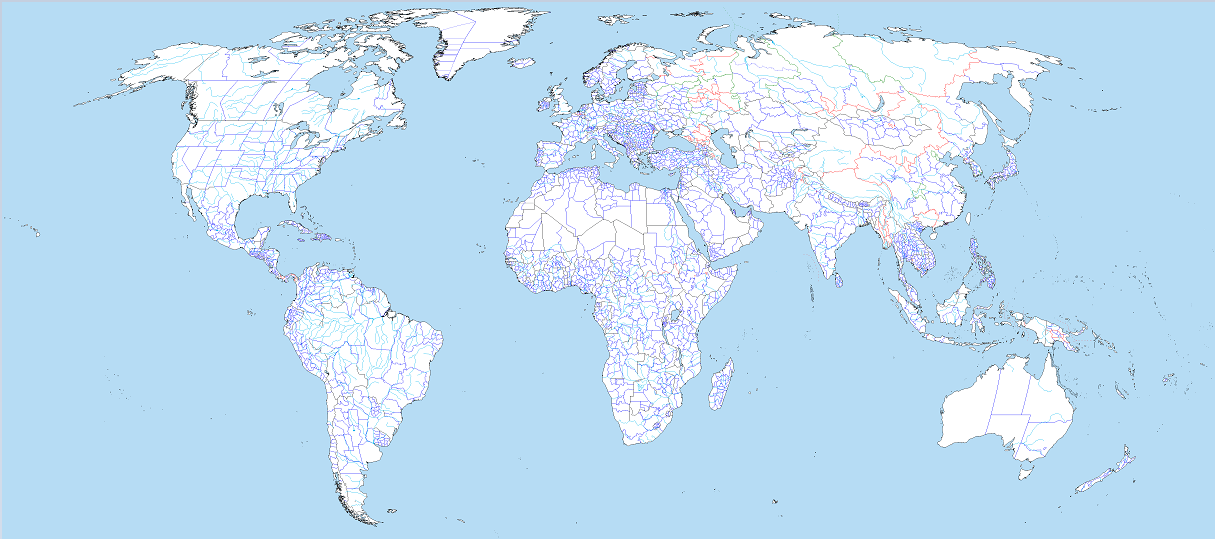

I have no fancy program, I got a big blank map with subdivisions and rivers, then I made a copy without the subdivisions and with references from other maps, I made the borders, painted and wrote the names in MS Paint. I used Victoria 3 colour scheme for Portugal.how do you make the maps (program)?

Can you share it? I randomly make maps for totally ASB scenarios just for fun and have being using the hoi4 one until now.I got a big blank map with subdivisions and rivers, then I made a copy without the subdivisions

Which one do you want? The original one with rivers and subdivisions, the one with just rivers or the one with just subdivisions?Can you share it? I randomly make maps for totally ASB scenarios just for fun and have being using the hoi4 one until now.

@RedAquilla , your stories are awesome!

Really loving this TL, especially the maps, keep it up

Thank you for the kind comments, I will try to have the next update ready soon.Cant wait for the next update

The original one, please.Which one do you want? The original one with rivers and subdivisions, the one with just rivers or the one with just subdivisions?

I have been struggling to upload the image because it's large. See if this link works, I have cut Antarctida from the map...I don't think its needed but if you want it. The borders are "globe-like" so some divisions may seem a bit off.The original one, please.

The Kingdom: The Armed Forces and Diplomacy

Military Policy:

Portugal began the 19th Century with many military commitments due to the state of war that Europe endured at the time. Under these conditions, the size of the Portuguese Army swelled to levels never seen before: in 1807 there were 24 Infantry Regiments, 12 Cavalry Regiments, 4 Artillery Regiments, 48 Militia Regiments, 1 Legion of Light Troops and 24 Ordenança Brigades for a total of about 150 000 soldiers.

Even with so many soldiers, the army’s first engagements after Junô [Junot] was expelled did not achieve the expected results and the astronomical military expenditures were only harming the country’s finances. Things only changed when British Generals such as Artur Uéselei [Arthur Wellesley] and Guilherme Beresforde [William Beresford] began drilling the Portuguese troops in the joint Anglo-Portuguese Army turning subpar troops into one of Europe’s finest due to their capability to properly follow orders and adaptability. Uéselei [Wellesley] himself requested Portuguese troops to fight in the famous Battle of Uáterló [Waterloo] but time did not allow it.

When the European conflicts ceased and Liberalism was implemented in Portugal, the Portuguese Army had its size greatly reduced to keep the military expenditures low since they were the main reason for the country’s Public Debt being so high. This caused some resentment in the Armed Forces with many of its officials sympathizing with the Absolutist cause which they believed was more beneficial for them. Thus it was no surprise that Prince Miguel and later Queen Dowager Carlota Joaquina and the Duke of Cadaval could count with plenty of support in the Armed Forces.

Only when Cadaval’s insurrection was defeated did the situation start to change when many of the Absolutist officials fled abroad in fear of reprisals and officials sympathising with Liberalism became the norm. Despite this change, the Armed Forces were always considered more conservative. The Reforma dos Marechais [Marshals’ Reform] (1828-1832) was the Armed Forces’ first overhauled since 1806-1808. It set the size of the Army to 40 000 soldiers and fixed the Portuguese Regiment size to 2 000 men (1 000 in Cavalry Regiments). Thus the country had:

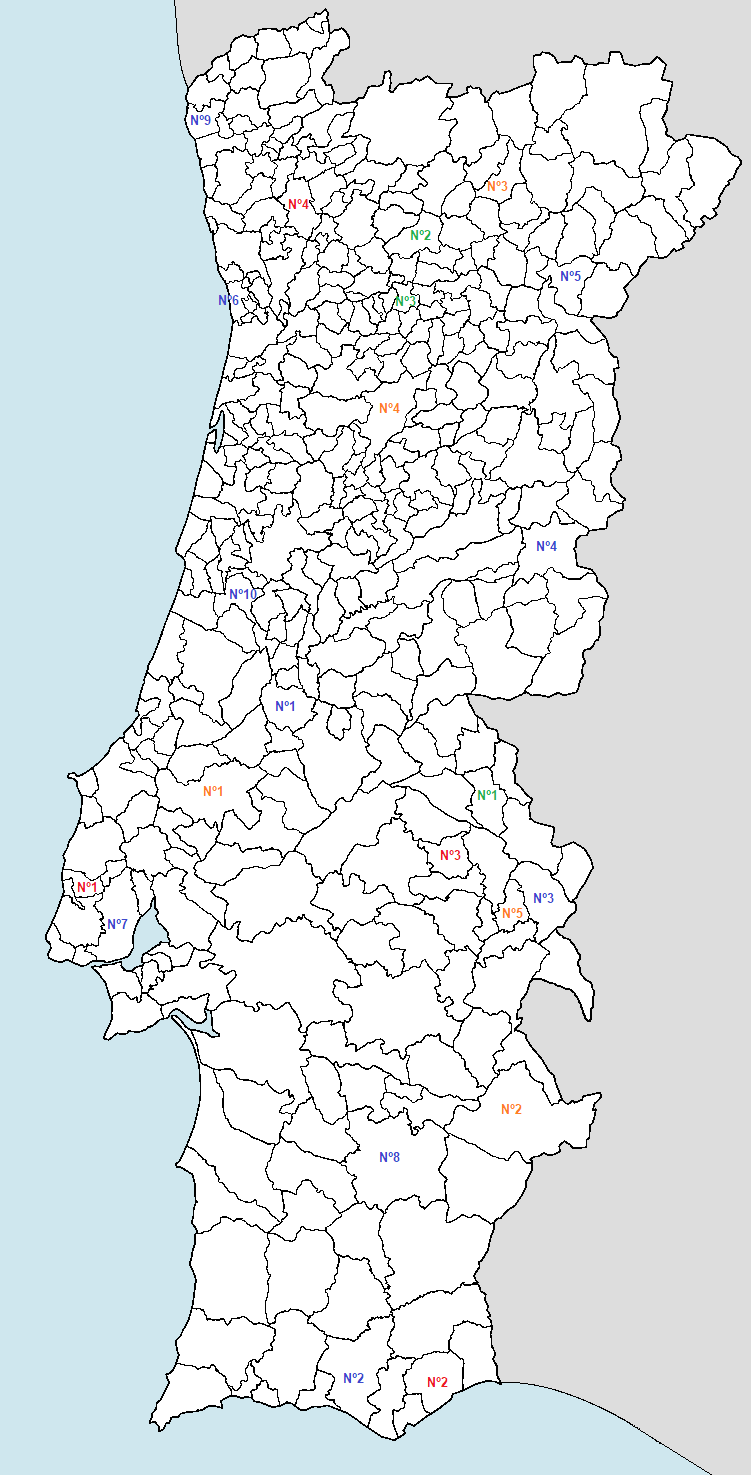

1st Infantry Regiment [Nº1] Tomar (Estremadura)

2nd Infantry Regiment [Nº2] Loulé (Algarve)

3rd Infantry Regiment [Nº3] Elvas (Alto Alentejo)

4th Infantry Regiment [Nº4] Penamacor (Beira Interior)

5th Infantry Regiment [Nº5] Moncorvo (Tráz-os-Montes)

6th Infantry Regiment [Nº6] Porto (Douro Litoral)

7th Infantry Regiment [Nº7] Lisboa (Grande Lisboa)

8th Infantry Regiment [Nº8] Beja (Baixo Alentejo)

9th Infantry Regiment [Nº9] Viana (Minho)

10th Infantry Regiment [Nº10] Soure (Beira Litoral)

1st Caçador Regiment [Nº1] Portalegre (Alto Alentejo)

2nd Caçador Regiment [Nº2] Vila Real (Tráz-os-Montes)

3rd Caçador Regiment [Nº3] Lamego (Beira Central)

1st Cavalry Regiment [Nº1] Santarém (Estremadura)

2nd Cavalry Regiment [Nº2] Moura (Baixo Alentejo)

3rd Cavalry Regiment [Nº3] Valpaços (Tráz-os-Montes)

4th Cavalry Regiment [Nº4] Vizeu (Beira Central)

5th Cavalry Regiment [Nº5] Barbacena (Alto Alentejo)

1st Artillery Regiment [Nº1] Mafra (Grande Lisboa)

2nd Artillery Regiment [Nº2] Tavira (Algarve)

3rd Artillery Regiment [Nº3] Fronteira (Alto Alentejo)

4th Artillery Regiment [Nº4] Guimarães (Minho)

In addition to the regular Army, the Real Guard Nacional (RGN) [Royal National Guard] was created to replace the Militias, the Ordenanças and the Guarda Real da Polícia (GRP) [Royal Police Guard]. The RGN’s main function was to maintain order throughout the various Provinces of the country including Overseas, thus being a type of Gendarmerie force and in case of war they could have its soldiers called for war. Unlike the regular Army, the RGN was considered more liberal and radical, especially in the urban areas and often rather than stopping the protests it joined them and when this happened the danger towards the regime increased.

While the Army, Navy and RGN worked mostly on a volunteer basis, at times, it was necessary to recruit people by “force” to fill the quotas but the recruitment method was changed. Previously recruitment was done at a Municipality level, in which certain Municipalities were forced to provide troops to the Army in an unequal way with Municipalities in Alentejo such as Olivença, Elvas, Portalegre and Mértola being especially overburdened with having to fill more than one Regiment. This meant that if a war broke out with this system, the already less populated Alentejo would provide almost a quarter if not more of the troops. Thus, a new Countrywide level recruitment was implemented in which every Municipality was forced to provide willing recruits to fill the local Regiments. This meant the burden in each Municipality was far lower and more equal with no Municipality being overburdened anymore which in turn helped the country’s demographics.

The 1830s were luckily peaceful for Portugal in terms of conflicts. Aside from the quick recovery of Olivença and the intervention in the Carlist War where the Portuguese soldiers helped pacify Galiza, Leão [León] and Astúrias, there was nothing else of note, at least in Europe. But rather than falling into stagnation or decline, the Armed Forces continued to improve their capabilities thanks to the actions of the two Marshal politicians Saldanha and Vila Flor. These two had an interest in not only having the Armed Forces’ loyalty but also keeping it modernized in case of war, both of them had seen the country be invaded and taken without any real opposition during the Napoleonic War and to them, as military men, it was a humiliation that they had no intention of seeing again.

Keeping the Armed Forces officers up to date was deeply necessary and the Real Escola do Ezército (REE) [Royal Army School] and the Real Escola da Marinha (REM) [Royal Navy School] played a crucial role in this endeavour and without it being the aim, of civil engineering as well. These officers were also present in the conflicts taking place around Europe namely in the Carlist War, the French Conquest of Argélia [Algeria], the Egyptian-Ottoman Wars and the Revolts in Bélgica and Polónia, taking notes of the war doctrines and innovations before immediately bringing them to be discussed and taught.

The biggest problem Portugal faced was its dependency on foreign weaponry as despite having an arms industry it seemed incapable of producing weapons. Thus the various Governments passed legislation to modernize the Lisboa Army Arsenal with industrial machinery powered by water and steam and the same happened in its branches in Porto, Estremoz and Goa which not only helped make the country self-sustained in terms of armament and reduce the costs but also employed the local populations. But the Marshals were not happy with having the country just keep up with the rest of Europe, they wanted it to outperform the others at least in weapon quality. The gunsmiths, who were increasing in numbers, began picking parts from different foreign weapons and making puzzles out of them as they created new models of weapons with what they thought to be the best part of each.

Gunsmith António Mendes Lobo for Lisboa created the Luza Modelo 1838 musket using components from the British Brown Bess, the Spanish M1752 and the French Modèle 1777 but with a percussion lock or cap lock mechanism. The Luza M1838 was the first native weapon produced in Portugal in many years despite being an amalgamation of foreign ones. Initially, it had several problems, the worst of which was that some of them temporarily blinded the soldier firing it but the gunsmiths quickly fixed the mistakes and it was produced on a large scale since the early 1840s making it a cheap modern musket for the Portuguese Armed Forces. The gunsmiths also developed the first Portuguese prototypes of percussion lock rifles but none were approved for use. Yet...

Regarding the Navy, the Governments did their best to have it recover the power it lost with the Independence of Brazil, which saw a large portion of the fleet declare for the new nation. Just like the Army Arsenal, the Navy Arsenal was modernized and so was the important Damão Naval Shipyard that produced ships for the Portuguese Indian Ocean Fleet. There were plans to make a new naval shipyard in Matozinhos/Leça do Bailio in Northern Portugal to increase the Navy’s capabilities but they did not go forward yet due to the lack of consensus from the politicians.

With the Age of Sail ending, the Portuguese Navy began lobbying the Governments to have the first war steamboats built to keep competing with other navies but the costs to build such ships were higher and the shipyards lacked the means to build them and thus the country did not invest in this new technology until the very last years of the 1830s when the Duque de Bragança and the Dona Maria II, the first two paddlewheel steam warships in the Navy, were built. These two made their maiden voyages in 1840 but private steamships were already conducting voyages, especially to Rio de Janeiro, Londres and Nova Iorque [New York].

Despite the relative lack of investment, the Portuguese Navy had in 1840, 10 Ships-of-the-Line, 12 Frigates, 8 Corvettes, 18 Brigs, 2 Steam Ships along with many more support and transport ships in the Mainland and 2 Ships-of-the-Line, 3 Frigates and 5 Corvettes in the Indian Ocean Fleet for a total of 80 ships, making it larger than the Spanish Navy, because it had been divided between the Liberals and Absolutists, and roughly the same size as the Brazilian Navy allowing the country to project its force worldwide despite not being in the same level as Reino Unido or França.

Concrete training of the Portuguese soldiers, if it could be called that, was done in the many Portuguese Overseas possessions which witnessed an increase in the number of troops thanks to the improvement of the living conditions, salaries and defences. But these improvements were not enough especially in Moçambique where the local opponents were particularly strong as stated before. Another problem of the Overseas fighting had to do with it being guerilla warfare and not conventional warfare. This and the often insufficient numbers made the Portuguese forces organize themselves into Companies or Battalions or not even be organized at all and often only the superior weaponry allowed them to win the battles. The training of the sailors was even more complicated because the only opponent they could face was pirates and slavers which obviously were no threat at all.

While the Army commanders, excluding Saldanha and Vila Flor, had been against intervening in Espanha outside of Olivença, by the end of the decade they, along with the Navy commanders, were debating a possible intervention against Marrocos in hopes of emulating França’s Conquest of Argélia and emulate their forefathers’ glory in a sort of Romanticism thought that was spreading in the country glorifying the “Golden Age of Portugal” which had to be revived. But the politicians outside of the military sphere were not so keen on an invasion of this calibre or upset Reino Unido and other European countries.

Diplomatic Policy:

In 1829, Áustria, Rúsia, Duas Sicílias [Two Sicilies] and Sardenha [Sardinia] ceased their diplomatic relations with Portugal following the failure of the Conspiração do Infante and the subsequent repression of the Absolutists in the country but in truth these countries had been searching for a pretext to do it even earlier because they considered the Portuguese Liberal regime a threat to their interests and wanted it contained.

Carlos X of França, another Absolutist Monarch also thought about stopping diplomatic relations with Portugal but his Ministers and Advisors urged him to not take that approach in hopes of preventing a revolution that grew in likelihood with the constant reactionary measures promoted by the French King, by keeping itself within a good relationship with a clearly Liberal country. But the revolution happened anyway in 1830 and Carlos X of França was dethroned and replaced by his Liberal cousin Luíz Filipe I de Orleães who also sustained his regime in some capacity in his good relations with Portugal especially when he too, because of his usurpation, needed diplomatic support that Portugal provided him with. But despite this early mutually beneficial partnership, Luíz Filipe felt betrayed when Augusto de Boarné was chosen over his many sons to be Maria II’s consort and thus he cut relations with Portugal in 1833.

He did, however, recognize that his decision had bad repercussions for França but mostly for his regime which lacked international support and only sent Portugal to Reino Unido’s orbit so he rescinded his order in early 1835. For the remaining half of the decade, Portuguese-French relations were at an all-time high despite the King’s anger with both becoming important commercial and diplomatic partners counterbalancing the Reino Unido’s power in some capacity.

Prúsia, the third member of the Santa Aliança [Holy Alliance] surprised the other two by not cutting diplomatic ties with Portugal. The Prussians considered that Portugal was too far away to be a threat to their country, at least in the short term, and that Portugal’s value as an economic partner outweighed the danger of their Liberal Regime. Just like Carlos X of França, Frederico Guilherme III [Frederick William III] and his Ministers tried to appeal to the liberals in their country by keeping good relations with a Liberal country but unlike the French, the Prussians managed to do just that without having to face revolts. Commercial ties between Prúsia and Portugal improved with the former finding cheap colonial products such as sugar, coffee, tobacco and spices as well as finding some uses for Portuguese marble and interest in Portuguese wines and the latter gaining another source of coal, iron and food products.

The Prussian position was very important in convincing the new King Fernando II das Duas Sicílias to reestablish relations with Portugal as soon as he got crowned in 1830. Fernando already having a good reputation in his country seemed to be considered a reformist and until 1837 many believed and hoped he would install a Liberal Regime but after violently suppressing liberal protesters in Sicília, such notion disappeared. Nevertheless, he continued to have good relations with Portugal.

Aside from trying to improve relations with the Santa Aliança in which the results depended on the country, Portuguese diplomats also improved relations with the Nordic countries. Despite the reactionary phase of his reign, Frederico VI da Dinamarca accepted Portuguese attempts at friendship quite willing and so did Carlos XIV da Suécia-Noruega whose son Óscar was married to one of Augusto I de Portugal’s sisters Jozefina de Loixetemberga [Josephine of Leuchtenberg]. Both countries became important markets for Portuguese colonial products but especially for Portuguese wine which gained traction against the competing wines.

Despite Portugal recognizing Bélgica’s independence and becoming a very important political, diplomatic and economic partner to the new country, relations between Portugal and Holanda [Netherlands] remained stable. Baviera was another country that benefitted a lot from having good relations with Portugal with Luíz I ripping as many benefits as he could from these relations. Aside from economic benefits, Munique [Munich] replaced Viena as Portugal’s main line of communication with the southern part of the Confedereção Germânica [German Confederation] and even with Viena itself, increasing its international position and prestige.

It was also Luíz I that brought about the biggest diplomatic victory that Portugal had in the 1830s thanks to the marriage of Maximiliano de Boarné with Maria Nicolaevena da Rúsia in 1839. As already stated, the marriage led to the restoration of Portuguese-Russian relations with the reopening of the legations in both capitals. This event was extremely important for the Portuguese regime because it guaranteed the continuation of Liberalism in the country as no invasion would occur. It also left Áustria under pressure to re-establish relations with Portugal.

With Reino Unido and Espanha, Portugal’s usual ally and usual threat respectively, the relationships remained stable. Both countries felt it increasingly harder to influence Portugal as the country had not recovered from the wars and economic crisis but seemed to have regained its capacity to project power and pursue an independent foreign policy and trade. This was hard to swallow for them.

Summing up, the Portuguese diplomatic strategy was as it always was, to promote peace and trade between nations but also increasingly more interested in finding markets for its products and not be dependent on just one ally. Despite the country being at a certain armed peace and a beacon of Liberalism, no one in the country or outside wanted a new war and Portuguese diplomats made their contribution to this goal whenever possible often forsaking expanding Liberalism in favour of keeping good relations with the world.

Portugal had the following legations in 1840 (In brackets are the year where they were first established):

In Europe;

This Update is slightly small but I think it convenes everything I wanted to address regarding the Armed Forces and Diplomacy. The next Updates will be a tour around Europe and Brazil. I have written about Spain but I will try to condense it further and I still have other countries to write about. I plan on not taking six chapters or so...

Thank you for sparing time reading and I hope everyone has a nice day and stays safe.

Portugal began the 19th Century with many military commitments due to the state of war that Europe endured at the time. Under these conditions, the size of the Portuguese Army swelled to levels never seen before: in 1807 there were 24 Infantry Regiments, 12 Cavalry Regiments, 4 Artillery Regiments, 48 Militia Regiments, 1 Legion of Light Troops and 24 Ordenança Brigades for a total of about 150 000 soldiers.

Even with so many soldiers, the army’s first engagements after Junô [Junot] was expelled did not achieve the expected results and the astronomical military expenditures were only harming the country’s finances. Things only changed when British Generals such as Artur Uéselei [Arthur Wellesley] and Guilherme Beresforde [William Beresford] began drilling the Portuguese troops in the joint Anglo-Portuguese Army turning subpar troops into one of Europe’s finest due to their capability to properly follow orders and adaptability. Uéselei [Wellesley] himself requested Portuguese troops to fight in the famous Battle of Uáterló [Waterloo] but time did not allow it.

When the European conflicts ceased and Liberalism was implemented in Portugal, the Portuguese Army had its size greatly reduced to keep the military expenditures low since they were the main reason for the country’s Public Debt being so high. This caused some resentment in the Armed Forces with many of its officials sympathizing with the Absolutist cause which they believed was more beneficial for them. Thus it was no surprise that Prince Miguel and later Queen Dowager Carlota Joaquina and the Duke of Cadaval could count with plenty of support in the Armed Forces.

Only when Cadaval’s insurrection was defeated did the situation start to change when many of the Absolutist officials fled abroad in fear of reprisals and officials sympathising with Liberalism became the norm. Despite this change, the Armed Forces were always considered more conservative. The Reforma dos Marechais [Marshals’ Reform] (1828-1832) was the Armed Forces’ first overhauled since 1806-1808. It set the size of the Army to 40 000 soldiers and fixed the Portuguese Regiment size to 2 000 men (1 000 in Cavalry Regiments). Thus the country had:

- 10 Infantry Regiments (20 000 soldiers)

- 3 Caçador Regiments (6 000 soldiers)

- 5 Cavalry Regiments (5 000 soldiers)

- 4 Artillery Regiments (8 000 soldiers)

- The Regiment of the Royal Guard of Halberdiers (1 000 soldiers)

1st Infantry Regiment [Nº1] Tomar (Estremadura)

2nd Infantry Regiment [Nº2] Loulé (Algarve)

3rd Infantry Regiment [Nº3] Elvas (Alto Alentejo)

4th Infantry Regiment [Nº4] Penamacor (Beira Interior)

5th Infantry Regiment [Nº5] Moncorvo (Tráz-os-Montes)

6th Infantry Regiment [Nº6] Porto (Douro Litoral)

7th Infantry Regiment [Nº7] Lisboa (Grande Lisboa)

8th Infantry Regiment [Nº8] Beja (Baixo Alentejo)

9th Infantry Regiment [Nº9] Viana (Minho)

10th Infantry Regiment [Nº10] Soure (Beira Litoral)

1st Caçador Regiment [Nº1] Portalegre (Alto Alentejo)

2nd Caçador Regiment [Nº2] Vila Real (Tráz-os-Montes)

3rd Caçador Regiment [Nº3] Lamego (Beira Central)

1st Cavalry Regiment [Nº1] Santarém (Estremadura)

2nd Cavalry Regiment [Nº2] Moura (Baixo Alentejo)

3rd Cavalry Regiment [Nº3] Valpaços (Tráz-os-Montes)

4th Cavalry Regiment [Nº4] Vizeu (Beira Central)

5th Cavalry Regiment [Nº5] Barbacena (Alto Alentejo)

1st Artillery Regiment [Nº1] Mafra (Grande Lisboa)

2nd Artillery Regiment [Nº2] Tavira (Algarve)

3rd Artillery Regiment [Nº3] Fronteira (Alto Alentejo)

4th Artillery Regiment [Nº4] Guimarães (Minho)

In addition to the regular Army, the Real Guard Nacional (RGN) [Royal National Guard] was created to replace the Militias, the Ordenanças and the Guarda Real da Polícia (GRP) [Royal Police Guard]. The RGN’s main function was to maintain order throughout the various Provinces of the country including Overseas, thus being a type of Gendarmerie force and in case of war they could have its soldiers called for war. Unlike the regular Army, the RGN was considered more liberal and radical, especially in the urban areas and often rather than stopping the protests it joined them and when this happened the danger towards the regime increased.

While the Army, Navy and RGN worked mostly on a volunteer basis, at times, it was necessary to recruit people by “force” to fill the quotas but the recruitment method was changed. Previously recruitment was done at a Municipality level, in which certain Municipalities were forced to provide troops to the Army in an unequal way with Municipalities in Alentejo such as Olivença, Elvas, Portalegre and Mértola being especially overburdened with having to fill more than one Regiment. This meant that if a war broke out with this system, the already less populated Alentejo would provide almost a quarter if not more of the troops. Thus, a new Countrywide level recruitment was implemented in which every Municipality was forced to provide willing recruits to fill the local Regiments. This meant the burden in each Municipality was far lower and more equal with no Municipality being overburdened anymore which in turn helped the country’s demographics.

The 1830s were luckily peaceful for Portugal in terms of conflicts. Aside from the quick recovery of Olivença and the intervention in the Carlist War where the Portuguese soldiers helped pacify Galiza, Leão [León] and Astúrias, there was nothing else of note, at least in Europe. But rather than falling into stagnation or decline, the Armed Forces continued to improve their capabilities thanks to the actions of the two Marshal politicians Saldanha and Vila Flor. These two had an interest in not only having the Armed Forces’ loyalty but also keeping it modernized in case of war, both of them had seen the country be invaded and taken without any real opposition during the Napoleonic War and to them, as military men, it was a humiliation that they had no intention of seeing again.

Keeping the Armed Forces officers up to date was deeply necessary and the Real Escola do Ezército (REE) [Royal Army School] and the Real Escola da Marinha (REM) [Royal Navy School] played a crucial role in this endeavour and without it being the aim, of civil engineering as well. These officers were also present in the conflicts taking place around Europe namely in the Carlist War, the French Conquest of Argélia [Algeria], the Egyptian-Ottoman Wars and the Revolts in Bélgica and Polónia, taking notes of the war doctrines and innovations before immediately bringing them to be discussed and taught.

The biggest problem Portugal faced was its dependency on foreign weaponry as despite having an arms industry it seemed incapable of producing weapons. Thus the various Governments passed legislation to modernize the Lisboa Army Arsenal with industrial machinery powered by water and steam and the same happened in its branches in Porto, Estremoz and Goa which not only helped make the country self-sustained in terms of armament and reduce the costs but also employed the local populations. But the Marshals were not happy with having the country just keep up with the rest of Europe, they wanted it to outperform the others at least in weapon quality. The gunsmiths, who were increasing in numbers, began picking parts from different foreign weapons and making puzzles out of them as they created new models of weapons with what they thought to be the best part of each.

Lisboa's Army Arsenal

Gunsmith António Mendes Lobo for Lisboa created the Luza Modelo 1838 musket using components from the British Brown Bess, the Spanish M1752 and the French Modèle 1777 but with a percussion lock or cap lock mechanism. The Luza M1838 was the first native weapon produced in Portugal in many years despite being an amalgamation of foreign ones. Initially, it had several problems, the worst of which was that some of them temporarily blinded the soldier firing it but the gunsmiths quickly fixed the mistakes and it was produced on a large scale since the early 1840s making it a cheap modern musket for the Portuguese Armed Forces. The gunsmiths also developed the first Portuguese prototypes of percussion lock rifles but none were approved for use. Yet...

Regarding the Navy, the Governments did their best to have it recover the power it lost with the Independence of Brazil, which saw a large portion of the fleet declare for the new nation. Just like the Army Arsenal, the Navy Arsenal was modernized and so was the important Damão Naval Shipyard that produced ships for the Portuguese Indian Ocean Fleet. There were plans to make a new naval shipyard in Matozinhos/Leça do Bailio in Northern Portugal to increase the Navy’s capabilities but they did not go forward yet due to the lack of consensus from the politicians.

With the Age of Sail ending, the Portuguese Navy began lobbying the Governments to have the first war steamboats built to keep competing with other navies but the costs to build such ships were higher and the shipyards lacked the means to build them and thus the country did not invest in this new technology until the very last years of the 1830s when the Duque de Bragança and the Dona Maria II, the first two paddlewheel steam warships in the Navy, were built. These two made their maiden voyages in 1840 but private steamships were already conducting voyages, especially to Rio de Janeiro, Londres and Nova Iorque [New York].

Despite the relative lack of investment, the Portuguese Navy had in 1840, 10 Ships-of-the-Line, 12 Frigates, 8 Corvettes, 18 Brigs, 2 Steam Ships along with many more support and transport ships in the Mainland and 2 Ships-of-the-Line, 3 Frigates and 5 Corvettes in the Indian Ocean Fleet for a total of 80 ships, making it larger than the Spanish Navy, because it had been divided between the Liberals and Absolutists, and roughly the same size as the Brazilian Navy allowing the country to project its force worldwide despite not being in the same level as Reino Unido or França.

Concrete training of the Portuguese soldiers, if it could be called that, was done in the many Portuguese Overseas possessions which witnessed an increase in the number of troops thanks to the improvement of the living conditions, salaries and defences. But these improvements were not enough especially in Moçambique where the local opponents were particularly strong as stated before. Another problem of the Overseas fighting had to do with it being guerilla warfare and not conventional warfare. This and the often insufficient numbers made the Portuguese forces organize themselves into Companies or Battalions or not even be organized at all and often only the superior weaponry allowed them to win the battles. The training of the sailors was even more complicated because the only opponent they could face was pirates and slavers which obviously were no threat at all.

While the Army commanders, excluding Saldanha and Vila Flor, had been against intervening in Espanha outside of Olivença, by the end of the decade they, along with the Navy commanders, were debating a possible intervention against Marrocos in hopes of emulating França’s Conquest of Argélia and emulate their forefathers’ glory in a sort of Romanticism thought that was spreading in the country glorifying the “Golden Age of Portugal” which had to be revived. But the politicians outside of the military sphere were not so keen on an invasion of this calibre or upset Reino Unido and other European countries.

Diplomatic Policy:

In 1829, Áustria, Rúsia, Duas Sicílias [Two Sicilies] and Sardenha [Sardinia] ceased their diplomatic relations with Portugal following the failure of the Conspiração do Infante and the subsequent repression of the Absolutists in the country but in truth these countries had been searching for a pretext to do it even earlier because they considered the Portuguese Liberal regime a threat to their interests and wanted it contained.

Carlos X of França, another Absolutist Monarch also thought about stopping diplomatic relations with Portugal but his Ministers and Advisors urged him to not take that approach in hopes of preventing a revolution that grew in likelihood with the constant reactionary measures promoted by the French King, by keeping itself within a good relationship with a clearly Liberal country. But the revolution happened anyway in 1830 and Carlos X of França was dethroned and replaced by his Liberal cousin Luíz Filipe I de Orleães who also sustained his regime in some capacity in his good relations with Portugal especially when he too, because of his usurpation, needed diplomatic support that Portugal provided him with. But despite this early mutually beneficial partnership, Luíz Filipe felt betrayed when Augusto de Boarné was chosen over his many sons to be Maria II’s consort and thus he cut relations with Portugal in 1833.

He did, however, recognize that his decision had bad repercussions for França but mostly for his regime which lacked international support and only sent Portugal to Reino Unido’s orbit so he rescinded his order in early 1835. For the remaining half of the decade, Portuguese-French relations were at an all-time high despite the King’s anger with both becoming important commercial and diplomatic partners counterbalancing the Reino Unido’s power in some capacity.

Prúsia, the third member of the Santa Aliança [Holy Alliance] surprised the other two by not cutting diplomatic ties with Portugal. The Prussians considered that Portugal was too far away to be a threat to their country, at least in the short term, and that Portugal’s value as an economic partner outweighed the danger of their Liberal Regime. Just like Carlos X of França, Frederico Guilherme III [Frederick William III] and his Ministers tried to appeal to the liberals in their country by keeping good relations with a Liberal country but unlike the French, the Prussians managed to do just that without having to face revolts. Commercial ties between Prúsia and Portugal improved with the former finding cheap colonial products such as sugar, coffee, tobacco and spices as well as finding some uses for Portuguese marble and interest in Portuguese wines and the latter gaining another source of coal, iron and food products.

The Prussian position was very important in convincing the new King Fernando II das Duas Sicílias to reestablish relations with Portugal as soon as he got crowned in 1830. Fernando already having a good reputation in his country seemed to be considered a reformist and until 1837 many believed and hoped he would install a Liberal Regime but after violently suppressing liberal protesters in Sicília, such notion disappeared. Nevertheless, he continued to have good relations with Portugal.

Aside from trying to improve relations with the Santa Aliança in which the results depended on the country, Portuguese diplomats also improved relations with the Nordic countries. Despite the reactionary phase of his reign, Frederico VI da Dinamarca accepted Portuguese attempts at friendship quite willing and so did Carlos XIV da Suécia-Noruega whose son Óscar was married to one of Augusto I de Portugal’s sisters Jozefina de Loixetemberga [Josephine of Leuchtenberg]. Both countries became important markets for Portuguese colonial products but especially for Portuguese wine which gained traction against the competing wines.

Despite Portugal recognizing Bélgica’s independence and becoming a very important political, diplomatic and economic partner to the new country, relations between Portugal and Holanda [Netherlands] remained stable. Baviera was another country that benefitted a lot from having good relations with Portugal with Luíz I ripping as many benefits as he could from these relations. Aside from economic benefits, Munique [Munich] replaced Viena as Portugal’s main line of communication with the southern part of the Confedereção Germânica [German Confederation] and even with Viena itself, increasing its international position and prestige.

It was also Luíz I that brought about the biggest diplomatic victory that Portugal had in the 1830s thanks to the marriage of Maximiliano de Boarné with Maria Nicolaevena da Rúsia in 1839. As already stated, the marriage led to the restoration of Portuguese-Russian relations with the reopening of the legations in both capitals. This event was extremely important for the Portuguese regime because it guaranteed the continuation of Liberalism in the country as no invasion would occur. It also left Áustria under pressure to re-establish relations with Portugal.

With Reino Unido and Espanha, Portugal’s usual ally and usual threat respectively, the relationships remained stable. Both countries felt it increasingly harder to influence Portugal as the country had not recovered from the wars and economic crisis but seemed to have regained its capacity to project power and pursue an independent foreign policy and trade. This was hard to swallow for them.

Summing up, the Portuguese diplomatic strategy was as it always was, to promote peace and trade between nations but also increasingly more interested in finding markets for its products and not be dependent on just one ally. Despite the country being at a certain armed peace and a beacon of Liberalism, no one in the country or outside wanted a new war and Portuguese diplomats made their contribution to this goal whenever possible often forsaking expanding Liberalism in favour of keeping good relations with the world.

Portugal had the following legations in 1840 (In brackets are the year where they were first established):

In Europe;

- Legation in Roma (1641) Estados Papais [Papal States] and Northern Italian Peninsula

- Legation in Londres (1641) Reino Unido and Hanover (the latter until 1837)

- Legation in Haia [The Hague] (1641) Holanda

- Legation in Paris (1641) França and Império Otomano [Interrupted between 1833 and 1835]

- Legation in Estocolmo (1641) Suécia-Noruega

- Legation in Madrid (1669) Espanha

- Legation in Berlim (1708) Prúsia and Northern Confederação Germânica

- Legation in Nápoles (1753) Duas Sicílias [Interrupted between 1829 and 1830]

- Legation in São Petersburgo (1779) Rúsia [Interrupted between 1829 and 1839]

- Legation in Copenhaga (1786) Dinamarca

- Legation in Bruxelas (1834) Bélgica

- Legation in Munique (1834) Baviera, Grécia and Southern Confederação Germânica

- Legation in Viena (1696) [Interrupted in 1829]

- Legation in Turim (1760) [Interrupted in 1829]

- Legation in Uáxinguetone [Washington] (1794) Estados Unidos and Central America

- Legation in Rio de Janeiro (1826) Brazil and South America

This Update is slightly small but I think it convenes everything I wanted to address regarding the Armed Forces and Diplomacy. The next Updates will be a tour around Europe and Brazil. I have written about Spain but I will try to condense it further and I still have other countries to write about. I plan on not taking six chapters or so...

Thank you for sparing time reading and I hope everyone has a nice day and stays safe.

Last edited:

Great chapter, can’t wait for more. Question though, will Portugal make use of a “foreign legion” like France did? I see the Boers could be used, given they get a home in Lourenço Marques, where some Boers are staying.Military Policy:

Portugal began the 19th Century with many military commitments due to the state of war that Europe endured at the time. Under these conditions, the size of the Portuguese Army swelled to levels never seen before: in 1807 there were 24 Infantry Regiments, 12 Cavalry Regiments, 4 Artillery Regiments, 48 Militia Regiments, 1 Legion of Light Troops and 24 Ordenança Brigades for a total of about 150 000 soldiers.

Even with so many soldiers, the army’s first engagements after Junô [Junot] was expelled did not achieve the expected results and the astronomical military expenditures were only harming the country’s finances. Things only changed when British Generals such as Artur Uéselei [Arthur Wellesley] and Guilherme Beresforde [William Beresford] began drilling the Portuguese troops in the joint Anglo-Portuguese Army turning subpar troops into one of Europe’s finest due to their capability to properly follow orders and adaptability. Uéselei [Wellesley] himself requested Portuguese troops to fight in the famous Battle of Uáterló [Waterloo] but time did not allow it.

When the European conflicts ceased and Liberalism was implemented in Portugal, the Portuguese Army had its size greatly reduced to keep the military expenditures low since they were the main reason for the country’s Public Debt being so high. This caused some resentment in the Armed Forces with many of its officials sympathizing with the Absolutist cause which they believed was more beneficial for them. Thus it was no surprise that Prince Miguel and later Queen Dowager Carlota Joaquina and the Duke of Cadaval could count with plenty of support in the Armed Forces.

Only when Cadaval’s insurrection was defeated did the situation start to change when many of the Absolutist officials fled abroad in fear of reprisals and officials sympathising with Liberalism became the norm. Despite this change, the Armed Forces were always considered more conservative. The Reforma dos Marechais [Marshals’ Reform] (1828-1832) was the Armed Forces’ first overhauled since 1806-1808. It set the size of the Army to 40 000 soldiers and fixed the Portuguese Regiment size to 2 000 men (1 000 in Cavalry Regiments). Thus the country had:

- 10 Infantry Regiments (20 000 soldiers)

- 3 Caçador Regiments (6 000 soldiers)

- 5 Cavalry Regiments (5 000 soldiers)

- 4 Artillery Regiments (8 000 soldiers)

- The Regiment of the Royal Guard of Halberdiers (1 000 soldiers)

View attachment 875593

1st Infantry Regiment [Nº1] Tomar (Estremadura)

2nd Infantry Regiment [Nº2] Loulé (Algarve)

3rd Infantry Regiment [Nº3] Elvas (Alto Alentejo)

4th Infantry Regiment [Nº4] Penamacor (Beira Interior)

5th Infantry Regiment [Nº5] Moncorvo (Tráz-os-Montes)

6th Infantry Regiment [Nº6] Porto (Douro Litoral)

7th Infantry Regiment [Nº7] Lisboa (Grande Lisboa)

8th Infantry Regiment [Nº8] Beja (Baixo Alentejo)

9th Infantry Regiment [Nº9] Viana (Minho)

10th Infantry Regiment [Nº10] Soure (Beira Litoral)

1st Caçador Regiment [Nº1] Portalegre (Alto Alentejo)

2nd Caçador Regiment [Nº2] Vila Real (Tráz-os-Montes)

3rd Caçador Regiment [Nº3] Lamego (Beira Central)

1st Cavalry Regiment [Nº1] Santarém (Estremadura)

2nd Cavalry Regiment [Nº2] Moura (Baixo Alentejo)

3rd Cavalry Regiment [Nº3] Valpaços (Tráz-os-Montes)

4th Cavalry Regiment [Nº4] Vizeu (Beira Central)

5th Cavalry Regiment [Nº5] Barbacena (Alto Alentejo)

1st Artillery Regiment [Nº1] Mafra (Grande Lisboa)

2nd Artillery Regiment [Nº2] Tavira (Algarve)

3rd Artillery Regiment [Nº3] Fronteira (Alto Alentejo)

4th Artillery Regiment [Nº4] Guimarães (Minho)

In addition to the regular Army, the Real Guard Nacional (RGN) [Royal National Guard] was created to replace the Militias, the Ordenanças and the Guarda Real da Polícia (GRP) [Royal Police Guard]. The RGN’s main function was to maintain order throughout the various Provinces of the country including Overseas, thus being a type of Gendarmerie force and in case of war they could have its soldiers called for war. Unlike the regular Army, the RGN was considered more liberal and radical, especially in the urban areas and often rather than stopping the protests it joined them and when this happened the danger towards the regime increased.

While the Army, Navy and RGN worked mostly on a volunteer basis, at times, it was necessary to recruit people by “force” to fill the quotas but the recruitment method was changed. Previously recruitment was done at a Municipality level, in which certain Municipalities were forced to provide troops to the Army in an unequal way with Municipalities in Alentejo such as Olivença, Elvas, Portalegre and Mértola being especially overburdened with having to fill more than one Regiment. This meant that if a war broke out with this system, the already less populated Alentejo would provide almost a quarter if not more of the troops. Thus, a new Countrywide level recruitment was implemented in which every Municipality was forced to provide willing recruits to fill the local Regiments. This meant the burden in each Municipality was far lower and more equal with no Municipality being overburdened anymore which in turn helped the country’s demographics.

The 1830s were luckily peaceful for Portugal in terms of conflicts. Aside from the quick recovery of Olivença and the intervention in the Carlist War where the Portuguese soldiers helped pacify Galiza, Leão [León] and Astúrias, there was nothing else of note, at least in Europe. But rather than falling into stagnation or decline, the Armed Forces continued to improve their capabilities thanks to the actions of the two Marshal politicians Saldanha and Vila Flor. These two had an interest in not only having the Armed Forces’ loyalty but also keeping it modernized in case of war, both of them had seen the country be invaded and taken without any real opposition during the Napoleonic War and to them, as military men, it was a humiliation that they had no intention of seeing again.

Keeping the Armed Forces officers up to date was deeply necessary and the Real Escola do Ezército (REE) [Royal Army School] and the Real Escola da Marinha (REM) [Royal Navy School] played a crucial role in this endeavour and without it being the aim, of civil engineering as well. These officers were also present in the conflicts taking place around Europe namely in the Carlist War, the French Conquest of Argélia [Algeria], the Egyptian-Ottoman Wars and the Revolts in Bélgica and Polónia, taking notes of the war doctrines and innovations before immediately bringing them to be discussed and taught.

The biggest problem Portugal faced was its dependency on foreign weaponry as despite having an arms industry it seemed incapable of producing weapons. Thus the various Governments passed legislation to modernize the Lisboa Army Arsenal with industrial machinery powered by water and steam and the same happened in its branches in Porto, Estremoz and Goa which not only helped make the country self-sustained in terms of armament and reduce the costs but also employed the local populations. But the Marshals were not happy with having the country just keep up with the rest of Europe, they wanted it to outperform the others at least in weapon quality. The gunsmiths, who were increasing in numbers, began picking parts from different foreign weapons and making puzzles out of them as they created new models of weapons with what they thought to be the best part of each.

Gunsmith António Mendes Lobo for Lisboa created the Luza Modelo 1838 musket using components from the British Brown Bess, the Spanish M1752 and the French Modèle 1777 but with a percussion lock or cap lock mechanism. The Luza M1838 was the first native weapon produced in Portugal in many years despite being an amalgamation of foreign ones. Initially, it had several problems, the worst of which was that some of them temporarily blinded the soldier firing it but the gunsmiths quickly fixed the mistakes and it was produced on a large scale since the early 1840s making it a cheap modern musket for the Portuguese Armed Forces. The gunsmiths also developed the first Portuguese prototypes of percussion lock rifles but none were approved for use. Yet...

Regarding the Navy, the Governments did their best to have it recover the power it lost with the Independence of Brazil, which saw a large portion of the fleet declare for the new nation. Just like the Army Arsenal, the Navy Arsenal was modernized and so was the important Damão Naval Shipyard that produced ships for the Portuguese Indian Ocean Fleet. There were plans to make a new naval shipyard in Matozinhos/Leça do Bailio in Northern Portugal to increase the Navy’s capabilities but they did not go forward yet due to the lack of consensus from the politicians.

With the Age of Sail ending, the Portuguese Navy began lobbying the Governments to have the first war steamboats built to keep competing with other navies but the costs to build such ships were higher and the shipyards lacked the means to build them and thus the country did not invest in this new technology until the very last years of the 1830s when the Duque de Bragança and the Dona Maria II, the first two paddlewheel steam warships in the Navy, were built. These two made their maiden voyages in 1840 but private steamships were already conducting voyages, especially to Rio de Janeiro, Londres and Nova Iorque [New York].

Despite the relative lack of investment, the Portuguese Navy had in 1840, 10 Ships-of-the-Line, 12 Frigates, 8 Corvettes, 18 Brigs, 2 Steam Ships along with many more support and transport ships in the Mainland and 2 Ships-of-the-Line, 3 Frigates and 5 Corvettes in the Indian Ocean Fleet for a total of 80 ships, making it larger than the Spanish Navy, because it had been divided between the Liberals and Absolutists, and roughly the same size as the Brazilian Navy allowing the country to project its force worldwide despite not being in the same level as Reino Unido or França.

Concrete training of the Portuguese soldiers, if it could be called that, was done in the many Portuguese Overseas possessions which witnessed an increase in the number of troops thanks to the improvement of the living conditions, salaries and defences. But these improvements were not enough especially in Moçambique where the local opponents were particularly strong as stated before. Another problem of the Overseas fighting had to do with it being guerilla warfare and not conventional warfare. This and the often insufficient numbers made the Portuguese forces organize themselves into Companies or Battalions or not even be organized at all and often only the superior weaponry allowed them to win the battles. The training of the sailors was even more complicated because the only opponent they could face was pirates and slavers which obviously were no threat at all.

While the Army commanders, excluding Saldanha and Vila Flor, had been against intervening in Espanha outside of Olivença, by the end of the decade they, along with the Navy commanders, were debating a possible intervention against Marrocos in hopes of emulating França’s Conquest of Argélia and emulate their forefathers’ glory in a sort of Romanticism thought that was spreading in the country glorifying the “Golden Age of Portugal” which had to be revived. But the politicians outside of the military sphere were not so keen on an invasion of this calibre or upset Reino Unido and other European countries.

Diplomatic Policy:

In 1829, Áustria, Rúsia, Duas Sicílias [Two Sicilies] and Sardenha [Sardinia] ceased their diplomatic relations with Portugal following the failure of the Conspiração do Infante and the subsequent repression of the Absolutists in the country but in truth these countries had been searching for a pretext to do it even earlier because they considered the Portuguese Liberal regime a threat to their interests and wanted it contained.

Carlos X of França, another Absolutist Monarch also thought about stopping diplomatic relations with Portugal but his Ministers and Advisors urged him to not take that approach in hopes of preventing a revolution that grew in likelihood with the constant reactionary measures promoted by the French King, by keeping itself within a good relationship with a clearly Liberal country. But the revolution happened anyway in 1830 and Carlos X of França was dethroned and replaced by his Liberal cousin Luíz Filipe I de Orleães who also sustained his regime in some capacity in his good relations with Portugal especially when he too, because of his usurpation, needed diplomatic support that Portugal provided him with. But despite this early mutually beneficial partnership, Luíz Filipe felt betrayed when Augusto de Boarné was chosen over his many sons to be Maria II’s consort and thus he cut relations with Portugal in 1833.

He did, however, recognize that his decision had bad repercussions for França but mostly for his regime which lacked international support and only sent Portugal to Reino Unido’s orbit so he rescinded his order in early 1835. For the remaining half of the decade, Portuguese-French relations were at an all-time high despite the King’s anger with both becoming important commercial and diplomatic partners counterbalancing the Reino Unido’s power in some capacity.

Prúsia, the third member of the Santa Aliança [Holy Alliance] surprised the other two by not cutting diplomatic ties with Portugal. The Prussians considered that Portugal was too far away to be a threat to their country, at least in the short term, and that Portugal’s value as an economic partner outweighed the danger of their Liberal Regime. Just like Carlos X of França, Frederico Guilherme III [Frederick William III] and his Ministers tried to appeal to the liberals in their country by keeping good relations with a Liberal country but unlike the French, the Prussians managed to do just that without having to face revolts. Commercial ties between Prúsia and Portugal improved with the former finding cheap colonial products such as sugar, coffee, tobacco and spices as well as finding some uses for Portuguese marble and interest in Portuguese wines and the latter gaining another source of coal, iron and food products.

The Prussian position was very important in convincing the new King Fernando II das Duas Sicílias to reestablish relations with Portugal as soon as he got crowned in 1830. Fernando already having a good reputation in his country seemed to be considered a reformist and until 1837 many believed and hoped he would install a Liberal Regime but after violently suppressing liberal protesters in Sicília, such notion disappeared. Nevertheless, he continued to have good relations with Portugal.

Aside from trying to improve relations with the Santa Aliança in which the results depended on the country, Portuguese diplomats also improved relations with the Nordic countries. Despite the reactionary phase of his reign, Frederico VI da Dinamarca accepted Portuguese attempts at friendship quite willing and so did Carlos XIV da Suécia-Noruega whose son Óscar was married to one of Augusto I de Portugal’s sisters Jozefina de Loixetemberga [Josephine of Leuchtenberg]. Both countries became important markets for Portuguese colonial products but especially for Portuguese wine which gained traction against the competing wines.

Despite Portugal recognizing Bélgica’s independence and becoming a very important political, diplomatic and economic partner to the new country, relations between Portugal and Holanda [Netherlands] remained stable. Baviera was another country that benefitted a lot from having good relations with Portugal with Luíz I ripping as many benefits as he could from these relations. Aside from economic benefits, Munique [Munich] replaced Viena as Portugal’s main line of communication with the southern part of the Confedereção Germânica [German Confederation] and even with Viena itself, increasing its international position and prestige.