You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

To be a Fox and a Lion - A Different Nordic Renaissance

- Thread starter Milites

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 37 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 26: White Rose Victorious Chapter 27: The One Good Harvest Map of Denmark and Schleswig at the End of the Late Medieval Period (ca. 1490-1513) Chapter 28: On the Shores of a Restless Sea Chapter 29: A Thorny Olive Branch Chapter 30: Via Media Chapter 31: The Garefowl Feud Chapter 32: The Queen of the Eastern SeaTake your time! We'll always be ready for the next update, no matter how long it takes!Work is still being done on the next update, but real life did a number on me this past month. I hope to make up for it with a retroactively relevant minor intermission (as in - a standalone map) besides the upcoming Chapter 28.

Also, I've updated the map in the previous chapter after some very kind pointers from @Shnurre in regards to borders in Eastern Europe. Have a gander if you like

I wasn't aware of a stillbirth in 1523

Lars Bisgaard's most recent biography of Christian II. doesn't seem to mention it. Regardless, Elisabeth hasn't borne any more children since the birth of Christina in 1521. The couple was deeply enamoured though, so a few more pregnancies might be expected. This five year break in child bearing also has the added benefit of drastically improving the queen's otherwise rather shaky health, which means Christian might keep his wife for a good while longer than in OTL.

As for the stillbirth, it's mentioned on wikipedia, so it could be incorrect. It could also easily be butterflied away TTL, so it's not important or anything!

Map of Denmark and Schleswig at the End of the Late Medieval Period (ca. 1490-1513)

Author’s Note: A map originally made for another project which I've adapted to fit this timeline. Chronologically, it shows the administrative, ecclesiastical and urban division of the Danish realm and the Duchy of Schleswig in the period from 1490 (Schleswig) to the death of King Hans (Denmark) in 1513. While there might be some mistakes here and there, I can confidently say that this is probably the most accurate map available in English of the situation in Denmark just prior to the coronation of Christian II. Although the map does not advance the story as it stands at its current juncture, I thought it might be a nice reference point for new readers when the timeline returns to Scandinavian matters in a few updates' time. As such I've inserted it in the threadmarks immediately following the introduction. I hope you'll enjoy it as I work on Chapter 28 and the Hungarian situation

Sources:

Appel, Hans Henrik: At være almuen mægtig - de jyske bønder og øvrigheden på reformationstiden (Odense: Landbohistorisk Selskab, 1991)

Arup, Erik: Danmarks historie, Bind 2 - Stænderne i herrevælde (København, 1932)

Christensen, Harry: Len og Magt i Danmark 1439-1481 (Viborg: Universitetsforlaget i Aarhus, 1983)

Erslev, Kristian: Danmarks Len og Lensmænd i det sextende aarhundrede 1513-1596 (København, 1879)

Hørby, Kai & Venge, Mikael: Danmarks historie, Bind 2 - Tiden 1340-1648, første halvbind (København: Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag A.S., 1980)

Jespersen, Mikkel Leth: "Dronning Christines politiske rolle" in Dronningemagt i middelalderen edited by Jeppe Büchert Netterstrøm & Kasper H. Andersen (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2018)

Poulsen, Bjørn: "Slesvig før delingen i 1490: Et bidrag til senmiddelalderens finansforvaltning" in Historisk Tidsskrift 90 (1990): pp. 38-63

Last edited:

I gotta say, your maps are among the best I have ever seen! They could (and should!) be published

I gotta say, your maps are among the best I have ever seen! They could (and should!) be published

Thanks for the kind words! I do hope that they might one day be published in one form or another.

Excellent job!!

Thank you

What is a hundred in this context?

The hundreds (herreder in Danish and Norwegian, härader in Swedish) were the administrative/judicial subdivisions immediately below the fiefs. These were in turn made up of a number of parishes. The fiefs and hundreds of Scandinavia are, to a certain extent, comparable to how the shires of England were also divided into hundreds.

Last edited:

Chapter 28: On the Shores of a Restless Sea

Chapter 28

On the Shores of a Restless Sea

“The Turk is the rod of the Lord, Our God.”

- Martin Luther, 1528

“The trees of happiness with the roots of the poor Hungarians were pulled out by the powerful hand of the famous pasha, which was the unbreakable tower of the power of a happy and famous Sultan.”

- Kemalpaşazâde "Histories of the House of Osman", 1526

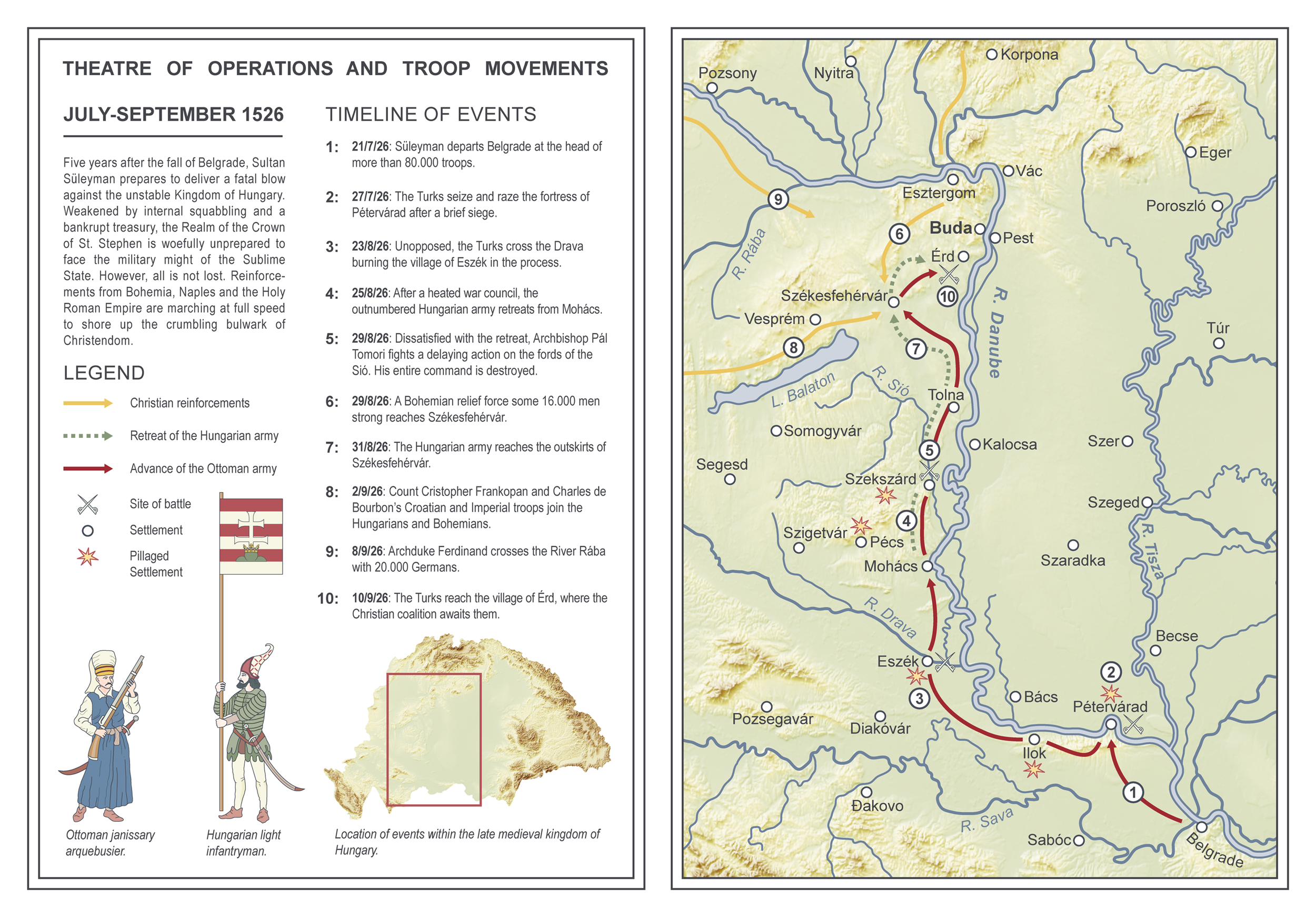

Thanks to Bishop Pál Tomori’s excellent spy network of[1], news of the Ottoman invasion quickly reached the court of King Louis II at Buda in early 1526. Although his wife’s political acumen had resolved much of the strife and division plaguing the Hungarian government, Louis II and his nobles continued to bicker. By March 1526, the order of mobilisation had still not been dispatched, prompting the magnates to formally protest that if the realm were lost it would be no fault of theirs as they “... had given good counsel to His Majesty.”[2]On the Shores of a Restless Sea

“The Turk is the rod of the Lord, Our God.”

- Martin Luther, 1528

“The trees of happiness with the roots of the poor Hungarians were pulled out by the powerful hand of the famous pasha, which was the unbreakable tower of the power of a happy and famous Sultan.”

- Kemalpaşazâde "Histories of the House of Osman", 1526

Matters were not helped by the steady flow of contradicting missives detailing the purported Turkish invasion route. Some reports suggested Transylvania as the entry point while others claimed that the main thrust would come at Belgrade or in Slavonia. In January 1526, the last titular despot of Serbia, Pavle Bakić, fled Ottoman territory with a small army, bringing with him the news that Süleyman aimed to strike directly at Buda: “... for once this chief city of the realm is taken, not a single castle will remain in Hungary that would not be his.”[3]

By April, king and court finally agreed to mobilise the detachments from the border regions. Summons were sent to Croatia-Slavonia and Transylvania where Count Cristopher Frankopan, Ban Francis Batthyány and Voivode John Zápolya began gathering troops for the coming campaign. However, while the king considered Batthyány to be one of his most loyal men, Frankopan and Zápolya were committed partisans of the anti-Habsburg magnate faction. By July 1526, the voivode had not yet left Transylvania, despite receiving a royal command that he was to “... set aside all other designs, as the approach of the enemy warrants that he hasten to the king with all Transylvanian forces."[4] While the Hungarian aristocracy from the core counties was marshalled at Buda, Louis also sent pleas for help to his brother-in-law Ferdinand and to his Bohemian subjects. Ferdinand’s hands were at the moment tied up in calming the unruly confessional waters at Speyer, but the Estates of Bohemia immediately granted the funds to assemble a force some 16.000 strong.[5]

Against this slowly assembling and ill-organised coalition stood the well-oiled military machine of the Sublime Porte. Süleyman commanded an impressive host close to 80.000 troops, ranging in quality from the professional, kapukulu Janissaries and the heavy provincial timariot cavalry to akinji light horse as well as Bosnian and Tatar auxiliaries.[6] Yet many within the upper echelons of the Jagiellonian army dismissed the prowess of the Turks, with Archbishop Pál Tomori even arguing that “... the Turkish army is large in numbers only, but is not well trained, the troops being too young and inexperienced in war because the Turks lost the flower of their soldiery on the island of Rhodes and elsewhere.”[7]

However, King Louis was not entirely convinced that his outnumbered force could defeat the enemy in the field, no matter what casualties he had sustained at Rhodes. Indeed, the rank and file soldiery was prone to poor discipline - to the point where common men-at-arms barefacedly muscled their way into the king’s war council to present their own ideas.[8] In late July 1526, word came that the Bohemian contingent had finished assembling near Prague and was on the march. The troops of Frankopan and Zápoly, however, remained at their mustering fields in Croatia and Transylvania, ostensibly out of fear that the Turks would come their way.

The Resurrection of Christ. Detail of the main altar at the Church of Liptószentandrás by an unknown artist, 1512. The resurrected Christ stands victoriously on top of his tomb surrounded by soldiers dressed respectively in Ottoman, Hungarian, Czech and German garbs. Note that of the four men, only the Turk remains asleep while the others are in various states of surprise and admiration.

From his seat at Speyer, Archduke Ferdinand was desperately trying to organise an imperial relief army. He had attempted to do so twice before in 1522 and 1524 (with little success), and when news reached the Diet of Suleyman’s imminent invasion, Ferdinand wasted little time in appealing to the German princes.[9] Mellowed by the concessions afforded them and with the prospect of a church council on the horizon, the imperial Estates voted en masse to provide the Archduke with a considerable grant in late July 1526. By then, Ferdinand had already dispatched an army some 4000 strong under Count Nicholas von Salm, one of his most able commanders, paid out of his own threadbare pocket.[10] Moreover, the Archduke scored an immense diplomatic victory when he cajoled the war-weary (and thoroughly disillusioned Venetians) to allow for and support the transfer of a part of Charles de Lannoy’s Neapolitan army to Dalmatia. As August began, Louis II was thus pleasantly surprised to hear that some 8000 Spanish, Italian and Albanian mercenaries under Charles de Bourbon were advancing up the road from Senj to Zagreb.[11]

By all accounts it would thus not be amiss to describe Louis II’s position as growing stronger by the day. Allied hosts were rushing to Buda from every compass point: Ferdinand with almost 20.000 Germans, Bourbon with his 8000 Neapolitans, the 16.000 Bohemians, 7000 Croats under Frankopan, 4000 Slavonians under Batthyány and Zápolya’s 15.000 Transylvanians. When united with the Hungarian army, the size of the Christian coalition would thus have dwarfed the combined strength of the crusader forces at Nicopolis and Varna.

Yet a belligerent mood had gripped the Hungarian nobility. The fall of Belgrade had put much of the realm’s southern reaches within Turkish striking distance, leaving whole counties scorched and depopulated. As such, the martial lords of Hungary were determined to meet the foe in the field sooner rather than later, certain that their own valour would make up for the Ottoman numerical superiority. Indeed, Archbishop Tomori had bitterly lamented the slowness of the Hungarian response, writing the king that “... I have written letters to Your Majesty week after week, but Your Majesty and the lords have failed even to shoe the horses!”[12] However, one should not judge King Louis too harshly. Mobilisation was delayed on account of the very real necessity of collecting the harvest needed to feed the troops and gathering the taxes granted in the Spring needed to pay them.

For his part, Sultan Süleyman was eager to accommodate the nobility. His plan was to advance along the right bank of the Danube, seek out the Hungarian army, defeat it in a decisive battle and seize Buda itself. All of this had to be accomplished before the end of October at the latest, if the army was to have sufficient time to return to its winter quarters. Having left Constantinople on the 23rd of April, the massive Ottoman host crossed the Sava on the 21st of July. Six days later, Pétervárad fell to the Turks who brutally sacked the fortress and city leaving, in the words of a contemporary Ottoman chronicler: ”... across the mountains and valleys, in the gardens and granges, like bloodthirsty dogs and wolves, catching the spawns of hell like lions, leaving nothing for the evil of the natural enemy, no plains, no houses on the mountains, no fields, their own property and the grain necessary for their existence mercilessly destroyed.”[13]

By then King Louis had set his army in motion, leaving Buda on July 20. Marching slowly south along the right bank of the Danube, the royal army was slowly reinforced as the general mobilisation of the rural tenants finally came to effect, blooded swords and arrows being circulated to signal the call to arms. As July gave way to August, Louis commanded a force some 25.000 strong, but the foreign reinforcements were still weeks if not months away. The Hungarians camped briefly at Tolna before arriving at the village of Mohács on the 23rd of August, the very same day the Ottomans forced the Drava at Eszék, leaving that city’s churches smoldering in their wake. The two armies were thus only separated by five days worth of marching.

At the royal war council the following evening, the king argued forcefully for a tactical retreat. In the words of his secretary, the Bishop of Senj, Stephen Brodarics, the realm would “... suffer less damage if the enemy wandered freely over the whole region from Mohács to Pozsony, devastating it with fire and sword, than if such a huge army, together with the king and a great number of lords and soldiers, were killed in one single battle.”[14]

The Mohács-Érd Campaign of 1526.

However, the adherents of Archbishop Tomori, who “believed unshakeably in victory” declared that if the king were to retreat, then they would not attack the Ottomans, but rather the royal encampment![15] It took a considerable effort for the king and his supporters to win over the council and even then many within the army had finally lost whatever remaining faith they had in Louis’ regal ability. According to Brodarics, it was only the timely arrival of Francis Batthyány’s Slavonian contingent which deterred the archbishop’s troops from acting on their threats. More importantly though was probably the news Batthyány brought of Bourbon’s and Ferdinand’s advancing armies.[16] As subsequent events came to prove, the king’s decision was undoubtedly the single-most prudent choice he had made throughout his entire reign. Indeed, scholars and amateur historians have often wondered just what might have happened if Louis II had chosen to give battle at Mohács, although many consider Brodarics’ suggestion that the king and his entire army would have been destroyed to be little more than hyperbolic exaggeration.

On the 25th of August, the army struck its tents and began to withdraw. However, outriders from Süleyman’s Rumelian division under Grand Vizier Makbul Ibrahim Pasha soon caught up with the lumbering Hungarian column as it was crossing the River Sió. At this point, the most bellicose Christian formations under Tomori detached themselves from the main army and deployed for battle.

In the ensuing struggle the Hungarian men-at-arms were mercilessly cut to pieces by the Turks, the fords of the Sió “... running red with the nation’s life blood.” Archbishop Tomori himself fell in the shallow waters, his body being trampled by the hooves of the sipahi cavalry. Yet for better or worse, the stand at the Sió completely dispelled the magnates’ view of the Ottoman army as a giant on clay feet. Although shaken, the main army managed to complete its withdrawal - Ibrahim Pasha halting his men at the crossing in order to await the arrival of the sultan and the main Rumelian and Anatolian armies.

Returning to the abandoned mustering grounds at Tolna on the 2nd of September, Louis was relieved to learn that a combined Imperial-Bohemian contingent under the Count of Salm was awaiting him at Székesfehérvár no more than 50 kms to the north-west.[17] Moreover, Christopher Frankopan’s Croatians had joined forces with Charles de Bourbon’s column and were reported to be in the vicinity of Veszprém. The German army of Archduke Ferdinand, however, had only just reached Pozsony while the whereabouts of John Zápolya’s Transylvanians remained unknown.[18]

Still, with the arrival of the Bohemian, Neapolitan and Croatian forces, Louis’ army now numbered almost 50.000 troops and although some sources suggest that Louis II might have entertained the idea of retreating even further west, even his staunchest allies baulked at the idea of surrendering the capital without a fight. Consequently, the king had no choice but to give battle. Command of the allied host fell to the Duke of Bourbon, who was the only officer with experience in leading armies of such a size. The duke subsequently appointed the Count of Salm, Christopher Frankopan and Francis Batthyány as his deputies.[19] Taking up position near the village of Érd, Bourbon heeded the suggestion of a Polish noble named Lenart Gnoiński to arrange the army’s considerable supply train into a defensive wagenburg behind which the allied troops could be deployed.[20]

Meanwhile, the Sultan’s host descended on the Pannonian Plain like a “... restless sea.”[21] As the Ottomans marched north in the scorching Summer heat, raiding parties reduced many of the cities in their path to smoldering rubble. On the 8th of September, Ibrahim Pasha’s Rumelian timariot cavalry appeared before the walls of Székesfehérvár. However, the city proved too hard a nut for the Turk to crack without artillery and it thus avoided the fate suffered by many other Hungarian settlements, such as Pécs, which “... until recently appeared to be a beautiful garden of roses, had now become a burning furnace, whose smoke flew towards the blue sky.”[22] On the sultan’s orders, Ibrahim simply bypassed Székesfehérvár before joining Süleyman and the Anatolian army two days later at the outskirts of the village of Érd.

Charles de Bourbon had distributed his more than 8000 wagons in a crescent-shaped formation, the barrels of his guns protruding from the wagenburg like martial gargoyles. Behind the linked artillery were the infantry, deployed in three ranks immediately while the 12.000 Hungarian light cavalry under Batthyány acted as a mobile reserve.

By the morning of September 11th 1526, the Turks swept onto the field “... with unfurled banners and an army arrayed in battle order, which terrified the enemy.”[23] Trusting in his numerical superiority and aware that the Christians might receive further reinforcements, Süleyman directed his own batteries to pepper the defenders in preparation for a general assault. However, the Ottoman barrage made only a slight impact on the wagenburg, prompting the sultan to order the timariot cavalry to the front while the akinji troops under Bali Bey and Khosrev Bey prepared to circumvent the allied battle line.

In the centre of the Ottoman battle line, four thousand Janissaries armed with arquebuses were deployed in nine consecutive rows in accordance with the rules of imperial battles. Behind them came another 5000 professional troops wielding bows and melee weapons. As the Turkish infantry began to advance, the 200 large field pieces of the Ottoman batteries began to unleash a hellish barrage, which created several breaches in the Christian wagenburg. Although many Janissaries were cut down by counter volleys from the Hungarian gunners and the few Spanish tercio formations placed at the nexus of the allied army, the iron discipline of the Sultan’s household troops prevented the attack from faltering. Halting a few paces from the Christian, the Janissary gunners under the beylerbey of Rumelia began firing “… row by row.”

Bourbon’s crescent formation might have been tactically sound when it came to countering the Ottoman numbers, but the curvature had the unfortunate effect of preventing his flanks from optimising their cross-fire on the Turks attacking the centre. Soon, a breach wide enough for five men to march through “… shoulder by shoulder” had been created into which the kapukulu troops now stormed. Meanwhile, the light akinji units of Bali Bey and Khosrev Bey were busy trying to circumvent the allied left flank. Seeing this, Francis Batthyány broke ranks and led his light horse in a furious charge, which drove back the Beys’ men in apparent terror, but also dragged the Hungarian reserve away from the safety of the wagenburg. Süleyman immediately committed a substantial part of the Anatolian sipahis to support the akinjis forcing Batthyány’s ill-disciplined riders into a confused rout.[24]

With the Christian left wobbling dangerously and the centre embroiled in murderous hand to hand combat around the breach, Bourbon had to shorten his right flank as more and more reinforcements were siphoned off to stabilize the line. Indeed, the scribe of Ibrahim Pasha, Mustafa bin Dzelal, described the vicious melee of the ruined and burning wagenburg as “… the captured dogs fought until the asr prayer with a victorious army and since the cursed people had rifles, many Muslims became martyrs.”[25]

Miniatures from the Süleymanname, second half the 16th century. On the left, King Louis II (depicted as an old weak man, despite being no older than 20) is seated amidst his war council at Mohács. On the right, Sultan Süleyman is depicted surrounded by his household (kapukulu) troops during the Battle of Érd.

Perceiving the entire Christian army to be bound up in the fighting, the Sultan immediately ordered the grand vizier to attack the enemy’s weakened right flank with an immense amount of timariot cavalry. As the sun began to set a temporary lull in the fighting occurred as the Ottomans were preparing for one final assault. Louis II now made his way to Bourbon’s command post and implored him to sound the retreat and withdraw towards the safety of Buda’s walls. It was a crucial decision. The breach in the centre had been momentarily sealed and the kapukulu troops withdrawn, but the right wing was about to give way. Leaving a holding force under Frankopan[26], the Christians fell back in good order, surrendering the field to the Turks.

The Battle of Érd marked a watershed in not just Hungarian, but in Western history as a whole. Although widely considered a tactical defeat, the forces of Christendom had essentially managed to stall the hitherto unstoppable onslaught of the Sublime Porte and caused up to 20.000 casualties in the process. Still, even in this sense, it was naught but a pyrrhic victory. The discipline, organisation and equipment of the Ottoman army had proven their merit and successfully displaced a large and well-led army from a strong defensive position. The more than 15.000 dead Hungarian, Bohemian, Spanish and Croatian troops strewn across the field being a testimony to this fact.

Exhausted and furious at the resistance encountered, the Turks subsequently looted the battlefield, slaughtered the wounded and enslaved whatever captives remained. Two days later, Süleyman appeared before the walls of Buda, apparently intent on placing the city under siege. It would not have been an improbable prospect. In a catastrophic instance of negligence, the government had not secured sufficient provisions to feed the defenders of the capital. Most of the grain and supplies from the harvest had gone south with the army and were now in the hands of the Ottomans, leaving the civilian populace and the close to twenty thousand troops on the brink of starvation.

Fortunately for the defenders, the standards of Archduke Ferdinand were spotted from the ramparts only three days after the battle. Amalgamating his host with some of the dispersed survivors of the allied army, Ferdinand was now poised to take the weary and disgruntled Turks in the rear. Already imperial cavalry columns under Philip of Hesse[27] were raiding the Ottoman picket lines and scattering the sultan’s provisioning parties. Faced with the prospect of facing a battle on two fronts and satisfied that he had sufficiently subjugated the Hungarians, Süleyman decided to retreat on the 16th of September.

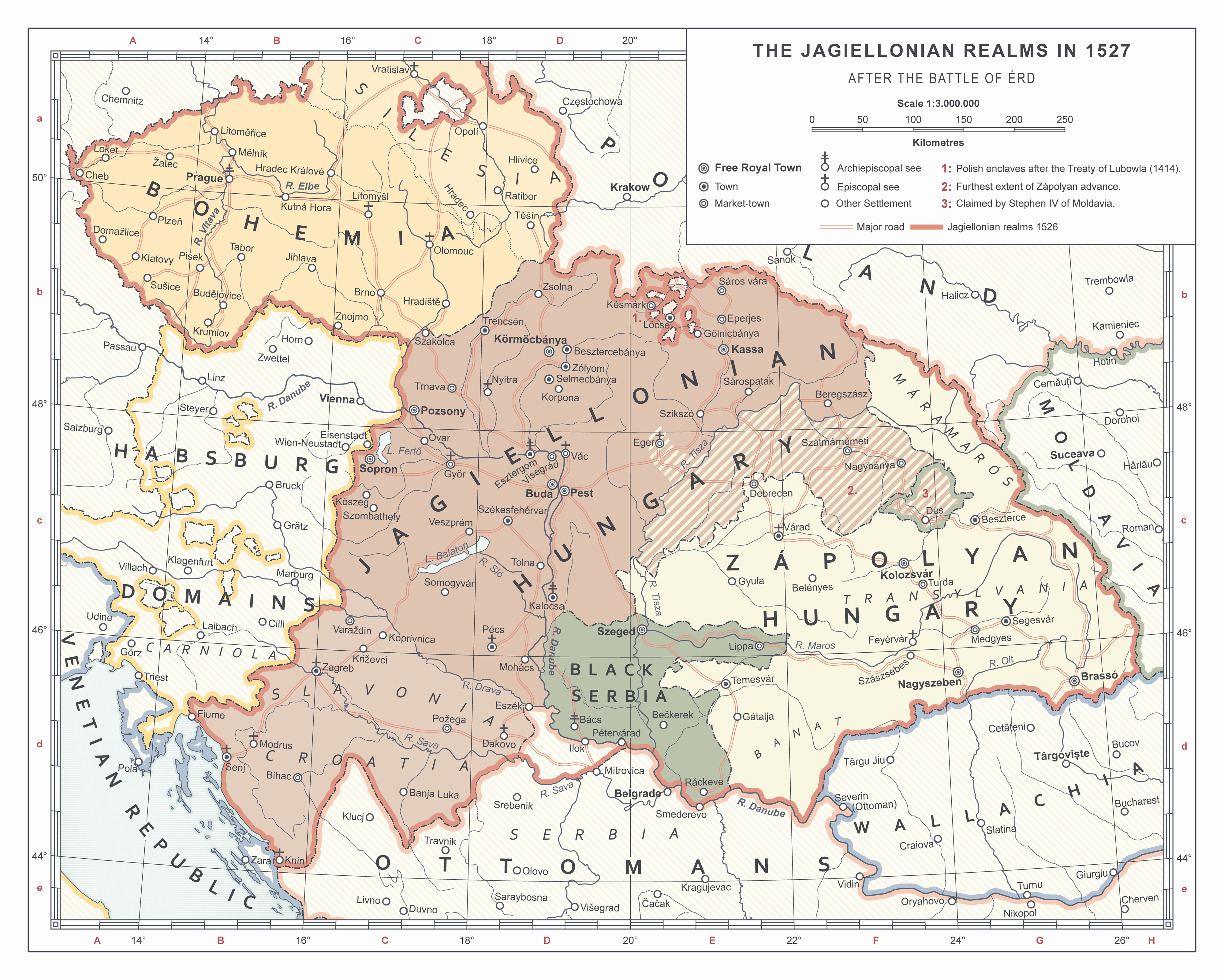

Two days later, Ferdinand and Philip entered Buda to the tumultuous cheers of its inhabitants. In the words of a later commentator “… no army was ever cheered so much for having fought so little.” Besides saving the Hungarian capital, the arrival of the imperial army had profound effects on the domestic politics of the Realm of St. Stephen. The ‘German’ Party of Queen Mary and her supporters was now in the ascendant and Louis II spared little time in securing the crown’s newfound prerogatives. Nobles and commoners who had defied royal authority during the march to Mohács were fined or imprisoned, the proceedings culminating with an official charge of treason being levied against John Zápolya for his tardiness at coming to the king’s aid.

The voivode learned of the royal summons at his camp near Eger and was by all accounts furious at the perceived injustice of Louis’ accusations. Although many historians have argued that Zápolya had indeed intended to assume a position not unlike that of the Baron Stanley at Bosworth, the sources vindicate him to a certain extent. While the king had ordered him to leave Transylvania as late as July, this had been followed by vague or nonsensical counter-orders and credible reports of Ottoman troop movement in the Carpathians. Although subsequent events would inadvertently give the treason charge a veneer of credibility, it is generally agreed that the attainder of John Zápolya was primarily motivated by Queen Mary’s ambition to further curb the power of her political rivals at court and a desire to obtain some the voivode’s immense wealth.[28]

However, Zápolya had no intention to surrender neither himself nor his wealth to the crown’s so-called justice. Rather, he withdrew with his 15.000 men to the market-town of Debrecen to await Louis’ response. Concurrently, he called for a diet to be held at the same place and soon gathered a prominent following of nobles dissatisfied with the crown’s growing power and the king’s supposed bumbling of the Mohács-Érd campaign. It soon became apparent that the court had gravely miscalculated its reach since none of the allied armies showed any interest in pursuing either the Turks or the steadily growing forces of the League of Debrecen. By the middle of October, Süleyman had returned to Belgrade after having garrisoned and fortified the burnt-out husks of Eszék, Ilok and Pétervárad. To the imperial commanders, their campaign had been a success: The Ottomans had been driven off and Hungary saved from the scourge of God. Despite all the camaraderie obtained between the cross-confessional German nobles and troops, the question of church reform continued to hover over the waters and neither side wished to risk their strength in an expensive and dangerous offensive across the Danube. Consequently, the imperial army returned to Germany by the end of November, bringing with them Bourbon’s auxiliaries and a solid part of the remaining Bohemians. Being well-informed by his supporters in the capital, Zápolya now seized the moment. On the 1st of December 1526, the voivode declared Louis II deposed on account of his tyrannical governance, supposed “deference to the Turk” and wanton disregard of the realm’s ancient Scythian Liberties. Civil war had finally broken out.

The Jagiellonian Realms in 1527 after the Battle of Érd. The Ottoman invasion was a costly affair, but in the end none paid a higher price than the peasants and commoners of the realm. The southern reaches in particular were devastated by Süleyman's harrowing with some areas appearing as outright deserts.

Anarchy soon spread across the realm. In the devastated southern reaches of Syrmia, a Serbian regimental leader called Jovan Nenad styled “the Black” gathered a considerable following of local Serbs and dissatisfied Wallachians from the Banat. By early 1527, Nenad had seized the royal free town of Szeged and expanded his influence as far east as the market-town of Lippa, effectively establishing a government independent of either Hungarian faction. Across the length and breath of 'Black Serbia' Jovan was hailed as a saviour, a biblical prophet of the captive Serbian populace, Catholic as well as Orthodox, who promised to restore the medieval Serbian state and drive out Turk and Magyar alike. [29]

The waters were muddied even further when Zápolya’s young lieutenant Bálint Török de Enying reported increased Moldavian military activity along the mountainous border. Besides his princely title, Stephen IV of Moldavia also held a number of Transylvanian fiefs as a vassal of the Hungarian king and now seemed determined to unite his domains on both sides of the Carpathians.

There was little King Louis II could do to counter any of these developments. The royal treasury remained as empty as before the campaign, despite the windfall of confiscations and the royal army had suffered the lion’s share of the casualties incurred at Érd. Fortunately, a substantial number of loyal noblemen had survived the battle including Francis Batthyány, the Judge Royal John Drágfi and the Palatinate Stephen Báthory.

For his part, Süleyman was exceedingly pleased when news reached him of how events were unfolding in Hungary. With the conquests of Pétervárad and Eszék, the Ottomans now possessed a “…high-way of invasion” with its base anchored on Belgrade. Furthermore, the onset of civil war and state dissolution effectively removed Hungary as a tangible Habsburg asset and ensured that the Ottomans’ western border would not be threatened in the foreseeable future: An important development for the sultan, as missives increasingly seemed to indicate that the Persian Safavid dynasty was preparing to resume hostilities in Mesopotamia.

It is generally agreed that the Ottoman invasion of 1526 constituted something of a near-death experience for the Hungarian state. Indeed, regardless of whether or not events could have unfolded even more disastrously (as suggested to by Brodaric), the Mohács-Érd campaign exposed just how painfully fragile the Jagiellonian dynasty had become. In many ways, its survival hinged on the intervention of Archduke Ferdinand, but even then, the Magyar magnates continued to agitate against “… undue German influence” at court. In the words of a contemporary scholar, the nobility “… dreamt of Matthias Corvinus’ empire, but without Corvinus’ reforms.”[30] In other words, the barons were happy to have the Habsburgs at hand when it came to driving off the Turks, but Queen Mary’s much needed attempts at increasing the crown’s authority were anathema to their regimen politicum convictions.

The “restless sea” had thus not just exposed how vulnerable the Realm of St. Stephen was to external pressure, but also unleashed the flood-gates of civil war that had been close to bursting ever since the Peasant War of 1514. As mentioned above, the only one to truly walk away from the 1526-campaign with a smile on his face, was Sultan Süleyman. Hungary had, in effect, been rendered prostate before him. Were he to throw his support behind John Zápolya, the whole kingdom could very well be on its way to desert the Habsburg orbit in favour of Constantinople. As the realm descended into anarchy with prophets and princes fighting for supremacy, the only thing becoming clearer by the day was the fact that Hungary’s destiny was no longer its own.

Author’s Note: This was a really difficult chapter to write. I spent *months* on getting the map of Hungary right alone! I hope you enjoy this update, which literally required blood, sweat and tears to finish and forgive me if we never ever again return to events specific to the Realm of St. Stephen.

[1]This was also the case in OTL: Especially the network of informers in Ragusa proved particularly useful to Tomori.

[2]It’s difficult to overstate the degree of mutual distrust, financial ruin and political dissolution which permeated the Hungarian realm in the late Jagiellonian period. The quote is from an OTL statement made by the Hungarian lords during the mobilisation debacle of 1526.

[3]An OTL statement made by Bakić. While there was little doubt that the Ottomans would strike sometime in 1526, reports were confused and contradictory as to which route the Turks would take into Hungary. Indeed, one of the reasons Ferdinand did not act more decisively in OTL was the breakdown in communications between himself and Louis II.

[4]From an OTL message from Louis II to John Zápolya in July 1526.

[5]Also OTL. For comparison’s sake, the royal Hungarian army only numbered 4000 troops by the Spring of 1526.

[6]The actual size of the Ottoman invasion force is still debated with figures ranging from 50.000 to 300.000. Based on the sanjak lists of mobilisation for the 1526 campaign it has been estimated that 45.000 timariot cavalrymen and 15.000 professional (kapukulu) soldiers from all over the empire were assembled. To this we should add a large amount of irregulars, which I’ve conservatively set to 20.000, thus bringing the total Ottoman strength in April 1526 up to 80.000.

[7]OTL quote attributed to Tomori on the eve of the Battle of Mohács.

[8]This also happened in OTL before Mohács.

[9]Despite the claims of older scholarship, Ferdinand was in no way indifferent to the events unfolding in Hungary. As early as April 30th 1526 (a week after Süleyman left Constantinople) he appealed to his brother for funds to field an army of 18.000 men to help the Hungarians.

[10]This also happened in OTL, but seeing as the Diet of Speyer in TTL succeeded at mellowing the confessional waters even further, the imperial Estates grant a much larger stipend and at an earlier point. Count Nicholas was a very able and seasoned soldier who had fought against Charles the Bold and would wind up leading OTL’s defense of Vienna in 1529.

[11]After TTL’s Battle of Gravelines, Charles V began assembling an army in Naples to attack the French in Milan (see Chapter 27). However, despite the imperial success in northern France, de Lannoy has not received any order of advance. Faced with the prospect of invading the Papal States, he instead chooses to aid Ferdinand in Hungary.

[12]From an OTL letter to Louis II penned by Pál Tomori, 1526.

[13]From the OTL description of the campaign by the contemporary Ottoman chronicler and historian Kemalpaşazâde.

[14]We know from Brodarics’ account that a tactical retreat was seriously considered in OTL.

[15]This actually happened in OTL as well.

[16]While it is impossible to say whether or not Brodarics’ description of events was shaped by the power of hindsight, the royal suggestion of retreating wins through ITTL thanks to 1) the tangible prospect of reinforcements from the Empire, Bohemia and Italy and 2) Queen Mary’s marginally better handling of the proscription of the Magyar Party as described in Chapter 27.

[17]By the time of the Battle of Mohács in OTL (29th of August), the Bohemian contingent had already reached Székesfehérvar.

[18]The voivode had in fact, as in OTL, left Turda on the 18th of August but was still weeks away from the main theatre of operations.

[19] At Mohács in OTL, the Hungarian commanders Pál Tomori and George Zápolya only accepted their position with much reluctance. Indeed, most Hungarian military officers at this point were only experienced in conducting kleinkrieg operations and raids.

[20]This was also proposed by Gnoiński (who acted as a sort of chief-of-staff of the royal army) in OTL, but dismissed by the Hungarian war council as ‘impractical’. Having seen the Ottoman military meat mincing machine in action, the allied coalition is much more predisposed to taking a defensive position. This is an important change, because the Hungarian army was surprisingly well-supplied with artillery. In total, the army commanded 85 greater cannons, ca. 500 smaller pieces (the so-called Praguer hook-guns) while a majority of the 10.000 strong infantry division was armed with arquebuses. If a defensive wagenburg position had been adopted (5000 wagons were available in OTL), the Hungarian firepower would probably have gone a long way in countering the immense Ottoman numerical superiority. This also dispels the traditional view that Mohács was a battle fought between a modernised Ottoman army and a traditional, feudal Hungarian army.

[21]From Kemalpaşazâde’s (very poetic) description of Süleyman’s Hungarian campaign.

[22]Ibid., although the description originally referred to the sack of Bács in October 1526.

[23]OTL quote about the Ottoman army at Mohács.

[24]At Mohács, Batthyány’s cavalry did break through the Ottoman line (constituting the only successful Hungarian attack of the battle), but squandered their advantage by plundering the enemy camp instead of pursuing the Turks.

[25]This OTL quote by bin Dzelal actually refers to the events during the sack of Pétervárad in July 1526.

[26]Frankopan was the hero of an ill-fated 1525 campaign against the Turks and had volunteered to lead the army at Mohács, although his OTL arrival occurred too late for him to take command.

[27]The Landgrave was a very martial man and would undoubtedly have wished to partake in the cross-confessional expedition against the Turks.

[28]John Zápolya was by far the richest man in all of Hungary.

[29]This happened in OTL as well.

[30]This is a slightly rewritten quote by the Hungarian historian Pál Engel as cited in Tamás Pálosfalvi’s “From Nicopolis to Mohács: A History of Ottoman-Hungarian Warfare, 1389–1526” (which incidentally is also an excellent book and one of my main sources for this chapter).

Last edited:

An absolutely magnificent update. I really enjoy the spin on Mohacs this time around. It is a bit funny how perspectives change when you try to contrast these sorts of events to their OTL counterparts. I am not entirely sure, but I actually think that this result might be more beneficial to the Ottomans than the OTL sequence of events - Hungary is removed as a formidable force on the northern border, instead splintered by civil war and effectively removed from the Habsburg arsenal. It replaces the OTL constant back-and-forth with what is essentially a greatly weakened buffer state and allows the Ottomans to concentrate their resources more directly on whatever ongoing trouble spot they seek to deal with.

The amount of work and research put into this is incredible - knowing how difficult it is to find from my own TL experiments with this period, the level of detail you are able to draw out is frankly disgusting. This remains my favorite TL in the pre-1900 forum and I can't wait to see what more you have in store for us.

The amount of work and research put into this is incredible - knowing how difficult it is to find from my own TL experiments with this period, the level of detail you are able to draw out is frankly disgusting. This remains my favorite TL in the pre-1900 forum and I can't wait to see what more you have in store for us.

So, Mohacs is butterflied! And no Habsburg Bohemia and Hungary... Very interesting stuff! I wonder if we end up in a situation with Zapolya Hungary and Jagiellon Bohemia

And as always, a very lovely update I’m always overjoyed when this TL shows notifications hahah

I’m always overjoyed when this TL shows notifications hahah

And as always, a very lovely update

Incredible. Will we at least get to find out if Louis is able to keep his throne?

excellent chapter! it was brilliant how you butterflied Mohacs yet still not fixing Hungary. while it is sad to see the anarchy unfold it will be fascinating to watch, so basically Hungary in the foreseeable future will be like the PLC in the 18th century?

An absolutely magnificent update. I really enjoy the spin on Mohacs this time around. It is a bit funny how perspectives change when you try to contrast these sorts of events to their OTL counterparts. I am not entirely sure, but I actually think that this result might be more beneficial to the Ottomans than the OTL sequence of events - Hungary is removed as a formidable force on the northern border, instead splintered by civil war and effectively removed from the Habsburg arsenal. It replaces the OTL constant back-and-forth with what is essentially a greatly weakened buffer state and allows the Ottomans to concentrate their resources more directly on whatever ongoing trouble spot they seek to deal with.

The amount of work and research put into this is incredible - knowing how difficult it is to find from my own TL experiments with this period, the level of detail you are able to draw out is frankly disgusting. This remains my favorite TL in the pre-1900 forum and I can't wait to see what more you have in store for us.

I think it’s more complex, if the Hungarians are permanent weaken the Ottomans will make a move to conquer Hungary again, while if the king wins he will likely break the nobility and set up a proto-absolute state up. This would leave Ottomans with a stronger Hungary with good relationship with the emperor meaning the Hungarians can always focus on the Ottomans.

Absolutely incredible work, as always. Interesting that the Ottomans don't seem to be actively backing Zapolya, but to be honest it might make more sense to play the one against the other if you're hoping to weaken Hungary sufficiently for conquest.

Also, being entirely pedantic, but this sentence doesn't make sense:

Also also, your maps are as beautifully drawn as ever.

Also, being entirely pedantic, but this sentence doesn't make sense:

excellent spy network of

Also also, your maps are as beautifully drawn as ever.

As always, I'm glad to see the excellent writing -- and excellent mapmaking -- of this TL return.

Stephen Brodarics is clearly the smartest man in Hungary, especially when one has the OTL hindsight of what happened at Mohacs. The Hungarian elite, IOTL as ITTL, is outright delusional -- and Louis II is a) not as able as Bela II, who saved Hungary from total destruction by the Mongols, and b) tied to a Bohemia that is already old hand at the coming century of religious strife. Even compared to other examples -- like the Portuguese before Alcacerquibir or the late-stage Polish szlachta -- they seem hellbent on crippling the realm for their own personal benefit. It's incredible how the pendulum swung from Corvinus to this -- and as others have pointed out upthread, this prolonged civil war and furthering hollowing-out of Hungary may well be worse than the swift decapitation of IOTL.

I'm rooting for the quixotic rebels of Black Serbia (as opposed to Montenegro, the other black Serbia) -- and I have to wonder how long the Croats will tolerate this collapse of royal authority and regional security before entertaining a revival of the Crown of Zvonimir (perhaps given to the ascendant Germans?) As Zulfurium also points out, the Ottomans are not yet tied down officially in Hungary -- perhaps Black Serbia or Croatia will become a Phanariot-run puppet state, and the Vlachs will instead be subjected to direct rule from Constantinople? With the Russians doing better against Kazan, a direct land connection to the Crimean Khanate may be more necessary than IOTL.

I also have to wonder what play the Bohemians will go for, especially given the advent of Protestantism. Without the direct Habsburg inheritance, and with their tradition of selecting kings instead of firm primogeniture, I'd guess that it is more likely that the Bohemian crown will (eventually) go to a Protestant German prince as opposed to the Habsburgs - the directly neighboring Saxon Wettins make sense, as does the House of Brandenburg.

Stephen Brodarics is clearly the smartest man in Hungary, especially when one has the OTL hindsight of what happened at Mohacs. The Hungarian elite, IOTL as ITTL, is outright delusional -- and Louis II is a) not as able as Bela II, who saved Hungary from total destruction by the Mongols, and b) tied to a Bohemia that is already old hand at the coming century of religious strife. Even compared to other examples -- like the Portuguese before Alcacerquibir or the late-stage Polish szlachta -- they seem hellbent on crippling the realm for their own personal benefit. It's incredible how the pendulum swung from Corvinus to this -- and as others have pointed out upthread, this prolonged civil war and furthering hollowing-out of Hungary may well be worse than the swift decapitation of IOTL.

I'm rooting for the quixotic rebels of Black Serbia (as opposed to Montenegro, the other black Serbia) -- and I have to wonder how long the Croats will tolerate this collapse of royal authority and regional security before entertaining a revival of the Crown of Zvonimir (perhaps given to the ascendant Germans?) As Zulfurium also points out, the Ottomans are not yet tied down officially in Hungary -- perhaps Black Serbia or Croatia will become a Phanariot-run puppet state, and the Vlachs will instead be subjected to direct rule from Constantinople? With the Russians doing better against Kazan, a direct land connection to the Crimean Khanate may be more necessary than IOTL.

I also have to wonder what play the Bohemians will go for, especially given the advent of Protestantism. Without the direct Habsburg inheritance, and with their tradition of selecting kings instead of firm primogeniture, I'd guess that it is more likely that the Bohemian crown will (eventually) go to a Protestant German prince as opposed to the Habsburgs - the directly neighboring Saxon Wettins make sense, as does the House of Brandenburg.

Magnificent as always. The level of detail. I'll basically need to reread Chapter 27 just to appreciate some of the small things. In awe of the amount of research. Hard to find anything comparable, especially when they're focusing on a region not the center of their TL.

I really love how not suffering the catastrophic Battle of Mohacs doesn't mean that things are good. Mohacs largely happened due to serious underlying issues in the Hungarian state, and losing less spectacularly surely doesn't change that. Too often TL's will have such a monumental battle go the other way, and it seems everything starts trending better. I'm going to say this civil war won't be ending anytime soon.

I'll put out a guess though that Zapolya will probably win most of Hungary. His rhetoric will simply be more appealing to the nobles, and he'll probably only realize the shitty position he put himself into when he's the one suddenly holding royal authority. The Jagiellons will probably retreat to Bohemia. I could see the Habsurg's somehow all but making Croatia a vassal somehow. As the Jagiellons will likely hold onto their claims to Hungary and the Haburgs will want Hungary retaken, I sort of imagine Hungary will instead become a bugger state between the Habsurg's and Ottomans. Technically independent, but honestly not able to challenge anyone in either direction without the aid of the other.

I really love how not suffering the catastrophic Battle of Mohacs doesn't mean that things are good. Mohacs largely happened due to serious underlying issues in the Hungarian state, and losing less spectacularly surely doesn't change that. Too often TL's will have such a monumental battle go the other way, and it seems everything starts trending better. I'm going to say this civil war won't be ending anytime soon.

I'll put out a guess though that Zapolya will probably win most of Hungary. His rhetoric will simply be more appealing to the nobles, and he'll probably only realize the shitty position he put himself into when he's the one suddenly holding royal authority. The Jagiellons will probably retreat to Bohemia. I could see the Habsurg's somehow all but making Croatia a vassal somehow. As the Jagiellons will likely hold onto their claims to Hungary and the Haburgs will want Hungary retaken, I sort of imagine Hungary will instead become a bugger state between the Habsurg's and Ottomans. Technically independent, but honestly not able to challenge anyone in either direction without the aid of the other.

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 37 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 26: White Rose Victorious Chapter 27: The One Good Harvest Map of Denmark and Schleswig at the End of the Late Medieval Period (ca. 1490-1513) Chapter 28: On the Shores of a Restless Sea Chapter 29: A Thorny Olive Branch Chapter 30: Via Media Chapter 31: The Garefowl Feud Chapter 32: The Queen of the Eastern Sea

Share: