You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Story of a Party 2.0

- Thread starter Utgard96

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Story of a Party - Chapter XXX

Assorted American Affairs

"What white man can say I ever stole his land or a penny of his money? Yet they say that I am a thief."

- Attributed to Sitting Bull

***

From "The Indian Wars of the Nineteenth Century" by Anthony Wilkinson

Anagram Press, Philadelphia, 1994

The Great Lakota War of 1877, as with so many other conflicts throughout human history, can largely be traced back to the previous conflict between the Sioux and the United States government. Red Cloud's War of 1868 had seen a rare Indian victory over the U.S. forces, and the resulting Treaty of Fort Laramie saw a large portion of western Dakota Territory set aside for Sioux use. However, with the rapid western expansion that came after Reconstruction, there was much pressure on the Lakota to counter-cede land back to the whites, and when the Custer Expedition of 1874 found gold in the Black Hills, settlers poured into the region in a clear violation of the treaty. The United States Army initially tried to keep settlers out of the treaty reservations, but failed miserably in this, and in the spring of 1865, the infuriated Sioux leaders travelled to Washington, D.C. to plead for their people. They met with President McPherson, Secretary of the Interior Amos Akerman, and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Quincy Smith, who suggested that the Sioux would be paid $25,000 for the Black Hills and relocated to the Indian Territory. The Sioux naturally refused, their delegation leader Spotted Tail exclaiming that "if it is such a good country, you ought to send the white men now in our country there and let us alone."

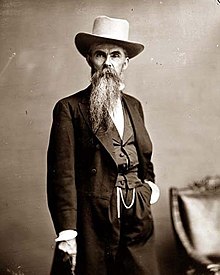

Sitting Bull, war chief of the Lakota confederacy.

After this fiasco, the government sent an expedition to try and win the Sioux people's support, and put pressure on the tribe's leaders to evacuate. This was a dismal failure, and only made relations between the two groups worse. Along with the Black Hills issue, the Northern Pacific was being chartered in the fall of 1875, and the route proposed by the government traversed some of the last remaining Sioux buffalo hunting grounds. To Washington's ire, those Indian groups (both Sioux and Northern Cheyennes) who weren't party to the treaty had also strayed beyond the reservation, and this issue became a running sore for the following months. Both sides began to prepare for war; the U.S. Army leadership felt that an unprovoked attack would lead to more conflict with other tribes in the future, whereas the Sioux felt it was too late in the year to commence a war, as the buffalo hunt had just begun. As such, the government sent an ultimatum to the Sioux war chief Sitting Bull, requesting that the non-treaty bands of Sioux move back into the reservation, with the threat of war should Sitting Bull fail to comply before January 31. The local Indian agency protested the early deadline, as the harsh winter made it difficult to communicate, but nothing was done to rectify it, and as no answer had been received by the end of January, the U.S. Cavalry was ordered in.

The war plan called for three columns of troops, coming out of Forts Mansfield [1], Fetterman and Fremont [2], to converge on the hunting grounds, leaving no route of escape. The Fetterman column was the first to make contact with the Sioux, meeting them in battle at Crazy Woman Creek [3] on June 3. Though the U.S. forces claimed a victory, they were severely checked by the fight, so most modern historians argue it was a draw, if not an Indian victory. Colonel Custer's western column met up with the Sioux at the Little Bighorn, where they managed to score an upset victory, one of few battles in the war to end favourably for the government forces.

George Armstrong Custer in 1863, during his service in the occupied South.

The column coming out of Fort Fremont met with the stiffest resistance; in the Battle of Cherry Creek, the cavalry was decimated by the Sioux forces. Following this setback, the federal government opted to change its strategy; rather than wage a conventional war, they decided to step up troop numbers at the Indian agencies, in order to contain the resisting Sioux and stop them being supplied. In mid-October, the leaders of Red Cloud and Red Leaf villages were taken prisoner, though noncombatant, for failing to apprehend individuals coming from hostile bands. At this point, another commission was sent to the Sioux leadership, who agreed to come to terms.

The resultant treaty, although clearly favouring the government, was not quite as harsh on the Sioux as had been feared earlier. The Black Hills themselves were to be ceded and opened for formal white settlement, and the Northern Pacific was to be given a land grant through Sioux territory, but the railroad was to stay clear of the hunting grounds, and the Sioux were granted the parts of Dakota between the 46th parallel and the Missouri to compensate for the cession. Dakota west of the river was later made a separate territory, and though it did not gain statehood until 1907, the Sioux remain a powerful factor in Hesapa's politics to this day.

***

From "The Worker's Vanguards: A History of U.S. Guild Politics" [4] by Howard Delano

Harper & Sons Publishing Co., New York City, 1967

The end of the Civil War brought about a boom in railroad construction; between the years 1864 and 1870, 49,000 kilometers of track were laid [5]. However, as in so many other cases, this rapid boom came at the expense of workers' rights, and following the stock market crash of 1874, a large number of railroad workers saw their wages slashed as their employers tried to keep their finances in the green in the face of the crashing economy.

In February of 1878, the Baltimore & Ohio made the mistake of cutting its employees' wages for the second time in four months; on February 21, the infuriated workers in Grafton, Vandalia went on strike in protest, refusing to let any rolling stock move until the pay cut had been rescinded. The state governor sent in state militiamen to deal with the situation, but they proved unwilling to engage the strikers, whereupon the governor asked for federal troops. The strike spread quickly across much of the central Alleghenies [6], reaching Pittsburgh within the week. Thomas A. Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad asked the local law to "feed [the strikers] of the rifle diet for a few days, and see how they like that kind of bread"; although the authorities were initially reluctant to engage the strikers, on March 1, Pennsylvania state militiamen bayoneted and opened fire on them, killing twenty-two men and wounding some thirty others.

Maryland National Guardsmen fighting their way through Baltimore.

In Cumberland, Maryland, a conflict between strikers and National Guardsmen led to the strikes spreading through most of that state; it was only after President Fish sent in federal troops to restore order on the streets of Baltimore that the violence in that area ended. By then, Philadelphia's Center City had been mostly set on fire as a consequence of the strikers and militiamen fighting in the streets. The strike reached as far west as East Saint Louis, where several rail yards were shut down by striking workers; the Saint Louis Workingmen's Party sent several of its members across the Mississippi in a show of solidarity with the strikers, and before long, the strikes there expanded into a mass movement among employees of several different industries for a ban on child labor and an eight hour workday reform - the first general strike in American history.

The strike, while massive in scale, only lasted a few weeks; the administration sent in federal troops to city after city, and the strikers generally dispersed after these shows of force. By early April, the strike was mostly over, and railroad workers were forced to return to work without any concession on the employers' part. When the dust had settled, many factors were suggested as determining in causing the strikes; the New York Herald suggested that a Marxist conspiracy was behind it [7], whereas many on the workers' side blamed the lack of guild organisation among the rail workers (the railroad brotherhoods, while playing a small part in the strikes, were still in their infancy at this point, and were barely present in the area where the strike started). There is still no general consensus about why the strikes began, but looking back, one thing is certain: the railroad strike of 1878, while possibly the first big strike in American history, was not to be the last.

***

From "The Rock of Ages: A History of the Unionist Party" by Joseph E. Crater

Unionist Party Publishers, Washington, D.C., 2008

The 1870s were very much a decade of soul-searching for the Unionist Party. What had come about as a party of Upper Southerners who wanted to either make a compromise on slavery or ignore the issue altogether, and grown into prominence as a party of moderates who opposed both the Democratic and Republican stances on Reconstruction, was now a big tent under which dwelt the original Constitutional Unionists, moderate Republicans, former southern Whigs, and several other groupings. The party had lost control of the executive with Curtin's defeat in 1872, and did not regain it for the rest of the decade; however, they did hold the House during most of the Long Depression, riding a wave of discontent with Republican fiscal policy. Following the termination of the greenbacks in 1873, most of the Unionist Party backed a bimetallic currency; the eventual adoption of a wholly-gold currency standard, and subsequent economic collapse, led to the party leadership making this official policy, and the Unionist campaign of 1876 hinged on this issue.

William "Little Billy" Mahone, railroad president and Leveller leader.

Following the end of Reconstruction, the Establishers, who mostly still identified with the defunct Democratic party, took power in nearly all the southern states; however, Virginia saw a period under the control of a loose coalition that opposed the Establisher dominance and sought to create a more equal society. This group, known as the Levellers [8], wanted to abolish the racially biased voter registration system, break the dominance of the planter class, and establish more comprehensive public education. Though the Levellers were not formally affiliated with the Unionist Party, they did inspire Unionist doctrine regarding reconstruction; the party, unlike the Republicans, never explicitly stressed the importance of racial equality (a fact that earned them no love from most northerners), but the ideas of equal representation and the extension of the public sector were later adopted by the Unionist Party.

However, it was another prominent southern faction that was to get inextricably linked with southern Unionism for all time: the Redeemers. The Redeemers, inspired by the relative impoverishment of the post-war South and the great industrial wealth of the North, held that the South should develop its own industry, partly in order to make its economy less dependent on the cotton trade, but mostly to bring the South closer to equality with the North and lessen its dependence upon northern goods [9]. To this end, Redeemer planters reinvested their capital into building up industry, prominently textile mills that could utilise the abundant southern cotton supply and turn it into a finished product. It is important to note that while supporting modernisation of the southern economy, the Redeemers did not support civil rights; newspaperman Henry W. Grady, one of the principal Redeemers, stated that "the supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards, because the white race is the superior race [10]."

Henry W. Grady, prominent Redeemer agitator.

Though the Establishment remained dominant in southern politics, both of its rival ideologies grew in power over much of this time. The Unionist Party, having already absorbed much of Whig doctrine, integrated Redeemer ideas of industrialisation, fair competition, and internal improvements into their platform, and by the early 1880s, a trend was set that would define American politics for decades to come.

***

From "A History of America through its Presidents"

John Bachmann & Son, Bluefields, Nicaragua, 1945

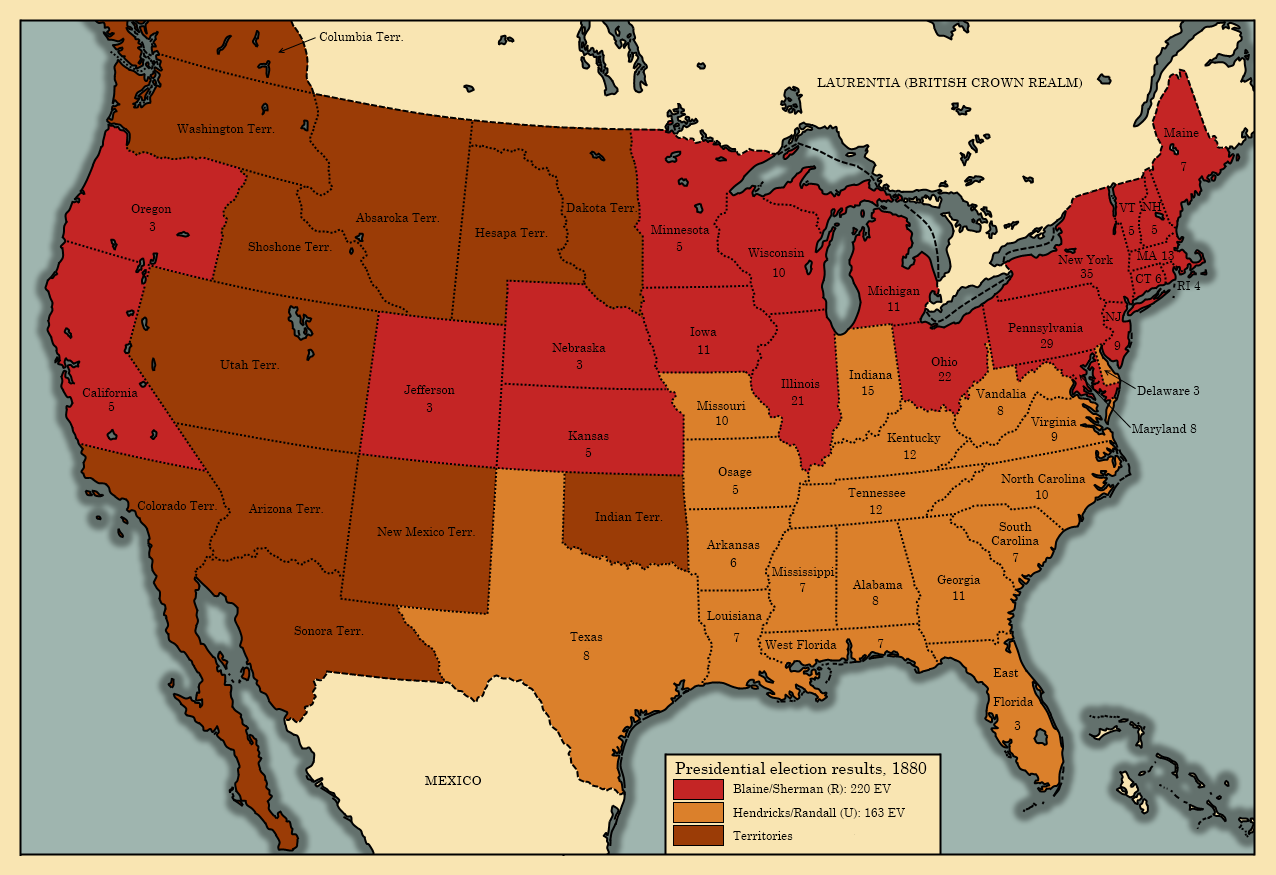

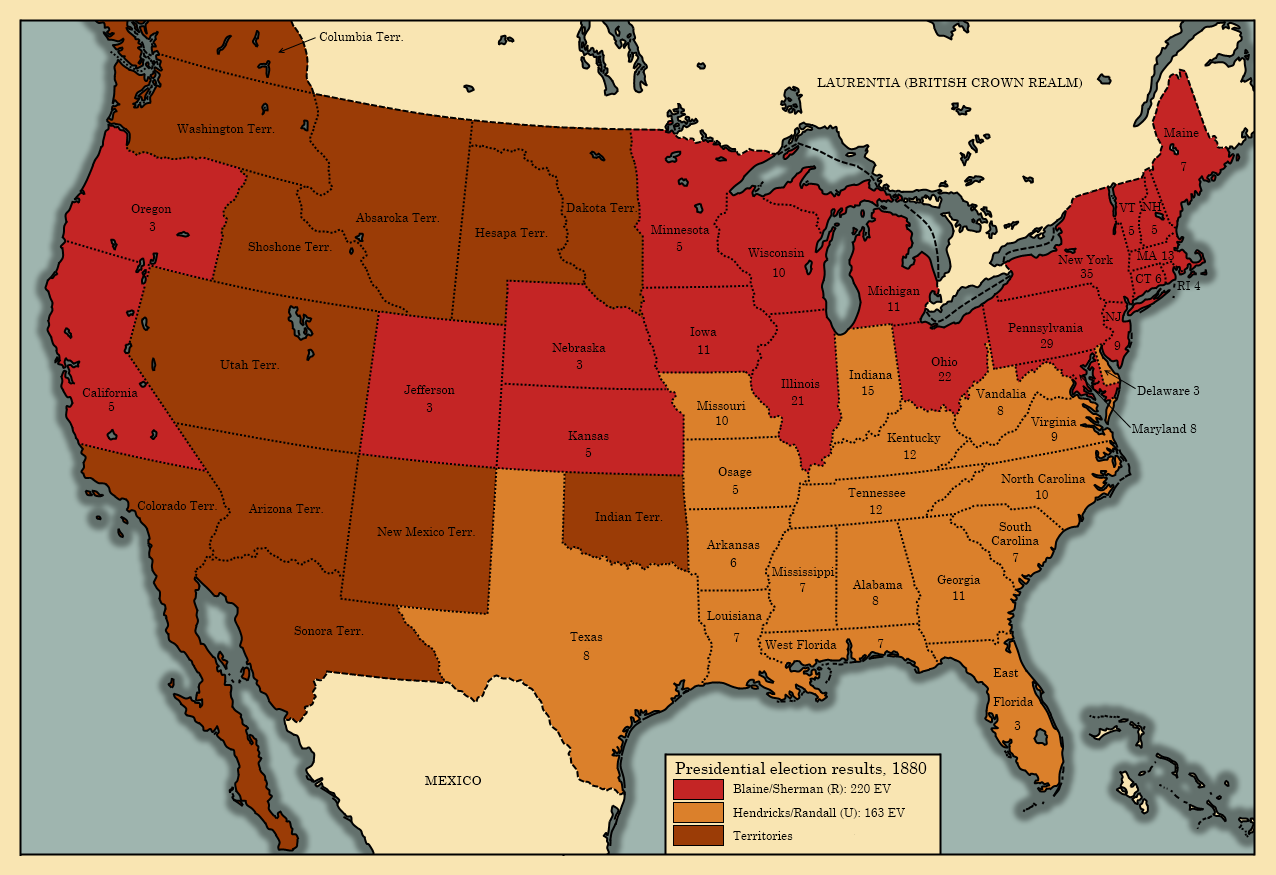

1880 presidential election

The election of 1880, like that of 1876, was marked by the relative peace that had followed the end of Reconstruction. The Long Depression was mostly over, and the economy was entering what was to become one of the longest boom periods in American history. The Republican administration was praised in many circles for its sober handling of the crisis. President Fish and Treasury Secretary Wheeler, in particular, stood out for their actions to resolve the depression, and there were calls for Fish to run for a second term; however, the President declined, citing both his advancing age [11] and an earlier campaign pledge not to run again. Vice President Hayes, for his part, announced in late April that he would retire from politics on the completion of his term.

This left an open race for the Republican nomination, but when the convention had opened, a frontrunner soon emerged: James Gillespie Blaine, newspaperman and senator from Maine [12]. Blaine had authored the Seventeenth Amendment [13] while was an experienced orator, and a noted supporter of black suffrage; however, his relative disdain for the traditional Republican protectionism served to set many radicals against his candidacy, as did his lukewarm attitude toward Jim Crow. Blaine also suffered from his association with several corruption scandals, which worried the party's growing reformist wing. In the end, despite the opposition of portions of the convention, Blaine was nominated, with noted civil service reformer John Sherman of Ohio [14] selected as his running mate in order to balance the ticket.

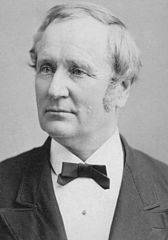

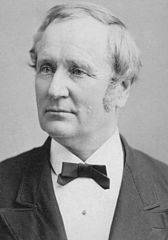

James G. Blaine.

The Unionist convention ended up nominating Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana, who had previously been the Democratic nominee in 1864 [15]; the fact that the party had, in the first twenty years of its existence, only nominated prominent former Democrats and Republicans says quite a lot about its nature in this period. His running mate was Samuel J. Randall of Pennsylvania, a member of the party's small but vocal free-trade faction. What little remained of the Democratic party made no formal nomination, but the various (mostly southern and Establisher) local remnants of the party endorsed the Hendricks/Randall ticket, out of the belief that while far from optimal, the Unionists were at least better than the Republicans.

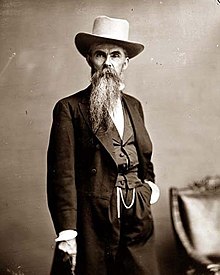

Thomas A. Hendricks.

The race was fairly straightforward - the Republicans managed to ride the wave of popular acclaim for ending the depression, even though the previous Republican administration had played a key part in bringing it about, while the Unionists won many votes by accusing the Republicans of corruption and irresponsibility. In the end, however, Blaine managed to win the election by a relatively wide margin, a victory that can mostly be chalked up to the popularity of the outgoing Fish administration.

***

[1] Fort Mansfield, named for Brig. Gen. Joseph King Mansfield, who died in the Battle of Hanover Courthouse in 1861 (IOTL he was mortally wounded at Antietam), is OTL's Fort Ellis.

[2] Fort Fremont is OTL's Fort Abraham Lincoln.

[3] A name I just had to include somewhere.

[4] Workers' guilds are, ITTL, the common American name for what we in OTL would call trade or labour unions (in Britain, where they were known as this long before the PoD, they're still called trade unions).

[5] The bloodier and more repressive Reconstruction ITTL frees up less government money for such things as railroad subsidies; this is reflected in these figures. IOTL, the figure for equivalent years was 55,000 kilometres of new track.

[6] The "Allegheny Mountains" refers to the entire Appalachian range ITTL; this usage was popular IOTL until about 1880.

[7] New York Tribune: Doin' the McCarthyism before it was hip.

[8] Not to be confused with the English Civil War-era proto-socialist group of the same name. The Levellers were known as the Readjusters IOTL.

[9] This doctrine existed IOTL as well, though it wasn't quite as prominent as it will be ITTL; it was known as the New South Creed.

[10] Grady said this IOTL as well.

[11] Fish was 72 at this point, making him the oldest president in TTL's history so far; this was as old as Reagan was at his second inauguration.

[12] I know this sentence sounds a bit like a Dr. Seuss rhyme. This may or, more probably, may not have significance later on.

[13] TTL's 17th Amendment, which failed to gain traction in Congress IOTL, forbids local governments from giving tax money or public land grants to religious sects.

[14] The elder brother of General William Sherman, Sherman is most famous IOTL for authoring the Sherman Antitrust Act.

[15] Hendricks was, IOTL, one of the most prominent politicians ever to come out of Indiana (meaning no offence to any Hoosiers reading this); he was the first Democrat to be elected governor of a northern state after the Civil War, and was Samuel Tilden's running mate in 1876. He died in 1885, having served as Grover Cleveland's first Vice President for only a few months.

Assorted American Affairs

"What white man can say I ever stole his land or a penny of his money? Yet they say that I am a thief."

- Attributed to Sitting Bull

***

From "The Indian Wars of the Nineteenth Century" by Anthony Wilkinson

Anagram Press, Philadelphia, 1994

The Great Lakota War of 1877, as with so many other conflicts throughout human history, can largely be traced back to the previous conflict between the Sioux and the United States government. Red Cloud's War of 1868 had seen a rare Indian victory over the U.S. forces, and the resulting Treaty of Fort Laramie saw a large portion of western Dakota Territory set aside for Sioux use. However, with the rapid western expansion that came after Reconstruction, there was much pressure on the Lakota to counter-cede land back to the whites, and when the Custer Expedition of 1874 found gold in the Black Hills, settlers poured into the region in a clear violation of the treaty. The United States Army initially tried to keep settlers out of the treaty reservations, but failed miserably in this, and in the spring of 1865, the infuriated Sioux leaders travelled to Washington, D.C. to plead for their people. They met with President McPherson, Secretary of the Interior Amos Akerman, and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Quincy Smith, who suggested that the Sioux would be paid $25,000 for the Black Hills and relocated to the Indian Territory. The Sioux naturally refused, their delegation leader Spotted Tail exclaiming that "if it is such a good country, you ought to send the white men now in our country there and let us alone."

Sitting Bull, war chief of the Lakota confederacy.

After this fiasco, the government sent an expedition to try and win the Sioux people's support, and put pressure on the tribe's leaders to evacuate. This was a dismal failure, and only made relations between the two groups worse. Along with the Black Hills issue, the Northern Pacific was being chartered in the fall of 1875, and the route proposed by the government traversed some of the last remaining Sioux buffalo hunting grounds. To Washington's ire, those Indian groups (both Sioux and Northern Cheyennes) who weren't party to the treaty had also strayed beyond the reservation, and this issue became a running sore for the following months. Both sides began to prepare for war; the U.S. Army leadership felt that an unprovoked attack would lead to more conflict with other tribes in the future, whereas the Sioux felt it was too late in the year to commence a war, as the buffalo hunt had just begun. As such, the government sent an ultimatum to the Sioux war chief Sitting Bull, requesting that the non-treaty bands of Sioux move back into the reservation, with the threat of war should Sitting Bull fail to comply before January 31. The local Indian agency protested the early deadline, as the harsh winter made it difficult to communicate, but nothing was done to rectify it, and as no answer had been received by the end of January, the U.S. Cavalry was ordered in.

The war plan called for three columns of troops, coming out of Forts Mansfield [1], Fetterman and Fremont [2], to converge on the hunting grounds, leaving no route of escape. The Fetterman column was the first to make contact with the Sioux, meeting them in battle at Crazy Woman Creek [3] on June 3. Though the U.S. forces claimed a victory, they were severely checked by the fight, so most modern historians argue it was a draw, if not an Indian victory. Colonel Custer's western column met up with the Sioux at the Little Bighorn, where they managed to score an upset victory, one of few battles in the war to end favourably for the government forces.

George Armstrong Custer in 1863, during his service in the occupied South.

The column coming out of Fort Fremont met with the stiffest resistance; in the Battle of Cherry Creek, the cavalry was decimated by the Sioux forces. Following this setback, the federal government opted to change its strategy; rather than wage a conventional war, they decided to step up troop numbers at the Indian agencies, in order to contain the resisting Sioux and stop them being supplied. In mid-October, the leaders of Red Cloud and Red Leaf villages were taken prisoner, though noncombatant, for failing to apprehend individuals coming from hostile bands. At this point, another commission was sent to the Sioux leadership, who agreed to come to terms.

The resultant treaty, although clearly favouring the government, was not quite as harsh on the Sioux as had been feared earlier. The Black Hills themselves were to be ceded and opened for formal white settlement, and the Northern Pacific was to be given a land grant through Sioux territory, but the railroad was to stay clear of the hunting grounds, and the Sioux were granted the parts of Dakota between the 46th parallel and the Missouri to compensate for the cession. Dakota west of the river was later made a separate territory, and though it did not gain statehood until 1907, the Sioux remain a powerful factor in Hesapa's politics to this day.

***

From "The Worker's Vanguards: A History of U.S. Guild Politics" [4] by Howard Delano

Harper & Sons Publishing Co., New York City, 1967

The end of the Civil War brought about a boom in railroad construction; between the years 1864 and 1870, 49,000 kilometers of track were laid [5]. However, as in so many other cases, this rapid boom came at the expense of workers' rights, and following the stock market crash of 1874, a large number of railroad workers saw their wages slashed as their employers tried to keep their finances in the green in the face of the crashing economy.

In February of 1878, the Baltimore & Ohio made the mistake of cutting its employees' wages for the second time in four months; on February 21, the infuriated workers in Grafton, Vandalia went on strike in protest, refusing to let any rolling stock move until the pay cut had been rescinded. The state governor sent in state militiamen to deal with the situation, but they proved unwilling to engage the strikers, whereupon the governor asked for federal troops. The strike spread quickly across much of the central Alleghenies [6], reaching Pittsburgh within the week. Thomas A. Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad asked the local law to "feed [the strikers] of the rifle diet for a few days, and see how they like that kind of bread"; although the authorities were initially reluctant to engage the strikers, on March 1, Pennsylvania state militiamen bayoneted and opened fire on them, killing twenty-two men and wounding some thirty others.

Maryland National Guardsmen fighting their way through Baltimore.

In Cumberland, Maryland, a conflict between strikers and National Guardsmen led to the strikes spreading through most of that state; it was only after President Fish sent in federal troops to restore order on the streets of Baltimore that the violence in that area ended. By then, Philadelphia's Center City had been mostly set on fire as a consequence of the strikers and militiamen fighting in the streets. The strike reached as far west as East Saint Louis, where several rail yards were shut down by striking workers; the Saint Louis Workingmen's Party sent several of its members across the Mississippi in a show of solidarity with the strikers, and before long, the strikes there expanded into a mass movement among employees of several different industries for a ban on child labor and an eight hour workday reform - the first general strike in American history.

The strike, while massive in scale, only lasted a few weeks; the administration sent in federal troops to city after city, and the strikers generally dispersed after these shows of force. By early April, the strike was mostly over, and railroad workers were forced to return to work without any concession on the employers' part. When the dust had settled, many factors were suggested as determining in causing the strikes; the New York Herald suggested that a Marxist conspiracy was behind it [7], whereas many on the workers' side blamed the lack of guild organisation among the rail workers (the railroad brotherhoods, while playing a small part in the strikes, were still in their infancy at this point, and were barely present in the area where the strike started). There is still no general consensus about why the strikes began, but looking back, one thing is certain: the railroad strike of 1878, while possibly the first big strike in American history, was not to be the last.

***

From "The Rock of Ages: A History of the Unionist Party" by Joseph E. Crater

Unionist Party Publishers, Washington, D.C., 2008

The 1870s were very much a decade of soul-searching for the Unionist Party. What had come about as a party of Upper Southerners who wanted to either make a compromise on slavery or ignore the issue altogether, and grown into prominence as a party of moderates who opposed both the Democratic and Republican stances on Reconstruction, was now a big tent under which dwelt the original Constitutional Unionists, moderate Republicans, former southern Whigs, and several other groupings. The party had lost control of the executive with Curtin's defeat in 1872, and did not regain it for the rest of the decade; however, they did hold the House during most of the Long Depression, riding a wave of discontent with Republican fiscal policy. Following the termination of the greenbacks in 1873, most of the Unionist Party backed a bimetallic currency; the eventual adoption of a wholly-gold currency standard, and subsequent economic collapse, led to the party leadership making this official policy, and the Unionist campaign of 1876 hinged on this issue.

William "Little Billy" Mahone, railroad president and Leveller leader.

Following the end of Reconstruction, the Establishers, who mostly still identified with the defunct Democratic party, took power in nearly all the southern states; however, Virginia saw a period under the control of a loose coalition that opposed the Establisher dominance and sought to create a more equal society. This group, known as the Levellers [8], wanted to abolish the racially biased voter registration system, break the dominance of the planter class, and establish more comprehensive public education. Though the Levellers were not formally affiliated with the Unionist Party, they did inspire Unionist doctrine regarding reconstruction; the party, unlike the Republicans, never explicitly stressed the importance of racial equality (a fact that earned them no love from most northerners), but the ideas of equal representation and the extension of the public sector were later adopted by the Unionist Party.

However, it was another prominent southern faction that was to get inextricably linked with southern Unionism for all time: the Redeemers. The Redeemers, inspired by the relative impoverishment of the post-war South and the great industrial wealth of the North, held that the South should develop its own industry, partly in order to make its economy less dependent on the cotton trade, but mostly to bring the South closer to equality with the North and lessen its dependence upon northern goods [9]. To this end, Redeemer planters reinvested their capital into building up industry, prominently textile mills that could utilise the abundant southern cotton supply and turn it into a finished product. It is important to note that while supporting modernisation of the southern economy, the Redeemers did not support civil rights; newspaperman Henry W. Grady, one of the principal Redeemers, stated that "the supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards, because the white race is the superior race [10]."

Henry W. Grady, prominent Redeemer agitator.

Though the Establishment remained dominant in southern politics, both of its rival ideologies grew in power over much of this time. The Unionist Party, having already absorbed much of Whig doctrine, integrated Redeemer ideas of industrialisation, fair competition, and internal improvements into their platform, and by the early 1880s, a trend was set that would define American politics for decades to come.

***

From "A History of America through its Presidents"

John Bachmann & Son, Bluefields, Nicaragua, 1945

1880 presidential election

The election of 1880, like that of 1876, was marked by the relative peace that had followed the end of Reconstruction. The Long Depression was mostly over, and the economy was entering what was to become one of the longest boom periods in American history. The Republican administration was praised in many circles for its sober handling of the crisis. President Fish and Treasury Secretary Wheeler, in particular, stood out for their actions to resolve the depression, and there were calls for Fish to run for a second term; however, the President declined, citing both his advancing age [11] and an earlier campaign pledge not to run again. Vice President Hayes, for his part, announced in late April that he would retire from politics on the completion of his term.

This left an open race for the Republican nomination, but when the convention had opened, a frontrunner soon emerged: James Gillespie Blaine, newspaperman and senator from Maine [12]. Blaine had authored the Seventeenth Amendment [13] while was an experienced orator, and a noted supporter of black suffrage; however, his relative disdain for the traditional Republican protectionism served to set many radicals against his candidacy, as did his lukewarm attitude toward Jim Crow. Blaine also suffered from his association with several corruption scandals, which worried the party's growing reformist wing. In the end, despite the opposition of portions of the convention, Blaine was nominated, with noted civil service reformer John Sherman of Ohio [14] selected as his running mate in order to balance the ticket.

James G. Blaine.

The Unionist convention ended up nominating Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana, who had previously been the Democratic nominee in 1864 [15]; the fact that the party had, in the first twenty years of its existence, only nominated prominent former Democrats and Republicans says quite a lot about its nature in this period. His running mate was Samuel J. Randall of Pennsylvania, a member of the party's small but vocal free-trade faction. What little remained of the Democratic party made no formal nomination, but the various (mostly southern and Establisher) local remnants of the party endorsed the Hendricks/Randall ticket, out of the belief that while far from optimal, the Unionists were at least better than the Republicans.

Thomas A. Hendricks.

The race was fairly straightforward - the Republicans managed to ride the wave of popular acclaim for ending the depression, even though the previous Republican administration had played a key part in bringing it about, while the Unionists won many votes by accusing the Republicans of corruption and irresponsibility. In the end, however, Blaine managed to win the election by a relatively wide margin, a victory that can mostly be chalked up to the popularity of the outgoing Fish administration.

***

[1] Fort Mansfield, named for Brig. Gen. Joseph King Mansfield, who died in the Battle of Hanover Courthouse in 1861 (IOTL he was mortally wounded at Antietam), is OTL's Fort Ellis.

[2] Fort Fremont is OTL's Fort Abraham Lincoln.

[3] A name I just had to include somewhere.

[4] Workers' guilds are, ITTL, the common American name for what we in OTL would call trade or labour unions (in Britain, where they were known as this long before the PoD, they're still called trade unions).

[5] The bloodier and more repressive Reconstruction ITTL frees up less government money for such things as railroad subsidies; this is reflected in these figures. IOTL, the figure for equivalent years was 55,000 kilometres of new track.

[6] The "Allegheny Mountains" refers to the entire Appalachian range ITTL; this usage was popular IOTL until about 1880.

[7] New York Tribune: Doin' the McCarthyism before it was hip.

[8] Not to be confused with the English Civil War-era proto-socialist group of the same name. The Levellers were known as the Readjusters IOTL.

[9] This doctrine existed IOTL as well, though it wasn't quite as prominent as it will be ITTL; it was known as the New South Creed.

[10] Grady said this IOTL as well.

[11] Fish was 72 at this point, making him the oldest president in TTL's history so far; this was as old as Reagan was at his second inauguration.

[12] I know this sentence sounds a bit like a Dr. Seuss rhyme. This may or, more probably, may not have significance later on.

[13] TTL's 17th Amendment, which failed to gain traction in Congress IOTL, forbids local governments from giving tax money or public land grants to religious sects.

[14] The elder brother of General William Sherman, Sherman is most famous IOTL for authoring the Sherman Antitrust Act.

[15] Hendricks was, IOTL, one of the most prominent politicians ever to come out of Indiana (meaning no offence to any Hoosiers reading this); he was the first Democrat to be elected governor of a northern state after the Civil War, and was Samuel Tilden's running mate in 1876. He died in 1885, having served as Grover Cleveland's first Vice President for only a few months.

Last edited:

James Gillespie Blaine, newspaperman and senator from Maine

Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, The Continental Liar from the State of Maine

Nice update! So, in the spirit of late 19th century corruption, is Fremont going to help me vote for SoaP a second time this year?

I was just re-reading this and something came to mind while looking at a map, Texas: California voted to split up its bottom part into (This TL's) Colorado territory Virginia had Vandalia made from OTL West Virginia, and Osage from Missouri: Will Texas, the then biggest state, undergo anything like that? As I also noticed it gained the strip of Oklahoma above it. Sorry if you mentioned this before.

I was just re-reading this and something came to mind while looking at a map, Texas: California voted to split up its bottom part into (This TL's) Colorado territory Virginia had Vandalia made from OTL West Virginia, and Osage from Missouri: Will Texas, the then biggest state, undergo anything like that? As I also noticed it gained the strip of Oklahoma above it. Sorry if you mentioned this before.

Probably not. Both Virginia and Missouri were split as a result of countersecession, whereas Colorado was created because its inhabitants wanted to split off from California (this came within a hair's margin of happening IOTL). Texas stayed part of the Union ITTL, and AFAIK never had any separation movements to speak of; I may be wrong, but as it looks, Texas is probably going to stay whole ITTL. As for the Neutral Strip, that was ceded to Texas as sort of a reward for staying loyal and accepting abolition (not like what the "freedmen" are going through now is much better than slavery, but still).

As an aside, does anyone know (or know someone who knows) a lot about the Ottomans and the Balkans in this time period? I could use some help with the next update…

I think the Ottomans were starting to lose territory in the Balkans at this time and the Russo-Turkish War.

Story of a Party - Chapter XXXI

Gathering Storms

"Si vis pacem, para bellum." ("If you seek peace, prepare for war.")

- Vegetius, De Re Militari

***

From "The Backyard of Empires: A History of the Balkans, 1850-1916" by Joseph Diefenbaker

Queen's University Press, 2006

To look at the causes of the 1870s uprisings, or indeed those of any such events in the region's history, one must make oneself familiar with the Ottoman Empire, and the state of religious discrimination present in it, as it stood at that point. The Treaty of Paris [1], while purportedly guaranteeing the equality of Christians with Muslims, made little change on the ground. Though the jizya had been abolished, and Christians were allowed to serve in the Empire's military, testimonies by Christians against Muslims were still not admissible in court. This holdout from the old legal system made Muslims impervious to legal action, a fact that encouraged discrimination more than anything else.

Lebanon, 1860.

While the Balkans themselves had been relatively quiet for twenty-five years before the uprisings, other areas under Ottoman rule had seen significant unrest. A peasant revolt in Lebanon in 1860 quickly turned into a religious civil war as Druze and Maronite [2] peasants turned on each other, a situation that turned so volatile that the French intervened to protect the Maronites, and eventually forced the appointment of a Christian governor in the region. Later that decade, a large-scale revolt broke out on Crete, and while this uprising was ultimately unsuccessful in its goals of enosis, or unification, of the island with Greece, this was only so because the Porte gave the island home rule in 1869.

The Ottoman economy was greatly weakened by the cost of fighting these constant rebellions, and in addition, the Empire had to take great pains to accommodate the over half a million Circassians expelled from their homes in the Caucasus by Russia, efforts that not only cost a great deal of money, but also led to large-scale social unrest in the Balkan ports through which the Circassians passed.

The single largest issue that led to the rebellions, however, was nationalism. The allegiance of the national to the nation, of the individual to their homeland and to common ideals of, for instance, Servian-ness far outweighed that of the subject to the ruler, especially when that ruler spoke a different language, held a different set of beliefs, lived a different life in a different place and was more liable to send in the army than to listen to his subjects. Rumania had been a de facto independent state since 1848, as had Servia and Montenegro, but there were large areas of land still under Ottoman control in which the populace identified with these nations rather than with the Empire. The Bulgarians and Bosnians, for their part, were even worse off, as they had no lands to call their own whatsoever.

Although most Bosnians were and are Muslim in belief, the region known as Herzegovina, in the south of the country, was populated mainly by Croats, who were Catholic Christians. Catholics were subject to the same discrimination as Orthodox Christians, and the local authorities encouraged unrest by ignoring the discrimination entirely. In March of 1875, the Christian population of Herzegovina broke out in open rebellion against Ottoman authority, an act that opened the flood gates for half a decade of war across the Balkans.

The revolt, which saw significant support from Serb and Montenegrin volunteers, quickly became a running sore, and a year after beginning it still went on, the Ottomans committing more and more troops to quell it. This spurred the Bulgarians into action, and a large-scale uprising broke out in the Bulgarian-inhabited lands in early 1876. The Ottomans, having few regulars to commit to anything except quelling the rebellion in Herzegovina, were forced to send in corps of bashi-bazouks [3], irregulars in the Sultan's service, to quell the Bulgarian uprising. They did so, moving with extreme brutality, and killing Bulgarian revolvers by the thousands.

This famous painting by Makovsky shows a Bulgarian woman being raped by a bashi-bazouk, a distressingly common sight in 1870s Bulgaria.

The brutality of the bashi-bazouks got out quickly, and upon reaching Western Europe, many people there sharply decried the events. The Serbs, for their part, were even more incensed at the slaughter of the rebelling Bulgarians; on June 30, they declared war on the Ottomans. They were supported by Montenegro and by Russian volunteers, and thanks to their broad base of support they were able to fend off the Ottoman army as it invaded. However, in doing so, the Servian army's already meagre strength was severely checked, and they failed to achieve any of their original objectives. Knowing that another attack would likely destroy them, the Serbs asked the Western powers to mediate a truce. The West agreed, and a ceasefire was declared in early September; however, the Turkish terms were not accepted by either the Serbs or the mediators, and so the war went on.

The Ottoman army resumed its offensive as October arrived, and the Servian position became more and more desperate. It was then that the Russian behemoth decided to act, and on October 31, St. Petersburg sent an ultimatum to Constantinople, demanding that they cease the war with Servia. The Russian army was mobilised to back the ultimatum, but the Porte refused to budge. The war had begun [4].

***

From "The Juggernaut of the East: Russia's Army in the 19th Century" by Jérôme Saint-Laurent

Translated into English by Michael Henderson

Schulman Publications, Birmingham, 1999

Immediately after the declaration of war, the Army of the Danube crossed the Prut into Rumania; then-Prince Amadeu had already pledged his support for the Russian side, hoping to gain complete independence from the Ottomans.

The outcome of the war, contrary to what is generally assumed by outside (and especially Russian) observers, was far from guaranteed at the outset; while Russia had a much larger force than the Ottomans (sources estimate that roughly 300,000 troops were within reach of the Balkans at the start of the war, compared to the 120,000 Turkish troops in the region not assigned to garrison duty). However, the Ottomans had better fortifications, naval superiority over the Black Sea and much of the Danube, and most importantly, better equipment. Many Turkish infantrymen were issued the iconic M1874 Henry rifle [5] of American design, and several German Krupp guns were used by the artillery.

The Russian army crossing the Danube.

The major weakness in the Ottoman defence was that they underestimated the Russian strategy; thinking the Russians too lazy to march around the fortifications and strike further up the Danube, they manned their fortifications in the Dobruja fully, leaving only a few troops in the west save for those invading Servia. When the Russian army did cross the river in January of 1877, it did so at Svishtov, thirty miles west of Ruschuk. The Russians had spent much of the preceding months mining the river and gunning down Turkish patrol boats, and after a brief battle, a bridgehead was secured. The Russian army was organised into three forces; one would advance south, toward the Balkan Mountains themselves, while one would watch each flank of the first force's movement.

The Porte responded by sending Osman Nuri Pasha with 18,000 men east from Vidin to the fortress of Nikopol, at the mouth of the Olt, where they arrived on February 2 [6]. The Russian western flank, already on its way to Nikopol, engaged the Turks almost immediately, and although the numbers were close, managed to score a victory, taking the fortress and denying a large stretch of the Danube to Ottoman control. Plevna was captured soon after, following a brief siege [7], and the Russian march south continued.

The Porte had already sent a second army of 30,000, commanded by Suleiman Pasha, to attack the Russians head-on from the south; this army crossed the Balkans at Shipka Pass on February 7 [8], and moved north, reaching the old Bulgarian capital of Tarnovo on the 9th. The Russians were engaged at Vodolei on the 12th; the battle, while a tactical draw, severely checked the Russian advance, and along with the recapture of Ruschuk by Ottoman forces a few days later, it looked as though the crossing might be doomed.

The Romanian army crosses the Danube, March of 1877.

However, two events changed that; first, an uprising around Tarnovo forced Suleiman to redirect some of his forces, and second, the Russian reinforcements crossed the Danube in early March. At the battle of Tsarevets on March 7, the Russians were able to beat back the Ottomans within a stone's throw of the bridgehead. The battle was a decisive victory, nearly destroying Suleiman Pasha's army completely, and the Russians could finally advance south; on March 19, Russian troops entered Tarnovo, cheered by the local population.

***

From "The Backyard of Empires: A History of the Balkans, 1850-1916" by Joseph Diefenbaker

Queen's University Press, 2006

Having captured Tarnovo, the Russians held position there for some time. Rather than march further south, they decided to fortify the passes and use the Balkans as a defensive line against the Turks, while constructing actual defensive works along the eastern flank. The offensive focus was shifted west, to deal with Osman's remaining forces and draw troops from the beleaguered Servian army. Marching from Plevna, troops under the Tsesarevich Alexander (later to become Alexander III) [9] captured Gorni Dabnik on March 23, and moved toward Botevgrad. This army, containing Rumanian troops and Bulgarian volunteers in addition to the Russian troops, was to capture Sofia and, eventually, move down the Maritsa to flank the Ottomans before they could strike across the mountains.

Turkish refugees fleeing Tarnovo.

This offensive had the intended effect; the Ottomans withdrew a large portion of the forces invading Servia, and faced east to meet the Russian advance on Sofia. The Serbs were largely able to push the Ottomans outside their borders, and even made a successful offensive into enemy territory, capturing Novi Pazar in early April [10]. The Montenegrins joined the war on the Russian side soon after, and moved quickly, capturing Podgorica and Bar before April's end. What had started as a small-scale war between Servia and the Ottoman Empire had turned into the biggest conflict the area had seen since the Crimean War.

***

[1] The one that ended the Crimean War.

[2] Maronites are Christians, while the Druze are Muslim.

[3] Fun fact: 'bashi-bazouk' is Ottoman Turkish for 'damaged head'.

[4] More or less everything up to this point is OTL; the Russians sent the ultimatum IOTL, and the Porte budged. Here they don't, which has the effect that both sides are a bit less prepared for war, but also that the Ottomans are able to mount a better defence (IOTL their defence minister was assassinated just prior to the declaration of war, and the Russians were able to gain the upper hand very quickly in the face of Ottoman disorganisation).

[5] ITTL, Benjamin Tyler Henry succeeded in taking over New Haven Arms from Oliver Winchester, and what we know as the Winchester rifle, which was a development of the original design by Henry, is still known as the Henry rifle through its production run.

[6] IOTL, the Porte was suffering from the disorganisation brought about by the sudden demise of their defence minister, and they weren't quick enough to man the fortress before the Russians had already captured it; ITTL, the Ottomans are quicker to respond to the crossing.

[7] IOTL, the siege of Plevna lasted six months, as Osman's forces had ensconced themselves within the city; ITTL, with Osman on the run from Nikopol, the city falls fairly quickly to the Russian advance.

[8] IOTL, the Ottomans were checked at the pass by a Russian advance force bolstered by Bulgarian volunteers; in a scene oddly reminiscent of the three hundred Spartans at Thermopylae, a force of 5,000 held six times that number at bay.

[9] Largely the same person as OTL, although a bit more politically apathetic. Nikolai Alexandrovich still dies ITTL.

[10] The Serbs planned to do this IOTL, but the Austrians pressured the Russians into leaving the Sanjak alone, and since Serbia was very much linked to Russia militarily (IOTL and ITTL), they went for Niš instead. Here Austria's influence in the Balkans has been very much curtailed (as per the Treaty of Strassburg), and they're unable to keep the Sanjak from being taken over completely by Serbia.

Gathering Storms

"Si vis pacem, para bellum." ("If you seek peace, prepare for war.")

- Vegetius, De Re Militari

***

From "The Backyard of Empires: A History of the Balkans, 1850-1916" by Joseph Diefenbaker

Queen's University Press, 2006

To look at the causes of the 1870s uprisings, or indeed those of any such events in the region's history, one must make oneself familiar with the Ottoman Empire, and the state of religious discrimination present in it, as it stood at that point. The Treaty of Paris [1], while purportedly guaranteeing the equality of Christians with Muslims, made little change on the ground. Though the jizya had been abolished, and Christians were allowed to serve in the Empire's military, testimonies by Christians against Muslims were still not admissible in court. This holdout from the old legal system made Muslims impervious to legal action, a fact that encouraged discrimination more than anything else.

Lebanon, 1860.

While the Balkans themselves had been relatively quiet for twenty-five years before the uprisings, other areas under Ottoman rule had seen significant unrest. A peasant revolt in Lebanon in 1860 quickly turned into a religious civil war as Druze and Maronite [2] peasants turned on each other, a situation that turned so volatile that the French intervened to protect the Maronites, and eventually forced the appointment of a Christian governor in the region. Later that decade, a large-scale revolt broke out on Crete, and while this uprising was ultimately unsuccessful in its goals of enosis, or unification, of the island with Greece, this was only so because the Porte gave the island home rule in 1869.

The Ottoman economy was greatly weakened by the cost of fighting these constant rebellions, and in addition, the Empire had to take great pains to accommodate the over half a million Circassians expelled from their homes in the Caucasus by Russia, efforts that not only cost a great deal of money, but also led to large-scale social unrest in the Balkan ports through which the Circassians passed.

The single largest issue that led to the rebellions, however, was nationalism. The allegiance of the national to the nation, of the individual to their homeland and to common ideals of, for instance, Servian-ness far outweighed that of the subject to the ruler, especially when that ruler spoke a different language, held a different set of beliefs, lived a different life in a different place and was more liable to send in the army than to listen to his subjects. Rumania had been a de facto independent state since 1848, as had Servia and Montenegro, but there were large areas of land still under Ottoman control in which the populace identified with these nations rather than with the Empire. The Bulgarians and Bosnians, for their part, were even worse off, as they had no lands to call their own whatsoever.

Although most Bosnians were and are Muslim in belief, the region known as Herzegovina, in the south of the country, was populated mainly by Croats, who were Catholic Christians. Catholics were subject to the same discrimination as Orthodox Christians, and the local authorities encouraged unrest by ignoring the discrimination entirely. In March of 1875, the Christian population of Herzegovina broke out in open rebellion against Ottoman authority, an act that opened the flood gates for half a decade of war across the Balkans.

The revolt, which saw significant support from Serb and Montenegrin volunteers, quickly became a running sore, and a year after beginning it still went on, the Ottomans committing more and more troops to quell it. This spurred the Bulgarians into action, and a large-scale uprising broke out in the Bulgarian-inhabited lands in early 1876. The Ottomans, having few regulars to commit to anything except quelling the rebellion in Herzegovina, were forced to send in corps of bashi-bazouks [3], irregulars in the Sultan's service, to quell the Bulgarian uprising. They did so, moving with extreme brutality, and killing Bulgarian revolvers by the thousands.

This famous painting by Makovsky shows a Bulgarian woman being raped by a bashi-bazouk, a distressingly common sight in 1870s Bulgaria.

The brutality of the bashi-bazouks got out quickly, and upon reaching Western Europe, many people there sharply decried the events. The Serbs, for their part, were even more incensed at the slaughter of the rebelling Bulgarians; on June 30, they declared war on the Ottomans. They were supported by Montenegro and by Russian volunteers, and thanks to their broad base of support they were able to fend off the Ottoman army as it invaded. However, in doing so, the Servian army's already meagre strength was severely checked, and they failed to achieve any of their original objectives. Knowing that another attack would likely destroy them, the Serbs asked the Western powers to mediate a truce. The West agreed, and a ceasefire was declared in early September; however, the Turkish terms were not accepted by either the Serbs or the mediators, and so the war went on.

The Ottoman army resumed its offensive as October arrived, and the Servian position became more and more desperate. It was then that the Russian behemoth decided to act, and on October 31, St. Petersburg sent an ultimatum to Constantinople, demanding that they cease the war with Servia. The Russian army was mobilised to back the ultimatum, but the Porte refused to budge. The war had begun [4].

***

From "The Juggernaut of the East: Russia's Army in the 19th Century" by Jérôme Saint-Laurent

Translated into English by Michael Henderson

Schulman Publications, Birmingham, 1999

Immediately after the declaration of war, the Army of the Danube crossed the Prut into Rumania; then-Prince Amadeu had already pledged his support for the Russian side, hoping to gain complete independence from the Ottomans.

The outcome of the war, contrary to what is generally assumed by outside (and especially Russian) observers, was far from guaranteed at the outset; while Russia had a much larger force than the Ottomans (sources estimate that roughly 300,000 troops were within reach of the Balkans at the start of the war, compared to the 120,000 Turkish troops in the region not assigned to garrison duty). However, the Ottomans had better fortifications, naval superiority over the Black Sea and much of the Danube, and most importantly, better equipment. Many Turkish infantrymen were issued the iconic M1874 Henry rifle [5] of American design, and several German Krupp guns were used by the artillery.

The Russian army crossing the Danube.

The major weakness in the Ottoman defence was that they underestimated the Russian strategy; thinking the Russians too lazy to march around the fortifications and strike further up the Danube, they manned their fortifications in the Dobruja fully, leaving only a few troops in the west save for those invading Servia. When the Russian army did cross the river in January of 1877, it did so at Svishtov, thirty miles west of Ruschuk. The Russians had spent much of the preceding months mining the river and gunning down Turkish patrol boats, and after a brief battle, a bridgehead was secured. The Russian army was organised into three forces; one would advance south, toward the Balkan Mountains themselves, while one would watch each flank of the first force's movement.

The Porte responded by sending Osman Nuri Pasha with 18,000 men east from Vidin to the fortress of Nikopol, at the mouth of the Olt, where they arrived on February 2 [6]. The Russian western flank, already on its way to Nikopol, engaged the Turks almost immediately, and although the numbers were close, managed to score a victory, taking the fortress and denying a large stretch of the Danube to Ottoman control. Plevna was captured soon after, following a brief siege [7], and the Russian march south continued.

The Porte had already sent a second army of 30,000, commanded by Suleiman Pasha, to attack the Russians head-on from the south; this army crossed the Balkans at Shipka Pass on February 7 [8], and moved north, reaching the old Bulgarian capital of Tarnovo on the 9th. The Russians were engaged at Vodolei on the 12th; the battle, while a tactical draw, severely checked the Russian advance, and along with the recapture of Ruschuk by Ottoman forces a few days later, it looked as though the crossing might be doomed.

The Romanian army crosses the Danube, March of 1877.

However, two events changed that; first, an uprising around Tarnovo forced Suleiman to redirect some of his forces, and second, the Russian reinforcements crossed the Danube in early March. At the battle of Tsarevets on March 7, the Russians were able to beat back the Ottomans within a stone's throw of the bridgehead. The battle was a decisive victory, nearly destroying Suleiman Pasha's army completely, and the Russians could finally advance south; on March 19, Russian troops entered Tarnovo, cheered by the local population.

***

From "The Backyard of Empires: A History of the Balkans, 1850-1916" by Joseph Diefenbaker

Queen's University Press, 2006

Having captured Tarnovo, the Russians held position there for some time. Rather than march further south, they decided to fortify the passes and use the Balkans as a defensive line against the Turks, while constructing actual defensive works along the eastern flank. The offensive focus was shifted west, to deal with Osman's remaining forces and draw troops from the beleaguered Servian army. Marching from Plevna, troops under the Tsesarevich Alexander (later to become Alexander III) [9] captured Gorni Dabnik on March 23, and moved toward Botevgrad. This army, containing Rumanian troops and Bulgarian volunteers in addition to the Russian troops, was to capture Sofia and, eventually, move down the Maritsa to flank the Ottomans before they could strike across the mountains.

Turkish refugees fleeing Tarnovo.

This offensive had the intended effect; the Ottomans withdrew a large portion of the forces invading Servia, and faced east to meet the Russian advance on Sofia. The Serbs were largely able to push the Ottomans outside their borders, and even made a successful offensive into enemy territory, capturing Novi Pazar in early April [10]. The Montenegrins joined the war on the Russian side soon after, and moved quickly, capturing Podgorica and Bar before April's end. What had started as a small-scale war between Servia and the Ottoman Empire had turned into the biggest conflict the area had seen since the Crimean War.

***

[1] The one that ended the Crimean War.

[2] Maronites are Christians, while the Druze are Muslim.

[3] Fun fact: 'bashi-bazouk' is Ottoman Turkish for 'damaged head'.

[4] More or less everything up to this point is OTL; the Russians sent the ultimatum IOTL, and the Porte budged. Here they don't, which has the effect that both sides are a bit less prepared for war, but also that the Ottomans are able to mount a better defence (IOTL their defence minister was assassinated just prior to the declaration of war, and the Russians were able to gain the upper hand very quickly in the face of Ottoman disorganisation).

[5] ITTL, Benjamin Tyler Henry succeeded in taking over New Haven Arms from Oliver Winchester, and what we know as the Winchester rifle, which was a development of the original design by Henry, is still known as the Henry rifle through its production run.

[6] IOTL, the Porte was suffering from the disorganisation brought about by the sudden demise of their defence minister, and they weren't quick enough to man the fortress before the Russians had already captured it; ITTL, the Ottomans are quicker to respond to the crossing.

[7] IOTL, the siege of Plevna lasted six months, as Osman's forces had ensconced themselves within the city; ITTL, with Osman on the run from Nikopol, the city falls fairly quickly to the Russian advance.

[8] IOTL, the Ottomans were checked at the pass by a Russian advance force bolstered by Bulgarian volunteers; in a scene oddly reminiscent of the three hundred Spartans at Thermopylae, a force of 5,000 held six times that number at bay.

[9] Largely the same person as OTL, although a bit more politically apathetic. Nikolai Alexandrovich still dies ITTL.

[10] The Serbs planned to do this IOTL, but the Austrians pressured the Russians into leaving the Sanjak alone, and since Serbia was very much linked to Russia militarily (IOTL and ITTL), they went for Niš instead. Here Austria's influence in the Balkans has been very much curtailed (as per the Treaty of Strassburg), and they're unable to keep the Sanjak from being taken over completely by Serbia.

So the Ottoman Empire starts the Great War over Serbia, instead of Austria-Hungary. Cool. How are Amero-Russian Relations? I know in OTL the Russians were leaning on the Unions side should Britain and France try anything. While I don't think we would enter the War, would the US sell to both sides?

So the Ottoman Empire starts the Great War over Serbia, instead of Austria-Hungary. Cool. How are Amero-Russian Relations? I know in OTL the Russians were leaning on the Unions side should Britain and France try anything. While I don't think we would enter the War, would the US sell to both sides?

You're reading too much into the last sentence, I'm afraid. TTL's Great War (if it can be called that) doesn't start until much later, and though Russia and the Ottoman Empire are on different sides, the war certainly won't start over Serbia. That's all the clues I'm giving for now; rampant speculation is optional, but welcome.

As for Russo-American relations, they're largely the same as OTL. Russia is one of the closest powers to the US diplomatically, and since there will be no Great Rapproachement ITTL (for a number of reasons), I can't see that changing in the near future.

Ephraim Ben Raphael

Banned

Love the detail and focus, even on things that have always seemed relatively obscure to me.

Love the detail and focus, even on things that have always seemed relatively obscure to me.

Well, I generally only write about things I have some previous knowledge of - you'll notice the conspicuous lack of updates dealing with, say, East Asia in the TL. When I do write about something relatively unknown, I do so slowly, consulting Wikipedia as well as (in some cases) history books along the way. Hence why things tend to come out rather convergent, something I'm growing increasingly self-conscious about; we're twenty-two years away from the PoD, and soon enough I won't be able to base events on real life equivalents. You're likely going to see a dip in the quality of writing when that happens.

Interesting developments, I'm excited to see how the war in the Balkans ends. Also I'm sorry for not being able to vote for you, Ares, but I was busy being fishing.

That's alright. I owe you just for the nomination, and I doubt your vote would've changed anything on the whole.

Ares96 - Very good TL. I'm surprised at myself for not commenting earlier. I'll keep a watch on it from now on, but sometimes I avoid TLs set in the same era as my TLs. I have fear of subconsciously poaching ideas.

Keep up the good work.

Benjamin

Always nice to get new people here. Please do continue to follow.

I think things have changed enough in europe to warrent a map?

Sure have.

I agree fully; however, for three reasons (possibly four) I can't do that at this stage:

1. I haven't found a good basemap of Europe in the period that shows all of the appropriate borders.

2. I'm currently holding out until we reach 1882, at which point the first part/volume/whatever of the TL comes to a close, and at which point I'll post an assortment of maps of the world along with the Around the World and Where Are They Now? segments (for which I'm still accepting requests, BTW).

3. I'm working on a lot of other stuff at the moment (an MoF entry, a new, unrelated AH project, summer job applications, politics, school work, etc.)

(4. I'm kind of lazy when it comes to mapmaking)

I could probably do a quick worlda of Europe at the present, though.

1. I haven't found a good basemap of Europe in the period that shows all of the appropriate borders.

2. I'm currently holding out until we reach 1882, at which point the first part/volume/whatever of the TL comes to a close, and at which point I'll post an assortment of maps of the world along with the Around the World and Where Are They Now? segments (for which I'm still accepting requests, BTW).

3. I'm working on a lot of other stuff at the moment (an MoF entry, a new, unrelated AH project, summer job applications, politics, school work, etc.)

(4. I'm kind of lazy when it comes to mapmaking)

I could probably do a quick worlda of Europe at the present, though.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: