Story of a Party - Chapter XXVII

On the Edge of the Atlantic

"The distinguishing characteristic of small republics is stability: the character of large republics is mutability."

- Simon Bolivar

***

From "A Concise History of Buenos Aires" by Guillermo J. Flores

Translated into English by Stewart Cameron

Pan-American Friendship Committee Press, 1983

"The secession of Buenos Aires from the Confederation can best be understood against the backdrop of the rule of Juan Manuel de Rosas, which lasted from 1835 until 1852, and which, although authoritarian, saw the provinces mostly retaining the rights of self-governance that they had enjoyed since the War of the Federal League. Under Rosas, the country lacked a system of government above the provinces themselves, but as governor of Buenos Aires Province, he was in charge of foreign relations. As such, it was in Rosas' power to intervene in foreign wars, and one such adventure would seal his fate.

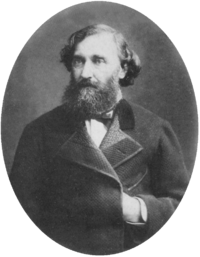

Juan Manuel de Rosas, governor of Buenos Aires and Argentine strongman, in 1840.

In 1842, the former Uruguayan president Manuel Oribe, supported by the Blanco Party and by Rosas, drove off Fructuoso Rivera's [1] Colorados in the Battle of Arroyo Grande; this battle ended with Oribe laying siege to Montevideo, with aid from Rosas. This siege lasted for over nine years, and since Rivera was supported by Brazil and by most European powers, the war severely hindered Argentine trade. In 1845, the British navy blockaded Buenos Aires, and although they withdrew fairly quickly, the blow to relations between the countries further hampered the Argentine economy. The British intervention ended in 1850, by which point the people was fed up with Rosas, and when Justo José de Urquiza, the governor of Entre Rios, declared his province's sovereignty, refusing to delegate diplomatic authority to Buenos Aires, Rosas' rule collapsed like a house of cards.

At this point, Brazil intervened militarily on Urquiza's side, seeking to restore stability and thwart Rosas' ambitions to invade Rio Grande do Sul. The Brazilians, with the aid of Urquiza's forces and the Colorados, drove Rosas away, and Urquiza proceeded to call a constitutional convention to reform the country: despite his revolt against the federalist government, Urquiza was not a unitarian, and indeed wanted further federalisation of the country. He opposed the centralisation of power in Buenos Aires, and wanted the power to be shared more equally among the provinces; this was opposed by most unitarians, but particularly by those from Buenos Aires, who walked out of the convention on September 11, 1853, forming the independent state of Buenos Aires [2]. Manuel Guillermo Pinto was elected governor of the newly sovereign state, and Bartolomé Mitre was placed in charge of the provincial militia.

The newly independent city of Buenos Aires celebrates its first constitution, 1854.

The year after, a constitution was signed, and tensions continued to brew between the Confederation and the rogue province. Budget deficits prompted the Confederation to construct an inland port at Rosario, and subsequently to sign an agreement with Rivera (who regained control over Uruguay after the siege was lifted and Argentina collapsed). These moves only slightly decreased Buenos Aires' importance to the region, and the province steadfastly maintained its independence.

In October of 1858, Nazario Benavídez, governor of San Juan Province and prominent federalist, was murdered by his own guards. In the then-present political climate, it was logical to assume that the murder was carried out at the request of the local unitarian faction, and when faced with the sudden and dramatic appearance of a legitimate casus belli, Urquiza did the only logical thing and declared war on Buenos Aires [3]. The battle broke out at Pergamino, near the border of Buenos Aires Province, and although outnumbered, Mitre was victorious in battle. The Confederate force retreated to Rosario, where Urquiza reluctantly agreed to a truce with Mitre and the separatists. Urquiza was forced to recognise Buenos Aires' independence, with the borders of the province as laid down previously. In exchange, Argentine trade was to be given a privileged status in the port, and the freedom of navigation along the Paraná, which had originally been laid down after the Cisplatine War, was allowed to continue.

After the peace, Buenos Aires renamed itself the Republic of the Rio de la Plata, although it continued to be referred to as Buenos Aires by everyone except the government [4], and its governor Valentín Alsina was proclaimed the nation's first president."

***

From "The Inland Mouse that Roared: A History of Paraguay under the Lopez Family, 1840-1867" by Chesney Keaton

Schulman Publishing, London, 1968

"In 1864, Uruguay was yet again caught in the storm of civil war [5]. Its Blanco president Atanasio Aguirre had refused Brazilian demands to pay damages for border skirmishes against Brazilian nationals, and Brazil responded by closing off diplomatic relations and backing a revolt led by the Colorado Venancio Flores. The revolt received tacit backing from Buenos Aires, but the Brazilians intervened militarily, capturing Montevideo for Flores in October.

Lopez, who had been a supporter of the Aguirre regime, declared the Brazilian intervention a threat to regional stability, but did not immediately declare war; instead he chose to try to incite a declaration of war from Brazil by capturing a Brazilian riverboat heading for Mato Grosso. When these attempts failed, he declared war on Brazil. The Great Paraguayan War had begun…

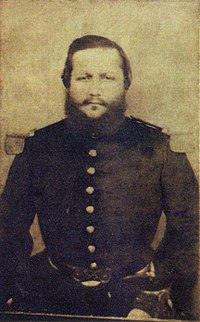

Paraguayan president Francisco Solano Lopez.

At the onset of the war, the Paraguayan army was significantly larger than those of its enemies, numbering nearly 70,000 men. However, although impressive on paper, there were many flaws in this force; the infantrymen were forced to use obsolete smoothbore muskets and carbines that were slow and complicated to load and fire, the artillery was similarly outdated, no one had any real combat experience to speak of, and there was little to no command structure above the platoon level, as Lopez was expected to make all decisions. In addition, logistics were severely deficient, and hospital care was completely unheard of. In contrast, the Brazilian army was smaller, numbering about 16,000 men, but many of its officers were battle-hardened after the wars against Rosas and Aguirre, and its equipment and logistics, although deficient, were still superior. In summary, the Paraguayan army was a massive paper tiger, but the initial operations showed little of this.

Lopez' first move was to move armies north, into Mato Grosso, seeking to divert Brazilian forces away from his main objectives in Rio Grande do Sul and Uruguay. To this end, in March of 1865 Lopez asked Manuel Ignacio Lagraña, governor of Corrientes, for permission to march an army of 25,000 across the province [6]. Lagraña was pressured, due to the small size of his province and the difficulty of defending it properly, into accepting the offer. President Jordán's [7] government was ambivalent to this move, leaning on opposition, but hesitated to move against the Paraguayans because of a desire to avoid another costly war. In contrast, Bartolomé Mitre, who was president of Buenos Aires by this point, vocally chastised the Paraguayans for their "act of aggression against the Uruguayan people" which in his view "threaten[ed] to destabilise the entire Platinean region". On April 5, Mitre declared war on Paraguay, joining with Brazil and Uruguay, and readied the army of Buenos Aires to cross the Rio de la Plata.

Two Brazilian soldiers posing for a photograph with their gear, 1865.

Meanwhile, Lopez had appointed General Wenceslao Robles to command the expeditionary force, which crossed the Paraná into Argentine land on March 21. São Borja was captured on June 17; Uruguaiana fell in early August. The Brazilians failed to intercept these moves because of being tied down in Mato Grosso; in this sense, Lopez's gambit had paid off. However, he had underestimated Flores and Mitre's forces."

***

From "A Concise History of Buenos Aires" by Guillermo J. Flores

Translated into English by Stewart Cameron

Pan-American Friendship Committee Press, 1983

"Mitre arrived in Colonia del Sacramento on July 2; his army joined with that of Flores two weeks after in Trinidad, at which point the combined army marched west to the banks of the Uruguay, and then north along the river to intercept the Paraguayans.

Before Mitre could arrive in Uruguaiana, the Brazilians had raised a ragtag army of hastily recruited gauchos-turned-soldiers and National Guard officers, and marched on São Borja. The city, only lightly garrisoned by the overextended Paraguayans, fell on September 16. The logistics of the Paraguayan army, which were already severely strained, only grew worse as Robles was trapped in Uruguaiana.

Paraguayan fortifications at Uruguaiana.

In early October, Mitre approached Uruguaiana, and after defeating Robles' starved and demoralised army in the field, laid siege to the city. He was soon joined by the Brazilians, and the city fell by the All Saints…"

***

From "The Inland Mouse that Roared: A History of Paraguay under the Lopez Family, 1840-1867" by Chesney Keaton

Schulman Publishing, London, 1968

"The trapping of Robles in Uruguay proved disastrous for Lopez, as the main Paraguayan field army had been completely broken. In addition to attrition suffered because of the logistical problems (before and after São Borja's recapture), the army had been decimated by Mitre's frontal assault and the subsequent siege. What remained of the army was now taken prisoner by the Brazilians. This was doubly disastrous because not only had the expeditionary force made up about a third of the Paraguayan army, they were also given the best equipment and the most capable commanders. What remained of the Paraguayan army was a mob of unorganised militiamen with outdated arms, inept command, atrocious logistics and no hospital service whatsoever.

A company of volunteers from the Brazilian province of Ceará, 1866.

Lopez was not blind to the danger of the situation, and pulled back the bulk of his forces from Mato Grosso. When in September of 1866 the Brazilian army crossed the border, taking Ciudad del Este, he decided to ask the Brazilians to come to the table, asking Urquiza's aid in mediating a peace treaty. The Brazilians agreed, and the sides of the war met in Corrientes to negotiate peace.

Brazil demanded the cession of a large swathe of territory in the northeast of the country. In addition, the Uruguayans demanded Lopez stop interfering in their internal politics, and disarm much of their brown-water fleet to ensure the peaceful resumption of commerce in the Paraná and Uruguay river systems. These terms were reluctantly agreed to by Lopez, but when Buenos Aires demanded that Lopez step down, the Paraguayans walked out of the conference, and the war was resumed.

The Brazilians continued to move west, capturing Minga Guazú a week after the conference's end, while Mitre's army moved south, taking Encarnación in mid-December. When the Brazilians marched on Villarrica, halfway to Asunción, Lopez marched what remained of his army into the field to check the Brazilian advance.

Lopez personally led his army against that of the Brazilian commander, the Duke of Caxias, at Sapucai. The resulting battle, the biggest in the war, pitted 17,000 Paraguayans against only 9,000 Brazilians, but the Brazilians were far superior in nearly every aspect. Sapucai ended a bloody rout, as the Brazilians marched on toward Asunción, and Lopez himself was taken prisoner.

The Battle of Sapucai, Brazilian artillery.

What remained of the Paraguayan government, which before the war had largely consisted of Lopez himself, offered to surrender in March; the Brazilians accepted, and entered the capital two weeks later. The resulting peace treaty saw Lopez formally removed from office, along with the terms previously demanded, and a large war indemnity to be paid to the victorious nations. The Brazilian army also occupied Paraguay east of the Paraguay River until 1870, at which point the nation started functioning again.

The war had harmed Paraguay tremendously; the state coffers were completely empty, and around 250,000 people had died - over a fifth of the nation's population [8]. The battered nation had difficulty rebuilding itself after the devastation of war, and in 1873 it joined Argentina by request, becoming divided into the Province of Paraguay east of the river, and the Chaco Federal Territory, which included the Argentine lands north of to the west."

***

[1] In addition to having the backing of Brazil, Britain and France, Rivera had what is quite possibly the very silliest name in Latin American history (and trust me, there have been some rather silly names). And he

still lost.

[2] It seems that date is fairly ominous in history.

[3] Everything up to this point is OTL.

[4] And sometimes even by the government; Argentina has a long and rich tradition of not making up its mind about its official name, and continues to have at least three official names according to its constitution (the Argentine Republic, the Argentine Confederation and the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata), and this tradition would likely be carried on by the independent Buenos Aires.

[5] It strikes me as ironic that the nation often described as the most stable democracy in Latin America was at the centre of nearly every major conflict in the area.

[6] IOTL, Lopez asked Mitre (who was then President of Argentina) this, and was firmly rebuffed; ITTL, due to Argentina's more confederal nature, he asks the provincial governor instead.

[7]

Ricardo López Jordán was an Argentine federalist, and one of Urquiza's most prominent critics. Jordán opposed

porteño dominance, and agitated against the Paraguayan War of OTL on the grounds that it solidified the unitary republic Mitre had created (obviously not the case ITTL), and that the Brazilians were a greater threat than Paraguay.

[8] TTL's Paraguayan War was still much easier on Paraguay than the OTL one, which lasted nearly seven years and killed over half a million people.