Can't wait for ChileOh boy - time for the post-glacial fractal that is Canada. Good luck with that.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The R-QBAM main thread

- Thread starter Tanystropheus42

- Start date

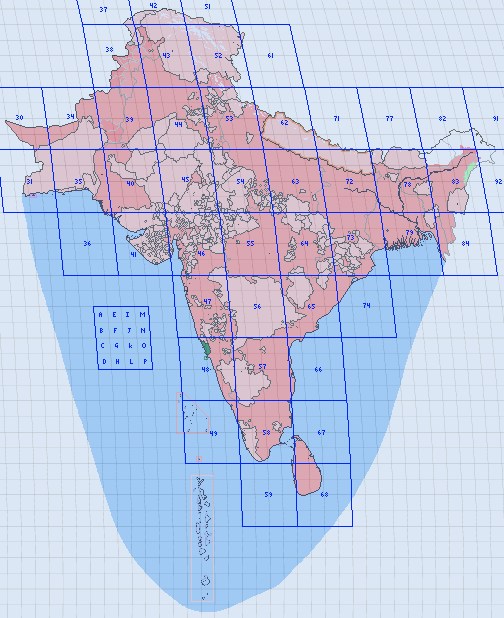

And it's done!

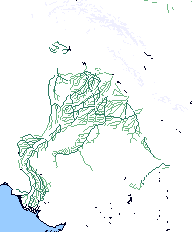

Well, hi guys... Yeah I know another hiatus in my part, but hey the Indian Subcontinent is finished, at least on the physical side of things (the canals will happen soon, I hope)... Not gonna lie, the Brahmaputra gived me headcaches, but it is there now.

So taging @Tanystropheus42 (that btw congrats on the last updates) to show some lakes I did add, specially on the Hiamlayas just to make both Indus and Bramahputra basins complet, what is not in red are wetlands stuff so yeah

So yeah, if anything don't mess with my schedule again, next week I should have more stuff to show... Hopefully the canals if I peferm an miracle? So, see ya guys

Ok, hi again guys (and @Tanystropheus42 for reasons), here's some really minor updates + an extra thing:

- I did mess up a little bit the eastern Bangladesh minor rivers between Surma and Kalni rivers, I corrected it now; also I completely missed the HUGE wetland area there, which also host a permanent substantial lake/lakes area of Tanguar Haor near Meghalaya border, (although the Hukkanachhadi Beel and Nollah Haor could be permanent lakes too, but I'm not sure on these so they are part of the greater wetland), I put a single coast pixel there to show the Tanguar Haor, still little dubious, kinda;

- I also did add the wetland of the Atrai River in Bangladesh and also did add the Kosi River wetland in Bihar (there was massives floods there so it should be shown);

- Speaking of massive floods, I still didn't finish it but I'm also mapping the area flooded by 2022 Pakistan floods, since well it is a wetland are, I'm not so sure how to portray it (probably I'll need to get canals done for that);

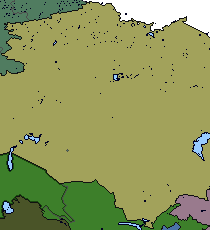

- And updates on... Kazakhstan? Yep, two things there, one is that in it's nothern border with Omsk Oblast, in the part where it almost looks that there's a Russian enclave (which is not), it got painted as a water...

- The other update is more relevant, because this time there's an actual (pero no mucho?) Russian enclave inside Kazakhstan, the city of Baikonur is often forgotten that is leased and administered by Russia since 1991 til 2050 because of the Cosmodrome, going by my river map it should be around here, not sure on how to represent since it's not Russian land exaclty, but it's there now;

Now why exactly did I notice the things on Kazakhstan? Well I was looking for another source for administrative divisions and I stumble on MapChart site, it's a online map maker site that actually has an updated adm. divisions to 2023? It has the last changes in Indonesia's Papua rigions from last year for example, so it can be helpful despite not high definition and traceble...

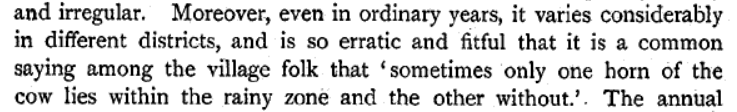

However I took the opportunity and made this map based on that Wikipedia's list I comented on quite ago on federal, unitary and regional adm. divisions types, not perfect but that helps a bit, and yeah my comments on both Sudans federalism and the Iraqi federal entities being the governorates not Kurdistan Region and the rest of Iraq (the KRI still a thing but it's composed of governorates too)

- I did mess up a little bit the eastern Bangladesh minor rivers between Surma and Kalni rivers, I corrected it now; also I completely missed the HUGE wetland area there, which also host a permanent substantial lake/lakes area of Tanguar Haor near Meghalaya border, (although the Hukkanachhadi Beel and Nollah Haor could be permanent lakes too, but I'm not sure on these so they are part of the greater wetland), I put a single coast pixel there to show the Tanguar Haor, still little dubious, kinda;

- I also did add the wetland of the Atrai River in Bangladesh and also did add the Kosi River wetland in Bihar (there was massives floods there so it should be shown);

- Speaking of massive floods, I still didn't finish it but I'm also mapping the area flooded by 2022 Pakistan floods, since well it is a wetland are, I'm not so sure how to portray it (probably I'll need to get canals done for that);

- And updates on... Kazakhstan? Yep, two things there, one is that in it's nothern border with Omsk Oblast, in the part where it almost looks that there's a Russian enclave (which is not), it got painted as a water...

- The other update is more relevant, because this time there's an actual (pero no mucho?) Russian enclave inside Kazakhstan, the city of Baikonur is often forgotten that is leased and administered by Russia since 1991 til 2050 because of the Cosmodrome, going by my river map it should be around here, not sure on how to represent since it's not Russian land exaclty, but it's there now;

Now why exactly did I notice the things on Kazakhstan? Well I was looking for another source for administrative divisions and I stumble on MapChart site, it's a online map maker site that actually has an updated adm. divisions to 2023? It has the last changes in Indonesia's Papua rigions from last year for example, so it can be helpful despite not high definition and traceble...

However I took the opportunity and made this map based on that Wikipedia's list I comented on quite ago on federal, unitary and regional adm. divisions types, not perfect but that helps a bit, and yeah my comments on both Sudans federalism and the Iraqi federal entities being the governorates not Kurdistan Region and the rest of Iraq (the KRI still a thing but it's composed of governorates too)

Hi again, once more other update, hmm... Not gonna lie that this is driving me a bit crazzy but yeah, I tried making some sense on the Indus canal system + the canals on Indian Punjab, Harayana and Rajasthan... I pretty confident that the Pakistani ones and the Indira Gandhi canal are right, the other Indian ones are, let's say complicated...

Well here they are:

Of course there is more canals on India, but I think is better to search more in that

Well here they are:

Of course there is more canals on India, but I think is better to search more in that

I've been meaning to write up some long-overdue replies for some time now, but never quite got around to doing it. Eh, better late than never I suppose.

Well done on finishing the rivers of India. I'll go over the lakes you added in Tibet when I get to Tibet myself (probably at some point next year, once the Americas are done), but there shouldn't be any major problems when that happens.

I fear I'm about to give you quite a bit more work to do, as in a minute or two I'll be posting the next major patch, adding Quebec and the Labrador coast. Don't be surprised if it ends up taking a very long time to add the rivers - I've been diligently chipping away at it for nearly a month, though hopefully it shouldn't be as bad with the lakes and coastlines to work from.

One minor point - I may end up tweaking your rivers map in one or two places to get some of the raw geography to match up with the Raj patch, however that is a job I'll get to when I set about finishing the Raj over the next few weeks, so it won't be done immediately. A few minor corrections aside, I'll reiterate what I said above, congrats on a difficult job done well, I'm sorry for dumping Quebec on you out of the blue.

Y'know, I've had a few bad experiences trying to get stuff published; every now and again while at uni, I'd crank out a piece of coursework I was told was publication-worthy, only for a variety of things I won't be getting into here to get in the way and stop that happening, so I'd be a little wary of trying again.

Hey, it's not a complete waste; aside from R-QBAM patch itself, I've tried very hard to both highlight all the difficult decisions and iffy judgements I made compiling the Raj patch, as well as lay out the reasons I made them, and cite my sources throughout (both textual and cartographic) which should provide a good framework if anyone else wants to do another deep-dive. All the maps are right here if anyone possessing the GIS abilities I profoundly lack wants to have a stab at making a new improved dataset.

Firstly, it's great to see everything collated in one place, especially for someone as generally disorganised as myself, so thanks for doing that.

However I particularly like the Koppen maps, as they illustrate why this project has the potential to be so useful. Trying to warp such a map to fit the old QBAM would be a herculean task, considering the inconsistent nature and unknown projection of the latter map. For the R-QBAM however, it's as simple as finding the right dataset and reprojecting it, which is so much easier.

That's from the Directory isn't it?

It's both intriguing and infuriating as a source. On the one hand, it records so much local detail and trivia that has probably never been preserved elsewhere, and is peppered with little tit-bits and anecdotes like the one you highlighted. However it is also vague, imprecise and wildly inconsistent in places, meaning any conclusions drawn from it are by necessity highly uncertain. It's maddening.

My current working hypothesis is that the Nimsod hoax was a case of some incredibly minor Indian noble trying to falsify the record and make their ancestors look more important than they really were. Hence the shoehorning of the family name and purported state they ruled into all kinds of tangentially related articles to try and make the lie look more legitimate.

Based on that I'd say it's fairly likely that the two articles you highlight are probably dodgy as well, however I'd hold off on deleting them as there's always the chance the family did possess some territory at some earlier point, and that the embellishments and falsehoods only applied to later history. I personally suspect that this is not the case based on how much later history was invented or falsified, however as my researches have primarily focused on the petty states during the era of British rule, I wouldn't be confident completely dismissing the purported earlier history with which I am less familiar. I'd leave it be for now, though with a massive question mark over its validity.

I guess so? I would be unlikely to produce a historical map that old myself, as I'm such a perfectionist that I prefer producing historical maps from times when the sources are plentiful and precise enough that I can be pretty damn sure about the true extent and nature of the entities in question. I tend to stick to the 19th century or later for this reason, but if sources are good enough and people want it then I'll happily whip up historical geography patches as necessary.

Wait till you see the next patch.

Honestly, I'm not that worried about Chile; the difficult bit is about the same length and complexity as the Norwegian coastline, and that only took me a week and a half to finish back in May last year. Canada is sooooo much worse.

Thanks for pointing out that mis-coloured pixel in Kazakhstan (it has since been fixed). I try my best to make sure little mistakes like that don't creep in too often, but we all slip up from time to time.

I was really uncertain about how or even whether to show the Baikonur cosmodrome when I originally added Kazakhstan, though I eventually decided to omit it, in no small part because I couldn't for the life of me find consistent borders for the claimed leased territory. Plenty of maps and mapping services don't show it at all, while among those that do I've seen some wildly divergent portrayals of how big the leased area is, as that lease apparently covers quite a lot more than just the immediate area around the cosmodrome; I've seen maps giving Russia a massive random circle of the Kazakh steppes for example.

Adding first level admin divisions to the federal states that I've missed is a job I'm saving for later, when the main map is done and I can focus my efforts on just adding administrative levels to those countries missing them. It will be done, just don't expect it done soon.

As I said above, the next patch is coming soon.

And it's done!

Well, hi guys... Yeah I know another hiatus in my part, but hey the Indian Subcontinent is finished, at least on the physical side of things (the canals will happen soon, I hope)... Not gonna lie, the Brahmaputra gived me headcaches, but it is there now.

So taging @Tanystropheus42 (that btw congrats on the last updates) to show some lakes I did add, specially on the Hiamlayas just to make both Indus and Bramahputra basins complet, what is not in red are wetlands stuff so yeah

Well done on finishing the rivers of India. I'll go over the lakes you added in Tibet when I get to Tibet myself (probably at some point next year, once the Americas are done), but there shouldn't be any major problems when that happens.

I fear I'm about to give you quite a bit more work to do, as in a minute or two I'll be posting the next major patch, adding Quebec and the Labrador coast. Don't be surprised if it ends up taking a very long time to add the rivers - I've been diligently chipping away at it for nearly a month, though hopefully it shouldn't be as bad with the lakes and coastlines to work from.

One minor point - I may end up tweaking your rivers map in one or two places to get some of the raw geography to match up with the Raj patch, however that is a job I'll get to when I set about finishing the Raj over the next few weeks, so it won't be done immediately. A few minor corrections aside, I'll reiterate what I said above, congrats on a difficult job done well, I'm sorry for dumping Quebec on you out of the blue.

At this point I genuinely think you could compile all of this and look at submitting it to an academic journal.

Just add some conclusions at the end about the validity/usefulness of certain sources and use the 'I got an erroneous article deleted from Wikipedia' bit as a hook.

Y'know, I've had a few bad experiences trying to get stuff published; every now and again while at uni, I'd crank out a piece of coursework I was told was publication-worthy, only for a variety of things I won't be getting into here to get in the way and stop that happening, so I'd be a little wary of trying again.

I just wish all of this research didn't get lost on a few pixels, this could very easily be a big and detailed map or maybe even a GIS source.

Hey, it's not a complete waste; aside from R-QBAM patch itself, I've tried very hard to both highlight all the difficult decisions and iffy judgements I made compiling the Raj patch, as well as lay out the reasons I made them, and cite my sources throughout (both textual and cartographic) which should provide a good framework if anyone else wants to do another deep-dive. All the maps are right here if anyone possessing the GIS abilities I profoundly lack wants to have a stab at making a new improved dataset.

I present you the R-QBAM Repository !

R-QBAM Köppen climate maps:

Firstly, it's great to see everything collated in one place, especially for someone as generally disorganised as myself, so thanks for doing that.

However I particularly like the Koppen maps, as they illustrate why this project has the potential to be so useful. Trying to warp such a map to fit the old QBAM would be a herculean task, considering the inconsistent nature and unknown projection of the latter map. For the R-QBAM however, it's as simple as finding the right dataset and reprojecting it, which is so much easier.

Incredible work, I especially liked this hidden gem:

I think everywhere on earth has some version of this saying lol. It seems we all want to one-up each other when it comes to how extreme our local weather is.

That's from the Directory isn't it?

It's both intriguing and infuriating as a source. On the one hand, it records so much local detail and trivia that has probably never been preserved elsewhere, and is peppered with little tit-bits and anecdotes like the one you highlighted. However it is also vague, imprecise and wildly inconsistent in places, meaning any conclusions drawn from it are by necessity highly uncertain. It's maddening.

Well, there's as good a reason as any to revive my long-dormant Wikipedia account. Thankfully the successful article for deletion provides a pretty easy shorthand reference for the edit rather than having to justify it.

I believe there are now only 2 pages where a reference to some sort of Nimsod State-

It appears in a list of Talukas of Subha Prant Khatao in the article on Lalgun - which I'd appreciate clarification on whether this is correct, incorrect or one of these 'oh god we've got to go through the process of sourcing why that's incorrect' edits. Though that doesn't list a Raja of Nimsod anyway.

There's also an article on the hillfort at Bhushangad which I'm looking at atm and... well just removing the Nimsod Rajas is easy but the whole article seems to be full of suspect information. Which is impressive when I think you've written more words on summarising the difficulties of enumerating the total number of Princely States just there than are in the article.

There's also a fair number of references still to Gharge-Desai Deshmukh which refer to an article created by the guy who created the one on Nimsod State, but I'm honestly not sure if that isn't the 'one actual bit of history' the rest was built on.

My current working hypothesis is that the Nimsod hoax was a case of some incredibly minor Indian noble trying to falsify the record and make their ancestors look more important than they really were. Hence the shoehorning of the family name and purported state they ruled into all kinds of tangentially related articles to try and make the lie look more legitimate.

Based on that I'd say it's fairly likely that the two articles you highlight are probably dodgy as well, however I'd hold off on deleting them as there's always the chance the family did possess some territory at some earlier point, and that the embellishments and falsehoods only applied to later history. I personally suspect that this is not the case based on how much later history was invented or falsified, however as my researches have primarily focused on the petty states during the era of British rule, I wouldn't be confident completely dismissing the purported earlier history with which I am less familiar. I'd leave it be for now, though with a massive question mark over its validity.

When you get to the Tarim Basin, will you do Patches for the different levels of the Lop Nur Lake historically?.

I guess so? I would be unlikely to produce a historical map that old myself, as I'm such a perfectionist that I prefer producing historical maps from times when the sources are plentiful and precise enough that I can be pretty damn sure about the true extent and nature of the entities in question. I tend to stick to the 19th century or later for this reason, but if sources are good enough and people want it then I'll happily whip up historical geography patches as necessary.

Oh boy - time for the post-glacial fractal that is Canada. Good luck with that.

Wait till you see the next patch.

Can't wait for Chile

Honestly, I'm not that worried about Chile; the difficult bit is about the same length and complexity as the Norwegian coastline, and that only took me a week and a half to finish back in May last year. Canada is sooooo much worse.

- And updates on... Kazakhstan? Yep, two things there, one is that in it's nothern border with Omsk Oblast, in the part where it almost looks that there's a Russian enclave (which is not), it got painted as a water...

- The other update is more relevant, because this time there's an actual (pero no mucho?) Russian enclave inside Kazakhstan, the city of Baikonur is often forgotten that is leased and administered by Russia since 1991 til 2050 because of the Cosmodrome, going by my river map it should be around here, not sure on how to represent since it's not Russian land exaclty, but it's there now;

Thanks for pointing out that mis-coloured pixel in Kazakhstan (it has since been fixed). I try my best to make sure little mistakes like that don't creep in too often, but we all slip up from time to time.

I was really uncertain about how or even whether to show the Baikonur cosmodrome when I originally added Kazakhstan, though I eventually decided to omit it, in no small part because I couldn't for the life of me find consistent borders for the claimed leased territory. Plenty of maps and mapping services don't show it at all, while among those that do I've seen some wildly divergent portrayals of how big the leased area is, as that lease apparently covers quite a lot more than just the immediate area around the cosmodrome; I've seen maps giving Russia a massive random circle of the Kazakh steppes for example.

Adding first level admin divisions to the federal states that I've missed is a job I'm saving for later, when the main map is done and I can focus my efforts on just adding administrative levels to those countries missing them. It will be done, just don't expect it done soon.

As I said above, the next patch is coming soon.

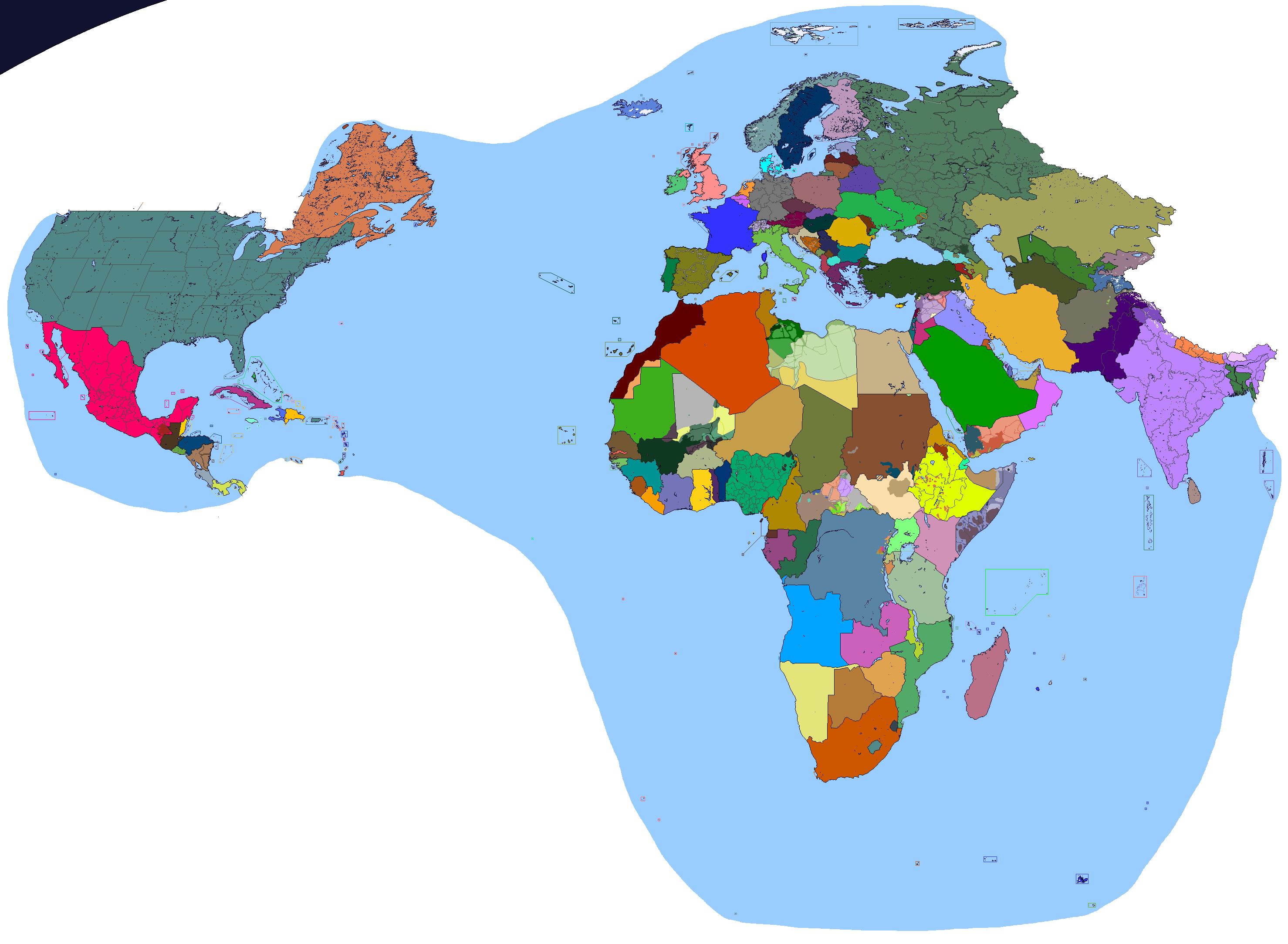

I know I said in the last patch that I'd be spending a fortnight or so trying to finish the Raj, but that isn't what ended up happening. For a variety of reasons, I really wanted to get some more work done expanding the basemap, so much so that I didn't even mind that the next area up on the schedule was Quebec. It won't be too bad, I naively thought to myself, perhaps just another Scandinavia, which was difficult but doable. This was a bit larger, but I didn't expect it to take longer than a fortnight or so.

Then I got started, and quickly realised just how daunting the task I had set myself was. After a week I was beginning to regret the decision, largely because dealing with the fractal hell that are the thousands of Canadian lakes quickly became a real slog, but by that point I was far enough in that I wanted to finish it, no matter how long that took. What I initially expected to be a two-week job at maximum instead ended up taking the better part of a month, largely thanks to the hideous lakes of Quebec (to give you an idea, large chunks of Quebec look like this) and the many fjords of the Labrador coast. It was like combining the Norwegian coasts with the lakes of Finland, except here covering an area roughly five times as large.

I've really, really, really come to hate the Ice ages over the last three weeks.

So yeah, that's why today's patch took rather longer to finish than originally advertised; Canada is hellish, and there's even more left to do (yaaaay /s).

I also did a few other things, because by the end of the slog I really wanted to break up the monotony of endless fractal lakes with something a little different. I upgraded modern India to account for changes made while compiling the Raj patch (more on that below), changed up the colour scheme a little, merged the Americas with Afro-Eurasia and bashed out a couple of simple AH maps that may crop up in that map thread at some point over the next week or so if I can find the time to give them a basic write-up.

The biggest of the above-mentioned changes was India. I've said it a couple of times, but one of the main reasons I ploughed ahead with historical patches was that it gave me a chance to go over everything again. While putting together the historical geographic patch I ended up tweaking some of the existing Indian lakes, adding some and removing others, while also making a few tweaks to the coastline of southern India, particularly in Karnataka. These have been updated in this latest version of the map. Considering a lot of Raj-era borders correspond to modern first-level borders in both India and Pakistan, I also made a lot of tweaks where a more detailed look at the area in question found the original R-QBAM borders wanting. These have also been patched, bringing the modern map in-line with the historical patches as produced so far.

Random bit of trivia, but while surveying the lakes of Quebec I noticed something; by my count, there are no less than six meteorite impact craters visible on the R-QBAM as lakes in Quebec and Labrador; La Moinerie, Mistastin, Couture, Clearwater East, Clearwater West and Manicouagan. In the rest of the world finished so far, I can only think of three others off the top of my head similarly easily visible; the Siljan ring in Sweden, the lake at the bottom of the eponymous Karakul crater in Tajikistan and lake Bosumtwi in Ghana.

Earth has a fair number of impact craters, but most aren't that visible on the surface. Most have either been buried under later sediment, partially eroded away, deformed by later tectonic processes or some combination of the above. Quebec however is slap bang in the middle of the Laurentian Shield, an ancient expanse of continental rock that has been stable for billions of years, making it a big target that has existed for aeons to soak up any meteors headed its way. The Ice ages then came along and scoured away most later overlying sediment cover, revealing the impact scars in the bedrock beneath.

It's funny the odd things you notice spending weeks looking at endless fractal lakes.

Next up I'll be finishing the Raj patch (for real this time), and while I'm pretty confident that this will only take a fortnight or so, it may take longer, so don't be surprised if there's another long wait.

The other job that needs doing came about in large part thanks to having to slog through the lakes of Quebec; another lakes purge for the US, Mexico and Central America. Quite simply, northern Quebec is horrible. There are lakes everywhere, and so out of sheer necessity I was forced to be very selective when considering which bodies of water were big enough to be shown. On the other hand, when I originally did the rest of North America and the Caribbean, my standards for how big a lake has to be to be shown were rather lower, so I feel another purge of the smallest lakes is necessary to bring the two regions more in-line with each other.

Once both of those are done, the next patch will be the rest of Ontario, followed by Colombia and Venezuela.

Patch 93 - Oh, Canada 2 (Quebec and Labrador);

- Added Quebec

- Added Labrador, completing the province of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Added a few Nunavut islands close enough to Quebec that I had to add them out of necessity.

- Mildly patched the rest of Canada so-far completed.

- Merged the American frame-of-reference with the Afro-Eurasian frame-of-reference to produce one unified map.

- Related to the above, added the first bit of Brazil; the tiny Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, a cluster of isolated islands in the middle of the Atlantic under Brazil's sovereignty.

- Implemented extensive patches in the Indian subcontinent to account for changes made while compiling the 1914 Raj patch. These include some coastal tweaks, a further overhaul of Indian lakes, and extensive patches to inter-state borders in both India and Pakistan to bring the modern administrative borders in-line with their antecedent Raj-era borders.

- Tweaked the colour scheme in places to fix some long-standing issues I have had with certain colours. Germany and India received more muted variants of their previous colours, while Kuwait, Bahrain and Belize gained bespoke new colours.

Then I got started, and quickly realised just how daunting the task I had set myself was. After a week I was beginning to regret the decision, largely because dealing with the fractal hell that are the thousands of Canadian lakes quickly became a real slog, but by that point I was far enough in that I wanted to finish it, no matter how long that took. What I initially expected to be a two-week job at maximum instead ended up taking the better part of a month, largely thanks to the hideous lakes of Quebec (to give you an idea, large chunks of Quebec look like this) and the many fjords of the Labrador coast. It was like combining the Norwegian coasts with the lakes of Finland, except here covering an area roughly five times as large.

I've really, really, really come to hate the Ice ages over the last three weeks.

So yeah, that's why today's patch took rather longer to finish than originally advertised; Canada is hellish, and there's even more left to do (yaaaay /s).

I also did a few other things, because by the end of the slog I really wanted to break up the monotony of endless fractal lakes with something a little different. I upgraded modern India to account for changes made while compiling the Raj patch (more on that below), changed up the colour scheme a little, merged the Americas with Afro-Eurasia and bashed out a couple of simple AH maps that may crop up in that map thread at some point over the next week or so if I can find the time to give them a basic write-up.

The biggest of the above-mentioned changes was India. I've said it a couple of times, but one of the main reasons I ploughed ahead with historical patches was that it gave me a chance to go over everything again. While putting together the historical geographic patch I ended up tweaking some of the existing Indian lakes, adding some and removing others, while also making a few tweaks to the coastline of southern India, particularly in Karnataka. These have been updated in this latest version of the map. Considering a lot of Raj-era borders correspond to modern first-level borders in both India and Pakistan, I also made a lot of tweaks where a more detailed look at the area in question found the original R-QBAM borders wanting. These have also been patched, bringing the modern map in-line with the historical patches as produced so far.

Random bit of trivia, but while surveying the lakes of Quebec I noticed something; by my count, there are no less than six meteorite impact craters visible on the R-QBAM as lakes in Quebec and Labrador; La Moinerie, Mistastin, Couture, Clearwater East, Clearwater West and Manicouagan. In the rest of the world finished so far, I can only think of three others off the top of my head similarly easily visible; the Siljan ring in Sweden, the lake at the bottom of the eponymous Karakul crater in Tajikistan and lake Bosumtwi in Ghana.

Earth has a fair number of impact craters, but most aren't that visible on the surface. Most have either been buried under later sediment, partially eroded away, deformed by later tectonic processes or some combination of the above. Quebec however is slap bang in the middle of the Laurentian Shield, an ancient expanse of continental rock that has been stable for billions of years, making it a big target that has existed for aeons to soak up any meteors headed its way. The Ice ages then came along and scoured away most later overlying sediment cover, revealing the impact scars in the bedrock beneath.

It's funny the odd things you notice spending weeks looking at endless fractal lakes.

Next up I'll be finishing the Raj patch (for real this time), and while I'm pretty confident that this will only take a fortnight or so, it may take longer, so don't be surprised if there's another long wait.

The other job that needs doing came about in large part thanks to having to slog through the lakes of Quebec; another lakes purge for the US, Mexico and Central America. Quite simply, northern Quebec is horrible. There are lakes everywhere, and so out of sheer necessity I was forced to be very selective when considering which bodies of water were big enough to be shown. On the other hand, when I originally did the rest of North America and the Caribbean, my standards for how big a lake has to be to be shown were rather lower, so I feel another purge of the smallest lakes is necessary to bring the two regions more in-line with each other.

Once both of those are done, the next patch will be the rest of Ontario, followed by Colombia and Venezuela.

Patch 93 - Oh, Canada 2 (Quebec and Labrador);

- Added Quebec

- Added Labrador, completing the province of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Added a few Nunavut islands close enough to Quebec that I had to add them out of necessity.

- Mildly patched the rest of Canada so-far completed.

- Merged the American frame-of-reference with the Afro-Eurasian frame-of-reference to produce one unified map.

- Related to the above, added the first bit of Brazil; the tiny Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, a cluster of isolated islands in the middle of the Atlantic under Brazil's sovereignty.

- Implemented extensive patches in the Indian subcontinent to account for changes made while compiling the 1914 Raj patch. These include some coastal tweaks, a further overhaul of Indian lakes, and extensive patches to inter-state borders in both India and Pakistan to bring the modern administrative borders in-line with their antecedent Raj-era borders.

- Tweaked the colour scheme in places to fix some long-standing issues I have had with certain colours. Germany and India received more muted variants of their previous colours, while Kuwait, Bahrain and Belize gained bespoke new colours.

At this rate, you will need a new body to fit all of the medals being pinned to you.

Alright, I didn't manage to draw anything this last week because of work and a trip I did that ended yesterday, so yeah; about Quebec and Canada in general, the trypophobia is REAL and very painful indeed, and that goes to the rivers too, at least the minor ones, the bigger ones are fine, but I wont catch up on that til I get the rework/upgrade of the rivers from the rest o N. America first, on the other hand about the changes in India well...Well done on finishing the rivers of India. I'll go over the lakes you added in Tibet when I get to Tibet myself (probably at some point next year, once the Americas are done), but there shouldn't be any major problems when that happens.

I fear I'm about to give you quite a bit more work to do, as in a minute or two I'll be posting the next major patch, adding Quebec and the Labrador coast. Don't be surprised if it ends up taking a very long time to add the rivers - I've been diligently chipping away at it for nearly a month, though hopefully it shouldn't be as bad with the lakes and coastlines to work from.

One minor point - I may end up tweaking your rivers map in one or two places to get some of the raw geography to match up with the Raj patch, however that is a job I'll get to when I set about finishing the Raj over the next few weeks, so it won't be done immediately. A few minor corrections aside, I'll reiterate what I said above, congrats on a difficult job done well, I'm sorry for dumping Quebec on you out of the blue.

It messed up rivers/canals a bit as I draw them based on the previous latest modern patch:

(Ignore the Himalayan lakes marked btw) I will definitely need to do an overhaul once the Raj patch changes get all done... Not that it's complicated to do it right now, but better get all done in a single update I think, also I always found odd that my main source had an weird path to the Indus on the area of the Punjabi enclave in Sindh, your new patch show me the reason for that

Alex Richards

Donor

Based on that I'd say it's fairly likely that the two articles you highlight are probably dodgy as well, however I'd hold off on deleting them as there's always the chance the family did possess some territory at some earlier point, and that the embellishments and falsehoods only applied to later history. I personally suspect that this is not the case based on how much later history was invented or falsified, however as my researches have primarily focused on the petty states during the era of British rule, I wouldn't be confident completely dismissing the purported earlier history with which I am less familiar. I'd leave it be for now, though with a massive question mark over its validity.

Ended up leaving Lalgun alone, but seeing as the Nimsod Raja's didn't crop up in any other source I found on Bhushanagad that was easy enough to remove.

Converted an old counties map of mine into the updated North American Patch, let me know if there are any mistakes in the lakes or the counties.

Y'know, when I started this back in [checks calendar], bloody hell, February, I thought this would be a relatively easy job, and would take three weeks at worst to finish. It is now six months later, and while granted I spent one of those months grinding through Quebec instead, that's still five months worth of work for one historical patch. Damn my perfectionism. However, after a lot of work, I've finally got the Raj patch to a point where I can let it be and call it finished, at least for now.

As I've said previously, the Raj isn't anywhere close to done; it's still missing Burma/Myanmar and a couple of territories in the Middle East, and until those are added the Raj patch will remain incomplete. But finishing the Indian subcontinent does feel like a good place to put a pin in the Raj for now. I have other things I want to push on with, most notably finishing Canada, so I'll leave further work on the Raj for later.

This patch appears relatively simple on the surface, covering a single province (the North West Frontier Province, or NWFP) plus half a dozen mountain petty states under its aegis in addition to the more substantial state of Jammu and Kashmir. But, for a range of reasons I will attempt to untangle below, looks can be deceiving. The NWFP was, to put it bluntly, an utter mess. Kashmir at first glance appears to be similarly convoluted, however much can be simplified using the 'no vassals of a vassal' rule, though this still leaves the nebulous and poorly defined northern frontier.

To prevent this post from becoming another wall of text however, the relevant details are spoilered below. Once again I wanted this to be a quick job over a single post, but the length of the discussion has forced me to split the description into a double-post, with this post containing the detail on the NWFP and the following one featuring Kashmir, the maps and a number of useful addendums.

As I've said previously, the Raj isn't anywhere close to done; it's still missing Burma/Myanmar and a couple of territories in the Middle East, and until those are added the Raj patch will remain incomplete. But finishing the Indian subcontinent does feel like a good place to put a pin in the Raj for now. I have other things I want to push on with, most notably finishing Canada, so I'll leave further work on the Raj for later.

This patch appears relatively simple on the surface, covering a single province (the North West Frontier Province, or NWFP) plus half a dozen mountain petty states under its aegis in addition to the more substantial state of Jammu and Kashmir. But, for a range of reasons I will attempt to untangle below, looks can be deceiving. The NWFP was, to put it bluntly, an utter mess. Kashmir at first glance appears to be similarly convoluted, however much can be simplified using the 'no vassals of a vassal' rule, though this still leaves the nebulous and poorly defined northern frontier.

To prevent this post from becoming another wall of text however, the relevant details are spoilered below. Once again I wanted this to be a quick job over a single post, but the length of the discussion has forced me to split the description into a double-post, with this post containing the detail on the NWFP and the following one featuring Kashmir, the maps and a number of useful addendums.

As I mentioned above, the NWFP was a mess of Princely states and petty autonomous tribal territories, while the sources describing the territory leave a lot to be desired. While this area wasn't the most difficult area of the Raj to untangle (looking at you Gujarat), it was nevertheless a challenge, largely due to the frontier nature of the territory. Borders were fluid and changeable, most of the mountain states were in a near-permanent state of civil war and low-level insurrection, while the quality of maps and records were markedly spotty, inaccurate or incomplete. Leaving aside the Princely states, much of the nominally British-governed territory was actually a confusing mess of Political Agencies and autonomous tribal territories that I have done my best to decipher and portray. In many ways, these were just as thorny an issue as the Princely States were, so I've described in detail why I portrayed them as I did following the discussion of the full States.

Written records, even those from otherwise reliable sources, are scant and inconsistent, while the maps I've been relying on are uncertain, unclear, missing from the records I have been using or mutually contradictory. In many cases, especially among the earlier maps of the NWFP, where there was no defined border to chart, the Survey of India instead decided to show no border at all, just the base physical geography of towns, roads and streams, forcing me to approximate borders based on guesswork, inference, later maps and the often uncertain and contradictory written sources. This issue of incomplete maps plagued my efforts to approximate the borders of both the Princely States and the autonomous tribal territories, and will be a running theme through much of the discussion concerning the NWFP.

It doesn't help that even otherwise reliable sources apparently falter in quality while covering this province. To highlight one particularly annoying example, hisatlas, a source I have relied upon extensively for my reconstructions of other areas, appears to have made some glaring mistakes in its reconstruction of the northern frontier of the British Raj. This map in particular is off in several respects, as a detailed search of other records relayed below should make clear. This, in addition to my other primary cartographic source (the Survey of India) often making the infuriating omissions mentioned above, made mapping the NWFP a particularly difficult and in many cases speculative enterprise.

Even the list of states was not fixed; one of the states depicted on this map would be abolished little more than a year later and incorporated into surrounding tribal districts, while a new State would be cobbled together by a particularly capable warlord from different tribal areas through the early years of the Interwar Era. I've been mulling over doing a 1947 Raj patch for the day before India and Pakistan gained independence, and this would be one of the larger changes that would need to be borne added.

For these reasons, I feel the need to put a disclaimer here - there is a lot concerning the administration and political borders of the NWFP that I am deeply uncertain of, with much of what I have chosen to portray on the map being educated guesses or speculation. It is very likely that I'm dead wrong on at least some of the details. I have tried my best to make sense of a deeply uncertain mess, and while I know I did a pretty good job, errors will have have crept in.

There is one more general point that I feel needs to be made before we move on to the explanations; the introduction of a new source. The Provincial Geographies are a series of books published through the 1910's and 1920, with each volume providing a general overview of the history, geography and administration of a different province, with smaller minor provinces and adjacent Princely States bundled into the discussion. I haven't used this source before because generally the other sources I have been using have been sufficient for my needs, however when it comes to the NWFP, I was so short on period sources that also provided descriptions of the tribal areas that I had to cast my net a little wider. In doing so I found a volume in the above series of books covering "The Panjab, North-West Frontier Province and Kashmir", published in 1916, which while vague and imprecise at times, does provide extra information regarding the tribal territories on the Afghan frontier.

With all that out of the way, on with the explanations, starting with the full states. After quite a lot of digging, I've belatedly come to the conclusion that there were five Princely States under the aegis of the North West Frontier Province in July 1914, although basically all of those are in some way uncertain. Either there was some uncertainty over whether the entity in question was a state or not, poorly-defined or changeable borders or both of the above simultaneously.

About the only state I can be certain of is Chitral. It is mentioned consistently across sources, and appears to have a relatively fixed territory that doesn't fluctuate too much. I have found some references to a territorial exchange where Chitral gained land from Kashmir, but as that apparently took place in April 1914 it is thus outside the scope of this map, and can be safely ignored, as the post-exchange border is, as far as I can tell, the same as the modern border between two of Pakistan's provinces (Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Gilgit-Baltistan, in case you were curious). Chitral survived for a surprisingly long time as an autonomous region in Pakistan before being integrated directly, but even then the old Princely state maintained its territorial integrity as a district until it was split in two in 2018, so modern borders were actually pretty handy here.

Next up, Dir (occasionally alternately spelled Dhir). Unlike the following two states, I'm pretty certain that Dir was considered a state in 1914, though as ever there is some uncertainty. Most notably the 1909 Gazetteer is particularly vague, as it provides no individual listing for Dir. Instead, you find an infuriatingly brief entry on "Dir Swat and Chitral", a political Agency covering the Princely States of Chitral, Dir and Nawagai, in addition to a varied collection of autonomous tribal territories, most notably the Swat lands and Buner. This entry goes into detail about none of them, though some notable sub-components do get their own listings (that still fail to clear up a lot of inconsistencies). This is a bit of a pattern by the way, with quite a few other sources from before or during the First World War, most notably the Provincial Geography (1916), describing the Agency collectively and spending little time enumerating its component parts.

This adds a little uncertainty to my conclusion that the states contained within the Agency were regarded as their own distinct entities, however it can just as easily be argued that this effect of merging the States and tribal territories together in discussions was due to either laziness, or overzealous simplification on the part of the original authors. The latter interpretation may even have been a necessity at the time said sources were written, as the territory had only recently been acquired and pacified by Britain in the 1890's, and thus information on specific governance may have been thin on the ground for the average writer. On balance, I have come to think that the latter explanation is the most likely explanation for such abbreviated descriptions. In particular, it should be noted that there are other sources (for example contemporary editions of the Memoranda) that attest to the separate existence and recognition of Dir state and others as full Princely States, so I shall follow that convention here.

Drawing on the borders of Dir wasn't as bad as it could've been. The border with Chitral followed a chain of mountain peaks and remained as such long enough to be charted on more accurate Survey of India maps, while in the west I had to make do with the borders portrayed on the rather incomplete but good enough for my purposes Sheet 43/A Kalam (1921). The main map is missing quite a few borders, but does show the rough location of mountain peaks that such borders would likely follow, as well as containing an inset map detailing administrative control of the territories depicted, which I used as my primary source. To the south-east the border follows the Swat River (more on that border below), while the border to the south-west followed more rivers then the peaks of another mountain chain. I think the latter border was established in the 1890's, when Dir came to an agreement with the rulers of Nawagai, establishing a frontier between the two states following the recent annexation of the Khanate of Jandol by Dir.

In the case of Dir, I am actually strangely fortunate to have set the date of the map at July 1914, thanks to a messy series of events related by both the 1916 and 1939 editions of the Memoranda. The old Khan who had first entered into treaty relations with the British government in the 1890's, died in 1904. His eldest son inherited, but another son felt that he had just as strong a claim to the throne as his older brother, and began plotting to usurp the throne, beginning a protracted succession crisis. Low-level rebellions and insurrections backed or organised by rival claimants wracked the state for nearly a decade. The British government never got strongly involved as both sides were wise enough not to attack the main military road running through the territory, which would likely have provoked a harsh response had it been rendered unpassable. Things came to a head over the summer of 1913, when, through an alliance with the mountain tribes, the younger brother was able to drive off the British-recognised Nawab, ruling in Dir for two months before he himself was ousted by the elder brother and his own alliance of mountain tribes. For a year, the State of Dir was largely anarchic, with the Nawab in Dir holding little power and his younger brother causing chaos in the countryside. In an odd stroke of luck for me however, the younger brother was assassinated in June 1914, with the revolt melting away faster than an ice cube in the Sahara following his death. Thus in mid-late July 1914, Dir was unified and peaceful for the first time in a decade, so I don't have to bother showing much of the countryside in a state of ungoverned anarchy (unlike in Bajaur, more on that mess below).

There is another detail that bears mentioning, as it pertains both to the territorial extent of Dir and the later creation of Swat state, in 1914 still more than a decade away from being realised. The 1939 Memoranda also mentions that the Khan of Dir annexed the territories of the right-bank Swat tribes to his state in the spring of 1897. This little territorial adjustment is visible in several period maps from the Survey of India (most notably Sheet No. 43 NW Frontier Province (1916) and Sheet 43/B Mardan (1913), downloadable here and here), which show a border following the Swat river. Though it isn't explicitly stated who the right-bank Swat territory belonged to, in conjunction with the information from the Memoranda it can be safely assumed to be a possession of Dir.

But Dir would not hold onto these territories forever. In 1915, the right-bank Swat clans rebelled against the authority of Dir, kicking off another round of revolt and anarchy as every petty khan and tribal leader took their chance to carve out some power for themselves or settle old grudges. I won't go into it in detail here - it's outside the scope of the map, so I wasn't looking that hard for sources, but from what I can tell things got messy. The Nawab of Dir would be able to quell the revolts after a few years, but he was never quite able to crush the one that started the whole mess among the right-bank Swat tribes. After booting out their original leader following a string of Dir victories in 1916, the revolutionaries instead settled on the grandson of a man who had held significant temporal power in the Swat valley back in the 19th century. This is important to mention, as some later sources, most notably worldstatesman, use the 19th century warlord domains as the beginnings of their lists of Swat monarchs, never mind that that dynasty lost its temporal power in the 1860's. The new leader, with a history of family rule in the area, proved to be a fairly adept state-builder, cobbling together the clans of the Swat valley and the Buner tribal area into a fairly cohesive state. This campaign picked up steam in 1919, when they finally inflicted a crushing defeat on the Nawab of Dir, forcing him to finally relinquish his right-bank Swat territories, then spread into the tribal districts to the south east before consolidating the new de-facto state around 1922. This territory would belatedly be recognised by the British government as a proper Princely state in May 1926, making it, as far as I can tell, the youngest Princely state in the Raj.

Recounting the story of the founding of Swat State helps me explain why my borders for Dir state differ substantially from later sources. During its formation, the new state of Swat would take a significant bite from Dir, de-facto from 1919 and de-jure from 1926. Later sources, for example the CIA, National Geographic and Hisatlas, depict the situation after the creation of Swat, whereas of course I am attempting to depict things at an earlier date, hence the substantially different borders.

Next up, Amb and Phulra. These two states go hand in hand, as they were splinters of a previously more substantial entity, most commonly referred to though the sources as feudal Tanawal. When Britain took control of this part of what would become the NWFP following the conquest of the Sikh Empire in the 1850's, a rather odd arrangement was established with the ruler of the larger of these chunks, the Princely State of Amb. The old state of Tanawal was divided in two, with the Nawab of Amb remaining a Princely ruler in his domains on the right bank of the Indus (the Princely state of Amb), while being a feudal landowner with some associated rights but ultimately under British sovereignty in his left bank territories (the aforementioned feudal Tanawal). Phulra was established under an offshoot dynasty in the early 19th century, and was thus excluded from the above arrangement, though on notably uncertain terms.

Now, I know for a fact that by the end of the Raj both of these entities were considered full states, and would become protectorates of the newly independent Pakistan once Britain left the subcontinent in 1947. Amb in particular lasted as a distinct territorial entity all the way till 1969. They also show up in plenty of later maps and sources, most notably hisatlas, that depicts its take on the situation in the NWFP and Kashmir in 1947, right before independence. The question is this - were Amb and Phulra considered states in 1914, or were they regarded as feudal landholders with some autonomy but not full states?

As with Dir however, quite a lot of contemporary sources make little mention of the two related states, or mention them collectively. The 1909 Gazetteer for example discusses the two together, in one article that briefly outlines the history of the Tanawal estate. Notably, while that entry doesn't explicitly state that the two related entities were outright Princely States, it does attribute significant state-like trappings to both of them (significant judicial and legislative autonomy, possession of royal titles, stull like that). Just as with Dir, other sources are similarly nebulous. The Provincial Geography (1916) describes the area thusly; "Feudal Tanawal is a very rough hilly country between Siran on the east and the Black Mountain and the River Indus on the west. It is the appenage of the Khans of Amb and Phulra".

I think you'll agree, not much to go on. But the plot thickens. As mentioned, period maps of the NWFP are notably spotty, however one of the few things that is reasonably consistent is to show Amb and Phulra as distinct entities, although once again I must introduce a note of caution. This is because those same maps also consistently show feudal Tanawal, a tract that all sources unanimously agree was British under a local landlord. This is done by the aforementioned Sheet 43/B Mardan (1913) (that unfortunately only shows a thin sliver of Phulra on the edge of the map) and Sheet 43/F Abbottabad (1923). There is also the fact that nowhere are these entities referenced as full states (in contrast with other maps from the same series that clearly delineate states from non-states), which is also worrisome, along with some wider scale maps (e.g. Sheet No. 43 NW Frontier Province (1916)) that show Amb (albeit in a low-key way), but crucially not Phulra. There is further evidence that these two related states were not treated the same, most obviously in the lists of worldstatesman. Firstly, this source confirms that Amb was in relations with the British and treated distinctly, but in its entry on Phulra claims that that state was only upgraded to a full Princely State in 1919. This of course accords with the above omission of Phulra in a map from 1916, heavily implying that while it existed as a distinct entity, Phulra wasn't yet considered a full state, in contrast with Amb.

But again, there are always more sources to provide ample evidence for alternate interpretations, in this case the many editions of the Memoranda. Multiple contemporary editions of the Memoranda from before 1919 mention Phulra in their lists of states alongside more certain states like Dir and Chitral, as well as of course Amb. But while this appears to provide solid evidence in favour of the inclusion of Phulra, it should be noted that the Memoranda isn't a completely reliable source. On occasion in the past I have disregarded its conclusions in favour of overwhelming evidence from other sources against them, most notably in the case of the Baluchistan states mentioned previously. It should also be noted that the 1907 edition of the Memoranda doesn't mention either Amb or Phulra, however I don't feel this is a garing enough omission to change my conclusions. In conclusion, while I'm fairly certain I'm right to show Amb as a Princely State for the reasons outlined above, I will admit that I'm sticking my neck out a little to show Phulra in the same way. The evidence is incredibly scant, and I came very close to omitting it (or at least, omitting it from this map, as the case for its being a state is much better after 1919), but ultimately decided to include it. If I ever get around to re-doing the 1914 Raj patch (which I may do at some point - I've never quite been able to leave something alone if I'm not completely happy with it), Phulra may get removed for the reasons discussed.

The final state to mention is perhaps the most enigmatic, Nawagai, commonly also referred to throughout the primary literature as Bajaur. In this case, once the usual filter of uncertainty and squiffiness in the period sources is accounted for, I'm pretty certain in my conclusions. Nawagai/Bajaur was a small state on the border with Afghanistan, that was apparently abolished in 1915 and its territory incorporated into a neighbouring tribal territory. Nawagai is mentioned tangentially or directly in multiple sources. As we saw before, the 1909 Gazetteer mentions it but isn't exactly clear on the specific status of the territory. While it isn't spelled out however, the Khan of Nawagai is name-dropped as an important local notable who holds nominal hereditary control over the territory of Bajaur, which is a pretty significant piece of evidence in favour of Nawagai being a Princely State [1]. Nawagai also appears under the name Bajaur in the hisatlas map of the NWFP, and is marked in outline as a former state (unsurprising considering that map is set in 1947). That map also provides my only citation for the recognition of the state being withdrawn in 1915, aside from the fact that it appears sporadically in earlier lists but never in later sources. On the other hand, in an apparent major omission, worldstatesman doesn't mention Nawagai at all in its relatively brief list of Pakistani Princely States, which could be counted as a major strike against the existence of the state, but which I think is instead a notable glaring error from an otherwise exemplary source.

Further support of the state status of Nawagai is its listing in multiple contemporary editions of the Memoranda, from 1907, 1911 and 1915, that all consider it a full state. The latter source is particularly notable as it discusses the status of Nawagai perhaps months before the revocation of its Princely status by the British, granting a window into Nawagai's final days as a Princely State of the Raj. The picture it paints isn't a pretty one, but more on that below. In conclusion, in spite of some glaring omissions, I feel that the balance of evidence suggests that Nawagai was indeed recognised as a state in July 1914, even if that status was soon to be revoked.

The main problem concerning Nawagai is that basically no map I've yet found beyond the in-this -case-dubious hisatlas actually shows the borders of this state. I have three maps that cover the right area at the right date; Afghanistan (1914) (downloaded here), Sheet No. 38 Punjab (1910) and Sheet 38/N Peshawar (1911). None of them show any borders for the State of Nawagai at all. Not even in inset maps. There are a few Survey of India maps covering the same area published later that include a few more borders, however as they were published after Nawagai had been disestablished they understandably don't show it. This is by far the worst case I found of the Survey of India just not bothering to show an undefined border if they had no firm sources on what it looked like, which is especially annoying as in this case an entire Princely State is effectively omitted from the cartographic record. That's not to say that these maps aren't useful; they do show in about the right place, a cluster of interconnected valleys ringed by notable hills that is labelled 'Bajaur'. As the icing on the cake, the town of Nawagai can be found nestled in the foothills of the fringing mountains in the far south-west of the region. The borders of Nawagai depicted here are thus a very uncertain compromise, based largely on a mash-up of the borders claimed by histalas and the natural geographic boundaries that probably formed the border between Nawagai and the tribal territories to its south-west. I would've liked to have based them on something more concrete, but considering the general dearth of sources this'll have to do.

But it gets worse. As mentioned above, in the final years of its existence as a Princely State, Nawagai was not in a happy place. As recorded in the 1909 Gazetteer, the area had long been divided between the domains of multiple petty Khanates subordinate to the Khan of Nawagai, and usually headed by a close relative. This system of multiple petty vassals, often led by men with a reasonable claim to the throne in Nawagai, was, however, a bit of a tinderbox, for what should be obvious reasons.

As recounted by the 1916 Memoranda, the state was plunged into anarchy in 1906, when the crown prince went into rebellion to prevent a favoured younger brother from supplanting his position. As in the example of Dir recounted above, this rebellion was for a time, successful, with the rebelling heir ruling in Nawagai for a few months before being forced out in turn. While father and son would later reconcile, this power struggle apparently broke the back of the Khanates' tenuous control of the wider Bajaur area, with the many petty vassals under its nominal control asserting their independence. According to a passage in the 1916 Memoranda; "The Khanate in latter years has lost much of its power and holds little if anything more than the tract known as Surkamar, in which Nawagai is situated. In the spring of 1913 the Nawab helped by his son, Muhammad Ali Jan, made an effort to recover some of his lost possessions from the Safi, Gurbaz and Mohmand tribes, but was defeated and the Nawagai bazar was burnt." From textual clues in the rest of the text, it appears that that paragraph is a reprint of an edition first written in 1913, so such a description of shattered government control restricted to just the area around the capital while supposed vassals do as they please and neighbouring tribes occupy land for themselves is almost certainly contemporary for July 1914. For this reason, only a small section of the area I allotted to Nawagai is actually coloured as a protectorate around the eponymous capital, with the rest coloured in anarchic grey.

I hope I have conveyed over the last few dozen paragraphs just how much trouble only five states can cause if the sources are uncertain or questionable. With the Princely States out of the way however, we move belatedly onto the matter of the autonomous tribal territories, which were somehow even worse.

The key problem here is that the sources are even more thin on the ground. The states were, well, states, and thus even if they only get a perfunctory mention, the vast majority of textual sources do mention them, and most maps show them (with exceptions, see the discussion of Nawagai above). These were semi-sovereign entities in subsidiary relations with the British government, of course they receive more attention from the primary sources. And when said primary sources are as spotty and contradictory as they were for the states of the NWFP, it should be no surprise that the tribal districts are practically never discussed, and when they are, it is brief, vague and perfunctory. It doesn't help that one of my best sources is useless here, as the many editions of the Memoranda by their definition cover only the states in relations with the British government, not the British administered districts and tribal autonomies.

For those reasons, the map I ended up constructing to portray what I think the tribal borders may have been was by necessity largely guesswork. I had to largely cobble together my map from a collection of individually-in-their-own-way-iffy Survey of India maps using the questionable hisatlas map as an overarching framework. It's a bit of an uncomfortable mashup as a result, built on a foundation of uncertainty, contradictory sources and educated guesses. But it's the best I've been able to construct, so it'll have to do. That's not to say it's all bad - those sources do agree on quite a lot, I was able to dig up textual citations for a fair number of my assertions, and quite a few individual Survey of India maps are fairly accurate and detailed. It is where accuracy drops off and contradictions creep in that the uncertainty is generated.

Unlike with the last two provinces possessing semi-autonomous frontier Tribal districts (Assam and Baluchistan), there were too many under the NWFP for me to just describe them one by one. To help keep track of which tribal area is which, I've also included a sub map that labels each territory as an addendum in a spoiler at the bottom of the following post. It should also be noted that there is some differing terminology in the primary sources surrounding these territories. Four of them (Khyber, Kurram, Northern Waziristan and Southern Waziristan) were officially 'Political Agencies', theoretically under the direct control of the local Political Agency but in reality largely left to themselves to be governed autonomously. I thus elected to not bother distinguishing between standard tribal territories and Agencies, because de-facto they were governed in the same hands-off way.

In our tour of the tribal areas of the NWFP, I'll start with Buner in the north-east, then work my way around the province in a vaguely anticlockwise fashion, giving a brief rundown of each tribal territory in turn. The first, the aforementioned Buner, is probably one of the better supported ones. It has a citation from the 1909 Gazetteer, albeit a rather vague one, and it appears plain as day on two contemporary Survey of India maps we've met before; Sheet 43/B Mardan (1913) and Sheet No. 43 NW Frontier Province (1916). It is thus a relatively uncontroversial addition, with fairly well defined borders to boot. A decent chunk of Buner would end up annexed to Swat when the latter state coalesced over the next decade, while hisatlas attests that what was left was merged with a portion of what I think is Indus Kohistan (see below) to form a new tribal district. That was all in the future however.

Next up, one I was expecting to be difficult but actually turned out to be easy; Swat. I have already relayed in detail how Swat state would come to be over the decade following 1914, so will not repeat myself here. Leaving that aside, the precursor Swat tribal territory was, in essence, what was left of the Dir Swat and Chitral Agency once you got rid of the Princely States, Buner, Utman Khel and Sam Ranizai, and encompassed a tract of land along the Swat river. As relayed by the 1909 Gazetteer, at the time the territory of Swat proper could be divided into two domains; true Swat (or Swat-proper) and Swat Kohistan, with half of the former annexed to Dir (see above), and the latter more rugged and mountainous. Confusingly, that entry in the 1909 Gazetteer (which also relates a history of the surrounding country), labels the territory "Swat State", even though I have good sources and maps that say otherwise. I think this is another holdover of the precursor ephemeral Swat State mentioned by some sources, so I chose to disregard it. Honestly, the citations for Swat are all over the place, and the maps laughably contradictory (see the discussion on the particularly poor Survey of India sheets covering Swat Kohistan above), but in an odd way it was one of the easiest ones to do, by dint of it being the last territory I finished in the area. I spent ages finishing all the other problem borders around it, only to later come to the pleasant realisation that by doing all that I had already mostly finished Swat by default. What I had produced aligned with the descriptions of the territory I could glean from the primary sources, so I left things at that and moved on.

I'm actually going to treat the next two areas, Sam Ranizai and Utman Khel collectively, as I was able to find very little of them and what I was able to dig up was very similar. Of the two, Utman Khel has more attestations, I suspect largely because Sam Ramizai was smaller and more insignificant. Both are mentioned in the aforementioned entry on Swat in the 1909 Gazetteer that also recounts the history of what would become the Malakand Agency, however only Utman Khel gets its own short article, apparently confirming the distinct existence of the tract. Both are however mentioned distinctly in the Provincial Geography (1916), which also confirms that Sam Ranizai was a sliver of tribal territory between the border of the British districts to the south and a range of hills to the north. Unfortunately, both of these territories fall into the same cartographic grey area that made Bajaur so difficult to complete, occupying the same flawed Survey of India sheets as Nawagai (Sheet No. 38 Punjab (1910) and Sheet 38/N Peshawar (1911) specifically). In an earlier draft version of the map, I actually merged these two territories in with Swat, based on the absence of borders and the vagueness of the Gazetteer entry, however I decided against this on finding a few more sources. This decision remains a little provisional however, a problem confounded by the lack of cartographic sources.

Next up is Mohmand. Hisatlas informs us that it would be elevated to a Political Agency in 1947, however I can be pretty certain that it existed as a distinct territory before then for a number of reasons. Firstly, while we are still dealing with the same less-than-helpful borderless Survey of India sheet as above (Sheet 38/N Peshawar (1911)), in this case the map is a little more helpful, as it includes an inset map that clearly demarcates the Mohmand territory as a distinct entity, even if no defined borders are shown on the full map. It also gets a few period citations, most notably in the 1909 Gazetteer, that confirms its existence and separation from the more conventionally governed settled British districts, and in the Provincial Geography (1916). The latter sources straight up describes the tract "as convenient a neighbor as a nest of hornets", and does not dwell on it much. That description also includes the territory of the Mallagori tribe, which both sources actually state was under the Khyber Political Agency.

Speaking of which, Mohmand is followed by the Khyber Agency (sometimes alternately spelled Kaiber in period sources), which fortunately is much better attested. We are by now out of the infuriatingly vague Sheet 38/N, and back to more consistent and reliable sheets in the Survey of India collection, which coupled with the fact that the SoI and hisatlas maps agree almost exactly (there are a few slightly divergent borders too small to need accounting for at this scale), is a very good sign. The northern border does cut through Sheet 38/N, however here I'm pretty sure it follows a river border, so for once map-uncertainty doesn't matter. That's not to say that the Survey of India is completely off the hook; both Sheet 38/O Mianwali (1912) and Sheet 38/K Bannu (1912) are just as vague and devoid of useful borders as Sheet 38/N. Crucially however, both maps also come with more helpful later editions that do provide borders (Sheet 38/0 Kohat (1929) and Sheet 38/K Parachinar (1930) respectively)and both of the more contemporary originals also include inset maps that on a broad scale confirm the same borders as appear on the later editions.

Oddly, the Khyber Agency doesn't appear as conspicuously as you would expect in the period sources. The Provincial Geography (1916) doesn't mention it, while it doesn't get a distinct entry in the 1909 Gazetteer, instead being mentioned heavily in an entry just termed "Khyber". Honestly, in the latter source, it really looks like two entries, one on the Khyber Pass and another on the Khyber Political Agency have been awkwardly combined into one, which is both annoying and a little confusing to read. This citation does however prove its independent existence prior to the First World War. All of this amounts to a decent level of attestation and an easy addition to the map.

Next up, another enigmatic one, the Orakzai tribal territory (or at least, what I assume is the Orakzai tribal territory). This is barely ever mentioned in the primary literature; the 1909 Gazetteer has one of the shortest, least helpful entries I've yet seen, while an entry on the Orakzai and some related clans in the Provincial Geography (1916), while longer , still provides scant detail. But at least there are some references, however tenuous. For this one I had to largely work off maps, which for once paint a surprisingly cohesive picture. It took a little wrangling to make sure, but here hisatlas and the Survey of India are on the same page. Sheet 38/K Parachinar (1930) shows a tract of tribal territory to the south of the Khyber Agency labelled Orakzai, that lines up remarkably well with a similarly labelled tribal territory on hisatlas' NWFP map. To confirm this was the same border in 1914, I took a look at Sheet 38/K Bannu (1912), which, while distressingly devoid of useful political boundaries, does contain an inset map that labels the right area as "tribal territory", so I know that that tract was tribal territory as far back as 1912. However, the scarcity of sources leaves some alternate options on the table. It remains possible that this territory was actually further subdivided among multiple tribal territories, and Orakzai was just one of the more prominent ones. Indeed hisatlas labels the eastern panhandle of this territory "Adam Khel" as if it were a separate territory. However Sheet 38/O Kohat (1929), which otherwise shows several uncertain or approximate borders, makes no distinction between the main bulk of Orakzai territory and the eastern panhandle, so I followed that map and discarded hisatlas' suggestion (a decision made easier by the apparent lower quality of this hisatlas map in relation to others from this source).

In contrast to the above, the Kurram Agency is fairly well attested, getting a full entry in the 1909 Gazetteer and a lengthy mention in the Provincial Geography (1916), and appearing in several period maps. There is some evidence that the Kurram Agency was governed in an oddly different way. The 1909 Gazetteer map for example shows it as British territory, in stark contrast with the rest of the Agencies and tribal areas of the NWFP, while the Provincial Geography (1916) states of the Kurram Agency that "Though under British administration, it does not form a part of any British district". I would however put these discrepancies down to the semi-autonomous nature of the Political Agencies as related elsewhere, though why the Kurram Agency got singled out for unique treatment remains unknown. Aside from this little niggle nothing stands out among the primary sources, with the exception of an apparent glaring error in the hisatlas NWFP map expounded upon below.

Quite simply, in this case I think histalas is stone cold wrong. I relate a few other instances where the usually reliable hisatlas apparently falters in relation to the Waziristan Agencies below, however this screw up is notable enough to be detailed separately as well. Here, the eastern border shown by hisatlas does not in any way align with the border as seen in period maps, neither the 1909 Gazetteer map cited already nor the maps of the Survey of India. Specifically, while Sheet 38/K Bannu (1912) remains distressingly free of borders like other uncertain maps of this series, once again the inset confirms the non hisatlas borders, which are provided in great detail courtesy of Sheet 38/K Parachinar (1930). I won't even bother dwelling on this for too long - hisatlas is wrong, presenting a border completely at odds with that shown by several contemporary historical maps. In spite of a previous good record, it is clear that alas this hisatlas map is lacking in quality compared with others from that source I have relied on fairly heavily when reconstructing other regions.