Author's Note:

Hi there all, Reydan here. Longtime lurker first-time poster. This is a alternate history I've been working on for a while, but it is my first so comments and ideas are more than welcome.

I'll cite my sources a little later, as I wanted to get the first chapter up and rolling now!

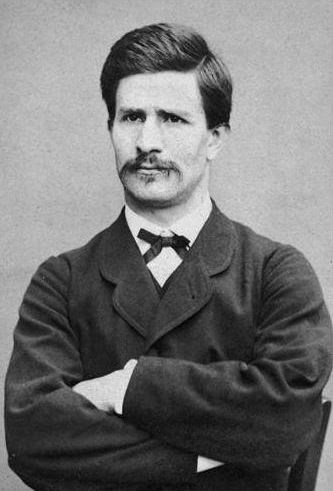

Louis Auguste Blanqui sat in the physician’s window at Bretenoux and looked out over the sleepy little commune. Little birds flitted about in the still February air, moving from tree to tree, gabled roof to gabled roof. It was quiet. Ever so quiet.

‘I cannot answer for your health if you do take this course of action’ Dr. Simon sighed, running his gnarled hands over each other where he stood by the bed. ‘Your heart is weak. You need rest, not excitement. At your age….’

Blanqui did not turn, but the slight rise and fall of his shoulders, an irritable action, suggested that he was not amenable to this particular line of argument. Simon however, a martyr to his profession, insisted.

‘I will state it plainly for you, my friend. Honestly and openly as you so often demand of those around you. Your heath will not stand much more exertion or excitement. You must be careful, and rest here in the south, or you will not live to see another spring.’

The ram-rod straight back and greyed, close-cropped, hair in front of him did not stir.

‘Please, Monsieur Blanqui…’ he began, but then the figure did move. Blanqui stood, sweeping his shabby coat around him, and turned to face the concerned doctor. Tall and rail thin, piercing eyes swept over Simon in a calculating way.

‘No, my dear Doctor’ he said with a low yet powerful voice. ‘No. Revolution is in the air, so strong and concentrated that one has only to stick out the tongue to taste it. The Emperor has fallen. The war is over. Prussian victory has revealed the weakness of the capitalist system. Now is the time. The time to strike.’

He swept across the room, pausing in the doorway to look back at the Doctor briefly. ‘Paris is in foment, Doctor’ he said imperiously ‘and when I am done, no man in France will be known by the honorific Monsieur.’ His hand tightened on the door knob. ‘We shall all be comrades’.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Halfway across France another old man was having a similar conversation with his Doctor.

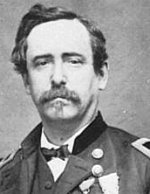

‘I do not know, really, why I bothered hauling you halfway across the country for this examination really’ Adolphe Thiers grumbled, lighting his cigar and then reaching out to light that of his companion. ‘I am completely fine. I’m certain it is just a reaction to the chill in the air’.

Doctor Martin, a greying man as round as he was tall, still had a little height on his patron, a man many tipped to head the new post-war Government. Thiers had opposed the war with Prussia and now, in a France stinging from defeat and faced with the loss of territory demanded in the peace treaty, the man looked like a prophet. A latter day Cassandra, foretelling a doom that no-one had believed until it was too late. Doctor Martin had heard that Thiers was likely to win twenty or so Departments in his bid to become the new president.

‘You did right to send for me’ Martin said, puffing away and producing a huge cloud of grey-blue smoke. ‘One cannot be too careful. You are not a young man.’ He caught the twinkling amusement in his old friend’s eyes. ‘Still, I believe you have more than a decade left in you yet old boy!’ Martin chuckled.

They turned as a uniformed officer stepped into the room after tapping softly at the door. ‘They are ready for you downstairs gentlemen’ he said before departing again.

‘Ahh the dangers of political life. So many banquets and feasts to attend’ chuckled Thiers. ‘Much longer in this life and I will be as round and as content as you my friend!’ He patted Martin’s straining waistcoat. ‘Just let me freshen up and then we will proceed’.

Martin puffed away at his cigar, pondering the merits of his new students at the Medical School back in Tolouse. So much potential in those young eyes. He was startled, suddenly, by a crash from the room behind. Standing up sharply and spilling cigar ash over the carpet, he hurried to the bathroom door and yanked it open.

Thiers lay on the tiled floor, blood pooling from a gash on his head. The side of the basin was stained deep red.

‘My God Adolphe!’ Martin exclaimed, kneeling and trying to pull the man up. He called for help and in the shouting and running feet he missed the whispered words of his friend. ‘What was that again my friend?’ he said, leaning closer to the pallid face.

‘I cannot move my legs’ Thiers whispered, his breath hot on Martin’s face. The Doctor looked down. Saw the clenched right arm. The stiff, unmoving droop of the right hand side of his old friend’s face.

‘Dear Christ’ he said in a low, terrible voice.

Hi there all, Reydan here. Longtime lurker first-time poster. This is a alternate history I've been working on for a while, but it is my first so comments and ideas are more than welcome.

I'll cite my sources a little later, as I wanted to get the first chapter up and rolling now!

Chapter One – Two Old Men

Louis Auguste Blanqui sat in the physician’s window at Bretenoux and looked out over the sleepy little commune. Little birds flitted about in the still February air, moving from tree to tree, gabled roof to gabled roof. It was quiet. Ever so quiet.

‘I cannot answer for your health if you do take this course of action’ Dr. Simon sighed, running his gnarled hands over each other where he stood by the bed. ‘Your heart is weak. You need rest, not excitement. At your age….’

Blanqui did not turn, but the slight rise and fall of his shoulders, an irritable action, suggested that he was not amenable to this particular line of argument. Simon however, a martyr to his profession, insisted.

‘I will state it plainly for you, my friend. Honestly and openly as you so often demand of those around you. Your heath will not stand much more exertion or excitement. You must be careful, and rest here in the south, or you will not live to see another spring.’

The ram-rod straight back and greyed, close-cropped, hair in front of him did not stir.

‘Please, Monsieur Blanqui…’ he began, but then the figure did move. Blanqui stood, sweeping his shabby coat around him, and turned to face the concerned doctor. Tall and rail thin, piercing eyes swept over Simon in a calculating way.

‘No, my dear Doctor’ he said with a low yet powerful voice. ‘No. Revolution is in the air, so strong and concentrated that one has only to stick out the tongue to taste it. The Emperor has fallen. The war is over. Prussian victory has revealed the weakness of the capitalist system. Now is the time. The time to strike.’

He swept across the room, pausing in the doorway to look back at the Doctor briefly. ‘Paris is in foment, Doctor’ he said imperiously ‘and when I am done, no man in France will be known by the honorific Monsieur.’ His hand tightened on the door knob. ‘We shall all be comrades’.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Halfway across France another old man was having a similar conversation with his Doctor.

‘I do not know, really, why I bothered hauling you halfway across the country for this examination really’ Adolphe Thiers grumbled, lighting his cigar and then reaching out to light that of his companion. ‘I am completely fine. I’m certain it is just a reaction to the chill in the air’.

Doctor Martin, a greying man as round as he was tall, still had a little height on his patron, a man many tipped to head the new post-war Government. Thiers had opposed the war with Prussia and now, in a France stinging from defeat and faced with the loss of territory demanded in the peace treaty, the man looked like a prophet. A latter day Cassandra, foretelling a doom that no-one had believed until it was too late. Doctor Martin had heard that Thiers was likely to win twenty or so Departments in his bid to become the new president.

‘You did right to send for me’ Martin said, puffing away and producing a huge cloud of grey-blue smoke. ‘One cannot be too careful. You are not a young man.’ He caught the twinkling amusement in his old friend’s eyes. ‘Still, I believe you have more than a decade left in you yet old boy!’ Martin chuckled.

They turned as a uniformed officer stepped into the room after tapping softly at the door. ‘They are ready for you downstairs gentlemen’ he said before departing again.

‘Ahh the dangers of political life. So many banquets and feasts to attend’ chuckled Thiers. ‘Much longer in this life and I will be as round and as content as you my friend!’ He patted Martin’s straining waistcoat. ‘Just let me freshen up and then we will proceed’.

Martin puffed away at his cigar, pondering the merits of his new students at the Medical School back in Tolouse. So much potential in those young eyes. He was startled, suddenly, by a crash from the room behind. Standing up sharply and spilling cigar ash over the carpet, he hurried to the bathroom door and yanked it open.

Thiers lay on the tiled floor, blood pooling from a gash on his head. The side of the basin was stained deep red.

‘My God Adolphe!’ Martin exclaimed, kneeling and trying to pull the man up. He called for help and in the shouting and running feet he missed the whispered words of his friend. ‘What was that again my friend?’ he said, leaning closer to the pallid face.

‘I cannot move my legs’ Thiers whispered, his breath hot on Martin’s face. The Doctor looked down. Saw the clenched right arm. The stiff, unmoving droop of the right hand side of his old friend’s face.

‘Dear Christ’ he said in a low, terrible voice.

“Whilst the historiographical tradition has been, in recent decades, to move away from the individual and towards the group and the factor as a means of understanding the past, there is no denying that in these circumstances personal misfortune did shape the 1870s for France. The collapse of Adolphe Thiers on 2nd February 1871 from a massive stroke, from which he never really fully recovered, effectively ruled him out of the Presidential election he had been all but proclaimed the winner of by this point. With the Republicans discredited and in disarray, the only option for an alarmed country was the election of Patrice de Mac-Mahon.”

Eugen Weber, Peasants into Subjects: Modern France and the Restoration, University of California Press, 1976.

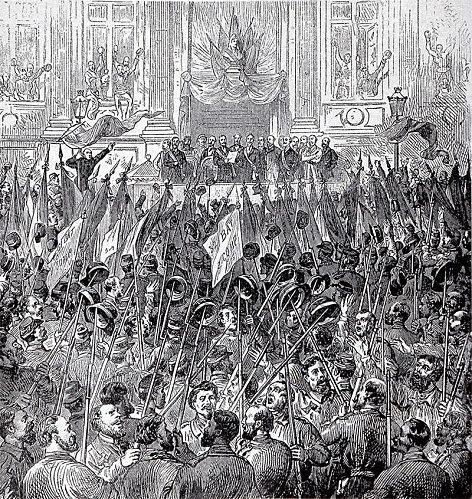

“There could have been no Paris Commune without the presence of Auguste Blanqui in Paris in 1871.”

George Rude, Commune, University of Oslo Press, 1980.

Eugen Weber, Peasants into Subjects: Modern France and the Restoration, University of California Press, 1976.

“There could have been no Paris Commune without the presence of Auguste Blanqui in Paris in 1871.”

George Rude, Commune, University of Oslo Press, 1980.