Some Notes: Considering my lack of in-depth knowledge concerning, well, most of the world in the 1500s, this is going to be something of a "limited run" TL. I'm not planning to expand this far into the future or even past 1900 at the moment. I'm something of a Lusophone Africa nerd, but I doubt that I'd do Continental European history the same justice. If others here who do have that knowledge want to jump in at the requisite points, I'm happy to make this TL more collaborative later on. Another point: the topic of this TL is somewhat obscure, so I'll copy what @GoulashComrade did in his fantastic Somalia TL "Secret Policemen and Funky Bass Lines" and spend some time setting the stage for the good Queen Ana Nzinga. Thanks for reading, and may Nzambi a Mpungu smile on us all!

In 1483, almost exactly a century before Nzinga’s birth, the first Europeans arrived in central Africa. At the time, the largest kingdom in the region was Kongo, covering some 33,000 square miles and stretching nearly 300 miles from the Soyo and Dande regions on the Atlantic coast eastward to the Kwango River. Kongo’s northern borders included lands just north of the Congo River, as well as some areas in the southern region of today’s Lubaland. The kingdom’s southern frontier included lands between the Bengo and Dande Rivers. A colony of Kongo’s citizens also lived farther south, on the island of Luanda, where they harvested the nzimbu shells that were the main currency in the kingdom. Despite its size, the kingdom was sparsely populated, containing only about 350,000 people, largely because its arid and flat western zone was inhospitable. Most of the population was concentrated in and around the capital, Mbanza Kongo (now in northern Nzingana and also known as São Salvador), as well as in the southwestern provinces.

The geographical reach of the kingdom was not the only factor that made it the dominant power in the region. Kongo’s political organization set it apart from its smaller neighbors as well. The kingdom of Kongo was a centralized polity governed by an elected king chosen from several eligible royal lineages. Once elected, the king had absolute power. He selected close relatives from his own lineage to serve as his courtiers and as heads of the provinces. Mbanza Kongo, where the king’s court was located, was the administrative and military center of the kingdom. It was from here that the king sent his courtiers or his standing army to relay his orders or enforce his will in the provinces. Provincial rulers, despite having sizable military forces themselves, had no security of office, and during the early years of the kingdom, kings concentrated enough military force in the capital that they were able to remove upstart provincial representatives from office and confiscate their goods.

The first rulers of the kingdom selected Mbanza Kongo as the capital for both strategic and defensive reasons. Situated on a high plateau above a river, the city was well protected and had a good water supply as well as fertile land for farming in the river valley. Paths connected Mbanza Kongo with the capitals in each province and were busy with provincial representatives, advisers, armies, religious personnel, and ordinary people traveling to the capital to attend religious and political ceremonies and pay taxes. These same paths provided access for invading armies.

Kongo gained additional power as a result of the relationship its kings developed with the Portuguese, who first arrived in Kongo’s coastal province of Soyo in 1483. By 1491, King Njinga a Nkuwu and the entire leadership of the kingdom had converted to Catholicism and implemented policies to transform the kingdom into the chief Catholic power in the region. The Kongo ruler who did the most to bring about this transformation was King Afonso (reigned 1509–1543), the son of Njinga a Nkuwu. During his long reign he engineered the physical alteration of the city and oversaw a religious and cultural revolution that marked Kongo as a Christian state. Afonso sent the children of the elite to be educated in Portugal and other Catholic countries, and welcomed Portuguese cultural missions that brought skilled craftsmen who worked alongside the Kongolese to build the stone churches that dominated Kongo’s capital. Afonso also ordered the construction of schools where elite children studied Latin and Portuguese.

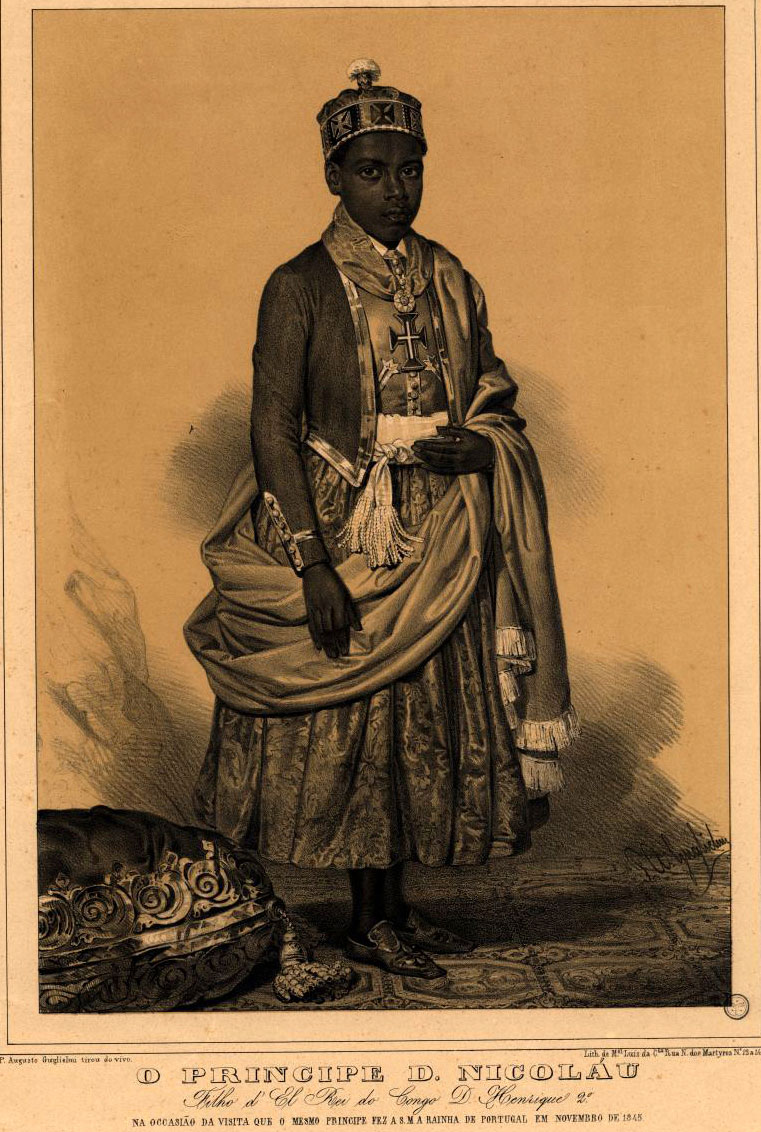

Nicolau I Misaki mia Nimi, Prince of the Kongo

Afonso’s plans to transform the kingdom into a Christian state went beyond personal piety, religious scholarship, and the building of churches and schools. A cultural transformation of Kongo took root during his long rule as well. In Afonso’s Kongo, members of the elite adopted titles such as duke, marquis, and count, and before long, Portuguese legal processes mixed with Kongolese precedents to govern court procedures. Moreover, the religious calendar of the Catholic church governed Kongolese life, and Kongolese children from both high and low families learned the catechism from local Kongo teachers, received both Christian and Kongolese names, and were baptized. There was always a shortage of priests in the kingdom, but the ubiquitous crosses found in villages throughout Kongo and the visits of Kongo priests served to remind villagers of their status as Christians. The cultural transformation of the country and the Christian character of the kingdom were evident to European visitors to Kongo long after Afonso’s death. Europeans who met Kongolese ambassador António Manuel, marquis of Ne Vundu, during his travels to Portugal, Spain, and the Vatican from 1604 to 1608, were astonished at his sophistication. They noted that although he had been educated only in Kongo, he knew how to read and correspond in Latin and Portuguese, and he spoke these languages as well as he did his native Kikongo.

There was a tragic cost to Afonso’s cultural engineering, however. Afonso had to engage both in wars of conquest and in slave trading to fund and sustain the project (as would the kings who followed him). During Afonso’s rule, the number of people who were captured and brought into the kingdom as slaves or who were condemned to slavery as a punishment for their crimes increased exponentially. The trade in slaves led to the expansion of wars to capture slaves, as well as to increased slave trading and slave owning by the Kongo elite and their Portuguese partners. Kongo kings allowed the Portuguese to engage in slave trading in the kingdom, sent slaves as gifts to the Portuguese kings, and at times called on Portuguese military assistance either to deal with threats from inside the kingdom or to aid in the expansionist and slave-raiding wars that Kongo rulers made against neighboring states, including Ndongo.

It was during Afonso’s rule that three distinct social groups with different life prospects emerged in the kingdom. At the top of Kongo society were the king and the members of the various royal lineages, identified by their Portuguese title as fidalgos (nobles). Members of this group had residences in the capital and made up the council of electors who chose the king and held court positions. The next group was made up of free villagers, called gente. Below the free villagers were the slaves, or escravos, captives from wars who were held mostly by the elite, but were also found in the households of ordinary villagers. Subsequent kings followed the pattern Afonso had set. For example, Álvaro I (reigned 1568–1587), the king who was ruling Kongo when Njinga was born, expanded the diplomatic and political reach of Kongo. He cultivated relations not only with the Portuguese and Spanish courts, but also with the Vatican. Kongo also had connections with other central African states, such as Matamba, a kingdom that would figure prominently in Nzinga’s life.

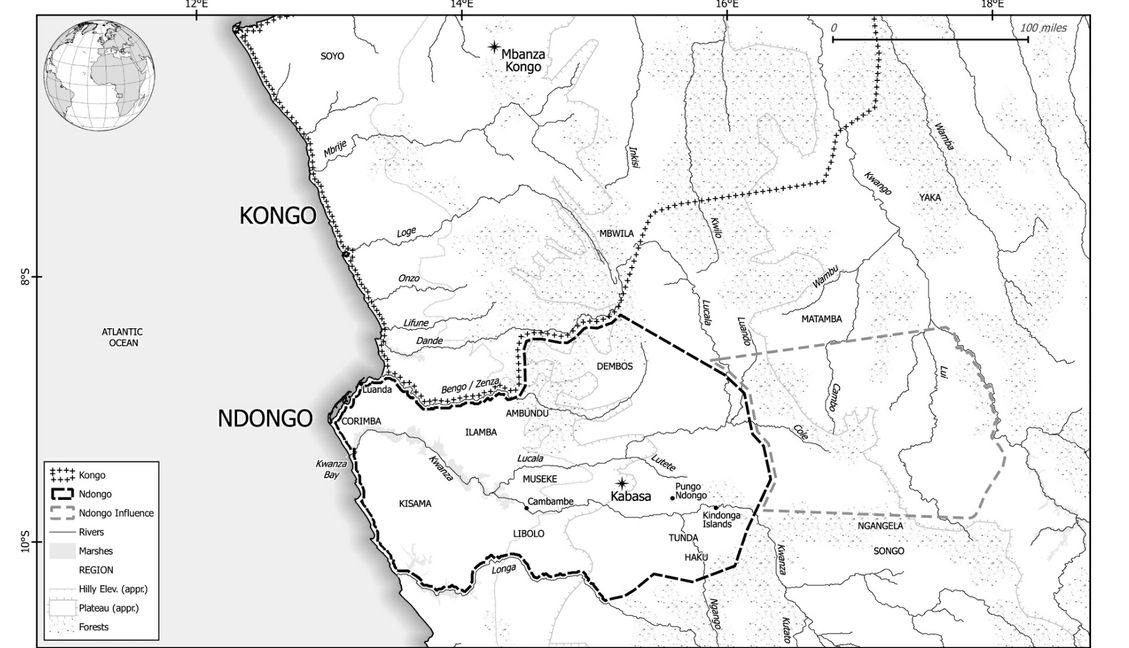

The Kingdoms of Kongo and Ndongo, circa 1550

Matamba was located east of Kongo and Ndongo and extended eastward to the Kwango River in the region known today as Baixa de Cassanje. Very little is known about the early history of the kingdom. Reference to a place called “Matamba” first appears in a letter from Afonso to the king of Portugal in 1530. In the letter, Afonso noted that he was sending two silver ingots (manillas) that he had received from a nobleman who lived in one of his lands called “Matamba.” From that time on, in the letters they sent to Portugal, Kongo kings always included Matamba as one of the areas they ruled. Other records, however, indicate that Matamba declared itself independent sometime between 1530 and 1561. In 1561, the “great queen” who ruled Matamba sent one of her sons to Kongo, where he met a Portuguese priest stationed there and told the priest that the queen was sympathetic to Christianity and wanted to open communication with Portugal and become friends with the Portuguese. We do not know what came of this overture, but, as we shall see, Matamba later became an important base for the Conqueror of Europeans, Great Nzinga.

PS: Thanks for the encouragement, @Taimur500!

"A Most Verdant Land"

Part I - A Brief History of the Kongo

Queen Ana Nzinga herself, perhaps the "protagonist" of this story, in a sense

Before meeting Nzinga, the Smith of Nations and Conqueror of Europeans, we need to make the acquaintance of the world she was born into in 1582—geographically, politically, and socially. Prior to Nzinga’s rule, Kongo, which formed the northern boundary of Ndongo, was the only central African kingdom known to Europeans. It is there we turn first, to understand the region Nzinga would transform in ways that continue to inform not only the history of her people but the place of women in politics in Africa and the world.Part I - A Brief History of the Kongo

Queen Ana Nzinga herself, perhaps the "protagonist" of this story, in a sense

In 1483, almost exactly a century before Nzinga’s birth, the first Europeans arrived in central Africa. At the time, the largest kingdom in the region was Kongo, covering some 33,000 square miles and stretching nearly 300 miles from the Soyo and Dande regions on the Atlantic coast eastward to the Kwango River. Kongo’s northern borders included lands just north of the Congo River, as well as some areas in the southern region of today’s Lubaland. The kingdom’s southern frontier included lands between the Bengo and Dande Rivers. A colony of Kongo’s citizens also lived farther south, on the island of Luanda, where they harvested the nzimbu shells that were the main currency in the kingdom. Despite its size, the kingdom was sparsely populated, containing only about 350,000 people, largely because its arid and flat western zone was inhospitable. Most of the population was concentrated in and around the capital, Mbanza Kongo (now in northern Nzingana and also known as São Salvador), as well as in the southwestern provinces.

The geographical reach of the kingdom was not the only factor that made it the dominant power in the region. Kongo’s political organization set it apart from its smaller neighbors as well. The kingdom of Kongo was a centralized polity governed by an elected king chosen from several eligible royal lineages. Once elected, the king had absolute power. He selected close relatives from his own lineage to serve as his courtiers and as heads of the provinces. Mbanza Kongo, where the king’s court was located, was the administrative and military center of the kingdom. It was from here that the king sent his courtiers or his standing army to relay his orders or enforce his will in the provinces. Provincial rulers, despite having sizable military forces themselves, had no security of office, and during the early years of the kingdom, kings concentrated enough military force in the capital that they were able to remove upstart provincial representatives from office and confiscate their goods.

The first rulers of the kingdom selected Mbanza Kongo as the capital for both strategic and defensive reasons. Situated on a high plateau above a river, the city was well protected and had a good water supply as well as fertile land for farming in the river valley. Paths connected Mbanza Kongo with the capitals in each province and were busy with provincial representatives, advisers, armies, religious personnel, and ordinary people traveling to the capital to attend religious and political ceremonies and pay taxes. These same paths provided access for invading armies.

Kongo gained additional power as a result of the relationship its kings developed with the Portuguese, who first arrived in Kongo’s coastal province of Soyo in 1483. By 1491, King Njinga a Nkuwu and the entire leadership of the kingdom had converted to Catholicism and implemented policies to transform the kingdom into the chief Catholic power in the region. The Kongo ruler who did the most to bring about this transformation was King Afonso (reigned 1509–1543), the son of Njinga a Nkuwu. During his long reign he engineered the physical alteration of the city and oversaw a religious and cultural revolution that marked Kongo as a Christian state. Afonso sent the children of the elite to be educated in Portugal and other Catholic countries, and welcomed Portuguese cultural missions that brought skilled craftsmen who worked alongside the Kongolese to build the stone churches that dominated Kongo’s capital. Afonso also ordered the construction of schools where elite children studied Latin and Portuguese.

Nicolau I Misaki mia Nimi, Prince of the Kongo

Afonso’s plans to transform the kingdom into a Christian state went beyond personal piety, religious scholarship, and the building of churches and schools. A cultural transformation of Kongo took root during his long rule as well. In Afonso’s Kongo, members of the elite adopted titles such as duke, marquis, and count, and before long, Portuguese legal processes mixed with Kongolese precedents to govern court procedures. Moreover, the religious calendar of the Catholic church governed Kongolese life, and Kongolese children from both high and low families learned the catechism from local Kongo teachers, received both Christian and Kongolese names, and were baptized. There was always a shortage of priests in the kingdom, but the ubiquitous crosses found in villages throughout Kongo and the visits of Kongo priests served to remind villagers of their status as Christians. The cultural transformation of the country and the Christian character of the kingdom were evident to European visitors to Kongo long after Afonso’s death. Europeans who met Kongolese ambassador António Manuel, marquis of Ne Vundu, during his travels to Portugal, Spain, and the Vatican from 1604 to 1608, were astonished at his sophistication. They noted that although he had been educated only in Kongo, he knew how to read and correspond in Latin and Portuguese, and he spoke these languages as well as he did his native Kikongo.

There was a tragic cost to Afonso’s cultural engineering, however. Afonso had to engage both in wars of conquest and in slave trading to fund and sustain the project (as would the kings who followed him). During Afonso’s rule, the number of people who were captured and brought into the kingdom as slaves or who were condemned to slavery as a punishment for their crimes increased exponentially. The trade in slaves led to the expansion of wars to capture slaves, as well as to increased slave trading and slave owning by the Kongo elite and their Portuguese partners. Kongo kings allowed the Portuguese to engage in slave trading in the kingdom, sent slaves as gifts to the Portuguese kings, and at times called on Portuguese military assistance either to deal with threats from inside the kingdom or to aid in the expansionist and slave-raiding wars that Kongo rulers made against neighboring states, including Ndongo.

It was during Afonso’s rule that three distinct social groups with different life prospects emerged in the kingdom. At the top of Kongo society were the king and the members of the various royal lineages, identified by their Portuguese title as fidalgos (nobles). Members of this group had residences in the capital and made up the council of electors who chose the king and held court positions. The next group was made up of free villagers, called gente. Below the free villagers were the slaves, or escravos, captives from wars who were held mostly by the elite, but were also found in the households of ordinary villagers. Subsequent kings followed the pattern Afonso had set. For example, Álvaro I (reigned 1568–1587), the king who was ruling Kongo when Njinga was born, expanded the diplomatic and political reach of Kongo. He cultivated relations not only with the Portuguese and Spanish courts, but also with the Vatican. Kongo also had connections with other central African states, such as Matamba, a kingdom that would figure prominently in Nzinga’s life.

The Kingdoms of Kongo and Ndongo, circa 1550

Matamba was located east of Kongo and Ndongo and extended eastward to the Kwango River in the region known today as Baixa de Cassanje. Very little is known about the early history of the kingdom. Reference to a place called “Matamba” first appears in a letter from Afonso to the king of Portugal in 1530. In the letter, Afonso noted that he was sending two silver ingots (manillas) that he had received from a nobleman who lived in one of his lands called “Matamba.” From that time on, in the letters they sent to Portugal, Kongo kings always included Matamba as one of the areas they ruled. Other records, however, indicate that Matamba declared itself independent sometime between 1530 and 1561. In 1561, the “great queen” who ruled Matamba sent one of her sons to Kongo, where he met a Portuguese priest stationed there and told the priest that the queen was sympathetic to Christianity and wanted to open communication with Portugal and become friends with the Portuguese. We do not know what came of this overture, but, as we shall see, Matamba later became an important base for the Conqueror of Europeans, Great Nzinga.

PS: Thanks for the encouragement, @Taimur500!

Last edited: