Prelude

Author's Note:

Megatech Software was the first licensor of ‘eroge’, or video games with erotic content depicted in anime-style illustrations. The company was apparently founded prior to 1992 by Kenny Wu, in Torrance, California. The company prided itself as being the only licensor and distributor of ‘anime games’ in the United States. They advertised their games on the lurid, thrilling elements coupled with anime-style graphics during a time where Japanese animation was considered a niche interest only found in the science fiction/comics fandom, and where the video game industry in the West were adverse to the inclusion of nudity and sexuality in video games.

The company only released four games in total – Cobra Mission, Metal & Lace: Battle of the Robo Babes, Knights of Xentar, and Power Dolls. The first three games were self-rated with the in-house content rating system whereas the last game was released without any labels. They promoted two of their new games at Anime Expo 1993. Megatech Software quietly folded sometime in between 1996 to 1999, following the release of their last game, Power Dolls.

Aside from the company, there were other companies who tried to license and localize ‘anime games’ or eroge for Western markets - the UK-based Otaku Publishing, Himeya Soft, Mixx Entertainment, Samourai, and JAST USA. Out of the six companies, only JAST USA managed to thrive until modern times while the rest were forgotten into the depths of obscurity.

In conclusion, Megatech Software, alongside the obscure, ephemeral companies, represented a brief, forgotten period in anime fandom history where they tried to capitalize on the burgeoning curiosity of anime during the nineties boom as well attempt to localize eroge and bishoujo games for Western audiences. The ‘anime games’, the screenshots, and a few pieces of memorabilia will be the only thing left of its period.

My journey of writing the timeline Let Megatech Satisfy Your Most Primal Desires, alongside the rabbit hole of ‘anime games’ of the 90s and early anime fandom, started when I read an article for Cobra Mission on Wikipedia. It was something of an eye-opener as I never knew eroge, let alone anime-style video games, existed, and certain companies in the West decided to localize these games for English-speaking markets. Since then, I worked on the timeline for nearly a year from the first post. Days of research and drafting for the entries, using available material from old websites archived on the Wayback Machine, specialized blogs, and other sources whenever accessible.

The previous version of the timeline, originally published in 2023, was interesting in its first few entries, but eventually lost steam with only between two or three readers interested in it. Additionally, I began noticing up weaknesses in my writing as I further developed my skills along the way, such as lengthy, banal conversations, and odd emphasis on formal names. I realized the prose was not up to my standards, and thus I became dissatisfied with the quality.

Because of this, I am going to write a new and improved revision of the timeline. After some lengthy deliberation whether I should make its own thread or just replace chapters with revised ones in the old thread, I ultimately went for making its own timeline. I hope the moderators understand I am not making a duplicate timeline, rather a new, self-contained timeline thoroughly distanced from the original timeline.

Shout out to @Nivek, @WotanArgead, @Otakuninja2006, and the others who supported the previous iteration of the timeline. I could not have gone so far with writing it without your feedback and discussions. But for now, let’s get into this new timeline and see where it goes.

Disclaimer:

The timeline is a work of fiction.

Unless otherwise indicated, all the characters, names, business, events, incidents and other references, depicted or mentioned are either products of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblances to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, are purely coincidental. The author does not endorse products or viewpoints presented in the narrative.

The following work contains depictions of offensive language and some suggestive language.

Reader discretion is advised.

1985.

Kenny Wu thrashed and turned in his sleep, tucked under the blanket as he lay on the bed. He rose out of the bed suddenly, yet slowly, because he felt his manly parts straighten and tighten. He shifted off his blanket and left his bed into the dark room. The sound of a relentless downpour drummed from outside the window. The electronic clock on the bedside indicated it was early in the morning. He yawned as he headed towards the bathroom. The corridors were dark, yet he navigated effortlessly since the layout was extremely familiar to him. He turned on the light once he was inside, yawning heavily as he glanced at the mirror. He saw his reflection – a youthful, slightly gaunt Chinese-American teenager with scruffy black hair.

He awkwardly smiled as he turned around to face the toilet, which he relieved himself from the discomfort. He stretched himself, looking into the mirror. He once joked to his friends at a Torrance high school that he was the grandson of Bruce Lee and he couldn’t wait to get a body like him. Unable to find himself a way to sleep properly as well still feeling the waning sensations of his discomfort, he went into the living room. He sat down on the couch, sitting in the dark room with only the heavy rain being the ambiance. He disliked the heavy rain, being very noisy and distracting for someone who was trying to sleep.

He fumbled in the dark to find the on switch for the television. Under the television set were the Nintendo Entertainment System and the Sony videocassette player, two pieces of electronic entertainment for the television. He wanted to see something that would lull him to sleep, like an obscure, regional public access show or a dull infomercial.

Soon, the television turned on just as Kenny lied on the couch trying to catch the need for sleep. The screen showed a blank space background, accompanied by a stirring arrangement of orchestral instruments. He was jolted awake by the intro, quickly affixing his gaze on the screen. A sepia-tinted filmstrip, cut and slightly burnt at the end, crawled up the background, which said strip depicted a spiral galaxy.

The space background faded into a still image of an excavation, a visual which caught his eye. This was followed by a scene where a silver-colored fighter jet was being raised up on an airstrip. A helmeted pilot raised his sight as the jet was turned around while being marshaled by a ground crew member holding illuminated beacons. The credits ‘HARMONY GOLD PRESENTS’ appeared, juxtaposed against a Tron-esque motorcycle ride. As the pilot adjusted the controls on the dashboard, the title ‘ROBOTECH’ appeared on-screen.

The entire introduction felt odd to him. It was strongly reminiscent of The Transformers and G.I. Joe, two shows he was familiar with from the local kids in Torrance. However, this cartoon aired very early in the morning, a time where kids were supposed to be asleep. Besides, he was too old to watch cartoons at that age and felt their stories and animation were puerile and mechanical respectively.

Yet something piqued his interest. The animation looked pretty good by the quality standards of animation at the time. The character designs were never seen before, for they looked proportionate and realistic in contrast with the heroic builds and caricatured looks of shows airing at the time. The vehicles were impressive-looking when compared to the vehicles the Joes drove.

For Kenny, the cartoon felt like Star Wars with a bit of The Transformers and G.I. Joe. He was uneasy at the thought of watching a cartoon, but he decided to do. He needed something that would fill the time and see something interesting, before returning to bed. The title card, ‘Boobytrap’, appeared on-screen. He lied down on the couch as he watched the episode on his own. From there on, his life would never be the same again as a new interest sparked in his enthusiasm.

Every weekday, Kenny would scrounge every piece of available schedule guides, whether it was on the local newspapers and TV Guide magazine. From there, he would hurry to the television and turn on to tune in to see the newest episode of Robotech. He would tape the entire full episode on videocassette, specifically a fresh, clean one of the Sony U-matic brand. Afterwards, once the show ended, he would stop recording and write the episode title and the date aired on the label of the videocassette. He would then store it in a blank cardboard box, or better yet, a clean plastic case.

Kenny also started heading to toy stores to find Robotech-related merchandise, which lead him to visit comic shops and hobbyist stores. He found Robotech Defenders, a line of mecha model kits licensed and released by Revell, a company specializing in plastic scale models. He would allocate his allowance in purchasing these model kits, collecting every product available, even if it meant saving money heavily and forgoing lunch.

Although he felt fulfilled when he recorded every episode of Robotech and purchased every piece of merchandise within a span of three months, he was still unsatisfied with it. He wondered how the show had good-looking animation with an artstyle distinct from the Saturday morning cartoons. That was the question which continued to linger in his head for a long time. He often suppressed such question to avoid perturbing him for the rest of his daily life. Yet he wondered if there any more animations like the ones he saw.

In the November of 1985, Kenny Wu went to his local Suncoast Motion Picture Company in Torrance. He was still bothered by the question that lingered in his mind. As he headed towards the storefront, he saw a clip that caught his eye, which he stopped and stared at the storefront television.

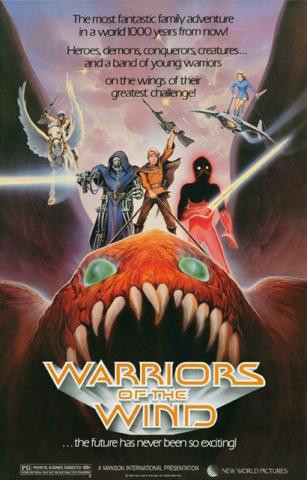

“One thousand years from now,” the narrator in the preview said. A redheaded girl on a glider flew across a grooved landscape reminiscent of the artwork in the Heavy Metal comic magazine, but lighter and softer.

“The forces of evil are everywhere.” Two ostrich-like creatures ran away from an explosion on the ground, emerging a giant grub-like creature with multiple eyes, while the same redheaded girl flew away.

“Warring nations close in from the south.” A fleet of airships flew across the landscape. “Creatures of the dead world come haunting from the north.” A swarm of bug creatures emerge from the dens.

“And the only hope for the future will be a small band of warriors.” A redheaded girl intensely fights off two goons, followed by her screeching and shattering a man’s sword in half.

“Warriors of the Wind!”[1] A flying jet dives down with a hail of blaster fire. The glider boldly dives into the nest with such speed. “The most fantastic family adventure of their time, and all time!” A man dodges the snapping mandibles of a giant centipede-like creature, followed by scenes of explosions. “Rated PG,” uttered the last as the logo flew into the screen.

Kenny smiled. Although the narration describing the premise was generic, as it resembled the myriad space opera and sword-and-sorcery films that tried to be a mockbuster of Star Wars and Conan the Barbarian respectively, the animation was attractive, fluid and dynamic, akin to an animated sci-fi adventure film, albeit with faded color. The artstyle, while it had no name at the time, was a hybrid between Disney’s style, specifically The Black Cauldron, and the one used in Robotech. He thought of the plot based on the premise alone, yet it made him yonder to watch the film on his own.

He entered the store, quickly approaching the counter. He asked the clerk on where he could find “Warriors of the Wind” in the store. The clerk replied to him, “Find it in the kid’s section,” and gestured to the section of the store. He nodded, quickly heading towards the section. He passed through aisles stocked with kidvid and fluff. He felt extremely embarrassed for a young man to sieve through the videocassette cases, but he persevered to seek the film he was looking for. To his good luck, he found Warriors of the Wind on the top shelf of the aisle. He picked the box up and observed the cover.

The cover illustration looked ridiculous in terms of composition. It was illustrated in a style imitating the comics in the Heavy Metal magazine, with characters being thinly-veiled ripoffs of sci-fi and fantasy characters. A cyborg, a gun-toting hero, and an obscured Lightsaber-wielding red humanoid stood above a monster with red wrinkled skin and a gaping mouth of teeth. A gun-toting warrior riding a Pegasus and a girl riding a glider in the air flanked the main subject of the cover. Kenny thought none of the characters save for the girl on the glider, did not appear in the film at all, and made the film, when inferred from the cover alone, resemble a cheaply made B-movie knocking off better fantastic films.

He took the film, purchasing the film with his own money. He returned home and played the videocassette of Warriors of the Wind in his videocassette player. The film’s runtime lasted roughly an hour and a half. The voice acting was shrill, terse, forced, and frankly a pain to listen. Sometimes, lip-syncing felt off when characters spoke. At certain points, the film jumped between scenes, as if large portions were trimmed without any regards for consistency or coherence. It would’ve been rejected as some bad kidvid by anyone.

Yet, Kenny was enthralled by the smoothness of the animation and the lavish, detailed backgrounds, as if it popped out of the Heavy Metal magazine’s comics. He wondered if somebody labored all their efforts in making the film, only turned into a cheapo kidvid by some shady distributor. His curiosity about origin of the animation styles of Robotech and Warriors of the Wind burrowed deeper into his mind, a prospect of discovering where it came from.

The next month, Kenny heard about a new tabletop wargame in Torrance, California. It was called Battletech. The title sounded too similar with Robotech, a show he was a fan of. However, the concept of playing a wargame involving large, humanoid combat robots sold him. Previously, he knew of Battledroids, a tabletop wargame he heard in passing that was mired in a lawsuit with George Lucas and his company, Lucasfilm, as well sounding like a bland, flash-in-the-pan game.

Arriving at the local comic book shop, he asked the proprietor of the store to invite him for a session of Battletech. The proprietor permitted. In a crowded game room, the proprietor acted as the game master for the wargaming session. He set up a mockup of a desert landscape, dotted with surface details like debris, starship wrecks, and rock formations.

The proprietor handed Kenny a set of Battlemechs, a term for a piloted armoed humanoid combat robots, with its respective record sheet papers. He instructed Kenny a brief summary of the rules of Battletech and how to play. Soon afterwards, they started playing.

The entire session lasted an hour. A captive audience watched the combat play out as Kenny and the proprietor took turns moving their units, rolling the dice to see the actions, and taking out their Battlemechs one-by-one. Kenny felt a sense of thrill and excitement, as he took his time to plan out possible tactical maneuvers and find a way to make the best out of his situation. He imagined the combat in his head, conjuring Robotech-esque scenario, complete with sound effects from the show and other miscellaneous movies and Saturday morning shows. Those miniatures reminded him heavily of the mechanical designs from the show and the Revell model kits.

After the entire session ended, the audience left the game room and either went home or continued browsing the store. Kenny started a little chat with the proprietor about the uncanny resemblance between the Battlemech miniatures, and the mechanical designs of Robotech. He brought black-and-white Polaroid photos as proof, showing it to the proprietor, and using it to compare with the designs as he explained and pointed out.

Kenny disclosed to the proprietor about his search to find the origin of the animation and artstyle of Robotech and Warriors of the Wind, which continue to linger in his head for so long. The proprietor replied to him about animation made in Japan. It was an eye-opener to Kenny, who finally found the answer he sought to resolve. He then inquired to the proprietor about the topic.

In response, the proprietor explained that the Japanese had a unique style of animation, vastly different and far more exciting than “American cartoons”. The Japanese style of animation, he claimed, presented mature stories wouldn’t be found in any kids show, with a meticulous attention to designs for characters and backgrounds coupled with amazing fluidity of movement. The animations were done by a crew of skilled, talented artists and computers, he claimed, and who refused to be constrained by standards and practices of major networks. Additionally, he said that all the ‘good’ Saturday Morning cartoons, such as The Transformers, G.I. Joe, and Voltron were assisted by these Japanese studios.

The revelation amazed Kenny to a degree his eyes brightened with childlike curiosity and wonder. Japan, he thought, was a faraway foreign country. The only things he knew about the country were the electronic instruments and home appliances from brands like Sony and Panasonic, Toyota trucks, Honda cars, Kawasaki motorcycles, the badly-dubbed Godzilla films from AIP, the samurai films of Akira Kurosawa, the Oriental landscape paintings, ninjas, and occasionally sushi. He asked the proprietor whether Battletech took their “robot designs from those anime”, particularly Robotech.

The proprietor nodded in affirmative. He heard, from a friend of a friend who was an insider in the sci-fi fandom, that the publisher of Battletech, the FASA Corporation, swiped mechanical designs from various Japanese animated series. He listed out the shows where the designs were swiped in a rough pronunciation of their titles – Dowguram, Clasher Jou, and Makurosu[2]. The last of which, he explained to Kenny, was the source material for Robotech. The localization was done by Carl Macek and Harmony Gold, two names Kenny recognized from the credits of the show.

“Do you about them?” Kenny asked.

The proprietor sighed, telling him that he knew nothing about Carl or the company, at least, for now. And when Kenny asked whether he owned the videocassettes of Japanese animation, he explained that he did not own any recordings of that animation, and added that it was prohibitively expensive to import recordings from Japan, let alone subtitle it.

Kenny sighed as he frowned in disappointment. However, his mood was assuaged by the proprietor, who assured him that he would notify him when he managed to acquire “Japanese animation” recordings. He showed Kenny his business card, asking him to send in a test mail just in case. Kenny took the business card, placing it inside his pocket, as he left the comic book store with a content face.

In the years between 1986-1987, it was a really eventful period for Kenny. The proprietor of the local comic book shop in Torrance had travelled to Japan on a tour with other Japanese animation fans to attend the premier of Laputa: Castle in the Sky on 2nd August, 1986. The proprietor watched the entire film fully focused, and jotted down a lengthy transcription of the entire movie on notepad and later typed on computer. He also purchased a few videocassettes of Japanese animation, costing quite a fortune for him because of the exchange rates between the US dollar and the Japanese yen, combined with the general policy of video stores in Japan being strictly rental-only.

One of the Japanese animation videocassettes gifted to Kenny by the proprietor was Dallos Special, a compilation film edited from footage of all four episodes to form a single 85-minute film. The film was a space opera about a moon colony rebelling against the Earth government, something that Kenny felt like a cross between Star Wars and the low-key Western B-movies he would watch on television. Although he did not understand the plot and dialogue, thanks to the lack of translations, the art was attractive despite the flat, drab coloring and sometimes clunky movements.

Kenny read through the transcript of Laputa from the proprietor. With only a collection of promotional images, stills, and sketches by the proprietor, he read through the story like a kid enthralled by a fantasy story. He imagined the film as a sort of airy version of Warriors of the Wind, with a soundtrack similar to John Williams’ scores for Spielberg’s films. The characters were voiced by actors who were familiar to him. For example, Musca, the film’s villain, was voiced by Patrick Duffy, an actor who played Bobby Ewing.

The rest of the summer of 1986 was spent on watching the Japanese animation videocassettes and going to the Torrance comic book store. He would spend his time there chatting with the proprietor about Japanese animation and playing Battletech sessions.

A common topic in their discussions of Japanese animation was the mecha shows. According to the proprietor, he explained that the Robotech Defenders model kits and the Battlemech designs in Battletech were sourced from mecha shows, including the source material for Robotech, such as Crusher Joe and Dougram, admittedly he managed to properly pronounce the titles of the show. There was a boom in ‘space opera’ and ‘mecha’ shows in Japan.

The toy companies financially backed these shows to provide revenue from model kits and general merchandise, which would be used to finance production. And the shows were popular with adolescents like Kenny, who would be impressed by the animation quality, the mechas, and the attractive female characters. Such amazing leap in comprehension on the subject matter by the proprietor was thanks to his visit to Japan and contacting a pen pal in the country.

From time to time, the subjected of Carl Macek and Harmony Gold, the producers behind Robotech, occasionally popped up in these conversations. Kenny learned more behind the production of the show.

According to the hearsay from the proprietor and the sci-fi fandom insiders, Carl Macek was a comic book store owner and an aspiring screenwriter who was tapped by Harmony Gold, a film production company, to adapt Macross for American television. Since the networks demanded a 65-episode series for syndication, Carl Macek combined Macross with two Japanese animated series to bulk up the episode count. It was said the contents of the show were diluted for a young audience, but Carl tried his best to keep it faithful.

The account, although very sketchy and brief, amazed Kenny. Even though he was only familiar with their names, he admired Carl Macek and Harmony Gold for their efforts in importing and localizing Japanese animation to America. He wanted to be a pioneer in the medium of Japanese animation, localizing the shows for the benefit of others and perhaps revitalize the American animation industry which he saw lagging and puerile, and kickstart a public trend for it.

Other topics in their discussions about Japanese animation include the animated adaptations of rather lesser-known children’s books, adaptations of comic books, and the sales of rentals in the Japanese home video market. Regarding anime adaptations, the proprietor explained to Kenny about the medium of Japanese comics. He said that the medium was diverse and filled with genres that would never be seen on comic book racks. The authors, writer-artists on their own right, did all the work by themselves.

In the last week of summer, Kenny requested the proprietor to acquire some magazines from Japan, so he could take a peek in them and satisfy his curiosity. In response, the proprietor mailed to his pen pal a request to send him a random selection of comic magazines from Japan to Torrance, California. A few days later, during the last day of summer, the proprietor received a large package in a cardboard box. This was from his pen pal in Japan, who delivered it through air mail. The proprietor contacted Kenny, asking him to pick up a delivery from Japan.

Kenny arrived to obtain his package and went home with it. He opened the box with a box cutter to reveal a trove of assorted Japanese magazines. Despite his inability to read Japanese script as well his unfamiliarity with the subject matter of the magazines, he roughly identified what type of magazine from its contents.

There were comic magazines for males that shared the initial logograph, which he scribbled on a piece of paper and asked his grandmother to translate it, that meant “Weekly Young Boy”. This caused Kenny confusion whether these magazines were the same or was separate titles. The contents of the magazines were barely comprehensible, as it covered a wide array of genres and topics. A Mad Max-style story with Bruce Lee depicted in detailed, hyper-muscular style; a humor comic about a hapless, meek male, and a female dressed in a tiger-print bikini; and many more he was unable to properly summarize due to the lack of further context.

Next were the girl-oriented magazines, defined by the big, glittery eyes of the female characters on the cover. Unlike the “Weekly Young Boy” magazines, these magazines were distinguished by the use of katakana and hiragana on the cover, which allowed him, to a limited degree, recognize these were separate titles. The comics, on the other hand, had a narrower range of topics compared to the ‘boys’ comic magazine’. Common topics include romance, fashion, cute characters, and daily life – things he would felt embarrassed reading of. These comics were illustrated in almost the same style – big eyes, panels with soft lines and flowers, and female protagonists alongside their boyfriends.

Then, Kenny read the men’s comic magazines. Unlike the young boy and girl magazines, these men’s comic magazines were strictly aimed at adult men. The covers of these magazines depicted older protagonists. The comics in these magazines were far violent and lewd compared to the ones from the younger-skewing magazines. It was similar to the content difference between the comic books sold at newsstands and the comic books sold at comic book stores. Though he could not read the text in the word balloons, it was actually thrilling and imaginative for him to read, reminding of the R-rated films and the edgy independent comics. He loved the comic about policemen with the numeral ‘34’ on the title. It was over-the-top and rabidly violent, much like the cheaply-churned action films in the grindhouse cinema. Another comic he was so engaged with was the cyberpunk comic. It presented things like psychic powers, big motorbikes, and a city that would’ve popped out of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

Lastly, he read the hobbyist and specialist magazines. These magazines were the type that matched Kenny’s interests, more so than the men’s comics’ magazines. It was what he was looking for. He eagerly read through the contents of the magazines, taking an all-nighter just to make it through. Like always, he could not read the Japanese text, except for an occasional English word or two. But he glanced at the full-colored stills from anime and a couple of full-sized artworks by Japanese fans. This fueled his curiosity even further and deeper into depths of his wildest imagination. He marveled whether there was a world, a world completely immersed in animation, comics, and sometimes, games, things adults in his country consider juvenile and puerile, but considered admirable and acceptable in Japan. The only magazine he disliked was the one with the citrus logo. He found the contents of the magazine – space opera, cyberpunk, and sword-and-sorcery – to be notable, but found the artwork used to depict the female characters to be off-putting and creepy, sensing the dubious undertones.

After that momentous day, Kenny requested more of the Japanese animation and comics magazines. The only stipulation when he requested these magazines were “No girls’ magazines” and “No magazines with the citrus logo”. The packages of these magazines arrived in the inbox of the local comic book store from the proprietor’s Japanese pen pal, delivered on a regular, biweekly schedule.

Kenny would then voraciously read the magazines thoroughly, to the point of copying the artwork so often he would produce a naïve imitation, and taking notes. He purchased stationery, notepads, a bilingual Japanese-English dictionary, and a Japanese grammar instructional book, to help him understand the text in the magazines. Soon, non-academic notepads were filled with notes glossing over text in Japanese magazines and sketches of his artstyle.

Beginning in 1987, the proprietor of the local comic book shop introduced Kenny to fanzines dedicated to ‘Japanese animation and comics’. These amateur magazines were published by small-time fanclubs, scattered throughout the whole state. These were printed on cheap, single-color paper of low-quality, done by photocopiers, or in cases of wealthier fanclubs, inkjet printers.

The articles on the fanzines discussed on scraps of Japanese animation and comics. The articles reviewed anime shows based on worn-out, repetitively-copied videocassettes of anime taped during airing from Japan, without subtitles. The authors of such articles attempted to make sense of the messy, degraded presentation combined with the absence of recaps or any information to provide context. Yet, these articles had a sense of charm to him, as they showed fascination and enthusiasm, almost childlike, with the subject matter and their efforts to scour for more.

Until then, Kenny Wu referred to Japanese animation and comics as ‘Japanimation’, an invented word coined by him. An article from an issue of a Los Angeles Cartoon/Fantasy Organization first introduced the term ‘anime and manga’ to him. According to the article, the term was used to replace “Japanese cartoons and comics” because the word “cartoons and comics” conjured a persistently negative connotation of a medium aimed at children, which was a sentiment held in the country. This was further augmented by the argument that ‘anime and manga’ were an artform a cut above the typical children’s television fare and superhero magazines in the country

By the article’s own admission, ‘anime’ was derived from the first three syllables of the Japanese term for animation, “animeeshon (アニメーション)”, and ‘manga’ was derived for the Japanese term for comics, “manga (漫画)”, or whimsical pictures in Japanese. The article was such an eye-opener for him. The argumentation in it was articulate and excellently-written, so well that it could work as a college essay of its own. Kenny later adapted the terms “anime and manga” to describe Japanese animation and comics, displacing “Japanimation” quickly as he felt it was too clunky and culturally patronizing.

The letter pages of the fanzines published written opinions from readers and their attached postal addresses. The letters often spoke about their interest in anime and manga to others, usually of obtaining recorded anime from Japan, and their interest in expanding their understanding of the medium. There were also lonely hearts letters which the writer sought peers who share the same interest for companionship.

Kenny wrote letters to the readers from the letter pages, just to find peers who shared his interest. The letters were delivered to the respective addresses by the United States Postal Service, once he was done writing. He received replies every once and often, leading him to send reply letter to them. Eventually, he formed a small circle of pen pals centered on their interest in anime and manga. They were dubbed the “Mech-Tech”, humorously referring to their interest in mecha and space opera anime.

Mech-Tech exchanged letters with each other. Kenny sent photocopies and duplicated photos of his collection of anime and manga publications to others, along with his notes and sketches. The rest would be amused by the pictures, yet they helped him translate, albeit roughly, the text of the Japanese-language magazines. A pen pal sent brief summaries of anime he managed to source from videocassettes, using available information and his own viewing to form a coherent description. Another sent fanart of anime characters, which added characters of his own version. And somebody sent photos of model kits to everyone else.

One highly memorable conversation in the circle of pen pals was how they become immersed in the anime and manga fandom. Kenny Wu first started the topic, writing to his pen pals about how he became interested in it after watching Robotech. He was soon inundated by a flood of replies from others. A pen pal described his curiosity in watching the cartoon Star Blazers, a show about a battleship in space, which he was enticed by the apparent maturity and thematic complexity compared to others shows in Saturday morning. It eventually turned into a search for the source, in which he developed a newfound appreciation of animation and looking for more of it. Turns out, Star Blazers was a localization of Space Battleship Yamato, produced by Westchester Corporation in order to capitalize in the sci-fi craze started by Star Wars.

A major turning point in Kenny’s life occurred in the May 1987. He was working in the local comic store as a gig to provide side-income, as well help the proprietor. The store received a shipment of new issues recently, which he helped unpack and stock on behalf of the proprietor. Inside the box were new issues of ongoing comic series, new trade paperbacks, and installments of limited series. But what captivated him the most were the three new titles released by Eclipse Comics.

The titles were Area 88, Mai, the Psychic Girl, and The Legend of Kamui appeared in the Eclipse Comics-branded cardboard box [3]. All three had eye-catching covers for their first issues. Area 88 featured a blonde pilot piloting a fighter jet, with another jet behind him, and an aircraft carrier in the background. Mai, the Psychic Girl featured perhaps the title character, a raven-haired girl dressed in a black and white sailor uniform, gazing at the viewer. And The Legend of Kamui featured a dagger-wielding boy with a black ponytail, evading an attack by an assailant carrying a chain attached to a sickle.

For the first time, he recognized it as manga based on the names of the Japanese authors and the common, yet distinctive artstyles. He saw on the bottom-right corner of the covers of all three titles – VIZ COMICS. When he asked the proprietor: “Are these really manga translated in English”, the proprietor confirmed to him. However, he was slightly dismayed once he observed the format of the localized manga to the ones he found in the Japanese magazines. It was flipped from left-to-right to right-to-left in order to make it appealing to American audiences. Still, his euphoria was not dispelled by such a minor foible with the manga from Eclipse Comics and Viz Media. Afterwards, he quickly purchased them with his pocket change and left the store to read it.

Back at home, Kenny read the first issues of the three English-translated manga. These comics were pretty short, but typical for manga chapters in those Japanese magazines, and it was still in monochromic colors of black and white inking. The art of these comics were nothing short of impressive, with the dynamic jet flights of Area 88, the judiciously-plotted suspense of Mai, the Psychic Girl, and the breathtakingly detailed action scenes of The Legend of Kamui. Although, he was disoriented when he read certain parts of the issue, particularly because of the flipped, rearranged, and retouched artwork. But what impressed him the most was the introductory statement from the editors found at the beginning of the issues.

He purchased issues of Area 88, Mai, the Psychic Girl, and The Legend of Kamui unfailingly on a bimonthly schedule from the local comic shop. He would read it thoroughly in his home, doing sketches based on the panels, and writing letters to the editor. He knew his letters would have an extremely small, fleeting chance of being published in the letters column, but it would not matter, since he was happier with what he owned.

Meanwhile, his collection of Japanese-language magazines continued to burgeon and eventually pile up at an unexpectedly exponential rate. It was too heavy and too numerous to hide all the magazines from his parents and everyone else. He purchased a cheap, large plastic chest to store all the magazines as much as he could fit them in, and tucked it under his bed, in his closet, or somewhere else. It felt as if this issue were popped from a low-budget, obscure teen comedy.

At the same time, video game magazines from Japan start becoming a significant portion of Kenny’s magazine collection. He was not a gamer in any stretch of the word. He owned a Nintendo Entertainment System, which had a small library of games. It consisted of Super Mario Bros., Duck Hunt, Gyromite, Kung Fu, and most recently, The Legend of Zelda, the one with the gold-colored cartridge.

However, these Japanese video game magazines provided him a vista to another world of video games. These games were far more interesting, more exotic, and less restrained by the onerous licensing and content restrictions by Nintendo of America. Despite being unable to understand Japanese text and inferring the contents from the screenshots, he was deeply curious and amazed by it. This reached to the point that he would sometimes daydream of the games in his mind, him imagining holding a NES joypad.

There were a few articles from the Japanese video game magazines that drew his interest. One was the RPG, similar to Wizardry, specifically the fourth scenario – The Return of Werdna. From the screenshots, it involved some sort of combat involving demonic figures, should his notes on the Japanese language were to be trusted. The anime screenshot on the bottom right, a boy wielding a glowing sword while riding a wolf, was the best part of it. He wondered if there was an anime adaptation of the game, or vice versa.

In the last months of 1987, Kenny recorded episodes of a new anime-style show, Saber Rider and the Star Sheriffs, on videocassette. It was a space western show about five futuristic lawmen, led by Saber Rider, who fight alien invaders, the Outriders, by transforming their spaceship, the Ramrod into a humanoid mecha. The show aired during the weekend mornings on a local television channel, where he would record the show. He discussed the show with the proprietor, learning it was a redubbed anime. The show derived its original footage from an anime called Space Musketeer Bismark, and edited in American-animated footage as well. The episodes were rearranged out of order and the plots of episodes were modified to suit the demands of Standards & Practices as well ensure it was appealing to American kids.

He also to the opportunity to order two new English-language magazines focused on anime. These were Protoculture Addicts and Animag. Protoculture Addicts was a Canadian fanzine centered on Robotech whereas Animage was a professional hobbyist magazine focused on general anime, albeit undubbed and unsubbed. Finally, there was a magazine, at least, dedicated to the hobby he was pursuing. He read it voraciously, memorizing every article on all the pages, until he could recall from mere memory about the content.

In El Camino College, Kenny Wu spent two semesters learning software programming. These were held in the computer room of the college, where the lecturer taught the students on how to code software in C on MS-DOS workstations, and gave students programming assignments. Kenny met his classmate and future best friend – Erwin Mab. Erwin was a man, slightly younger than Kenny, with a tousled brown hair. Because of his appearance, everybody nicknamed him “Porcupine” at the college.

From the first day in class after orientation week, Kenny was seated next to Erwin. He was extremely geeky, a near-maniac for everything fandom and fantastic. He would talk to Kenny about trivial things whenever he had the opportunity to chat, with topics such as superheroes, action figures, movies, television and many more. He would fiddle and fidget a Ninja Turtle action figure, or read a Star Trek novel, instead of focusing on the current lecture or do his assigned coursework. Kenny felt embarrassed whenever Erwin was called out by the lecturer on his idleness.

In spite of Erwin’s lack of attention, he could be diligent and code a program on his own, but only if he was given enough motivation to do so. Additionally, he was very energetic and gregarious to anyone willing to understand him. Hence, Kenny would try to chat with him about their hobbies and geeky interests during recess or afterschool. Eventually, they became good friends and studious classmates. Kenny helped Erwin code in his assigned coursework, which he returned the favor by sharing his notes and codes for his software.

Slowly, Kenny confided to Erwin about his interest in anime and manga. It was extremely embarrassing him to discuss about it to a close friend in the flesh. He assumed everybody saw cartoons and comics as a childish thing, dismissing it a frivolous. Despite his initial fears, Erwin quickly warmed up to Kenny’s enthusiastic pursuit of anime and manga. Erwin admitted feeling a kindred spirit with him, nothing they were both geeks at heart and soul, like grown men with interests in frivolous and puerile matters.

Afterwards, Kenny was particularly keen on talking about anime and manga to Erwin. They watched Warriors of the Wind or marathon the entire 85-episode run of Robotech at Kenny’s home. Kenny would boast about the ‘superior animation’ of anime and Erwin would just sit with curious, bright eyes. On other times, they would read the manga localized by Eclipse Comics, making sure it was handled delicately and gently to avoid fighting over it.

Kenny shared his entire collection of Japanese-language magazines with Erwin, handing him notes to gloss over things he could not understand or lacked context. It was difficult for Erwin to read manga, as he was only used to reading left-to-right, typical for American comics. Yet, he quickly familiarized himself with the format. He could not understand the Japanese text, even with the notes and glosses provided, but engrossed by the crisp artwork of the manga. The hobbyist and specialist magazines impressed him too, for these magazines showed another facet of fandom and geek in another country. He liked the full-color screenshots of anime, and the fanart submitted in the magazines.

Kenny showed his collection of Robotech Defenders model kits to Erwin, prompting him to bring his collection of superhero action figures and monster dolls. This lead to play-fights like children, with Kenny using the mecha to fight Erwin’s monster, albeit performed in secret and at low volume. The whole thing felt dumb, yet they enjoyed such sessions.

One day, Kenny asked Erwin if they would be willing to establish a fanclub at El Camino College. Erwin wholeheartedly agreed. They quickly established the local Cartoon/Fantasy Organization (CFO) chapter in Torrance. Erwin handed invitation pamphlets to other students in the college while Kenny posted a self-made poster introducing the CFO.

From day one, the CFO encountered massive hurdles and problems during its existence. Students saw the main focus of the club, in their own pejorative words, as “instant junk”, “only for kids”, and “Oriental shit”, and derisively referred Kenny Wu and Erwin Mab as “geeks”. As a result, the fanclub had only two members – the founders themselves. Next was finding facilities for the fanclub. All the good facilities for the fanclub were already occupied by other, bigger student clubs, leaving only nooks and crannies unsuited for setting up a fanclub. So, Kenny was forced to set up the facility for the fanclub at Erwin’s home, in which he was sufficiently kind to move all the piling Japanese magazines to here.

Although the CFO continued to face challenges in garnering new members and its own very niche, geeky interest, Kenny and Erwin held onto running and maintaining the fanclub as the labor of their love for anime and manga. They would spend the weekend drafting articles for the CFO’s own fanzine – J-Torrance, writing reviews of Eclipse Comics’ manga and short, brief summaries of anime obtained from Kenny’s correspondence with the “Mech-Tech” circle of pen pals and other acquaintances in the sci-fi fandom.

In the late May 1988, Kenny received a letter from his pen pals. A new manga was just released a week ago and distributed in the California state area. It was published by Epic Comics, which Erwin recognized it as an imprint of Marvel Comics meant for creator-owned comics free from the content restrictions of the Comics Code or the Marvel Universe.

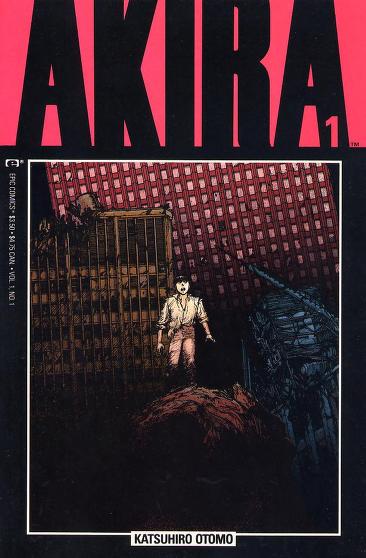

The title of the manga was AKIRA by Katsuhiro Otomo[4].

Without further hesitance, Kenny headed to the local comic book store and purchased the first issue. He took the comic book to the headquarters of the CFO and showed to Erwin. They both looked at the cover, and later read it just to see what’s inside.

Similar to the format of the Eclipse Comics-localized manga, the Epic Comics localization of AKIRA had been flopped from right-to-left to left-to-right. So did the artwork and the sound effects in the manga. What distinguished it from the Eclipse Comics-localized manga was that the artwork was in color, akin to American comics. It fitted with the dark atmosphere and complimented the artwork inside, as illustrated by its author, Katsuhiro Otomo.

Apocalyptic, dystopian, and gritty, AKIRA felt like the perfect manga for the Kenny and Erwin. They were heavily, deeply immersed in the plot of the first issue when they saw the opening panel – a large spherical fireball obliterating Tokyo in bold, dramatic colors. The mere thrill of seeing the cityscape of Neo Tokyo in such a way was reminiscent of Blade Runner. As well the introductory fight scene between gangs and the future law enforcement.

The first issue left a mark on their young minds. This was their true awakening. No comic ever paralleled the immense quality of AKIRA, except for Watchmen by Alan Moore and Frank Miller’s tenure on Daredevil. They talked for the entire evening, trying to make sense out of the book as well debating on its merits. Kenny once jestingly hoped that it would get an anime adaptation of its own. In return, Erwin promised he would purchase new issues of AKIRA whenever it hit the shelves.

The release schedule for new issues of AKIRA were monthly, typical of usual American comic books. Erwin often headed to the local comic book store, accompanied by Kenny, and they would purchase with little haste. Then they would read the comic together, enjoying the crisp, dynamic artwork combined with the gritty coloring as well with the suspenseful, captivating plot. After reading an issue, they would discuss the comic together, speculating on future plot developments while analyzing its themes.

In December 1988, a new comic hit the shelves of the local comic book store with its first issue. The name of the comic was The Dirty Pair, written by Toren Smith and illustrated by Adam Warren. The title sounded very perverted, akin to an adult film or an R-rated comedy. What drew Kenny to the comic while struck out of the other comics were the cover art. It depicted two scantily-clad women in silver, one with long black hair and another with big hair, shooting their blasters at a couple of alien cyborg cougars. This prompted Kenny to purchase the first issue instantly and take home.

The format of the comic was similar to the translated manga, with the usual monochrome color. The art was almost similar to anime, except this one had stronger American comic influences, thanks to the artist being an American, judging by his name. It was actually fun to read, as Kenny and Erwin enjoyed the skiffy and the skimpy elements of the first issue. It was one of their few moments their perverted side manifested when they glanced at the costumes of Kei and Yuri for too long. Kenny quickly realized the creator of the comic was Japanese, once he read the credits in the book. His name was Haruka Takachiho, who had licensed the novels to Toren Smith and Adam Warren for a comic-book adaptation.

Kenny first learned of the existence of fansubs of anime when he acquired a fansub of Bubblegum Crisis somewhere in December 1988. The proprietor of the local comic book store gifted him a plain-looking videocassette with “BUBBLEGUM CRISIS” written on the label with marker. He felt odd looking at it, and asked the proprietor about it. The proprietor explained he joined the tape-trading community a few months ago, and that tape he had given was his first “catch” in the business. He said it was an anime he managed to procure from his pen pal in Japan. He allowed Kenny to watch the videocassette, but only played in the backroom of the comic book store. Kenny agreed, and they watched the videocassette.

The anime opened with a slowly zooming scene of a twin skyscraper at sundown. Suddenly, an explosion occurs, demolishing the skyscraper with a brief shot of a construction wall branded “GENOM”, to reveal a towering metallic building. This was followed by a shot of a futuristic city at night as a helicopter zooms past. The title of the anime, BUBBLE GUM CRISIS, appears in bold, capitalized red letters, as the helicopter zooms. A brief panning shot of a street slowly transitions into daytime where a low-rise cityscape appears.

Here, a montage of luxury retailers, chrome-studded buildings, and a crowd of women working out, contrasting the scene in an underbelly of a city, where vagrants sleep on the sidewalk and a busted-up bus on the road. It pans up to show a truck with a pink graffiti of “PRISS”, where inside a woman with 80s hair polishes a red motorbike.

Next, a seedy part of the city at night transitions into a dark, dingy alley, leading to the entrance of a nightclub with a pink neon signboard with vagrants trying to eke sleep. “Hot Legs” was the name of the nightclub, as 80s-style song plays, just as a poster for an anime band “Priss and the Replicants” appears. A musical clip played as the lead sing got ready for the stage and sung the song with the English-translated lyrics, presented in a karaoke style.

Kenny enjoyed listening to the Japanese-language song, now able to understand what the lyrics were using the subtitles. He karaoke’d to the song as he held an air microphone in his hand, while he read the subtitles and watched the animation on his own. Although the subtitles were of a poor quality, prone to bad synchronization and faded lettering, this never stopped him from taking pleasure reading it.

Afterwards, he took the Bubblegum Crisis videocassette home to show it to Erwin. Watching it together, the 45-minute anime film was awe-inspiring and electrifying with its visuals and story. The animation was similar in style with Robotech, except it was much fluid and less chalky-looking. It integrated visual elements from Blade Runner, The Terminator, and Streets of Fire – gritty background, neon colors, and a dose of sci-fi action.

Erwin, slightly showing off his perverted side, complimented shapely, voluptuous appearance of the Knight Sabers while Kenny admired the mechanical designs of the Knight Sabers. They considered the anime to be the closest spiritual adaptation of AKIRA, mainly their idea of the anime adaptation. Plus, the music was so good that they wanted the soundtrack cassette of their own.

Kenny and Erwin hungered for more anime. The fansub of Bubblegum Crisis, Harmony Gold’s dub of Robotech, the Eclipse Comics manga, the Epic Comics edition of AKIRA, Warriors of the Wind, and the miscellaneous unsubtitled anime were not sufficient for their interest. They wanted more of it. It was a primal urge that they could no longer put on its leash. They needed a way to find more. But reality kicked in, as their current financial situation, the hardware limitations of their computers, and related matters prevented from satiating that urge. Ultimately, when there’s a will, there’s a way for the two to get their anime fix and prop up the Cartoon/Fantasy Organization, Torrance chapter.

The film’s dialogue was recorded from the sessions of the voice actor cast, aided with animatics depicting the events of the film, before production of the animation even began. This practice was unprecedented for its time, as voice acting sessions only began when the animation was complete. It took more than 160,000 cels to animate the uniquely fluid style of the film at the Tokyo Movie Shinsha anime studio. The animation was further augmented with the integration of computer-generated imagery, produced by High-Tech Lab Japan Inc. alongside Sumisho Electronic Systems Inc. and Wavefront Technologies.

Promotion for AKIRA was pervasive, lavishly-budgeted, and extensively-hyped all across Japan. Nearly every anime magazine in the country reported on the production of the film, as well putting up print advertisements on their pages. Television spots depicting short clips from the films aired on Japanese networks.

In total, the budget for the film cost 1.1 billion yen during its production and marketing. Experts predicted the film would be the highest-grossing film in Japan, with the assumption there was little interests from international audiences. Upon the film’s release, it became the sixth highest-grossing film. Despite the apparent claim, it barely recouped its budget of 1.1 billion yen with a box office gross of 1.5 billion yen. To the producers and box office analysts, it was a gigantic failure alongside its fellow film, Royal Space Force: Wings of Honneamise by Studio Gainax. The failures of the two big-budgeted films left the anime industry in a gloomy, doubtful future.

In the United States, Toho attempted to strike a distribution deal with famous filmmakers, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, but it fell through badly. Spielberg and Lucas both said the film was unmarketable in the America, aware of the negative stigma attached to animation as ‘a medium fit for children’, combined with the potential R-rating of the film and state of animation films in the domestic box office. In other words, the box office prospects of AKIRA in the United States were forlorn and paltry.

Yet, there was light at the end of the tunnel – Streamline Pictures. A company headquartered in Los Angeles, California, and founded by Carl Macek, a former Harmony Gold employee who produced Robotech, and Jeremy Beck, an animation historian. It was to produce high-quality, uncut releases of anime for American markets with the music intact and an accurate English dub. They were aware of the tendency for licensors and distributors to heavily edit anime for kids, which often meant masterpieces like Hayao Miyazaki's Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind to be unrecognizably mangled.

Streamline Pictures licensed the film from Toho for an undisclosed sum. They subcontracted Electric Media, who dubbed the film in English under the direction of Sheldon Renan and Wally Burr. The script for the dubbed version was written by L. Michael Haller. The anime was a really difficult one to dub. Unlike many anime of its time, the lip flaps of the characters were animated according to the pre-recorded dialogue.

Hence, the dub script was written to accommodate the lip flaps of the characters and to avoid the issue of out-of-sync dialogue which commonly plagued English dubs of Chinese and Japanese films. The dub’s cast consisted of noted voice actor Cam Clarke, who voiced Leonardo and Rocksteady in the 1987 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles cartoon, and the rest were relative unknowns or workmen in the English voice acting industry.

Kenny Wu learned of the film’s existence as soon as he read the production insights section of Epic Comics’ translation of AKIRA. Alongside exchanges with the local anime and manga fan community as his source of information, he informed his friend, Erwin Mab, about the film. They were both amazed, as though their dreams have come true. An animated adaptation of the comic itself. They quickly went on a stakeout for any streams of information about the film. They read through the Japanese-language magazines. They started discussions with others in the fan community, trying to gather information as much as they can. They speculated on the content of the film, whether it would cut or keep the entire story at feature-length,

Finally, AKIRA arrived in American cinemas on 25th December, 1989. Kenny read a local newspaper to check for showtimes of movies he wanted to see. In the section where the local Torrance movie palace, AKIRA was one of the films listed Tango & Cash, and Steven Spielberg’s Always. It was the film’s premier, going to be played at midnight, a timeslot usually reserved for films with low commercial prospects and niche audiences – high-prestige art films, low-budget exploitation films, and foreign films. He quickly marked the showtime and informed Erwin about it.

Kenny and Erwin arrived at the local Torrance cinema that midnight. The theater was a downtown movie palace that had seen better days. It used to be an attraction for the Torrance, who would flock to see a big-budgeted, star-studded epic movie from Hollywood in its heydays. Now it was reduced to a shadow of its former self as a result of societal changes from the years – the takeover by television for cheap entertainment, white flight to the suburbs, urban decay from the lack of tax income, high crime rate in the 1970s, and the loss of confidence from major studios.

It was such an eerie experience driving out in Torrance at late night, knowing that drunks, streetwalkers, and other creatures of the night emerged from their dens. Despite the initial fear, they were determined to watch AKIRA by any means necessary. In the hall where the film was played, it was packed with anime and manga fans alongside a smaller subset of bums, raincoaters, and gorehounds attending the premiere. The inside of the hall was seedy and worn-down, as if age and neglect took its toll on the once-beautiful interior. Nevertheless, it did not detract from the viewing experience, one that was exotic and exciting at the same time.

AKIRA began.

The film was captivating from the start. The opening scene of the Tokyo fireball which kicks off the events of the film to the biker gang fight between the Capsules and the Clown gang to the memorably signature scene of Kaneda sliding his big red motorbike on the street was nothing short but a miracle of awesome animation, all within the few minutes. The eyes of Kenny and Erwin, alongside everyone else interested in the film, glowed with such amazement and wonder, that they thought the film were a live-action film.

After the first opening minutes of the film, the main events of the film played out. The dialogue of the characters was oddly-pronounced and sounded older than their apparent ages, eliciting laughter and chuckles from the audience. The way the main character’s name, Kaneda, was pronounced similarly to the country, Canada. Erwin often riffed on that aspect by adding “Eh,” or “boot/boat that”, every time this name was said by the characters in the film. Yet, the film’s fluid, great animation overcame the initial mockery of the English dub alongside its enthralling, if slightly disjointed story, with scenes lifting manga panels.

At the climax of the film, the entire audience was startled by the sight of Tetsuo, the delinquent kid with a grungy hairstyle, rapidly mutating into a grotesque being as every detail of his mutated body slowly morphed. One audience member screamed loudly upon seeing the viscous, fleshy, and fungous appearance of Tetsuo’s arms. In contrast, Kenny and Erwin loudly cheered at the scene as the intense sound engulfed the hall.

The film ended with the titular character’s awakening leading to an explosion that destroys Neo-Tokyo and Tetsuo recreating the world. It was a wild, exciting, and vivid ride to see. To the audience members, it was like watching Blade Runner and 2001: A Space Odyssey with elements of grindhouse thrills on a cocktail of LSD and XTC. After leaving the theater, Kenny and Erwin were jumpy, still jolted by the experience of watching the premiere of Akira for the first time in their lives. It was their defining moment in their young adult lives, to see a masterpiece of anime.

As they approached the car, the only thing Erwin blurted was: “That was totally awesome!”

The transferal necessitated Kenny and Erwin to pack up all their stuff and properties associated with the Torrance chapter of Cartoon/Fantasy Organization, so it would be moved to their dormitory at the university’s campus housing. Fortunately, they were the only occupants of the dorm, so nobody objected to their choice of decoration and cluttering the whole room with anime and manga paraphernalia.

The dorm next door belonged to Kenny’s senior in management, Jennifer Smith. Unlike them, Jennifer was studying for her Bachelor of Business Administration. As a result, she studied at a separate class than Erwin and Kenny. She was extremely studious and aloof, only caring for her appearance and her academics. Her only source of interaction was her circle of friends, who were studying other subjects for their degrees. She would hang out with them at the library or any quiet, secluded place.

Initially, Kenny did not show any interest with Jennifer, only seeing her as a fellow upperclassman and a neighbor in the student dormitory. He was really shy and awkward when it comes to talking to girls, as well dating them. Erwin’s persuaded him to talk to her, suggesting he should start speaking to her in hopes of sparking a relationship with her and grow into an assertive guy.

The first few times Kenny tried to speak to Jennifer, it was utterly disastrous in terms of interpersonal relationships. He flubbed when he tried to converse with her, stammering nervously and speaking with an awkward way of pronunciation as he blushed and shuddered. This was followed by him fleeing away from her just as he managed to speak for a few lines, leaving her flabbergasted.

In the meantime, the C/FO fanclub started to garner traction and drew students in. Shortly after Erwin posted the club advertisement on the student bulletin board, he soon received a list of applicants, mainly students who were interested in sci-fi and fantasy as well others who wanted to occupy their time with socialization and hobbies. He handed application forms, hastily made using a spirit duplicator at home, to the prospective members of the fanclub.

At the same time, Kenny entered the informal world of fansubbing and tape-trading. He clearly intended to acquire anime in subtitled form ever since he was gifted a fansubbed copy of Bubblegum Crisis in 1988. He was aware that his acquaintance, the proprietor of the local comic book store, was part of the tape-trading community. So he asked the proprietor about the tips and the tricks of the trade.

Procuring fansubbed copies of anime was an extremely time-consuming and painstaking process. The first step was to order an anime from the mailing list of a fanclub. Next, a blank tape was mailed to the fanclub in a return envelope with the address of the sender alongside the request. The fanclubs handed over the task of copying fansubs to a distribution group, who would then work on the fansubbing the anime.

The distribution groups acquired anime by any means necessary, whether by hook or by crook. They would either exchange recorded television episodes or B-movies with American military personnel stationed in Japan, who wanted English-language shows. In reciprocation, these military personnel would send in recorded copies of anime to the distribution groups. The availability of anime depended on the type of medium. Self-contained anime films, or Original Video Animations (OVAs) were easier to obtain than recorded television episodes because it was released direct-to-video rather than the whims of broadcast schedules. Another method of obtaining was to fetch recorded taped-off-the-air anime from grocery stores in Japanese enclaves in certain parts of North America.

The distribution groups preferred Laserdiscs over videocassettes. The audio and visual quality of the Laserdiscs was better than videocassettes, and less prone to errors or freezing. But videocassettes were ultimately more common and standard, as Laserdiscs were expensive to purchase and difficult to copy using consumer-level computers. Additionally, people in the states have more VCRs than Laserdisc players.

The distribution groups began working on the subtitling of the raw anime. The main program used to subtitle the master copies of the anime was JACOsub for the Amiga computers. They employed bilingual translators to translate Japanese audio into English subtitles, and then typesetted into the video. Afterwards, they used a daisy-chained VCRs to duplicate the master copy’s video onto high-end blank videocassettes for austerity. This was to avoid the issue of backlogs and people sending in poor-quality, blank tapes which would cause VCRs to jam.

After the subtitling process was done, the distribution group labeled and packaged the copies. They sent the fansubbed copy of an anime to the fanclubs, who in turn, send the copy to the sender who ordered it. It was a process that took weeks, sometimes months to complete. But it was better than the older method of distribution, which often left videocassettes jamming VCRs during the duplication process.

Kenny was lucky to obtain his first tape within a week. It was a copy of the first two episodes of Ranma ½ on videocassette. The audio and video quality was good, yet the yellow subtitles were unsightly and eyesore to read. It was from a local tape-trader named ‘Steven’, who collected episodes of Star Trek and sold tabletop games. Nevertheless, he brought it home to the UCLA’s C/FO fanclub.

As the C/FO fanclub continued to burgeon into a small-yet-influential club at the university, Kenny encouraged everyone to send in their fansubbed copies while he and Erwin ran the club. Every weeknight, they would host screenings of fansubbed anime at Erwin’s house on the television. It was a memorable experience, with fans trying to read the subtitles, or fighting over who gets to see first, and the snacks too. The stench of soda, hot dogs, and chips permeated the living room. On other nights, they would discuss about fansubs and try to decipher Japanese-language magazines. Sporadically, Kenny would obtain a copy of Protoculture Addicts and Animag for the others to read.

Sadly, like all the good things, they do not last long, and ultimately must come to an end. Members slowly began infrequently appear in the C/FO meetings and eventually leave it in order to focus on their studies and their coursework as well prepare for the final examination. So too did Kenny and Erwin, who sporadically hosted meetings and eventually disbanded the C/FO in order to concentrate on their coursework. Kenny felt wistful over parting ways with others. He fondly remembered the short-lived, yet momentous and joyful times in getting others interested in a niche hobby. He regretted never going to speak with Jennifer Smith, his upperclassman and seniro, and go out for a date.

In 1991, Kenny Wu and Erwin Mab graduated from University of California, Los Angeles with a Bachelor of Software Engineering. They were both 21 at the time upon leaving university to engage in job-seeking. Liberty International Components Inc., a distributor of passive electronic components based in Stanton, California, scouted the two with job offers. Without further ado, Kenny and Erwin filled in the job applications along with their portfolio and qualifications from studying at institutes of higher education. They were immediately employed at the company as interns.

[1] Yes, Warriors of the Wind was an actual movie. It was an English-localized version of Hayao Miyazaki's 1984 anime film, Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind. Tokuma Shoten sold the foreign distribution rights to World Film Corporation, who later transferred it to Mason Corporation, who commissioned an English dub. The dub script was rewritten by David Schmoeller (who's better renowned for directing Puppet Master, released by Full Moon Features) and was heavily edited for release as a kid's film that ripped off the sci-fi adventure films at the time. Needless to say, Hayao Miyazaki hated the version to the point of having a policy of "No Cuts" at Studio Ghibli ever since.

[2] These are Fang of the Sun Dougram, Crusher Joe, and Super Dimension Fortress Macross, a trio of science fiction anime that provided the illustrations for the designs of the Battlemechs in Battletech. The use of Macross designs provoked a lawsuit by Harmony Gold and Playmates Toys on FASA for copyright infringement in 1996, leading FASA to phase out Battlemechs using the anime-derived illustrations and hence referred to as the "Unseen".

[3] Eclipse Comics, a publisher which first published graphic novels for the direct market and the first proponent of creator-owned comics and its royalties, was the first publisher to release manga in English, licensed from Shogakukan mana - Area 88, Mai, the Psychic Girl, and The Legend of Kamui with the help of Viz Comics. Before Eclipse Comics could release Urusei Yatsura (dubbed Lum: Urusei Yatsura), Viz Comics terminated its partnership with the company, leaving Studio Proteus as its main licensor. Eclipse was also the publisher for the American version of Dirty Pair, the first OEL (Original English-language) manga.

[4] A colorized, flipped version of AKIRA by Katsuhiro Otomo actually existed. It was heavily modified to suit the format of American comics at the time, as manga was relatively unknown aside from Eclipse Comics' release of three manga licensed from Shogakukan. The changes itself was approved by the author himself. The coloring was done by Steve Oliff, who received three consecutive Harvey Awards and the first Eisner Award for his efforts in colorizing the manga. Sadly, that version of AKIRA is long out-of-print and has not been collected properly.

References:

Megatech Software was the first licensor of ‘eroge’, or video games with erotic content depicted in anime-style illustrations. The company was apparently founded prior to 1992 by Kenny Wu, in Torrance, California. The company prided itself as being the only licensor and distributor of ‘anime games’ in the United States. They advertised their games on the lurid, thrilling elements coupled with anime-style graphics during a time where Japanese animation was considered a niche interest only found in the science fiction/comics fandom, and where the video game industry in the West were adverse to the inclusion of nudity and sexuality in video games.

The company only released four games in total – Cobra Mission, Metal & Lace: Battle of the Robo Babes, Knights of Xentar, and Power Dolls. The first three games were self-rated with the in-house content rating system whereas the last game was released without any labels. They promoted two of their new games at Anime Expo 1993. Megatech Software quietly folded sometime in between 1996 to 1999, following the release of their last game, Power Dolls.

Aside from the company, there were other companies who tried to license and localize ‘anime games’ or eroge for Western markets - the UK-based Otaku Publishing, Himeya Soft, Mixx Entertainment, Samourai, and JAST USA. Out of the six companies, only JAST USA managed to thrive until modern times while the rest were forgotten into the depths of obscurity.

In conclusion, Megatech Software, alongside the obscure, ephemeral companies, represented a brief, forgotten period in anime fandom history where they tried to capitalize on the burgeoning curiosity of anime during the nineties boom as well attempt to localize eroge and bishoujo games for Western audiences. The ‘anime games’, the screenshots, and a few pieces of memorabilia will be the only thing left of its period.

My journey of writing the timeline Let Megatech Satisfy Your Most Primal Desires, alongside the rabbit hole of ‘anime games’ of the 90s and early anime fandom, started when I read an article for Cobra Mission on Wikipedia. It was something of an eye-opener as I never knew eroge, let alone anime-style video games, existed, and certain companies in the West decided to localize these games for English-speaking markets. Since then, I worked on the timeline for nearly a year from the first post. Days of research and drafting for the entries, using available material from old websites archived on the Wayback Machine, specialized blogs, and other sources whenever accessible.

The previous version of the timeline, originally published in 2023, was interesting in its first few entries, but eventually lost steam with only between two or three readers interested in it. Additionally, I began noticing up weaknesses in my writing as I further developed my skills along the way, such as lengthy, banal conversations, and odd emphasis on formal names. I realized the prose was not up to my standards, and thus I became dissatisfied with the quality.

Because of this, I am going to write a new and improved revision of the timeline. After some lengthy deliberation whether I should make its own thread or just replace chapters with revised ones in the old thread, I ultimately went for making its own timeline. I hope the moderators understand I am not making a duplicate timeline, rather a new, self-contained timeline thoroughly distanced from the original timeline.

Shout out to @Nivek, @WotanArgead, @Otakuninja2006, and the others who supported the previous iteration of the timeline. I could not have gone so far with writing it without your feedback and discussions. But for now, let’s get into this new timeline and see where it goes.

Disclaimer:

The timeline is a work of fiction.

Unless otherwise indicated, all the characters, names, business, events, incidents and other references, depicted or mentioned are either products of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblances to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, are purely coincidental. The author does not endorse products or viewpoints presented in the narrative.

The following work contains depictions of offensive language and some suggestive language.

Reader discretion is advised.

--#--

"I thought Megatech Software would only last five years. It started out as just a subsidiary for Liberty Components International to deduct some taxes by capitalizing on the 90s anime boom. Look here now. We're the largest and influential licensors of anime games in America. For a company just founded by a geeky college graduate specializing in niche video games, it's astounding. I'd like to thank everyone for the journey. I'll say an old tagline of ours to conclude the interview: Let Megatech Satisfy Your Most Primal Desires!"

-- Kenny Wu on Megatech Software. Quoted from Preface, An Unabridged History of Anime Games (2023) by Cynthia Wu and Hannah Everheart

"I thought Megatech Software would only last five years. It started out as just a subsidiary for Liberty Components International to deduct some taxes by capitalizing on the 90s anime boom. Look here now. We're the largest and influential licensors of anime games in America. For a company just founded by a geeky college graduate specializing in niche video games, it's astounding. I'd like to thank everyone for the journey. I'll say an old tagline of ours to conclude the interview: Let Megatech Satisfy Your Most Primal Desires!"

-- Kenny Wu on Megatech Software. Quoted from Preface, An Unabridged History of Anime Games (2023) by Cynthia Wu and Hannah Everheart

Prelude

1985.Kenny Wu thrashed and turned in his sleep, tucked under the blanket as he lay on the bed. He rose out of the bed suddenly, yet slowly, because he felt his manly parts straighten and tighten. He shifted off his blanket and left his bed into the dark room. The sound of a relentless downpour drummed from outside the window. The electronic clock on the bedside indicated it was early in the morning. He yawned as he headed towards the bathroom. The corridors were dark, yet he navigated effortlessly since the layout was extremely familiar to him. He turned on the light once he was inside, yawning heavily as he glanced at the mirror. He saw his reflection – a youthful, slightly gaunt Chinese-American teenager with scruffy black hair.

He awkwardly smiled as he turned around to face the toilet, which he relieved himself from the discomfort. He stretched himself, looking into the mirror. He once joked to his friends at a Torrance high school that he was the grandson of Bruce Lee and he couldn’t wait to get a body like him. Unable to find himself a way to sleep properly as well still feeling the waning sensations of his discomfort, he went into the living room. He sat down on the couch, sitting in the dark room with only the heavy rain being the ambiance. He disliked the heavy rain, being very noisy and distracting for someone who was trying to sleep.

He fumbled in the dark to find the on switch for the television. Under the television set were the Nintendo Entertainment System and the Sony videocassette player, two pieces of electronic entertainment for the television. He wanted to see something that would lull him to sleep, like an obscure, regional public access show or a dull infomercial.

Soon, the television turned on just as Kenny lied on the couch trying to catch the need for sleep. The screen showed a blank space background, accompanied by a stirring arrangement of orchestral instruments. He was jolted awake by the intro, quickly affixing his gaze on the screen. A sepia-tinted filmstrip, cut and slightly burnt at the end, crawled up the background, which said strip depicted a spiral galaxy.