Hello everyone! I know it's "just a bit" since the last update, but with the world collapsing in flames around us I haven't had a good chance to do a lot of writing. However, I got the next update finally finished and since the plant I work at is shut down as the workforce is suffering a newsworthy outbreak of the 'rona, I should have more free time. Anywho here we go.

There is nothing which I dread so much as a division of the republic into two great parties, each arranged under its leader, and concerting measures in opposition to each other. This, in my humble apprehension, is to be dreaded as the greatest political evil under our Constitution.

--John Adams, 1789

Foundation of the Second Party System from ITTS:usa.was.americanhistory.gov, 2042

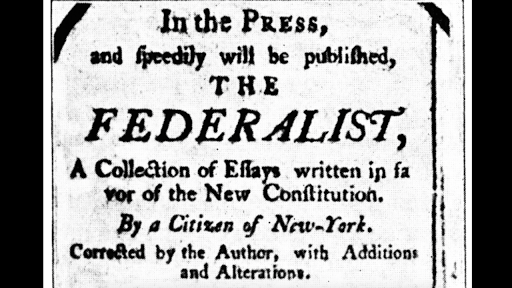

The 1798 congressional elections proved critical for both the Republican and Federalist Parties as tensions between intra-party factions were flaring. The Republican Party was torn between the “Democratic” faction which pushed for a more limited federal government, the “Federal” faction which pushed for a stronger federal government, and a small but vocal “Radical” faction which demanded a republican restoration at any cost. Similarly, the Federalists were splitting as the de facto head of the party, Alexander Hamilton and his “High Federalist” clique were leading the party down a pro-monarchical path which caused those more neutral on the issue to grow increasingly resistant.

The results of the election were somewhat unsurprising as the Republicans kept the majority in the House of Representatives albeit with thinner margin than before as independents and Federalists took several new seats. A number of American citizens shifted against the Republicans due to Clark Hopswood’s attempted return and the slowly emerging New Legion led to some who were on the fence on the monarchy shifting against the Republicans. This shift highlighted the tensions within the parties as many of the new voters who voted for the Federalists were neutral towards the monarchy or even slightly republican which stood at odds with the Hamiltonian clique. For the Republican Party, the intra-party division between the pro-British Federal faction and pro-French Democratic faction intensified due to the election, while the de facto leader of the Radial Faction, North Carolinian Senator Timothy Bloodworth, [1] drove the wedge between the Radicals and the rest of the republican movement even deeper by openly referring to Princeps Gilbert as a traitor, tyrant and “papal slave” on the Senate floor.

While the divisions between the Republicans were patched over by the common belief in republicanism, the Federalist Party had no such unifying force. Senator Charles Pinckney would lead the breakup of the Federalist Party, working with four other members of Congress to form a new party: the National Party on September 12, 1798. The National party was supportive of a stronger Federal government but with a “wait and see” attitude towards the monarchy. This neutrality made the National Party a perpetually popular party in United Statesian politics of the era; starting in 1800, the National Party would remain in the governing coalition for three decades even as other parties came and went. The National Party would ultimately be forcefully merged with the Liberty Party in 1844 by Conductor James Polk...

As many Federalists were neutral on the monarchy or even leaned slightly republican, the Federalist Party suffered a number of defections to the National Party. By the 1802 elections, the Federalist Party had lost many members who were ardent supporters of Federal power with many who replaced them being more pro-monarchy than proponents of Federal power. Only Alexander Hamilton and a select few holdouts’ strong nationalism which maintained the pro-Federal power stance of the party after 1810 as the Federalist party withered to only about half a dozen Congressmen at any given time. After Hamilton finally resigned from politics in 1824, the long-in-decline Federalist Party would abandon its pretensions of being anything other than a pro-Monarchy party and change into the Imperial Unity Party which would in turn maintain a minor but vigorous existence until being one of the five parties involved in the formation of the Pan-American Nikist Party in 1925.

While the breakup of the Federalist Party should have given the Republican Party a massive leg up, it did the exact opposite. Tensions between the Democratic and Federal factions only rose as the need to maintain party unity decreased with the collapse in unity in the opposition. Additionally as the pro-monarchy bloc shrunk, the Radicals began to fight any political action which wasn’t explicitly geared towards reestablishing a republic. Radical Republican Senator Bloodworth would go so far as to end every one of his speeches with “Ceterum censeo Regno esse delendam,”

furthermore, in my opinion, the Kingdom must be destroyed. [2] By 1799, the factions were openly quarreling with each other, leading to the Republican Party breaking up as Director Jefferson led the Democratic faction to establish a new political party, the Democratic-Republican Party on May 9th. The Democratic-Republican Party was a states rights, pro-farmers and planters, and moderate republican party. Being led by the popular Director of the State Thomas Jefferson, and being the only party that embraced a pro-state power stance, the Democratic-Republican Party quickly became the largest party in both the House of Representatives and the Senate although the Democratic-Republicans would never achieve a majority in either branch of Congress. Much like Director Jefferson, the Democratic-Republican Party was fairly francophilic, although in contrast to Director Jefferson who viewed the early French Republic positively, the majority of the Democratic-Republicans publicly argued for the exiled Bourbons with favor and rallied against Jacobinism and the corrupt Directory. How much of this was just political rhetoric however is frequently debated by historians as many Democratic-Republicans were known to be critics of the Bourbons in private, and the Franco-American War made public support for the French Republic near political suicide...

The Federal faction, led by Director of the State John Adams, would establish the Liberty Party on May 16th both in response to the Democratic Party’s establishment and to leave behind the increasingly politically toxic Radicals. The Liberty Party was broadly pro-federal power, although less so than the National Party, as well as additionally being a moderate republican party. While Director Jefferson would write privately that he dreamed of a future where the United States was a sprawling republic of self-sufficient yeoman farmers, Director Adams would publicly and explicitly lay out the Libertyite plan for a future Republic of the United States. Adams envisioned “a government strong enough to defend the liberties so that a Republic could be maintained,” rhetoric which flowed against even that used by the Nationalists. Furthermore, the Libertyites would argue that the idea that a successful Republican government was one that was “so weak as to be unable to take away the liberties of the people'' was what had led to the First Constitution failing in the first place. According to Libertyite rhetoric such a republic, if it were established again, would inevitably lead to a repeat of the crises of the First Constitution that would lead to a despotic Monarchy the next time around. The current government had only avoided ending in Monarchist tyranny because, as the Libertyites put it, Princeps Gilbert was “of a totally unique nature which mankind has not otherwise seen nor shall be seen again.” The fall of the French Directory and Napoleon Bonaparte’s rise to Emperorship in France was often drawn upon by Libertyites as a glimpse of the future of a Second Republic if the Libertyite plans for a Republican government were ignored. Curiously however, even as the Liberty Party argued for a Second Republic, the Libertyites would begin to reconcile with the monarchy after Director Adams’ term ran out in 1802. Libertyite Senator James Madison took charge of the party after Adams, and his eclectic views on republicanism would somewhat reshape the Liberty Party.

After the murder of his father and brother in 1800 by New Legionaires, Madison engaged in a slightly bizarre period of revision and “correction” of his pro-republican writings, driven by guilt for some perceived connection between Madison’s writings and the murders. [3] In truth, the New Legionaires had just mistaken his father, James Madison Sr. for Senator Madison whom they had intended to murder for being an architect of the Second Constitution. During this period, Madison seems to have reconciled his republican beliefs to support the Princepate by concluding that the United States was already a republic as republicanism was truly about principles, not the superficial titles that were used. Madison would refer to this as the government of the United States being a “sheep in wolf’s clothing,” arguing that while the country seemed to be a monarchy which was “inherently tyrannical” that it was merely a harmless republican state instead. This interpretation of the situation was never truly accepted by most republicans and was controversial even within the ranks of the Libertyites, but Madison’s arguments would see the beginning of a shift in the Liberty Party that would eventually see the party not only accept the monarchical government but openly support it under the Polk and Walker dictatorships...

...even as the political parties continued to fragment, the need for a unified government grew. The Raid on Pointe-à-Pitre triggered a political crisis in Franco-US relations, culminating in then Consul Napoleon’s decision to issue his 1800 Declaration of War upon the United States to “sweep away the Marquis’ upstarts” and secure his ambitions for a North American colonial empire. Initially the official state of war changed little as the fighting continued to just be a string of naval skirmishes as Great Britain’s far larger navy and fighting in Europe kept France too busy to fight the United States. Without a significant threat from France, no unity came in response to the War and domestic political issues prevented decisive action during the initial period of the war. Director Jefferson would win the only re-election of a Director of the State by the narrowest of margins thanks to a series of backroom deals, and Colonel Henry Dearborn would win the Director of the People election in 1802 as a Democratic-Republican. However, shifting political winds meant that while the Democratic-Republicans continued to maintain a plurality, the Liberty and National Parties could form an alliance to achieve a majority, deadlocking the government even as the Treaty of Amiens meant that the United States was now forced to fight France with only the Haitian rebels as cobelligents...

An Empire of Republics: The States Before Polk by Isaac Carter, 2024

When the Second Constitution was adopted, it permitted each state to adopt a form of government so long as it was “representative.” For the first few years the states simply maintained the titles they had under the First Constitution, however on September 6th, 1793, Connecticut changed its official name from the “State of Connecticut” to the “Republic of Connecticut.” In response, the government would pass a law that forbade any state from having a republican government. While Gilbert I would attempt to veto the law, citing the rights of the states, Directors Aaron Burr and John Rutledge would override his veto.

In response to the law, Lieutenant Governor of Connecticut, Oliver Wolcott, would sue the Federal government over the issue and after a two-year legal battle in the case Wolcott vs. United States, the US Supreme Court determined that the States had a constitutional right to establish republican governments. With Wolcott’s victory, six other states: Georgia, Cumberland, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire would declare themselves to be republics as well. Pennsylvania would also declare their state a republic without changing the title from Commonwealth. Until the reorganization of the state governments by the Third Constitution, the USA would see the admission of seven additional republics, and the abolishment of the Georgian and New Hampshirite republics.

With the exception of New York which declared itself to be a “neutral” state, other states would officially establish ”monarchical” governments although only South Carolina would establish an actual noble position which was anything other than symbolic; the Duke of South Carolina would have a limited veto. The remainder of the monarchical states were what was referred to by later accounts as “Regent Republics,” or monarchical governments with an elected position assuming all executive functions. The term Regent Republic comes from the structure of the Commonwealth of Virginia which created the title of “Duke of Virginia,” however an elected Regent served in the position until the Virginian government was reorganized by the Third Constitution. While the term would be expanded to refer to all of the US states which didn’t actually put a noble into office, the term only accurately refers to Virginia and New Jersey’s structure of government…

...Under the 1791 Constitution, one of the few powers given to the Princeps was the right to grant noble titles “with the consent of those under the jurisdiction of the title,” and to revoke “harmful or abused” titles unilaterally. Curiously, this provision was the only mention of noble titles in the Second Constitution, likely an unintentional oversight by the drafters of the Second Constitution. With this power and the go-ahead by the newly elected Directors Adams and Jefferson, Princeps Gilbert would sponsor the creation of the College of American Titles and Arms in 1796 to oversee the granting of noble titles and coats of arms. Formally, the College had no powers beyond that which Princeps Gilbert possessed, however most states would eventually agree to follow the College’s direction after the College arbitrated the “Title War,” a political dispute between the states when Virginia attempted to claim a status of being “First amongst Equals” and granted itself a higher ranked title of “Archduchy” to reflect these claims. Without any significant legal basis existing at the time by which the dispute could be answered, and with the risk that a fight in the courts would be expensive, unpopular and potentially entirely useless without a legal basis, the parties in the dispute agreed to allow the CATA to arbitrate the dispute. This decision led to the general acceptance of the CATA which would only be enshrined in actual law in 1821...

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

And finally, here's a list of US states with a little bit of info on their government structures. I've had GIMP eat two maps I've tried making for this info, so I'll add one when I finish.

Massachusetts, Republic of

Executive: Governor, elected popularly in yearly elections.

Legislature: Bicameral, Senate and House of Representatives

Special Considerations: In response to the Regulator Rebellion, the pre-existing District of Maine and a newly created District of Berkshire were granted special autonomous judiciaries.

New Hampshire, Republic of

Executive: President, elected popularly in yearly elections.

Legislature: Bicameral, Senate and House of Representatives

Special Considerations: none

Vermont, Republic of

Executive: President/Governor used interchangeably, elected popularly in yearly elections

Legislature: Unicameral, General Assembly

Special Considerations: none

New York, State of

Executive: Governor, elected popularly in yearly elections

Legislature: Bicameral, Senate and Assembly

Special Considerations: Due to harsh internal division over the Monarchy, New York is the only state which never adopted a status as a Republican or Monarchical state.

Connecticut, Republic of

Executive: Executive Council (1802 onwards), five officials elected by the Connecticut legislature

Legislature: Unicameral, House of Representatives (1802 onwards)

Special Considerations: The 1802 Constitution reformed the Connecticut government by establishing the Executive Council and abolishing the Senate.

Pennsylvania, Commonwealth of:

Executive: President of the Supreme Executive Council, elected by the Supreme Executive Council

Legislature: Unicameral, General Assembly. The Supreme Executive Council is sometimes considered a de facto upper house

Special Considerations: The President of the Supreme Executive Council was the only US official to officially be addressed with “his Excellency” by 1810.

New Jersey, Duchy of:

Executive: Regent, elected popularly every three years.

Legislature: Bicameral, the General Assembly and Legislative Council

Special Considerations: Neither branch of the legislature was apportioned by population, and the position of Duke was perpetually filled by constitutional obligation to be filled by an elected Regent instead of a Duke.

Federal District, no title

Executive: the Executives of the United States: Princeps/Emperor, Director of State and Director of People

Legislature: none, the US Congress serves as a de facto legislature for the territory.

Special Considerations: The Federal District is directly governed by the US Federal government and while some proposals to grant autonomous government to the district did exist, they were never ratified.

Delaware, Earldom of

Executive: Joint government of the Earl and President

Legislature: Unicameral, General Assembly appointed quasi-proportionally by population.

Special considerations: De Facto power never was held by a separate Earl as the position was always held by the President, not as a regency but as an actual filling of the office. The formal address for the executive of Delaware was “President and Earl of Delaware.”

Maryland, State of

Executive: Governor, elected yearly by the General Assembly

Legislature: Bicameral, House of Representatives and Senate

Special Considerations: A position of “Palatine Lord” of Maryland was created in the 1791 Constitution, however the position was never filled by either a regent or officeholder. The CATA would declare the title of Palatine Lord invalid in 1799 and although the government of Maryland was one of the few to reject cooperation with the CATA, the title went unused.

Virginia, Duchy of

Executive: Duke of Virginia, unelected

Legislature: Unicameral, House of Delegates

Special Considerations: The establishment of the Duchy of Virginia saw the dissolution of the 1776 Senate. In 1797 Virginia attempted to declare their government an Archduchy and claim that as the largest and most populous state, Virginia was the “preeminent” state in the Union, although this was rebuffed.The office of Duke was always filled by an elected Regent, never an actual office-holder and possessed no powers.

Kentucky, March Republic of

Executive: Governor, elected every two years

Legislature: Bicameral, House of Representatives and Senate

Special Considerations: The term March Republic was controversial upon its adoption, however as the March Republic continued, it was embraced as the Kentuckians saw it as a symbol of their states status as the “Shield of Civilization on the Frontier.”

North Carolina, State of

Executive: Governor, elected yearly

Legislature: Bicameral, House of Representatives and Senate

Special Considerations: Officially a monarchist state, no noble titles were ever created by North Carolina.

Cumberland, Free State of

Executive: President, elected every four years

Legislature: Bicameral, House of Representatives and Senate

Special Considerations: Cumberland was officially called the Free State of Tennessee, however unofficial parlance began to refer to the state as “Tennessee-Cumberland,” “East Tennessee” or just ‘Cumberland” as to differentiate between the US State of Tennessee and the Trekker Republic of Tennessee which was named after the state. The name would be changed in 1814 and the state is generally referred to Cumberland retroactively.

South Carolina, Duchy of

Executive: Duke of South Carolina, unelected

Legislature: Bicameral, General Assembly and Senate (1794 onwards)

Special Considerations: South Carolina was the only state to have an independant empowered noble position. The General Assembly was elected by qualified voters while all of the Senate was appointed by the General Assembly except for three Senators appointed by the Duke.

Georgia, Free Republic of

Executive: First Minister, elected by the Senate

Legislature: Unicameral, Senate of the Free Republic of Georgia

Special Considerations: In contrast to many of the other republics during this period, the Georgian Republic actually became more restrictive and embraced a form of quasi-arisocratic legalism to govern the state in an effort to disenfranchise the radical Waltonites who sought Georgian secession from the United States. In 1827, the Free Republic would trigger a political crisis when the Georgian Senate accidentally self-terminated.

[1] Bloodworth was a bit of a radical IOTL too, his letters to Jefferson are an interesting read.

[2] Despite having taken two years of Latin, I have no clue if this is a good rendition of the language. Apologies if I butchered it.

[3] IOTL Madison tried to rewrite his works, as well as personal correspondences at one point, I've just moved the cause around.