You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dreams of Liberty: A Failure at Princeton

- Thread starter ETGalaxy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 68 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

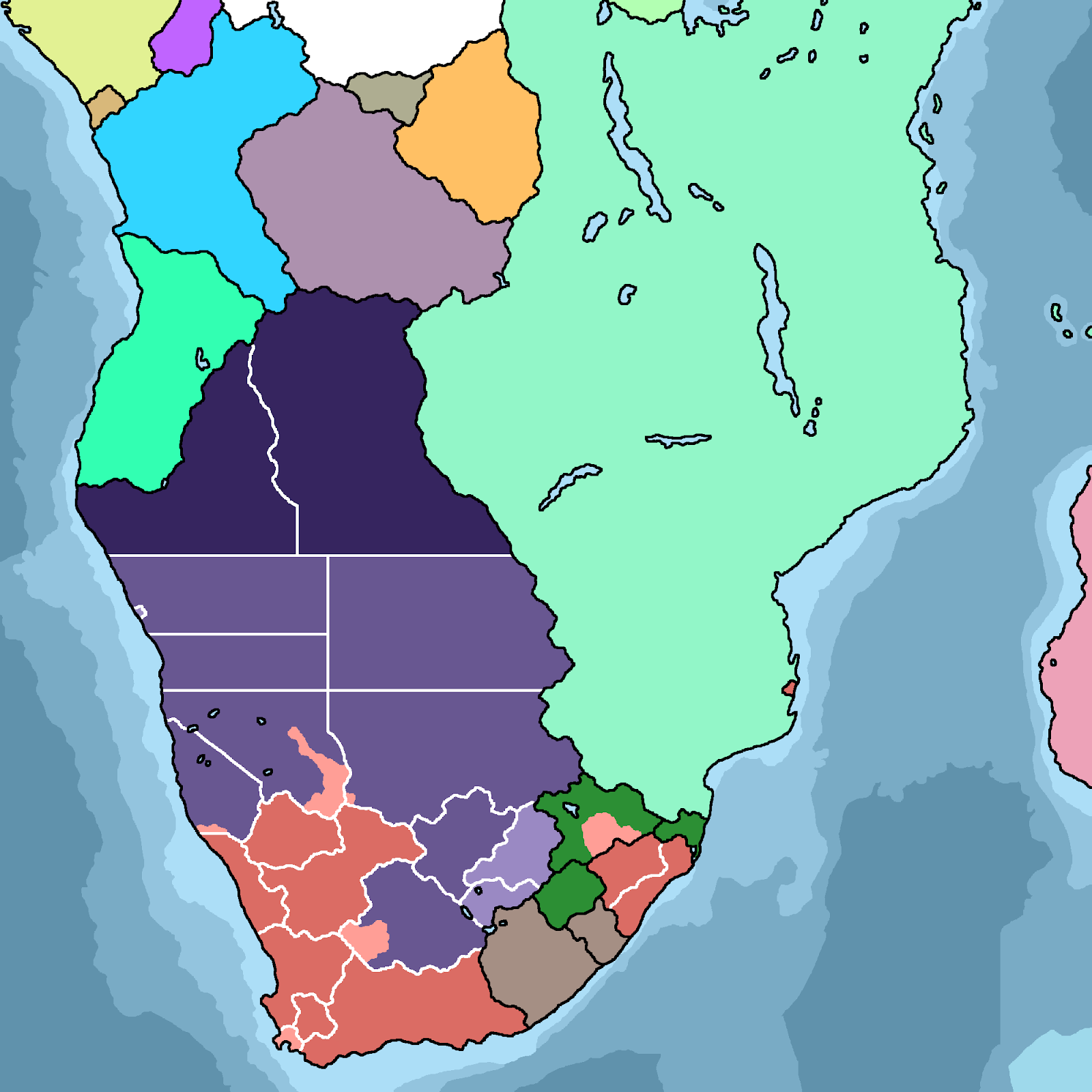

Jeremy Bentham Wiki Infobox Chapter Thirty-Two: A House Divided Map of the United Dominion of Riebeeckia Circa 1859 Riebeeckian chancellery election 1859 Chapter Thirty-Three: The Shot Heard Around the World United Dominion of Riebeeckia Wiki Infobox Chapter Thirty-Four: Revolution and Reaction Map of the Mutapa Empire Circa September 1860The focus for the next few chapters will be on the Equatorial Revolutionary War, so aside from Southeast Asia, none of those regions will be the focus of an update anytime soon. With that being said, however, I plan to hop over to Russia after I’m done with the ERW, so Scandinavia and Central Asia may get get some attention in that chapter.By any chance will there be an update on southeast Asia, Scandinavia and Oman, Yemen, Persia, and Central Asia?

There are some minor border changes (most notably, OTL Guatemala is a part of Mexico), but the borders will eventually change there. The Kingdom of New Granada isn’t done expanding its sphere of influence just yet.It's interesting that Mexico has the same shape as otl Mexico, will that change in the future?

Good question. Last time I shed some light on Jamaica, it was an independent republic formed via a slave revolt against Concordia. Since then, the country has been doing well for itself and is especially close to New Africa, however, the country remains highly agrarian and has yet to meaningfully industrialize.What happening in jamaica right now?

God damn it Breckinridge, even in this ATL you break stuff in the name of racial supremacy.

I'm surprised none of the protectorate kingdoms sided with Tuinstra, given how the north seems to hate the native africans.

How powerful is the southern navy? Without one, the north can never be reconquered. Speaking of which, how much industry does each side have?

I'm surprised none of the protectorate kingdoms sided with Tuinstra, given how the north seems to hate the native africans.

How powerful is the southern navy? Without one, the north can never be reconquered. Speaking of which, how much industry does each side have?

Even in a TL where they are born in a completely different country, some people never change.God damn it Breckinridge, even in this ATL you break stuff in the name of racial supremacy.

The main reasoning for this is that there is a significant factions of Revolutionary Burrites who support the abolition of the Native African absolute monarchies in favor of various replacement structures, be that provincehood, autonomous constitutional monarchies, or something else entirely, so aligning with Tuinstra is viewed as a potential risk by the protectorates with regards to maintaining their government structures. With that being said, all of the protectorates will have to sooner or later join a side in the Equatorial Revolutionary War, whether by choice or not.I'm surprised none of the protectorate kingdoms sided with Tuinstra, given how the north seems to hate the native africans.

In terms of naval strength, the south currently has the upper hand given that the provinces it has inherited are more industrialized and well established ports were significant naval forces are concentrated. The pro-Breckinridge territories with significant naval capacities are currently Austropolis, Edwardland, and New Hanover, and while this shouldn't be discounted, combined naval forces in Liberia, Zomerland, Indiana, Zululand, Fort Jaager, and even the Timor Territory give Tuinstra the advantage. As for industry, the disparity in terms of industry between the two sides is more or less comparable to the American Civil War, with the more developed and urbanized southern provinces being comparable to the Union and the more agrarian and sparsely populated northern provinces being comparable to the Confederacy, although it should be noted that both Edwardland and New Hanover have industrial capacities more comparable with the south.How powerful is the southern navy? Without one, the north can never be reconquered. Speaking of which, how much industry does each side have?

Because the Cape Colony is never annexed by the British ITTL, no, the Boers as we know them never existed. With that being said, the Dutch-descended residents of the Cape and later independent United Dominion of Riebeeckia are culturally very similar to the Boers of OTL, and a number of OTL leaders of the Boer republics are prominent politicians within Riebeeckia. I'd recommend reading chapters 17 and 18 if you're interested on what the people who would've been the Boers in OTL are up to ITTL.Question, did the Boers ever exist and if they did, did they rebel like in our timeline?

Deleted member 147978

For a moment, I thought this TL was dead, but alright then I'm happy that it's still alive.

Chapter Thirty-Three: The Shot Heard Around the World

Chapter Thirty-Three: The Shot Heard Around the World

“We’ll fight in the name of Father Burr, hurrah, hurrah!

We'll fight in the name of Father Burr, hurrah, hurrah!

Fight for Father Burr’s democracy, fight for the rights of you and me!

In the name of Father Burr!”

-Excerpt from “Fight in the Name of Father Burr”, a wartime song popularized in the United Provinces of Azania during the Equatorial Revolutionary War.

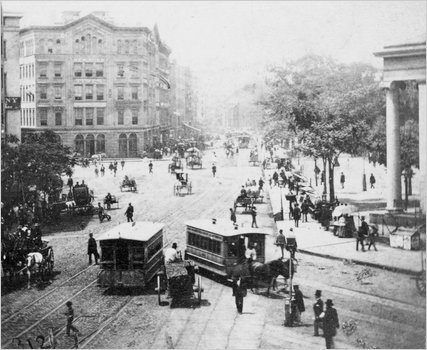

To this very day, it remains ambiguous who fired the very first shot at the Battle of Melkbosstrand. Regiments loyal to Hannibal Tuinstra insisted that they merely returned fire to men under Paul Kruger’s command out of self-defense, whereas regiments loyal to Samuel Breckinridge asserted that the more disorganized militias led by General Wilhelm Rosecrans got trigger-happy at the sight of their enemy approaching. Regardless of whoever fired the first shot, however, hundreds more followed from both sides of the frontlines drawn up at Melkbosstrand on September 28th, 1859, and as news of the first battle in Riebeeckia’s civil war frantically spread throughout the divided provinces of what had once been regarded as one of the most stable liberal democracies in the world at the time, hundreds of thousands more gunshots rang out between the two rival governments that had partitioned the Riebeeckian state, marking the beginning of one of the most important conflicts in modern human history. It was unbeknownst at the time, but within the coming years, the Riebeeckian Civil War would escalate into a vast regional conflict that was to give rise to a global superpower and in large part define the geopolitical dynamics of the upcoming 20th Century.

The Equatorial Revolutionary War had begun.

Paul Kruger’s easy victory at the Battle of Melkbosstrand was an immediate morale boost for the Crusaders of Riebeeckia, however, success for Breckinridge’s forces in the territory surrounding Austropolis soon proved to be short-lived. Encircled on all sides by provinces that had pledged their loyalty to Hannibal Tuinstra, it was seemingly inevitable that the Riebeeckian capital and largest city would sooner or later be pried from the hands of Breckinridge. The task of liberating Austropolis fell upon Otto Bismarck, the Iron General himself, who was initially appointed as Tuinstra’s Minister of War prior to the March on Austropolis and had subsequently been ordered to preside over a garrison of Tuinstra forces in southern Zomerland following the province’s recognition of Breckinridge’s regime as illegitimate in preparation for an offensive to retake what had been lost in the Crusaders of Riebeeckia’s putsch. Once news of the engagement at Melkbosstrand reached General Bismarck, Hannibal Tuinstra had given the go ahead to push into Austropolis.

Bismarck’s army arrived near the outskirts near midnight of September 28th. The Crusaders of Riebeeckia were well aware that the Battle of Austropolis was almost inevitably a lost cause, and Samuel Breckinridge would board a ship headed for Edwardston the subsequent afternoon to evade capture, however, pro-Breckinridge forces nonetheless held out to defend their control over a city that they had seized no more than two weeks earlier. Barricades were erected throughout the streets of Austropolis while Riebeeckian National Army armories scattered throughout the city provided the fighting force primarily consisting of reactionary militias with the equipment necessary to take on the trained and well-organized military regiments commanded by Otto Bismarck. The Battle of Austropolis therefore soon turned into a lengthy siege, with the goal of pro-Tuinstra forces becoming to encircle their enemy from all sides in order to gradually deplete its capability to effectively wage war. To accelerate the process, General Bismarck ordered the blockade of Austropolis from the sea, meaning that no reinforcements or supplies could enter the city’s ports, and oversaw aerial bombardment efforts by airships, which primarily targeted troop positions and enemy-held armories.

All of this is to say that the Battle of Austropolis was a very gruesome introduction to the Equatorial Revolutionary War. The center of Cape politics, commerce, and culture, even from before the formation of the United Dominion of Riebeeckia, was set ablaze by bombs and shot apart by organ guns. The sight of one of the world’s most pivotal trading hubs, once regarded as the heart of strong democracy, being transformed into a vicious warzone was harrowing to both domestic and foreign observers alike. To make matters worse, the two factions of the Riebeeckian Civil War had yet to differentiate themselves in terms of uniforms, symbolism, or even terminology, which meant that two forces calling themselves the Riebeeckian National Army were fighting each other under the same banners or uniforms, which understandably made the engagement logistically difficult and friendly fire commonplace. The belligerents gradually coalesced around hoisting the banners of their forces’ home provinces and bearing armbands of white and bright blue to represent combatants loyal to Breckinridge and Tuinstra respectively, however, chaos nonetheless persisted.

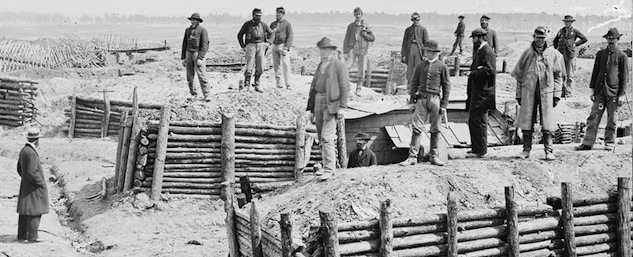

Ruins of the New Amsterdam borough of Austropolis, circa October 1859.

More so than the Battle Melkbosstrand, which was little more than a quick engagement at a mostly unknown town, the lengthy Battle of Austropolis was a harsh wakeup call to the cruel reality of the civil war that awaited all of Riebeeckia and the struggle for regional dominance that awaited the great powers of the Indian Ocean. Photographs of various landmarks, from Aaron Burr Memorial University to the Executive Mansion of the chancellery, being occupied by soldiers of both sides of the civil war circulated throughout the warring provinces, revealing to the Riebeeckian people that not even their grandest cities were free from the brutality of the newly-forged conflict. The Battle of Austropolis also inflicted a devastating, if not predictable, toll on the civilian residents of the capital city, who were stuck in the middle of brutal urban warfare. On top of the inherent destruction brought upon by industrialized warfare, the blockade and aerial bombardment of Austropolis harmed civilians about as much as pro-Breckinridge soldiers, and despite the city’s political progressivism, a handful of civilians grew to be spiteful of General Otto Bismarck and Hannibal Tuinstra’s government in large part thanks to the campaign.

Realizing that his campaign was having a negative impact on popular support for the Tuinstra government within Austropolis, Otto Bismarck utilized his position as the Minister of War to allocate provisional income and humanitarian aid to civilians left without a home as a consequence of the Battle of Austopolis. The aid provided by the program was limited, however, it nonetheless helped revitalize support for Tuinstra’s government amongst the people of Austropolis, which in turn caused General Bismarck to correspond with his chancellor, arguing that a program of social relief to those left without a home as a consequence of the Riebeeckian Civil War was necessary to appease civilians from both sides of the conflict and ensure long-term stability for whatever regime Tuinstra sought to construct in the aftermath of a hypothetical victory. Taking the advice of his Minister of War, Chancellor Hannibal Tuinstra would propose Reconstruction Insurance Act to his government’s makeshift Congress of South Africa, which had assembled in New Richmond in the immediate aftermath of the March on Austropolis, as a piece of legislation that was to establish a welfare program intended to guarantee housing to civilians that had lost their homes during the Riebeeckian Civil War and to provide subsidies to municipal governments in order to rebuild destroyed infrastructure. With the backing of the chancellor and the Revolutionary Burrite Party, the Reconstruction Insurance Act almost unanimously passed through the New Richmond Congress on October 10th, 1859, becoming the first building block of the welfare state that Hannibal Tuinstra was committed to constructing.

As congressmen debated welfare programs in New Richmond, Otto Bismarck’s push through Austropolis continued to advance towards total control of the city. General Paul Kruger was ordered to retreat from his northward offensive along the western coastline of Zomerland in order to focus on the defense of Austropolis, thus abandoning Melkbosstrand without a fight on October 4th, 1859. Naval and aerial forces under the command of pro-Breckinridge officers occasionally broke through Bismarck’s blockade to provide supplies, however, no reinforcements were provided to Kruger’s men given the simple fact that the Battle of Austropolis was a lost cause for the Crusaders of Riebeeckia, and by the time the Reconstruction Insurance Act was passed, the primary purpose of blockade runners was to evacuate pro-Breckinridge forces. Day after day, Bismarck’s army pushed deeper towards the heart of Austropolis, ultimately reaching Table Bay on October 15th and subsequently beginning the push towards the city center to the southwest, where the Executive Mansion, the House of Congress, and various other government buildings were located.

A sense of pride over holding onto the administrative center of the Riebeeckian government compelled General Paul Kruger to hold onto the Austropolis city center for as long as possible, however, his forces were already weary from days of warfare and rations were beginning to wear thin, not to mention that it was becoming increasingly difficult for his forces to be evacuated by blockade runners as the pro-Tuinstra grip on the waters and sky encircling Austropolis tightened. After two grueling days of combat, the city center fell completely into the hands of Otto Bismarck, who proudly toured the office of the Minister of War that he had resided in merely a month prior. Meanwhile, Paul Kruger finally recognized that there was no use wasting lives in the fight for Austropolis now that the city center had been wrestled away and thus led a rapid retreat towards Hout Bay in the south, one of the few areas still accessible to blockade runners, and evacuated the vast majority of his troops from the Ribeeckian capital by the time the sun had set on October 17th, 1859, the closing day of the Battle of Austropolis.

The Battle of Austropolis may have been a blatant defeat for pro-Breckinridge forces, however, the situation of the Riebeeckian Civil War on other frontlines was far from clearly in favor of one belligerent or another. The rapid dissolution of the United Dominion into warring factions had flung the entire national political structure into chaos, perhaps no more so than the armed forces. The bulk of military officers and regiments proclaimed their loyalty to the chancellor recognized by their home province, which both splintered the military chain of command and oftentimes left garrisons stationed in foreign provinces disillusioned with the regime they were ordered to fight for. Desertion was commonplace in the onset of the Riebeeckian Civil War as foot soldiers on both sides protested the makeshift governments commanding them. To make matters even more convoluted, the heavy involvement of militias in the civil war meant that both Riebeeckian Armies were fighting alongside what were effectively independent armed forces. The size and influence of the Crusaders of Riebeeckia in particular made for an awkward balance of power amongst forces fighting for Samuel Breckinridge.

For Breckinridge, the crisis of a disorganized military force was addressed by effectively integrating units of the Riebeeckian National Army loyal to him into the Crusaders of Riebeeckia, which was large enough to rival the size of a conventional military and already possessed a chain of command that had more or less unanimously aligned itself with Breckinridge, which meant that a reorganization of the paramilitary’s leadership was unnecessary. Chancellor Samuel Breckinridge would therefore use his position as the unquestioned leader of the National Cross Party to quickly pass the National Security Act, which adopted the Crusaders of Riebeeckia as the official ground force of his government and placed former forces of the Riebeeckian National Army under the control of the aforementioned Crusaders, on October 15th, 1859. Naval and aerial forces, which were not annexed by the Crusaders of Riebeeckia, remained relatively disorganized, however, Samuel Breckinridge would rebuild these military wings over time, and in the immediate onset of the Riebeeckian Civil War, the National Security Act gave Breckinridge an advantage, at least in terms of military organization.

Even while the Battle of Austropolis raged on, Edward J Jackson, Samuel Breckinridge’s Minister of War and the commanding officer of the Crusaders of Riebeeckia, began drafting plans for a general strategy of attack. Jackson ultimately determined that the best course of action was a rapid offensive, given that the predominantly agrarian provinces that forged the pro-Breckinridge government were more sparsely populated than those loyal to Tuinstra, and decided that dividing the pro-Tuinstra provinces in half via an offensive into Zomerland with the goal of capturing the coastal Victoria City was the best shot the Crusaders of Riebeeckia had at dealing a quick and crippling blow to pro-Tuinstra forces that would give the Crusaders the opportunity to no longer fight one large united front. Recognizing the economic importance of foreign trade to the southern provinces, Jackson also advised a blockade of the western coastline, hoping to shatter the Liberian and Zomerlander economies in particular. Simply put, Jackson sought to suffocate the pro-Tuinstra provinces as though his armed forces were a python snake encroaching upon its prey, hence why his strategy earned the nickname “Python Plan'' amongst the commanding officers of the Crusaders of Riebeeckia.

The Python Plan was launched from South Holland into Zomerland by General James John Floyd III, a prominent member of the Crusaders of Riebeeckia due to his tenure as a congressman from Binnenland, which made Floyd the few public officials of the national government to be an active member of the paramilitary (Floyd subsequently resigned from his seat in Congress upon being appointed a commanding officer of the Crusaders). This meant that James John Floyd III was a well-known and oftentimes deeply popular military officer amongst the general public, not to mention one with considerable political influence, however, he actually lacked any military experience despite having participated in Crusader training and often commanding the militia as a private security force. Edward J Jackson hoped that General Floyd would listen to his more experienced lower-ranking officers in the Zomerland Offensive, however, this soon proved to not be the case. Floyd’s advance into northeastern Zomerland was much slower than advised, and upon coming into contact with pro-Tuinstra forces at the town of Stinkkuil on October 20th, 1859, General Floyd’s immediate reaction was to set up entrenchments in order to deter an enemy counter-offensive.

The local pro-Tuinstra regiment had prepared for a quick and heavy offensive by the Crusaders of Riebeeckia, but Floyd’s concentration on developing trenches and barricades prevented this from being the case, which in turn allowed for pro-Tuinstra forces under the command of Wilhelm Rosecrans, having recently arrived from the Battle of Austropolis, to go on an offensive that, while ultimately more bloody for his soldiers than Floyd’s, nonetheless uprooted the Crusaders from Stinkkuil by the time the sun had set. Going on the retreat into the Karoo semi-desert, James John Floyd III ordered the construction of a long line of trenches to hold back Rosecrans’ army a few miles to the east of Stinkkuil, which ultimately prevented pro-Tuinstra forces from advancing for the time being as a war of attrition broke out and both sides dug trenches, however, the hope of a rapid offensive to Victoria City had been dashed thanks to Floyd’s incompetence, and Edward J Jackson began to recalculate the Python Plan as a strategy that could succeed in the relative long-term as opposed to remaining a quick offensive. As for Floyd, the general’s popularity prevented him from being removed from the chain of command, however, he was placed in control of the substantially less important Bloemfontein Front whereas the Karoo Front, and therefore ground operations of the Python Plan, were placed into the more capable hands of General Braxton Bragg.

Crusaders of Riebeeckia soldiers under the command of General Braxton Bragg inspecting a trench to the east of Stinkkuil, circa November 1859.

In Edwardsland, the offensive into northern Liberia was led by General Robrecht Young, a resident of northeastern Edwardsland who had converted to Calvinism in the early 1820s and spent much of his youth preaching the gospel throughout the predominantly Episcopalian Edwardsland and Liberia. Having gradually been drawn towards ideas of white supremacy and Christian nationalism, Young was attracted to the platform of the National Cross Party and ultimately winded up becoming an early general of the Crusaders of Riebeeckia, using his position to enforce the nullification of the Fourth Amendment in NCP-controlled provinces, violently expelling the indigenous Namaqua people of eastern Edwardsland out of their primarily pastoralist communities, and harassing Catholics and non-Christians as a means of intimidation. Young’s brutal militancy combined with his intense religiosity earned him the nickname the “Lion of the Lord '' amongst both followers and opponents, and his experience in paramilitary activities made him an apparent choice for the command of troops upon the outbreak of the Riebeeckian Civil War.

Once the United Dominion collapsed, Young was quickly appointed to command ground forces in the conflict against the ardently pro-Tuinstra and heavily populated Liberia. The Lion of the Lord began his southward campaign upon receiving news of the Battle of Melkbosstrand and managed to quickly overrun the less well-armed pro-Tuinstra regiments at the beginning of the Riebeeckian Civil War. General Young soon became an infamous figure amongst his opponents, who noted his brutal sieges that targeted poorly-defended supply lines and civilian infrastructure in order to reduce the enemy’s capability to wage war, the high civilian casualties of his Autumn Offensive, and the internment of non-white and non-Protestant citizens in makeshift prison camps alongside prisoners of war. The Lion hunted his prey with a harsh ferocity, and anyone who dared to not conform to the National Cross Party’s strict definition of the Riebeeckian national identity was designated as prey.

Robrecht Young’s Autumn Offensive was effective in inflicting heavy casualties, however, its territorial progress was short-lived. After raiding several border settlements, Young arrived at the mouth of the Orange River, which the large port city of Gariepsburgh had been constructed around. The Battle of Gariepsburgh would begin on October 2nd, 1859 as General Young laid siege to the northern boroughs of the city, utilizing fleets of airships to set Gariepsburgh ablaze in what is regarded as history’s first pyrobombardment campaign. Young’s campaign of raining fire down upon Gariepsburgh was brutal, however, the general’s goal was to rob pro-Tuinstra forces of a critical port city, and in this sense, pyrobombardment got the job done. The bulk of Young’s enemies were forced to evacuate a burning city for Gariepsburgh’s surviving boroughs to the south of the Orange River, and those that did remain to fend off against the onslaught of Robrecht Young found themselves dying for a ruined city. Pro-Tuinstra forces had completely retreated from northern Gariepsburgh by October 5th, 1859, at which point General Young reached the shoreline of the Orange River as much of one of Riebeeckia’s largest cities stood scorched behind him.

A depiction of a fire brought about by pyrobombing during the Battle of Gariepsburgh, circa October 1859.

For the time being, however, Young would not progress across the Orange River, which soon became a natural barrier between his own army and that of General Thomas Francis Meagher of New Ireland, a former journalist and veteran of the War of Malacca who had risen through the ranks of the Riebeeckian armed forces since his days fighting against the Kingdom of Mranma. Determined to prevent the establishment of a foothold south of the Orange River by the Crusaders of Riebeeckia, General Meagher ordered the destruction of all bridges connecting northern and southern Gariepsburgh, including the famed John Quincy Adams Bridge that had become a famous landmark of the city since its construction in the mid-1840s, on October 6th in a last-ditch effort to contain Robrecht Young’s Autumn Offensive. By making the only means of crossing the Orange River via a boat, Meagher bought precious time to reinforce pro-Tuinstra defenses and created a war of attrition on the Western Front of the Riebeeckian Civil War, however, Young’s campaign of destruction had nonetheless achieved the objective of rendering Gariepsburgh of being incapable of serving as a useful port city and safe entryway to the Orange River, thus inflicting a harsh blow on the economic capacity of pro-Tuinstra provinces.

By the conclusion of October 1859, the Riebeeckian Civil War was largely a stalemate. The Karoo Front remained stagnant as Braxton Bragg continuously attempted to break Wilhelm Rosecrans’ defenses and put the Python Plan into effect whilst Robrecht Young relentlessly laid siege to Thomas Francis Meagher’s forces in southern Gariepsburgh. Naval combat between the two rival Riebeeckian governments was similarly at a standstill, with both sides more or less evenly matched in terms of naval capabilities. Ironically enough, the only frontline that was fluid and in favor of the Crusaders of Riebeeckia was the Bloemfontein Front overseen by the disgraced General James John Floyd III, whose enemy was isolated from the bulk of pro-Tuinstra provinces thanks to Bloemfontein exclusively sharing a border with pro-Breckinridge territory and the neutral Native African kingdoms. Bloemfontein held out for the time being, but General Floyd lurched closer and closer to the capital city, which was the province’s namesake, every week and a small flow of resources to Bloemfontein from Indiana and Zululand meant that the conquest of the home province of Hannibal Tuinstra was seemingly inevitable unless a bordering Native African state intervened soon.

The Riebeeckian Civil War raged on alongside a radically changing political landscape within both belligerent regimes, for neither Breckinridge nor Tuinstra and their respective allies would throw away the opportunity to implement their policy goals within the provinces they governed now that they didn’t have to deal with public officials from each other’s parties getting in the way. While Hannibal Tuinstra found himself dealing with a legislature composed entirely of Revolutionary Burrite congressmen with the exception of merely one moderate Unionist from Indiana, Samuel Breckinridge’s National Cross Party barely held a majority within the Edwardston Congress, with the Unionist Party controlling ten seats compared to the NCP’s thirteen, and the Revolutionary Burrite Party even having one congressman elected from Edwardsland. This presented a challenge for Chancellor Breckinridge, whose fringe goals would have to be navigated through what was still a pluralistic political system. Of course, the power Breckinridge wielded over both the Crusaders of Riebeeckia and the National Cross Party meant that he had all the tools necessary to become the de facto autocrat of his regime.

Very early into the Riebeeckian Civil War, the Edwardston Congress passed three key bills, retroactively titled the Consolidation Acts, which paved the way towards Samuel Breckinridge’s authoritarian rule. The first of the Consolidation Acts banned the Revolutionary Burrite Party and mandated the arrest of its party leadership and elected officials for its “acts of treason against the institutions and provinces of the United Dominion of Riebeeckia”, being voted on and put into effect on October 1st, 1828, thus resulting in the bizarre and sudden arrest of Revolutionary Burrite Congressman Edmund Sturge of Edwardston at his home just after voting against the legislation that criminalized his party. Two days later, labor unions, which had long been affiliated with the Revolutionary Burrites and the Federalists before them, were declared illegal by the Industrial Security Act. On October 6th, the Sedition Act, the final and arguably most pivotal of the Consolidation Acts was passed, which criminalized criticism of the Riebeeckian government, suspended the writ of habeas corpus, which had been upheld by the common law of the United Dominion as a product of its introduction in South Africa by the judiciary of Liberia, and gave the chancellery the unilateral authority to enforce the Sedition Act, be it through directing the Ministry of Policing and local police services or by utilizing the armed forces domestically.

The Sedition Act had been especially controversial in its passage, receiving few votes from Unionists, who feared that the powers the bill conceded to the chancellor would be abused against their own party, but nonetheless making its way through the Edwardston Congress on the basis that a strong executive with the power to purge dissent was necessary during wartime and the more general process of bringing about the Riebeeckian state envisioned in Samuel Breckinridge’s “The Crusade''. After the passage of the Sedition Act, opponents of the bill were soon proven to be correct in their fears. Publications and media critical of the Breckinridge regime were censored and their writers were imprisoned without a trial, those who behaved in contradiction to the puritanical social views of the National Cross Party were often arrested, and local Unionist and independent politicians opposed to the doctrine of the NCP were eventually arrested. The birth of Samuel Breckinridge’s theocracy was well underway as the liberal democracy forged by Aaron Burr and his compatriots was gradually crushed in northern Riebeeckia and replaced by de facto martial law.

Not even national officials were safe from the wrath of Samuel Breckinridge. The arrest of Congressman Jacobus Groenendal, the leader of the Unionist Party in the Edwardston Congress, on October 17th, 1859 due to his public criticism of the Sedition Act and the integration of pro-Breckinridge military regiments into the Crusaders of Riebeeckia proved to be the final nail in the coffin for the Unionist Party as Breckinridge used the arrest of Groenendal and the subsequent backlash from Unionist officials as an excuse to target the party’s apparatus. In what became nicknamed the Week of the Quiet Coup by media in pro-Tuinstra provinces, Samuel Breckinridge dispatched police services to arrest several Unionist congressmen and provincial government officials with a record of critiquing his most reactionary policies while Unionist ministers in his cabinet were dismissed in favor of loyal National Cross politicians. While all pro-Breckinridge provinces excluding Edwardsland and Antarctica were led by NCP-majority governments, which ensured regional collaboration in the Week of the Quiet Coup, the Unionist Party nonetheless continued boast decent public support, which led Breckinridge to largely censor media coverage of his mass detainment and promote the publication of papers decrying the Unionist Party, often including fabricated scandals and criminal activities conducted by arrested congressmen.

Of the nine Unionist congressmen serving in the Edwardston Congress when the Riebeeckian Civil War began, only four still held office by the end of October 1859 and party leadership had been crippled, therefore transforming the Unionist Party into little more than a token opposition to the National Cross Party. More importantly in terms of the ambitions of Samuel Breckinridge, the National Cross Party had now achieved the two-thirds majority necessary to pass constitutional amendments. Unsurprisingly, this power was quickly exercised by Chancellor Breckenridge, who finally had the opportunity to bring about the Christian theocratic state he had envisioned in “The Crusade'' years prior. Breckinridge introduced a slew of constitutional amendments to the Edwardston Congress throughout November 1859, titling his proposals the Scriptural Amendments. Given Samuel Breckinridge’s resounding authority over the National Cross Party, his Scriptural Amendments gradually passed with ease, being unanimously supported by all NCP congressmen.

While much of the Riebeeckian constitution was technically kept intact, the Scriptural Amendments effectively created a new system of governance and struck out a large chunk of the original constitutional articles, going as far as to rename the pro-Breckinridge United Dominion pretender government to the Holy Dominion of the Riebeeckian Confederation (HDRC), emphasizing with this new name that Riebeeckian state existed for the purpose of enforcing a Protestant theocracy upon its autonomous constituent provinces. The first of Scriptural Amendments stated their goals best with the declaration that the new regime “shall be obligated to defend, enforce, and proliferate the interests of God as outlined by the Protestant denominations of the Christian religion amongst her constituent provinces and inhabitants”. The second of the amendments clarified citizenship and voting rights, affording the former exclusively to native-born Protestants of European descent, thus institutionalizing the ethnic nationalism of the National Cross Party by stripping those who did not fit its narrow definition of a Riebeeckian citizen of basic rights and effectively leaving their fates up to the whim of the state and private interests, whereas the latter category was even more restrictive by only permitting property-owning men to vote.

Flag of the Holy Dominion of the Riebeeckian Confederation, officially adopted circa January 1860.

On top of repealing various amendments contradictory to the vision of the National Cross Party, the Scriptural Amendments generally focused on the development of a nationalist theocracy ardently committed to the interests of the white economic elite. A legislative and judicial chamber independent of Congress, named the High Court of South Africa in reference to the Medieval High Court of Jerusalem, was established with the purpose of vetoing any legislation on the national or local level incompatible with either the constitution or Protestantism, passing legislation for chancellery approval without consulting Congress, the disqualifying the political candidacy of any individual deemed subversive to the interests of the Holy Dominion, and serving as the highest court in all civil, criminal, and constitutional cases. All members of the High Court were required to be Protestant clergymen who were appointed and recalled by the chancellorship, a position in and of itself automatically reserved one of the fifteen total seats in the assembly. In effect, the High Court of South Africa served as the vanguard of Samuel Breckinridge’s theocracy through which his reactionary regime would be enforced.

The chancellorship itself was also considerably altered by the Scriptural Amendments, with the position being vested unilateral control over the armed forces and law enforcement, becoming a lifetime position, and being elected by the Congress of South Africa rather than the people. In effect, the chancellorship was transformed into an authoritarian elective monarch whose will faced no checks thanks to the sweeping power of the High Court. Outside of the structure of the national government, the Scriptural Amendments prohibited the government seizure of private property owned by citizens and prohibited the state from owning land beyond what was seized from non-citizens and necessary to carry out government functions (largely interpreted to refer to military bases and government offices). Simply put, the Scriptural Amendments and the establishment of the Holy Dominion of the Riebeeckian Confederation amounted to a counter-revolution in the name of the conservative landowning elite against decades of national Riebeeckian policies favoring economic regulation and egalitarianism, and Chancellor Samuel Breckinridge, now a de facto dictator in all but name, was the head of this counter-revolution, a synthesis of extreme laissez-faire economics, white supremacy, and theocratic nationalism.

Chancellor Samuel Breckinridge of the Holy Dominion of the Riebeeckian Confederation, circa December 1859.

Every counter-revolution needs a revolution to counter, and for the Holy Dominion, this came in the form of the pro-Tuinstra government’s very own dramatic institutional changes. Given the New Richmond Congress’ near-total Revolutionary Burrite composition, Hannibal Tuinstra had no trouble with accomplishing a goal of the RBP since its formation, that being the calling of a new constitutional convention. Some congressmen had feared that such a convention immediately after the outbreak of the Riebeeckian Civil War would prove to be divisive and provide the pro-Breckinridge regime with an excuse to decry its opponent as an illegitimate government, however, the ratification of the Scriptural Amendments and the adoption of a new name altogether Breckinridge’s state largely rendered such fears unwarranted as calls echoed through the halls of the New Richmond Congress to seize the opportunity presented by the rejection of the United Dominion’s institutions. At the behest of Chancellor Tuinstra, the New Richmond Congress would therefore almost unanimously vote on December 2nd, 1859 in favor of assembling a constitutional convention, which was to first convene in the subsequent January.

The pro-Tuinstra government was far from new to reform by the time the Scriptural Amendments had been passed. The Sixth Amendment was repealed on October 20th by the passage of the Seventh Amendment, which both eliminated the restriction on the national government with regards to expanding voting rights and automatically secured inalienable voting rights for all naturally born Riebeeckian adults upon turning twenty-one years of age and for all immigrants to Riebeeckia who had lived in the country for at least seven years, regardless of race, gender, or religion. The Eighth Amendment, which prohibited state institutions from favoring any religious denomination or financing religious organizations, passed shortly thereafter, thus securing accomplishing significant social goals of the RBP with relative ease. The welfare state later championed by Hannibal Tuinstra that began with the passage of the Reconstruction Insurance Act would likewise be expanded within the early months of the Riebeeckian Civil War via the Industrial Mobilization Act of November 3rd, 1859, which established the National Works Administration (NWA) as a public works program intended to rapidly construct wartime resources and equipment while simultaneously serving as a jobs guarantee.

All of these reforms, however, would ultimately be eclipsed by the revolution brought upon by the Austropolis Constitutional Convention. Assembling in the ruined capital of Riebeeckia in an action intended to remind the Holy Dominion that the Tuinstra regime remained in control of the national seat of power, the convention consisted of all twenty-two congressmen in the New Richmond Congress, additional delegates appointed by provincial governments to make their delegations proportional to their percentage of the national population, and, notably, representatives of various Native African tribes scattered throughout pro-Tuinstra provinces. This latter category was particularly important due to the historical exclusion of natives from national and provincial administrations largely dominated by white Ribeeckians, who had forced Native Africans off of their land over decades both through direct conflict (particularly during the colonial history of the Cape of Good Hope) and legislation that often failed to recognize tribal sovereignty over their ancestral territory.

Conventions of representatives from Native African-majority municipal and county governments, effectively the only means of Native African self-governance without the legal recognition of tribes themselves as political entities, were organized along tribal lines and elected delegates to the Austropolis Constitutional Convention throughout December 1859. Upon first convening on January 3rd, 1860, the convention was therefore unprecedented in the history of the Cape of Good Hope in that it was the first of any such body to be made up of both the descendents of settlers and Native Africans. The message being conveyed by the assembly was clear: the new government being conceived by this diverse array of delegates was not merely a continuation of the United Dominion of Riebeeckia, a nation that was ultimately an amalgamation of colonial regimes that had achieved sovereignty. It was instead to be a synthesis of various cultures, ethnicities, and regions, under a single federation, in many ways a rejection of the colonial hierarchy that had been perpetuated since the establishment of the Cape Colony in 1652.

A delegate representing the Zulu nation speaking at the Austropolis Constitutional Convention, circa January 1860.

Some elements of the new constitution were easy to determine. The country’s status as a dominion of the Germanic Empire and recognition of Empress Victoria as its head of state, for example, was politically impossible to eliminate due to the establishment of a republic being borderline inevitable suicide for the Tuinstra goverrnment by being interpreted as treason by Her Majesty and prompting a military response by the Hanoverian Realms on behalf of the Holy Dominion. Therefore, despite some grumblings from a handful of idealists who would’ve liked to do away with Germania’s sway over Riebeeckian foreign affairs and defense commitments to a distant monarch in favor of completely republican system, the convention concluded that their state was to remain a constitutional monarchy under the protection of the House of Hanover.

The structure of the legislature was likewise relatively straightforward to design. A founding principle of the Revolutionary Burrite Party had been the replacement of Ribeeckia’s apportionment system that capped Congressional representation at three seats per province with a method of proportional representation. It was therefore determined that each province would be represented in the New Richmond Congress as a multi-member district whose proportion within the national legislature would be determined by each respective province’s proportion of the national population and whose congressmen would be elected by assigning seats based on the proportion of votes won by each competing party. A new mechanism of recall elections was likewise introduced to not just Congress, but all public offices, by mandating such elections when a third of constituents approved of a recall petition, and in the case of provincial governors and delegations to the national Congress, when a simple majority of a respective province’s local legislature voted in favor of a recall election.

The executive branch of the new Cape government was a bit more contentious to design. The descent of the pro-Breckinridge provinces into autocracy had left a bad taste in the mouth of many delegates to the Austropolis Convention when it came to strong executives, therefore resulting in a wing of the convention pushing for a parliamentary system on the basis that the significant power previously under the control of the chancellery, primarily that of the armed forces, should not be under the control of a single individual for the sake of upholding a democratic system. Conversely, more moderate delegates argued that the presidential system of Riebeeckia ought to be preserved in order to maintain a separation of powers and that a centralized executive branch would ensure a more efficient government, particularly during the current civil war. After much deliberation, however, it was agreed upon, with the blessing of Hannibal Tuinstra, that the executive branch would convert to a parliamentary system where the chancellorship was appointed by the legislature, albeit a parliamentary system with an executive empowered with the position of commander-in-chief of the armed forces as an appeasement to moderate delegates.

In terms of judicial reform, proposals by a coalition of Federalists and a small handful of Revolutionary Burrites for the centralization of the judiciary under a national supreme court were quickly shot down by a strong majority of delegates in favor of preserving the decentralized common law structure of the United Dominion. Judges were, however, required to be democratically elected by the people encompassed by the authority of their courts as a means of ensuring that the judicial process was accountable to public interest as opposed to regional governments. Beyond the structure of the legislature, executive, and judiciary, the outlining of the broad political system of the new constitution came down to some minor additions, such as prohibiting local governments from nullifying the laws of higher administrations so as to prevent a repeat of the Nullification Troubles and the constitutional right for the national government to impose conscription during wartime in a controversial reaffirmation of the Third Amendment of the Riebeeckian constitution, the ratification of which by the Austopolis Convention was largely informed by the present circumstances of Hannibal Tuinstra’s government making conscription incredibly tantalizing.

The Austropolis Convention likewise reiterated the egalitarian amendments upheld by the Revolutionary Burrites and the Federalists before them, simply restating the second, fourth, fifth, seventh, and eight amendments to the Riebeeckian constitution, thereby enshrining equal voting rights for all South African adults, campaign finance limits, the right to a free public education, and the separation of church and state within the new document. Riding off of anti-corporate sentiments that were fueled by opposition to the laissez-faire economic doctrine of the Holy Dominion, the Austropolis Convention would actually go a step further than the original Fourth Amendment by outright abolishing the financing of political campaigns by individual contributions and instead established a mechanism of public campaign finance for all political offices, the first of such a system in the world. Under the new constitution, all voting age citizens were allocated a sum of money (determined by national and local legislatures) each year that they could only spend on political campaigns and parties, and it was exclusively through these vouchers that campaigns and parties could accumulate funding for their endeavors.

The most significant elements of the document written and ratified by the Austropolis Convention were undeniably its socio-economic reforms. Unbeknownst to the delegates assembled in the ruined capital city, it was these policies in particular that would ultimately lay the groundwork for much of the Equatorial Commonwealth and go onto define the concept of the modern welfare state up until the Cold War and the radicalization of the world of the early 20th Century. The establishment of strong welfare programs had long been a core tenant of the Revolutionary Burrite platform due to the party’s populistic and working class origins, and as such the convention set about developing a political structure that prioritized the economic well-being of those who it governed. After much debate, the Austropolis Convention passed one of its most significant reforms by constitutionally enshrining the right to healthcare services and nationalizing the entirety of the healthcare industry, which was subsequently placed under the management of the newfound Ministry of Health Services following the ratification of the Austropolis Convention’s constitution.

Largely ratified at the behest of social reformers and military commanders such as Otto Bismarck, who perceived universal healthcare was as an efficient means of both providing for a population devastated by warfare and ensuring national loyalty to the Tuinstra government, the nationalization of health services was merely the beginning of an economic and political system that Chancellor Hannibal Tuinstra characterized as Burrite democracy in his writings regarding the Austopolis Convention. Defined as a socially and economically progressive form of liberal democracy that could trace its roots back to the ideology of Aaron Burr (linking the values of the Tuinstra government to those of the Father of Riebeeckia was a blatant move for ideological legitimacy in the civil war), Burrite democracy as an ideology believed that representative administrations were responsible for providing for the well-being, equality, and general social justice of their constituents through economic regulation, the provision of large welfare programs, a mixed economy, and wealth redistribution. This definition of the general views of the Austropolis Convention stuck, and by the time the new constitution was ratified, the pro-Tuinstra provinces would have their own revolutionary ideals to rally behind.

Soon, much of the Indian Ocean would follow suit in the revolution for Burrite democracy.

Beyond universal healthcare, further economic reforms were pursued by the Austropolis Convention that upheld the ideals of Burrtie democracy. The new constitution notably gave public administrations the ability to redistribute wealth and assets, nationalize privately-held assets and industries, and significantly regulate and oversee production within the private sector to a degree that permitted limited economic planning. In terms of labor rights, private sector workers were guaranteed the constitutional right to unionize, participate in striking activities so long as the union’s actions were “lawful and peaceful”, and undergo collective bargaining arrangements with their employer. Two final economic reforms of significance that were implemented by the Austropolis Convention included the constitutional right to social insurance intended to aid the disabled and elderly and a guaranteed minimum income of equal wealth distributed to every adult citizen once every six months, thus accomplishing two policy goals of more radical social progressives since the days of the Age of Enlightenment.

Once the Burrite economic system of the pro-Tuinstra provinces was fully developed, the Austropolis Convention turned to one last issue before ratification, that being the autonomy of Native African nations. Delegate Adam Kok III of the Griqua people would propose an article to the convention that sought to establish the right for each Native African nationality within Riebeeckia to autonomously govern itself as a province within the wider apparatus of state. While provincehood for each tribe within South Africa failed to find support within the halls of the Austropolis Convention, the controversial notion of establishing provinces for Native African communities gradually began to catch on amongst delegates. In the eyes of the socially progressive convention, the introduction of Native African provinces ultimately became critical to casting aside the colonial hierarchies that had persisted in southern Africa since the arrival of Jan Van Riebeeck himself. As such, while the establishment of new provinces was deemed outside of the jurisdiction of the Austropolis Convention, delegates nonetheless crafted a collection of legislation that would see the provinces of Khoikhoi, Griqualand, West Zululand, and Molopo be admitted into the pro-Tuinstra government by the legislators present at the convention and extended the invitation of provincehood to any tribe within pro-Breckinridge territory that aligned itself with the New Richmond Congress during the Riebeeckian Civil War.

To symbolize this transition of the pro-Tuinstra government away from the historical domination of the Cape of Good Hope by settler colonial regimes and towards a federation of settler and native communities, the Austropolis Convention concluded their work by deciding that a new name was needed, given that the identity of Riebeeckia as a direct descendent of the preceding Dutch colonial regime was to be abandoned. After much deliberation, the Austropolis Convention determined that the name of their new Burrite democracy was to be the United Provinces of Azania, and this new nation was officially brought into existence upon the ratification of her constitution by the Austropolis Convention on February 8th, 1860. The United Provinces of Azania now stood in direct contrast to the ideals of the Holy Dominion of the Riebeeckian Confederation, with both states being determined to bring about their vision of a new South African government to the entirety of the now-dead United Dominion. In the north, the banner of Samuel Breckinridge’s theocracy flew, whilst in the south, Burrites hoisted the banner of their new union of Azania.

Flag of the United Provinces of Azania, officially adopted circa March 1860.

Following the formation of the United Provinces, the New Richmond Congress quickly set about re-electing Hannibal Tuinstra to the chancellorship under the new parliamentary system of their regime while the politicians of the Holy Dominion decried the Azanian state as a betrayal and fundamental threat against the Riebeeckian way of life. Watching from afar in the chambers of Hanover, the Germanic Empire maintained a position of neutrality throughout the Riebeeckian Civil War, recognizing that both factions were openly loyal to the crown of Her Majesty Empress Victoria and regarding intervention on the Cape of Good Hope as bad for commercial interests in the region, although this wasn’t to say that there were not those in Germania who favored one belligerent over the other. Speaker of the House of Commons Heinrich von Gagern, while not advocating for military intervention on behalf of one faction or the other, decried the Holy Dominion of the Riebeeckian Confederation as a vile backlash against the liberalization that had swept both Europe and the wider world for the past century and futilely attempted to get the Germanian state to recognize Azania as the legitimate South African domain of Victoria in the face of backlash from the conservative Imperial Union Party and nobility.

In what was both a compromise between supporters of Tuinstra and Breckinridge and a means to protect Germania’s economic interests in South Africa, the Bundesrat passed the Neutrality Act on November 1st, 1859, which stated that the Germanic Empire would not officially favor one South African government over the other so long as both regimes upheld the United Dominion of Riebeeckia’s commitments to the House of Hanover and did not interfere in the Hanoverian Realms trading with either government. The legislation also notably allowed for Germanian citizens to finance and fight on behalf of factions in the Riebeeckian Civil War as volunteers, an element of the bill that revolutionaries and reactionaries alike took advantage of. Facing the prospect of a world power, her colonies, and the mighty dominion of the Kingdom of India intervening on behalf of their enemy, both Tuinstra and Breckinridge had little choice but to respect the Neutrality Act, and an awkward situation emerged where merchants from Amsterdam found themselves trading with businesses in Edwardston only to sail south past a warzone to trade with the Edwardston capitalist’s enemy down in Zomerstadt.

Going into the winter and subsequent spring of 1860, the frontline between Azanian and Confederate forces began to become fluid yet again. 1859 was closed out with the Battle of Moses City, a brutal siege that lasted several weeks. Encircled on all sides by the pro-Breckinridge province of Noordelijk, the Moses City Territory had nonetheless remained loyal to Hannibal Tuinstra due to its history as a bastion of progressivism and racial equality despite its location in an otherwise socially conservative stronghold of Riebeeckia. Moses’ isolation from other territory under the control of the Revolutionary Burrite Party meant that its occupation was inevitable, however, the city’s ethnic makeup being primarily of Gullahs and other freedmen from the Americas meant that capitulation to the reactionary Breckinridge regime was an impossibility. With limited defenses, the Moses City Territory would live on borrowed time, hoping that the emerging Riebeeckian Civil War would be a brief conflict.

An army of the Crusaders of Riebeeckia under the command of General Stephanus Schoeman, a War of Malacca veteran-turned-fiery statesman who had served in the Noordelijk provincial legislature before resigning to return to military service upon the outbreak of the Riebeeckian Civil War began besieging the outermost defenses of Moses City on October 19th, 1859, a little over a month following the outbreak of the wider conflict once it became clear that naval blockades weren’t enough to bring Moses to its knees. Given that the Battle of Moses City was far from a priority of a government waging a much larger conflict in its south, General Schoeman’s army was considerably smaller than anything Tuinstra regimes were facing on the main frontlines of the Riebeeckian Civil War were forcing, but even so, Moses City’s ability to hold out for several months against a relentless invading force boasting much greater manpower was an impressive feat. Much of Moses City was burning by the end of October alone, however, the guardians of the ruined City of Emancipation continued to hold out for another two months.

Having earned a reputation as a destination for freed slaves throughout the world since its establishment in 1837, Moses City and its struggle against the Crusaders of Riebeeckia particularly resonated with the global community, and abolitionist groups in the Americas were especially keen on raising funds to aid in the defense of Moses. Prime Minister Benjamin Lloyd Garrison of the Federated Republic of Albionora, already a vocal critic of the political reaction of Samuel Breckinridge and the National Cross Party, decried the indiscriminate carnage of the Crusaders in the Battle of Moses City as a “blatant confirmation to the world of the Edwardston regime’s fondness for the most evil institution known to man, a manifesto transcribed in blood and fire”, and not only officially recognized Hannibal Tuinstra’s government as the legitimate regime in Riebeeckia, but also passed the so-called South Africa Act through the Parliament of Albionora circa late November 1859, which lended resources, military equipment, and humanitarian aid to the pro-Tuinstra government. Meanwhile, various privateer fleets mostly assembled by Albionorians and Columbians but also notably consisting of Germanians, Brazilians, Peruvians, and Kongolese fought against the blockade of Moses City upon the waves of the Atlantic Ocean whereas volunteer militias rode aboard these fleets with the hope that they would step foot in the burning city to fend off its destruction.

Even a coalition of sympathetic movements throughout the Western world could not, however, protect Moses City from its ultimate defeat. Supplies to and within the urban center would eventually run thin, the Crusaders made progress into Moses’ interior day by day, and pyrobombing was introduced to the Battle of Moses City by Stephanus Schoeman’s forces in late November 1859, all indicating that Jack Pritchard’s dream of a city for the freed Gullah people was coming to a brutal end. It was within these closing days of the Battle of Moses City that Araminta Ross, a former slave from Virginia who had been freed during the purchase and subsequent emancipation of North American slaves by Jack Pritchard and his colleagues in the 1830s, rose to prominence as a soldier within the army defending Moses City. Having taken up arms in the Riebeeckian Civil War upon the beginning of the battle for her home city, Ross had endured the entirety of the brutal siege and had risen through the ranks of local forces due to her tactical insight, being a lieutenant by the dawn of December 1859.

After the Crusaders of Riebeeckia broke through the final line of defenses in the city on December 9th, 1859, Governor-General David Hunter ordered the complete withdrawal and evacuation of pro-Tuinstra forces from the northernmost battlefield in the Riebeeckian Civil War. Citizens and soldiers alike quickly rushed to warships over the coming week in a desperate scramble to flee the Holy Dominion’s wrath, with many of these ships ultimately sinking to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean at the hands of Confederate cannons, however, Lieutenant Ross made it clear to her superiors that she refused to leave Moses City until the last evacuating ship carrying civilians had escaped the ports of northern Riebeeckia. On December 12th, 1859, in a last ditch effort to buy the evacuation some extra time, Lieutenant Araminta Ross led a raid on a Crusader battalion to the north of Moses’ port, and despite her forces sustaining heavy casualties in the face of her enemy’s organ guns, Ross nonetheless managed to not only deter the encroaching offensive to her north, but ultimately push it back a handful of ruined city blocks, thus temporarily halting Schoeman’s offensive for a few days. The story of a successful counter-offensive by a former slave in Moses City, a manuever that was credited for critically keeping the territory’s port in pro-Tuinstra hands for two additional weeks as the last civilian ships fled the scene, was widely circulated throughout southern Riebeeckia and Araminta Ross was greeted as a national hero upon arriving in New Richmond on December 26th with a pivotal career in the coming war ahead of her.

A sketch of Araminta Ross following the Battle of Moses City, circa January 1860.

Of course, not even the bold actions of Ross could save Moses City from its conquest, and mere hours after the last pro-Tuinstra warship left the metropolis’ harbors, General Schoeman finally declared victory in the Battle of Moses City on December 24th, 1859. Under decree from Chancellor Samuel Breckinridge, the occupied Moses City Territory was subsequently absorbed into the province of Noordelijk, undoing what the National Cross Party largely regarded as an unjust theft of land from white Noordelijk landowners back in 1837. Under the supervision of General Schoeman, the Noordelijk provincial government would undertake a campaign of brutal ethnic cleansing in the occupied Moses City, hoping to wipe out a northern stronghold of egalitarian thought in Riebeeckia and arguably a physical symbol of the Revolutionary Burrite Party’s ideals. Black civilians unable to escape Moses City were forcibly removed from their homes, and the vast majority of these civilians were relocated to prisoner of war camps due to the Holy Dominion lacking any alternative institution for such a large population, where conditions were remarkably inhumane. In the aftermath of what southern newspapers condemned as the “Eradication of Moses City'', the municipality was renamed to Samuelston in honor of the Confederate chancellor and was opened to settlement by white Protestant families.

The aftermath of the Battle of Moses City was marked by more strategically significant advancements by the Holy Dominion on various frontlines, with January and February seeing the continued defeat of pro-Tuinstra forces in Bloemfontein (and later Griqualand following the formation of said province), who remained the victims of isolation from allied territories. The newly-founded Griqualand administration fell prior to Bloemfontein itself, and while establishment of sovereignty for the Griqua people created a brief setback for James John Floyd III’s advance by allowing for better self-management of local defenses, the fact of the matter was that much of Griqualand’s recognized territory had already been occupied by the Crusaders of Riebeeckia well before the province’s creation. The Battle of Philippolis on February 17th, 1860, only a little more than a week following the official formation of the United Provinces of Azania, marked the last stand for Griqualand as the Azanian National Army (ANA) held out in the province’s besieged capital. It was, however, seemingly an inevitability that the Crusaders would emerge victorious in the Battle of Philippolis, given that the Azanian forces were outnumbered, running short on military equipment, and on the brink of starvation. It was therefore no surprise when the Confederate flag of crimson, white, and black was flying over a burning Philippolis by the end of the day while provisional Governor Adam Kok III of Griqualand had fled to the city of Bloemfontein to administer a provincial government-in-exile.

It would not be much long after Kok’s evacuation that Bloemfontein itself fell under Confederate occupation. Having been unable to adequately resupply itself since the outbreak of the Riebeeckian Civil War, the home province of Hannibal Tuinstra was living on borrowed time. Demoralized ANA regiments had become dependent on constant conscription and collaboration with local paramilitaries in order to keep their operations afloat whereas civilians had grown disgruntled with a collapsing war economy, where basic needs for working-class Bloemfonteinians were increasingly difficult to come by. The Azanians managed to put up a strong fight against General Floyd’s army at the Battle of Bloemfontein, which started with a small raid on the city’s outskirts on February 26th, 1860, however, much like at Philippolis, a Confederate victory was inevitable. The infamously slow and cautious tactics of James John Floyd III meant that the Battle of Bloemfontein was an engagement much more protracted than necessary, however, after three days of combat, the Crusaders of Riebeeckia had decisively uprooted the ANA from the last major city within the Bloemfontein and Griqualand provinces on February 29th, 1860.

With their significant settlements completely lost to the Holy Dominion, the defense of Bloemfontein and Griqualand was regarded to be a lost cause by the Azanian high command going into March 1860, and the vast majority of ANA soldiers on the Bloemfontein Front were forced into capitulation and became prisoners of war. Other regiments managed to awkwardly sneak their way through the Native African kingdoms of southern Africa to other Azanian territory whilst a handful of bold forces stayed behind, hiding in the wilderness and rural landscape of Bloemfontein and Griqualand to operate as a patchwork of guerrilla militias, who media ultimately nicknamed Bushwhackers. With activities ranging from the sabotage of Crusader supply lines to rapid, and oftentimes brutal, raids on settlements occupied by Confederate forces, the Bushwhackers soon gained the reputation of terrorists amongst the citizenry of the Holy Dominion and a cloud of controversy as to whether or not they were outlaws to be feared or heroes to be adored amongst the citizenry of Azania.

Three Bushwhackers who were active in Confederate-occupied Bloemfontein, circa May 1860.

The conquest of Bloemfontein and Griqualand in turn provided for the reallocation of the Bloemfontein Front’s resources to the much more pivotal Western and Karoo frontlines. These reinforcements were not substantial, and Azanian defenses in Gariepsburgh were too substantial to give Robrecht Young an opportunity to advance over the Orange River, however, they were enough to give way to a brief gain in territory into Zomerland by General Braxton Bragg. The so-called April Offensive saw Bragg lead a rapid assault against Wilhelm Rosecrans through the Great Karoo, bringing the agrarian half of the Zomerland under Confederate rule by the end of the month, however, this quick success was not to last. General Bragg, for all of the admiration he won from Samuel Breckinridge and Edward J Jackson for his progress in pursuing the Python Plan, lacked in his post-battle follow-up strategies and imaginative combat tactics. This left Confederate occupied territory in the Great Karoo vulnerable to its north and south while supply lines increasingly ran thin as Bragg’s army encompassed a larger and larger swath of land.

More importantly, the odds were beginning to be stacked against the Holy Dominion in general. The simple fact of the matter was that the United Provinces of Azania boasted a larger population and industrial capacity than the more agrarian Holy Dominion of the Riebeeckian Confederation, and while pro-Tuinstra armed forces had been relatively disorganized at the onset of the Riebeeckian Civil War thanks to the lack of any equivalent to the Crusaders of Riebeeckia for its military apparatus to be integrated within, these issues had long since been resolved, especially with the formation of the United Provinces. This, combined with the conscription of thousands of young Azanian men into the ANA meant that the Burrite revolution had the capacity to defeat its reactionary opponent through demographic advantages alone. The window for the quick victory the HDRC required to emerge victorious in the Riebeeckian Civil War had arguably elapsed by April 1860, and the tacticians in New Richmond insisted to Chancellor Tuinstra that, so long as the Azanian state continued to relentlessly focus on defeating the Holy Dominion, victory was only a matter of time.

In the short term, this meant the complete undoing of the April Offensive’s victories. While smaller armies chipped away at Confederate territory from the north and southeast, a growing force commanded by General Rosecrans took it upon itself to lead a counteroffensive towards South Holland in May 1860. Over the span of said month, Bragg saw the conquests he had become so famed for throughout the Holy Dominion undone by the organ guns of Rosecrans’ increasingly large army while his own forces found it increasingly difficult to make up for losses. Rosecrans would first enter South Holland on May 25th, 1860 upon emerging victorious in conquering the small border town of Williamstadt in the southwestern reaches of the province, thus marking the first incursion of the ANA into a Confederate province. Going into the subsequent June, the roles of Rosecrans and Bragg had clearly reversed from where they were just two months prior, with the former leading a rapid offensive into a province defended by the latter, and without a significant shift in the situation of the wider Riebeeckian Civil War, this would be where their roles would remain situated.

To make matters worse for the Holy Dominion, as Wilhelm Rosecrans led his invasion into South Holland, the Iron General prepared to make his next move during the dawn of the summer of 1860. Having mainly served as an armchair general since his victory at the Battle of Austropolis who divided his time between overseeing the overall tactics on the various frontlines of the Riebeeckian Civil War and serving as an indispensable advisor to Chancellor Tuinstra’s government as its Minister of War, the famed Otto Bismarck gradually took notice of an exposed underbelly in Confederate defenses along the border of New Hanover and Binnenland. Both provinces’ boundary with Azania was primarily sparsely-populated rural territory, and as the Holy Dominion focused on its push along the western coastline and into Zomerland in accordance with the Python Plan while pro-Tuinstra forces had concentrated their efforts on defending against these advances, the agrarian region had been ignored. But now that the Crusaders were on the run, General Bismarck wagered that a well-armed offensive by Azanian forces along the Nossob River would at least divert significant resources away from Robrecht Young’s efforts on the Western Front and, at best, provide a long term launching pad for an Azanian invasion into the heart of Confederate territory.

Therefore, with permission from Hannibal Tuinstra, the Azanian Minister of War left from New Richmond to the newly-established Molopo province of the Nama people with an army equipped with road locomotives and steam-powered elephas to push along the coastline of the Nossob River into southeastern New Hanover. Bismarck’s calculation that local battalions guarding the rural outskirts of the Holy Dominion would be greatly overwhelmed by his mechanized force of armored infantry proved to be precisely correct, and starting on June 10th, 1860 with the Battle of Bokspits, the Nossob Offensive proved to be a resounding success. The Azanian National Army rapidly covered a considerable chunk of territory as its metal beasts of the Industrial Revolution rampaged over Confederate farmland, with Bismarck arriving at the confluence of the Auob River and the Nossob River on June 22nd, within a little less than two weeks since the start of his groundbreaking offensive.

General Otto Bismarck mounted on a horse outside of a farmhouse seized by the Azanian National Army, circa June 1860.

The Nossob Offensive was sure to be the kick in the Confederate stomach needed by the United Provinces to bring a swift conclusion to the Riebeeckian Civil War. Wilhelm Rosecrans continued his campaign into South Holland, slowly but surely chipping away at the defenses of General Braxton Bragg, while Thomas Francis Meagher held his own on the Western Front against Robrecht Young, who was being pressured by his superiors to reallocate forces to Bismarck’s Molopo Front, in turn weakening the Crusaders’ holdout in northern Gariepsburgh. Day by day, the Holy Dominion of the Riebeeckian Confederation was being pushed ever closer to the brink of a total collapse in its defenses at the hands of her enemy. Word began to spread through the streets of New Richmond and Edwardston alike that all of Riebeeckia would be brought under the banner of the United Provinces by the end of the year, and while military officers generally refrained from making such bold predictions, not even they could avoid the whispers that the arsenal of Burrite democracy would soon be parading through the streets of Edwardston.

Of course, the Riebeeckian Civil War was not to be such a simple conflict. This was not merely a typical civil war, but rather the prelude to a wider conflict spanning the entirety of the Indian Ocean and the great powers of her waves. Unbeknownst at the time, the Austropolis Convention and its development of Burrite ideals had fermented the seeds of revolution well beyond the borders of the fallen United Dominion. In the Kingdom of India, elites and the masses alike debated both the militaristic and philosophical developments emerging from their fellow Hanoverian Realm, bolstering a fledgling movement for liberalization within a mighty empire in its own right. In the Native African kingdoms, once protectorates of Riebeeckia that had since clung onto a policy of neutrality during their former guardian’s civil war, radicals latched onto the ideology of Burrite democracy in protest of the absolutist rule of their various monarchs in a hope to export Hannibal Tuinstra’s revolution abroad. And in the Mutapa Empire, Mwene Changamire Chatunga watched the Azanian revolutionary tide in abject fear of international proliferation while cozying up to the idea of collaboration with the Holy Dominion of the Riebeeckian Confederation, a fellow Protestant theocracy.

No, the Riebeeckian Civil War was not destined to conclude in 1860. On both the battlefield and in the chambers of politicking, the heirs to the throne of Aaron Burr’s federation had unleashed what would ultimately develop into the wider Equatorial Revolutionary War as the various monarchies of the Indian Ocean watched in anticipation. Burrite democracy and Samuel Breckinridge’s had already been quietly consolidating allies throughout the wider world, and it was unknowingly only a matter of time until the first domino was toppled in a chain of events that were to pull the entire region into the fiery conflict between revolutionary progressivism and counterrevolutionary theocracy. Soon, the Riebeeckian Civil War was to be overshadowed by a much more grand and important Equatorial Revolutionary War that was to encompass hundreds of millions of lives and permanently define the course of human history. And where, you may inquire, was this first domino to descend? It subtly began to fall in the streets of Nxuba, the capital of the Xhosa Federation.

“We’ll fight in the name of Father Burr, hurrah, hurrah!

We'll fight in the name of Father Burr, hurrah, hurrah!

Fight for Father Burr’s democracy, fight for the rights of you and me!

In the name of Father Burr!”

-Excerpt from “Fight in the Name of Father Burr”, a wartime song popularized in the United Provinces of Azania during the Equatorial Revolutionary War.