Hello Everyone! This is a timeline that will show a world where the United States of America lost the Revolutionary War, however, the legacy it left behind will continue to influence the world for decades to come. The first chapter will be a "pilot" to see if people like this timeline and if they do I'll continue it! Anyway, I hope you enjoy this and please vote in the poll!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dreams of Liberty: A Failure at Princeton

- Thread starter ETGalaxy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 68 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Jeremy Bentham Wiki Infobox Chapter Thirty-Two: A House Divided Map of the United Dominion of Riebeeckia Circa 1859 Riebeeckian chancellery election 1859 Chapter Thirty-Three: The Shot Heard Around the World United Dominion of Riebeeckia Wiki Infobox Chapter Thirty-Four: Revolution and Reaction Map of the Mutapa Empire Circa September 1860

Title

DREAMS OF LIBERTY

A FAILURE AT PRINCETON

"We owe a lot to our brethren in Columbia. If it wasn't for them perhaps the Commoner's dream of liberty would have never been realized."

-Jeremy Bentham

The Age of Enlightenment (1776-1799)

Chapter One: The Columbian UprisingA FAILURE AT PRINCETON

"We owe a lot to our brethren in Columbia. If it wasn't for them perhaps the Commoner's dream of liberty would have never been realized."

-Jeremy Bentham

The Age of Enlightenment (1776-1799)

Chapter Two: The Seeds of Liberty

Chapter Three: Viva La France!

Chapter Four: The French Civil War

Chapter Five: Death To An Empire

Chapter Six: Chaos in Columbia Part One

Chapter Seven: Chaos in Columbia Part Two

The Benthamian War (1799-1801)

Chapter Nine: Blood in the Biscay

Chapter Ten: The Dusk of an Era

Chapter Eleven: Across the Alpines

Chapter Twelve: The New Europe

The Noble Game (1801-1859)

Chapter Fourteen: The Nations of America

Chapter Fifteen: Mfecane

Chapter Sixteen: Crisis in the Balkans

Chapter Seventeen: Hail Germania Part One

Chapter Eighteen: Hail Germania Part Two

Chapter Nineteen: From Concord to Charleston

Chapter Twenty: Into the Sunset Part One

Chapter Twenty-One: Into the Sunset Part Two

Chapter Twenty-Two: The World Beneath the Equator

Chapter Twenty-Three: Fight as a Lion

Chapter Twenty-Four: Never Interrupt Your Enemy When He is Making a Mistake

Chapter Twenty-Five: The Wreath and the Cross

Chapter Twenty-Six: Look to the East

Chapter Twenty-Seven: The Room Where it Happens

Chapter Twenty-Eight: The Decade of Despair

Chapter Twenty-Nine: The Bourbon War Part One

Chapter Thirty: The Bourbon War Part Two

Chapter Thirty-One: Empires of Africa

The Equatorial Revolutionary War

Chapter Thirty-Two: A House Divided

Chapter Thirty-Three: The Shot Heard Around the World

Chapter Thirty-Four: Revolution and Reaction

Last edited:

Chapter One: The Columbian Uprising

Chapter One: The Columbian Uprising

“IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America

when in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

-The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America.

When reflecting upon the past many cite the Great London Coup as the dawn of the world we live in today. Without the Great London Coup there would be no Benthamian War, without the Benthamian War there would be no Industrial War, and without the Industrial War there would be no Radical Wars.

However, just as the Great London Coup toppled the dominoes that would lead to the events that defined the next two centuries there were events prior to the Great London Coup that toppled the dominoes that led to the rise of the Radicals. One such event was the Columbian Uprising, the short war in which thirteen British colonies in North America (now referred to as the Columbian Colonies) rebelled under a singular banner, that of the United States of America.

Flag of the United States of America being flown on July 4th, or Columbia Day, in the Republic of Concordia.

The birth of the USA began after the Seven Years War, or the French-Indian War as the Americans referred to it. The global conflict was primarily between the two colonial powers, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of France, and their colonies in North America had been one of the most prominent frontlines. In the aftermath of the Seven Years War the Columbian Colonies were taxed by their rulers in Europe in order to pay off Great Britain’s debt. The Columbians were angered by the tax and began to protest the British, with one very significant act of disobedience being the Boston Tea Party. Tensions between Columbia and King George III only continued to grow and by the year of 1776 the concept of an independent Columbian state was very popular.

In 1774 the Continental Congress, a convention of delegates from all thirteen of the Columbian Colonies, would meet for the first time in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where Benjamin Franklin convinced the Congress to form a representative body. The second time the Congress would meet was on July 2nd, 1776 when they would pass a resolution asserting independence with no opposition. Just two days later the Columbian Colonies would declare independence from Great Britain as the United States of America, a confederation of the colonies with the Seven Years War veteran George Washington as the general of the new nation’s military.

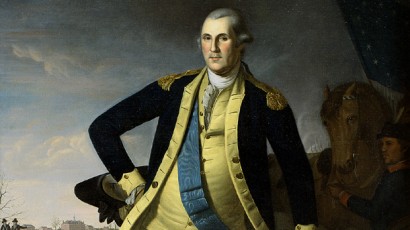

General George Washington of the United States of America.

Despite the USA declaring its independence in 1776 the first battle of the Columbian Uprising was on April 19th, 1775 when the British attempted to disarm the Massachusetts militia at Concord resulting in open combat between the two forces. The militia would later siege Boston a year later in March and forced the British military to evacuate the city. Under the leadership of Sir William Howe the British launched a counteroffensive after the USA was declared and captured New York City. Perhaps one of the most decisive battles of the entire war was the Battle of Princeton when General Washington and his forces crossed the Delaware River on January 3rd, 1777. After winning at Trenton Washington advanced into Princeton, however, was spotted by a British spy who warned General Cornwallis of the upcoming attack, giving the British time to prepare for the attack. The Americans would win the Battle of Princeton, however at a costly price. In one swift decision, Charles Mawhood pulled the trigger on his rifle, only for the smoke the reveal that General George Washington had been shot and killed.

With one bullet, the history of the Columbia Uprising, and possibly the world itself, was permanently altered.

The Martyr of the Revolution, a painting that depicts General George Washington before charging to this death at the Battle of Princeton.

At first, the Americans would continue to advance under the command of General Washington’s second-in-command, Alexander Hamilton, however, the Continental Army was eventually pushed back and were forced to flee Princeton due to poor organization amongst the forces of Hamilton in contrast to the excellent prepared organization of the British. After evacuating back to Trenton, the long-term effects of Washington’s death would be seen a bit later when the time came to select a new commander for the Continental Army. Alexander Hamilton was suggested, however, his failure at Princeton would mean that Anthony Wayne became the new head of the American military instead. Wayne would prove himself to be nowhere nearly as skilled as General Washington and his fiery personality would become a serious flaw that would affect both his tactics and the United States in general.

General Anthony Wayne of the United States.

Starting in June 1777 the British would invade from Quebec into New England under the leadership of John Burgoyne and William Howe under what became known as the New England Campaign. While Howe had considered going after Philadelphia, the capital of the United States of America and current location of General Anthony Wayne, as soon as reinforcements arrived following the success of the precious winter William Howe guaranteed Burgoyne that he would be pushing north for Albany. The Campaign was intended to isolate New England and proved to be very successful. The British would succeed at defeating General Wayne and the United States became very demoralized.

After the end of the New England Campaign in the fall of 1777, General William Howe turned south to invade Pennsylvania and the Americans would only continue to lose to the British until General Howe found himself fighting in the capital of America itself, Philadelphia. On December 14th, 1777 the Americans lost their capital and the Union Jack was raised above the Philadelphia State House. By this point most of the Continental Congress had given up, the military was on the brink of revolt, and even New England, the last bastion of support for the Columbian Uprising, was demoralized after nearly a year-long blockade and siege, so the decision to finally surrender to Great Britain on December 16th, 1777 was an easy one.

The Treaty of Saratoga would be signed just a day after the USA surrendered and reintegrated the Columbian Colonies back into the Kingdom of Great Britain. However, the colonies would be punished with their former governments that had rebelled obviously being replaced. William Howe actually became the governor-general of Pennsylvania while John Burgoyne became the governor-general of New York. Massachusetts would also have to grant independence to Maine as a new colony, and the former territory of the First Vermont Republic was separated from New York as yet another colony.

The British were intent on preserving the Indian Reserve (more commonly known as the Appalachian Colony) west of the 1763 Proclamation Line, whose partition was one of the main causes of the Columbian Uprising to begin with, however, this region’s territory had been stripped away for nearly a decade by British colonial administrations, and this would continue to be the case even after the humiliation of the Columbian Colonies in 1777. William Howe’s Pennsylvania would be extended west to the border of the Province of Quebec in 1780, and under the leadership of Governor-General George Germain of Virginia quickly expanded his colony’s territorial authority in 1779 with little resistance due to the already existing Virginian influence in the region of the present-day Province of Vandalia.

The Columbian Uprising was a brief conflict that the British were destined to win, however, the consequences it had on world history were immense. In the aftermath of the war former supporters of the USA trekked west for the Spanish colony of Louisiana while others would travel to the Cape of Good Hope and became the seeds of democracy. Another significant role the Columbian Uprising played in history was the United States becoming an inspiration for the French commoners that would create the world's first great democracy.

The signatories of the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America.

“IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America

when in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

-The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America.

When reflecting upon the past many cite the Great London Coup as the dawn of the world we live in today. Without the Great London Coup there would be no Benthamian War, without the Benthamian War there would be no Industrial War, and without the Industrial War there would be no Radical Wars.

However, just as the Great London Coup toppled the dominoes that would lead to the events that defined the next two centuries there were events prior to the Great London Coup that toppled the dominoes that led to the rise of the Radicals. One such event was the Columbian Uprising, the short war in which thirteen British colonies in North America (now referred to as the Columbian Colonies) rebelled under a singular banner, that of the United States of America.

Flag of the United States of America being flown on July 4th, or Columbia Day, in the Republic of Concordia.

The birth of the USA began after the Seven Years War, or the French-Indian War as the Americans referred to it. The global conflict was primarily between the two colonial powers, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of France, and their colonies in North America had been one of the most prominent frontlines. In the aftermath of the Seven Years War the Columbian Colonies were taxed by their rulers in Europe in order to pay off Great Britain’s debt. The Columbians were angered by the tax and began to protest the British, with one very significant act of disobedience being the Boston Tea Party. Tensions between Columbia and King George III only continued to grow and by the year of 1776 the concept of an independent Columbian state was very popular.

In 1774 the Continental Congress, a convention of delegates from all thirteen of the Columbian Colonies, would meet for the first time in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where Benjamin Franklin convinced the Congress to form a representative body. The second time the Congress would meet was on July 2nd, 1776 when they would pass a resolution asserting independence with no opposition. Just two days later the Columbian Colonies would declare independence from Great Britain as the United States of America, a confederation of the colonies with the Seven Years War veteran George Washington as the general of the new nation’s military.

General George Washington of the United States of America.

Despite the USA declaring its independence in 1776 the first battle of the Columbian Uprising was on April 19th, 1775 when the British attempted to disarm the Massachusetts militia at Concord resulting in open combat between the two forces. The militia would later siege Boston a year later in March and forced the British military to evacuate the city. Under the leadership of Sir William Howe the British launched a counteroffensive after the USA was declared and captured New York City. Perhaps one of the most decisive battles of the entire war was the Battle of Princeton when General Washington and his forces crossed the Delaware River on January 3rd, 1777. After winning at Trenton Washington advanced into Princeton, however, was spotted by a British spy who warned General Cornwallis of the upcoming attack, giving the British time to prepare for the attack. The Americans would win the Battle of Princeton, however at a costly price. In one swift decision, Charles Mawhood pulled the trigger on his rifle, only for the smoke the reveal that General George Washington had been shot and killed.

With one bullet, the history of the Columbia Uprising, and possibly the world itself, was permanently altered.

The Martyr of the Revolution, a painting that depicts General George Washington before charging to this death at the Battle of Princeton.

At first, the Americans would continue to advance under the command of General Washington’s second-in-command, Alexander Hamilton, however, the Continental Army was eventually pushed back and were forced to flee Princeton due to poor organization amongst the forces of Hamilton in contrast to the excellent prepared organization of the British. After evacuating back to Trenton, the long-term effects of Washington’s death would be seen a bit later when the time came to select a new commander for the Continental Army. Alexander Hamilton was suggested, however, his failure at Princeton would mean that Anthony Wayne became the new head of the American military instead. Wayne would prove himself to be nowhere nearly as skilled as General Washington and his fiery personality would become a serious flaw that would affect both his tactics and the United States in general.

General Anthony Wayne of the United States.

Starting in June 1777 the British would invade from Quebec into New England under the leadership of John Burgoyne and William Howe under what became known as the New England Campaign. While Howe had considered going after Philadelphia, the capital of the United States of America and current location of General Anthony Wayne, as soon as reinforcements arrived following the success of the precious winter William Howe guaranteed Burgoyne that he would be pushing north for Albany. The Campaign was intended to isolate New England and proved to be very successful. The British would succeed at defeating General Wayne and the United States became very demoralized.

After the end of the New England Campaign in the fall of 1777, General William Howe turned south to invade Pennsylvania and the Americans would only continue to lose to the British until General Howe found himself fighting in the capital of America itself, Philadelphia. On December 14th, 1777 the Americans lost their capital and the Union Jack was raised above the Philadelphia State House. By this point most of the Continental Congress had given up, the military was on the brink of revolt, and even New England, the last bastion of support for the Columbian Uprising, was demoralized after nearly a year-long blockade and siege, so the decision to finally surrender to Great Britain on December 16th, 1777 was an easy one.

The Treaty of Saratoga would be signed just a day after the USA surrendered and reintegrated the Columbian Colonies back into the Kingdom of Great Britain. However, the colonies would be punished with their former governments that had rebelled obviously being replaced. William Howe actually became the governor-general of Pennsylvania while John Burgoyne became the governor-general of New York. Massachusetts would also have to grant independence to Maine as a new colony, and the former territory of the First Vermont Republic was separated from New York as yet another colony.

The British were intent on preserving the Indian Reserve (more commonly known as the Appalachian Colony) west of the 1763 Proclamation Line, whose partition was one of the main causes of the Columbian Uprising to begin with, however, this region’s territory had been stripped away for nearly a decade by British colonial administrations, and this would continue to be the case even after the humiliation of the Columbian Colonies in 1777. William Howe’s Pennsylvania would be extended west to the border of the Province of Quebec in 1780, and under the leadership of Governor-General George Germain of Virginia quickly expanded his colony’s territorial authority in 1779 with little resistance due to the already existing Virginian influence in the region of the present-day Province of Vandalia.

The Columbian Uprising was a brief conflict that the British were destined to win, however, the consequences it had on world history were immense. In the aftermath of the war former supporters of the USA trekked west for the Spanish colony of Louisiana while others would travel to the Cape of Good Hope and became the seeds of democracy. Another significant role the Columbian Uprising played in history was the United States becoming an inspiration for the French commoners that would create the world's first great democracy.

The signatories of the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America.

Last edited:

I'm not saying that New England would necessarily surrender, the New England Campaign was an actual plan that happened in OTL, it just failed (it was called the Saratoga Campaign in OTL, too).Although I could see the South and middle colonies surrender, would New England give up so easily?

Thanks for the suggestion. I have written two timelines at the same time before and I've actually found that it helps me write better because while I'm writing one timeline I can think of ideas for the other. Either way, thanks.Be careful to not bite off more than you can chew.It would be a travesty for both of your timelines to have to be abandoned.Just some concern because I have see this happen before.

Chapter Two: The Seeds of Liberty

Chapter Two: The Seeds of Liberty

The United States of America was a short-lived experiment that had failed to achieve its goal of freedom from Great Britain, however, the legacy of the USA would continue to live on in other parts of the world. When the United States surrendered to the British much of its population fled the Columbian Colonies and became the seeds that would spread America’s democratic values.

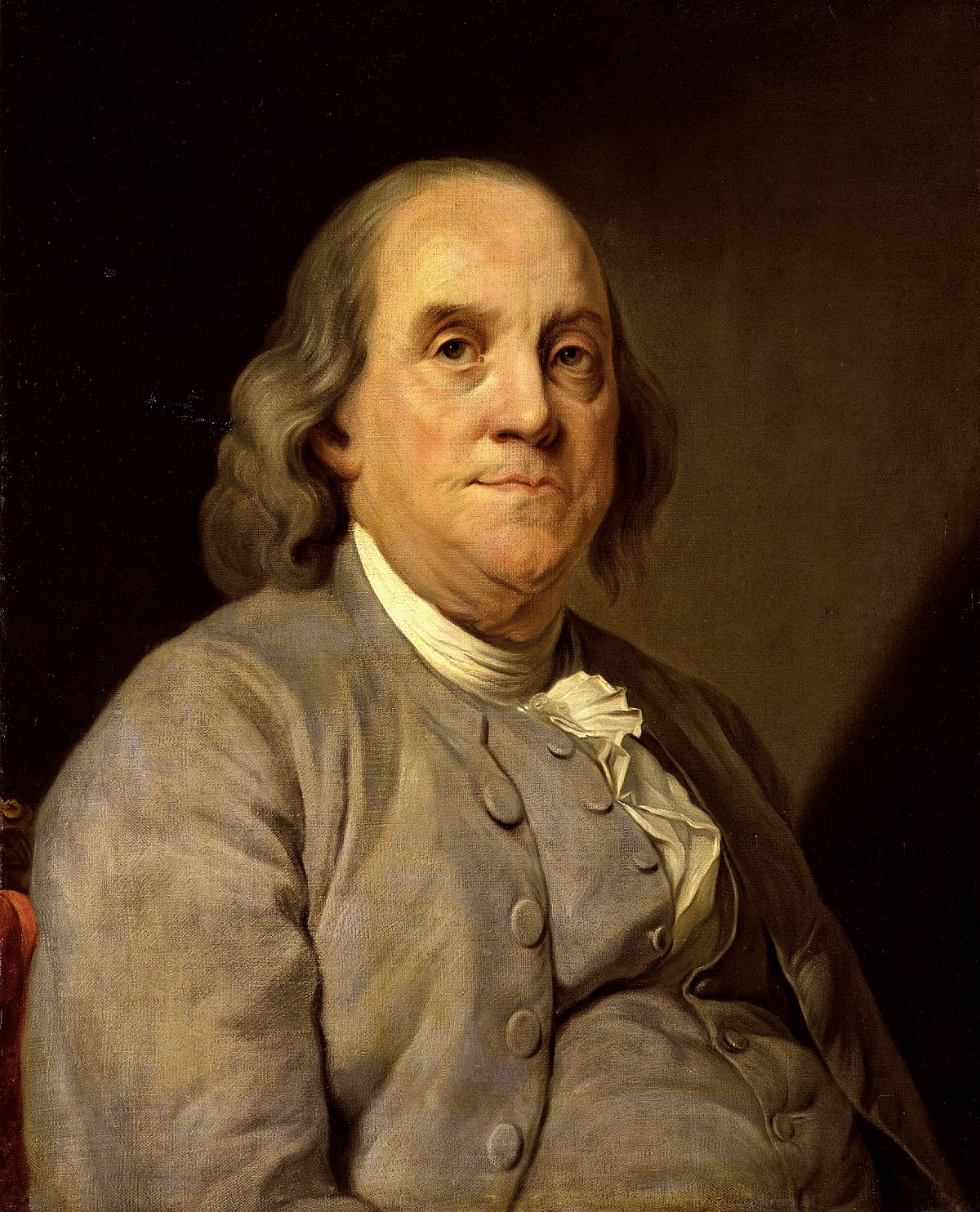

The largest concentration of Columbian revolutionaries arrived in Louisiana, a Spanish colony west of the Mississippi River. Such notable figures like Benjamin Franklin, the man who had proposed Columbian independence in the first place, and Alexander Hamilton, a senior officer who had fought in the Battle of Princeton and witnessed George Washington’s death. The Spanish actually welcomed the immigrants to colonize Louisiana as the region was barely populated (at least by Europeans), especially in the north. In early 1778 the Columbian settlers would begin to construct several new towns including New Philadelphia, which would grow into a bustling metropolis within the upcoming centuries.

New Philadelphia in the modern day including the iconic Mississippi Arch.

As the population of Louisiana grew thanks to the Columbians the colony earned a culture distinct from the rest of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. Louisianians also grew to support democracy rather than the autocratic system used by Spain and her colonies. The Louisianians disagreed with several other Spanish policies, something that would become an issue for Madrid. In order to prevent a potential disaster in the New World negotiations between Viceroy Martín de Mayorga of New Spain, King Charles III of Spain, Mayor Benjamin Franklin of New Philadelphia would take place in the September of 1779. The Spanish would create the Viceroyalty of Louisiana, which, unlike the other viceroyalties, would have a democratically elected government.

Flag of the Viceroyalty of Louisiana.

The Viceroyalty was founded on September 15th, 1779 and would hold its first election for both the viceroy and parliament on December 22nd. Several political parties would emerge to divide the population of Louisiana, however the only three significant ones were the Agrarians, Simulists, and Royalists. The Agrarian Party was created by former plantation owners from the southern Columbian Colonies who wanted Louisiana to become an agricultural-based society. This meant that the Agrarian Party also supported the practice of slavery. Agrarians were conservative and their candidate for the position of viceroy was James Madison, a young former plantation owner from Virginia.

James Madison.

The Simulist Party was another powerful group within Louisiana that preferred liberal politics. It had been founded on the idea that the people of Louisiana must find their own single identity and unite together for the common good under a strong central government. The party was supported by immigrants from North Columbia and also had a decent following among those originally from Louisiana, people of Spanish and French descent. The Simulists had selected Benjamin Franklin as their candidate and became the party of the Father of Concordia, Alexander Hamilton.

Finally there was the Royalist Party, a far-left party (at least when compared to the others) that had been mostly formed by the Spanish and French population of Louisiana. The Royalists believed that all people who called Louisiana home were equal and that the different cultures should be accepted. However, despite preaching for liberty many Royalists were opposed to the acceptance of Aboriginal Americans into Louisianian society and other members of the party owned slaves. The Royalist Party would select Francisco Bouligny, a man from the Spanish motherland, as their candidate.

Out of the three political parties the Royalists were the least likely to emerge victorious in the election because of the party being viewed as “too radical.” While the message of an agricultural society from the Agrarians was popular amongst much of Louisiana Benjamin Franklin’s charisma and former status in Pennsylvania won over the colony in the end when the December Election took place. While the Simulists did not control a majority in the parliament they would become one of the most influential parties in the Viceroyalty when Benjamin Franklin became the first viceroy.

Viceroy Benjamin Franklin of Louisiana.

Franklin’s first four-year term was defined by Louisiana’s movements towards urban development and away from the evils of slavery. Thanks to his success Viceroy Franklin would be re-elected in 1783 with a landslide majority. His second term is most well known for the partition of the unexplored land north of California (the section that is a part of Concordia is now called Cascadia) with New Spain. While the partition would never be very beneficial to either Mexico or California it would become Concordia’s sole access to the Pacific Ocean in the near future.

While Louisiana was the place most affected by Columbian rebels one can not deny the influence they had in what would one day become the Equatorial Commonwealth. Thomas Jefferson, a former Virginian, would be the man who would lead the Columbians into the Southern Hemisphere.

In the aftermath of the Columbian Uprising Jefferson was wanted by the British for treason and if he stayed in Columbia would most likely have been executed. However, Jefferson successfully escaped the clutches of Great Britain and found himself on the Cape of Good Hope (present day Riebeeckia) where he adopted the Dutch name “Thomas Jaager.” As several other former Columbian revolutionaries wound up in Africa Thomas Jaager rose to the position of a leader of some sort.

As the amount of Columbians in Riebeeckia grew and the news of success in Louisiana arrived the “Anglo-Riebeeckians” wanted their own colony to call home. The governor of the Cape Colony, Joachim van Plettenberg, encouraged exploration of the interior of South Africa and when the demand for an Anglo-Riebeeckian colony grew to a position of prominence Plettenberg saw the potential for the colony to serve as a new outpost for the Cape Colony. In November 1780 Governor Plettenberg negotiated with Thomas Jaager to establish a colony on the Atlantic coast north of the Cape of Good Hope. Starting in November 7th, 1780 the colony of Liberia was declared and construction of its capital, Nieuwe Richmond, began as Anglo-Riebeeckians poured into the colony.

Liberia would have a democratically elected government like Louisiana that one could argue was a driving inspiration for the government of Austequoria. Liberia was technically a district of the Cape Colony, however, had a large amount of autonomy. Liberia’s election for its first governor would occur on January 25th, 1781 and Thomas Jaager would win the election by a landslide.

Governor Thomas Jaager of Liberia.

Governor Jaager was quick to abolish slavery in Liberia out of fear that the young and fragile colony would otherwise collapse. Jaager also pushed towards the development of Liberia and under his reign the future cities of Atlantaburg and Bantu City were established.

While the most obvious examples of the USA’s legacy were Louisiana and Liberia other regions of the world would be influenced by the Columbians as well, such as the Radicals. However, before the Radicals entered the world stage there was the French Revolution.

The United States of America was a short-lived experiment that had failed to achieve its goal of freedom from Great Britain, however, the legacy of the USA would continue to live on in other parts of the world. When the United States surrendered to the British much of its population fled the Columbian Colonies and became the seeds that would spread America’s democratic values.

The largest concentration of Columbian revolutionaries arrived in Louisiana, a Spanish colony west of the Mississippi River. Such notable figures like Benjamin Franklin, the man who had proposed Columbian independence in the first place, and Alexander Hamilton, a senior officer who had fought in the Battle of Princeton and witnessed George Washington’s death. The Spanish actually welcomed the immigrants to colonize Louisiana as the region was barely populated (at least by Europeans), especially in the north. In early 1778 the Columbian settlers would begin to construct several new towns including New Philadelphia, which would grow into a bustling metropolis within the upcoming centuries.

New Philadelphia in the modern day including the iconic Mississippi Arch.

As the population of Louisiana grew thanks to the Columbians the colony earned a culture distinct from the rest of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. Louisianians also grew to support democracy rather than the autocratic system used by Spain and her colonies. The Louisianians disagreed with several other Spanish policies, something that would become an issue for Madrid. In order to prevent a potential disaster in the New World negotiations between Viceroy Martín de Mayorga of New Spain, King Charles III of Spain, Mayor Benjamin Franklin of New Philadelphia would take place in the September of 1779. The Spanish would create the Viceroyalty of Louisiana, which, unlike the other viceroyalties, would have a democratically elected government.

Flag of the Viceroyalty of Louisiana.

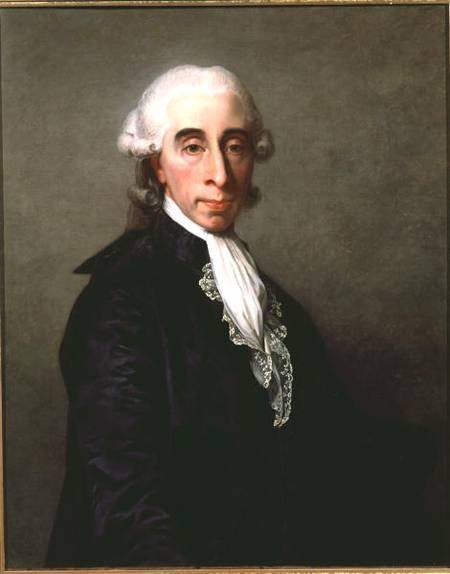

The Viceroyalty was founded on September 15th, 1779 and would hold its first election for both the viceroy and parliament on December 22nd. Several political parties would emerge to divide the population of Louisiana, however the only three significant ones were the Agrarians, Simulists, and Royalists. The Agrarian Party was created by former plantation owners from the southern Columbian Colonies who wanted Louisiana to become an agricultural-based society. This meant that the Agrarian Party also supported the practice of slavery. Agrarians were conservative and their candidate for the position of viceroy was James Madison, a young former plantation owner from Virginia.

James Madison.

The Simulist Party was another powerful group within Louisiana that preferred liberal politics. It had been founded on the idea that the people of Louisiana must find their own single identity and unite together for the common good under a strong central government. The party was supported by immigrants from North Columbia and also had a decent following among those originally from Louisiana, people of Spanish and French descent. The Simulists had selected Benjamin Franklin as their candidate and became the party of the Father of Concordia, Alexander Hamilton.

Finally there was the Royalist Party, a far-left party (at least when compared to the others) that had been mostly formed by the Spanish and French population of Louisiana. The Royalists believed that all people who called Louisiana home were equal and that the different cultures should be accepted. However, despite preaching for liberty many Royalists were opposed to the acceptance of Aboriginal Americans into Louisianian society and other members of the party owned slaves. The Royalist Party would select Francisco Bouligny, a man from the Spanish motherland, as their candidate.

Out of the three political parties the Royalists were the least likely to emerge victorious in the election because of the party being viewed as “too radical.” While the message of an agricultural society from the Agrarians was popular amongst much of Louisiana Benjamin Franklin’s charisma and former status in Pennsylvania won over the colony in the end when the December Election took place. While the Simulists did not control a majority in the parliament they would become one of the most influential parties in the Viceroyalty when Benjamin Franklin became the first viceroy.

Viceroy Benjamin Franklin of Louisiana.

Franklin’s first four-year term was defined by Louisiana’s movements towards urban development and away from the evils of slavery. Thanks to his success Viceroy Franklin would be re-elected in 1783 with a landslide majority. His second term is most well known for the partition of the unexplored land north of California (the section that is a part of Concordia is now called Cascadia) with New Spain. While the partition would never be very beneficial to either Mexico or California it would become Concordia’s sole access to the Pacific Ocean in the near future.

While Louisiana was the place most affected by Columbian rebels one can not deny the influence they had in what would one day become the Equatorial Commonwealth. Thomas Jefferson, a former Virginian, would be the man who would lead the Columbians into the Southern Hemisphere.

In the aftermath of the Columbian Uprising Jefferson was wanted by the British for treason and if he stayed in Columbia would most likely have been executed. However, Jefferson successfully escaped the clutches of Great Britain and found himself on the Cape of Good Hope (present day Riebeeckia) where he adopted the Dutch name “Thomas Jaager.” As several other former Columbian revolutionaries wound up in Africa Thomas Jaager rose to the position of a leader of some sort.

As the amount of Columbians in Riebeeckia grew and the news of success in Louisiana arrived the “Anglo-Riebeeckians” wanted their own colony to call home. The governor of the Cape Colony, Joachim van Plettenberg, encouraged exploration of the interior of South Africa and when the demand for an Anglo-Riebeeckian colony grew to a position of prominence Plettenberg saw the potential for the colony to serve as a new outpost for the Cape Colony. In November 1780 Governor Plettenberg negotiated with Thomas Jaager to establish a colony on the Atlantic coast north of the Cape of Good Hope. Starting in November 7th, 1780 the colony of Liberia was declared and construction of its capital, Nieuwe Richmond, began as Anglo-Riebeeckians poured into the colony.

Liberia would have a democratically elected government like Louisiana that one could argue was a driving inspiration for the government of Austequoria. Liberia was technically a district of the Cape Colony, however, had a large amount of autonomy. Liberia’s election for its first governor would occur on January 25th, 1781 and Thomas Jaager would win the election by a landslide.

Governor Thomas Jaager of Liberia.

Governor Jaager was quick to abolish slavery in Liberia out of fear that the young and fragile colony would otherwise collapse. Jaager also pushed towards the development of Liberia and under his reign the future cities of Atlantaburg and Bantu City were established.

While the most obvious examples of the USA’s legacy were Louisiana and Liberia other regions of the world would be influenced by the Columbians as well, such as the Radicals. However, before the Radicals entered the world stage there was the French Revolution.

Last edited:

Very interesting, you have some fun ideas regarding the fate of the American diaspora.

Two Questions:

1. How are relations between the fiercely Protestant Americans with the catholic French and Spanish in Louisiana?

2. How do the Anglo-Riebeeckians treat the various native groups living in Liberia?

Two Questions:

1. How are relations between the fiercely Protestant Americans with the catholic French and Spanish in Louisiana?

2. How do the Anglo-Riebeeckians treat the various native groups living in Liberia?

Last edited:

1: The relations between the two ethnicities is fine, partially because most Catholics live in the "Deep South" of Louisiana while the Columbians mostly live in OTL Missouri. Still, there's this fear amongst the Catholics that they'll soon be outnumbered by the Columbians.Very interesting, you have some fun ideas regarding the fate of the Armenian diaspora.

Two Questions:

1. How are relations between the fiercely Protestant Americans with the catholic French and Spanish in Louisiana?

2. How do the Anglo-Riebeeckianstreat the various native groups living in Liberia?

2: Never really put much thought into it, however, I'd guess that relations aren't horrible. There's natives being expelled from their homelands for new settlements, but on the other hand there are some natives that have chosen to adopt a western lifestyle and build their own settlements. These people are actually tolerated by Liberia because they help develop the interior. Most Liberians live around cities like the ones mentioned in the chapter so the contact of natives and the Anglo-Riebeeckians isn't too much of an issue, anyway.

Last edited:

unprincipled peter

Donor

the Columbians mostly live in OTL Missouri

hmm... a great voortrek across the wilderness of Ohio/Indiana/Illinois/Kentucky? or by ship to New Orleans and then by land up the wilderness of Louisiana/Arkansas? The mighty Mississippi was quite difficult to sail up prior to the days of steam. If it's the latter, what was the impetus for urban folk to go so far north into the wilderness instead of swamping New Orleans - Natchez - Tejas? either way, doesn't matter, they are both plausible if the writer decrees it so. The arch conjures up images of New Philadelphia being OTL's St Louis. If so, I remind you that St Louis was already founded prior.

I like it so far. my only complaint with plausibility is that it reads like Spain simply gave control over the Louisiana Territory to the Anglos as long as it remained part of Spain. Spain might make concessions, but they are going to want to maintain control.

I dislike when people ask what's going to happen next, so I'll ask it this way

The Anglos have travelled to Louisiana in both ways and the main motivation for traveling to Louisiana is that in Columbia people that sided with the USA are either criminals or can't live a successful life with the British always trying to prevent another Columbian rebel from reaching a position of prominence. I won't mention it as much because the next few chapters will focus on Europe, but yes, immigration will be a thing that will continue for the next few decades.hmm... a great voortrek across the wilderness of Ohio/Indiana/Illinois/Kentucky? or by ship to New Orleans and then by land up the wilderness of Louisiana/Arkansas? The mighty Mississippi was quite difficult to sail up prior to the days of steam. If it's the latter, what was the impetus for urban folk to go so far north into the wilderness instead of swamping New Orleans - Natchez - Tejas? either way, doesn't matter, they are both plausible if the writer decrees it so. The arch conjures up images of New Philadelphia being OTL's St Louis. If so, I remind you that St Louis was already founded prior.

I like it so far. my only complaint with plausibility is that it reads like Spain simply gave control over the Louisiana Territory to the Anglos as long as it remained part of Spain. Spain might make concessions, but they are going to want to maintain control.

I dislike when people ask what's going to happen next, so I'll ask it this way: I presume you are going to address additional immigration in future chapters? I'm guessing that only a small population of rebel Anglos flee to Louisiana (one, Spain isn't going allow a huge inflow - see above complaint about Spain losing control - and two, there isn't infrastructure to handle massive immigration all of a sudden, so prepare to see major starvation, disease, etc if tens or hundreds of thousands descend in a horde). You can't simply move the USA to LA overnight (even if Spain would allow it), so if you want LA to be a going concern, there has to be continued immigration.

As for the Spanish and colonization, I don't want to spoil anything but let's just say that Spain will be caught up in other problems so they won't be a problem.

Anyway, I'm glad you like this and think it's plausible!

unprincipled peter

Donor

well, not really plausible, but plausible enough to write a TL, and that's all that counts.

well, not really plausible, but plausible enough to write a TL, and that's all that counts.

Yeah, an actual fun timeline every now and again is a good thing to read.

Chapter Three: Viva La France!

Chapter Three: Viva La France!

When excluding the very end of the decade, the 1780s were relatively peaceful. Of course, there were minor conflicts here and there, but for the time being, it appeared as though the revolutionaries of the Age of Enlightenment that had thrown the Columbian Colonies up in arms had finally disappeared. The only notable conflict was the short lived Vermont Uprising, in which much of the young and sparsely populated colony’s population rose up against British authority in the August of 1785. The “Greencoats” of the Vermont Uprising took inspiration from the Columbian Uprising, hoping to establish an independent Republic of Vermont following the implementation of taxation laws designed to keep poor veterans of the Continental Army out of Vermont. Within a week, the minor rebellion had been suppressed, and the Province of Vermont stayed within British North America, however, the Vermont Tax was repealed a few weeks later.

At first the 1780s were seen as a new beginning for the Kingdom of France, which had been severely weakened after the Seven Years War and was on the brink of a seemingly inevitable economic collapse. By the time the Columbian Uprising came and went, it appeared as though French economic recovery was possible. If the right people were in the right place at the right time then maybe, just maybe, France could return to its position as one of Europe’s greatest empires and potential usurper of global British hegemony. Excited by the possibility of a rebirth in French power, the Duke of Aiguillon, the former French Secretary of State for War, envisioned the establishment of a new French colonial empire spanning the Indian Ocean. Hoping to regain the prestige he had lost due to his incompetence as a statesman, the Duke of Aiguillon came to King Louis XVI of France, hoping to get the funding necessary to go on an expedition to seek out potential colonial outposts in the Indian Ocean. Louis XVI, whose wife’s dispute with the Duke of Aiguillon had forced the Duke out of the French government to begin with, refused to fund these endeavors, which would cause him to turn to Prince Charles, Louis XVI’s brother.

Charles, a power-hungry man described as being “more royalist than the king,” agreed to fund the Duke of Aiguillon’s expedition for three years, under the condition that if a colony was established, Prince Charles would be given some authority over colonial governance. The Duke of Aiguillon graciously accepted Charles’ conditions, and King Louis XVI, who was happy to endorse the plan as long as it did not cost him anything, agreed to recognize any colony established by the Aiguillon Expedition. And so, in the March of 1784, the Duke of Aiguillon and a sizeable fleet left France for the Indian Ocean, arriving a few months later along the coast of Madagascar. From here, Aiguillon’s fleet charted out the coast of eastern Africa, southern Arabia, and the East Indies before ultimately arriving in northern Australasia (then referred to in its entirety as New Holland before the establishment of the Dutch colony that shares its namesake).

Believing that Australasia, whose natives still adhered to tribal civilizations, would not only serve as an ideal trading post but would also be easy to conquer, the Duke of Aiguillon would return to France in the January of 1785 to detail his discoveries. While both King Louis XVI and Prince Charles were sceptical of establishing a colony on such a barren landmass, the Duke of Aiguillon did emphasize his discovery of more suitable land for colony development in southern Australasia, and argued that a hypothetical Australasian colony would operate as a “French Cape Colony,” with the colony primarily sustaining itself via trade and commerce. To the Duke of Aiguillon’s pleasure, Louis and Charles would approve of developing an Australasian colony, and the Colony of New Occitania was declared on March 29th, 1785.

While the Kingdom of France would claim all of the Australasian mainland for itself, New Occitania only extended across the western sect of Australasia, and even then legitimate French authority in New Occitania was limited to small coastal settlements. Nonetheless, the colony was a source of pride for France, especially Prince Charles, who was the sole owner of the colony before forming the New Occitan Company (NCO) in 1786 and transferring control of the colony to said company, which Charles was the leader of. The NCO would eventually build up its own armed forces, which the elderly Duke of Aiguillon was put in charge of. As the leader of the NCO’s military, Aiguillon returned to a position of prestige, and would win more respect from Charles when he conquered territory occupied by the Noongar people in southern New Occitania, where the new colonial capital, New Toulouse began construction following the brief Noongar War of the September of 1787.

Painting of New Toulouse, circa 1790.

While New Occitania proved that it would one day become a successful colony, France would soon plunge into chaos. The broken economy that had existed since the Seven Years War had finally caught up to the Kingdom of France, thus shattering any hopes that a new French global hegemony was on the rise. France would try to solve the financial crisis by altering the tax system, however, this proved to be ineffective. France would also find problems in the Estate-General, a governing body that had last met in 1614 that consisted of three estates. The first represented the clergy, the second represented the aristocrats, and the third (and weakest) represented the commoners.

The Third Estate was irritated with its position and many, such as Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, argued for the importance of the commoners and how they were destined for greater significance in the French government. It would be the middle class that would ignite the flames of the French Revolution. Alongside the Third Estate, they would form the National Assembly as an assembly of the masses of France. As King Louis XVI began to become an enemy of the assembly, members would meet in a tennis court in Versailles where they would swear the Tennis Court Oath on June 20th, 1789, under which they agreed to not separate until France had a constitution.

The Tennis Court Oath.

The majority of representatives of the clergy would soon join the Third Estate, along with 47 members of the nobility. After Jacques Necker, the unpopular Comptroller-General was fired in July 1789, Parisians jumped to the conclusion that the Assembly was the king’s next target and began an open rebellion. The mobs eventually gained the support of some of the French Guard and turned their attention to the weapons and ammunition inside the Bastille fortress. On July 14th, 1789, the Storming of the Bastille would occur, and after several hours of combat those guarding the Bastille surrendered and their leader, Bernard-René de Launay, was held hostage by the mobs. King Louis XVI was alarmed by the Storming of the Bastille, and would back down for the time being. Jean-Sylvain Bailly, the former president of the Assembly during the time of the Tennis Court Oath, would become the new mayor of France under a governmental structure known as a Commune. On July 17th, 1789, the king visited Paris where he accepted a tricolore cockade, a symbol of the emerging French democracy, to the celebration of his people.

King Louis XVI’s visit to Paris was a turning point for the French quest for democracy and the National Constituent Assembly (the successor to the National Assembly) eventually became the new governing body of France, on par with the king. The Assembly had decided that if the king accepted a new constitution then he would be allowed to stay on the throne. With the approval of the monarchy, France’s new constitution would begin to be written in 1791, and following the ratification of said constitution on September 3rd, 1791 France became the world’s first democratic sovereign state, named the Roturier Kingdom of France.

Flag of the Roturier Kingdom of France.

Upon arriving in Paris to write the constitution of what would become the Roturier Kingdom of France, the delegates of the Convention of Versailles (named after the French monarchy’s residence, where the Convention was held) were tasked with creating a system of governance that would appease both liberal republicans and conservative monarchists alike. The pamphlet, “What is the Third Estate?” by Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, which advocated in favor of the abolition of the First and Second Estates, became the basis for the French constitution, which sought out the establishment of a representative democracy. From here, questions about the balance between the people and aristocracy would begin to become the center of attention in Versailles, while the French people celebrated the ideals of popular sovereignty in the meantime, building up militias in the countryside.

The debate over the French constitution would eventually cause inspiration to be derived from the system of governance of the ancient Roman Republic. Numerous liberals had turned to the Roman Republic for designing the French constitution, with the French electoral process being based heavily off of that of the Roman Republic. Perhaps the most influential document that led to creation of the government of the Roturier Kingdom of France was a pamphlet named The Rights of the Plebeian. Written by the Marquis de Lafayette, a young veteran of the Continental Army who had turned to the Roman Republic as a source of inspiration for his egalitarian ambitions after the United States of America was crushed, with help from a handful of prominent French Enlightenment philosophers, the Rights of the Plebeian revolved around the idea that after the collapse of the ancient Roman Empire, the two classes of Roman society, the Plebeian and the Patrician, had not disappeared. Instead, Lafayette claimed that the Roman classes had just taken new forms, from serfs and lords to slaves and masters.

Marquis de Lafayette argued that the system of the Roman Republic must be reinstituted, however, this time Plebeian class would control the Republic rather than the Patricians. Only then would the masses control their government and the Plebeian would be liberated in the name of equality. This mindset, which was championed by liberals, and reluctantly supported by a few monarchists, who believed that the reinstitution of Roman republicanism would ensure strong centralization, would become the basis for the Roturier Kingdom of France. From here, the French legislative branch was modeled after the Roman senate, with members being appointed by the consul, the elected French head of government. In order to mimic the dual consulship of the Roman Republic, the French monarchy would play the role of the second consul, however, in order to ensure that popular sovereignty would be put in place, the monarch of France could only nominate people to the Senate of the Roturier Kingdom of France, and could not appoint them.

The French constitution would also re-establish the ancient Roman positions of the magistrates to replace the institutions of secretaries. No new magistrates were expected to be created as France changed overtime, however, each magistrate presided over broad issues and could establish smaller bodies under their jurisdiction to focus on specific issues. These positions were elected by the Plebeian Tribune, which was modeled after the ancient tribunes of Rome, but took on the role of the Centuriate Assembly, as well as the Tribal Assembly, which were merged into a single unicameral legislative body. The Tribune would hold the ability to propose legislation to the consulship (something the Senate was also capable of doing), which would need to approve of any proposed bills.

After several revisions and debates, the constitution of the Roturier Kingdom of France was finally put into place, thus initiating the beginning of French democracy, and the ideals of the constitution would become the basis for a new political ideology. The concept of a Plebeian-Patrician class struggle that would be solved via the institution of a populist Roman Republic-esque government was deemed “communism” (named after the communes that had served as the basis of the National Constituent Assembly), as outlined by the Communist Manifesto, written by Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and Marquis de Lafayette, who would become the first censor and praetor of the Roturier Kingdom of France respectively after being assigned the duty of writing a manifesto that would outline the ideological developments of the Versailles Convention.

Censor Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès of the Roturier Kingdom of France, who is typically credited as one of the two founders of communism alongside Marquis de Lafayette.

The Roturier Kingdom of France was not only revolutionary for the creation of communism, an ideology that would define the Age of Enlightenment and much of the history of 19th Century, but was also extremely progressive for the time period for the abolition of serfdom, feudalism, and rights for the nobility. Furthermore, several rights that had never been joined by anyone other than the aristocracy of the world were suddenly guaranteed to all French citizens, and even women, who were not yet guaranteed the right to vote in France, enjoyed limited rights, such as the freedom of speech.

As the members of the Plebeian Tribune (MT) were elected throughout the fall of 1791, political parties began to form in France, and partisanship, something only really seen in Louisiana and Liberia thus far, would become the norm of French politics. The parties within France were inherited from the former National Constituent Assembly, being the conservative Right Party (interestingly enough, the term “right-wing” and “left-wing” originated from the French Revolution, with those who supported the monarchy sitting on the right side of the Estates General, and those opposing the monarchy sitting on the left side), the Democratic-Royalists, who usually sided with the French aristocracy, and finally the National Party, which had liberal tendencies. The Democratic Royalists and Nationals would prove to be the two strongest parties in the election, however in the end the Democratic-Royalist candidate Pierre Victor stood no chance against against the National Jean-Sylvain Bailly whose policies of equality and democracy while still having some conservative views allowed him to become the first consul of France on January 25th, 1792.

Consul Jean-Sylvain Bailly of France.

While most in France celebrated the declaration of the Roturier Kingdom there were a few, mostly aristocrats, who feared the path the new democratic regime may take. The most notable opponent was Prince Charles, the ruler of New Occitania, who had actually been in New Toulouse to visit his growing colony when the Roturier Kingdom of France was created. Upon returning to France in the November of 1791, Charles became the de facto leader of those opposed to the communist government, a cabal of reactionaries and monarchists, with this group being deemed the Restorationist Club. They believed that it was the aristocracy’s God-given right to rule France. The Restorationist Club also wanted revenge on the British for the Seven Years War and believed that the communists would only weaken any hypothetical war effort against Great Britain.

Charles eventually came to the conclusion that if the communist reign over France was to be destroyed then the Restorationists must overthrow the Roturier Kingdom of France and the increasingly liberal King Louis XVI with force. Therefore, on April 19th, 1792 the Restorationists would conquer the city of Nantes via paramilitary force with aid from the NCO, and declared the French Empire, of which Charles was crowned Emperor Charles I. More Restorationists would rise up against the communists, and primarily occupied northwestern France, which would spark a conflict between the forces of revolution and reactionism, the first French Civil War.

When excluding the very end of the decade, the 1780s were relatively peaceful. Of course, there were minor conflicts here and there, but for the time being, it appeared as though the revolutionaries of the Age of Enlightenment that had thrown the Columbian Colonies up in arms had finally disappeared. The only notable conflict was the short lived Vermont Uprising, in which much of the young and sparsely populated colony’s population rose up against British authority in the August of 1785. The “Greencoats” of the Vermont Uprising took inspiration from the Columbian Uprising, hoping to establish an independent Republic of Vermont following the implementation of taxation laws designed to keep poor veterans of the Continental Army out of Vermont. Within a week, the minor rebellion had been suppressed, and the Province of Vermont stayed within British North America, however, the Vermont Tax was repealed a few weeks later.

At first the 1780s were seen as a new beginning for the Kingdom of France, which had been severely weakened after the Seven Years War and was on the brink of a seemingly inevitable economic collapse. By the time the Columbian Uprising came and went, it appeared as though French economic recovery was possible. If the right people were in the right place at the right time then maybe, just maybe, France could return to its position as one of Europe’s greatest empires and potential usurper of global British hegemony. Excited by the possibility of a rebirth in French power, the Duke of Aiguillon, the former French Secretary of State for War, envisioned the establishment of a new French colonial empire spanning the Indian Ocean. Hoping to regain the prestige he had lost due to his incompetence as a statesman, the Duke of Aiguillon came to King Louis XVI of France, hoping to get the funding necessary to go on an expedition to seek out potential colonial outposts in the Indian Ocean. Louis XVI, whose wife’s dispute with the Duke of Aiguillon had forced the Duke out of the French government to begin with, refused to fund these endeavors, which would cause him to turn to Prince Charles, Louis XVI’s brother.

Charles, a power-hungry man described as being “more royalist than the king,” agreed to fund the Duke of Aiguillon’s expedition for three years, under the condition that if a colony was established, Prince Charles would be given some authority over colonial governance. The Duke of Aiguillon graciously accepted Charles’ conditions, and King Louis XVI, who was happy to endorse the plan as long as it did not cost him anything, agreed to recognize any colony established by the Aiguillon Expedition. And so, in the March of 1784, the Duke of Aiguillon and a sizeable fleet left France for the Indian Ocean, arriving a few months later along the coast of Madagascar. From here, Aiguillon’s fleet charted out the coast of eastern Africa, southern Arabia, and the East Indies before ultimately arriving in northern Australasia (then referred to in its entirety as New Holland before the establishment of the Dutch colony that shares its namesake).

Believing that Australasia, whose natives still adhered to tribal civilizations, would not only serve as an ideal trading post but would also be easy to conquer, the Duke of Aiguillon would return to France in the January of 1785 to detail his discoveries. While both King Louis XVI and Prince Charles were sceptical of establishing a colony on such a barren landmass, the Duke of Aiguillon did emphasize his discovery of more suitable land for colony development in southern Australasia, and argued that a hypothetical Australasian colony would operate as a “French Cape Colony,” with the colony primarily sustaining itself via trade and commerce. To the Duke of Aiguillon’s pleasure, Louis and Charles would approve of developing an Australasian colony, and the Colony of New Occitania was declared on March 29th, 1785.

While the Kingdom of France would claim all of the Australasian mainland for itself, New Occitania only extended across the western sect of Australasia, and even then legitimate French authority in New Occitania was limited to small coastal settlements. Nonetheless, the colony was a source of pride for France, especially Prince Charles, who was the sole owner of the colony before forming the New Occitan Company (NCO) in 1786 and transferring control of the colony to said company, which Charles was the leader of. The NCO would eventually build up its own armed forces, which the elderly Duke of Aiguillon was put in charge of. As the leader of the NCO’s military, Aiguillon returned to a position of prestige, and would win more respect from Charles when he conquered territory occupied by the Noongar people in southern New Occitania, where the new colonial capital, New Toulouse began construction following the brief Noongar War of the September of 1787.

Painting of New Toulouse, circa 1790.

While New Occitania proved that it would one day become a successful colony, France would soon plunge into chaos. The broken economy that had existed since the Seven Years War had finally caught up to the Kingdom of France, thus shattering any hopes that a new French global hegemony was on the rise. France would try to solve the financial crisis by altering the tax system, however, this proved to be ineffective. France would also find problems in the Estate-General, a governing body that had last met in 1614 that consisted of three estates. The first represented the clergy, the second represented the aristocrats, and the third (and weakest) represented the commoners.

The Third Estate was irritated with its position and many, such as Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, argued for the importance of the commoners and how they were destined for greater significance in the French government. It would be the middle class that would ignite the flames of the French Revolution. Alongside the Third Estate, they would form the National Assembly as an assembly of the masses of France. As King Louis XVI began to become an enemy of the assembly, members would meet in a tennis court in Versailles where they would swear the Tennis Court Oath on June 20th, 1789, under which they agreed to not separate until France had a constitution.

The Tennis Court Oath.

The majority of representatives of the clergy would soon join the Third Estate, along with 47 members of the nobility. After Jacques Necker, the unpopular Comptroller-General was fired in July 1789, Parisians jumped to the conclusion that the Assembly was the king’s next target and began an open rebellion. The mobs eventually gained the support of some of the French Guard and turned their attention to the weapons and ammunition inside the Bastille fortress. On July 14th, 1789, the Storming of the Bastille would occur, and after several hours of combat those guarding the Bastille surrendered and their leader, Bernard-René de Launay, was held hostage by the mobs. King Louis XVI was alarmed by the Storming of the Bastille, and would back down for the time being. Jean-Sylvain Bailly, the former president of the Assembly during the time of the Tennis Court Oath, would become the new mayor of France under a governmental structure known as a Commune. On July 17th, 1789, the king visited Paris where he accepted a tricolore cockade, a symbol of the emerging French democracy, to the celebration of his people.

King Louis XVI’s visit to Paris was a turning point for the French quest for democracy and the National Constituent Assembly (the successor to the National Assembly) eventually became the new governing body of France, on par with the king. The Assembly had decided that if the king accepted a new constitution then he would be allowed to stay on the throne. With the approval of the monarchy, France’s new constitution would begin to be written in 1791, and following the ratification of said constitution on September 3rd, 1791 France became the world’s first democratic sovereign state, named the Roturier Kingdom of France.

Flag of the Roturier Kingdom of France.

Upon arriving in Paris to write the constitution of what would become the Roturier Kingdom of France, the delegates of the Convention of Versailles (named after the French monarchy’s residence, where the Convention was held) were tasked with creating a system of governance that would appease both liberal republicans and conservative monarchists alike. The pamphlet, “What is the Third Estate?” by Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, which advocated in favor of the abolition of the First and Second Estates, became the basis for the French constitution, which sought out the establishment of a representative democracy. From here, questions about the balance between the people and aristocracy would begin to become the center of attention in Versailles, while the French people celebrated the ideals of popular sovereignty in the meantime, building up militias in the countryside.

The debate over the French constitution would eventually cause inspiration to be derived from the system of governance of the ancient Roman Republic. Numerous liberals had turned to the Roman Republic for designing the French constitution, with the French electoral process being based heavily off of that of the Roman Republic. Perhaps the most influential document that led to creation of the government of the Roturier Kingdom of France was a pamphlet named The Rights of the Plebeian. Written by the Marquis de Lafayette, a young veteran of the Continental Army who had turned to the Roman Republic as a source of inspiration for his egalitarian ambitions after the United States of America was crushed, with help from a handful of prominent French Enlightenment philosophers, the Rights of the Plebeian revolved around the idea that after the collapse of the ancient Roman Empire, the two classes of Roman society, the Plebeian and the Patrician, had not disappeared. Instead, Lafayette claimed that the Roman classes had just taken new forms, from serfs and lords to slaves and masters.

Marquis de Lafayette argued that the system of the Roman Republic must be reinstituted, however, this time Plebeian class would control the Republic rather than the Patricians. Only then would the masses control their government and the Plebeian would be liberated in the name of equality. This mindset, which was championed by liberals, and reluctantly supported by a few monarchists, who believed that the reinstitution of Roman republicanism would ensure strong centralization, would become the basis for the Roturier Kingdom of France. From here, the French legislative branch was modeled after the Roman senate, with members being appointed by the consul, the elected French head of government. In order to mimic the dual consulship of the Roman Republic, the French monarchy would play the role of the second consul, however, in order to ensure that popular sovereignty would be put in place, the monarch of France could only nominate people to the Senate of the Roturier Kingdom of France, and could not appoint them.

The French constitution would also re-establish the ancient Roman positions of the magistrates to replace the institutions of secretaries. No new magistrates were expected to be created as France changed overtime, however, each magistrate presided over broad issues and could establish smaller bodies under their jurisdiction to focus on specific issues. These positions were elected by the Plebeian Tribune, which was modeled after the ancient tribunes of Rome, but took on the role of the Centuriate Assembly, as well as the Tribal Assembly, which were merged into a single unicameral legislative body. The Tribune would hold the ability to propose legislation to the consulship (something the Senate was also capable of doing), which would need to approve of any proposed bills.

After several revisions and debates, the constitution of the Roturier Kingdom of France was finally put into place, thus initiating the beginning of French democracy, and the ideals of the constitution would become the basis for a new political ideology. The concept of a Plebeian-Patrician class struggle that would be solved via the institution of a populist Roman Republic-esque government was deemed “communism” (named after the communes that had served as the basis of the National Constituent Assembly), as outlined by the Communist Manifesto, written by Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and Marquis de Lafayette, who would become the first censor and praetor of the Roturier Kingdom of France respectively after being assigned the duty of writing a manifesto that would outline the ideological developments of the Versailles Convention.

Censor Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès of the Roturier Kingdom of France, who is typically credited as one of the two founders of communism alongside Marquis de Lafayette.

The Roturier Kingdom of France was not only revolutionary for the creation of communism, an ideology that would define the Age of Enlightenment and much of the history of 19th Century, but was also extremely progressive for the time period for the abolition of serfdom, feudalism, and rights for the nobility. Furthermore, several rights that had never been joined by anyone other than the aristocracy of the world were suddenly guaranteed to all French citizens, and even women, who were not yet guaranteed the right to vote in France, enjoyed limited rights, such as the freedom of speech.

As the members of the Plebeian Tribune (MT) were elected throughout the fall of 1791, political parties began to form in France, and partisanship, something only really seen in Louisiana and Liberia thus far, would become the norm of French politics. The parties within France were inherited from the former National Constituent Assembly, being the conservative Right Party (interestingly enough, the term “right-wing” and “left-wing” originated from the French Revolution, with those who supported the monarchy sitting on the right side of the Estates General, and those opposing the monarchy sitting on the left side), the Democratic-Royalists, who usually sided with the French aristocracy, and finally the National Party, which had liberal tendencies. The Democratic Royalists and Nationals would prove to be the two strongest parties in the election, however in the end the Democratic-Royalist candidate Pierre Victor stood no chance against against the National Jean-Sylvain Bailly whose policies of equality and democracy while still having some conservative views allowed him to become the first consul of France on January 25th, 1792.

Consul Jean-Sylvain Bailly of France.

While most in France celebrated the declaration of the Roturier Kingdom there were a few, mostly aristocrats, who feared the path the new democratic regime may take. The most notable opponent was Prince Charles, the ruler of New Occitania, who had actually been in New Toulouse to visit his growing colony when the Roturier Kingdom of France was created. Upon returning to France in the November of 1791, Charles became the de facto leader of those opposed to the communist government, a cabal of reactionaries and monarchists, with this group being deemed the Restorationist Club. They believed that it was the aristocracy’s God-given right to rule France. The Restorationist Club also wanted revenge on the British for the Seven Years War and believed that the communists would only weaken any hypothetical war effort against Great Britain.

Charles eventually came to the conclusion that if the communist reign over France was to be destroyed then the Restorationists must overthrow the Roturier Kingdom of France and the increasingly liberal King Louis XVI with force. Therefore, on April 19th, 1792 the Restorationists would conquer the city of Nantes via paramilitary force with aid from the NCO, and declared the French Empire, of which Charles was crowned Emperor Charles I. More Restorationists would rise up against the communists, and primarily occupied northwestern France, which would spark a conflict between the forces of revolution and reactionism, the first French Civil War.

Last edited:

World Map Circa 1791

Here's the world map in 1791. Not a lot has changed when compared to our timeline, excluding the obvious lack of the USA. Hopefully you enjoyed this last chapter and will like the upcoming chapters which is when the timeline will really start to get unique!

Last edited:

The first French civil war, interesting. I would bet my money on the Communists, as Charles and the nobels historically were rather incompetent, though they may be given some foreign support.

Threadmarks

View all 68 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Jeremy Bentham Wiki Infobox Chapter Thirty-Two: A House Divided Map of the United Dominion of Riebeeckia Circa 1859 Riebeeckian chancellery election 1859 Chapter Thirty-Three: The Shot Heard Around the World United Dominion of Riebeeckia Wiki Infobox Chapter Thirty-Four: Revolution and Reaction Map of the Mutapa Empire Circa September 1860

Share: