You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dreams of Liberty: A Failure at Princeton

- Thread starter ETGalaxy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 68 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

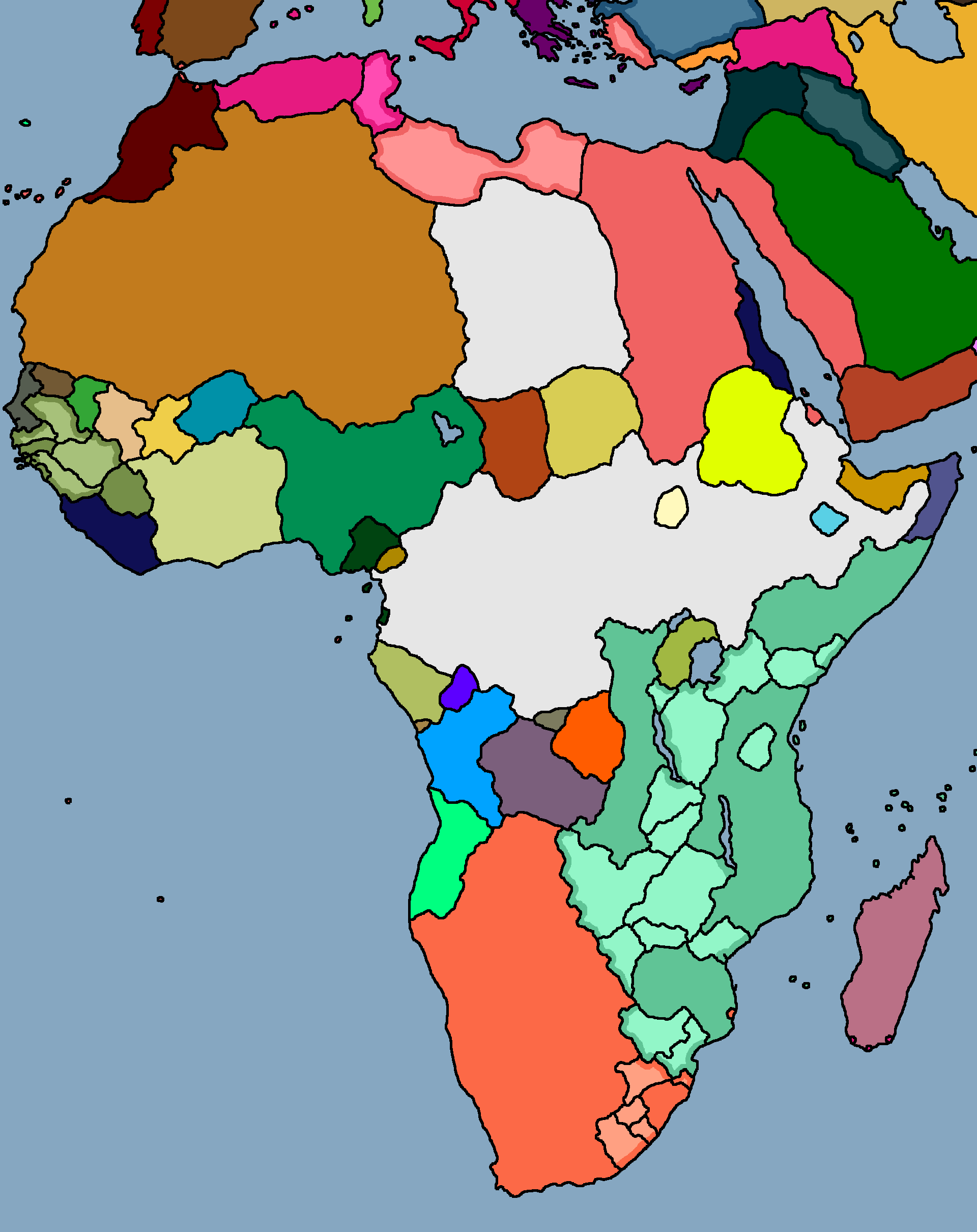

Jeremy Bentham Wiki Infobox Chapter Thirty-Two: A House Divided Map of the United Dominion of Riebeeckia Circa 1859 Riebeeckian chancellery election 1859 Chapter Thirty-Three: The Shot Heard Around the World United Dominion of Riebeeckia Wiki Infobox Chapter Thirty-Four: Revolution and Reaction Map of the Mutapa Empire Circa September 1860I probably can’t do a would map because that would take ages, but if there’s a specific region you’re interested in, I’m happy to do a map of that area.Just wondering, but could a version of the map with the countries labelled below with the colors they represent be added? Just that it's a bit hard to guess what country is what color.

Chapter Twenty-Eight: The Decade of Despair

Chapter Twenty-Eight: The Decade of Despair

As any writer of speculative fiction would tell you, history is often driven by seemingly unimportant moments that cascade into major world-reaching events. To an extent, this was the origin of the Decade of Despair. The origins of this economic and political calamity can be traced back to the War of Malacca, which, despite being notorious in the present day due to the increased influence of its belligerents later on into history, was a more or less ignored conflict outside of Southeast Asia and the Hanoverian Realms. Even those who lived in Germania, a nation that was actively fighting in the War of Malacca, did not care much for a conflict that was very remote to anyone who was not actively participating in the relatively small war effort. To the residents of Hanover and Amsterdam, the War of Malacca was yet another distant war in the name of Germania’s empire that had more or less no effect on their daily lives. To the residents of nations completely uninvolved in the War of Malacca, the conflict was a distant footnote in newspapers, only passionately followed by enthusiasts and ministers who anticipated the brewing of storm clouds from the effect that the constant military defeats in the East Indies had on one of the globe’s most influential economic forces.

As the War of Malacca came to an end and soldiers from Riebeeckia settled back into their lifestyles away from the frontlines of the Malay Archipelago, these storm clouds began to form. The War of Malacca was a decisive victory for the Hanoverian Realms, but the victors had nonetheless taken a toll in a conflict the likes of which the loyal forces of Empress Victoria had not faced since the War of Indian Unification. Furthermore, the War of Malacca had been no easy victory. If the Burmese had managed to secure the quick offensive throughout the East Indies that they had attempted in the initial phases of the War of Malacca, the end result of the clash would have likely gone in favor of the Konbaung Dynasty. Regardless, the numerous battles fought throughout the Malay Archipelago left the Hanoverian East India Company’s most profitable colony, Hannoveraner Malaiisch, in an economically awkward position due to much of the infrastructure that the colony depended on, such as well-kept ports and bureaucratic headquarters, being devastated by the War of Malacca.

This time of financial instability hit the HOK at a time when it needed to make money more than ever. The company’s private armed forces had played an important role in the War of Malacca, and financing a war effort is, of course, an expensive endeavor. Following the Treaty of Calcutta, the HOK found itself in deep debt and unable to pay both employers and its military. Total collapse of the HOK was avoided in the short term via wealthy investors and bailouts from the Germanian government, however, these were investments that the stalling company simply could not pay back, thus meaning that the money was often lost altogether. Once the HOK’s charter expired in October 1852, the company was effectively bankrupt and subsequently dissolved on October 5th. The colonial holdings of the HOK were seized by the Germanic Empire, with their fate to be decided at a later date, but as news of the collapse hit the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, the center of the markets of the Hanoverian Realms, panic set in. Stocks quickly became worthless and the ripple effect of the heavy loss of investments into the HOK spread out across the entirety of the stock exchange, thus causing a gradual recession. This recession ultimately resulted in a stock market crash over the course of October of 1852, which snowballed into bank failures, deflation, and general bankruptcy. All of this contributed to the Great Crisis of 1852, the largest depression the global economy had faced since the General Crisis of 1640.

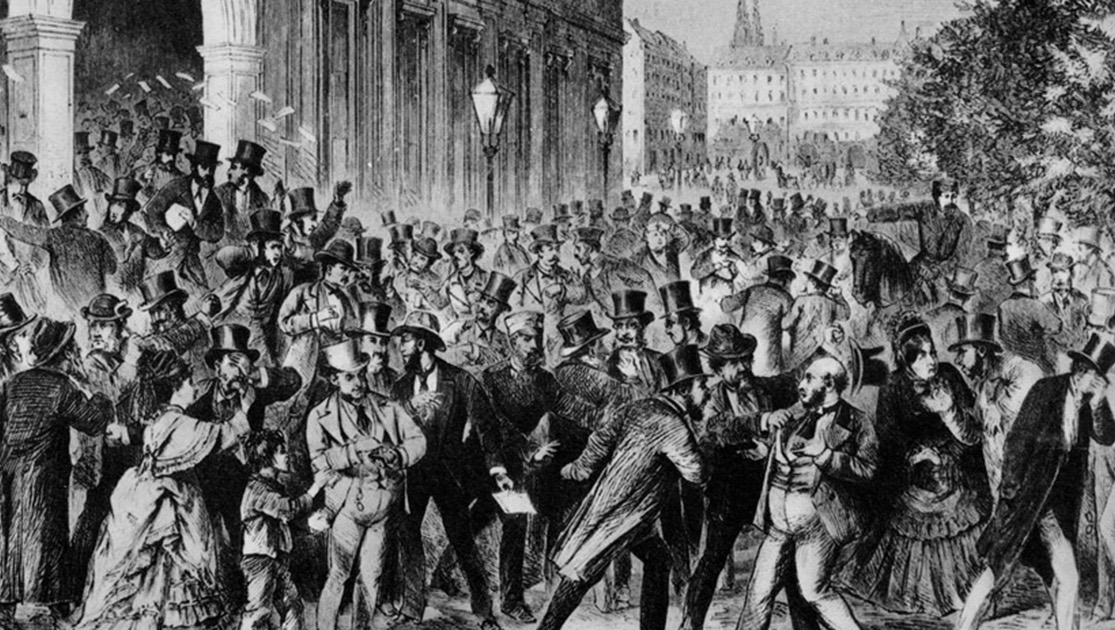

Panic outside the Bank of Amsterdam during the Great Crisis of 1852.

While the Great Crisis had immediate economic impacts on the Hanoverian Realms, whose economies quickly collapsed and unemployment rates skyrocketed, it would gradually lead to the downfall of neighboring markets across Europe within the following months. The effects of the Great Crisis would later spread across the planet to nations tied to Europe’s economy in one way or another, however, it was in these nations that the Great Crisis had varying degrees of social impact. In the states of the Columbian Coast, whose international economies were tightly strung to those of Europe, the effect of the Crisis in the powers of this region, such as Columbia and Virginia, were comparable to the effects felt back across the Atlantic. Conversely, in the mostly autarkic Bogota Sphere, the Great Crisis caused a brief and subtle recession and a decline in access to shattered European markets at most. In Africa, where coastal states were still building up industrialized and globalized economies that had yet to be completely strung into the chaotic complexities of 19th Century international capitalism, the effects of the Great Crisis of 1852 were felt even less.

But back in the Germanic Empire, one of the largest and most powerful economies both in Europe and abroad, the impact of a stock market crash of domestic origins was catastrophic. Unemployment rates would skyrocket, and as the people of Germania grimly welcomed in the new year, national unemployment rates exceded twenty-five percent. Backlash against the Imperial government’s response was soon felt by the Bundesrat, which was harshly criticized for bailing out the HOK. To prevent backlash from being targeted at the Germanian nobility, Empress Victoria would demand the resignation of the Minister of Finance from her cabinet and, more importantly, would call for a general election within the House of Commons to take place on November 1st, 1852. Likewise, numerous nobles of the internal kingdoms of the Germanic Empire saw the writing on the wall and followed suit by replacing their electors to the House of Lords.

The general election of 1852 would be the first time in Germania’s history under the constitution of 1833 that the ruling Imperial Union Party (PKU) faced a threat of being removed from power. Forged in 1833 by wealthy conservative statesmen from across Germania as a way to maintain their grip on power under the constraints of the new Germanian constitution. As property owning men, the class that had formed the PKU to begin with, were the only class capable of voting within the Germanic Empire, the PKU maintained a monopoly on political authority within the Bundesrat throughout much of its early history, often finding itself to be the sole party within the Bundesrat at all. However, as populism swept the world throughout the 1840s, the PKU would face legitimate opposition for the first time in its history as the Tuisto Party (TP) began to quickly acquire seats. Originally formed in 1834 as a collection of liberal Germanian statesmen who supported increasing popular sovereignty, increasing individual rights, and establishing a distinct Germanian national identity influenced by ancient Germanic culture, the TP had since become a populist party that had extended its manifesto to improve working conditions, limit gender inequality, and regulate the powers of Germania’s financial aristocracy.

Following the 1845 general election, the Tuisto Party secured enough seats within the House of Commons to effectively form Her Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition, even if its membership was vastly outnumbered by that of the PKU. Through skillful negotiation mixed with movements to get the public on its side, the TP managed to pass an amendment to the Germanian constitution through the PKU-controlled Bundesrat in 1847 that gave suffrage to all men at least twenty-one years of age, regardless of whether or not they held property. The massive expansion of suffrage within the Germanic Empire prompted the subsequent 1847 Germanian general election in which, alongside the entry of an assortment of other minor parties into the House of Commons, the TP extended its numbers at the expense of the PKU’s, with the two parties’ numbers being much more comparable in the aftermath. Therefore, as a party with growing public support, a message of massive populist societal reform that would undo the mistakes that led to the Great Crisis, and general disdain for the failures of the ruling party, the Tuisto Party was in an excellent position going into the 1852 general election. Surely enough, on the morning of November 2nd, 1852 Germanian newspapers reported on a sweeping Tuisto victory within the House of Commons, thus meaning that Heinrich von Gagern, once deemed a radical by the rulers of the Bundesrat, was now the Speaker of the House of Commons and therefore the most powerful democratically elected official in all of Germania.

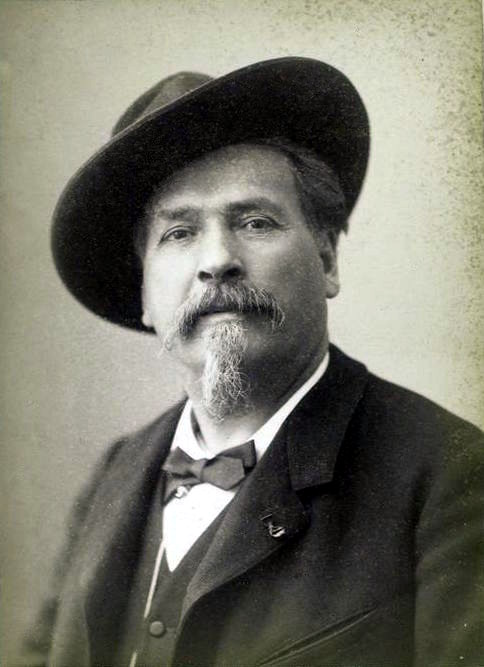

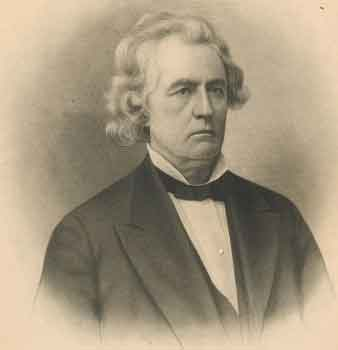

Speaker of the House of Commons Heinrich von Gagern of the Germanic Empire.

While the speakership was a position that technically held little power, with Gagern’s official role within the House being to preside over its sessions and ensure that they were carried out in an orderly fashion, Gagern was also the leader of the Tuisto Party within the House of Commons and therefore the party’s de facto political leader overall. Once the new legislature was officially assembled on November 21st, 1852, Speaker Gagern would set out to push his populist legislation through both houses of the Bundesrat and the empress, starting with the first progressive income tax in Germanian history. In order to pass such a bill, as well as similarly progressive legislation, Heinrich von Gagern sought to get close to Empress Victoria by often meeting with Her Majesty as a way to persuade her to support his agenda. In regards to the conservatives of both the House of Lords and the Germanian cabinet, Gagern became notorious for arranging private meetings with these individuals to make dealings behind the scenes of open political debate and maneuvering. Gagern also made good use of depicting himself as a moderate of the Tuisto Party, which won him a decent amount of cooperation from the PKU.

Surely enough, by negotiating with his ideological rivals, Heinrich von Gagern would eventually get his progressive income tax to be passed through the Bundesrat and approved by Victoria. Throughout the subsequent weeks, Gagern would oversee the ratification of numerous new stock market and banking regulations by the Germanian government, including the regulation of trading and debt securities by the Imperial Ministry of Finance. These reforms were begrudgingly supported by conservatives who conceded that more oversight of the stock market was necessary if the Great Crisis were to be avoided, and both Riebeeckia and India would mimic many of Gagern’s regulation reforms, which were revolutionary for the time period. Of course, these reforms came slowly in both Germania and abroad and were simply not enough to recover from the fallout of the Great Crisis, instead being measures designed to avoid such a catastrophe yet again. Just like the rest of Europe, the Decade of Despair was unavoidable for Germania and would wreak havoc on the entirety of the nation for the next handful of years.

In the context of Germania, the Decade of Despair predominantly reared its head in the form of riots. The goals of the riots that were commonplace throughout much of the Germanic Empire circa 1852 and 1853 varied from desperate attempts to seize resources to specific ideological aspirations fueled by the mass discontent of the Great Crisis, however, very broadly speaking, the general ideological goals of the riots, or at least the best organized and longest-lasting ones, were the expansion of the rights of the people of Germania, a nation that had no bill of rights outside of a general outline of the judicial process. While Heinrich von Gagern and much of the Tuisto Party sympathized with the goals of the riots, even if he did condemn the method itself, the PKU and the Germanian nobility, including Empress Victoria herself were infuriated that their subjects dare rise up in opposition to the Germanian state. Under the leadership of Victoria herself and her cabinet ministers, the Imperial Germanic Army would be mobilized against the Germanian Riots of 1853 starting in January 1853, with a nationwide curfew being subsequently implemented. Seeking to avoid the fate of her grandfather, Victoria ordered her military forces to only contain riots rather than actively fight against, but violence at the hands of the armed forces was seemingly inevitable, with panicky Germanian soldiers firing into a crowd of protestors, who had been throwing rocks at them, in the city of Jever on February 4th, 1852.

The Jever Massacre quickly caught national attention and infuriated rioters, with subsequent violence becoming so widespread that many anticipated a civil war. These fears were only further exaggerated when, after many days of clashes in the streets against soldiers, a mob of Jeverish revolutionaries overthrew the Principality of Jeverland’s monarchy on February 9th, 1852 and declared the Republic of Jeverland as an independent city-state, thus severing all ties with the Germanic Empire. The Germanian monarchy fervently opposed such a declaration, as did Heinrich von Gagern, who saw the secession of Germanian territories counterintuitive to his goal of establishing a new national identity for the Germanic Empire, thus prompting an immediate military response that was universally approved by the entire Imperial apparatus of state. Interestingly enough, the Jever Revolution also turned away many liberal revolutionaries across Germania, who opposed secession in favor of a complete reformation of the Germanic Empire itself and therefore interpreted the secessionists in Jeverland as a separate movement altogether. As a consequence, there were no attempts to copy the Jever Revolution elsewhere in Germania.

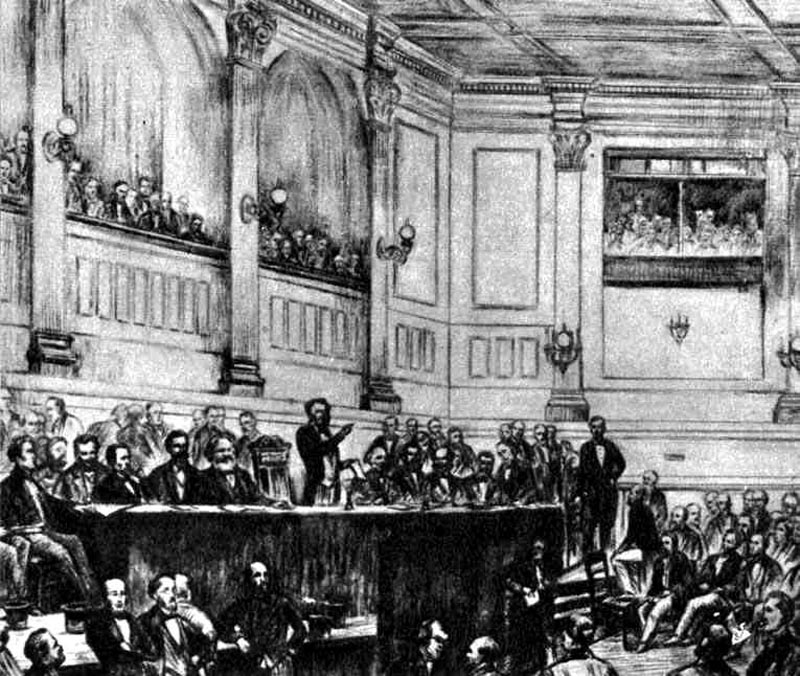

After no more than a week, the Republic of Jeverland was defeated by the Germanian armed forces when the city of Jever fell and the Principality of Jeverland was later restored on February 15th, 1852. After the defeat of the Jever Revolution, many Germanian conservatives called for similar military action against the numerous spontaneous riots across the rest of the Germanic Empire. Gagern was openly and furiously in opposition to such calls, going as far as to give an impassioned speech before the House of Commons in which he denounced military action against rioters as treason to both the Germanic Empire and its people, with such drastic measures “surely condemning the sacred institutions of our people’s mighty empire to a fate shared with the fallen British Kingdom.” As the Germanian Riots of 1853 raged on, Heinrich von Gagern would organize meetings with both Empress Victoria and the PKU leadership to negotiate a resolution to the riots that would not end in bloodshed.

In their private meetings, Gagern would eventually persuade the Empress to publicly endorse his plan for the drafting of a Germanian declaration of rights, akin to the constitutional titles that already existed within the world’s various liberal democracies, from Riebeeckia to France to Columbia. With Victoria on Gagern’s side, it was only a matter of time until the Convention of Rights was organized in Hanover, with representatives from across Germania arriving to codify a declaration of rights into the Germanian constitution as a slew of amendments. Even the United Dominion of Riebeeckia would send an ambassador to the historic convention, with famed General Otto Bismarck being personally dispatched to Hanover by Chancellor Maartin Van Buren as an advisor from a Hanoverian Realm that had already had its own declaration of rights. After numerous days of debate, “The Amendment of Rights for the Germanic Man” was ratified by the Convention of Rights and then later implemented into the Germanian constitution with approval from both the Bundesrat and Empress on March 3rd, 1853.

With its ratification by the Germanian government, the Amendment of Rights guaranteed the freedoms of speech, assembly, petition, press, and religion (this was particularly important in a nation with a very distinct divide between Protestants and Catholics amongst its constituent monarchies) to all Germanian citizens (as was the case in the time period, however, these rights did not extend to colonial territories), while also enshrining the right to an eight-hour workday, the right to every Sunday as a national holiday, and the abolition of child labor as a way to appease disgruntled workers and populists following the uproar of the Great Crisis. The Amendment of Rights would also provide governmental change by giving the Bundesrat the ability to nominate and recall executive ministers, powers that had previously been exclusively reserved to the ruling Germanian monarch. The ratification of the Amendment of Rights did not end the Germanic Empire’s economic woes, and just like the rest of Europe, Germania would have to suffer the Decade of Despair for the next handful of years. However, what it did do is peacefully advance goals of the liberal and subsequent populist movements that defined much of 19th Century politics within Germania, thus moderately liberalizing the state and likely averting a civil war.

In the aftermath of the Convention of Rights, Heinrich von Gagern and the Tuisto Party’s goals moved towards promoting their vision of a new and distinctly Germanic national identity within the Empire. The program of Kulturgebaude (“Cultural building”) would encompass Germania for the next handful of years as Gagern promoted a resurgence in ancient Germanic tribal cultural and artistic elements through a combination of national art exhibitions, architectural programs, as well as a slew of new educational curriculum that highlighted the Germanic tribes. This latter element of Kulturgebaude was arguably the most influential, as it was through the new curriculum that ancient Germanic history, culture, and art were thrusted upon the psyche of Germanian schoolchildren. Even the ancient Germanic language was resurrected, as Common Germanic became widely taught, with the vast majority of Germanian children speaking at least some Common Germanic by 1860.

All programs of Kulturgebaude served the purpose of creating a unified national identity throughout the Germanic Empire, which was viewed by the Tuisto Party as a necessity in order to shift Germanian society away from orbiting around its aristocracy and instead around its people. While outdated in the eyes of a present day that saw the horrors of nationalism at its absolute worst throughout the Titanomachy, this philosophy was actually very commonplace throughout European monarchies in the 19th Century due to many of these states being founded upon the basis that the purpose of states was to serve as a divinely-ordained domain of a monarch. While the idea that states should serve as an apparatus to advance the rights of their people had emerged at this point, it was much more prominent in republican and communist nations where the value of popular sovereignty had no divine right to clash with. In conservative monarchies, the concept of states being the spheres of specific national identities aligned much better with monarchism as the monarchy was often interpreted as a part of this identity, therefore allowing for a form of nationalism that argued that the state should have an identity beyond that of the monarchy to revolve around to serve as both a means of advancing liberalism and preserving monarchism.

The mixture of 19th Century liberalism with nationalism as a tool of working around monarchism became the basis for a new school of liberal thought deemed heutigism, which advocated for a decline in social and economic inequality, the establishment of basic universal rights, increased access to education, a capitalist market, and the basis of the state becoming a national identity rather than aristocracy. The de facto ideology of the Tusito Party, the heutigist ideology would spread to neighboring absolute monarchies, such as Prussia-Poland and Russia, as its concepts were codified by TP statesmen and philosophers in Germania. Throughout the Decade of Despair and the following years, heutigism would become the predominant populist ideology throughout eastern Europe, as it was viewed by many as a solution to both the Decade of Despair and already abhorrent conditions for the general masses of Europe’s remaining absolute monarchies. For some intellectuals, heutigism won support for the ulterior motivation of forging national identities that harkened back to pre-Roman Paganism, with ancient Roman cultural influences becoming more controversial across Europe following the communist revolutions of the 18th Century that greatly admired the Roman Republic.

As the Germanic Empire gradually recovered from the Great Crisis, Heinrich von Gagern would turn to the question of what to do with the former colonial empire of the HOK. With the collapse of the conglomerate, all of its holdings in southeastern Asia and Australasia were immediately annexed into the Germanic Empire as colonies directly administered by Hanover, however, numerous statesmen and nobles within Germania did not want to suddenly directly manage such a large colonial empire. While the annexation of previously corporate territory had been something conducted once before when the VOC collapsed and its colonies were integrated into the direct rule of Hanover, acquiring the expensive colonies of the HOK during a global depression was not an appealing option. Some statesmen proposed that what had once been Hannoveraner Malaiisch would become an independent dominion of the House of Hanover ruled by its current colonial administration, however, this seemed unsustainable. Instead, a convention of Germanian, Riebeeckian, and Indian ambassadors was organized within Singapore to negotiate the partition of the HOK’s colonies in March 1853.

As the nation that had done the most fighting during the War of Malacca, was the closest to the Malay Archipelago, and was the least affected by the Great Crisis of 1852 out of the three participants of the Congress of Singapore, the Kingdom of India was in the best position to acquire territory from the remains of the HOK. With little fuss from foreign ambassadors, India was awarded Java, numerous smaller islands to the east, and northern Sumatra by the Congress. While the northernmost part of Indian Sumatra fell under the control of the restored Sultanate of Aceh as a princely state of the Kingdom of India, the rest of India’s new territory was directly administered and integrated into the central Indian government, just as territories invaded in the War of Indian Unification had been decades prior. Much of the region had once been within the sphere of influence of the Chola Dynasty many centuries prior, and King Krishnaraja Wodeyar III made sure to emphasize this legacy throughout the assimilation of his new holdings.

As for the United Dominion of Riebeeckia, the nation had much less authority in Southeast Asia and had suffered much more from the Great Crisis of 1852, however, Chancellor Maartin Van Buren nonetheless took interest in staking out a Riebeeckian holding within the highly lucrative region. The UDR was ultimately not rewarded much at the Congress of Singapore, however, it did nonetheless acquire the entirety of the island of Timor, which was definitely not something to scoff at. With infrastructure on the island already in place from its time as a Portuguese, Brazilian, and later HOK colony, the Timor Territory was able to be turned into a highly profitable trading port for the United Dominion, which found itself with close access to the markets of Asia, Australasia, and even the Pacific as a consequence. As for the rest of Hannoveraner Malaiisch, the colony would simply be transferred over to the Germanic Empire as the colony of Germanisch Malaiisch, which remained independent of the Germanic East Indies, thus dividing the Malay Archipelago into two separate Germanian colonies.

Far away from the Malay Archipelago, the nations of the Columbian Coast would face the effects of the Great Crisis just as severely as Europe. The Decade of Despair would more or less encompass the entirety of the region, with economic recessions being felt from Acadia to New Africa during the 1850s. However, for the most part, the Great Crisis of 1852 had little long-term effects on the Columbian Coast or, for that matter, much of the New World at all. Domestically, the nations of the region faced slight political upheaval as new leaders entered office in an attempt to solve the economic crisis, but there were no large ideological shifts faced in this region, and most of the economies in the New World hit by the Great Crisis had recovered well before the Decade of Despair ended for Europe. In the end, the biggest effect the Decade of Despair had on most nations along the Columbian Coast was that it accelerated the process of regional reliance on trading networks with Africa due to the continent barely being hit by the Great Crisis.

The exceptions to this rule were the Confederation of Columbia and the Republic of Virginia. Within Columbia, which had already undergone a dramatic shift in its political landscape two decades prior following a domestic recession in the late 1820s, the poorly-handled aftermath of the Great Crisis had a profound effect on the general election of 1852 and the subsequent political landscape of Columbia going into the prelude of the First Potomac War. Following the end of Prime Minister Robert Owen’s administration in 1841, New York MP Thurlow Weed was nominated by the National Republican Party for the prime ministry and narrowly beat New York City Mayor Samuel Tilden in the 1840 election. Being more socially moderate than many of his fellow National Republicans, Weed primarily focused on implementing a protectionist economic policy (tariffs against the Comintern were particularly prominent throughout his administration) and reinforcing the centralization of the Columbian economy. The protectionism of the Weed ministry would be particularly controversial, with many businesses throughout western Columbia frequently trading with Gallia Novum, thus causing Weed to lose his re-election bid to Joshua Reed Giddings of Pennsylvania, Prime Minister Owen’s former Minister of the Treasury.

Prime Minister Joshua Reed Giddings of the Confederation of Columbia.

The ministry of Giddings was more or less unremarkable, with a very large portion of his time being dedicated to “damage control” caused by the Weed ministry. For example, the first year of the Giddings administration was predominantly spent undoing the slew of tariffs implemented by his predecessor, with the undoing of harsh protectionist policies against Gallia Novum being a top priority. As the former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Giddings also took great interest in foreign policy throughout his ministry and would pursue building up both diplomatic and economic relations with the world beyond the Columbian Coast. Most notable of these agreements was the Treaty of Dover, in which the Confederation of Columbia and the Hanoverian Realms agreed to a reduction in trading barriers, a limitation on barriers for accessing ports, and the establishment of a non-aggression pact between the two parties present at the Treaty of Dover.

While many of Giddings’ actions were ultimately beneficial to the economy of the Confederation of Columbia, this of course does not necessarily translate into a beneficial situation for the people. While corporations and merchants thrived, the Giddings administration paid very little attention to the stagnating wages of Columbian workers and, despite a handful of attempts by his ministry, the highly centralized concentration of wealth financed by the Bank of Columbia that was a priority for the Weed administration ultimately stayed in place, in part due to a National Republican majority within the House of Commons following the 1846 midterm election. Joshua Reed Giddings was a far cry from the aivd populism and egalitarianism of Robert Owen, and as such lost much of the support of the Columbian working class that had so often voted for the Liberty Party throughout the last two decades. As a consequence, Giddings would lose his re-election bid in 1848 to William Buchanan, an outspoken social conservative, protectionist, and Thurlow Weed’s former ambassador to New Granada.

Buchanan would be the man that would lead the Confederation of Columbia into the Decade of Despair.

Prime Minister William Buchanan of the Confederation of Columbia.

The son of a wealthy merchant and educated woman who had grown up in what would eventually become the easternmost reaches of the province of Howe, Buchanan would first enter politics in 1816 upon being elected to the Appalachian provincial House of Commons as a Whig, where he would push for, among other things, private deregulation, increased banking centralization, and tariffs on goods imported from Gallia Novum. Six years later, William Buchanan was elected to the national House of Commons, where he would continue to affiliate with the Whig Party up until the Panic of 1828 and his subsequent switch over to the Anti-Masonic Party. Buchanan would rise through the ranks of the Anti-Masonists throughout the Ritner administration and would eventually wind up becoming the Leader of the Opposition following the 1836 general election.

Upon being nominated by the National Republican Party for the prime ministry in 1848, Buchanan was, for better or worse, one of the most notorious members of the party in all of Columbia. A far cry from the moderation of Thurlow Weed, Buchanan would promote one of the most socially conservative agendas in Columbian history by severely limiting immigration (immigration from Great Britain and France, as well as the immigration of any Catholics, was completely banned by his administration), providing tax benefits to Protestant churches, and vetoing any national programs aimed at increasing social equality, particularly amongst women. Buchanan was also avidly in favor of tariffs and would, with a National Republican parliament on his side, reintroduce many of the protectionist policies implemented on the Comintern by Weed and repealed by Giddings, thus creating a sort of tug of war regarding tariffs between the National Republicans and Libertists.

An ambitious politician who sought to enforce his reactionary agenda upon the Confederation of Columbia, Buchanan believed that he was to become one of the greatest prime ministers in Columbian history, aided by a National Republican parliament, even after a handful of seats were lost to the Liberty Party. Of course, this was not to be. The Great Crisis of 1852 had to occur at the worst possible time for William Buchanan, with the November 10th election being a little over a month away from the total collapse of the global economy that Columbia was very much integrated into. By this point, the Liberty Party had already chosen its candidate, egalitarian MP Orestes Brownson of New York, who was quick to criticize Buchanan for his poor handling of the Columbian economy and called on a dramatic economic and political shift to combat the fallout of the Great Crisis. With little opportunity spared to implement recovery methods as the depression gradually got worse by the day, William Buchanan would handedly lose the 1852 election, thus handing the prime ministry over to the eccentric Orestes Brownson on January 20th, 1853.

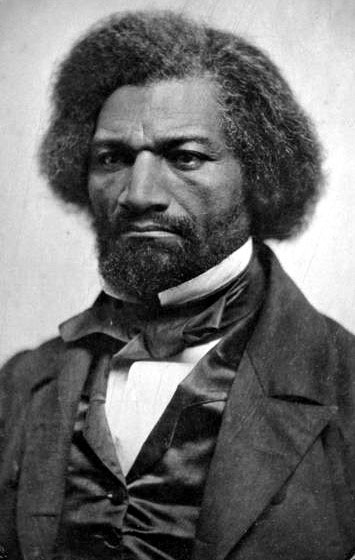

Prime Minister Orestes Brownson of the Confederation of Columbia.

Born to Loyalist farmers originally from Vermont that had moved to New York during the Wars of Dissolution, Brownson had very different origins than that of his predecessor, William Buchanan. Receiving little formal education, Brownson briefly got himself involved with Universalism early into his adulthood, going as far as to become the editor of a Universalist journal. However, this period of his life was short-lived, as Brownson eventually began to express disillusionment with his own religious beliefs and would leave the Universalist church prior to leaving for New York City. It was in New York City that Brownson would get involved in politics by joining the Working Men’s Association, a socialist political party formed by a collection of trade unionists in New York who adhered to the ideals of Charles Fourier. While only focusing on electoral activities within the New York province, the Working Men’s Association saw impressive success in provincial and urban elections, with Orestes Brownson actually being elected to the New York City Council in 1829.

From here, Brownson would become a prominent leader of the Working Men’s Association, which was collectively becoming a prominent force for labor rights in and of itself. In 1834, the party would vote to join the Libertists due to negotiations with New York Liberty Party members, who also happened to support much of the Working Men’s Association’s platform, which was reflected in Prime Minister Robert Owen’s policies, and Brownson would subsequently run for a seat in the House of Commons on behalf of the Liberty Party in the 1834 general election. In Parliament, Brownson would be a staunch ally of Robert Owen and consistently advocated for increased labor rights throughout both the Owen ministry and subsequent administrations. MP Orestes Brownson carried the torch of the age of Robert Owen’s radicalism through the reigns of two National Republicans, even as the Liberty Party consolidated around Giddings’ moderation. As the Libertist base grew tired of the increasingly gilded policies of moderate party leadership, Orestes Brownson would thus ride in on a wave of working class support to the 1852 Liberty Party prime ministerial nomination, which he in turn rode to victory alongside general outrage at the National Republican handling of the Great Crisis and defeated incumbent Prime Minister William Buchanan.

Upon entering the prime ministry in January 1853, Orestes Brownson was faced with recovering the Confederation of Columbia from the greatest global economic crisis since the 17th Century. Prime Minister Brownson would quickly call on the immediate dissolution of many of the monopolistic banks and corporations that had collectively lost billions of sceats and sent Columbia careening into the Decade of Despair, with the Liberty Party-dominated Parliament approving of this agenda by passing the Acts Against Monopolism, as the prime minister branded them, throughout the late winter and early spring of 1853, which dissolved the largest corporations in the Confederation into much smaller corporate successors, with Brownson hoping that such actions would prevent large industrial entities from infringing on labor rights and accumulating enough wealth to have a dangerous effect on the Columbian economy. Furthermore, many of the Acts Against Monopolism effectively nationalized much of the wealth and resources of large corporations as a means to fund the greater ambitions of the Brownson ministry.

These resources were in turn used for a number of recovery programs put forth by Brownson to pull the Confederation of Columbia out of the horrors of the Decade of Despair. The first of these programs was the Yeoman’s Act of 1853, which would redistribute acres of land seized from wealthy individuals to poorer families, particularly those who had been economically hit hard by the Great Crisis. Serving as a means to both aid those struggling from the fallout of the Great Crisis and to chip away at the social power of the oligarchic ruling class of Columbia, the Yeoman’s Act established a program in which families and individuals would apply for plots of land of up to 160 acres to occupy as personal property until one’s death. The Yeoman’s Act would narrowly pass through Parliament and was ratified into law on March 2nd, 1853 by Prime Minister Brownson in the face of ardent National Republican opposition. Despite being a partisan issue of the day, the Yeoman’s Act proved to be highly successful and popular amongst the general public, for whom the program became a pivotal means of providing relief from the greatest economic catastrophe in centuries. With Libertist support surging as a consequence, “Every Man a Yeoman” in obvious reference to the Act became a rallying cry for Orestes Brownson during his 1856 re-election bid.

After the passage of the Yeoman’s Act, the Brownson ministry continued to push for economic relief, including wage boosts, continued anti-monopolization practices, and the nationalization of numerous banks, all of which became the consistent themes of legislation throughout the Brownson administration, as such actions were viewed as necessary for economic recovery and the overall ideological goals of the Liberty Party. Furthermore, Brownson, who admired the efforts of Heinrich von Gagern to reign in reckless market leadership via government stock exchange regulation, would implement a similar policy within the Confederation of Columbia via the National Regulation Act in May 1853. However, as the effects of the Great Crisis began to calm down, Orestes Brownson would begin to heavily promote communalism and education reform as a substantial priority of his administration. After all, before the global economy had collapsed, a pivotal aspect of Brownson’s campaign had been communalism for the sake of promoting egalitarian prosperity. With things finally stabilizing and the public on his side (especially after the expansion of the Liberty Party to contain a majority of seats in both houses of Parliament following the 1854 midterm election), Orestes Brownson decided to advance such policies when the wind was to his back.

Education reforms initially began as slightly increasing funding for Public education programs, which was no doubt appreciated by Brownson’s supporters, however, the goals of the prime minister were far more ambitious than funding increases. In a policy borrowed from his days within the Working Men’s Association, Orestes Brownson envisioned a communal education system in which local community councils would democratically manage educational affairs with input from students, teachers, and the wider community alike. Furthermore, Brownson believed that schools could serve as the backbone for generating public discourse and concluded that his community-managed assemblies would promote this. The idea that schools could generally become the backbone for overall communal living taking effect was greatly admired by Brownson and fueled his call for schools to, among other things, distribute meals to students, provide community service, and invest in public libraries.

These grandiose ambitions of Brownson to turn the education system into the sword of communalism would be hotly debated even within his own party, as many moderate Libertists were extremely hesitant to enact explicitly communalist policies. Radical populism had gripped the Liberty Party for decades at this point, but hardline communalism was something that the classical liberal old guard of the party was extremely hesitant about, even as Robert Owen-esque populists like Brownson made up a majority of the Libertist leadership and base at this point. It would take Robert Owen’s eldest son, one of Pennsylvania’s most prominent MPs, and Orestes Brownson’s minister of education, Robert Dale Owen, to pass Brownson’s educational plan into effect. An ardent supporter of communalism himself, Minister of Education Owen was firmly behind the proposals of the prime minister and would passionately advocate for them in Parliament, subtly build up public support, and gradually force the Libertist old guard to concede to the approval of Brownson’s education plans. One by one, these communalist bills slipped through Parliament and were ratified by the prime minister only for their implementation to be presided over by Robert Dale Owen. For overseeing these programs from their conception to their enactment, the Brownson ministry’s numerous communalist educational bills were nicknamed the Dale Acts.

Minister of Education Robert Dale Owen of the Confederation of Columbia.

Going into 1856, Orestes Brownson was very popular amongst the Columbian people and appeared to be able to ride a wave of populist support to a decisive re-election. As the masses rallied around Brownson’s re-election bid, the National Republican Party would nominate former Delaware Governor William Tharp, who ran a campaign advocating for a return to the pre-Brownson status quo, a reinforcement of tariffs upon the Comintern, and a foreign policy that would economically and politically isolate Columbia from European affairs as to severe ties from the failing global economy. Tharp campaigned well, but after the very successful first term of Orestes Brownson, which had overseen gradual economic recovery and extensive welfare programs, very few wanted a return to the National Republic status quo that had most recently led the Confederation of Columbia into the Decade of Despair. Therefore, Orestes Brownson was handedly re-elected to the prime ministership in 1856, winning a stable majority in every province except Delaware, where Tharp narrowly emerged victorious on home turf.

The second term of Prime Minister Orestes Brownson would be much less eventful than the last, as Columbia was on a steady path to economic recovery at this point and the Libertists believed that simply a continuation of the relief programs of the last four years would safely lead Columbia out of the Decade of Despair. The Yeoman’s Act was extended and Minister of Education Robert Dale Owen would continue to preside over the nationwide implementation of the Dale Acts while Parliament provided his ministry with increased funding. There were, however, a few pivotal new policies introduced in the otherwise quiet second term of the Brownson ministry. In September 1857, the Ministry of Agriculture would be created to overlook national agricultural regulation, production, and policies. As much of the land redistributed in the Yeoman’s Act was farmland, much of the early responsibilities of the Ministry of Agricultural revolved around the redistribution system of said Act and making sure that farmland up for redistribution was arable to begin with.

The far more important action undertaken by Orestes Brownson during his second term was the creation of numerous new provinces, something that had not been done since the secession of Appalachia from Pennsylvania in 1809. By the 1850s, it was clear that political power within Columbia had effectively consolidated around the provinces of New York and Pennsylvania, which were much larger and more populated, than New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Howe. Just by looking at the list of prime ministers, it was clear that a solid majority were from New York alone. While many didn’t see the point of further partitioning Pennsylvania after the establishment of Appalachia out of its westernmost reaches, New York remained very large and very populated and calls for its dissolution into smaller provinces had emerged every now and then over the last few decades.

The partition of the province of New York was something that Prime Minister Orestes Brownson had never really advocated for (he was, after all, from New York), however, in June 1858, National Republican MP Fernando Wood, a resident of Manhattan and long time proponent advocate for the increased autonomy of New York City as a means to increase its economic influence, would propose a bill to the House of Commons that would establish the Province of New Liverpool out of Manhattan, Long Island, and Staten Island. While Wood’s proposal likely wouldn’t have gotten far in local New York politics, by introducing it to the national Parliament, which held the authority to establish new provinces with the approval of the prime minister, he managed to interest numerous MPs of both the National Republican and Liberty parties who sought to weaken New York’s power within the Confederation. As the New Liverpool proposal began to be hotly debated within the House of Commons, local secessionist movements that endorsed said proposal also began to emerge throughout New York City and Long Island, thus generating local support.

After lengthy debate, the Bill for the Declaration of the Province of New Liverpool narrowly passed through both houses of Parliament on July 6th, 1858 despite the protests of Albany and would subsequently be ratified by Prime Minister Orestes Brownson, who had more or less remained quiet on the subject but conceded that the establishment of a new province from New York was justified by local support. Therefore, once the national Columbian government recognized the Province of New Liverpool and a provincial constitution was ratified on July 21st, 1858, the seventh province of the Confederation of Columbia was officially created. The creation of a new province by Fernando Wood from New York opened up the door for groups across the province’s frontier, who were disgruntled with their treatment by Albany, to call for secessionist movements of their own. In the end, a total of three more provinces would be created from New York. The first of these would be the Province of Haudenosaunee, which was established on January 3rd, 1859, and was more or less the Iroquois Confederacy, as the white Columbians referred to it, being granted provincehood. A few months later, the remaining western reaches of New York would secede and form the Province of Erie on August 12th, 1859.

While the Confederation of Columbia would quickly recover from the Great Crisis and adopted a new domestic political situation in the process, its neighbor to the south was a different story. Like Columbia, the Republic of Virginia was to hold a general election in 1852, with President-General Edward Houston of the nationalist Washingtonian Party running for his fifth term, for the first time in Virginian history since the days of Henry Lee III, unopposed. In the fifteen years since he first assumed power in January 1837, President-General Edward Houston had militarized Virginia into the state with the third largest standing armies in the New World behind New Granada and Mexico (this was, however, admittedly helped by the rapid reduction in the sizes of the Peruvian and Brazilian armed forces by the Treaty of Belem) an industrialized economic powerhouse, and a heavily centralized regime in which the Washingtonian Party had no chance of losing power. With the Washingtonians and military effectively jointly managing the apparatus of state by nominating and financing the political campaigns of sympathetic officials, the Republic of Virginia had effectively succumbed to oligarchic republicanism while the Centrist and Liberal-Democratic parties gave up on national politics and focused their resources on local affairs.

As the Republic of Virginia fell under the sway of Houston’s regime, so to did it fall under the sway of the Washingtonian Party’s nationalist cult of personality that revolved around the Forefathers of the Columbian Uprising, particularly General George Washington, who Edward Houston often referred to as the “Great Martyr.” To the Washingtonian Party, these men had fought for the cause of a great American Republic in the form of the United States of America and it was the duty of the Republic of Virginia to carry on this cause that the Forefathers had died for. The “Lost Cause” mentality, as this philosophy began to be known as, was the driving force for much of Virginia’s political ideology throughout much of the Houston administration, and this was reflected in education, cultural rhetoric, and even architecture. Perhaps the most notable physical example of the Lost Cause was the Pillar of the Great Martyr, a titanic monument built in honor of George Washington nearby Mount Vernon, his former residence, that began construction in 1839 and, upon its completion in 1867, was briefly the tallest structure on Earth.

The Pillar of the Great Martyr.

The effects of the Lost Cause mentality extended beyond monuments to fallen revolutionaries and the glorification of the United States of America in the textbooks of Virginian school children. The ideology was very much a driving force in both foreign political affairs for the Republic of Virginia, with the interpretation of the Confederation of Columbia as a successor state to the Kingdom of Great Britain reigniting hostile relations between the two states after heads of government from both Columbia and Virginia preceding Houston had spent decades attempting to secure decent relations. This never translated into expansionism to unite the Columbian Coast under a single banner, just as it had been during the days of the United States, due to Edward Houston prioritizing the buildup of domestic power in advance and envisioning Virginia’s role as that of a guiding force for Columbian republics anyway, however, it did cause Virginia to place a heavy focus on getting what had once been the Union of Atlantic States to be economically reliant on the Republic of Virginia as Houston’s foreign ambassadors consistently snuffed out foreign competition via trading pacts and tariff reductions.

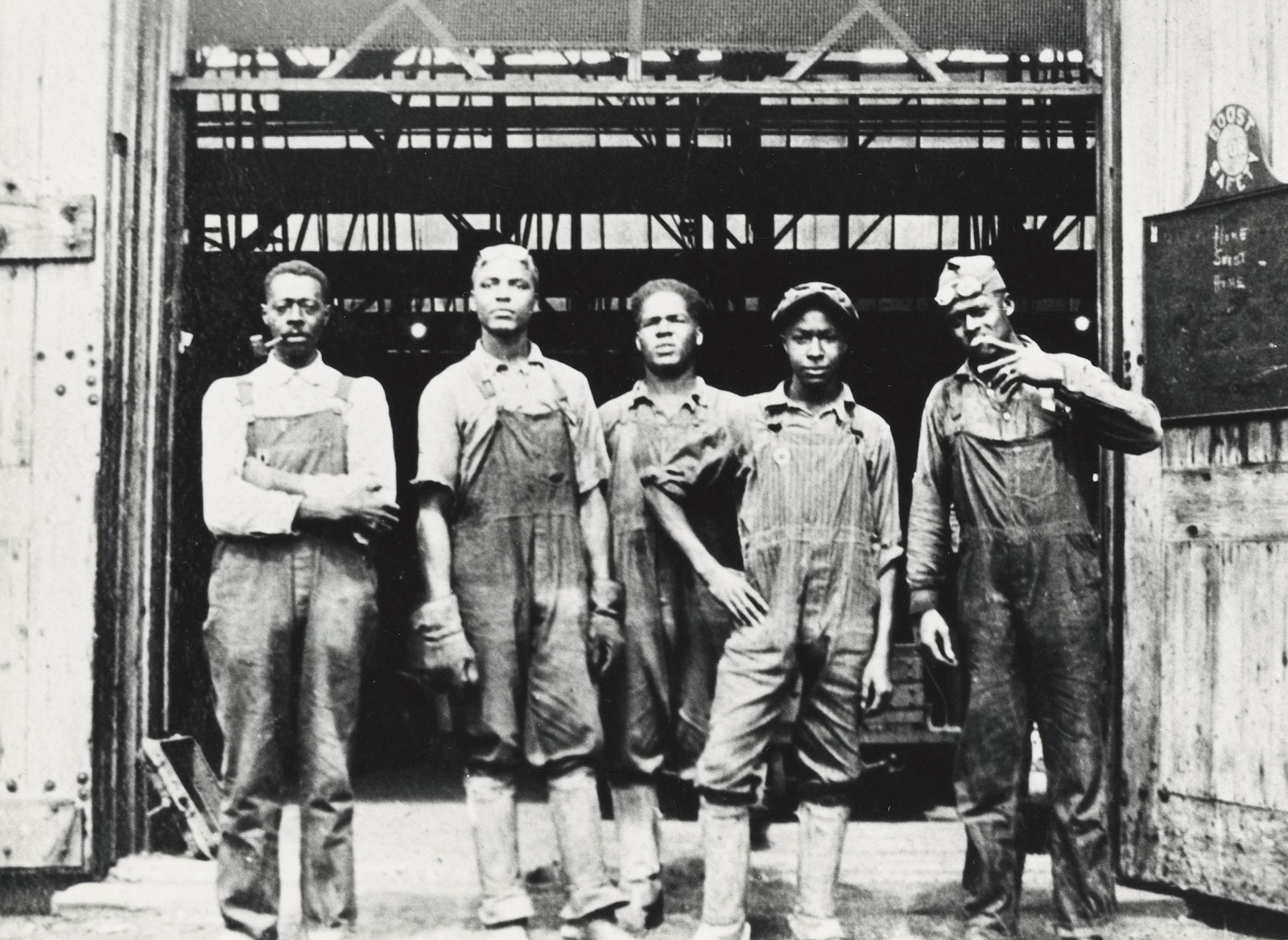

During the Houston administration, the only expansion the Republic of Virginia would see was in its small colonial empire in West Africa, which had proven to be immensely lucrative since its establishment in the late 1830s. Expansion throughout much of the 1840s was limited to slight border reinforcement, however, around 1848 the Bate Empire, which was situated between the Virginian West Africa and Ashanti Empire and was to the north of Cote du Poivre, began to limit trading relations with Virginia as Imperial Ashanti Company made moves to economically influence the Bate Empire into the orbit around the ever-growing and ever-industrializing Ashanti Empire. The coalescing of the Bate Empire into the Ashanti sphere of influence was critical, as the state’s capital of Kankan was a pivotal trading center in the region, and the growing exclusion of Virginian West Africa from trade with Kankan would effectively cut off Virginia from any fostering of profitable trading relations with the region. In the eyes of President-General Edward Houston, this required conquest to ensure direct rule over Kankan and thus Virginian control over the vital trading center.

The Bate War would begin on October 3rd, 1848 and was, for all intents and purposes, a quick and mostly painless war for Virginia. The Bate Empire may have been better equipped than it was less than a decade ago thanks to trading with the industrialized Ashanti Empire, but it still stood no chance against the vastly larger and more modernized Army of Virginia, and the only chance of survival for the Bate Empire was intervention on their behalf from Ashanti, which never arrived, as the empire was still consumed in the Kwakan Wars and didn’t want to waste resources in a war of attrition against Virginia. The leading Virginian military officer in the Bate War was General Richard Randolph Lee, the youngest of former President-General Henry Lee III’s three sons, who had used both his heritage and military capabilities to rise to the top of the ranks of the Army of Virginia, being second only to the president-generalship by 1848. Lee made quick work of the Bate Empire by leading a rapid and aggressive offensive that mounted higher casualties than he would have liked but nonetheless ended up winning the Bate War for Virginia in less than a month, with the Bate leadership unconditionally capitulating following Richard R Lee’s decisive victory at the Battle of Kankan, circa October 27th, 1848.

The subsequent result of the Bate War was the establishment of the Gates Colony (named in honor of Continental Army General Horatio Gates) out of, in the words of the Gates Colony Charter, “the territory previously encompassed by the Bate Empire and all other surrounding territories currently occupied by the Army of Virginia.” The establishment of the Gates Colony in the middle of a crucial trading region would cause the neighboring New Occitanians and Ashanti to question the sudden Virginian takeover and push forward their own claims in the area, thus prompting local Virginian colonial authorities to organize a conference at Kankan to partition what remained of the land surrounding the Gold Coast between Virginia, Ashanti, and New Occitania. Signed on December 1st, 1848, the Treaty of Kankan would recognize a handful of westward Ashanti claims, extended the New Occitanian colonies of Cote du Poivre and Cape Mesurado northwards, and, arguably most significantly, recognized the Gates Colony and solidified its borders. As an added compensation for what was basically the handover of a crucial trading center to the Republic of Virginia, all three signatories also agreed to lower tariffs on each other and Virginia agreed to not restrict access to Kankan, except during any potential wartime between the signatories.

The Virginian state of affairs going into the 1852 president-generalship election and the Decade of Despair was more or less the one that had been forged at the Treaty of Kankan. No expansion had occurred since Richard Randolph Lee’s conquest of the Bate Empire while foreign and domestic affairs more or less remained consistent throughout Edward Houston’s fourth term. The Virginian general election was held on September 30th, 1852, days before the collapse of the Hanover East India Company and over a month before any of the effects of the Great Crisis would really hit Virginia. Not that the Great Crisis would have affected Houston’s chances anyway, given that he had built up what bordered on a cult of personality at this point and ran unopposed, thus making the 1852 president-generalship election effectively meaningless. Once the Great Crisis did impact the Republic of Virginia, things would begin to change. In a matter of days, the prosperous economy that Edward Houston had spent over a decade constructing came crashing down as the president-general frantically churned out bailouts and dissolved banks that were only losing money. And of course, always an admirer of militarization, President-General Houston would encourage joining the Virginian armed forces, which would provide sustainable food and income to its soldiers.

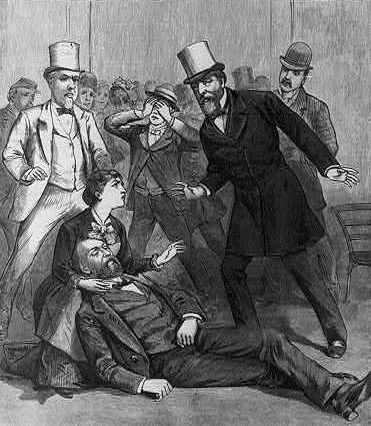

For the most part, Edward Houston’s response to the Great Crisis was supported fairly well by the people of Virginia. What remained of the Liberal Party made a bit of a resurgence in support, but the power of the Washingtonian Party was too strong to collapse under the pressure of even an economic depression at this point. But at the end of the day, Edward Houston would not oversee the recovery of the Republic of Virginia from the Decade of Despair and would only witness the entry of Virginia into the largest economic crisis of the 19th Century. On January 19th, 1853, as the president-general was giving a speech to a vast crowd of supporters in front of the Capitol building, the residence of the House of Burgesses, a lone man by the name of Francis White Johnson discreetly pushed to the front of the crowd, where he stood just mere feet away from Houston’s podium. Having recently lost his lumber mill to the Great Crisis and given no compensation from the national government except pressure to join the military, the disgruntled Johnson rapidly pulled out a pistol and, in a matter of seconds, fired towards the capital. As the startled crowd screamed at the sound of a single gunshot and police officers tackled Francis White Johnson to the ground, the assassin looked up and realized that he had accomplished his task.

President-General Edward Houston had been shot and killed.

President-General Edward Houston just after being assassinated.

With Edward Houston dead, sixteen years of the Republic of Virginia having one ruler came to a brutal end. In the case of the president-generalship being vacant, according to the constitution of Virginia, it was the duty of the House of Burgesses to elect the next president-general, but this would of course take time to organize and conduct, and in the meantime the line of succession for the interim president-generalship would pass down the military chain of command, which meant that General Richard Randolph Lee suddenly found himself leading the Republic of Virginia following the assassination of Edward Houston. As the leading military officer, who had recently returned from a decisive victory, of a highly militaristic state, Lee already found himself with strong popular and political support behind his administration, which was especially needed during the time of a great national crisis.

In order to combat the Great Crisis, President-General Ricard R Lee would quickly set up numerous military infrastructure projects focused on the construction of mechanized infantry (based off of the designs of the Kingdom of New Granada utilized during the Amazon War), naval, and aerial forces as a means to employ those that had fallen victim to the Decade of Despair. All the while, Lee navigated his way through a chaotic political situation by reinforcing his already strong support within the armed forces and amassing support within the Washingtonian Party. This was done in order to get the House of Burgesses to elect the power-hungry Richard R Lee to the president-generalship, as Lee believed that his centralized military authority was not only necessary to pull Virginia out of the Decade of Despair, but necessary to achieve his Pan-Columbian vision of rebuilding the extent of the United States of America. Surely enough, Lee’s attempt to remain the president-general was successful, and the House of Burgesses almost unanimously elected the bold general on February 19th, 1853.

With his back to the wind and the Washingtonian oligarchy behind his rule, President-General Richard Randolph Lee would start to tighten his group on the Republic of Virginia by centralizing his authority. Rival military and political authorities were ousted from power in favor of ideological allies while the House of Burgesses was pressured to pass legislation that turned Virginia into an increasingly autocratic state. In May 1853, the Sedition Act, which banned the publication of anything at odds with the leadership of Lee, the Virginian armed forces, or the Washingtonian Party, was ratified and in June 1853 habeas corpus was suspended via the Security Act. With the aforementioned legislation giving the president-general the power to effectively purge political dissidents without any legal consequences, Richard R Lee would culminate his republican seizure of power by pushing the Executive Act through the House of Burgesses in November 1853, which granted the president-generalship to pass bills without approval from the legislative branch and eliminated the legislative branch’s ability to overturn the veto of the executive branch with a three-fourths majority vote. With the passage of the Executive Act, Lee had turned himself into a de facto autocrat and was all the bit closer to achieving his Pan-Columbian ambitions.

Over the next year, Robert Randolph Lee would exert his newfound power upon the Republic of Virginia to ensure both the total loyalty of the political ruling class and the armed forces and the promotion of his Pan-Columbian ideology, the latter of which was spread through Washingtonian Party manifestos distributed to households and schools alike to enforce the mindset that it was the “divine destiny” of Virginia to unite the Columbian people under a single banner as a powerful continental empire that would eliminate all remaining traces of the long-forgotten British Empire in favor of a Virginian-esque culture and society. This was partnered with continued militarization programs (empire-building is never a peaceful endeavor) that were unprecedented even by the standards of Edward Houston’s aggressively militant administration. The length of time all Virginian men were required to serve in the military was extended from three years to six, oligarchic corporate boards were assembled with the purpose of directing the development of military infrastructure, and the assets seized from failing corporations following the Great Crisis were utilized to finance the buildup of the Aeronavy of Virginia.

The 1854 Virginian general election would be little more than an imitation of democracy, as the Liberal Party had been purged from the apparatus of state altogether while all Washingtonian Party candidates had been selected by the party’s oligarchy upon which President-General Lee sat atop. Nonetheless, with many remaining opponents to Lee within the House of Burgesses either being ousted via primaries or refusing to run for re-election altogether, the strength of the tyrant of Richmond was further solidified, and it was after the general election of September 30th, 1854 that Richard Randolph Lee made his final move to reign supreme over Virginia and finally begin his campaign of imperialistic divine destiny. On October 14th, 1854, President-General Richard Randolph Lee would rise to the top of a podium (one that notably had much more security surrounding it so as to not repeat the mistake of 1853) in front of a crowd in Williamsburg. It was here, in the former capital of colonial Virginia, that Lee would speak the Williamsburg Address to the Republic of Virginia in which he declared that the time had finally come for the Virginian nation to embrace its divine destiny.

“Three score and eighteen years ago our Yankee Forefathers sought to bring forth on this continent, a new Empire of the West, conceived in liberty from foreign tyranny, and dedicated to the union of the Columbian states. However, the Great Martyr George Washington was tragically slain in the crusade for this new empire and the Perfidious Albion would encase the North American continent in its chains of oppression yet again. But my fellow Virginians, we mustn’t forget our victory in the righteous crusade for independence of 1797, a crusade fought in continuation of the legacy of the Great Martyr against what remained of Perfidious Albion upon this very continent.

Now we are engaged in a period of great turmoil as our Continental brothers find themselves divided under petty differences, and while our mighty nation remains true to the values of our Yankee Forefathers, our neighbors continue to squabble amongst one another, and no Continental unity can long endure. We therefore are called to a great battle-field of the next war for the fate of Columbia. We have been called by our Forefathers and the Lord himself to pursue Virginia’s Divine Destiny, a noble duty that shall end the squabbles that plague this continent once and for all. By taking up the duty of our Divine Destiny, we shall carry on the legacy of our Yankee Forefathers, many of whom gave their lives eons ago so that a single Columbian nation might live. It is altogether necessary that we should carry on this legacy in the oncoming crusade for the fate of the North American continent.

It therefore is for us the living, we who welcome the journey that must be undertaken in the name of our Divine Destiny, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought who fought for the long-envisioned Empire of the West have thus far so nobly advanced. It is for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that our fallen Forefathers shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have give birth to a new and invincible empire—and that the dream of those who have come before us, from the Great Martyr George Washington to President-General Edward Houston, shall not perish from the earth.

If we are to dedicate ourselves to the great task of accomplishing our Divine Destiny, then we must recognize that we must dedicate ourselves to forging the nation that shall best lead us to victory in our grand crusade. History has shown time and time again that decentralized republics, no matter how noble their intentions, cannot succeed in the pursuit of great empire-building. My fellow Virginians, our Divine Destiny calls on us to build an empire, and every empire requires an emperor to sit atop its throne. There are undeniable gifts of imperial means of governance that we mustn’t reject, and the time has therefore come for a Yankee Emperor to lead us to a glorious victory. As my family has been dedicated to fighting for our Divine Destiny since the age of the Great Martyr, my fellow Virginians, I humbly request that, with consent from the House of Burgesses, I become the first Yankee Emperor. For the Divine Destiny!”

-President-General Richard Randolph Lee of the Republic of Virginia’s Williamsburg Address

As the crowd of fervent nationalists assembled at Williamsburg erupted into applause at the call by the president-general to declare himself the emperor of a continent-spanning empire, the days of the Republic of Virginia became numbered. The following days would be spent forging propaganda endorsing the declaration of a Continental Empire, as Richard R Lee already had the political authority to declare himself emperor and simply wanted to ensure that popular support was decisively on his side before doing so. On November 1st, 1854, the fateful day finally arrived. The president-general called upon an assembly of the House of Burgesses to vote on implementing a new constitution for Virginia that would replace the half-century old Republic with the Holy Continental Empire, a highly aristocratic federation of monarchies tied together by the centralized autocracy of its emperor. With the House of Burgesses being little more than a cabal of Richard R Lee’s loyalist advisors at this point, the constitution of the Holy Continental Empire was ratified unanimously, thus forging a state that would define the next two decades of North American history.

Flag of the Holy Continental Empire.

Before the Wars of Reunification began, the Holy Continental Empire (HCE) was actually politically very similar to the Republic of Virginia. The passage of legislation that had turned Richard Randolph Lee into a de facto dictator during his president-generalship meant that the only change necessary to establish him as an autocratic monarch was the transformation of his position into a hereditary one held for life. There were, however, a handful of other pivotal changes within the constitution of the HCE that made its government distinct from its predecessor. For starters, as the name implied, the Holy Continental Empire was an explicitly Christian state, thus repealing the guarantee of freedom of religion from the days of the Republic of Virginia in favor of a theocratic institution that Richard R Lee viewed as pivotal to the Pan-Columbian national identity. The HCE was also federally divided into constituent monarchies, defined as “electorates,” which could generally administer domestic affairs however they pleased, as long as said administration did not contradict Imperial laws.

There were some exceptions to this rule, as some electorates held varying degrees of autonomy from the central monarchy. Some electorates, for example, were ruled by the same monarch as the entirety of the Holy Continental Empire, thus meaning that they were de facto directly ruled by the central government. Alternatively, the Sahelian Protectorates of Virginian West Africa, which were integrated into the Holy Continental Empire shortly after its formation as electorates, only ceded foreign, militaristic, and economic affairs to the Imperial regime. The Continental legislative assembly was also substantially altered from its predecessor, the House of Burgesses. The Imperial Continental Congress was divided into a lower house, the House of Delegates, which was more or less a carbon copy of its unicameral predecessor and was, in theory at least, designed around popular representation, and an upper house, the House of Lords, which consisted of two representatives appointed by executive of each electorate.

Of course, at the center of the entirety of the Holy Continental Empire was its emperor, none other than Richard I of the House of Lee himself. As the ultimate executive of the HCE who also served as the reigning absolute monarch of three electorates, the Kingdom of Virginia, the Kingdom of Lee, and the Principality of Gates (the colony of Washington City was integrated directly into the Virginian electorate), Emperor Richard held supreme authority over the core territories of his empire and would rule over them with an iron fist. In order to turn his already very aristocratic and powerful family into literal nobility, Richard I would cede his relatives noble titles and would hand a select few positions of power as his representatives to Lee and Gates that would preside over day-to-day affairs in the name of His Majesty. After centuries of holding power in Virginia, the family now ruled over the state as their effective personal domain, with Richard Randolph Lee sitting upon his self-constructed throne of absolute power.

The age of Emperor Richard had begun.

Emperor Richard of the Holy Continental Empire.

Shortly after the declaration of the Holy Continental Empire, Emperor Richard would mobilize forces against the Appalachian Mountain Republic, as the first target of the Wars of Reconstruction in the name of divine destiny. On February 2nd, 1855 an ultimatum was sent from Richmond to Nashville, which demanded that Appalachia recognize Richard’s brother, Sydney Washington Lee, as their monarch. There was of course, no way that the Appalachian government would hand over its power to the HCE’s emerging dynasty, and Emperor Richard knew this, as his ultimatum to Appalachian President Lazarus Whitehead Powell was little more than a means for the Holy Continental Empire to secure a casus belli to declare war on its western neighbor. After seventy-two hours, the ultimatum went without any response and, in a speech to the Imperial Continental Congress, Emperor Richard would announce his intent to declare war upon the Appalachian Mountain Republic on February 5th, 1855.

The Appalachian War, or, as the HCE advertised it, the First War of Reconstruction, was a quick endeavor. The Appalachian mountain range did prove to serve as an effective obstacle for Richard’s forces, which he had recently named the Imperial Continental Army (ICA), to push through, but the HCE ultimately had much greater manpower than the Appalachian Mountain Republic and gradually made its way through the rough terrain and into northern Appalachia, with Lexington being secured by the ICA on April 11th, 1855, subsequently becoming a launching point for further Yankee incursions. More important to achieving victory for the HCE than its larger manpower, however, was its technological advantage. The Ohio River was filled with heavily armored Imperial Continental Navy (ICN) ships, which obliterated the lackluster naval forces of Appalachia with quick ease. On top of this, it would be in the Appalachian War that the ICN first utilized ironclad warships, an infamous staple of the First Potomac War, during a conflict. Having begun being designed following the Amazon War, in which similar iron-hulled warships were constructed by both New Granada and Brazil (although both sides rarely used them, as such technology was still in its infancy), by 1855, the ICN had plenty of ironclad ships and used only a handful to dominate the Ohio River and sink the Appalachian navy into the abyss.

On top of the usage of ironclad warships to decisively occupy the Ohio River and thus seize control of Appalachian settlements along the waterway, the Holy Continental Empire put the Imperial Continental Aeronavy (ICAN), which Richard R Lee had been particularly keen on building up throughout his reign over Virginia and later the HCE, to good use. While the Appalachian Mountain Republic barely possessed any aircraft and the ones it did have were managed by its army rather than a separate branch of the Appalachian armed forces, the ICAN was amongst the most sophisticated aeronavies in the world, having been built up over many years to ensure that the Holy Continental Empire would rule the clouds. Steam-powered airships had been commonplace within industrialized military forces since the days of the War of Indian Unification circa the 1830s, and the HCE armed forces had been sure to continue to develop this technology, alongside very early electric-powered vehicles, as airships became larger, faster, and able to carrier larger equipment, including aerial bombardments and organ guns. With some of the most effective airship models in the world, a diverse array of deadly aeronavy forces would become as common of an occurrence as clouds in the sky of the war-ravaged Appalachian Mountain Republic, which was constantly bombed by Yankee forces.

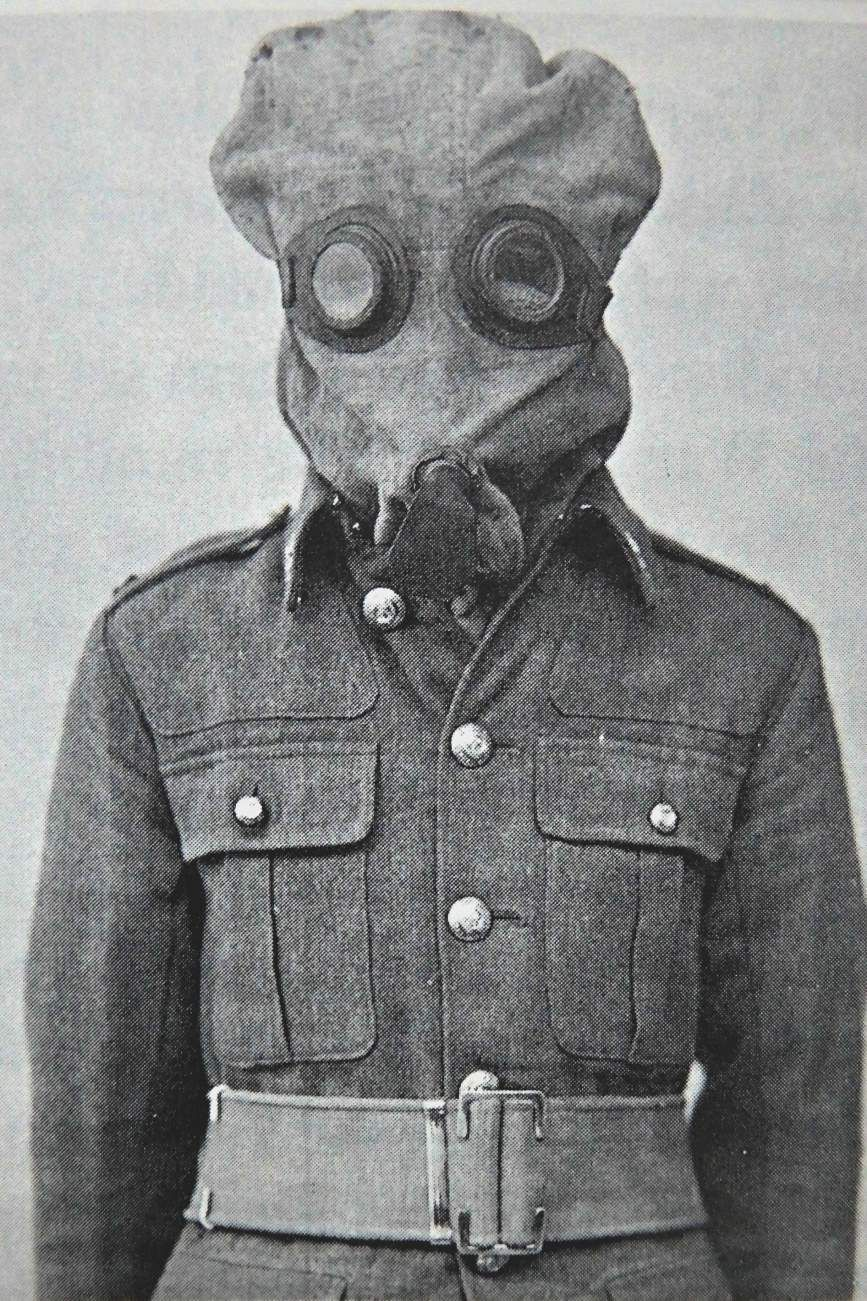

The HCAS Hancock, the first fully controllable aerial warship, which was used for reconnaissance missions and bombing runs, circa March 1855.

To the Holy Continental Empire, the Appalachian War was little more than a propaganda stunt to test out military technology and bolster public support for the Wars of Reconstruction. To the Appalachian Mountain Republic, the Appalachian War was total destruction the likes of which North America had never before witnessed. The aggressively relentless bombardment of Appalachia, which often targeted populated centers of strategic importance, was often condemned by the neighboring international community as nothing short of barbaric carnage. Concordia and Gallia Novum both levied limited sanctions on the HCE, which was already beginning to be perceived as an increasingly rogue state in the region, while Prime Minister Orestes Brownson, despite not wanting to harm foreign relations during a period of great domestic economic instability, issued a letter personally to Emperor Richard urging him to call off the aerial bombardment of civilian targets. “If what the Appalachian Nation claims is true,” wrote Brownson, “this tactic has brought upon a fierce storm of fire and bloodshed. Only in Hell does it rain fire; we need not bring this torment to Earth as well.”

Of course, these condemnations from the international community were ignored by Emperor Richard I, who embraced the brutality of the century of imperialism with open arms. As the Holy Continental Empire dug deeper into the Appalachian Mountain Republic, defeat was becoming inevitable for Powell’s fledgling state. This didn’t, however, stop the people of Appalachia from relentlessly fighting the scourge of divine destiny. It would be during the Appalachian War that some of the first ever anti-aircraft weapons were developed, with one-pounder guns being modified to shoot upwards as horse-drawn wagons carried them off to the frontlines. These early anti-aircraft guns were highly makeshift and could not turn the tides of the Appalachian War (not to mention many airships just flew at higher altitudes to evade gunfire), however, they did boost morale in an otherwise defeated state. In the end, the fall of the Appalachian Mountain Republic was unavoidable. After the ICA emerged victorious at the Battle of Bowling Green on March 3rd, 1855, the Appalachian armed forces began to capitulate, and as aerial warships began to bomb Nashville, President Lazarus W Powell decided to accept that there was no saving Appalachia and unconditionally surrendered to the Holy Continental Empire on March 8th, 1855.

The Treaty of Lexington was simple enough, and prioritized the complete integration of Appalachia into the HCE. Territory once claimed by colonial Virginia (albeit never really controlled due to the Proclamation Line of 1763) was annexed directly by the Kingdom of Virginia, whereas the remaining southern Appalachian territory that encompassed Nashville became a new Continental electorate, the Dominion of Appalachia, with Sydney Washington Lee being crowned the king of Appalachia. The quick Appalachian War was thus a decisive victory for the Holy Continental Empire, which had substantially expanded its territory and proved to the world that it was a force to be reckoned with. As increased domestic nationalism and militarization, all fueled by the fearsome flames of the Washingtonian Party, burned across the HCE, the Wars of Reconstruction were far from over. The Decade of Despair was far from over, and so too was the construction of Emperor Richard I’s envisioned Yankee Empire.

Back in Europe, the Decade of Despair had a number of effects that expanded outside of the Germanic Empire. While not leading to any immediate revolution or uprising, the proliferation of radical ideologies in this time period throughout a population of disgruntled Plebeians, was a constant theme of the Europe of the Decade of Despair. In the Roturier Kingdom of France, a new and vile ideology would be created in 1853 as the Great Crisis caused many businesses to go bankrupt. One of these businesses was a textile factory in Trier, a culturally German city within the Rhineland territory annexed into France following the Benthamian War. This particular factory was managed by Leon Heinrich Marx, who, like much of the city’s population, spoke German first and didn’t give Paris, which was keen on enforcing French culture on the region, much support. The son of Heinrich Marx, an irreligious follower of the ideals of the Enlightenment, Leon Marx had been fascinated by Enlightenment philosophy throughout much of his life, and he fused many of these ideas into his support for Rhenish nationalism during his early adulthood, participating in Rhenish secessionist newspapers and political organizations, especially during his college days.