Achille MacNamare; European Warfare in the 19th Century

The German War of 1828

Von Weber fought a holding action against the French on the first day of the Battle of Frankfurt, but retreated his exhausted forces by night. Here, the French field Marshal Devaux was faced with a quandary. Intelligence had indicated that Frankfurt itself was held by a corps-strength force of German regulars, and any pursuit of the 1st German Army would likely leave his forces exposed. If he left a corps behind to cover the city whilst chasing after the 1st German Army, there was a chance that both forces would be insufficient for the task. Ultimately, the matter was decided by King Henri, who had now joined his forces in France. He was willing to wager that the capture of Frankfurt would deal a death-blow to the new German state, and force a rethink on the parts of the traditional monarchies. So it was that Von Weber and the 1st Army were allowed to pull back to Giessen, where they would be much closer to the gathering 2nd army.

The second and third days of the Battle of Frankfurt were marked by bloody street fighting, with French soldiers having to go door to door to clear out the German defenders. Contrary to previous intelligence, rather than a corps of German regulars, the city was defended only by “Landsturm” irregulars and a handful of Landwehr. Untrained as they were, the urban environment allowed them to mount an impressive defence, and it wasn’t until the second day of the assault on the city itself that the French had extinguished most major opposition. They had taken Frankfurt at the loss of 4,000 dead and wounded, not a huge amount but a startling number considering the relative weakness of their enemies. As the French Flag was hoisted over Frankfurt’s main square, the conflict held in the balance.

The German Parliament, now on their way to Brunswick, refused to surrender, and vowed to raise more troops and push the French out. The Austrian forces crossed into Bavaria, vowing to push the French back to their own borders, and now even the British requested that the French pulled back to their borders and allow British mediation in the conflict. For Henri, this was an outrage. French opinion had been fearful of Britain’s advance in North Africa, fearing that Algeria would be used as a base to harass the south of France. Now she feared that Britain too was joining a conspiracy to build a threat on France’s Eastern Front. Henri ordered a letter to be written to the British King, stating that France would undertake action east of the Rhine until such time that she could be assured that there would be no threat to her own safety. When presented with this reply, the British government now took a strongly pro-war stance, and the new British Prime Minister pressed the king for a declaration of war against France, which was issued on the 2nd of November, 1828. It was now likely that in the new year, a British Expeditionary force would make its way to Hannover.

Following the British Declaration of War, time was of the essence for the French. Von Weber’s surviving force of 45,000 had now been augmented to around 63,000. There were another 86,000 troops under the control of the German parliament in Kassel now. The German Kings had assembled another army of 71,000 in Dresden, which was now marching to Hesse, and this would be added to an Austrian force of 170,000. If the British were able to land in the North and combine with the Hanoverian force, it could number some 54,000. Overall, this would give the anti-French coalition some 444,000 men. This would be enough to crush any number of men that the French would be able to raise, and could be more easily reinforced than the French army. To Devaux, it was his worst nightmare, and he moved quickly to strike at the divided armies to give France a better chance in the coming year. Devaux now ordered the 2nd French army to move into Hannover to oppose the British and prevent them from joining the German armies near Kassel. He ordered a 3rd French army to be created from forces covering the Italian and Spanish borders and sent to Germany. Combined, his forces would be some 319,000 strong, impressive, but not enough to withstand the coalition.

So Devaux decided to strike first, despite the onset of winter. In just four days, he marched from Frankfurt to Butzbach, where he inflicted a severe defeat on the forward defence force of the German 1st Army. Surprised and alarmed by the French advance so late in the year, Von Weber made preparations to pull back to Kassel and join the 2nd German army, but just two days after the Battle of Butzbach, the French 1st Army encountered Von Weber’s force at the Battle of Giessen. Although Von Weber’s force’s held the field until Noon, the increasing ferocity of the French attacks eventually told, and Devaux broke his centre at 12:25. Von Weber attempted to buy some time for a retreat with the Hessian Lifeguards, but these too were broken shortly after 13:30, and much of the 1st German Army was captured in an attempted retreat. With virtually the whole army killed, wounded and captured, Devaux had improved France’s odds by quite some margin. By February 1829, France’s 312,000 men faced 382,000 Germans. These were odds with which France could win with.

* * * * * *

Frederick Cregan; A History of Modern Europe

Italy's Reaction to the German War

Asti’s position had been much shaken by the events of the Venetian Revolution. Whereas prior to the Revolution, he had been seen as a progressive and anti-Austrian figure by many in Italy, he was now seen as a coward in the face of fierce Austrian resistance. The Piedmontese middle classes, who had sang his praises in 1827, now considered him to be a bulwark against progress in 1828. As the Austrians now turned to face the French in Germany, the calls in Piedmont to lead a national effort against the Austrians and establish a unified Italian Kingdom now grew stronger and stronger. On the 23rd of October, the crisis was exacerbated by the death of the Piedmontese king and the accession of Charles Emmanuel to the throne. Charles Emmanuel was suspicious of Asti and his influence over Piedmontese state and society. In light of the chaos in Europe, Charles Emmanuel also believed that to some extent, caution could be thrown into the wind, and a unified Italian state could be established.

One of Charles Emmanuel’s first acts after his coronation was the mobilization of the Piedmontese army. The Piedmontese stated that they were doing this as a defensive action in light of the war in Germany, though in reality the Piedmontese planned to push the Austrians out of Venetia, and annex the Northern Italian states. Asti quickly found himself outmanoeuvred, with the crown using popular sentiment to outflank Asti. Reluctantly, Asti threw his lot in with the Italian Nationalists, and agreed to serve as Prime Minister in the new government. By the end of December, Piedmont had around 50,000 regulars mobilized, as well as thousands of volunteer soldiers. Facing 30,000 Austrians in Venetia, there was a good chance that the Sardinian forces could make some headway. The hope of the Sardinians was that by the time the war in Germany ended, the Austrians would be exhausted, and would be forced to accept the facts on the ground.

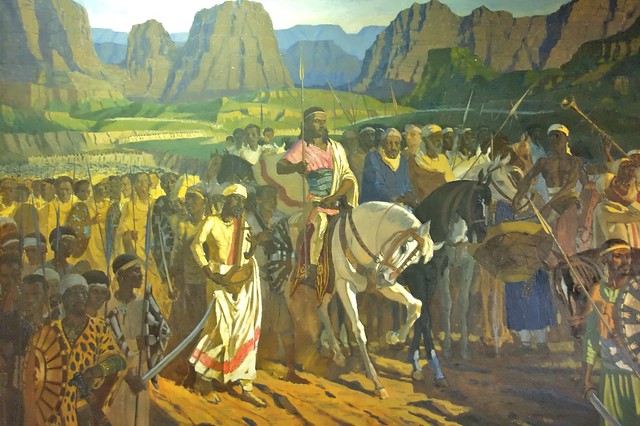

Thus, when Charles Emmanuel joined the “Army of Liberation” in Mantua, hopes were high. The Sardinian forces, as well as volunteers from further afield, marched off towards Venetia singing Italian Nationalist anthems and confident of their ability to win in the struggle ahead. This optimism seemed to be justified at the victorious battles of Verona, Montagnana and Martellago. The remaining Austrian forces pulled back at the strength of the Sardinian onslaught. Declaring victory, Charles Emmanuel left most of his forces in Venetia, and took a detachment of two divisions to force the annexations of Parma, Tuscany and Modena, all of whom were facing enormous pro-Sardinian uprisings. On the 1st of May, Charles Emmanuel officially proclaimed the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy. The army was enlarged and a liberal constitution promulgated. With events in Germany taking a turn for the worst for the Austrians, it appeared as though Italy’s day had finally arrived.

* * * * * *

Author's Notes - Back from my travels, just about getting into the swing of things and recovering form Jet Lag...

The odds are beginning to improve for France as her unity of command may prove to be her greatest advantage in the conflict. If she can prevent her opponents from uniting against her, she may win a great triumph after all in the conflict.

Piedmont in its characteristic manner has decided to try and profit from the distraction of Austria, and if France prevails in the conflict, may put Italy on the earlier road to unification. Picking a fight with a much larger state, no matter how distracted, may prove to be an enormous risk though.

Last edited: