The Arab World - 1829 to 1862

Khulood al-Shuwaikh; The Story of the Arab People

Reform and Tension in Egypt

Egypt’s disastrous war with the Ottomans showed that the world had very much left the Mamluk state behind. Her antiquated armies had been cut to pieces with ease by the Ottomans, who fought largely in the European style. The Egyptian Sultan Adel Ali, now very much fearful of his position, started an ambitious reform programme almost immediately after peace was signed. European experts in all areas of government and society were imported, as Adel Ali recognised that it was the adoption of European ways that had renewed Ottoman strength. Economically, Egypt began changing. The Nile Valley had been famed since the dawn of civilization of a place of great fertility, and French merchants suggested a new use for this agricultural potential. The cash crops which had made unimaginable amounts of wealth in the Americas in the 18th century were already grown in the Middle East, though as Egypt began to open up in the 1840s, it was cotton that quickly became the dominant crop in Egypt. It was a valuable source of foreign currency earnings, which was now necessary to pay for the import of Western arms, machines and expertise.

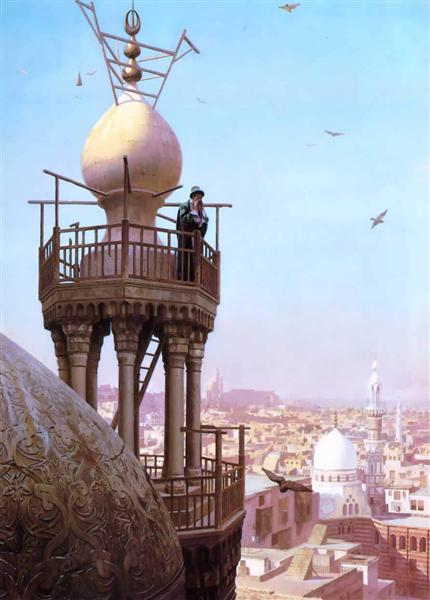

European culture however proved no less seductive than its technology and institutions. At first, an appreciation for European music, theatre and literature only touched the highest levels of Egyptian society. Egyptian society was still a conservative one, rooted deeply in Islamic tradition but for those with the means, European culture was now increasingly seen not only as desirable, but superior in some aspects. In 1853, the Sultan scandalised traditional society in Cairo by arranging for the famous Danish Opera singer Charlotte Eriksen to give a performance at the new European-style palace built on Gezira Island, which had usurped the Cairo Citadel’s position as the affluent home of the Sultan and noblemen. On the island, a new Cairo emerged, funded by the growing proceeds of the cotton trade and built in a European style, with wide boulevards and magnificent palatial houses forming a stark contrast to old Cairo, with its narrow streets and unassuming exteriors. Such a visible sign of cultural divergence did not go unnoticed by the Ulema of al-Azhar University, who began to warn against mindless imitation of Europeans.

By the beginning of the 1850s, the growing proceeds of the cotton trade were no longer enough to fuel Egypt’s development. Although export income had more than doubled in the 1840s, this was no longer enough to finance Egypt’s development. The coming of the railroad promised to open up the whole of the country economically as well as physically, and construction began on the Suez Canal in 1850. In order to pay for these new developments, capital had to come from elsewhere. Much of the money spent to construct the Suez Canal was raised on the money markets of London and Paris, where bonds for the Canal Company were also sold. The Egyptian government offered investors extraterritorial rights as well as generous tax and tariff structures, and a small community of Europeans began to settle in the cities of Cairo, Alexandria and Rashid. As much as the westernisation of the Mamluk nobility, the European community was considered a danger by the traditionalists of Egypt.

The reaction of the Coptic Christians of Egypt was somewhat more mixed. Many Coptic merchants welcomed the trade opportunities that the Europeans brought with them, and acted as intermediaries between the Muslim Landowners and the European Merchants who came to Alexandria and Rashid to purchase cotton. A number of Copts became extremely wealthy, and many of the great warehouses that dominated to coastlines of the Delta trading ports were owned by Copts. However, while the opportunities for wealth and status that the Europeans brought were welcome, missionary activities on the part of Europeans were seen as a threat by the Coptic Church. During the 1840s, conversions were still few and far between, but with the Evangelical Revival of Non-Conformist Churches of the 1850s, many missionaries went to Egypt as a source of converts. Although prevented from preaching to the Muslim population (in the open, at any rate) they found a number of converts among the Coptic communities. By the end of the 1850s, an estimated 30,000 Copts had converted to a Protestant or Reformed church, out of a Coptic population of around 600,000 overall. Some Coptic popes went as far as to petition the Sultan for a ban on missionary activities.

As the 1860s dawned, Egypt appeared to be entering a brave new world. The Suez Canal was completed in 1861, turning Egypt into a hub for international trade and making her a key strategic point. This brought the overtures of both Britain and France, who maintained colonial Empires in Asia, with both wanting to secure Egypt as an ally. However, one of the tools with which they used to curry favour with the Egyptian Government, loans, proved to be troublesome. Although the Egyptian economy was growing strongly, the growth never matched up to the increasing interest Egypt was paying to service her loans. As well as criticism from the traditionalists, the Egyptian government now began to attract criticism from modernist opposition as well, who argued that Egypt’s development was being mismanaged by the government. There were even voices which argued for a constitutional government, anathema to both the Egyptian Government and the traditionalists, but the idea began to gather momentum in the 1860s in the coffee houses of Cairo.

* * * * * *

North Africa in the Mid 19th Century

North Africa in the Mid 19th Century

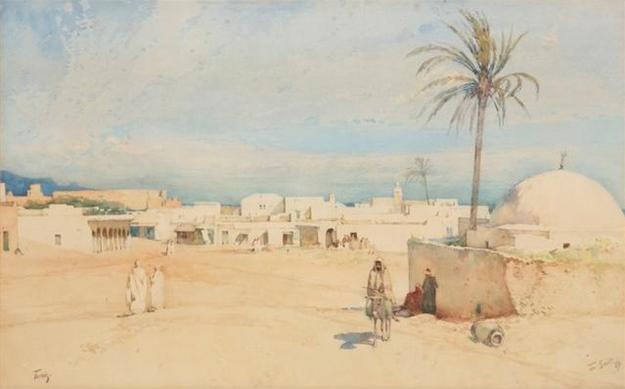

The British occupation of Algeria was the biggest shock to the Muslims of the Maghreb since the fall of al-Andalus many centuries before. Once initial fears of mass conversion and immediate expansion fell away, the rulers of the remaining countries of North Africa now considered how best to avoid the fate of the Bey of Algiers. Although piracy had greatly declined toward the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, some pirates operating from the North African coast had continued to harass the coastal peoples of Europe. Indeed, this had been one of Britain’s justifications for her adventure in Algeria. First the Sultan of Morocco, than the Bey of Tunisia and finally the Bey of Tripoli all banned piracy as well as the slave trade, though not the institution of slavery itself. There was little stomach amongst most for these measures, yet in the face of growing European power there was recognition for its necessity.

As well as reducing sources of friction with European powers, some of the North African rulers attempted to reform their states. A previous attempt at centralization in Morocco around the turn of the 17th century had resulted in some temporary success in strengthening the Sultan, the domination of the tribal peoples of Morocco became marked once Sultan Ismail bin Sharif died. Now with external pressures stronger than ever, the Moroccan Government saw it necessary to bring the tribal peoples to heel and bring a modern administrative system to the country. However, this would be an incredibly difficult task. Without the resource base of Persia and the Ottoman Empire, or the favourable geography of Egypt, the task of the Moroccan government to bring the highlands and valleys of the country under central control would be a costly struggle. Although efforts were made to improve roads and irrigation networks, as well as to foster internal trade, the majority of the efforts of the Sultan were focused on combating unrest and bringing tribal chiefs and village heads to heel.

Morocco and the rest of North Africa began to open itself up to free trade. State Monopolies were gradually abolished during the mid-19th century, opening the door for European manufactures and for the export of grain and minerals such as phosphates to Europe. The growing cities of Europe proved eager for cheap wheat from the Maghreb, though efforts by protectionists to raise prohibitive tariffs on exports hurt the exports of North African countries somewhat. Following the end of the “Grain Tariff War” in 1836 in Britain, the swiftly growing population of the British Isles grew hungry not only for Algerian grain but for foodstuffs from elsewhere in the world. Tunisia in particular made the most of the rise in demand, and its wheat exports grew threefold in the 1840s and 50s, buoyed by the increasing efficiency of agriculture in Tunisia as well as demand without. However, the export success of mineral and agricultural products in North Africa were offset by the destruction of traditional cottage industries in the region, largely due to the success of European manufactures in North Africa, which was much closer than much of the rest of the world to Europe. Cotton goods from Manchester could be produced and shipped at far less cost than those produced in Tunis or Fez. The decline of artisanal producers began to produce an urban class of underemployed who blamed the government and the Europeans for their own misfortune.

* * * * * *

The Decline of Egypt in Arabia

The Decline of Egypt in Arabia

As Egypt’s grip on its outlying territories began to weaken following the defeat in Syria, once dormant forces in Arabia began to rear their heads again. Although still too weak to challenge the Egyptian garrison at Diriyah, the Saudi family and their Wahhabi allies made their presence felt in some of the outlying oases in Arabia. The one famous exception was their defeat at the hands of the al-Alawis of Ha’il, though by the 1860s this and the Egyptian garrison in Diriyah were the only areas of Central Arabia out of the hands of the al-Saud clan. Less successful were its attempts to subjugate the Banu Khalids in al-Hasa and to stop the expansion of Oman on the rest of the coast of the Gulf. The landlocked status of the Saudi State did not seem to promise great wealth in the future, and it seemed vulnerable to the possibility renewed Egyptian strength in the region which would once again push the Saudis into exile.

In Yemen, the centrifugal forces affecting Egyptian rule were somewhat less disruptive, and there were attempts by the Egyptian administration in the region to accommodate the desires of the Yemenis. The Zayidi Imam of Yemen had been unseated by Egyptian forces, but now his grandson was invited to return and rule under Egyptian supervision, as a concession to the Zayidi population of North Yemen. The Egyptians concentrated on concentrating direct rule on the key ports in Yemen, Aden and Mocha. These were important ports in funnelling many of the luxuries of Asia into the Red Sea and into Egypt, making them valuable sources of income for the Egyptians. Although their importance to the Egyptian economy began to decline as the export of cotton to Europe became ever more important, they maintained a strategic importance as the Suez Canal was built, serving as bases to fight piracy on the Horn of Africa and refuelling stations for ships coming from the Indian Ocean and beyond into Europe. This growth in traffic in the 1860s was fast making Aden a surprisingly cosmopolitan place.

The impact of modern technology was also beginning to make itself felt even in the Hedjaz, the home of the Prophet. The Hashemite Dhawu-'Awn clan ruled the area as they had done for centuries, though with their de jure Egyptian masters increasingly distant and weak. However, the Hashemites remained loyal to the Egyptian Sultan, instead making the first steps toward imposing some kind of modern authority in the region. The steam ship now began to bring pilgrims from further afield to Jeddah, increasing the numbers in the annual Hajj pilgrimage and providing the Hashemites with a slight increase in revenue. Much of the increase went into the creation of militarised police force to protect pilgrims and other inhabitants of the region from the Bedouin, who were loath to recognise any authority and who saw brigandage as their birthright. The 1850s were marked by the increasing efforts of the Hashemites to protect pilgrims against the bandits who had so often targeted those making the sacred journey to Mecca and Medina.

* * * * * *

Author's Notes - With the defeat of Egypt at the hands of the Ottomans, and the growth of European influence in the Arab World, change is coming at an ever faster rate. Tensions between the modernisers and the traditionalists in much of the Arab world are likely to play an ever more important role in the politics of the region, though it remains to be seen how Europeans will react to any challenges that they face in the region.