You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Birth and Rise of the New Republic: a Brazilian TL

- Thread starter Vinization

- Start date

John Fredrick Parker

Donor

Hm, well presumably with the left and right being flipped - so two candidates on the left and one on the right (and I think we all can already guess who they are) emerge as the top three; the runoff comes down to the guy on the right and one if the guys on the left; and in a narrow result, the remaining left one wins.Minor spoilers: In this TL, it is common for Brazilian political and academic circles to state that the 1990 Peruvian presidential election is an almost perfect replica of the 1989 Brazilian presidential election.

So the question is - will the next president be Lula or Brizola? I think we know our author’s personal preferences, but he may still surprise us.

It is safe to say that the next update will be much shorter than the last. It will be about a "war" between two old guys who were supposed to retire quite some time ago, but insisted on staying in electoral politics long after they've passed their prime. A rather damning indictment of said country's political system.

i have just finished adding threadmarks to all of this TL's chapters. Should be faster and easier to read now, without having to scroll through stuff.

John Fredrick Parker

Donor

So re-reading this recently, I recall you have the UK Labour Party chose Healy instead of Foot for Leader, then performing better in 1983 than they had in OTL... but still, I found, losing seats. This would mean there was likely still another leadership election after said general, right?

Andean Snapshot: Una Pelea de Viejos

------------------

Andean Snapshot: Una Pelea de Viejos

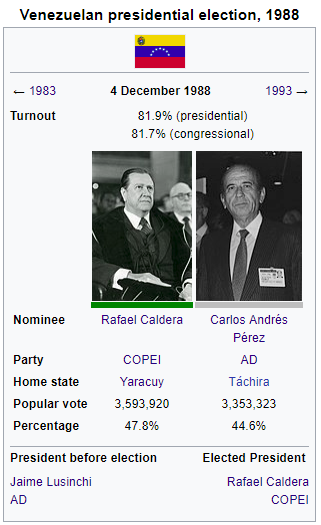

Out of all the countries in South America, Venezuela was quite possibly the only one whose democracy remained stable in the sixties and seventies. Well, at least after said democracy was restored following the ten-year long (1948-1958) dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez, who was overthrown in a bloodless coup d'état. After the restoration of democracy, the two main parties of the time, which were the center-right christian democratic COPEI, led by Rafael Caldera and the social democratic AD (Acción Democrática, Democratic Action), led by the legendary president Rómulo Betancourt (known as the Father of Venezuelan Democracy), signed a power sharing agreement known as the Punto Fijo Pact. There was a third party, the URD (Democratic Republican Union) that also participated in the negotiations, but it decayed over the years, ensuring that COPEI and AD would dominate Venezuelan politics for decades to come.

From left to right, the three men who signed the Punto Fijo Pact: Rafael Caldera (COPEI), Rómulo Betancourt (AD) and Jóvito Villalba (URD).

From left to right, the three men who signed the Punto Fijo Pact: Rafael Caldera (COPEI), Rómulo Betancourt (AD) and Jóvito Villalba (URD).

The Punto Fijo Pact was a double edged sword. On the plus side, it ensured that Venezuelan democracy remained stable, and the country was safe from the military coups and severe internal conflicts that plagued most of its neighbors. This put Venezuela in the perfect position to take advantage of the sudden rise in oil prices that occurred in the seventies and early eighties, with the gigantic revenues extracted from PDVSA (the state oil company) being used to fund ambitious infrastructure projects and social programs, and turning it into the richest country in South America. However, the Pact also created a highly exclusionary political system, with AD and COPEI maintaining a stranglehold onto power and not letting anyone else get it.

This not only allowed corruption to take hold, a problem that only grew as time went on, but also greatly limited the pool of potential leaders that the country had. These issues were at first masked by the economic boom of the 1970s, but became impossible to ignore during the second half of the following decade as Venezuela's explosive economic growth began to wear out. By the presidential election year of 1988, the country was on the verge of a severe economic and political crisis. Speaking of crises, the election's two main contenders were almost literally the personification of everything was wrong with Venezuela's fossilised political system.

These candidates were former presidents Carlos Andrés Pérez (AD) and Rafael Caldera (COPEI). Not only they had already occupied their nation's highest post (and were quite popular and succesful during their terms, one must add) they were also very, very old: Caldera, whose term lasted from 1969 to 1974, was 72 years old, and CAP, who ran the country from 1974 to 1979, was 66 years old. The race, although tight, was quite boring, and some newspapers, including a few foreign ones, called the election a "quarrel between two old geezers" ("una pelea de viejos"), mocking the flaws of the Punto Fijo system.

In the end, Caldera prevailed by a small margin, due to the fact that CAP's campaign suffered from allegations of corruption during his term, and that there were several irrelevant left-wing candidates that acted as spoilers, preying on voters that would normally go to AD. The system would linger on for a few more years, and its inevitable collapse would usher in a tumultuous new period in Venezuela's history.

Andean Snapshot: Una Pelea de Viejos

Out of all the countries in South America, Venezuela was quite possibly the only one whose democracy remained stable in the sixties and seventies. Well, at least after said democracy was restored following the ten-year long (1948-1958) dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez, who was overthrown in a bloodless coup d'état. After the restoration of democracy, the two main parties of the time, which were the center-right christian democratic COPEI, led by Rafael Caldera and the social democratic AD (Acción Democrática, Democratic Action), led by the legendary president Rómulo Betancourt (known as the Father of Venezuelan Democracy), signed a power sharing agreement known as the Punto Fijo Pact. There was a third party, the URD (Democratic Republican Union) that also participated in the negotiations, but it decayed over the years, ensuring that COPEI and AD would dominate Venezuelan politics for decades to come.

The Punto Fijo Pact was a double edged sword. On the plus side, it ensured that Venezuelan democracy remained stable, and the country was safe from the military coups and severe internal conflicts that plagued most of its neighbors. This put Venezuela in the perfect position to take advantage of the sudden rise in oil prices that occurred in the seventies and early eighties, with the gigantic revenues extracted from PDVSA (the state oil company) being used to fund ambitious infrastructure projects and social programs, and turning it into the richest country in South America. However, the Pact also created a highly exclusionary political system, with AD and COPEI maintaining a stranglehold onto power and not letting anyone else get it.

This not only allowed corruption to take hold, a problem that only grew as time went on, but also greatly limited the pool of potential leaders that the country had. These issues were at first masked by the economic boom of the 1970s, but became impossible to ignore during the second half of the following decade as Venezuela's explosive economic growth began to wear out. By the presidential election year of 1988, the country was on the verge of a severe economic and political crisis. Speaking of crises, the election's two main contenders were almost literally the personification of everything was wrong with Venezuela's fossilised political system.

These candidates were former presidents Carlos Andrés Pérez (AD) and Rafael Caldera (COPEI). Not only they had already occupied their nation's highest post (and were quite popular and succesful during their terms, one must add) they were also very, very old: Caldera, whose term lasted from 1969 to 1974, was 72 years old, and CAP, who ran the country from 1974 to 1979, was 66 years old. The race, although tight, was quite boring, and some newspapers, including a few foreign ones, called the election a "quarrel between two old geezers" ("una pelea de viejos"), mocking the flaws of the Punto Fijo system.

In the end, Caldera prevailed by a small margin, due to the fact that CAP's campaign suffered from allegations of corruption during his term, and that there were several irrelevant left-wing candidates that acted as spoilers, preying on voters that would normally go to AD. The system would linger on for a few more years, and its inevitable collapse would usher in a tumultuous new period in Venezuela's history.

This has to be the smallest update I've ever written so far, so I apologize. In the next update we'll go back to Brazil and check out how a couple of mayors are doing and how tough their job is right now.

John Fredrick Parker

Donor

Will we also get into the next Brazilian Presidential Election, or is the wait for that longer?In the next update we'll go back to Brazil and check out how a couple of mayors are doing and how tough their job is right now.

We've still got the 1988 mayoral elections to look at. And since those are going to involve a few interesting characters, I'll almost certainly have to divide them into separate parts. Rest assured though, it definitely won't be as many parts as the 1986 gubernatorial elections.Will we also get into the next Brazilian Presidential Election, or is the wait for that longer?

Part 8: Migraines

------------------

Part 8: Migraines

May 18, 1987

Niterói, RJ, Federative Republic of Brazil

In spite of being just 34 years old, the mayor of Niterói, Jorge Roberto Silveira, could be considered anything but a political newbie, with two of his older relatives reaching the state's highest executive post. His father, Roberto Silveira, was governor until he suffered a tragic and early death in a helicopter accident when Jorge was just 5 years old, and his uncle, Badger da Silveira, was deposed during the 1964 coup d'état for the "crime" of belonging to PTB. With politics being something that was almost literally in his blood, it was no surprise that he eventually ran for office, winning a seat in the state assembly in 1978. What did shock most of the people who knew him was his decision to run for the mayoralty of Niterói in 1982, despite having very little political experience (four years as an assemblyman, along with his family connections to PTB members). He won the election in an upset, being carried by governor-elect Leonel Brizola's very extensive coattails (1).

His victory immediatly made him a potential contender in the race to succeed governor Darcy Ribeiro in 1990, and he would be damned if he didn't at least try to run and run an administration that would make his father and uncle proud.

Hooray!

All he had to do in order to make his dream a reality was to administrate one of Rio's largest cities.

After said city was ruled for years by a certain Wellington Moreira Franco, who wasn't a good administrator, to put it mildly (2).

In the middle of one of the worst recessions Brazil had ever seen, which obviously diminished whatever aid Jorge could get from the federal government.

Add a very high unemployment rate.

Shit.

Uhhhh...

To say that he had no idea of the sheer enormity of the task ahead of him would the mother of all understatements. He suddenly found himself having to work 18 hours a day, constantly having to make deals with the city council (PTB was the largest party, but it didn't have a majority) to make sure he could pass bills, and, most importantly, not shoot his budgets down. What he hated the most about his new job, by far, was the fact that he constantly had to pretty much beg for each and every single available penny of aid from the state and federal governments, just to make sure Niterói's economy didn't fall apart. It didn't help that governor Brizola was more than a little hard to work with, since the Old Caudillo was almost obsessed with ensuring that every single PTB administration in the country had to be absolutely perfect, and Niterói's political importance ensured that Silveira had no choice but put up with the gaúcho's constant and often excessive attention (3).

Fortunately, he got used to his new schedule and all of its hardships after the first few years. The situation actually improved after 1986, as not only Darcy Ribeiro was far easier to work with than Brizola was (he didn't have any presidential ambitions), he also no longer had to worry about the horrifiying possibility of Moreira Franco becoming the state governor. Thanks to his hard work (and factors that were completely outside the young mayor's control), Niterói's financial outlook was not as desperate as it was when Silveira took over, and his newly earned experience would greatly help him in the not so distant future.

Still, he knew that the even the biggest problems he faced were nothing when compared to what countless other mayors around the country had to deal with.

He always knew.

------------------

November 8, 1987

São Paulo, SP, Federative Republic of Brazil

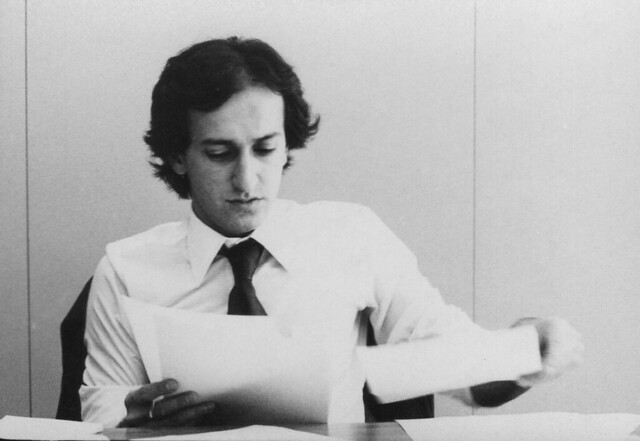

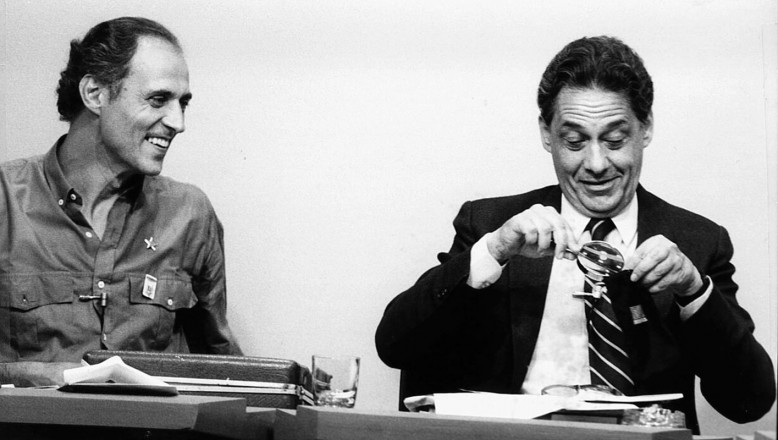

Fernando Henrique Cardoso, mayor of São Paulo, felt like his head was about to explode. He had felt that many times since he took control of the mayoralty, but even then he just couldn't get used to all this stress.

A very big job for just one man.

Nobody could.

Seriously, how could have been so stupid? He was a fucking senator! He should have known that and economic crisis was imminent, and that governing the largest city in Brazil in the middle of such an economic and political hurricane was a terrible idea. Had he stayed in the Senate, he would've probably won a second term during the elections that occurred last year, and even if he didn't, he could've run for another office later. Oh well. Now he was stuck here, and everyone around him was either a potential or open enemy of his.

That wasn't a joke. First, his refusal to support Orestes Quércia's gubernatorial candidacy in 1986 earned him the ire of PMDB's conservative wing (he supported Mário Covas, a progressive, and didn't campaign during the general election) and effectively isolated him from whatever aid he could get from the federal government. Second, he had to contend with an enormously ambitious and hostile governor, who would no doubt do everything in his power to ensure that FHC was succeeded by one of his allies in 1988. Third, the City Council was divided into several factions, thanks to the fact that PMDB was on the verge of falling apart, and each of these groups wanted some concession from the mayoral government.

Mayor Fernando Henrique his close ally, the then state governor Franco Montoro.

Speaking of factions and falling apart, Fernando Henrique, like many of his fellow progressive peemedebistas, had no intentions of staying in his current party for much longer. Still, he wasn't sure of just where exactly did he want to go. The first and most obvious choice would be to follow his rebellious companions, like Franco Montoro, Geraldo Alckmin, José Serra, and so many others, and found an entirely new party. Another path would be to instead join PT, since he was not only a close friend of Lula, but was also already close to the party as a whole, thanks to his (mostly) loyal deputy mayor, Eduardo Suplicy. Such an option would also be safer, since it would take time for Covas' hypothetical new party to solidify, and PT already had some (somewhat) decent infrastructure.

The only thing that he was absolutely sure of at the moment is that he would never run for any executive office ever again. Let others, like that Celso Daniel guy, do that. FHC was would serve his country (and himself) far better as a senator or, who knows, maybe even a cabinet minister someday (4).

------------------

Notes:

(1) IOTL, Silveira was reelected to the State Assembly (Alerj), became a member of governor Brizola's cabinet, and won the Niterói mayoralty in 1988. Here, he is emboldened by a stronger, united PTB combined a very favourable climate for opposition candidates, and runs for mayor six years early. He barely wins thanks to the bound vote.

(2) No comment.

(3) Brizola really wanted to be president, and he was very much aware that 1989 was probably his last decent chance to do that. Considering that IOTL he stayed in politics presiding PDT until he died in 2004 (he was 82 years old) it's probably safe to say that he earned his nickname for a reason.

(4) That's exactly what you read right there. FHC's not gonna run for the presidency anytime soon, or ever.

Part 8: Migraines

May 18, 1987

Niterói, RJ, Federative Republic of Brazil

In spite of being just 34 years old, the mayor of Niterói, Jorge Roberto Silveira, could be considered anything but a political newbie, with two of his older relatives reaching the state's highest executive post. His father, Roberto Silveira, was governor until he suffered a tragic and early death in a helicopter accident when Jorge was just 5 years old, and his uncle, Badger da Silveira, was deposed during the 1964 coup d'état for the "crime" of belonging to PTB. With politics being something that was almost literally in his blood, it was no surprise that he eventually ran for office, winning a seat in the state assembly in 1978. What did shock most of the people who knew him was his decision to run for the mayoralty of Niterói in 1982, despite having very little political experience (four years as an assemblyman, along with his family connections to PTB members). He won the election in an upset, being carried by governor-elect Leonel Brizola's very extensive coattails (1).

His victory immediatly made him a potential contender in the race to succeed governor Darcy Ribeiro in 1990, and he would be damned if he didn't at least try to run and run an administration that would make his father and uncle proud.

Hooray!

All he had to do in order to make his dream a reality was to administrate one of Rio's largest cities.

After said city was ruled for years by a certain Wellington Moreira Franco, who wasn't a good administrator, to put it mildly (2).

In the middle of one of the worst recessions Brazil had ever seen, which obviously diminished whatever aid Jorge could get from the federal government.

Add a very high unemployment rate.

Shit.

Uhhhh...

To say that he had no idea of the sheer enormity of the task ahead of him would the mother of all understatements. He suddenly found himself having to work 18 hours a day, constantly having to make deals with the city council (PTB was the largest party, but it didn't have a majority) to make sure he could pass bills, and, most importantly, not shoot his budgets down. What he hated the most about his new job, by far, was the fact that he constantly had to pretty much beg for each and every single available penny of aid from the state and federal governments, just to make sure Niterói's economy didn't fall apart. It didn't help that governor Brizola was more than a little hard to work with, since the Old Caudillo was almost obsessed with ensuring that every single PTB administration in the country had to be absolutely perfect, and Niterói's political importance ensured that Silveira had no choice but put up with the gaúcho's constant and often excessive attention (3).

Fortunately, he got used to his new schedule and all of its hardships after the first few years. The situation actually improved after 1986, as not only Darcy Ribeiro was far easier to work with than Brizola was (he didn't have any presidential ambitions), he also no longer had to worry about the horrifiying possibility of Moreira Franco becoming the state governor. Thanks to his hard work (and factors that were completely outside the young mayor's control), Niterói's financial outlook was not as desperate as it was when Silveira took over, and his newly earned experience would greatly help him in the not so distant future.

Still, he knew that the even the biggest problems he faced were nothing when compared to what countless other mayors around the country had to deal with.

He always knew.

------------------

November 8, 1987

São Paulo, SP, Federative Republic of Brazil

Fernando Henrique Cardoso, mayor of São Paulo, felt like his head was about to explode. He had felt that many times since he took control of the mayoralty, but even then he just couldn't get used to all this stress.

A very big job for just one man.

Nobody could.

Seriously, how could have been so stupid? He was a fucking senator! He should have known that and economic crisis was imminent, and that governing the largest city in Brazil in the middle of such an economic and political hurricane was a terrible idea. Had he stayed in the Senate, he would've probably won a second term during the elections that occurred last year, and even if he didn't, he could've run for another office later. Oh well. Now he was stuck here, and everyone around him was either a potential or open enemy of his.

That wasn't a joke. First, his refusal to support Orestes Quércia's gubernatorial candidacy in 1986 earned him the ire of PMDB's conservative wing (he supported Mário Covas, a progressive, and didn't campaign during the general election) and effectively isolated him from whatever aid he could get from the federal government. Second, he had to contend with an enormously ambitious and hostile governor, who would no doubt do everything in his power to ensure that FHC was succeeded by one of his allies in 1988. Third, the City Council was divided into several factions, thanks to the fact that PMDB was on the verge of falling apart, and each of these groups wanted some concession from the mayoral government.

Mayor Fernando Henrique his close ally, the then state governor Franco Montoro.

Speaking of factions and falling apart, Fernando Henrique, like many of his fellow progressive peemedebistas, had no intentions of staying in his current party for much longer. Still, he wasn't sure of just where exactly did he want to go. The first and most obvious choice would be to follow his rebellious companions, like Franco Montoro, Geraldo Alckmin, José Serra, and so many others, and found an entirely new party. Another path would be to instead join PT, since he was not only a close friend of Lula, but was also already close to the party as a whole, thanks to his (mostly) loyal deputy mayor, Eduardo Suplicy. Such an option would also be safer, since it would take time for Covas' hypothetical new party to solidify, and PT already had some (somewhat) decent infrastructure.

The only thing that he was absolutely sure of at the moment is that he would never run for any executive office ever again. Let others, like that Celso Daniel guy, do that. FHC was would serve his country (and himself) far better as a senator or, who knows, maybe even a cabinet minister someday (4).

------------------

Notes:

(1) IOTL, Silveira was reelected to the State Assembly (Alerj), became a member of governor Brizola's cabinet, and won the Niterói mayoralty in 1988. Here, he is emboldened by a stronger, united PTB combined a very favourable climate for opposition candidates, and runs for mayor six years early. He barely wins thanks to the bound vote.

(2) No comment.

(3) Brizola really wanted to be president, and he was very much aware that 1989 was probably his last decent chance to do that. Considering that IOTL he stayed in politics presiding PDT until he died in 2004 (he was 82 years old) it's probably safe to say that he earned his nickname for a reason.

(4) That's exactly what you read right there. FHC's not gonna run for the presidency anytime soon, or ever.

Unfortunately, this will be my last update in a while, since my university duties are devouring my free time once again.

As always, comments and constructive criticism are appreciated.

As always, comments and constructive criticism are appreciated.

John Fredrick Parker

Donor

With the latest update stating that FHC isn’t running for President, that throws a bit of a wrench into this theory for me.Hm, well presumably with the left and right being flipped - so two candidates on the left and one on the right (and I think we all can already guess who they are) emerge as the top three; the runoff comes down to the guy on the right and one if the guys on the left; and in a narrow result, the remaining left one wins.

So the question is - will the next president be Lula or Brizola? I think we know our author’s personal preferences, but he may still surprise us.

Part 9: The Citizens' Constitution

It lives!

------------------

Part 9: The Citizens' Constitution

February 5, 1987

Chamber of Deputies, National Congress Building, Brasília, Federative Republic of Brazil

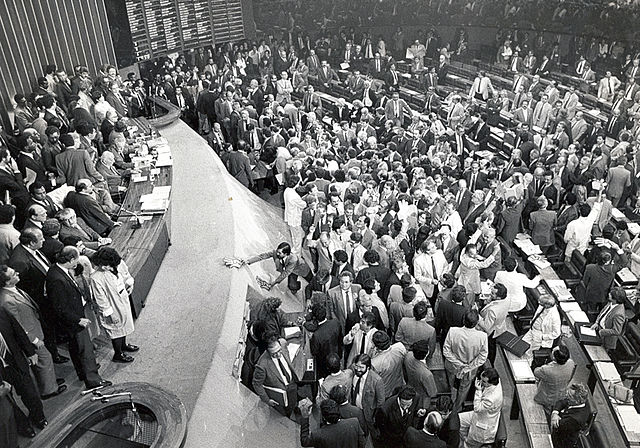

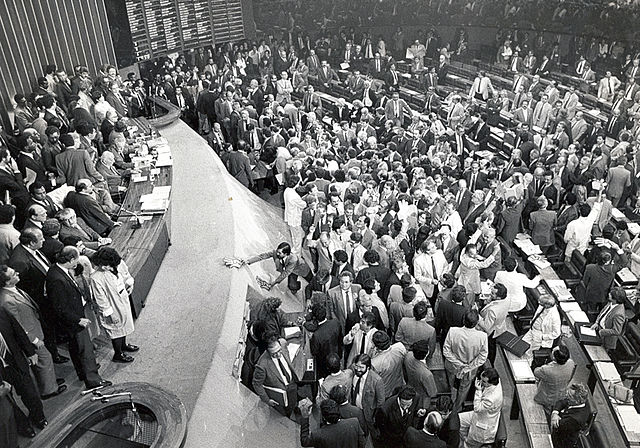

It was a busy, loud day in the Chamber of Deputies. Well, more so than usual. You see, Brazil's legislators, both deputies and senators, were returning from their parliamentary recess, which ended four days ago. For the many new figures who rose to prominence thanks to last year's election, it was their first chance to take over their newly acquired seats and do the jobs the people elected them to do. However, that wasn't the reason for all of the hubhub. These people weren't supposed to just vote on a bunch of stuff, no, their job was far more important than that. They were going to write the newly reborn democracy's Contitution.

This obviously meant that their decisions and actions would affect Brazil for decades to come. There was just one question remaining, though: who was going to preside over which chamber and, most importantly, the whole thing? In the Senate, dominated by the Centrão (right wing) despite the gains the Progressive Bloc made in last year's elections, conservative Milton Cabral (PDS-PB) became president of the upper house without much difficulty. The situation was a little trickier in the lower house, where, after two rounds, progressive Lysâneas Maciel (PTB-RJ) defeated Inocêncio Oliveira (PFL-PE) by a narrow margin of 23 votes. The only question that now remained was who was going to get the juiciest prize of them all: the presidency of the Constituent Assembly, which would be decided by both houses at once.

The whole ordeal was, uh, well... a shitshow.

Some things just never change, do they?

Some things just never change, do they?

There was really no better word to describe the situation. First, the two contenders. The Centrão's candidate was Luiz Henrique da Silveira (PMDB-SC), who was quite conservative by his party's standards, while the Progressive Bloc's candidate was none other than Lysâneas Maciel, who already held the presidency of the Chamber of Deputies. The whole process, in which the electors' names and choices were kept secret, was full of allegations of foul play, with Maciel being accused of using his position to bribe or threaten people into voting for him, while Silveira was accused of trying to violate the chamber's electronic panel. The election dragged for much longer than anticipated, since the first vote was annulled thanks to accusations of fraud made by both sides.

By then, protesters started to gather outside the National Congress, condemning the shameful spectacle, and every political heavyweight in the country went to Brasília to make sure his side won the vote. Governors, mayors, party bosses, student leaders, union chiefs, big businessmen, landowners, you name it.

Rio governor Darcy Ribeiro with deputy Mário Juruna (PTB-RJ), Brazil's first and, so far, only native congressman. Juruna, a member of the Xavante ethnicity, was first elected to Congress in 1982 and served four more terms, until his death from diabetes in 2002 (1).

Rio governor Darcy Ribeiro with deputy Mário Juruna (PTB-RJ), Brazil's first and, so far, only native congressman. Juruna, a member of the Xavante ethnicity, was first elected to Congress in 1982 and served four more terms, until his death from diabetes in 2002 (1).

After a couple more agonizingly long days of bickering, a new vote was finally held. Here are the results:

Lysâneas Maciel -- 277 votes

Lysâneas Maciel -- 277 votes

Luiz Henrique da Silveira -- 274 votes

Luiz Henrique da Silveira -- 274 votes

There were also eight voters that didn't to show up.

At first, the Silveira camp wanted to challenge the results, since they were so ridiculously close, but the election had dragged on for so long that both sides were completely exhausted, and everyone was just happy that it was all over At last, on February 8, a whole week after it was originally supposed to function, the Constituent Assembly began the long and arduous work that was the creation of Brazil's new constitution. However, before even a single article was voted on, there was one thing that was crystal clear to all of the Assembly's participants, and that was the fact that, much to president Ulysses' despair, PMDB was on the verge of falling apart. Indeed, had the party's parliamentary wing gone entirely to one direction or another, either Maciel or Siveira would have scored an unquestionable, decisive victory. Instead, PMDB fractured itself right in the middle, and the Assembly would now be plagued by endless bickering between two sides with roughly equal power (2).

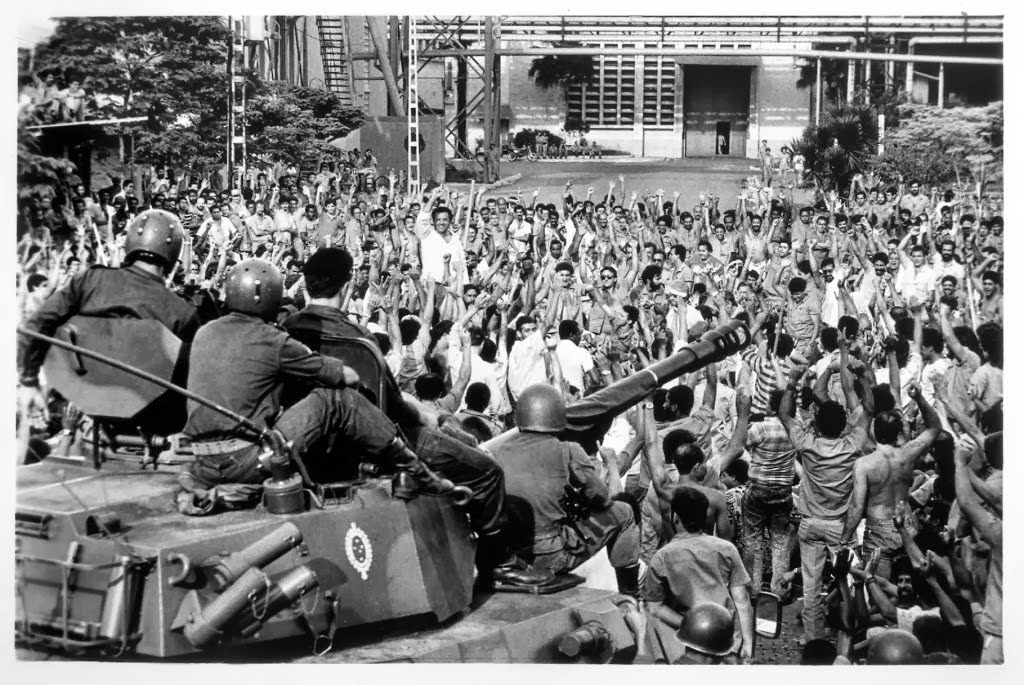

In June 25th, 1988, while the Constitution's articles were still being voted on, the inevitable happened: PMDB's progressive wing broke away from the main party, and founded a new group, the PSDB (Brazilian Social Democratic Party). Unlike most of its contemporaries, which started out small and later grew larger (such as PT and PTB), PSDB already had, right after its founding, forty one deputies, six senators and one state governor (Minas Gerais' Itamar Franco). With a toucan as its main symbol, it was created to be a center-left, moderate party, and its most important members were presitigious politicians like senators Mário Covas (who became PSDB's first president) and José Richa, deputies such as José Serra, Geraldo Alckmin, Ciro Gomes and Pimenta da Veiga, and other important figures such as former São Paulo governor Franco Montoro. Brazil would soon find out in that year's municipal elections if this new party's "natural bigness" (probably not a real word, sorry) really meant anything.

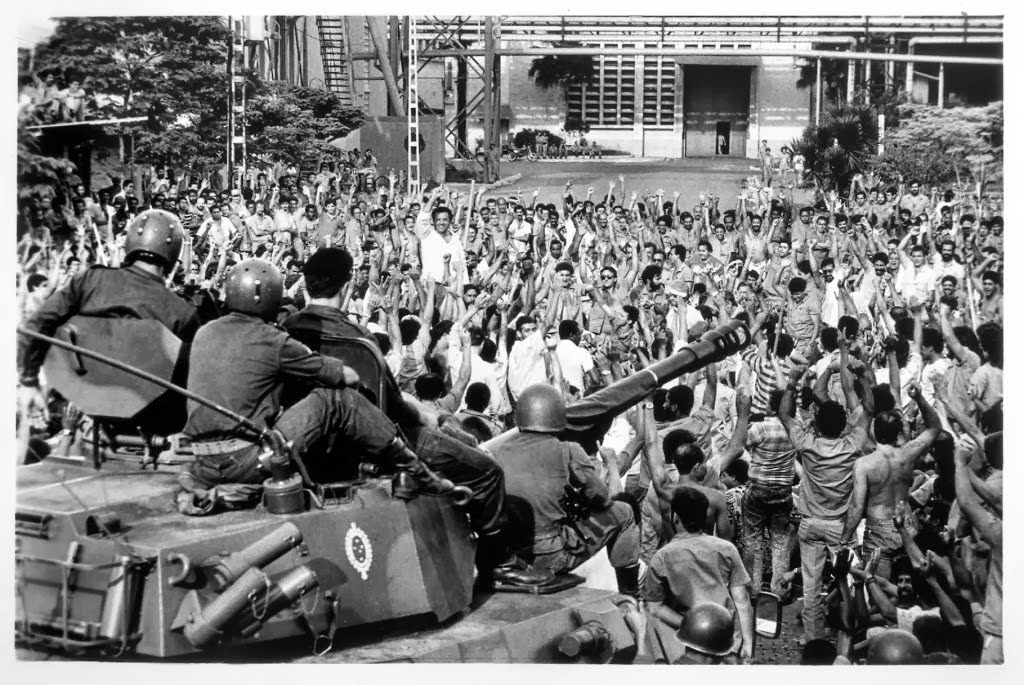

The founding members of PSDB.

Unfortunately, thanks to events largely outside their control, the tucanos ultimately failed to truly get the attention of the media, at least for now. The reality was that the creation of PSDB didn't really change the balance of power in the legislature or the Constituent Assembly, since they were already siding with the leftists in Congress to begin with. Plus, there were much juicier stories to report on, like the occasional fistfights that plagued the Assembly and the ever more frequent strikes that crippled the national economy and, in one tragic case that occurred in the industrial city of Volta Redonda (RJ), ended in a confrontation with the army that resulted in the death of three workers and around fifty more wounded (3). This event, combined with the recession which, while not as bad as it had been in 86 and 87, still refused to go away, and the utter collapse of PMDB in the municipal elections of November 15, made it so that the federal government reached the peak of its unpopularity. In a poll conducted by IBOPE that was released in December 1988, it was revealed that only 15% of the Brazilian population still had a favourable view of the administration headed by president Ulysses Silveira Guimarães (4).

Soldiers on a tank facing striking ironworkers in Volta Redonda before all hell broke loose.

Those stories were all from the domestic front, and there was no shortage of other interesting things happening around the globe. Argentina, Brazil's big southern neighbor, defeated a coup d'état attempt thanks to president Raúl Alfonsín's veto of the full stop law (Ley de Punto Final), which would've ended prosecutions against agents of the old military dictatorship that were not already in jail (5). In the north, the Perfect Dictatorship that ruled Mexico for 59 years finally collapsed, and in the United States, president Ronald Reagan resigned in disgrace thanks to a scandal whose was scale comparable to Watergate. In Asia, several dictators in the Far East were toppled by popular revolutions, and in the Middle East, Iraq ceased to exist as a functional state after its ruler, Saddam Hussein, was overthrown and executed after being soundly defeated by Iran, something that put all Arab nations in high alert (6).

...Wait a minute, we're yet to talk about the new Constitution. I must apologise, for I rushed things a bit. Anyway, back to Brasília!

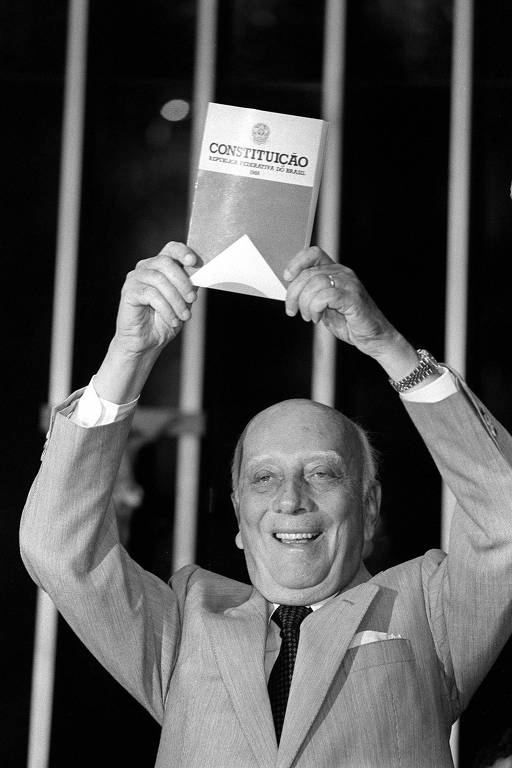

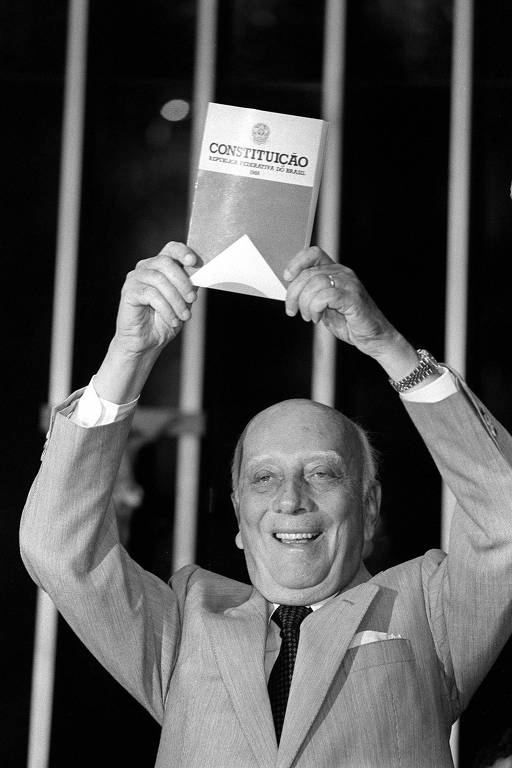

Finally, after a year and a half of arguing, voting, one or two fistifights, and more arguing, the new Brazilian Constitution was fully elaborated and was unanimously promulgated by both houses of Congress in one final triumphant session. Lysâneas Maciel, who presided over the whole process, finished it with an emotional and truly memorable speech that was broadcasted to the entire country. He proudly declared the complete hatred and revulsion he felt towards any kind of dictatorship, especially the ones that plundered and butchered Latin America for so many years. At long last, he finished, Brazil, through its new national charter, was ready to cast that hideous spectre to the dustbin of history, and that the long night that started in 1964 finally came to an end. The standing ovation he received lasted at least five minutes, and after that, all lawmakers in the chamber held their hands together and sang the Brazilian National Anthem.

Here are some of the new Constitution's articles, in no particular order:

Hundreds of rural labourers protesting for social justice. This photo was taken in the 1960s, by the way.

Hundreds of rural labourers protesting for social justice. This photo was taken in the 1960s, by the way.

The new supreme law was with no doubt the most democratic of all the constitutions that Brazil had. Thanks to that, and the context it was written in, it was given a most kind and deserving nickname: Constituição Cidadã, the Citizen's Constitution.

President Ulysses could not be happier. He couldn't care less about his and PMDB's unpopularity, that was irrelevant. What truly mattered was the fact that now, after 21 years of darkness, his beloved country was finally free to choose its own destiny. This was the best day of his life.

------------------

Notes:

(1) IOTL, Juruna ran for reelection in 1986, but was defeated. He then ran for a seat in the Chamber of Deputies in 1990 and 1994, losing both times. Finally, he died a depressed and forgotten man, a fate which he absolutely did not deserve.

(2) This is a very big difference. IOTL, the Constituent Assembly was almost completely dominated by the Centrão, thanks to the PMDB landslide of 1986.

(3) As OTL.

(4) Poor guy. Still, at least that's higher than José Sarney's 7%. After all, he didn't deceive his people with a shoddy economic plan, so there's that.

(5) I might be mistaken here, but I believe Alfonsín was initially opposed to this law IOTL, only later changing his opinion due to the possibility of a coup. Here, he decides that is a tolerable risk to ensure that all of the thugs who worked for the Proceso de Reorganinización Nacional go to prison. Naturally, such a course of action has its consequences.

(6) Spoiler alert! Spoiler alert!

(7) The president was originally forbidden from running for a second term IOTL. Didn't matter much, since president Fernando Henrique Cardoso bribed Congress into passing a reelection amendment.

(8) The federal government is supposed to do that IOTL, but only if said land doesn't "execute its social function" or something like that. This creates a loophole that ensures that this legislation impossible to enforce. Here, since there's an awful lot more leftists in the Constituent Assembly, that doesn't happen, to the ire of latifundiários like Kátia Abreu, Blairo Maggi and Ronaldo Caiado.

------------------

Part 9: The Citizens' Constitution

February 5, 1987

Chamber of Deputies, National Congress Building, Brasília, Federative Republic of Brazil

It was a busy, loud day in the Chamber of Deputies. Well, more so than usual. You see, Brazil's legislators, both deputies and senators, were returning from their parliamentary recess, which ended four days ago. For the many new figures who rose to prominence thanks to last year's election, it was their first chance to take over their newly acquired seats and do the jobs the people elected them to do. However, that wasn't the reason for all of the hubhub. These people weren't supposed to just vote on a bunch of stuff, no, their job was far more important than that. They were going to write the newly reborn democracy's Contitution.

This obviously meant that their decisions and actions would affect Brazil for decades to come. There was just one question remaining, though: who was going to preside over which chamber and, most importantly, the whole thing? In the Senate, dominated by the Centrão (right wing) despite the gains the Progressive Bloc made in last year's elections, conservative Milton Cabral (PDS-PB) became president of the upper house without much difficulty. The situation was a little trickier in the lower house, where, after two rounds, progressive Lysâneas Maciel (PTB-RJ) defeated Inocêncio Oliveira (PFL-PE) by a narrow margin of 23 votes. The only question that now remained was who was going to get the juiciest prize of them all: the presidency of the Constituent Assembly, which would be decided by both houses at once.

The whole ordeal was, uh, well... a shitshow.

There was really no better word to describe the situation. First, the two contenders. The Centrão's candidate was Luiz Henrique da Silveira (PMDB-SC), who was quite conservative by his party's standards, while the Progressive Bloc's candidate was none other than Lysâneas Maciel, who already held the presidency of the Chamber of Deputies. The whole process, in which the electors' names and choices were kept secret, was full of allegations of foul play, with Maciel being accused of using his position to bribe or threaten people into voting for him, while Silveira was accused of trying to violate the chamber's electronic panel. The election dragged for much longer than anticipated, since the first vote was annulled thanks to accusations of fraud made by both sides.

By then, protesters started to gather outside the National Congress, condemning the shameful spectacle, and every political heavyweight in the country went to Brasília to make sure his side won the vote. Governors, mayors, party bosses, student leaders, union chiefs, big businessmen, landowners, you name it.

After a couple more agonizingly long days of bickering, a new vote was finally held. Here are the results:

There were also eight voters that didn't to show up.

At first, the Silveira camp wanted to challenge the results, since they were so ridiculously close, but the election had dragged on for so long that both sides were completely exhausted, and everyone was just happy that it was all over At last, on February 8, a whole week after it was originally supposed to function, the Constituent Assembly began the long and arduous work that was the creation of Brazil's new constitution. However, before even a single article was voted on, there was one thing that was crystal clear to all of the Assembly's participants, and that was the fact that, much to president Ulysses' despair, PMDB was on the verge of falling apart. Indeed, had the party's parliamentary wing gone entirely to one direction or another, either Maciel or Siveira would have scored an unquestionable, decisive victory. Instead, PMDB fractured itself right in the middle, and the Assembly would now be plagued by endless bickering between two sides with roughly equal power (2).

In June 25th, 1988, while the Constitution's articles were still being voted on, the inevitable happened: PMDB's progressive wing broke away from the main party, and founded a new group, the PSDB (Brazilian Social Democratic Party). Unlike most of its contemporaries, which started out small and later grew larger (such as PT and PTB), PSDB already had, right after its founding, forty one deputies, six senators and one state governor (Minas Gerais' Itamar Franco). With a toucan as its main symbol, it was created to be a center-left, moderate party, and its most important members were presitigious politicians like senators Mário Covas (who became PSDB's first president) and José Richa, deputies such as José Serra, Geraldo Alckmin, Ciro Gomes and Pimenta da Veiga, and other important figures such as former São Paulo governor Franco Montoro. Brazil would soon find out in that year's municipal elections if this new party's "natural bigness" (probably not a real word, sorry) really meant anything.

The founding members of PSDB.

Unfortunately, thanks to events largely outside their control, the tucanos ultimately failed to truly get the attention of the media, at least for now. The reality was that the creation of PSDB didn't really change the balance of power in the legislature or the Constituent Assembly, since they were already siding with the leftists in Congress to begin with. Plus, there were much juicier stories to report on, like the occasional fistfights that plagued the Assembly and the ever more frequent strikes that crippled the national economy and, in one tragic case that occurred in the industrial city of Volta Redonda (RJ), ended in a confrontation with the army that resulted in the death of three workers and around fifty more wounded (3). This event, combined with the recession which, while not as bad as it had been in 86 and 87, still refused to go away, and the utter collapse of PMDB in the municipal elections of November 15, made it so that the federal government reached the peak of its unpopularity. In a poll conducted by IBOPE that was released in December 1988, it was revealed that only 15% of the Brazilian population still had a favourable view of the administration headed by president Ulysses Silveira Guimarães (4).

Soldiers on a tank facing striking ironworkers in Volta Redonda before all hell broke loose.

Those stories were all from the domestic front, and there was no shortage of other interesting things happening around the globe. Argentina, Brazil's big southern neighbor, defeated a coup d'état attempt thanks to president Raúl Alfonsín's veto of the full stop law (Ley de Punto Final), which would've ended prosecutions against agents of the old military dictatorship that were not already in jail (5). In the north, the Perfect Dictatorship that ruled Mexico for 59 years finally collapsed, and in the United States, president Ronald Reagan resigned in disgrace thanks to a scandal whose was scale comparable to Watergate. In Asia, several dictators in the Far East were toppled by popular revolutions, and in the Middle East, Iraq ceased to exist as a functional state after its ruler, Saddam Hussein, was overthrown and executed after being soundly defeated by Iran, something that put all Arab nations in high alert (6).

...Wait a minute, we're yet to talk about the new Constitution. I must apologise, for I rushed things a bit. Anyway, back to Brasília!

Finally, after a year and a half of arguing, voting, one or two fistifights, and more arguing, the new Brazilian Constitution was fully elaborated and was unanimously promulgated by both houses of Congress in one final triumphant session. Lysâneas Maciel, who presided over the whole process, finished it with an emotional and truly memorable speech that was broadcasted to the entire country. He proudly declared the complete hatred and revulsion he felt towards any kind of dictatorship, especially the ones that plundered and butchered Latin America for so many years. At long last, he finished, Brazil, through its new national charter, was ready to cast that hideous spectre to the dustbin of history, and that the long night that started in 1964 finally came to an end. The standing ovation he received lasted at least five minutes, and after that, all lawmakers in the chamber held their hands together and sang the Brazilian National Anthem.

Here are some of the new Constitution's articles, in no particular order:

- People have the right to meet and congregate as they please, without the fear of government repression.

- The working class once again has the right to strike and create trade unions without outside interference.

- The nation's highest executive rank, the office of president, is to be elected by the people in a two round system.

- The presidential term, like all other executive offices, is set to last for four years, and the placeholder can run for a second term if he or she so wishes (7).

- An exception is to be made in the case of the incumbent president (Ulysses Guimarães) and his immediate successor, whose terms will last five years.

- All sovereign citizens with 18 years of age or older, including the illiterate, have the right to vote, and are, in fact, forced to pay a fine if they don't do their duty.

- The working week is to be set at 40 hours, with eight hours a day.

- Every citizen deserves free and decent healthcare. This leads to the creation of the SUS (Single Healthcare Service) a government funded universal healthcare system.

- The federal government has the authorisation to confiscate unproductive farmland from large landowners and distribute them to poor farmers. In other words, land reform, something that infuriated many latifundários and brought great joy many activists and the left, since it was something they desired to achieve for decades. This was, of all articles, the hardest to pass, and it only did so after a week of seemingly endless discussion (8).

The new supreme law was with no doubt the most democratic of all the constitutions that Brazil had. Thanks to that, and the context it was written in, it was given a most kind and deserving nickname: Constituição Cidadã, the Citizen's Constitution.

President Ulysses could not be happier. He couldn't care less about his and PMDB's unpopularity, that was irrelevant. What truly mattered was the fact that now, after 21 years of darkness, his beloved country was finally free to choose its own destiny. This was the best day of his life.

------------------

Notes:

(1) IOTL, Juruna ran for reelection in 1986, but was defeated. He then ran for a seat in the Chamber of Deputies in 1990 and 1994, losing both times. Finally, he died a depressed and forgotten man, a fate which he absolutely did not deserve.

(2) This is a very big difference. IOTL, the Constituent Assembly was almost completely dominated by the Centrão, thanks to the PMDB landslide of 1986.

(3) As OTL.

(4) Poor guy. Still, at least that's higher than José Sarney's 7%. After all, he didn't deceive his people with a shoddy economic plan, so there's that.

(5) I might be mistaken here, but I believe Alfonsín was initially opposed to this law IOTL, only later changing his opinion due to the possibility of a coup. Here, he decides that is a tolerable risk to ensure that all of the thugs who worked for the Proceso de Reorganinización Nacional go to prison. Naturally, such a course of action has its consequences.

(6) Spoiler alert! Spoiler alert!

(7) The president was originally forbidden from running for a second term IOTL. Didn't matter much, since president Fernando Henrique Cardoso bribed Congress into passing a reelection amendment.

(8) The federal government is supposed to do that IOTL, but only if said land doesn't "execute its social function" or something like that. This creates a loophole that ensures that this legislation impossible to enforce. Here, since there's an awful lot more leftists in the Constituent Assembly, that doesn't happen, to the ire of latifundiários like Kátia Abreu, Blairo Maggi and Ronaldo Caiado.

Last edited:

Fresh new update!

Feel free to report any typos or things that you may find implausible. As always, constructive criticism is much appreciated.

Feel free to report any typos or things that you may find implausible. As always, constructive criticism is much appreciated.

Regarding Chapter 9, I added a new threadmark and edited in an article of the new Constitution in regards to universal healthcare, which I thought was pretty important to add.

In the next few chapters, we'll deal with the mayoral elections that occurred in 1988. I can't say much about them, other than the fact that @ByzantineCaesar will probably love my next chapter.

In the next few chapters, we'll deal with the mayoral elections that occurred in 1988. I can't say much about them, other than the fact that @ByzantineCaesar will probably love my next chapter.

Part 10: 1988 Elections, Part One

@ByzantineCaesar, this one's for you. Well, mostly for me, I guess, but also for you  .

.

Also, you called it! Meus Parabéns!

------------------

Part 10: 1988 Elections, Part One

The Constituent Assembly wasn't the only big thing to happen in 1988. In that same year, the people of Brazil were once again going to elect new mayors to administrate their municipalities. Since this was only the second time that those who lived in the state capitals (and other "National Security Areas", such as Volta Redonda and Santos) elected their own mayors, there was still a strange air of uneasy anticipation around, a remnant of the euphoric atmosphere that came with this newly found freedom that didn't die down just yet. The fact that the presidential elections were literally right around the corner only raised the stakes involved, which certainly didn't help cool the situation down. One thing that everyone was sure of was that there would be no uniform sweep of the country by one single party, the only question being who was going to get the biggest slice of the cake.

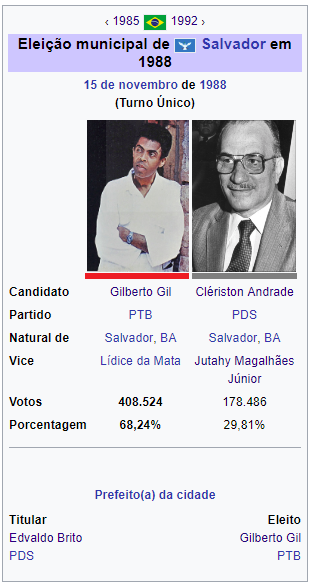

Salvador, capital of the state of Bahia, was one of the biggest "hot zones", so to say.

To understand the city's politics, one must take a look at Bahia's politics as a whole. The state was run for almost two decades by a right-wing political machine led by the infamous coronel (oligarch) Antônio Carlos Magalhães, best known by his initials ACM. His unwavering support of the dictatorship rewarded him first with an appointment by the federal government to the mayoralty of Salvador in 1967 and finally the state governorship in 1970, which he used to turn the state into his personal fiefdom. His autocratic behavior and leadership earned him the well deserved nickname of Imperador (The Emperor).

Needless to say, Salvador, a hotbed of opposition against the military government, despised him, and voted en masse against his PDS allies.

ACM and president Figueiredo at a PDS campaign event in 1982.

ACM and president Figueiredo at a PDS campaign event in 1982.

And here's where things get weird. You see, in 1982, 62% of Salvador's voters voted for Roberto Santos, the PMDB candidate for governor, and, therefore, ACM's enemy. Four years later, they did the same thing, except they broke in favour of the victorious campaign led Waldir Pires, a former peemedebista who became a member of PTB and one of Leonel Brizola's most important allies in the Northeast. However, just a year earlier, in 1985, while PMDB was still in its honeymoon period and swept most of the country, the Salvador mayoral was won, against all possible odds, by former appointed mayor Edvaldo Brito, who was one of ACM's closest allies. Despite numerous (and credible) claims of fraud, the result stood, and Brito became mayor in January 1, 1986 (1).

His administration was a disaster. Seen by much of the city's population as illegitimate, which greatly hurt his popularity, his ability to govern was further hampered by the fact that the City Council was controlled by an opposition supermajority. His situation became even worse after the 1986 election, in which the already mentioned Waldir Pires became governor, completely isolating the mayor from any outside help. Besieged by an apathetic federal government, a governor who straight up questioned his very legitimacy and a hostile City Council, Edvaldo Brito spent his three year term as a lame duck.

Mayor Edvaldo Brito in one of Salvador's poorer neighborhoods.

Mayor Edvaldo Brito in one of Salvador's poorer neighborhoods.

When 1988 came in, the opposition was dead set on not losing the valuable mayoralty thanks to some "miracle" again. As such, they all unified behind a single candidate, someone who was already in politics for a few years, but not too long, and whose name was easily recongizable.

That candidate was none other than the famous artist and longtime political activist Gilberto Gil. This choice really wan't as outlandish as an outside might have believed, considering that Gil was already a congressman, and helped write the Citizen's Constitution. Not only that, but he was elected in 1986 with a resounding 145.000 votes, becoming Bahia's most voted deputy. Governor Waldir peronally admitted in an interview many years later that he would rather have supported Virgildásio de Senna, another deputy and Salvador's last mayor before the dictatorship, but supported the newcomer after Senna declared that he wasn't interested in the mayoralty (2). PDS's anemic, half-dead response to Gil's candidacy was Clériston Andrade, who was Waldir's predecessor as governor and an appointed ("bionic") mayor during the seventies. The same man who got crushed in this very city just six years ago.

The result surprised no one. Well, at least no one who wasn't an outsider. Many newspapers and TV channels, even a few foreign ones, were shocked and eagerly reported the result, speculating what would be the future for the new mayor of Salvador. He would go very far indeed.

------------------

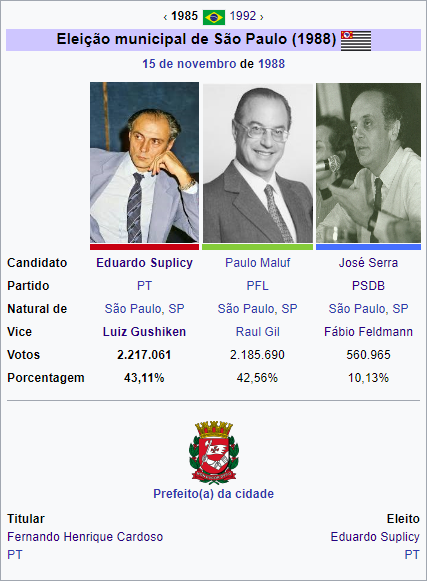

No matter what happened anywhere else, São Paulo was always going to be in the center of the media's attention. Who could blame them? After all, the city had a population which was bigger than that of many countries, and was by far the biggest prize available for the night. Naturally, Brazil's largest city was obviously going to have the toughest and most expensive mayoral race of them all.

More than just an ordinary election, the race also symbolised the ongoing struggle between incumbent center-left mayor Fernando Henrique Cardoso and right wing governor Silvio Santos, two very popular and powerful figures in São Paulo politics. The former was seen a restless defender of democracy and a hardworking and honest administrator, while the latter was a maverick and equally restless anti corruption campaigner. Both of them had very big plans for the not so distant future, and since one's success almost always depends on his rival's failure, their administration clashed several times, polarising the city's politics.

Two very ambitious men.

Two very ambitious men.

The first contender to announce his candidacy was none other than Paulo Maluf himself. He immediatly won Santos' endorsement, no doubt a reward for supporting him in the gubernatorial election two years ago, and immediatly became the frontrunner. Not only that, but he formed a coalition which included his own party (PFL), PDS and PDC, which not only gave his campaign a lot of free airtime and money, but also united the right behind him and further solidified his position. Naturally, the left was thrown into a state of panic by these developments, but they were divided into multiple parties that often bickered among themselves. Still, the threat of Maluf winning the mayoralty turned the idea of a broad front into a possibility.

At the same time, Fernando Henrique absolutely not just going to let that corrupt spawn of the dictatorship just plunder the city' finances and ruin everything he achieved, something that would endanger his own political future. As such, he began to manouver himself into a position from which he could make this progressive coalition a reality. His first move, his defection from PMDB, was somehow both very predictable and surprising at the same time. Everyone knew that he was going to leave his old party eventually, since many of his fellow mayors did it (it was a sinking ship, after all), but what truly stunned everyone was his decision to join the Workers' Party. After that was done, he made sure everyone knew that his preferred candidate was deputy mayor Eduardo Suplicy.

In retrospect, this decision really shouldn't have been so shocking, considering that FHC had longstanding friendly relations with several important petistas, including Lula himself, and were an important part of his administration (3). Still, his decison to "cheat" on his former progressive PMDB colleagues by joining PT instead of participating on the creation of PSDB left them quite miffed, and the new party launched former governor Franco Montoro, who was still quite popular despite the Michel Temer scandal, as its mayoral candidate. However, Montoro, a man who was already in his seventies, quickly fell ill and was replaced by his running mate, federal deputy José Serra.

Fernando Henrique made one last attempt to convince PSDB to join Suplicy's "grand coalition", which included all major left-wing parties, ranging from small groups such as the two communist parties, medium ones like PSB and finally the mighty PTB. Unfortunately, the tucanos were still angry at the mayor's "betrayal", and Serra maintained his candidacy.

Maluf's opposition was divided.

Nailbiter? Nailbiter. It is very difficult to describe just how close the election was, and Maluf, who led the polls during the entire campaign, was defeated in what became the single closest election in the history of São Paulo. It is even more difficult to put into words just how elated FHC and his fellow leftists were at the result. In the end, what truly decided the election was a last minute defection of people who at first intended to vote for Serra but switched to Suplicy in election day, in order to keep PFL candidate, who they saw as the worst possible option by far, from once again ruling the largest city in Brazil (4). Maluf didn't know it yet, but this would prove to be the high water mark of his democratic career.

Meanwhile, all Fernando Henrique, Suplicy and their fellow petistas thought about was just how many ways they could celebrate their great victory. They certainly had a very good reason to do that.

------------------

Notes:

(1) IOTL, Brito lost by a massive margin to another former mayor, PMDB's Mário Kertész. Here, he somehow squeaks in, shocking everyone, including himself. Since he trailed behind his opponent by a large margin throughout the entire race, and PDS did try to steal a bunch of state elections in 1982, his opponents have a reason to be skeptical.

(2) IOTL, Gil (who never ran for office before) tried to run for mayor as the PMDB candidate, but his name was vetoed by governor Waldir Pires, so he ran for and won a seat in the City Council. Here, since Gil has been a politician for a (very) short while, Pires isn't as skeptical.

(3) IOTL, Fernando Henrique had friendly relations with Lula for many years, and these relation only truly broke down on 1994, when they both ran for president on opposing parties. Here, since PT has proven itself to be a reliable ally during his administration, they are even closer politically.

(4) It didn't help that Serra has the appearance and charisma of a zombie. Seriously.

Also, you called it! Meus Parabéns!

------------------

Part 10: 1988 Elections, Part One

The Constituent Assembly wasn't the only big thing to happen in 1988. In that same year, the people of Brazil were once again going to elect new mayors to administrate their municipalities. Since this was only the second time that those who lived in the state capitals (and other "National Security Areas", such as Volta Redonda and Santos) elected their own mayors, there was still a strange air of uneasy anticipation around, a remnant of the euphoric atmosphere that came with this newly found freedom that didn't die down just yet. The fact that the presidential elections were literally right around the corner only raised the stakes involved, which certainly didn't help cool the situation down. One thing that everyone was sure of was that there would be no uniform sweep of the country by one single party, the only question being who was going to get the biggest slice of the cake.

Salvador, capital of the state of Bahia, was one of the biggest "hot zones", so to say.

To understand the city's politics, one must take a look at Bahia's politics as a whole. The state was run for almost two decades by a right-wing political machine led by the infamous coronel (oligarch) Antônio Carlos Magalhães, best known by his initials ACM. His unwavering support of the dictatorship rewarded him first with an appointment by the federal government to the mayoralty of Salvador in 1967 and finally the state governorship in 1970, which he used to turn the state into his personal fiefdom. His autocratic behavior and leadership earned him the well deserved nickname of Imperador (The Emperor).

Needless to say, Salvador, a hotbed of opposition against the military government, despised him, and voted en masse against his PDS allies.

And here's where things get weird. You see, in 1982, 62% of Salvador's voters voted for Roberto Santos, the PMDB candidate for governor, and, therefore, ACM's enemy. Four years later, they did the same thing, except they broke in favour of the victorious campaign led Waldir Pires, a former peemedebista who became a member of PTB and one of Leonel Brizola's most important allies in the Northeast. However, just a year earlier, in 1985, while PMDB was still in its honeymoon period and swept most of the country, the Salvador mayoral was won, against all possible odds, by former appointed mayor Edvaldo Brito, who was one of ACM's closest allies. Despite numerous (and credible) claims of fraud, the result stood, and Brito became mayor in January 1, 1986 (1).

His administration was a disaster. Seen by much of the city's population as illegitimate, which greatly hurt his popularity, his ability to govern was further hampered by the fact that the City Council was controlled by an opposition supermajority. His situation became even worse after the 1986 election, in which the already mentioned Waldir Pires became governor, completely isolating the mayor from any outside help. Besieged by an apathetic federal government, a governor who straight up questioned his very legitimacy and a hostile City Council, Edvaldo Brito spent his three year term as a lame duck.

When 1988 came in, the opposition was dead set on not losing the valuable mayoralty thanks to some "miracle" again. As such, they all unified behind a single candidate, someone who was already in politics for a few years, but not too long, and whose name was easily recongizable.

That candidate was none other than the famous artist and longtime political activist Gilberto Gil. This choice really wan't as outlandish as an outside might have believed, considering that Gil was already a congressman, and helped write the Citizen's Constitution. Not only that, but he was elected in 1986 with a resounding 145.000 votes, becoming Bahia's most voted deputy. Governor Waldir peronally admitted in an interview many years later that he would rather have supported Virgildásio de Senna, another deputy and Salvador's last mayor before the dictatorship, but supported the newcomer after Senna declared that he wasn't interested in the mayoralty (2). PDS's anemic, half-dead response to Gil's candidacy was Clériston Andrade, who was Waldir's predecessor as governor and an appointed ("bionic") mayor during the seventies. The same man who got crushed in this very city just six years ago.

The result surprised no one. Well, at least no one who wasn't an outsider. Many newspapers and TV channels, even a few foreign ones, were shocked and eagerly reported the result, speculating what would be the future for the new mayor of Salvador. He would go very far indeed.

------------------

No matter what happened anywhere else, São Paulo was always going to be in the center of the media's attention. Who could blame them? After all, the city had a population which was bigger than that of many countries, and was by far the biggest prize available for the night. Naturally, Brazil's largest city was obviously going to have the toughest and most expensive mayoral race of them all.

More than just an ordinary election, the race also symbolised the ongoing struggle between incumbent center-left mayor Fernando Henrique Cardoso and right wing governor Silvio Santos, two very popular and powerful figures in São Paulo politics. The former was seen a restless defender of democracy and a hardworking and honest administrator, while the latter was a maverick and equally restless anti corruption campaigner. Both of them had very big plans for the not so distant future, and since one's success almost always depends on his rival's failure, their administration clashed several times, polarising the city's politics.

The first contender to announce his candidacy was none other than Paulo Maluf himself. He immediatly won Santos' endorsement, no doubt a reward for supporting him in the gubernatorial election two years ago, and immediatly became the frontrunner. Not only that, but he formed a coalition which included his own party (PFL), PDS and PDC, which not only gave his campaign a lot of free airtime and money, but also united the right behind him and further solidified his position. Naturally, the left was thrown into a state of panic by these developments, but they were divided into multiple parties that often bickered among themselves. Still, the threat of Maluf winning the mayoralty turned the idea of a broad front into a possibility.

At the same time, Fernando Henrique absolutely not just going to let that corrupt spawn of the dictatorship just plunder the city' finances and ruin everything he achieved, something that would endanger his own political future. As such, he began to manouver himself into a position from which he could make this progressive coalition a reality. His first move, his defection from PMDB, was somehow both very predictable and surprising at the same time. Everyone knew that he was going to leave his old party eventually, since many of his fellow mayors did it (it was a sinking ship, after all), but what truly stunned everyone was his decision to join the Workers' Party. After that was done, he made sure everyone knew that his preferred candidate was deputy mayor Eduardo Suplicy.

In retrospect, this decision really shouldn't have been so shocking, considering that FHC had longstanding friendly relations with several important petistas, including Lula himself, and were an important part of his administration (3). Still, his decison to "cheat" on his former progressive PMDB colleagues by joining PT instead of participating on the creation of PSDB left them quite miffed, and the new party launched former governor Franco Montoro, who was still quite popular despite the Michel Temer scandal, as its mayoral candidate. However, Montoro, a man who was already in his seventies, quickly fell ill and was replaced by his running mate, federal deputy José Serra.

Fernando Henrique made one last attempt to convince PSDB to join Suplicy's "grand coalition", which included all major left-wing parties, ranging from small groups such as the two communist parties, medium ones like PSB and finally the mighty PTB. Unfortunately, the tucanos were still angry at the mayor's "betrayal", and Serra maintained his candidacy.

Maluf's opposition was divided.

Nailbiter? Nailbiter. It is very difficult to describe just how close the election was, and Maluf, who led the polls during the entire campaign, was defeated in what became the single closest election in the history of São Paulo. It is even more difficult to put into words just how elated FHC and his fellow leftists were at the result. In the end, what truly decided the election was a last minute defection of people who at first intended to vote for Serra but switched to Suplicy in election day, in order to keep PFL candidate, who they saw as the worst possible option by far, from once again ruling the largest city in Brazil (4). Maluf didn't know it yet, but this would prove to be the high water mark of his democratic career.

Meanwhile, all Fernando Henrique, Suplicy and their fellow petistas thought about was just how many ways they could celebrate their great victory. They certainly had a very good reason to do that.

------------------

Notes:

(1) IOTL, Brito lost by a massive margin to another former mayor, PMDB's Mário Kertész. Here, he somehow squeaks in, shocking everyone, including himself. Since he trailed behind his opponent by a large margin throughout the entire race, and PDS did try to steal a bunch of state elections in 1982, his opponents have a reason to be skeptical.

(2) IOTL, Gil (who never ran for office before) tried to run for mayor as the PMDB candidate, but his name was vetoed by governor Waldir Pires, so he ran for and won a seat in the City Council. Here, since Gil has been a politician for a (very) short while, Pires isn't as skeptical.

(3) IOTL, Fernando Henrique had friendly relations with Lula for many years, and these relation only truly broke down on 1994, when they both ran for president on opposing parties. Here, since PT has proven itself to be a reliable ally during his administration, they are even closer politically.

(4) It didn't help that Serra has the appearance and charisma of a zombie. Seriously.

Last edited:

Here's an image to celebrate this TL's newest update.

As always, comments and constructive criticism are much appreciated.

As always, comments and constructive criticism are much appreciated.

Gilberto Gil giving an interview shortly after his inauguration as mayor of Salvador.

Last edited:

Share: