20. The end of the Great War.

At Compiègne, Matthias Erzberger, who had Count Alfred von Oberndorff of the Foreign Ministry by his side, was received by the French Chief of Staff, General Ferdinand Foch, Admiral Rosslyn Wemyss representing Britain and Colonel Charles Kilborne, for the United States. Having read out the terms, Foch made a number of token concessions when Erzberger begged for modifications. However, as he was under heavy pressure from Ebert to conclude an armistice with all haste, was ready to sign the document. At 7:38pm, the German delegation added their signatures to the armistice and Foch dismissed them. The terms would come into effect at 5am the next morning, March 16, 1918.

In France and Belgium, the Allied forces rejoiced at the end of hostilities. However, in contrast to the happines that ran thorugh the trenches, Haig kept true to himself and in the followig morning he met his army commanders and discussed with them the plans for an advance to the German frontier in preparation for the occupation of the Rhine bridgeheads. Meanwhile, American, French and British troops fraternised with locals, dining on food and drink offered by the grateful Belgian and French villagers. Soldiers sung and danced as bonfires were lit up and down the line. As many officers and men indulged in revelry together, the emotions were mixed. A lieutenant in the Coldstream Guards, Alex Wilkinson, wrote in his diary ‘The jolly old war has come to an end at last, and a good end too.’ Acting brigadier general Adrian Carton de Wiart simply stated "Frankly, I had enjoyed the war." Captain Edmund Blackadder recounted how he ‘went round the trenches and told the news to the NCOs and men. As an example of the calmness with which it was received, when I met Corporal S. Baldrick walking across the support trench and told him the news, he merely halted, saluted, said “very good, sir” and walked on to take care of his turnips.’

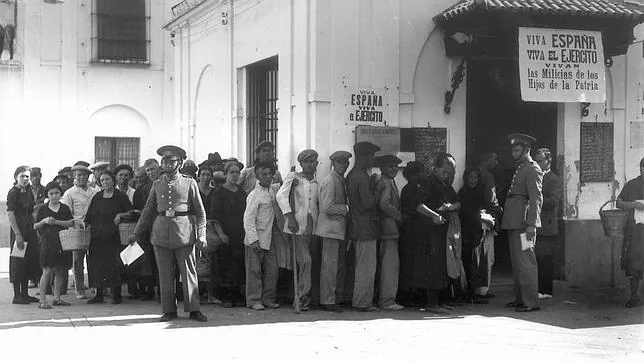

Meanwhile, in Spain, the monarchist propaganda had achieved an unexpected sucess. Suddenly, the idea of return of the Borbon family to the Spanish throne with Prince Alfonso became quite appealing for not only for the Spanish monarchists, but also to those who hoped for a deep reform of the state. This attitude was reinforced when Alfonso, from his golden exile in Britain, made public his Manifiesto de Sandhurst (Sandhurst Manifesto), where he set the ideological basis of the Bourbon Restoration and proclaimed himself the sole representative of the Spanish monarchy.

In France and Belgium, the Allied forces rejoiced at the end of hostilities. However, in contrast to the happines that ran thorugh the trenches, Haig kept true to himself and in the followig morning he met his army commanders and discussed with them the plans for an advance to the German frontier in preparation for the occupation of the Rhine bridgeheads. Meanwhile, American, French and British troops fraternised with locals, dining on food and drink offered by the grateful Belgian and French villagers. Soldiers sung and danced as bonfires were lit up and down the line. As many officers and men indulged in revelry together, the emotions were mixed. A lieutenant in the Coldstream Guards, Alex Wilkinson, wrote in his diary ‘The jolly old war has come to an end at last, and a good end too.’ Acting brigadier general Adrian Carton de Wiart simply stated "Frankly, I had enjoyed the war." Captain Edmund Blackadder recounted how he ‘went round the trenches and told the news to the NCOs and men. As an example of the calmness with which it was received, when I met Corporal S. Baldrick walking across the support trench and told him the news, he merely halted, saluted, said “very good, sir” and walked on to take care of his turnips.’

Meanwhile, in Spain, the monarchist propaganda had achieved an unexpected sucess. Suddenly, the idea of return of the Borbon family to the Spanish throne with Prince Alfonso became quite appealing for not only for the Spanish monarchists, but also to those who hoped for a deep reform of the state. This attitude was reinforced when Alfonso, from his golden exile in Britain, made public his Manifiesto de Sandhurst (Sandhurst Manifesto), where he set the ideological basis of the Bourbon Restoration and proclaimed himself the sole representative of the Spanish monarchy.

Last edited: