You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alternate Electoral Maps

- Thread starter Tayya

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

And what would that be?

That while Oregon isn't that Democratic, it has a lot of liberals.

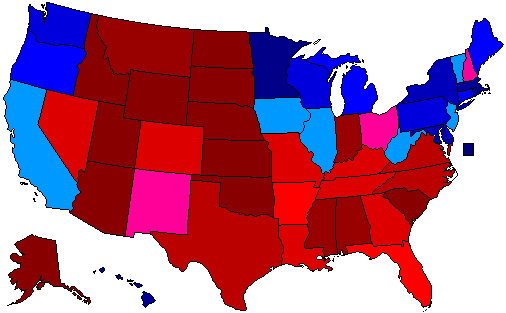

After seeing a thread on a Tilden Presidency, I had a thought about adjusting the Republican vote in the South as though there was no intimidation and threats going on; see what the eleciton would look like if the Democrats played as fair as they did in 1872. So, I took the aggregate change in number of voters outside of the Confederacy, then applied that number to the Republican vote total in each Confederate states. In some cases, the new total was less than than the OTL Republican vote, so I used that number.

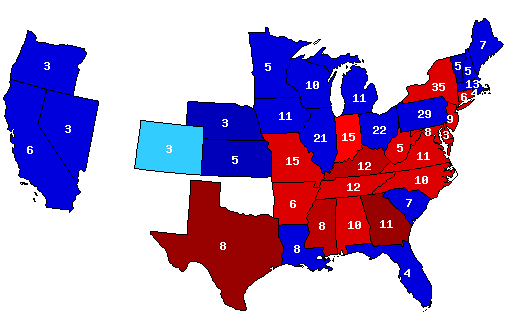

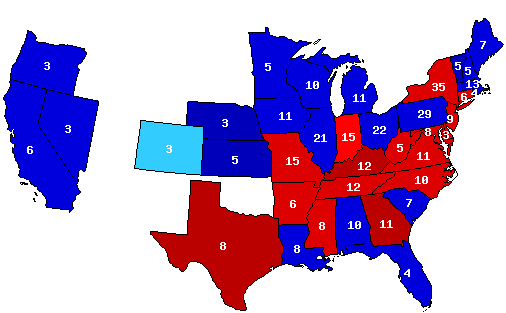

OTL 1876.

Hayes/Wheeler - 47.92% - 185 EVs

Tilden/Hendricks - 50.92% - 184 EVs

Democrats Play Fair 1876

Hayes/Wheeler - 48.85% - 195 EVs

Tilden/Hendricks - 50.01% - 174 EVs

While the Democratic percentage goes down throughout the South, the real difference is that the republicans take Alabama by about 2,000 votes, which makes the electoral commission necessary.

OTL 1876.

Hayes/Wheeler - 47.92% - 185 EVs

Tilden/Hendricks - 50.92% - 184 EVs

Democrats Play Fair 1876

Hayes/Wheeler - 48.85% - 195 EVs

Tilden/Hendricks - 50.01% - 174 EVs

While the Democratic percentage goes down throughout the South, the real difference is that the republicans take Alabama by about 2,000 votes, which makes the electoral commission necessary.

<SNIP>

The only problem with this kind of analysis however is that inevitably has its flaws, as Mississippi shows; over half the population was African-American and Grant carried it in '72 by a ten percent larger margin than Alabama, but it is Alabama which moves over first, and barely so, under the rules as you have established. To be fair though, I'm not certain if it is really possible to get an "accurate" picture of a fair contest. :/

The only problem with this kind of analysis however is that inevitably has its flaws, as Mississippi shows; over half the population was African-American and Grant carried it in '72 by a ten percent larger margin than Alabama, but it is Alabama which moves over first, and barely so, under the rules as you have established. To be fair though, I'm not certain if it is really possible to get an "accurate" picture of a fair contest. :/

True, though I did what I could for a very rough glance. Republicans were just working at a disadvantage anyway due to the national mood that brought out the Democratic turnout. In Missipppi and Arkansas, Republican turnout doubles when compared to OTL turnout. Mississippi goes 54-46 (instead of 68-32) for Tilden and Arkansas goes 55-45 (instead of 60-50) for Tilden. South Carolina and Florida I left as OTL, while the rest saw some modest bumps in Republican support. Of the ones that changes, North Carolina changed the least.

/Edit

Oh, and a point I kind of had in mind was that there seems to be some dispute over who was trying to "steal" this election and there's kind of an assumption that Tilden couldn't win without the suppression of the African American vote. Which, while true, it does look Tilden almost certainly was going to win the national popular vote no matter what happens and that 1876 will have to be one of those elections where many people are happy about the "undemocratic" result happening. 1824 is that election for me personally.

True, though I did what I could for a very rough glance. Republicans were just working at a disadvantage anyway due to the national mood that brought out the Democratic turnout. In Missipppi and Arkansas, Republican turnout doubles when compared to OTL turnout. Mississippi goes 54-46 (instead of 68-32) for Tilden and Arkansas goes 55-45 (instead of 60-50) for Tilden. South Carolina and Florida I left as OTL, while the rest saw some modest bumps in Republican support. Of the ones that changes, North Carolina changed the least.

/Edit

Oh, and a point I kind of had in mind was that there seems to be some dispute over who was trying to "steal" this election and there's kind of an assumption that Tilden couldn't win without the suppression of the African American vote. Which, while true, it does look Tilden almost certainly was going to win the national popular vote no matter what happens and that 1876 will have to be one of those elections where many people are happy about the "undemocratic" result happening. 1824 is that election for me personally.

And now, to completely undercut my point from before. Here is what the map looks like if the Democrats "play fair" but the Republicans don't, suppressing Democratic votes in the South in the same fashion as they did in 1872.

Hayes/Wheeler - 49.56% - 199 EVs

Tilden/Hendricks - 49.00% - 170 EVs

Democrats get half as many voters in South Carolina as in OTL, which would be enough to put Tilden over the top in the state and in the national popular vote.

I don't think you can accurately describe what the Republican controlled states did in 1872 as 'voter suppression,' given that the voters in question were traitors who backed the Confederacy. What of course would be unfair is allowing the former Slave Power to return to power by allowing it to openly organize, which is exactly what the GOP did after 1874.

I don't think you can accurately describe what the Republican controlled states did in 1872 as 'voter suppression,' given that the voters in question were traitors who backed the Confederacy. What of course would be unfair is allowing the former Slave Power to return to power by allowing it to openly organize, which is exactly what the GOP did after 1874.

Just because the reasons weren't arguably valid, I would still say it meets the textbook definition of voter suppression. I wasn't really trying to get into a political debate, I just wanted to approach a notorious election from a couple of angles and see what shakes out. As someone who doesn't like the electoral college, and purely from a fan of democratic elections, it looks to me like Samuel Tilden should have been President then and there...everything else put aside.

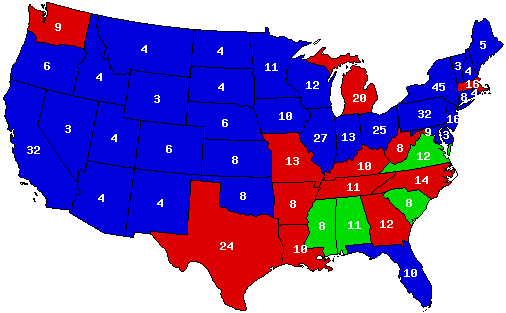

The Curveball: Part I

When Adlai Stevenson secured the nomination at the 1956 Democratic National Convention for the second time in as many elections, most expected that he would select John Sparkman once again as his running mate. However, through a combination of ambivalence on Sparkman's part and a desire to freshen up the Democratic ticket, Stevenson shocked the gathered delegates when he announced that he would be selecting a new running mate. With only twenty four hours before the balloting, a number of candidates scrambled to secure the open position.

Amongst them was Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, who at thirty nine was by far the youngest man in the running. The main opposition came in the form of Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, a liberal Democrat with strong ties to the New Deal coalition and Stevenson himself.

With Stevenson remaining aloof from the process though, Kefauver was forced to fight Kennedy largely unassisted. Despite this, it surprised many when the young New Englander prevailed on the third ballot, earning a spot on that year's ticket.

As the dust settled and the reactions to the surprising and exciting victory began to pour in, the Stevenson campaign would learn two things, the first being that Kennedy's presence had fired a lot of people up, the second being that a lot of those people were incredibly unhappy with Kennedy's Catholicism.

While Kennedy, to his credit, was skillful in defusing many of the religious tensions that surrounded his vice presidential candidacy, it has generally been agreed upon by historians that his presence on the ticket was more of a detriment to the Stevenson campaign than an attribute. His health problems were skillfully used by the Eisenhower campaign to deflect attention away from the President's own heart problems, and his adultery, while not particularly scandalous by '50s standards, was still enough to attract controversy.

Overall, with the Korean War ended and the nation enjoying unprecedented post-war prosperity, the election never slipped out of President Eisenhower's control, and the curveball that was John F. Kennedy was unsuccessful in returning the Democratic party to the White House.

President Dwight Eisenhower/Vice President Richard Nixon - 470 EV

Former Governor Adlai Stevenson/Senator John Kennedy - 61 EV

When Adlai Stevenson secured the nomination at the 1956 Democratic National Convention for the second time in as many elections, most expected that he would select John Sparkman once again as his running mate. However, through a combination of ambivalence on Sparkman's part and a desire to freshen up the Democratic ticket, Stevenson shocked the gathered delegates when he announced that he would be selecting a new running mate. With only twenty four hours before the balloting, a number of candidates scrambled to secure the open position.

Amongst them was Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, who at thirty nine was by far the youngest man in the running. The main opposition came in the form of Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, a liberal Democrat with strong ties to the New Deal coalition and Stevenson himself.

With Stevenson remaining aloof from the process though, Kefauver was forced to fight Kennedy largely unassisted. Despite this, it surprised many when the young New Englander prevailed on the third ballot, earning a spot on that year's ticket.

As the dust settled and the reactions to the surprising and exciting victory began to pour in, the Stevenson campaign would learn two things, the first being that Kennedy's presence had fired a lot of people up, the second being that a lot of those people were incredibly unhappy with Kennedy's Catholicism.

While Kennedy, to his credit, was skillful in defusing many of the religious tensions that surrounded his vice presidential candidacy, it has generally been agreed upon by historians that his presence on the ticket was more of a detriment to the Stevenson campaign than an attribute. His health problems were skillfully used by the Eisenhower campaign to deflect attention away from the President's own heart problems, and his adultery, while not particularly scandalous by '50s standards, was still enough to attract controversy.

Overall, with the Korean War ended and the nation enjoying unprecedented post-war prosperity, the election never slipped out of President Eisenhower's control, and the curveball that was John F. Kennedy was unsuccessful in returning the Democratic party to the White House.

President Dwight Eisenhower/Vice President Richard Nixon - 470 EV

Former Governor Adlai Stevenson/Senator John Kennedy - 61 EV

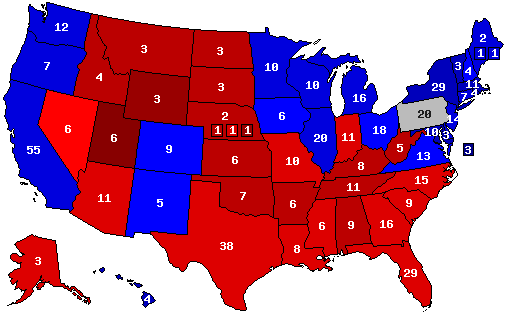

And a 2008-based "basemap":

Democrats - 278 EVs, 49.29%

Republicans - 260 EVs, 49.29%

Margin of victory <5:

Virginia: 1.02%

Colorado: 1.63%

Iowa: 2.21%

New Hampshire: 2.29%

Ohio: 2.73%

Minnesota: 2.92%

Pennsylvania: 3.00%

Maine, 2nd: 3.93%

Florida: 4.50%

Margin of victory <10:

Nevada: 5.17%

Nebraska, 2nd: 6.11%

Indiana: 6.29%

Wisconsin: 6.58%

North Carolina: 6.99%

Missouri: 7.45%

New Mexico: 7.81%

New Jersey: 8.25%

Oregon: 9.03%

Michigan: 9.15%

Montana: 9.58%

Washington: 9.86%

Maine: 10.00%

Democrats - 278 EVs, 49.29%

Republicans - 260 EVs, 49.29%

Margin of victory <5:

Virginia: 1.02%

Colorado: 1.63%

Iowa: 2.21%

New Hampshire: 2.29%

Ohio: 2.73%

Minnesota: 2.92%

Pennsylvania: 3.00%

Maine, 2nd: 3.93%

Florida: 4.50%

Margin of victory <10:

Nevada: 5.17%

Nebraska, 2nd: 6.11%

Indiana: 6.29%

Wisconsin: 6.58%

North Carolina: 6.99%

Missouri: 7.45%

New Mexico: 7.81%

New Jersey: 8.25%

Oregon: 9.03%

Michigan: 9.15%

Montana: 9.58%

Washington: 9.86%

Maine: 10.00%

Last edited:

Here's a map of how often each state voted for a party in the last 13 elections and the average votes for both sides (EVs from 2012):

Republican: 285 EVs, 46,477,087 PV (50.3%)

Democratic: 253 EVs, 45,924,936 PV (49.7%)

Alabama: 11-1-1

Alaska: 12-1

Arizona: 12-1

Arkansas: 8-4-1

California: 7-6

Colorado: 9-4

Connecticut: 8-5

Delaware: 8-5

DC: 13-0

Florida: 8-5

Georgia: 9-3-1

Hawaii: 11-2

Idaho: 12-1

Illinois: 7-6

Indiana: 11-2

Iowa: 7-6

Kansas: 12-1

Kentucky: 9-4

Louisiana: 9-3-1

Maine: 8-5

Maryland: 10-3

Massachusetts: 11-2

Michigan: 8-5

Minnesota: 12-1

Mississippi: 11-1-1

Missouri: 9-5

Montana: 11-2

Nebraska: 12-1

Nevada: 9-4

New Hampshire: 7-6

New Jersey: 7-6

New Mexico: 7-6

New York: 10-3

North Carolina: 10-3

North Dakota: 12-1

Ohio: 7-6

Oklahoma: 12-1

Oregon: 8-5

Pennsylvania: 9-4

Rhode Island: 11-2

South Carolina: 12-1

South Dakota: 12-1

Tennessee: 9-4

Texas: 10-3

Utah: 12-1

Vermont: 7-6

Virginia: 10-3

Washington: 9-5

West Virginia: 7-6

Wisconsin: 9-4

Wyoming: 12-1

Republican: 285 EVs, 46,477,087 PV (50.3%)

Democratic: 253 EVs, 45,924,936 PV (49.7%)

Alabama: 11-1-1

Alaska: 12-1

Arizona: 12-1

Arkansas: 8-4-1

California: 7-6

Colorado: 9-4

Connecticut: 8-5

Delaware: 8-5

DC: 13-0

Florida: 8-5

Georgia: 9-3-1

Hawaii: 11-2

Idaho: 12-1

Illinois: 7-6

Indiana: 11-2

Iowa: 7-6

Kansas: 12-1

Kentucky: 9-4

Louisiana: 9-3-1

Maine: 8-5

Maryland: 10-3

Massachusetts: 11-2

Michigan: 8-5

Minnesota: 12-1

Mississippi: 11-1-1

Missouri: 9-5

Montana: 11-2

Nebraska: 12-1

Nevada: 9-4

New Hampshire: 7-6

New Jersey: 7-6

New Mexico: 7-6

New York: 10-3

North Carolina: 10-3

North Dakota: 12-1

Ohio: 7-6

Oklahoma: 12-1

Oregon: 8-5

Pennsylvania: 9-4

Rhode Island: 11-2

South Carolina: 12-1

South Dakota: 12-1

Tennessee: 9-4

Texas: 10-3

Utah: 12-1

Vermont: 7-6

Virginia: 10-3

Washington: 9-5

West Virginia: 7-6

Wisconsin: 9-4

Wyoming: 12-1

Last edited:

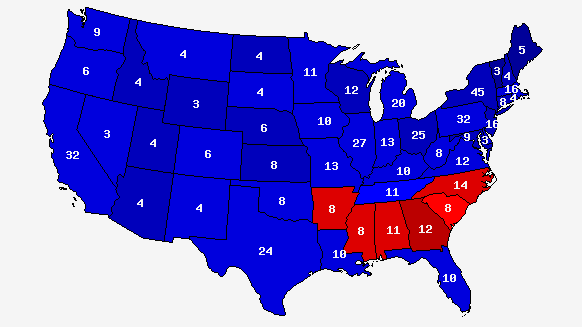

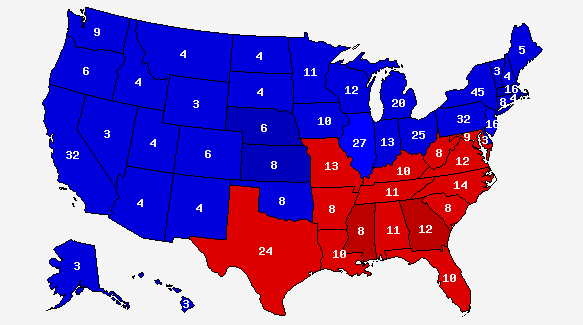

Due to President Truman's unpopularity, an economic recession, and the Chinese invasion of Korea in 1949, Truman would lose his re-election campaign in 1952.

United States Presidential Election, 1952

President Harry Truman/ Vice President Alben W. Barkley (Democratic) -155 EV

Senator Joseph McCarthy/ Senator Richard Nixon (Republican) - 337 EV

Senator Strom Thurmond/ Senator Harry Byrd (State's Rights) - 39 EV

United States Presidential Election, 1952

President Harry Truman/ Vice President Alben W. Barkley (Democratic) -155 EV

Senator Joseph McCarthy/ Senator Richard Nixon (Republican) - 337 EV

Senator Strom Thurmond/ Senator Harry Byrd (State's Rights) - 39 EV

He's using the normal colors used everywhere else but Atlas Forums.Um... You have the colours switched around.

He's using the normal colors used everywhere else but Atlas Forums.

I think she means the colour scheme is different in the text (which uses the regular colours) and the map (which uses Dave Leip's colours).

No, she means that the map colors don't match up with the colors in the post (post uses red for Republicans and blue for Democrats, but the map uses blue for Republicans and red for Democrats).He's using the normal colors used everywhere else but Atlas Forums.

The Curveball: Part 2

Eisenhower's second term got off to a smooth start with the approval of the 'Eisenhower Doctrine' for regards to diplomacy in the Middle East, and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, which was passed by congress despite a record twenty five hour filibuster by Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina.

However, unforeseen events would soon put a damper on the popular President's administration. The first of these was the launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union, which would prompt Eisenhower to advocate for a civilian space flight agency to be created. The second was a minor recession, which would last for much of the remainder of his presidency. The third was the downing of a U2 observation plane over the Soviet Union. The only silver lining of what became a serious international scandal was that the pilot, a certain Gary Powers, was killed during the destruction of his aircraft. Despite these incidents, Eisenhower remained popular and there were rumblings of support for a repeal of the 22nd Amendment as the 1960 election approached.

These never became more than theoretical however, and it is unlikely that a repeal effort would have passed even if Eisenhower had offered the attempt his public support. Besides, Eisenhower was nearly seventy and his heart problems, which had plagued him for his entire presidency, were growing more persistent. His doctors prescribed rest and a withdrawal from public life, and after his term was finished Eisenhower intended to oblige them.

That left his Vice President, Richard Nixon of California, as the presumptive nominee for the party. The only opposition he faced during the primaries was from Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York and former Senator George Bender of Ohio. Despite their efforts, Nixon cruised to victory with 86% of the primary vote and was declared the nominee on the first ballot at the Republican National Convention.

Interested in presenting as strong a face on foreign policy as Eisenhower had, Nixon chose UN Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. of Massachusetts as his running mate. Overall the ticket was well received by the base and the Republican party looked to be in a good position to win a third consecutive term.

The Democratic primaries were more chaotic. While some hoped that John F. Kennedy would jump into the fray, he instead put his efforts into his work at the Senate, leading some to believe that he was aiming instead for 1964 or even 1968. Besides, with the landslide defeat of 1956 weighing heavily on the party's conscience, Kennedy lacked the sort of deep and popular support that would have been necessary for him to win the nomination.

The main contenders for the Democratic nomination were deeply split by geographic differences, with the south providing a frontrunner in the form of Senator Lyndon Johnson of Texas. Johnson, renowned and feared for his political acumen, had embraced largely populist policies and remained silent on civil rights, walking the tightrope between the growing portion of the party that was sympathetic to the plight of African Americans, and the segregationists who he depended upon for political support.

Nipping at Johnson's heels were the two main northern figures, Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri and Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota. Humphrey, while popular amongst workers and the lower class, still attracted controversy like a lightning rod due to his outspoken support for the Civil Rights movement, a handicap which Symington shared.

Adlai Stevenson also made a token effort to win the nomination, but faced with a lack of support after two consecutive landslide losses, he soon found himself out of the running. Instead, coming into the convention, the frontrunner proved to be Lyndon Johnson, who had effectively monopolized the entire south and made surprising inroads into the north. Though Humphrey and Symington united to stop him, Johnson secured victory on the second ballot and was nominated shortly afterwards.

However, even if they had united to place him onto the ticket, there was concern over Johnson's dedication to maintaining 'southern values' in the face of a growing national discussion over Civil Rights. Johnson wished to endorse a northern running mate (later it would be revealed that Symington was at the top of his personal list) but growing pressure from the southern delegates forced him to take an alternate route and support the nomination of Senator George Smathers of Florida.

Smathers had countless connectons to high level figures in Washington and Johnson hoped that by choosing the Floridian he would both assuage his southern base and foster a potential launchpad for relations between the various factions present within the party.

With the tickets set, the campaign began. Nixon, for his part, ran a positive campaign emphasizing the good that the Eisenhower administration had done for the nation and promising that he would deliver the same sort of growth and prosperity should he be elected.

Johnson's campaign was harsher and more dirty, which dismayed Smathers, who was a personal friend of Nixon and hated being part of what was sometimes borderline slander against the Vice President. This strained relations between Johnson and Smathers and by October the two men barely spoke to one another outside of campaign meetings. Nixon and Lodge on the other hand got along well, and even if Nixon was criticized for being wooden and occasionally uninspiring, the Republican ticket generally seemed to be the better option for many Americans who were sick of the mudslinging that was occurring.

In the October debates Johnson won a swift victory over Nixon in the first debate, which was also the first to be televised. Nixon retaliated by defeating Johnson in the second debate and holding the Texan to a draw in the third. Lodge and Smathers achieved a draw in the vice presidential debate, which ended up seeming more like a friendly chat than a political debate. Nixon's polling hung steady, and though Johnson had made a valiant effort, in the end it was Richard Nixon that carried the day.

Vice President Richard Nixon/UN Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. - 369 EV

Senator Lyndon Johnson/Senator George Smathers - 168 EV

Eisenhower's second term got off to a smooth start with the approval of the 'Eisenhower Doctrine' for regards to diplomacy in the Middle East, and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, which was passed by congress despite a record twenty five hour filibuster by Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina.

However, unforeseen events would soon put a damper on the popular President's administration. The first of these was the launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union, which would prompt Eisenhower to advocate for a civilian space flight agency to be created. The second was a minor recession, which would last for much of the remainder of his presidency. The third was the downing of a U2 observation plane over the Soviet Union. The only silver lining of what became a serious international scandal was that the pilot, a certain Gary Powers, was killed during the destruction of his aircraft. Despite these incidents, Eisenhower remained popular and there were rumblings of support for a repeal of the 22nd Amendment as the 1960 election approached.

These never became more than theoretical however, and it is unlikely that a repeal effort would have passed even if Eisenhower had offered the attempt his public support. Besides, Eisenhower was nearly seventy and his heart problems, which had plagued him for his entire presidency, were growing more persistent. His doctors prescribed rest and a withdrawal from public life, and after his term was finished Eisenhower intended to oblige them.

That left his Vice President, Richard Nixon of California, as the presumptive nominee for the party. The only opposition he faced during the primaries was from Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York and former Senator George Bender of Ohio. Despite their efforts, Nixon cruised to victory with 86% of the primary vote and was declared the nominee on the first ballot at the Republican National Convention.

Interested in presenting as strong a face on foreign policy as Eisenhower had, Nixon chose UN Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. of Massachusetts as his running mate. Overall the ticket was well received by the base and the Republican party looked to be in a good position to win a third consecutive term.

The Democratic primaries were more chaotic. While some hoped that John F. Kennedy would jump into the fray, he instead put his efforts into his work at the Senate, leading some to believe that he was aiming instead for 1964 or even 1968. Besides, with the landslide defeat of 1956 weighing heavily on the party's conscience, Kennedy lacked the sort of deep and popular support that would have been necessary for him to win the nomination.

The main contenders for the Democratic nomination were deeply split by geographic differences, with the south providing a frontrunner in the form of Senator Lyndon Johnson of Texas. Johnson, renowned and feared for his political acumen, had embraced largely populist policies and remained silent on civil rights, walking the tightrope between the growing portion of the party that was sympathetic to the plight of African Americans, and the segregationists who he depended upon for political support.

Nipping at Johnson's heels were the two main northern figures, Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri and Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota. Humphrey, while popular amongst workers and the lower class, still attracted controversy like a lightning rod due to his outspoken support for the Civil Rights movement, a handicap which Symington shared.

Adlai Stevenson also made a token effort to win the nomination, but faced with a lack of support after two consecutive landslide losses, he soon found himself out of the running. Instead, coming into the convention, the frontrunner proved to be Lyndon Johnson, who had effectively monopolized the entire south and made surprising inroads into the north. Though Humphrey and Symington united to stop him, Johnson secured victory on the second ballot and was nominated shortly afterwards.

However, even if they had united to place him onto the ticket, there was concern over Johnson's dedication to maintaining 'southern values' in the face of a growing national discussion over Civil Rights. Johnson wished to endorse a northern running mate (later it would be revealed that Symington was at the top of his personal list) but growing pressure from the southern delegates forced him to take an alternate route and support the nomination of Senator George Smathers of Florida.

Smathers had countless connectons to high level figures in Washington and Johnson hoped that by choosing the Floridian he would both assuage his southern base and foster a potential launchpad for relations between the various factions present within the party.

With the tickets set, the campaign began. Nixon, for his part, ran a positive campaign emphasizing the good that the Eisenhower administration had done for the nation and promising that he would deliver the same sort of growth and prosperity should he be elected.

Johnson's campaign was harsher and more dirty, which dismayed Smathers, who was a personal friend of Nixon and hated being part of what was sometimes borderline slander against the Vice President. This strained relations between Johnson and Smathers and by October the two men barely spoke to one another outside of campaign meetings. Nixon and Lodge on the other hand got along well, and even if Nixon was criticized for being wooden and occasionally uninspiring, the Republican ticket generally seemed to be the better option for many Americans who were sick of the mudslinging that was occurring.

In the October debates Johnson won a swift victory over Nixon in the first debate, which was also the first to be televised. Nixon retaliated by defeating Johnson in the second debate and holding the Texan to a draw in the third. Lodge and Smathers achieved a draw in the vice presidential debate, which ended up seeming more like a friendly chat than a political debate. Nixon's polling hung steady, and though Johnson had made a valiant effort, in the end it was Richard Nixon that carried the day.

Vice President Richard Nixon/UN Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. - 369 EV

Senator Lyndon Johnson/Senator George Smathers - 168 EV

The Curveball: Part 3

When he was inaugurated on January 20, 1961, Richard Nixon became the eleventh Vice President to ascend to the presidency, and the thirty fifth President overall. He came into office with a 60% approval rating, a booming economy and a raft of campaign promises that greatly excited the American people.

It didn't take long before things got incredibly muddled. While some of Nixon's plans for the nation were popular, like increased funding for NASA in order to combat the Soviets in the Space Race, others, like ignoring Civil Rights, were less well received.

While Nixon was perfectly content to let congress and the courts work Civil Rights out on their own without getting involved himself, others were less inclined to do so. One of these others was Vice President Lodge, who had attracted controversy on the campaign trail when he promised that Nixon would appoint at least one black cabinet member and remained much more pro-Civil Rights than his boss.

While Nixon did not completely uphold Lodge's promise, he did appoint Ralph Bunche to become Undersecretary of State, a relatively invisible but still quite powerful position for an African American in those days. He also supported desegregation, though was remarkably quiet about it, for fear of provoking the wrath of the Democratic dominated congress, which in turn was dominated by the southern segregationist bloc.

At the head of that bloc was Lyndon Johnson, who had more or less thrown his lot in with them through his efforts during the 1960 election. Privately though, Johnson had doubts about the continued viability of racism as a political tactic and began to quietly move to a more liberal position on race as time went on.

Instead he became much like Nixon in regards to race as 1961 passed, and as the President began to pass a moderate agenda through congress he and Johnson once again began to cross paths. Despite being from different parties, and having fought a nasty campaign against one another mere months before, their relationship was surprisingly cordial. Johnson was already walking a tightrope between the increasingly unruly segregationists and the rest of the party, and simply didn't have the energy to fight Nixon as hard as he wanted to. Besides, he was getting to sort of like the man.

As different as they were, both men had grown up poor and worked their way to power based upon their own merits. They shared an almost pathological dislike of elitism, and though Johnson was extroverted and boisterous in contrast to Nixon's more reserved introversion, the two men slowly began to get along as Nixon's term progressed.

Outside of domestic affairs, things were rockier for the Nixon administration. Though they succeeded in launching a man into orbit before the Soviets, the USSR managed to send an unmanned orbiter around the moon later that same year, frightening many at NASA. Relations between the US and the USSR also were perceived as declining, especially when the Soviet Union began to send advisors and military aid to the newly communist Castro regime in Cuba.

The Joint Chiefs advised Nixon to invade in response to these aggressions, a matter on which Nixon sought the advice of Eisenhower. The old commander in chief was hesitant to commit American troops, especially to a potential flash point like Cuba, but in the end the voices in the Nixon administration in favor of invasion outweighed Eisenhower's input, and following a messy and failed invasion of ex-pats that was allegedly put together by the CIA, Nixon sent in the Marines.

The subjugation of Cuba was swift, and cut off from any nearby source of weapons and other supplies, the Castro regime folded, both brothers being killed in the fighting, along with their disciple Che Guevara. By the end of 1962 Cuba was entirely in the hands of the United States, leaving the Soviet Union absolutely furious.

One indirect victim of the Cuban War was Premier Khrushchev, who fell victim to what many would later describe as a bloodless coup by Leonid Brezhnev and other, more hawkish Soviet politicians. One of Brezhnev's first actions as Premier was to beef up Soviet defenses in Eastern Europe, and to begin the action of building a wall around West Berlin. This was condemned by the Nixon administration, but ultimately they were powerless to stop it.

In the end though, despite being messy and costing the lives of nearly six hundred American soldiers, Marines and airmen between 1962 and 1964, when the last soldiers left, the Cuban War was perceived as a major victory for the Nixon administration and indeed the nation as a whole. The 1962 midterms would end up being one of those rare elections where the balance of power would not actually change, leaving the Democrats frustrated but still in control of healthy majorities in both houses.

Outside of the western hemisphere Nixon was also facing immense challenges, the foremost of them being Vietnam. Ever since the French had been defeated there in the late 1950s the nation had remained divided between a northern communist dictatorship and a southern capitalist dictatorship. Eisenhower had supported the French in their efforts to defeat the northern communists, and remained of the opinion that further action was needed there to make sure that the south remained free, but Nixon was ambivalent.

He viewed the South Vietnamese as largely corrupt and not worth helping. Instead he focused his efforts on surrounding nations, remarking to his cabinet officers that the United States was better off helping nations that had a chance of surviving the decade. This isn't to say that the South Vietnamese were abandoned by the Nixon administration, but the fact that they did not survive past 1965 before being forced to adhere to a referendum by Ho Chi Minh and subsequently join with the north was demonstrative of their lack of internal strength.

Avoiding entanglement in Vietnam, Nixon instead focused on Malaysia, Cambodia and Laos, hoping to confine the communists to Vietnam alone. Nixon didn't necessarily believe, like Curtis LeMay and so many others, that the Cold War could be won through military means. Instead he hoped that Vietnam and the other nations unfortunate enough to have embraced communism could one day be reformed into capitalist societies, once the people had realized their mistake and the communist system collapsed under its own weight.

This, while probably smarter than outright war, was less popular with the American people, who were concerned about what they viewed as Nixon purposefully letting communism spread. Fortunately, Nixon had his Cuba laurels to rest upon and most of this criticism didn't stick, allowing Nixon to remain moderately popular as it came time for him to decide whether or not he was going to stand for reelection.

While Nixon did in fact wish to run for another term, this was complicated by the actions of Henry Lodge. Lodge had proven to be a largely uninspiring Vice President, and though he had been helpful when it came to foreign policy advice, Nixon was growing heartily sick of some of the unwanted public input that Lodge was putting into the public sphere concerning Civil Rights and other social conventions.

Lodge too was beginning to grow unhappy with his post and in late November of 1963, shortly after a stormy meeting concerning the administration's response to a fiery white supremacist speech by Senator Stennis of Mississippi, Nixon took Lodge aside for a private conversation. No record survives of what exactly was said, and neither man detailed the discussion in their memoirs, but at the end of it Lodge agreed to resign his office at the convention in return for his old UN post back.

This left Nixon with some breathing room, but it was not long until that was snatched up by a new threat. This came from the conservative wing of the party, led by Barry Goldwater and a famous actor named Ronald Reagan, who decried Nixon for 'abandoning the Vietnamese people' and cuddling up to the communists in a hundred different and sensationalistic ways. Though Nixon had probably one of the most thoroughly anti-communist records of any President in history, his responses to the attacks was characteristically stiff and blustery, and Goldwater began to pick up steam as the primaries began.

He was to become a rather persistent thorn in Nixon's side for the next few months. Ronald Reagan as well, who had become rather enamored by the political game and desired to take a larger part in it. This wouldn't end well for either of the men, or their allies. Though Nixon wasn't the best with the press, or even the public for that matter, he was still popular with the party at large, and when it came to the primaries Goldwater only won his home state of Arizona before dropping out, having amassed only nineteen percent of the popular primary vote.

This repudiation of the conservatives extended to the convention, where Nixon twisted the knife by selecting moderate House Minority Leader Gerald Ford as his running mate. Though Ford was somewhat reluctant to take the post, wishing instead to stay in congress and become Speaker one day, he agreed and was nominated on the first ballot.

The Democratic primaries were uglier, as they did not have a strong incumbent to rally around like the Republicans. Instead some old faces appeared, along with new figures intent on stirring the pot. During Nixon's first term the Democratic party had begun to split along the seams, a quasi civil war erupting between the segregationists and virtually everyone else. Johnson had jumped ship after the 1962 midterms, and betrayed by his dismissal of their faction, the social conservatives had instead found a new figurehead in the form of Alabama governor George Wallace.

Wallace was economically moderate enough to attract votes from virtually all factions of the party, but still conservative enough on racial issues to appease the KKK and their supporters, which made him a serious threat in the south and even some of the states beyond.

Besides Wallace a small host of others had staked their claim in the hopes of winning the nomination and facing Nixon in the main election. Even though Nixon was popular, the Republican party had hung onto the White House for twelve years now and voter fatigue was expected to set in at any moment.

The most well known of these Democratic candidates was Hubert Humphrey, a veteran of the 1960 primaries who was now back for Round Two. Governor Pat Brown of California had also thrown his hat into the ring, threatening Humphrey's hold on the liberal faction of the party. To represent the hawks, Senator Henry 'Scoop' Jackson of Washington had jumped into the race as well. He held a commanding lead with the hawkish portion of the party, and was liberal enough on Civil Rights to win a wide range of voters.

All in all, the various candidates were evenly matched, which made the primaries a slog. While they fought and quarreled over economics, welfare and foreign policy, virtually everyone except for George Wallace was on the same page when it came to Civil Rights, which led to a fantastically one sided debate where each candidate took turns pummeling Wallace on the issue of segregation. Wallace would grin and take his punishment like a champ, but his charisma simply wasn't enough for him to take home the nomination.

Instead, upon dropping out of the race and pledging his delegates to nobody, he took the step of forming his own political party, partially out of ambition and partially out of spite. He called it the American Independent Party and chose Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina as his running mate.

This concerned many, and though Humphrey and Brown would score major points by decrying this move and calling Wallace a hundred different variations of 'traitor', in the end it would not be enough to save them from being outmaneuvered by Senator Jackson, whose foreign policy acumen was deeply attractive to voters who were worried about conflict with the Soviets and the communists in southern Asia.

Jackson would be nominated at the Democratic National Convention on the second ballot. Privately he made overtures to George Wallace, hoping to heal the rift in the party before it could become a full blown schism, but Wallace was bellicose enough that Jackson hung up, famously muttering something about Wallace making him wish that Sherman had had nuclear weapons during his March to the Sea.

Instead, hesitant to choose Humphrey because of some of his foreign policy views, Jackson chose Governor John Reynolds Jr. of Wisconsin, who had strong domestic credentials and wouldn't overshadow him on the campaign trail. Though Humphrey was miffed at being passed up for running mate, he endorsed the ticket along with most of the party and got ready to watch the campaign begin for real.

Nixon held a definite lead over the other tickets as the campaign began, and this wouldn't change for most of the rest of the campaign. Wallace's third ticket presence had split the Democrats badly and their red hot outrage at the mainstream party's acceptance of Civil Rights had invigorated many ordinary people, most in the south, who were dismayed at the idea of integration and what Wallace described as 'Stalinist racial quotas' and Thurmond so eloquently described as 'Nigras takin' your jobs!'

While this was definitely an advantage for Nixon, he was privately disgusted by Wallace and Thurmond's bid to maintain Jim Crow in the south, especially as he began spending more time with Vice President Ford, who was undoubtedly pro-Civil Rights. Though he would maintain his silence on Civil Rights, something had been stirred in him, and privately Nixon began to talk to some people about small steps that could be taken after the election in order to quash the influence of Wallace and Thurmond in the south.

Though some of his advisors mentioned that there was a chance to denounce Civil Rights altogether and win a landslide by stealing away the south from the Democratic party, Nixon dismissed that strategy. After the trouble that the conservative faction of his own party had given him only a few months before, he didn't want to do anything that would swell their numbers.

Instead he campaigned on the economic growth that the nation was experiencing, the responsible regulation and flexible rules that kept capitalism healthy and how communists all across the world were on the run. It was largely an extension of his 1960 campaign, and once again the average American quite enjoyed it.

Jackson and Reynolds' message was more focused upon how the underprivileged of the nation still needed to be helped. They spoke of establishing a national social insurance program, a national healthcare program and other issues that excited many liberals in the nation. Johnson and Humphrey had been a large part of dragging these into the party platform, and it paid off. The idea of a national social insurance program in particular was broadly popular and Nixon was quick to promise that he would work with Democrats in congress to pass such a program if reelected. This blunted the worst of the Democratic attacks against him, and as fall began it was time for the debates to begin.

Much like 1960, the two debaters were evenly matched, and it showed when they managed to achieve draws for all three debates. Jackson was polite and courteous throughout these debates and Nixon would grow to enjoy his company, the two men would become friends later in life, after both had left politics.

In the vice presidential debate Ford managed to trounce Reynolds, who made a number of gaffes and sunk Democratic polls by several points. This damaged Democratic chances in the Midwest and it showed when the election rolled around. Though the Democrats had fought hard to take back the White House, their schism with the segregationists in their midst made victory all but impossible, and so Nixon secured his reelection.

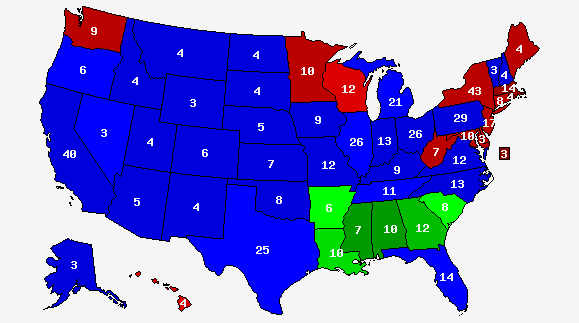

President Richard Nixon/Vice President Gerald Ford - 337 EV

Senator Henry Jackson/Governor John Reynolds Jr. - 148 EV

Governor George Wallace/Senator Strom Thurmond - 53 EV

When he was inaugurated on January 20, 1961, Richard Nixon became the eleventh Vice President to ascend to the presidency, and the thirty fifth President overall. He came into office with a 60% approval rating, a booming economy and a raft of campaign promises that greatly excited the American people.

It didn't take long before things got incredibly muddled. While some of Nixon's plans for the nation were popular, like increased funding for NASA in order to combat the Soviets in the Space Race, others, like ignoring Civil Rights, were less well received.

While Nixon was perfectly content to let congress and the courts work Civil Rights out on their own without getting involved himself, others were less inclined to do so. One of these others was Vice President Lodge, who had attracted controversy on the campaign trail when he promised that Nixon would appoint at least one black cabinet member and remained much more pro-Civil Rights than his boss.

While Nixon did not completely uphold Lodge's promise, he did appoint Ralph Bunche to become Undersecretary of State, a relatively invisible but still quite powerful position for an African American in those days. He also supported desegregation, though was remarkably quiet about it, for fear of provoking the wrath of the Democratic dominated congress, which in turn was dominated by the southern segregationist bloc.

At the head of that bloc was Lyndon Johnson, who had more or less thrown his lot in with them through his efforts during the 1960 election. Privately though, Johnson had doubts about the continued viability of racism as a political tactic and began to quietly move to a more liberal position on race as time went on.

Instead he became much like Nixon in regards to race as 1961 passed, and as the President began to pass a moderate agenda through congress he and Johnson once again began to cross paths. Despite being from different parties, and having fought a nasty campaign against one another mere months before, their relationship was surprisingly cordial. Johnson was already walking a tightrope between the increasingly unruly segregationists and the rest of the party, and simply didn't have the energy to fight Nixon as hard as he wanted to. Besides, he was getting to sort of like the man.

As different as they were, both men had grown up poor and worked their way to power based upon their own merits. They shared an almost pathological dislike of elitism, and though Johnson was extroverted and boisterous in contrast to Nixon's more reserved introversion, the two men slowly began to get along as Nixon's term progressed.

Outside of domestic affairs, things were rockier for the Nixon administration. Though they succeeded in launching a man into orbit before the Soviets, the USSR managed to send an unmanned orbiter around the moon later that same year, frightening many at NASA. Relations between the US and the USSR also were perceived as declining, especially when the Soviet Union began to send advisors and military aid to the newly communist Castro regime in Cuba.

The Joint Chiefs advised Nixon to invade in response to these aggressions, a matter on which Nixon sought the advice of Eisenhower. The old commander in chief was hesitant to commit American troops, especially to a potential flash point like Cuba, but in the end the voices in the Nixon administration in favor of invasion outweighed Eisenhower's input, and following a messy and failed invasion of ex-pats that was allegedly put together by the CIA, Nixon sent in the Marines.

The subjugation of Cuba was swift, and cut off from any nearby source of weapons and other supplies, the Castro regime folded, both brothers being killed in the fighting, along with their disciple Che Guevara. By the end of 1962 Cuba was entirely in the hands of the United States, leaving the Soviet Union absolutely furious.

One indirect victim of the Cuban War was Premier Khrushchev, who fell victim to what many would later describe as a bloodless coup by Leonid Brezhnev and other, more hawkish Soviet politicians. One of Brezhnev's first actions as Premier was to beef up Soviet defenses in Eastern Europe, and to begin the action of building a wall around West Berlin. This was condemned by the Nixon administration, but ultimately they were powerless to stop it.

In the end though, despite being messy and costing the lives of nearly six hundred American soldiers, Marines and airmen between 1962 and 1964, when the last soldiers left, the Cuban War was perceived as a major victory for the Nixon administration and indeed the nation as a whole. The 1962 midterms would end up being one of those rare elections where the balance of power would not actually change, leaving the Democrats frustrated but still in control of healthy majorities in both houses.

Outside of the western hemisphere Nixon was also facing immense challenges, the foremost of them being Vietnam. Ever since the French had been defeated there in the late 1950s the nation had remained divided between a northern communist dictatorship and a southern capitalist dictatorship. Eisenhower had supported the French in their efforts to defeat the northern communists, and remained of the opinion that further action was needed there to make sure that the south remained free, but Nixon was ambivalent.

He viewed the South Vietnamese as largely corrupt and not worth helping. Instead he focused his efforts on surrounding nations, remarking to his cabinet officers that the United States was better off helping nations that had a chance of surviving the decade. This isn't to say that the South Vietnamese were abandoned by the Nixon administration, but the fact that they did not survive past 1965 before being forced to adhere to a referendum by Ho Chi Minh and subsequently join with the north was demonstrative of their lack of internal strength.

Avoiding entanglement in Vietnam, Nixon instead focused on Malaysia, Cambodia and Laos, hoping to confine the communists to Vietnam alone. Nixon didn't necessarily believe, like Curtis LeMay and so many others, that the Cold War could be won through military means. Instead he hoped that Vietnam and the other nations unfortunate enough to have embraced communism could one day be reformed into capitalist societies, once the people had realized their mistake and the communist system collapsed under its own weight.

This, while probably smarter than outright war, was less popular with the American people, who were concerned about what they viewed as Nixon purposefully letting communism spread. Fortunately, Nixon had his Cuba laurels to rest upon and most of this criticism didn't stick, allowing Nixon to remain moderately popular as it came time for him to decide whether or not he was going to stand for reelection.

While Nixon did in fact wish to run for another term, this was complicated by the actions of Henry Lodge. Lodge had proven to be a largely uninspiring Vice President, and though he had been helpful when it came to foreign policy advice, Nixon was growing heartily sick of some of the unwanted public input that Lodge was putting into the public sphere concerning Civil Rights and other social conventions.

Lodge too was beginning to grow unhappy with his post and in late November of 1963, shortly after a stormy meeting concerning the administration's response to a fiery white supremacist speech by Senator Stennis of Mississippi, Nixon took Lodge aside for a private conversation. No record survives of what exactly was said, and neither man detailed the discussion in their memoirs, but at the end of it Lodge agreed to resign his office at the convention in return for his old UN post back.

This left Nixon with some breathing room, but it was not long until that was snatched up by a new threat. This came from the conservative wing of the party, led by Barry Goldwater and a famous actor named Ronald Reagan, who decried Nixon for 'abandoning the Vietnamese people' and cuddling up to the communists in a hundred different and sensationalistic ways. Though Nixon had probably one of the most thoroughly anti-communist records of any President in history, his responses to the attacks was characteristically stiff and blustery, and Goldwater began to pick up steam as the primaries began.

He was to become a rather persistent thorn in Nixon's side for the next few months. Ronald Reagan as well, who had become rather enamored by the political game and desired to take a larger part in it. This wouldn't end well for either of the men, or their allies. Though Nixon wasn't the best with the press, or even the public for that matter, he was still popular with the party at large, and when it came to the primaries Goldwater only won his home state of Arizona before dropping out, having amassed only nineteen percent of the popular primary vote.

This repudiation of the conservatives extended to the convention, where Nixon twisted the knife by selecting moderate House Minority Leader Gerald Ford as his running mate. Though Ford was somewhat reluctant to take the post, wishing instead to stay in congress and become Speaker one day, he agreed and was nominated on the first ballot.

The Democratic primaries were uglier, as they did not have a strong incumbent to rally around like the Republicans. Instead some old faces appeared, along with new figures intent on stirring the pot. During Nixon's first term the Democratic party had begun to split along the seams, a quasi civil war erupting between the segregationists and virtually everyone else. Johnson had jumped ship after the 1962 midterms, and betrayed by his dismissal of their faction, the social conservatives had instead found a new figurehead in the form of Alabama governor George Wallace.

Wallace was economically moderate enough to attract votes from virtually all factions of the party, but still conservative enough on racial issues to appease the KKK and their supporters, which made him a serious threat in the south and even some of the states beyond.

Besides Wallace a small host of others had staked their claim in the hopes of winning the nomination and facing Nixon in the main election. Even though Nixon was popular, the Republican party had hung onto the White House for twelve years now and voter fatigue was expected to set in at any moment.

The most well known of these Democratic candidates was Hubert Humphrey, a veteran of the 1960 primaries who was now back for Round Two. Governor Pat Brown of California had also thrown his hat into the ring, threatening Humphrey's hold on the liberal faction of the party. To represent the hawks, Senator Henry 'Scoop' Jackson of Washington had jumped into the race as well. He held a commanding lead with the hawkish portion of the party, and was liberal enough on Civil Rights to win a wide range of voters.

All in all, the various candidates were evenly matched, which made the primaries a slog. While they fought and quarreled over economics, welfare and foreign policy, virtually everyone except for George Wallace was on the same page when it came to Civil Rights, which led to a fantastically one sided debate where each candidate took turns pummeling Wallace on the issue of segregation. Wallace would grin and take his punishment like a champ, but his charisma simply wasn't enough for him to take home the nomination.

Instead, upon dropping out of the race and pledging his delegates to nobody, he took the step of forming his own political party, partially out of ambition and partially out of spite. He called it the American Independent Party and chose Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina as his running mate.

This concerned many, and though Humphrey and Brown would score major points by decrying this move and calling Wallace a hundred different variations of 'traitor', in the end it would not be enough to save them from being outmaneuvered by Senator Jackson, whose foreign policy acumen was deeply attractive to voters who were worried about conflict with the Soviets and the communists in southern Asia.

Jackson would be nominated at the Democratic National Convention on the second ballot. Privately he made overtures to George Wallace, hoping to heal the rift in the party before it could become a full blown schism, but Wallace was bellicose enough that Jackson hung up, famously muttering something about Wallace making him wish that Sherman had had nuclear weapons during his March to the Sea.

Instead, hesitant to choose Humphrey because of some of his foreign policy views, Jackson chose Governor John Reynolds Jr. of Wisconsin, who had strong domestic credentials and wouldn't overshadow him on the campaign trail. Though Humphrey was miffed at being passed up for running mate, he endorsed the ticket along with most of the party and got ready to watch the campaign begin for real.

Nixon held a definite lead over the other tickets as the campaign began, and this wouldn't change for most of the rest of the campaign. Wallace's third ticket presence had split the Democrats badly and their red hot outrage at the mainstream party's acceptance of Civil Rights had invigorated many ordinary people, most in the south, who were dismayed at the idea of integration and what Wallace described as 'Stalinist racial quotas' and Thurmond so eloquently described as 'Nigras takin' your jobs!'

While this was definitely an advantage for Nixon, he was privately disgusted by Wallace and Thurmond's bid to maintain Jim Crow in the south, especially as he began spending more time with Vice President Ford, who was undoubtedly pro-Civil Rights. Though he would maintain his silence on Civil Rights, something had been stirred in him, and privately Nixon began to talk to some people about small steps that could be taken after the election in order to quash the influence of Wallace and Thurmond in the south.

Though some of his advisors mentioned that there was a chance to denounce Civil Rights altogether and win a landslide by stealing away the south from the Democratic party, Nixon dismissed that strategy. After the trouble that the conservative faction of his own party had given him only a few months before, he didn't want to do anything that would swell their numbers.

Instead he campaigned on the economic growth that the nation was experiencing, the responsible regulation and flexible rules that kept capitalism healthy and how communists all across the world were on the run. It was largely an extension of his 1960 campaign, and once again the average American quite enjoyed it.

Jackson and Reynolds' message was more focused upon how the underprivileged of the nation still needed to be helped. They spoke of establishing a national social insurance program, a national healthcare program and other issues that excited many liberals in the nation. Johnson and Humphrey had been a large part of dragging these into the party platform, and it paid off. The idea of a national social insurance program in particular was broadly popular and Nixon was quick to promise that he would work with Democrats in congress to pass such a program if reelected. This blunted the worst of the Democratic attacks against him, and as fall began it was time for the debates to begin.

Much like 1960, the two debaters were evenly matched, and it showed when they managed to achieve draws for all three debates. Jackson was polite and courteous throughout these debates and Nixon would grow to enjoy his company, the two men would become friends later in life, after both had left politics.

In the vice presidential debate Ford managed to trounce Reynolds, who made a number of gaffes and sunk Democratic polls by several points. This damaged Democratic chances in the Midwest and it showed when the election rolled around. Though the Democrats had fought hard to take back the White House, their schism with the segregationists in their midst made victory all but impossible, and so Nixon secured his reelection.

President Richard Nixon/Vice President Gerald Ford - 337 EV

Senator Henry Jackson/Governor John Reynolds Jr. - 148 EV

Governor George Wallace/Senator Strom Thurmond - 53 EV

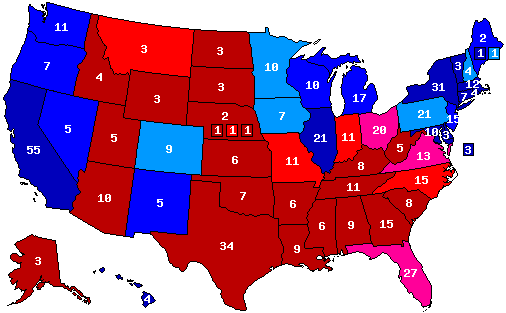

Okay, here's a possible 2016 electoral map.

Democratic: Hillary Clinton (New York)/Martin O'Malley (Maryland) - 277 EVs

Republican: Chris Christie (New Jersey)/Marco Rubio (Florida) - 241 EVs

So here's a rundown of what I did:

I created a 2012 "basemap" by bringing both Obama and Romney's percentages to 50% by adding 2.8% to Romney's votes in each state and taking away 1.06% from Obama's. I then took 2.5% from Romney in Massachusetts and gave an additional 2.5% to Obama, and did the reverse in Illinois. I also took away 1.25% from Romney in Wisconsin and gave 1.25% to Obama, and did the reverse in Delaware.

Once I had the basemap created, I used the "Trend" map from Dave Leip's US Election Atlas for the 2012 presidential election to add or take away votes from each party in each state.

Finally, I added 2.5% to Clinton in New York and took 2.5% away from Christie, did the reverse in New Jersey, and took 1.25% from Christie in Maryland and gave 1.25% to Clinton, and did the reverse in Florida. I also added 1% point to the GOP in California, Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas to account for the Christie/Rubio ticket being more liberal on immigration.

Interestingly, Pennsylvania ends up as a tie in this scenario, though the Democrats still win without it.

Democratic: Hillary Clinton (New York)/Martin O'Malley (Maryland) - 277 EVs

Republican: Chris Christie (New Jersey)/Marco Rubio (Florida) - 241 EVs

So here's a rundown of what I did:

I created a 2012 "basemap" by bringing both Obama and Romney's percentages to 50% by adding 2.8% to Romney's votes in each state and taking away 1.06% from Obama's. I then took 2.5% from Romney in Massachusetts and gave an additional 2.5% to Obama, and did the reverse in Illinois. I also took away 1.25% from Romney in Wisconsin and gave 1.25% to Obama, and did the reverse in Delaware.

Once I had the basemap created, I used the "Trend" map from Dave Leip's US Election Atlas for the 2012 presidential election to add or take away votes from each party in each state.

Finally, I added 2.5% to Clinton in New York and took 2.5% away from Christie, did the reverse in New Jersey, and took 1.25% from Christie in Maryland and gave 1.25% to Clinton, and did the reverse in Florida. I also added 1% point to the GOP in California, Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas to account for the Christie/Rubio ticket being more liberal on immigration.

Interestingly, Pennsylvania ends up as a tie in this scenario, though the Democrats still win without it.

Last edited:

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: