No, sorry. I only have one F-104. I was intending to post it later. It has the standard wing.@Rickshaw - do you have perhaps a what-if F-104 with bigger/better wings?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alternate Aircraft of Nations

- Thread starter Count of Crisco

- Start date

Well up until the second world war there wasnt that big a performance gap. And also floats give you a greater ability to operate in remote areas as they dont need as much infastructure.You take a big hit in performance compared to a conventional aircraft though, if Norway is thinking about facing down an invasion it might need to be able to match performances?

Driftless

Donor

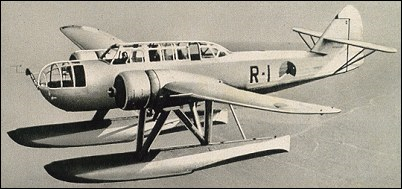

Go with the one they ordered, but weren't available till after the invasion: Norway's Northrup N3PB. Just have them ordered, delivered, and worked up by Feb 1940. It's primary mission was patrol, but it was also to be rigged for torpedos or bombs. Pretty quickly obsolescent, but it could have been very useful in April 1940

Interestingly they actually do require quite an infrastructure. You must continually clear your landing area to prevent foreign objects which might hole your floats from interfering in operation. Fjords look pretty but can be dangerous.Well up until the second world war there wasnt that big a performance gap. And also floats give you a greater ability to operate in remote areas as they dont need as much infastructure.

Cant imagine hitting chunks of floating ice on take off or landing speeds would be a good thing?Interestingly they actually do require quite an infrastructure. You must continually clear your landing area to prevent foreign objects which might hole your floats from interfering in operation. Fjords look pretty but can be dangerous.

True. But a seaplane may be an easier sell to the politicians who pay for it. And is more versatile in the period. Runways were a little few and far between in the area at the time.Interestingly they actually do require quite an infrastructure. You must continually clear your landing area to prevent foreign objects which might hole your floats from interfering in operation. Fjords look pretty but can be dangerous.

That's what you call a holy st$#* moment, or its equivalent Norwegian term in this instance.Cant imagine hitting chunks of floating ice on take off or landing speeds would be a good thing?

Driftless

Donor

Stealing an idea from CV(6)N's estimable timeline "Det som går ned må komme opp-An Alternate Royal Norwegian Navy TL"

The Fokker D.XXI for the Norwegian Luftsvaret in mid-1938. In that timeline, the engine of choice was the P&W R-1830, as that engine was used in other Norwegian aircraft. The Fokker was then current and available for export, and within the capabilities of the local military aviation establishment for assembly and repair. With it's fixed landing gear, it also was relatively easily adapted for skis, which would be useful on Norway's emergency airfields (frozen lakes and fields). With a purchase in 1938, there's sufficient opportunity for training with the aircraft during 1939 and early 1940.

The Fokker D.XXI for the Norwegian Luftsvaret in mid-1938. In that timeline, the engine of choice was the P&W R-1830, as that engine was used in other Norwegian aircraft. The Fokker was then current and available for export, and within the capabilities of the local military aviation establishment for assembly and repair. With it's fixed landing gear, it also was relatively easily adapted for skis, which would be useful on Norway's emergency airfields (frozen lakes and fields). With a purchase in 1938, there's sufficient opportunity for training with the aircraft during 1939 and early 1940.

Driftless

Donor

Interestingly they actually do require quite an infrastructure. You must continually clear your landing area to prevent foreign objects which might hole your floats from interfering in operation. Fjords look pretty but can be dangerous.

Cant imagine hitting chunks of floating ice on take off or landing speeds would be a good thing?

All valid points, but the Norwegians have used seaplanes and floatplanes all along their coast from the earliest days of heavier-than-air flight through to the present. Their naval air service even designed and built homegrown floatplanes during the interwar years. It was a necessity then with a largely rural country with an extremely long coast and limited space for land airfields, especially in the north.True. But a seaplane may be an easier sell to the politicians who pay for it. And is more versatile in the period. Runways were a little few and far between in the area at the time.

Shouldn't be a problem. If the Roc can use floats then a Skua could.With so many fjords surely float planes would be tempting?

A good aircraft for Norway would be the Fokker T.VIII if they could get them produced in time.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Fokker T.VIII - Wikipedia

Pangur

Donor

Like the idea. Their own production line maybe?A good aircraft for Norway would be the Fokker T.VIII if they could get them produced in time.

Fokker T.VIII - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

View attachment 608601

Not in Norway, but if Sweden gets interested in the aircraft it could be done there. Also if Norway is getting twitchy as early as 1936 then Fokker could start work designing the TVIII a year early at their request for a torpedo bomber float plane.Like the idea. Their own production line maybe?

A-4G Skyhawk in Royal Australian Marines service, New Guinea, 1978

The McDonnell Douglas A-4G Skyhawk is a variant of the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk attack aircraft developed for the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). The model was based on the A-4F variant of the Skyhawk, and was fitted with slightly different avionics as well as the capacity to operate AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles. The RAN received ten A-4Gs in 1967 and another ten in 1971, and operated the type from 1967 to 1984.

In Australian service the A-4Gs formed part of the air group of the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne, and were primarily used to provide air defence for the fleet. They took part in exercises throughout the Pacific region and also supported the training of RAN warships as well as other elements of the Australian military. The Skyhawks did not see combat, and a planned deployment of some of their pilots to fight in the Vietnam War was cancelled before it took place. Ten A-4Gs were destroyed as a result of equipment failures and non-combat crashes during the type's service with the Navy, causing the deaths of two pilots.

The RAN had no need for most of its fixed-wing aircraft after Melbourne was decommissioned in 1982. The remaining A-4Gs were assigned to the Royal Australian Marines air wing.

In 1975, the Royal Australian Marines also adopted the A-4G Skyhawk as their standard Close Air Support aircraft. Armed with a mix of Sidewinders, rocket pods and bombs, the A4-G was an able aircraft for use in supporting the Marines ashore. Able to be flown from small, forward airstrips and carriers, off shore, the A-4 was considered exactly the right sized platform for the Marines’ needs.

In 1978, the Marines were assigned to Papua-New Guinea’s defence against the Indonesians who occupred the western half of the Island, a legacy of the Dutch who had resigned their role as Colonists in 1964. Indonesia, under a Communist regime since 1965 had been antagonistic towards Australia in a “Cold War” like situation, ever since that country and the UK and New Zealand defended Malaysia during the Borneo Confrontation period.

Basing their new A-4Gs in small forward operating airstrips in the Owen Stanley valleys, the Marines undertook aggressive patrol along the border with West Irian, as the Indonesians called their half of the island. Occasional encounters occurred between the Indonesian special forces and the Marines and the A-4Gs proved their worth, carrying 500lb bombs, rocket pods and Sidewinder missiles for self-defence. Bombs and rockets were occasionally used in support of Marine ground patrols on the PNG side of the border but there were no reports of Marine air units crossing the land border with West Irian.

The Model

The model is a venerable Esci A-4E/F model in 1/72 scale. It has been brush painted in a hypothetical camouflage finish and decals came from the spares box, as did the two Sidewinder missiles on the outer wing pylons.

The McDonnell Douglas A-4G Skyhawk is a variant of the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk attack aircraft developed for the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). The model was based on the A-4F variant of the Skyhawk, and was fitted with slightly different avionics as well as the capacity to operate AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles. The RAN received ten A-4Gs in 1967 and another ten in 1971, and operated the type from 1967 to 1984.

In Australian service the A-4Gs formed part of the air group of the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne, and were primarily used to provide air defence for the fleet. They took part in exercises throughout the Pacific region and also supported the training of RAN warships as well as other elements of the Australian military. The Skyhawks did not see combat, and a planned deployment of some of their pilots to fight in the Vietnam War was cancelled before it took place. Ten A-4Gs were destroyed as a result of equipment failures and non-combat crashes during the type's service with the Navy, causing the deaths of two pilots.

The RAN had no need for most of its fixed-wing aircraft after Melbourne was decommissioned in 1982. The remaining A-4Gs were assigned to the Royal Australian Marines air wing.

In 1975, the Royal Australian Marines also adopted the A-4G Skyhawk as their standard Close Air Support aircraft. Armed with a mix of Sidewinders, rocket pods and bombs, the A4-G was an able aircraft for use in supporting the Marines ashore. Able to be flown from small, forward airstrips and carriers, off shore, the A-4 was considered exactly the right sized platform for the Marines’ needs.

In 1978, the Marines were assigned to Papua-New Guinea’s defence against the Indonesians who occupred the western half of the Island, a legacy of the Dutch who had resigned their role as Colonists in 1964. Indonesia, under a Communist regime since 1965 had been antagonistic towards Australia in a “Cold War” like situation, ever since that country and the UK and New Zealand defended Malaysia during the Borneo Confrontation period.

Basing their new A-4Gs in small forward operating airstrips in the Owen Stanley valleys, the Marines undertook aggressive patrol along the border with West Irian, as the Indonesians called their half of the island. Occasional encounters occurred between the Indonesian special forces and the Marines and the A-4Gs proved their worth, carrying 500lb bombs, rocket pods and Sidewinder missiles for self-defence. Bombs and rockets were occasionally used in support of Marine ground patrols on the PNG side of the border but there were no reports of Marine air units crossing the land border with West Irian.

The Model

The model is a venerable Esci A-4E/F model in 1/72 scale. It has been brush painted in a hypothetical camouflage finish and decals came from the spares box, as did the two Sidewinder missiles on the outer wing pylons.

The Saunders-Roe SR.177 Falcon in RAN service

In 1952, Saunders-Roe had been awarded a contract to develop a combined rocket-and-jet-propelled interceptor aircraft, which was designated as the Saunders-Roe SR.53. However, as development work on the project progressed, the shortcomings of the design became increasingly evident. Most particularly, as with the German rocket-powered interceptors of the Second World War, the range and endurance of such an aircraft were limited by the high rate of fuel consumption by the rocket engine. However, as turbojet engines developed and became increasingly powerful and efficient, new powerplants were quickly becoming available that would make such aircraft more practical.

Maurice Brennan, the chief designer of the SR.53, had also become convinced of the necessity for an airborne radar unit to be carried by the aircraft, as the SR.53 was reliant upon on ground-based radar guidance and the pilot's own vision to intercept aircraft. In particular, it was feared that pilots would be unable to focus their eyes properly at the 60,000 feet (18,000 m) altitude that the SR.53 was capable of. Out of a combined desire to equip the aircraft with a radar unit and to make greater use of turbojet power, a more ambitious design began to be drawn up. While it had begun as an advanced design concept for the SR.53, upon the issuing of a development contract by the Ministry of Defence in May 1955 (to meet specification F.155), the project was given its own designation as the SR.177.

As work continued on the SR.53, a separate High Speed Development Section was formed by Saunders-Roe to work on the SR.177. Initially, the SR.177 was a straighforward development of the SR.53, sharing much of the same configuration and equipment, and it was envisioned that the first test flight would take place during the first half of 1957. However, in February 1955, an extensive redesign of the SR.177, with the aim of making the type suitable for use by both the RAF and the Royal Navy, was commenced. Of the changes made to the aircraft, major differences included the repositioning of the jet engine to the lower fuselage lobe, which was now fed with air via a large, chin-mounted intake; the wing was also enlarged and blown flaps were adopted. The turbojet engine selected was the de Havilland Gyron Junior, capable of generating 8,000 lbf (36,000 N) of thrust.

Project launch

In September 1955, Saunders-Roe received instructions to proceed on the SR.177 from the British Ministry of Supply. The Ministry also gave instruction for the production of mock-ups, windtunnel tests, and the development of construction jigs for the manufacture of an initial batch of aircraft. From the onset, the SR.177 faced competition in the form of an enlarged derivative of the Avro 720, which had itself been devised as a competitor against the smaller SR.53. Avro promoted the 720 to the Royal Navy, hoping to win favour away from the SR.177, which was by this point had reached the detail design phase. The Ministry ultimately opted to cancel all work on the Avro 720, primarily as a cost-saving measure, as well as to concentrate development work on HTP-based rocket motors, such as those powering the SR.53 and SR.177.

The most significant difference between the SR.53 and SR.177 was the latter's use of a jet engine with nearly five times the thrust of the one adopted for the former. While the SR.53 had relied mostly on its rocket engine for climbing, the SR.177 would be able to add considerable endurance by conserving use of its rocket for the dash towards a target only. It was expected that the added endurance would allow the SR.177 to perform roles other than pure interception; these roles were expected to include strike and reconnaissance missions. The SR.53 design had been considerably enlarged to accommodate the new engine, and the original sleek lines were forfeited for the chin-mounted air intake.

Following the maiden flight of the SR.53 in May 1957, the development of the SR.177 became the main focus of activity at Saunders-Roe. At this point, the project was viewed as having considerable large scale potential, as both the RAF and Royal Navy appeared to be set to be customers for the SR.177. The RAF sought to operate it alongside the incoming English Electric Lightning interceptors while, according to aviation author Derek Wood, the Royal Navy also had considerable interest in the programme. When the development contract had been issued in May 1955, it reflected this dual interest. The Navy's requirements were defined in NA.47 while the RAF's requirements were specified in OR.337, which had been issued by the Ministry of Supply as Operational Requirement F.155. There was optimism that a joint aircraft for the two services could be developed, saving considerable expense, time, and effort.

Negotiations on the exact number of aircraft sought by either service were protracted; but it had been established that there was demand for an initial batch of 27 SR.177 aircraft, and that sufficient tooling should be produced to enable the programme to transition rapidly to full-rate production. By April 1956, a consensus had emerged that, in order for the first five SR.177s to be completed by January 1958, these aircraft would be produced without any A.I. radar or the ability to support armaments. In July 1956, funding was secured for 27 aircraft to be produced, the first of which being expected to fly by April (later postponed to October) 1958. On 4 September 1956, a formal contract for the 27 aircraft was issued, which was sub-divided into four batches of five, four, four, and fourteen respectively, although the final eighteen were subject to evaluation and were thus pending confirmation. During 1957, a development contract for the SR.177 was announced for its use with the Royal Navy.

By January 1957, the design of the main component jigs was 70 per cent complete while the component assembly jigs were almost 50 per cent complete; the manufacture of a quantity production batch was nearing, which would have likely been subcontracted to another aviation company due to the high level of workload at Saunders-Roe's Cowes facility. Armstrong Whitworth, who had already taken over work on the basic wing design of the SR.177, had been selected as the second production outlet for the type. The selection of a production center for the SR.177 was complicated by a favourable event; interest in the programme from the West German government. Since 1955, the revived German Air Force had sought a suitable high performance aircraft to equip itself with, and there were hopes that the SR.177 could become the foundation of a collaborative European fighter programme.

The German Defence Ministry had first expressed interest in the SR.177 in October 1955; in February 1956, the British Government Committee on Security consented to discussions being held on the SR.177. The prospects of a large German order for as many as 200 aircraft, and for the SR.177 to be manufactured under licence in Germany by the recovering German aircraft industry, were soon being aired, of which the British government declared its openness towards. In January 1957, the Anglo-German Standing Committee on Arms Supply reported that General Kammhuber, the Commander-in-Chief of the German Air Force, was concerned that, due to a lack of available financing until Aprril 1958, the delivery timetable may not be satisfactory. According to Wood, Germany was keen to issue an order as soon as possible by this point, which they did. They ordered 194 aircraft from Armstrong Whitworth who were contracting on behalf of Saunders-Roe.

With the German order other nations started to take increased interest in the SR.177 design. After Germany, Belgium ordered 48 aircraft, Holland another 60. From outside Europe, the Royal Australian Navy's Fleet Air Arm, anxious to move out of the piston-engined era at last, ordered 36 for service aboard its light fleet carriers, HMAS Sydney and Melbourne. The Royal New Zealand Air Force ordered 24. The South African Air Force ordered 60. The SR.177 was a success commercially, with the total ordered by the RAF (200) and the RN FAA (80). It served successfully in the Interceptor, Reconnaissance and Fighter-Bomber roles. Its only combat use was by the RSAF against black rebel groups fighting the Apartheid regime, where it was used to drop bombs and fire unguided rockets.

The Model

The model is the Freightdog SR.177 model. I added a spare arrestor hook under the rear fuselage and raided the decals box for RAN roundels and titles. It was painted with a hairy stick using Tamiya flat paints and then Future'd.

In 1952, Saunders-Roe had been awarded a contract to develop a combined rocket-and-jet-propelled interceptor aircraft, which was designated as the Saunders-Roe SR.53. However, as development work on the project progressed, the shortcomings of the design became increasingly evident. Most particularly, as with the German rocket-powered interceptors of the Second World War, the range and endurance of such an aircraft were limited by the high rate of fuel consumption by the rocket engine. However, as turbojet engines developed and became increasingly powerful and efficient, new powerplants were quickly becoming available that would make such aircraft more practical.

Maurice Brennan, the chief designer of the SR.53, had also become convinced of the necessity for an airborne radar unit to be carried by the aircraft, as the SR.53 was reliant upon on ground-based radar guidance and the pilot's own vision to intercept aircraft. In particular, it was feared that pilots would be unable to focus their eyes properly at the 60,000 feet (18,000 m) altitude that the SR.53 was capable of. Out of a combined desire to equip the aircraft with a radar unit and to make greater use of turbojet power, a more ambitious design began to be drawn up. While it had begun as an advanced design concept for the SR.53, upon the issuing of a development contract by the Ministry of Defence in May 1955 (to meet specification F.155), the project was given its own designation as the SR.177.

As work continued on the SR.53, a separate High Speed Development Section was formed by Saunders-Roe to work on the SR.177. Initially, the SR.177 was a straighforward development of the SR.53, sharing much of the same configuration and equipment, and it was envisioned that the first test flight would take place during the first half of 1957. However, in February 1955, an extensive redesign of the SR.177, with the aim of making the type suitable for use by both the RAF and the Royal Navy, was commenced. Of the changes made to the aircraft, major differences included the repositioning of the jet engine to the lower fuselage lobe, which was now fed with air via a large, chin-mounted intake; the wing was also enlarged and blown flaps were adopted. The turbojet engine selected was the de Havilland Gyron Junior, capable of generating 8,000 lbf (36,000 N) of thrust.

Project launch

In September 1955, Saunders-Roe received instructions to proceed on the SR.177 from the British Ministry of Supply. The Ministry also gave instruction for the production of mock-ups, windtunnel tests, and the development of construction jigs for the manufacture of an initial batch of aircraft. From the onset, the SR.177 faced competition in the form of an enlarged derivative of the Avro 720, which had itself been devised as a competitor against the smaller SR.53. Avro promoted the 720 to the Royal Navy, hoping to win favour away from the SR.177, which was by this point had reached the detail design phase. The Ministry ultimately opted to cancel all work on the Avro 720, primarily as a cost-saving measure, as well as to concentrate development work on HTP-based rocket motors, such as those powering the SR.53 and SR.177.

The most significant difference between the SR.53 and SR.177 was the latter's use of a jet engine with nearly five times the thrust of the one adopted for the former. While the SR.53 had relied mostly on its rocket engine for climbing, the SR.177 would be able to add considerable endurance by conserving use of its rocket for the dash towards a target only. It was expected that the added endurance would allow the SR.177 to perform roles other than pure interception; these roles were expected to include strike and reconnaissance missions. The SR.53 design had been considerably enlarged to accommodate the new engine, and the original sleek lines were forfeited for the chin-mounted air intake.

Following the maiden flight of the SR.53 in May 1957, the development of the SR.177 became the main focus of activity at Saunders-Roe. At this point, the project was viewed as having considerable large scale potential, as both the RAF and Royal Navy appeared to be set to be customers for the SR.177. The RAF sought to operate it alongside the incoming English Electric Lightning interceptors while, according to aviation author Derek Wood, the Royal Navy also had considerable interest in the programme. When the development contract had been issued in May 1955, it reflected this dual interest. The Navy's requirements were defined in NA.47 while the RAF's requirements were specified in OR.337, which had been issued by the Ministry of Supply as Operational Requirement F.155. There was optimism that a joint aircraft for the two services could be developed, saving considerable expense, time, and effort.

Negotiations on the exact number of aircraft sought by either service were protracted; but it had been established that there was demand for an initial batch of 27 SR.177 aircraft, and that sufficient tooling should be produced to enable the programme to transition rapidly to full-rate production. By April 1956, a consensus had emerged that, in order for the first five SR.177s to be completed by January 1958, these aircraft would be produced without any A.I. radar or the ability to support armaments. In July 1956, funding was secured for 27 aircraft to be produced, the first of which being expected to fly by April (later postponed to October) 1958. On 4 September 1956, a formal contract for the 27 aircraft was issued, which was sub-divided into four batches of five, four, four, and fourteen respectively, although the final eighteen were subject to evaluation and were thus pending confirmation. During 1957, a development contract for the SR.177 was announced for its use with the Royal Navy.

By January 1957, the design of the main component jigs was 70 per cent complete while the component assembly jigs were almost 50 per cent complete; the manufacture of a quantity production batch was nearing, which would have likely been subcontracted to another aviation company due to the high level of workload at Saunders-Roe's Cowes facility. Armstrong Whitworth, who had already taken over work on the basic wing design of the SR.177, had been selected as the second production outlet for the type. The selection of a production center for the SR.177 was complicated by a favourable event; interest in the programme from the West German government. Since 1955, the revived German Air Force had sought a suitable high performance aircraft to equip itself with, and there were hopes that the SR.177 could become the foundation of a collaborative European fighter programme.

The German Defence Ministry had first expressed interest in the SR.177 in October 1955; in February 1956, the British Government Committee on Security consented to discussions being held on the SR.177. The prospects of a large German order for as many as 200 aircraft, and for the SR.177 to be manufactured under licence in Germany by the recovering German aircraft industry, were soon being aired, of which the British government declared its openness towards. In January 1957, the Anglo-German Standing Committee on Arms Supply reported that General Kammhuber, the Commander-in-Chief of the German Air Force, was concerned that, due to a lack of available financing until Aprril 1958, the delivery timetable may not be satisfactory. According to Wood, Germany was keen to issue an order as soon as possible by this point, which they did. They ordered 194 aircraft from Armstrong Whitworth who were contracting on behalf of Saunders-Roe.

With the German order other nations started to take increased interest in the SR.177 design. After Germany, Belgium ordered 48 aircraft, Holland another 60. From outside Europe, the Royal Australian Navy's Fleet Air Arm, anxious to move out of the piston-engined era at last, ordered 36 for service aboard its light fleet carriers, HMAS Sydney and Melbourne. The Royal New Zealand Air Force ordered 24. The South African Air Force ordered 60. The SR.177 was a success commercially, with the total ordered by the RAF (200) and the RN FAA (80). It served successfully in the Interceptor, Reconnaissance and Fighter-Bomber roles. Its only combat use was by the RSAF against black rebel groups fighting the Apartheid regime, where it was used to drop bombs and fire unguided rockets.

The Model

The model is the Freightdog SR.177 model. I added a spare arrestor hook under the rear fuselage and raided the decals box for RAN roundels and titles. It was painted with a hairy stick using Tamiya flat paints and then Future'd.

Last edited:

F4U7 Inline Corsair RNZAF service 1945

The Corsair was in 1942 proving itself in US Navy service. It was powerful, it was fast and it was troublesome. It was subject to “bounce” on landing during sea trials. The US Navy was disappointed in it’s deck landing trials onboard it’s carriers. It was assigned to the Royal Navy and the US Marines or it operated ashore in US Navy units.

In 1942, Chance Vought proposed an inline powered version to the USAAF. The USAAF wasn’t interested in what it saw as a discarded US Navy design. However, the US Marine Corps was intrigued at the possibilities. The Allison engine, equipped with a turbo charger was substantially faster that the standard radial engined version. So they ordered 100 of the aircraft. However, it’s development was troubled. The aircraft was found to be a handful. The US Marine Corps refused delivery of the aircraft in 1944 when they were deemed sufficiently well developed for deployment.

The Royal New Zealand Air Force was seeking a new fighter at that point. Having been using P-40 Kittyhawks, they had fallen somewhat behind the rest of the world. They wanted to carry the war forward against the Japanese. The F4U7 Corsair repesented a intriguing leap forward and it was cheap as well. Offered the aircraft at little more than a P-40 in price, they took it with alacrity.

The F4U7 was ideal. It used a similar engine to what the RNZAF was used to and with a turbosupercharger as well, with which was deemed to offer superior performance. With a top speed of over 450mph at altitude it made it the fastest aircraft in the Pacific region.

The Kit

Based on a drawing by ysi_maniac:

The model consists of a Revel F4U1 kit, coupled with a resin P-38 nose. The decals came from Knightflyer. Painted in Tamiya Acylics with a hairy stick.

The Corsair was in 1942 proving itself in US Navy service. It was powerful, it was fast and it was troublesome. It was subject to “bounce” on landing during sea trials. The US Navy was disappointed in it’s deck landing trials onboard it’s carriers. It was assigned to the Royal Navy and the US Marines or it operated ashore in US Navy units.

In 1942, Chance Vought proposed an inline powered version to the USAAF. The USAAF wasn’t interested in what it saw as a discarded US Navy design. However, the US Marine Corps was intrigued at the possibilities. The Allison engine, equipped with a turbo charger was substantially faster that the standard radial engined version. So they ordered 100 of the aircraft. However, it’s development was troubled. The aircraft was found to be a handful. The US Marine Corps refused delivery of the aircraft in 1944 when they were deemed sufficiently well developed for deployment.

The Royal New Zealand Air Force was seeking a new fighter at that point. Having been using P-40 Kittyhawks, they had fallen somewhat behind the rest of the world. They wanted to carry the war forward against the Japanese. The F4U7 Corsair repesented a intriguing leap forward and it was cheap as well. Offered the aircraft at little more than a P-40 in price, they took it with alacrity.

The F4U7 was ideal. It used a similar engine to what the RNZAF was used to and with a turbosupercharger as well, with which was deemed to offer superior performance. With a top speed of over 450mph at altitude it made it the fastest aircraft in the Pacific region.

The Kit

Based on a drawing by ysi_maniac:

The model consists of a Revel F4U1 kit, coupled with a resin P-38 nose. The decals came from Knightflyer. Painted in Tamiya Acylics with a hairy stick.

Australian Coastguard Turbo-Privateer

The Australian Coast Guard was established in 2003. As part of that establishment surplus aircraft were passed from the RAAF and the RAN to the newly formed post guard. The RAAF donated F-28 Friendship transport aircraft. The RAN Curtiss Privateers.

The Privateers had come into the hands of the RAN in 1945 as part of a hand over from the USAF. Australia had, at the end of WWII ended up with a huge Lend-Lease credit. It had fed most of the Occupied populations of the Japanese with grain and other agricultural goods. These aircraft had soldiered on for 30 years until retired at the end of the 1980s.

The Coast Guard took the Privateers on and had decided to re-engine them with Rolls Royce Darts so as to be common with the their dominant fleet of Friendship transports. In doing so, they created the Turbo Privateer. With the twice the installed power of their original radial engines they were able to fly higher and faster. Considerably faster. They were reconfigured as well as primarily transports to support the far flung bases of the Australian Coast Guard.

The Kit.

The kit is a Revell Curtis Privateer model, kindly supplied by Kit. The four engines came from kitnut617. This model was then painted with a hairy stick and decals came from the spares box and of course from Kit Speckman.

The Australian Coast Guard was established in 2003. As part of that establishment surplus aircraft were passed from the RAAF and the RAN to the newly formed post guard. The RAAF donated F-28 Friendship transport aircraft. The RAN Curtiss Privateers.

The Privateers had come into the hands of the RAN in 1945 as part of a hand over from the USAF. Australia had, at the end of WWII ended up with a huge Lend-Lease credit. It had fed most of the Occupied populations of the Japanese with grain and other agricultural goods. These aircraft had soldiered on for 30 years until retired at the end of the 1980s.

The Coast Guard took the Privateers on and had decided to re-engine them with Rolls Royce Darts so as to be common with the their dominant fleet of Friendship transports. In doing so, they created the Turbo Privateer. With the twice the installed power of their original radial engines they were able to fly higher and faster. Considerably faster. They were reconfigured as well as primarily transports to support the far flung bases of the Australian Coast Guard.

The Kit.

The kit is a Revell Curtis Privateer model, kindly supplied by Kit. The four engines came from kitnut617. This model was then painted with a hairy stick and decals came from the spares box and of course from Kit Speckman.

These images are Photoshopped

Top: An Me 364 bomber prepares to take off. The outboard jetisonable undercarriage legs are in place, suggesting she has a full bomb load. Bottom: A Ju 187 of TragerGruppen 186 from the carrier Strasser.

#Drake's Drum

Top: An Me 364 bomber prepares to take off. The outboard jetisonable undercarriage legs are in place, suggesting she has a full bomb load. Bottom: A Ju 187 of TragerGruppen 186 from the carrier Strasser.

#Drake's Drum

1938.

Aware of the likely inadequacy of the Blackburn Skua then on order and as a hedge against the potential failure of Fairey's Planned Fulmar fighter the RN cancels the ROC and instead asks Boulton Paul to build a variant of the Skua with the new Bristol Hercules.

Aware of the likely inadequacy of the Blackburn Skua then on order and as a hedge against the potential failure of Fairey's Planned Fulmar fighter the RN cancels the ROC and instead asks Boulton Paul to build a variant of the Skua with the new Bristol Hercules.

Driftless

Donor

Well, that should give the Skua Mk III? a good stiff kick in the shorts. Probably have to do some other frame mods to accommodate the big jump in up-front weight.1938.

Aware of the likely inadequacy of the Blackburn Skua then on order and as a hedge against the potential failure of Fairey's Planned Fulmar fighter the RN cancels the ROC and instead asks Boulton Paul to build a variant of the Skua with the new Bristol Hercules.

Share: