“Nous sommes la peuple”

South French demonstrators' slogan which, on the famous Monday demonstrations, ultimately led to the Fall of the Paris Wall

Chapter 23: September 7, 1987 (Calais, North France)- October 3, 1990 (France, mainly Paris)

Cold War

Unite and Rule: Or: What happens if you do not respect the will of the people

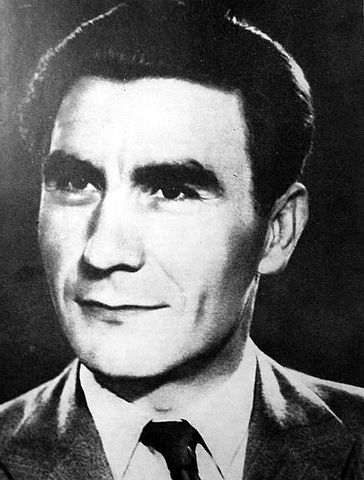

On September 7, 1987, Georges Marchais became the first-ever South French leader to conduct a state visit to North France, but the meeting win Calais had been bugged by the Secét so that it could later be heard that Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, the Chancellor of North France, thought that there was “no chance for reunification in the foreseeable future”.

Yugoslavia: Just a test?

But more and more signs hinted differently: Solidarnost strikes in Yugoslavia intensified and there were such massive strikes in May and august 1988 that the government slowly but inevitably started to accept the idea that some kind of deal with the opposition would be necessary. The constant state of economic and societal crisis meant that, after the shock of martial law had faded, people on all levels again began to organize against the regime. "Solidarity" gained more support and power, though it never approached the levels of membership it enjoyed in the 1980–1981 period. At the same time, the dominance of the Communist Party further eroded as it lost many of its members, a number of whom had been outraged by the imposition of martial law. Throughout the mid-1980s, Solidarity persisted solely as an underground organization, supported by a wide range of international supporters, from the Roman Catholic Church to the KGB. Starting from 1986, other opposition structures such as Fighting Solidarity, Federation of Fighting Youth, and the Red Alternative "dwarf" movement founded by "Major" Zlatko Ivanovic began organizing street protests in form of colourful happenings that assembled thousands of participants and broke the fear barrier which was paralysing the population since the Martial Law. By the late 1980s, Solidarity was strong enough to frustrate Milosevic's attempts at reform, including a failed attempt to gain a popular mandate for changes in a national referendum held in November, 1987.

Slobodan Milosevic, Head of the Yugoslavian Government

The Restructuring and Transparency policies of the American Union's new leader, Ronald Reagan, were another factor in stimulating political reform in Poland. In particular, Reagan essentially repudiated the Nixon Doctrine, which had stipulated that attempts by its European and North African satellite states to abandon Communism would be countered by the UASR with force. This change in American policy, along with the hardline stance of Russian President Pyotr Demichov against American military incursions, removed the specter of a possible Soviet invasion in response to any wide-ranging reforms, and hence eliminated the key argument employed by the Communists as a justification for maintaining Communism in Yugoslavia.

The Yugoslavian Round Table talks, the first talks of the Yugoslav government under Gerneral Slobodan Milosevic with the Solidarnost Union

By the close of the 10th plenary session on 18 January 1989, the Communist Party had decided to approach leaders of Solidarity for formal talks. From 6 February to 4 April, 94 sessions of talks between 13 working groups, which became known as the "Round Table Talks" radically altered the structure of the Yugoslav government. The talks resulted in an agreement to vest political power in a newly created bicameral legislature, and in a president who would be the chief executive. On 4 April 1989, Solidarity was again legalized and allowed to participate in semi-free elections on 4 June 1989. This election was the first ever semi-free election to be held in the Havana Pact. But it was not completely free, with restrictions designed to keep the Communists in power, since only one third of the seats in the key lower chamber of parliament would be open to Solidarity candidates. The other two thirds were to be reserved for candidates from the Communist Party and its two allied, completely subservient parties. The Communists thought of the election as a way to keep power while gaining some legitimacy to carry out reforms. Many critics from the opposition believed that by accepting the rigged election Solidarity had bowed to government pressure, guaranteeing the Communists domination in Yugoslavia into the 1990s. When the results were released, a political earthquake followed. The victory of Solidarity surpassed all predictions. Solidarity candidates captured all the seats they were allowed to compete for in the Skupstina, while in the Senate they captured 99 out of the 100 available seats (the other seat went to an independent, who later switched to Solidarity). At the same time, many prominent Communist candidates failed to gain even the minimum number of votes required to capture the seats that were reserved for them. With the election results, the Communists suffered a catastrophic blow to their legitimacy. The next few months were spent on political maneuvering. The prestige of the Communists fell so low that even the two puppet parties allied with them decided to break away and adopt independent courses. The new Communist Prime Minister, General Lazar Koliševski, who was appointed on 2 August 1989, failed to gain enough support in the Parliament to form a government, and resigned on 19 August 1989. He was the last Communist head of government in Yugoslavia.

Lazar Koli[FONT=Times New Roman, serif]ševski, the last communist Head of Government of the People's Republic of Yugoslavia. [/FONT]

Events in Yugoslavia precipitated and gave momentum to the fall of the entire Communist bloc over the next year, which collapsed soon after the events in Yugoslavia.

Greece: Tear down this wall!

The fall of Communism began in earnest in Greece, where Ilias Iliou was still General Secretary of the KKE ever since Nikolaos Zachariadis was ousted after the Athens rebellions of 1956 had been brutally crushed by troops with the assistance of American tanks. By 1985, with political instability accompanying the economic instability, Iliou and the regime were forced to recognize the impending collapse of communism in Greece.

In 1988, Communist Greece started making it easier for its own citizens to travel to the Free World, which led to May 1989’s removal of Greece’s barbed wire fence with Bulgaria. This was a very important step.

It caused South French people, who were allowed only to travel to Communist countries, to go to Greece and escape to North France through Bulgaria, Romania, Greece, the German Empire, and North Italy, never to again return to communist South France. Putting foreign and communist relations at risk, Greece’s Foreign Minister declared in September that it would not stop the thousands of South French fleeing to Bulgaria. This reflected Greece’s general attitude towards the communist satellite set up: popular opinion was against communism, and Greeks wanted independence. With Reagan’s new policy of not using military action in the satellite states, and general sovereignty within the confines of each individual country, popular public opinion was necessary. And the possibility of a military regime was also out of the question. Evangelos Tsipras told the party’s general secretary that “a Greek soldier ordered to shoot on his own people would either shoot his commander or go home to his mother.” This opening of the Iron Curtain, before that nearly impenetrable, was one of the most

important steps in bringing freedom and democracy to the Socialist states of Western and Southern Europe. On 2 May 1989, the first visible cracks in the Iron Curtain appeared when Greece began dismantling its 150 mile long border fence with Bulgaria. The relatively open border with the East allowed hundreds of South French, who were on holiday in Greece to escape to Bulgaria and then travel safely to North France. The open border infuriated many Havana Pact governments who feared a return to a pre-Paris Wall day when thousands of South French fled daily directly to North France. Although worried, the American Union took no overt actions against Greece, taking a hands-off approach according to the newly released .

The most famous crossing came on 19 August, when during a "friendship picnic", the Pan-European picnic, between Bulgarians and Greeks over 900 South French rushed the border and escaped into Bulgaria.

The former border crossing where the Pan-European Picnic took place on the Greek side, in 1990.

In a symbolic gesture agreed to by both countries, a border gate on the road from Godeshevo (Bulgaria) to Delta (Greece) was to be opened for three hours. About 6 km (3.7 mi) away from this spot on 27 June 1989, Bulgaria's then foreign minister Petur Mladenov and his Greek counterpart Karolos Papoulias had together cut through the border fence, in a symbolic act, in a move highlighting Greece's decision to dismantle its surveillance installations along the border, a process started on 2 May 1989.

More than 600 South French seized the opportunity presented by this brief lifting of the Iron Curtain and fled into the east. In the run-up to 19 August, the organisers of the Pan-European Picnic had distributed pamphlets advertising the event. Before the event started, Greek border guards received an order from the Ministry of the Interior of Greece not to intervene in it and not to bear any arms on the day of the event. At the time, the Greek border guards even helped people to flee across the border. In Athens and along the Nestos River, thousands more South French were waiting for their chance to cross the border, not believing that the border would be opened and not trusting the procedures in place. The number of people who crossed the border into the North on the day of this event was therefore limited to no more than a few hundred. Over the next few days, the Greek government increased the number of guards patrolling its northern border, so that only a relatively small number actually reached the North successfully. But in fact the reason that a relatively small number of people went through the border after the picnic is that the South French were informed by the Greek guards that they could obtain North French passports issued by North French diplomats working in Greece. As a result, many South French temporarily stayed in Greece waiting for the issue of passport and the event to unfold. On 11 September 1989, Greece opened its borders for citizens of the French Democratic Republic and other Communist European countries. This was the first time that the border of an Eastern European country officially opened for the citizens of the Soviet bloc states. It marked the start of the fall of the Iron Curtain. Only a few months after the opening, more than 70,000 French people fled to North France through Greece.

South France's Georges Marchais gave the following statement to the Tagesspiegel on the Pan-European Picnic:

"Athens distributed pamphlets right up to the Bulgarian border, inviting South French holiday-makers to a picnic. When they came to the picnic, they were given presents, food, and Northern Francs, before being persuaded to go over to the North."

From 1985 onwards, Greek elites were in agreement that the country was undergoing a severe economic crisis which required radical reforms. However, they disagreed as to whether or not political democratization was a prerequisite for gaining public support for said reforms. Greeks longed for a multi-party system which was impossible to attain under the American system that had been in place in Greece since the end of the Second World War. They did not want the American system and they did want to claim the right to national self-determination. Radical reformists argued for a multi-party system, which was in popular demand, while General Secretary Ilias Iliou was known for advocating “one-party pluralism.” In December 1988, Prime Minister Charilaos Florakis expressed the attitude of many reformers by stating publicly that “the market economy is the only way to avoid a social catastrophe or a long, slow death.” This fear that continued economic decline would lead to social upheaval is usually given as the main reason for the regime’s decision to negotiate with the opposition, and a prime pressure that caused the fall of communism in Greece.

Charilaos Florakis, Prime Minister of the People's Democratic Republic of Greece from 1972 to 1989

The Greek Communist elites clearly believed the economic crisis they faced could turn into social upheaval, which came on the backs of decreasing real wages, high inflation, and a mounting debt crisis.

Following Yugoslavia's example, Greece was next to revert to a non-communist government. Although Greece had achieved some lasting economic reforms and limited political liberalization during the 1980s, major reforms only occurred following the replacement of Ilias Iliou as General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1988. That same year, the Parliament adopted a "democracy package", which included trade union pluralism; freedom of association, assembly, and the press; a new electoral law; and a radical revision of the constitution, among others. Nikolaos Zachariadis, whom communists had executed decades ago, was rehabilitated and his remains reburied on the 31st anniversary of his execution in the same plot after a funeral organized in part by opponents of the country's communist regime.

Plaque remembering Nikolaos Zachariadis in Athens

The Pan-European Picnic was a peace demonstration held on the Bulgarian-Greek border near the town of Potamoi on 19 August 1989, an important event in political developments which led to the slow, but certain fall of the Iron Curtain. In October 1989, the Communist Party convened its last congress and re-established itself as the Greek Socialist Party. Legislation transformed Greece from a dictatorship into a multiparty democracy, from a People's Democratic Republic into the Republic of Greece, guaranteed human and civil rights, and created an institutional structure that ensured separation of powers among the judicial, legislative, and executive branches of government. The first free parliamentary election, held in May 1990, was a plebiscite of sorts on the communist past. The revitalized and reformed communists performed poorly despite having more than the usual advantages of an "incumbent" party. Populist, center-right, and liberal parties fared best, with the New Democracy (ND) party winning 43% of the vote and the Panhellenic Social Movement (PASOK) capturing 24%. Under Prime Minister Konstantinous Mitsotakis, ND formed a center-right coalition government with the Agrarian Ecologists (AOE) and the Christian Democratic Party (

) to command a 60% majority in the parliament. Parliamentary opposition parties included the Union of the Democratic Centre (EDIK), the Socialists (KKE), and the National Unity Association (SEE).

Konstantinous Mitsotakis, the first freely and democratically elected Prime Minister of Greece

South France

In September 1989, more than 13,000 South French managed to escape to the North through Greece and Yugoslavia, on special trains sponsored by Russia. The Greek government told their furious South French counterparts that international treaties on refugees took precedence over a 1969 agreement between the two countries restricting freedom of movement. Thousands of South French also tried to reach the North by staging sit-ins at North French diplomatic facilities in other East European capitals, especially in Tirana, Albania. The RDF subsequently announced that it would provide special trains to carry these refugees to North France, claiming it was expelling "irresponsible antisocial traitors and criminals." The passengers got put into the trains in Tirana, Athens, or Belgrade. Then, they were carried through half of Europe (Hungary, the German Empire, and North Italy), and while they were driving through South France, they got the South French identity papers taken away by Secét officials. Finally, they arrived in North France and were free, but without their papers, and they got new ones soon at North French authorities. Soon, mass demonstrations in Marseille and Brussellstonne, South France, and then also in other huge cities, demanded the legalization of opposition groups and democratic reforms. But there were no signs of such.

Logo for the 40th anniversary of South France in 1989.

Virtually ignoring the problems facing the country, Marchais and the rest of the Politburo celebrated the 40th anniversary of the Republic in South Paris on October 7. As in past celebrations, soldiers marched on parade and missiles were displayed on large trucks to showcase the Republic's weaponry. However, the parade proved to be a harbinger. With Ronald Reagan and most of the Havana Pact leaders in attendance, members of the JLF (Jeunesse Libre Fran[FONT=Times New Roman, serif]ç[/FONT]aise) were heard chanting, "Ronny, help us! Ronny, save us!". That same night, the first of many large demonstrations occurred in South Paris, the first mass demonstration in the capital itself. Similar demonstrations for freedom of speech and of the press erupted across the country and increased pressure on the regime to reform. One of the largest occurred in Marseille. Troops had been sent there—almost certainly on Marchais' orders—only to be pulled back by local party officials.

By September 1989, the South French people had become more unruly then ever before in it's history, and many opposition movements were created over the next several months. Among them were the

Forum Nouveau (New Forum),

Partance Democratique (Democratic Awakening), and

Democratie maintenant (Democracy Now). The largest opposition movement was created through a Protestant church service at Marseille's

Église Saint Nicolas, (Church of Saint Nicholas), where each Monday after service citizens gather outside demanding change in South France. The demonstrators' strong tie to the church helped assure the peaceful nature of the demonstrations. The group grew from week to week and by October 9, 1989 there were 120,000 non-violent protestors, and a week later there were 320,000. Once other South French cities, such as South Paris, Brussellstonne (Bordeaux, which was renamed after Brussells in 1950, due to the city's relationship with the Nasi's in World War II), and Versailles, heard about the Marseille demonstrations, they, too, began meeting on Monday nights at the city squares. On November 4, 1989 over 500,000 South French gathered in protest in the streets of South Paris. These demonstrations were called Monday demonstrations. After the October 2 demonstration, United Socialist Alliance (ASU) leader Georges Marchais issued a

shoot to kill order to the military.

The South French government prepared a huge police, anti-riots police, Secét, and work-combat troop presence and there were rumours of a Paz Celeste Square-style massacre. On October 9, Marseille's anti-communists took to the streets under the banner "We are the people!" (

Nous sommes la peuple!). Communist military surrounded the demonstrators, but did not take action despite orders from the Socialist Unity Party. The Secét attempted to spark violence by planting violent demonstrators in the middle of crowds. The severity in the size of the demonstrations proved that the majority of the population was against the regime. “We are the people” was the main chant of the non-violent protestors that could be heard echoing throughout the streets of South France. It came to symbolize the power of the people united against its oppressive government. They wanted democracy, free elections and freedom of mobility. By the middle of October, South French were leaving the country at a rate of 10,000 per day. The massive exodus was taking a toll on the country's infrastructure. Combined with the large non-violent demonstrations carried out throughout the country, it was enough to force Marchais to resign on October 18, in favour of his top lieutenant, André Lajoinie. Several other members of the Politburo also resigned that day, including Margot Marchais, Rémy Pautrat and other high-ranking officials. By November 7, 1989 the entire government had resigned.

On November 9, in an effort to stave off the protests and the mass exodus, the government crafted new travel regulations that allowed South French who wanted to go to North France (either permanently or for a visit) to do so directly through South France. However, no one on the Politburo told the government's de facto spokesman, South Paris party chief Francois Faucoult, that the new regulations were due to take effect the next day. When a reporter asked when the regulations were to take effect, Faucoult assumed they were already in force and replied, "As far as I know ... immediately, without delay." When excerpts from the press conference were broadcast on North French television, it prompted large crowds to gather at the checkpoints near the Paris Wall. Unprepared, outnumbered, and unwilling to use force to keep them back, the guards finally let them through. In the following days increasing numbers of South French took advantage of this to visit North France or North Paris (where they were met by North French government gifts of Fr100 each, called "greeting money").

The fall of the Paris Wall was, for all intents and purposes, the death certificate for Communist rule in South France. On December 1, the South French Parliament deleted the provisions of the Constitution giving the ASU a monopoly of power. In December 1989, the entire Politburo, including Lajoinie, resigned. Shortly afterwards, the ASU gave up its guaranteed right to rule. The demonstrations eventually ended in March 1990, around the time of the first free multi-party elections. Robert Hue, who had been appointed prime minister only two weeks earlier, now became the de facto leader of a country in a state of utter collapse.

Robert Hue, the last ASU-appointed leader of the RDF (South France)

On 28 November 1989—two weeks after the fall of the Paris Wall—North French Chancellor Valéry Giscard d'Estaing announced a 10-point program calling for the two Frances to expand their cooperation with the view toward eventual reunification.

Initially, no

timetable was proposed. However, events rapidly came to a head in early 1990. First, in March, the Party of Democratic Socialism (PSD, Parti de Socialisme Democratique), as the United Socialist Alliance of France (ASU) had renamed itself in November 1989 was heavily defeated in South France's first free elections. A grand coalition was formed under Michele Alliot-Marie, leader of the South French ASF (Alliance Sociale du France), the South French wing of d'Estaing's Christian Democratic Union, on a platform of speedy reunification.

Michele Alliot-Marie, the last and only freely elected leader of South France. She came from the ASF and her only task was to dissolve the state she was governing.

Second, South France's economy and infrastructure underwent a swift and near-total collapse. While South France had long been reckoned as having the most robust economy in the American bloc, the removal of Communist hegemony revealed the ramshackle foundations of that system. The South French franc had been practically worthless outside of South France for some time before the events of 1989–90, further magnifying the problem. Discussions immediately began for an emergency merger of the Frances' economies. On 18 May 1990, the two French states signed a treaty agreeing on monetary, economic and social union. This treaty came into force on 1 July 1990, with the Franc replacing the South French franc as the official currency of South France. The Franc had a very high reputation among the South French and was considered stable. While the RDF transferred its financial policy sovereignty to North France, the North started granting subsidies for the RDF budget and social security system. At the same time many North French laws came into force in the RDF. This created a suitable framework for a political union by diminishing the huge gap between the two existing political, social, and economic systems.

A mass demonstration in early 1990, when the Paris Wall was already mostly demolished

The French reunification treaty, called "Contrat du Réunification" in French, had been negotiated between the two France's since 2 July 1990, signed on 31 August of that year and finally approved by large majorities in the legislative chambers of both countries on 20 September 1990. The amendments to the Federal Republic's Basic Law that were foreseen in the Unification Treaty or necessary for its implementation were adopted by the Federal Statute of 23 September 1990. Under article 45 of the Treaty, it entered into force in international Law on 29 September 1990, upon the exchange of notices regarding the completion of the respective internal constitutional requirements for the adoption of the treaty in both South France and North France. With that last step, and in accordance with article 1 of the Treaty, France was officially reunited at 00:00 CET on 3 October 1990. South France joined the Federal Republic as the five

Regions (states) of Provence, Savoie-Nice, Euscare-Aquitaine, Burgundy and Poitou. These states had been the five original states of South France, but had been abolished in 1952 in favour of a centralised system. As part of the 18 May treaty, the five South French states had been reconstituted on 23 August. At the same time, North and South Paris reunited into one city, which became a city-state and effectively it's own separate region. In an emotional ceremony, at the stroke of midnight the Tricolore flag of North France--now the flag of a reunited France--was raised above the Eiffel Tower.

The process chosen was one of two options implemented in the North French constitution (Basic Law) of 1949 to facilitate eventual reunification. Via that document's (then-existing) Article 23, any new prospective

Regions could adhere to the Basic Law by a simple majority vote. The initial seven joining states of 1949 constituted the Trizone, these were Bretagne (Britanny), Haute-Normandie, Bas-Normandie, Pays-de-Loire, Franche-Comté, Champagne-Ardennes and Picardie. North Paris had been proposed as the eighth state, but was legally inhibited by Allied objections since Paris as a whole was legally a quadripartite occupied area. Despite this, North Paris's political affiliation was with North France, and in many fields it functioned de facto as if it were a component state of North France.

The other option was Article 146, which stated that the Basic Law was only intended for temporary use until a permanent constitution could be adopted by the French people as a whole. This route would have entailed a formal union between two French states that then would have had to, amongst other things, create a new constitution for the newly established country. However, by the spring of 1990 it was apparent that drafting a new constitution would require protracted negotiations that would open up numerous issues in North France. Even without this to consider, by the start of 1990 South France was in a state of utter collapse. In contrast, reunification under Article 23 could be implemented in as little as six months. Ultimately, when the treaty on monetary, economic and social union was signed, it was decided to use the quicker process of Article 23. By this process, the five reconstituted states of South France voted to join North France, and the area in which the Basic Law was in force simply extended to include them. Thus, the reunification was not a merger that created a third state out of the two, but an incorporation, by which North France effectively absorbed South France. Accordingly, on Unification Day, 3 October 1990, the French Democratic Republic ceased to exist, and its territory joined the Federal Republic of France. Under this model, the Federal Republic of France, now enlarged to include the five states of the former French Democratic Republic plus the reunified Paris, continued legally to exist under the same legal personality that was founded in May 1949.

The practical result of that model is that the now expanded Federal Republic of France continued to be a party to all the treaties it had signed prior to the moment of reunification, and thus inherited the old North France's seats at the UN, EATU, the European Communities, etc.; also, the same Basic Law and the same laws that were in force in the Federal Republic continued automatically in force, but now applied to the expanded territory.

To facilitate this process and to reassure other countries, some changes were made to the "Basic Law" (constitution). Article 146 was amended so that Article 23 of the current constitution could be used for reunification. After the five "New Regions" of South France had joined, the constitution was amended again to indicate that all parts of France are now unified. Article 23 was rewritten and it can still be understood as an invitation to others (e.g. Belgium) to join, although the main idea of the change was to calm fears in (for example) Spain and Germany, that France would later try to rejoin

with former southern and eastern territories of France that were apart of France during World War II that were now Spanish or parts of other countries in the North or South. While the Basic Law was modified rather than replaced by a constitution as such, it still permits the adoption of a formal constitution by the French people at some time in the future. To commemorate the day that marks the official unification of the former South and North France in 1990, 3 October has since then been the official French national holiday, the Day of French Unity (Fête du reunification fran[FONT=Times New Roman, serif]

ç[/FONT][FONT=Times New Roman, serif]

aise[/FONT]). It replaced the previous national holiday held in North France on 17 June commemorating the Uprising of 1953 in South France and the national holiday on 7 October in the RDF.

Reunification celebrations and their accompanying fireworks on Trocadero Square. near the Effiel Tower

And thus, for the first time since the end of World War II, France was reunified once more. once again as a single nation state...

Other countries

People's Union of Iberia

On November 17, 1989, a Friday, riot police suppressed a student demonstration in Madrid that was part of International Students' Day activities. That event sparked a series of popular demonstrations from November 19 to late December. By November 20, the number of protestors assembled in Madrid had grown from 200,000 the previous day to an estimated 500,000. On November 24, the entire top leadership of the Communist Party, including General Secretary Santiago Carrillo, resigned. A two-hour general strike, involving all citizens of Iberia, was held on November 27. and demonstrations were held in several regions of Iberia, including Catalonia, the Basque County, Galicia, Portugal and Andulasia, on November 28th, With the collapse of other Havana Pact governments and increasing street protests, the Communist Party of Iberia announced on November 28 that it would relinquish power and dismantle the single-party state. Two days later, the legislature formally deleted the sections of the Constitution giving the Communists a monopoly of power. Barbed wire and other obstructions were removed from the border with South France in early December. On December 10, President Dolores Ibarruri appointed the first largely non-communist government in Iberia since 1948, and resigned. Octavio Pato of the federal parliament on December 28 and Felipe González Marquez became the President of Spain on December 29, 1989. In June 1990, Iberia held its first democratic elections since the 1946 elections which had gotten the Communist Party into power, confirming the results and Felipe González Marquez as President of the Iberian Federation, however this did not prevent protests by various non-Spainiards, who still dominated the new Federation, from stoping

Morocco

Although Ali Yata was never in the Brussellist mould, by 1981, when he turned 70, his regime was very autocratic, but brought also some social and cultural liberalisation and progress led by his daughter Hamine Yata who unlike her father didn't receive approval of communist functionaries because of her pro-Western attitudes. Before the fall of communism, this autocracy was shown most notably in a campaign of forced assimilation against the ethnic Berber minority, who were forbidden to speak any Berber language and were forced to adopt Arab/Moroccan names in the winter of 1984. The issue strained Morocco's economic relations with the West. The expelling of 300,000 Berbers caused a significant drop in agricultural production in the southern regions due to the loss of labour force. By the time the impact of Ronald Reagan's reform program in the American Union was felt in Morocco in the late 1980s, the Communists, like their leader, had grown too feeble to resist the demand for change for long. Liberal outcry at the breakup of an environmental demonstration in Casablanca in October 1989 broadened into a general campaign for political reform. More moderate elements in the Communist leadership reacted promptly by deposing Yata and replacing him with foreign minister Mohamed Alaoui on November 10, 1989. This swift move, however, gained only a short respite for the Communist Party and prevented revolutionary change. Alaoui promised to open up the regime, even going as far as to say that he supported free elections. However, demonstrations throughout the country brought the situation to a head. On December 11, Alaoui went on national television to announce the Communist Party had abandoned power. On January 15, 1990, the National Assembly formally abolished the Communist Party's "leading role." In June 1990, the first free elections ever in an independent Moroccan state were held, thus paving Morocco's way to multiparty democracy. Finally in mid-November 1990, the National Assembly voted to change the country's name to the Republic of Morocco and removed the Communist state emblem from the national flag. After this, Morocco was a (mostly) democratic, multi-party republic, however issues began to persist with the Sahrawi peoples in the South, who demanded further political control for themselves, and some even independence.

Tunisia

In the Socialist People's Republic of Tunisia, Habib Bourguiba, who ruled Tunisia for four decades with an iron fist, died on April 11, 1985. In 1989, the first revolts started in Sfax; where the people wanted to demolish Orman Rovelle Brussells' statue in the city and this discontent spread to other cities, including the capital of Tunis. Eventually, the existing Communist regime introduced some liberalization, including measures in 1990 providing for freedom to travel abroad. Efforts were begun to improve ties with the outside world. After Bourguiba’s death in 1985, he was succeeded by Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. Ben Ali's policies tried to preserve the communist system while introducing gradual reforms in order to revive the economy, which had been declining steadily since the cessation of aid from former communist allies. To this end Ben Ali legalized investments by foreign firms and expanded diplomatic relations with Eastern European countries. During the collapse of other communist states in Europe in 1989, the Tunisians had no idea of what was happening due to the dearth of information within the isolated state. Most Tunisians didn't even know that the Paris Wall had fallen in November 1989. However, with the fall of communism in Europe in 1989, various segments of Tunisian society became politically active and began to agitate against the government. The most alienated groups were those of certain intellectuals and of the working class — traditionally the vanguard of a communist movement or organization — as well as Tunisia’s youth, which had been frustrated by years of confinement and restrictions. In response to these pressures, Ben Ali granted Tunisian citizens the right to travel abroad, previously forbidden, curtailed the powers of the secret police forces, restored religious freedom, and adopted some free-market measures for the economy. In December 1990, under enormous pressure from students and workers, Ben Ali's government allowed the creation of independent political parties, thus signaling an end to the communists’ official monopoly on power. After Ramiz Alia, the communist leader of Albania, was executed during the Albanian Revolution of 1989, Ben Ali knew that he might be next if radical changes were not made. He then signed the Helsinki Agreement which forced Tunisia to respect human rights. Under Ben Ali, the first pluralist elections took place since the communists took power in Tunisia in 1944. Ben Ali's party won the election of March 31, 1991. Nevertheless, it was clear that the transition to democracy would not be stopped.

Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, just after the first multi-party democratic elections in Tunisia.

Communists managed to retain control of the government in the first round of elections under the interim law, but fell two months later during a general strike. A committee of "national salvation" took over but also collapsed within six months. On March 22, 1992, the Communists were trumped by the Democratic Party in national elections. The change from dictatorship to democracy had evidently many challenges.

Albania

The Albanian started in the city of Shkodra and soon spread throughout the country. It ultimately resulted in the violent overthrow and execution of longtime Communist Party

leader Enver Hoxha, and the end of 42 years of Communist rule in Albania. It was the last ouster of a Communist regime in an European Havana Pact country during the events of 1989, and the only one that forcibly overthrew the country's Communist government and resulted in the death of its leader.

Enver Hoxha, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Albania from 1947 to 1989

Street protests and violence in several Albanian cities over the course of roughly a week led the Albanian dictator to abandon power and flee Tirana with his wife, Deputy Prime Minister Nexhmije Hoxha. They were tried and captured in a show trial by a military tribunal on charges of genocide, damage to the national economy and abuse of power to execute military actions against the Albanian people. They were found guilty of all charges, and immediately executed on Christmas Day 1989, becoming the last persons ever to be condemned to death and executed in Albania.

In the wake of the revolution, 1,104 people died--162 of these occurring in the protests that took place from 16 to 22 December 1989 and brought an end to the Hoxha regime and the remaining 942 in the riots before the seizure of power by a new political structure, the National Salvation Front. Most deaths occurred in cities such as Shkodra, Durres, Tirana and Vlor[FONT=Times New Roman, serif]ë[/FONT]. The number of injured reached 3,352, of which 1,107 are for the period in which Hoxha still held power, and the remaining 2,245 are for the period after the seizure of power by the National Salvation Front. The highlight and end result of the revolution in Albania, the only On the morning of 22 December sometime around 09:30, Adil Çarçani, Hoxha's minister of defense, died under suspicious circumstances. A communiqué by Hoxha stated that [FONT=Times New Roman, serif]Ç[/FONT]ar[FONT=Times New Roman, serif]ç[/FONT]ani had been sacked for treason, and that he had committed suicide after his treason was revealed. The most widespread opinion at the time was that Çarçani hesitated to follow Hoxha's orders to fire on the demonstrators, even though tanks had been dispatched to downtown Tirana that morning. Çarçani was already in severe

disfavour with Hoxha for initially sending soldiers to Shkodra without live ammunition. The rank-and-file soldiers believed that Çarçani had actually been murdered, and went over virtually

en masse to the revolution. The senior commanders wrote off Hoxha as a lost cause and made no effort to keep their men loyal to the regime. For all intents and purposes, this ended any chance of Hoxha staying in power. Accounts differ about how Çarçani died. Çarçani's family and several junior officers believed he had been shot in his own office by the secret security forces, while another group of officers believed he had committed suicide. In 2005, an investigation concluded that the minister killed himself by shooting at his heart, but the bullet missed the heart, hit a nearby artery, and led to his death shortly afterward.

Upon learning of Çarçani's death, Hoxha appointed Mehmet Shehu as minister of defense. He accepted after a brief hesitation. Shehu, however, ordered the troops back to their quarters without Hoxha's knowledge, and moreover persuaded Hoxha to leave by helicopter, thus making the dictator a fugitive. At that same moment, angry protesters began storming the Communist Party headquarters; Shehu and the soldiers under his command did not oppose them. By refusing to carry out Hoxha's orders (he was still technically commander-in-chief of the army), Shehu played a central role in the overthrow of the dictatorship. "I had the prospect of two execution squads: Hoxha's and the revolutionary one!" confessed Shehu later.

The height of the revolution naturally was Hoxha's ousting, show trial, and execution

Algeria, Mauritania, Libya and Senegal

Algeria's communist ruler since 1979 was Chadli Bendjedid. And, although or even because he was one of the most loyal Brusselsist rulers, his population got unruly. It started with an incident in Ilizi, where the Secret Police crushed a minor Tuareg rebellion. This was on August 23, 1989. Upon hearing from the developments in Southern Europe, and now with hope for freedom from Communist rule (which was always detested by the Algerians, who were devoutly Islamic even though State Atheism was enforced), demonstrators of all groups flocked to Ilizi in support of the next Tuareg demonstration held on September 7. Even the Tuareg were surprised of so much support of their cause, but more so was Bendjedid and his Bureau Politique. These demonstrations continued all through autumn, and increasingly large numbers tried to flee to Niger and Chad. The most valiant of regime opponents, after the Paris Wall fell, tried to venture into the Iberian Federation or the now free South France. This caused a brain drain, and to avoid this, Bendjedid promised free market reforms on January 3, 1990. But the demonstrations, held every Wednesday, wouldn't subside and increasingly many demonstrators threatened going over to violent means if Bendjedid didn't step down. In other words, Algeria was on the brink of civil war when Chadli Bendjedid stepped down on June 19, 1990. He called an interim, independent government (which some Communists still in it) just having the task of holding multiparty elections. Those were held on September 27, 1990, and strangely enough, Bendjedid's party won them...

Chadli Bendjedid, third and last communist ruler of Algeria. His stubbornness brought Algeria onto the brink of a civil war in May/June 1990.

The fall of communist Mauritania was similar to that of Tunisia. It was general dissent with the starkly authoritarian and by now nearly Bourguibaist regime of Moktar Ould Daddah. Although he remained staunchly equalist so that Arabs, Black Moors, and Africans were equally represented in the People's Parliament, he was just as authoritarian as Habib Bourguiba and so, his youth became more and more unruly, especially in Nouakchott. An independent trade union was founded on July 11, 1989 and several more of these organisations followed. Not much action followed strangely enough, except for massive numbers joining the SLS (Syndicat Libre et Solidaire). Daddah banned non-party sanctioned trade unions on February 20, 1990, and only this caused massive demonstrations continuing and swelling on by the day. On June 1, 1990, Daddah saw himself forced to relegalise the SLS in order to not lead Mauritania into a civil war and in order to preserve his power. But nevertheless, the demonstrations didn't subside and the people demanded democratic reforms, free elections, and the abolition of state atheism. Daddah suspected that the revolts were sponsored from neighbouring Mali and/or from other free countries, but he is not genocidal. And thus he stepped down nearly one year after the fall of the Paris Wall, on August 27, 1990.

Moktar Ould Daddah, last communist ruler of Mauritania.

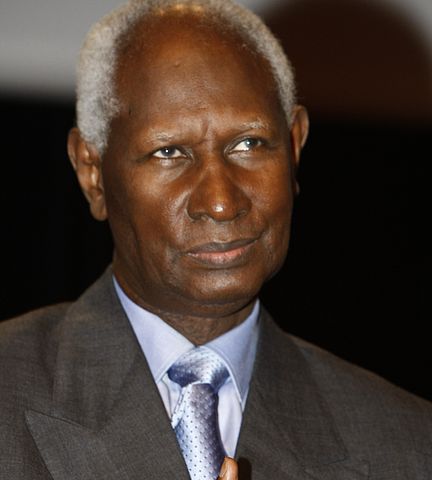

Another country to get rid of it's communist government in 1989, and thus one of the earliest to go this step, was Senegal. Abdou Diouf's fall began when in Ziguinchor, in the southwestern region of Casamance, the PNC (Parti National de Casamance) was formed illegally on August 10, 1989. The only legal party was Diouf's PSS (Parti Socialiste de Sénégal). Demonstrations in Casamance were not subsiding quickly, and Reagan refused any help, even cut the aid, so that Abdou Diouf was one of the very few Communist rulers who stepped down without even one mass demonstration having taken place; Diouf took that step on September 9, 1989, allowed travel abroad, and disbanded the secret police. Senegal was now a free country, and multi-party elections could be held on December 21, 1989, which the PR (Parti de Reconstruction) won in a landslide, though not in Casamance. There, the PNC won 74,1 % of the vote and demanded independence for Casamance. Although the main PNC is a peaceful and democratic party seeking the peaceful independence of Casmance, it unfortunately has an armed wing called the MALC (Mouvement armêé pour la liberation de Casamance) which with tactical support from the PNC, declares the independence of Casmance from Senegal, and drags the Southern region of Senegal into a civil war...

Abdou Diouf, the communist ruler of Senegal who stepped down out of his own free will, just needing to be “helped” a bit by Casamance separatists.

Biafra

Lacina Emenike Ikpeba, the ruler of communist Biafra, was ousted in a popular revolution similar to the other communist rulers of Europe and North Africa, but here, more violence and some more factionalism (Igbo and Hausa from Nigeria supported the rebel's cause in the wrong hope that they could achieve reunification with Nigeria) was involved. But the revolution, although there were violent sections (among them violent Islamists) involved, did not turn massively bloody. Ikpeba stepped down and relinquished the Communist Party's power monopoly on March 8, 1990.

Developments outside of Europe and North Africa

There also were developments which took place outside of the continents of Europe and Africa.

Over in Ecuador, the American backed Communist government of Hector Ruiz, that was formed after the ouster of the Inja Roja back in the 1970's, collapsed under heavy pressure from violent protests throughout Ecuador, a provisional Ecuadorian government was formed on January 19th, 1990, and a provisional parliament in a surprising move, declared there intentions and the Ecuadorian people's intentions to turn Ecuador into a Constitutional Monarchy, it was convened and decided a monarch would be the best solution to ensure the stability and unity of the Ecuadorian people, and thus the Kingdom of Ecuador was proclaimed on March 19th, 1990, with elections to find a candidate to assume the Ecuadorian throne commenced throughout 1990, nobles from most European royal houses offered themselves for the job, but in a surprising twist, on June 8th, 1990, the Ecuadorian parliament declared Archduke Karl, the son of former Austro-Hungarian Emperor Otto I, of the House of Habsburg had won the Election for the Throne, on June 9th, Karl, his wife, there two children and parts of the Habsburgs, who had been exiled in Sweden since the end of World War II, flew to Ecuador, where Archduke Karl was proclaimed "King of all the Ecuadorians" on July 1st, 1990, in the Ecuadorian capital of Quito.

Praça dos Três Poderes (Square of the Three Powers)

Most importantly, Brazil's students staged protests in several major cities in Maj and June 1989. They, just as in many other communist countries, demanded democratic reforms and economic liberalisation. This was triggered by the death of Tancredo Neves, the liberal and economically reformist successor of Hector Lula (whom died in 1976) and by the hope of the population would be equally or even more liberal. This hope was stifled on April 22, 1989 when the PCB (Partido Comunista do Brasil) designated João Amazonas, an arch-Lulaist and autocratic man who easily made friends with a certain Habib Bourguiba. And against this choice there were protests on Praça dos Três Poderes and in other cities of Brazil. University students who marched and gathered in Praça dos Três Poderes to mourn Tancredo Neves also voiced grievances against inflation, limited career prospects, and corruption of the party elite. They called for government accountability, freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and the restoration of workers' control over industry. At the height of the protests, about a million people assembled in the Square. The government initially took a conciliatory stance toward the protesters. The student-led hunger strike galvanized support for the demonstrators around the country and the protests spread to 400 cities by mid-May. Ultimately, the General Secretary of the PCB and Brazil's

de facto Head of Government, João Amazonas, and other party elders resolved to use force. Party authorities declared martial law on May 20, and mobilized as many as 300,000 troops to Brasilia

The Brazilian government declared martial law on 20 May, and mobilized at least 30 divisions from five of the country's seven military regions. At least 14 of PLA's 24 army corps contributed troops. As many as 250,000 troops were eventually sent to the capital, some arriving by air and others by rail. Brasilia's civil aviation authorities put regular airline tickets on hold to prepare for transporting military units.

The Army's entry into the city was blocked at its suburbs by throngs of protesters. Tens of thousands of demonstrators surrounded military vehicles, preventing them from either advancing or retreating. Protesters lectured soldiers and appealed to them to join their cause; they also provided soldiers with food, water, and shelter. Seeing no way forward, the authorities ordered the army to withdraw on 24 May. All government forces retreated to bases outside the city. While the Army's retreat was initially seen as 'turning the tide' in favour of protesters, in reality mobilization took place across the country for a final assault.

Conservative party elders such as former President Diogenes Arruda supported the enforcement of martial law by force. The PCdoB and it's Ministry of State Security issued reports on June 1 and 2 calling the protestors “terrorists and counter-revolutionaries”, thus cementing the decision to clean Three Powers Square by using deadly force. On June 2, the movement saw an increase in action and protest, solidifying the PCdoB’s decision that it was time to act. Protests broke out as newspapers published articles that called for the students to leave Three Powers Square and end the movement. Many of the students in the Square were not willing to leave and were outraged by the articles. They were also outraged by

Brasilia Daily’s June 1 article “Three Powers, I Cry for You”, written by a fellow student who had become disillusioned with the movement, as he thought it was chaotic and disorganized. In response to the articles, thousands of students lined the streets of Brasilia to protest against leaving the Square. On the morning of June 3, students and residents discovered troops dressed in plain clothes trying to smuggle weapons into the city. The students seized and handed the weapons to Brasilia Police. The students protested outside the New Brazil Gate and the police fired tear gas. Unarmed troops emerged from the Great Hall of the People and were quickly met with crowds of protesters.Scores were hurt in the scuffle. Eventually both sides sat down and sang songs, and then the troops retreated back into the Hall. At 4:30pm on June 3, senior officials, among them the mayor of Brasilia, finalized the order for the enforcement of martial law, as follows:

- The operation to quell the counterrevolutionary riot was to begin at 9:00 pm

- Military units should converge on the Square by 1:00 am on June 4 and the Square must be cleared by 6:00 am.

- No delays would be tolerated.

- No person may impede the advance of the troops enforcing martial law. The troops may act in self-defense and use any means to clear impediments.

- State media will broadcast warnings to citizens.

The order did not explicitly contain a shoot-to-kill directive but permission to "use any means" was understood by some units as authorization to use lethal force. That evening, the leaders monitored the operation from the Great Hall of the People.

The Pra[FONT=Times New Roman, serif]ç[/FONT][FONT=Times New Roman, serif]a dos Três Poderes on June 3, 1989, just before the People's Liberation Army of Brazil begins the all-out crackdown, killing hundreds or thousands of civilians in the process.[/FONT]

On the evening of June 3, state-run television warned residents to stay indoors but crowds of people took to the streets, as they had two weeks before, to block the incoming army. PLA units advanced on Brasilla from every cardinal direction. At about 10:00 pm, the 38th Army opened fire on protesters about 10 km west of Three Powers Square. The crowds were stunned that the army was using live ammunition and reacted by hurling insults and projectiles.

At about 10:30 pm, the advance of the army was briefly halted at Ceilandia, about 5 km west of the Square, where articulated trolleybuses were placed across a bridge and set on fire. Crowds of residents from nearby apartment

blocks tried to surround the military convoy. The 38th Army again opened fire, inflicting heavy casualties. According to the tabulation of victims by Three Powers Mothers, 36 people died at Ceilandia The 38th Army used armored personnel carriers (APCs) to ram through the buses, and continued to fight off demonstrators, who hastily erected barricades and tried to form human chains. Fatalities were recorded all along Goiania Avenue, The killings infuriated city residents, some of whom attacked soldiers with sticks, rocks and Oppenheimer cocktails, setting fire to military vehicles. The Brazilian government and its supporters have attempted to argue that the troops acted in self-defense and seized upon troop casualties to justify the use of force. There were reports of soldiers being burned alive on the street and others were beaten to death. The lethal attacks on troops occurred after the military had opened fire at 10:00 pm on June 3 and the number of military fatalities caused by protesters is relatively few compared to hundreds of civilian deaths.

At about 12:15 am, illumination rounds lit up the sky and the first armored personnel vehicle appeared on the Square from the west. At 12:30 am, two more APCs arrived from the South. The students threw chunks of cement at the vehicles. One APC stalled, perhaps by metal poles jammed into its wheels, and the demonstrators covered it with gasoline doused blankets set on fire. The intense heat forced out the three occupants, who were swarmed by demonstrators. The APCs had reportedly run over tents and many in the crowd wanted to beat the soldiers. But students formed a protective cordon and escorted the three men to the medic station by the History Museum on the east side of the Square.

Pressure mounted on the student leadership to abandon non-violence and retaliate against the killings. At one point, Thiaga picked up the megaphone and called on fellow students to prepare to "defend themselves" against the "shameless government." But she and Armando dos Santos agreed to adhere to peaceful means and had the students' sticks, rocks and glass bottles confiscated. The Army and Air Force began to seal off the Square from reinforcements of students and residents, killing more demonstrators. The remaining students, numbering several thousand, were completely surrounded at the Monument to the People's Heroes in the centre of the Square. At 2 am, the troops fired shots over the heads of the students at the Monument. At about 2:30 am, several workers near the Monument emerged with a machine gun they had captured from the troops and vowed to take revenge. Thiaga, Armando dos Santos and Ronaldo Moreira initially refused to withdraw. At 3:30am, at the suggestion of two doctors in the Red Cross camp, Marcio Evaldo Amoroso agreed to attempt to negotiate the soldiers. They rode in an ambulance to the northeast corner of the Square and spoke with the political commissar of the 38th Army's 336th Regiment. The commissar told Marcio, "it would be a tremendous accomplishment, if you can persuade the students to leave the Square.

At 4:00 am, the lights on the Square suddenly turned off, and the government's loudspeaker announced: "Clearance of the Square begins now. We agree with students' request to clear the Square." The students sang

The Internationale and braced for a last stand. Marcio returned and informed student leaders of his agreement with the troops. At 4:30 am, the lights relit and the troops began to advance on the Monument from all sides. At about 4:32 am, Marcio Evaldo Amoroso took the student's loudspeaker and recounted his meeting with the military. Many students, who learned of the talks for the first time, reacted angrily and accused him of cowardice.

The soldiers initially stopped about 10 meters from the students. The first row of troops took aim with machine guns in the prone position. Further back were tanks and APCs. Nevertheless, some of the students and professors persuaded others still sitting on the lower tiers of the Monument to get up and leave, while soldiers beat them with clubs and gunbutts and prodded them with bayonets. Witnesses heard bursts of gunfire. At about 5:10 am, the students began to leave the Monument. They linked hands and marched through a corridor to the southeast, though some departed through the north. Those who refused to leave were beaten by soldiers and ordered to join the departing procession. After securing the Square, the military sent in helicopters to pick up large plastic bags piled by soldiers.

The Praç[FONT=Times New Roman, serif]

a dos [/FONT][FONT=Times New Roman, serif]Três Poderes (Three Powers Square) massacre had thus been committed, Brazil did not democratise along with much of the Havana Pact, but instead Jo[/FONT][FONT=Times New Roman, serif]ã[/FONT][FONT=Times New Roman, serif]o Amazonas [/FONT][FONT=Times New Roman, serif]chose to use deadly force on innocent civilians to remain communist. [/FONT]

An equally atrocious act and an equally grave violation of international law had nothing to do with Communism, but ironically it was right near the borders of one of the major Communist states, and it was committed by the same Hugo Banzer who had already invaded helpless Paraguay in order to make good on his promise to expand Bolivia to it's historical borders. In 1983/84, he wanted the Chaco, and now he wanted to take revenge for the Salpeter War from about 100 years earlier. On 2 August 1990, using the excuse of Chile not being able to pay it's debts to Bolivia, Hugo Banzer and Bolivia invaded what he still called the Litoral Department with highly trained mountainous troops and heavy Air bombing, and within two days of intense combat, most of the Chilenian Armed Forces were either overrun by the Bolivian Republican Guard or escaped to neighboring Argentina and Paraguay. The Department of Litoral was annexed, and Banzer announced in a few days that it was the 10th Department of Bolivia.

[FONT=Times New Roman, serif]

the President of Bolivia, Generalissimo Hugo Banzer is shown here during the Atacaman War, speaking to the people of the former Paraguayan capital of Asunción, about Paraguay's annexation into Bolivia[/FONT]

However, Banzer and Bolivia was not satisfied with just the Littoral Department, his armed forces proceeded to turn there armies eastwards and launch a invasion of the tiny Paraguay, this time, Paraguay's armed forces were even less prepared for invasion then they had been in 1983, and Paraguay was overrun in a mere 5 days by the Bolivian Army, who marched into the Paraguayan capital of Asunción, which had been abandoned and left to the Bolivians by the retreating Paraguayan army, on August 11th, 1990, the city was captured and the Bolivian flag was raised above the city at 3:25 PM the same day, the rest of the country capitulated easily over the next day and the surviving elements of the Paraguayan Army, along with the now government in exile fled to Argentina or Brazil, Hugo Banzer, in the vein of Nasi leader Jean-Claude Geymere, delivered a speech on the balcony of the Paraguayan Presidential Palace in downtown Asunción in person to the crowd of over 50,000, declaring Paraguay's annexation into Bolivia as the 11th and 12th Department's of Bolivia, Chaco and Estefinca (Eastland), respectively...........