You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

To be a Fox and a Lion - A Different Nordic Renaissance

- Thread starter Milites

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 37 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 26: White Rose Victorious Chapter 27: The One Good Harvest Map of Denmark and Schleswig at the End of the Late Medieval Period (ca. 1490-1513) Chapter 28: On the Shores of a Restless Sea Chapter 29: A Thorny Olive Branch Chapter 30: Via Media Chapter 31: The Garefowl Feud Chapter 32: The Queen of the Eastern SeaThat is a gorgeous map.

Damn, that is a beautiful map.

Look at that map :0

Thanks guys! Although it was originally featured in Chapter 10, I thought it useful to have it here as well, given the fact that the character summary mentions a lot of different locations.

Chapter 16: The Sting of the Silver Nettle

Chapter 16

The Sting of the Silver Nettle

“The poor Danes, however, were subjects and acted against their ruler without command from God, and the Luebeckers advised them and helped them. Thus they took upon themselves the burden of others’ sins and mixed themselves up and entangled themselves and tied themselves up to this rebellious disobedience toward both God and man, not to mention the fact that they despised the emperor’s commands.”

Martin Luther: Whether Soldiers, Too, Can Be Saved, 1526

“And also if the Crown happen (as it has done) to come in question, while either part takes the other as traitors, I will well there be some places of refuge for both.”

Sir Thomas More: The History of Richard III, 1513

“God willing we shall see Denmark again.”

Hans Mikkelsen, upon taking ship for Mecklenburg, 1522[1]

The Sting of the Silver Nettle

“The poor Danes, however, were subjects and acted against their ruler without command from God, and the Luebeckers advised them and helped them. Thus they took upon themselves the burden of others’ sins and mixed themselves up and entangled themselves and tied themselves up to this rebellious disobedience toward both God and man, not to mention the fact that they despised the emperor’s commands.”

Martin Luther: Whether Soldiers, Too, Can Be Saved, 1526

“And also if the Crown happen (as it has done) to come in question, while either part takes the other as traitors, I will well there be some places of refuge for both.”

Sir Thomas More: The History of Richard III, 1513

“God willing we shall see Denmark again.”

Hans Mikkelsen, upon taking ship for Mecklenburg, 1522[1]

On the 26th of May, the Gottorpian main army arrived outside Hønborg Castle. Erik Krummedige made several attempts to secure free passage for himself and the garrison in exchange of an honourable surrender of the small fortress, but the ducal high-command refused. The king’s retreat to Zealand and Mogens Gøye’s relief of Bygholm Castle had convinced Frederick and his Holstenian commanders that their reckoning with Christian II would not be a swift affair. Consequently, there could no longer be any middle ground. Their cause was now that of the Tyranicedes and their battle-cry one with no room for quarter or compromise. When Krummedige did not respond to Frederick’s final call for unconditional surrender (in effect more or less a copy of the letter sent to Oluf Rosenkrantz), the rebels stormed the castle. After no more than an hour of half-hearted resistance, the vastly outnumbered garrison surrendered and delivered their commander to the enemy.

Erik Krummedige was hauled before a drum-head court headed by the duke and a delegation of Jutish councillors. In a matter of minutes he was convicted of treason, sentenced to death and executed. The swiftness of his trial was highly controversial for the times, civil war or not. As the ducal chancellor Uttenhof wrote: “... lord Erik came before the king’s tent and at once had his head smitten off.” Furthermore, for a political party whose sole claim to legitimacy was the defence of the realm’s constitution, the execution of Krummedige proved a shocking display of indifference towards the law’s appliance. It was the ascending aristocratic regime’s signal to the wavering members of the noble estate that they were not kidding around.

From Hønborg, Frederick himself proceeded North to Viborg to formally receive the acclamation and homage of his Jutish council. Meanwhile, Johann Rantzau mobilised the Holstenian shock troops for an all-out assault on the loyalist remnants in Eastern Jutland. Four days after the capture of Hønborg, Rantzau smashed a peasant host outside the city walls of Horsens, thus rendering the loyalist strong-point of Bygholm wide-open for assault. As Bygholm was little more than a fortified manor, Mogens Gyldenstjerne had no illusions of his own ability to withstand a concerted assault by the professional Holstenian mercenaries. Consequently, he resolved to retreat across the Belts.

After seizing Bygholm, Rantzau continued North and on the fifth of June he dispersed Mogens Gøye’s levies in a pitched battle outside Skanderborg. At the urging of his advisors and fearful that the Holstenians would treat him “... as they had treated other of the king’s captains… ” the royal stadtholder in Jutland left the castle under the command of a lieutenant and withdrew to the episcopal see of Aarhus. However, when the rebel main host swept in to envelop Skanderborg castle, Gøye’s commander only put up a token resistance. As soon as the ducal artillery train arrived the castellan opened his gates for the Frederickian troops. By the end of June Rantzau’s Landsknechts had subdued all of the major castles in Eastern Jutland. On the entire peninsula, only the fortress of Kaløhus and the market town of Aarhus held out for the king.

Meanwhile, Frederick had journeyed to Viborg - the epicentre of the Jutish revolt - where, in ancient times, it had been customary for every king to receive his subjects’ acclamation at the hallowed regional assembly (the landsting). Outside the city gates, the ducal party, with their Holstenian banners[2] fluttering in the summer wind, reined in their horses in front of Predbjørn Podebusk and the rebellious bishops, each with a knee in the dust. The hallowed nature of a Viborg acclamation was immediately exploited by the Gottorpian propagandists: Contrary to the reformer Christian II, Frederick enshrined a return to the old order in all ways - be they spiritual or temporal. However, this kowtowing to tradition favoured the nobility more than the duke. If the council of the realm truly was the legal head of the body politic, then Frederick must logically be delegated to the role of a glorified care-taker. In other words, the councillors possessed a permanent authority whilst the king’s was fleeting. Still, as the Holstenian field-marshall, Rantzau, dryly noted “... the lords of Jutland might have the law, but my master has an army.”

The Beheading of John the Baptist by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1515. The execution of Erik Krummedige foretold the level of sheer brutality with which the civil war was going to be fought. The Danish aristocracy was an incredibly tightly-knit caste and for one side to summarily execute a member of the opposing faction created deep cleavages within the noble community.

Consequently, the negotiations between Frederick and his new Jutish subjects over the stipulations of his accession charter were exceedingly hard-fought. Indeed, the duke bitterly complained in a letter to Uttenhof that the talks in Viborg had been the “... hitherto hardest battle of this evil feud.” Eventually the two parties came to terms, united in their desire to rid the realm of Christian II’s governance. On Saint John’s Eve, Monday the 23rd of June 1522, Frederick I was proclaimed king of Denmark by the Lords Declarent. The restrictions of his accession charter were the harshest any king had ever been forced to sign, yet to the duke it mattered little. He now possessed a claim to the throne acknowledged by a significant part of the aristocracy. All that remained was to drive him nephew from the realm. As Frederick himself declared to his councillors and commanders, it was time that “... my beloved nephew truly felt the sting of the nettle.”[3]

Two weeks later, Johann von Rantzau, Frederick I and the Jutish lords had returned to Hønborg where the major part of the Holstenian army was encamped. In the narrow waters of the Little Belt a small squadron of the royal navy prevented the rebels from crossing over to Funen. However, the majority of Christian’s fleet had followed him to Zealand in order to facilitate the redeployment of loyalist troops from the Sound Provinces to the front. On the 6th of July, a fleet of Hanseatic warships from the cities of Rostock, Wismar and Lübeck had combined off Fehmarn, hoping to avenge the defeat suffered at the hands of Norby in late May. Four days later, the Wendish navy entered the Little Belt and swept the royal vessels out into the waters of Kattegat. Resolving to press his advantage, Frederick ordered an all out assault on Funen to begin.

On the 11th of July, Hindsgavl surrendered to the advancing Gottorpian troops. Unlike in Jutland, the peasantry was far less accommodating for the duke’s men and several farmsteads and outlying villages in the hundreds of Vends and Ruggård were torched for their defiance. The king’s commander on Funen, Peder Ebessen Galt, the fief-holder at Næsbyhoved[4], withdrew from his initial position outside Ruggård castle towards the steep hill of Dyred, some 10 kilometers East of Odense. Although he only had a quarter of an infantry fähnlein, a few hundred mounted noble retainers and squires and some two thousand peasant levies at his command, Galt was determined to prevent the forces of the Holstenian pretender from marching straight across the island unopposed.

A week after the duke had landed on Funen, Frederick’s army deployed below the loyalist host and immediately began to ascend the hill. Although the ensuing battle was the hitherto largest engagement of the war, it was over in a matter of hours. At first, Galt’s mercenaries withstood the charge - aided in good part by the lightly armoured peasant levies, but as soon as Rantzau’s right flank began to envelop their position, the loyalist nobles lost their nerve and fled. Mortally wounded in the ensuing rout, Peder Ebessen Galt was none the less carried by a few loyal servants off the field and transported to the strong fortress of Nyborg to die. The following morning, the duke’s bloodied and torn banners were paraded through the streets of Odense. For all intents and purposes, all of Funen had fallen into the hands of the Frederickians: The icing on the cake being the willing enrollment of all surviving loyalist Landsknechts in the Holstenian army.

To the king the news of the rebel landing on Funen and Galt’s subsequent defeat at Dyred Hill came as an immense shock. Although he had held no illusion as to Mogens Gøye’s ability to hold Eastern Jutland in the long run, the rapidity with which the rebels had seized the peninsula and half of Funen darkened his mood considerably. Some historians have suggested that Christian II for a moment considered relocating his court to the Netherlands in order to personally garner support from the emperor[5], but the arrival of Gøye, Gyldenstjerne and other loyalist nobles in the capital cemented his will to face his uncle head on at home.

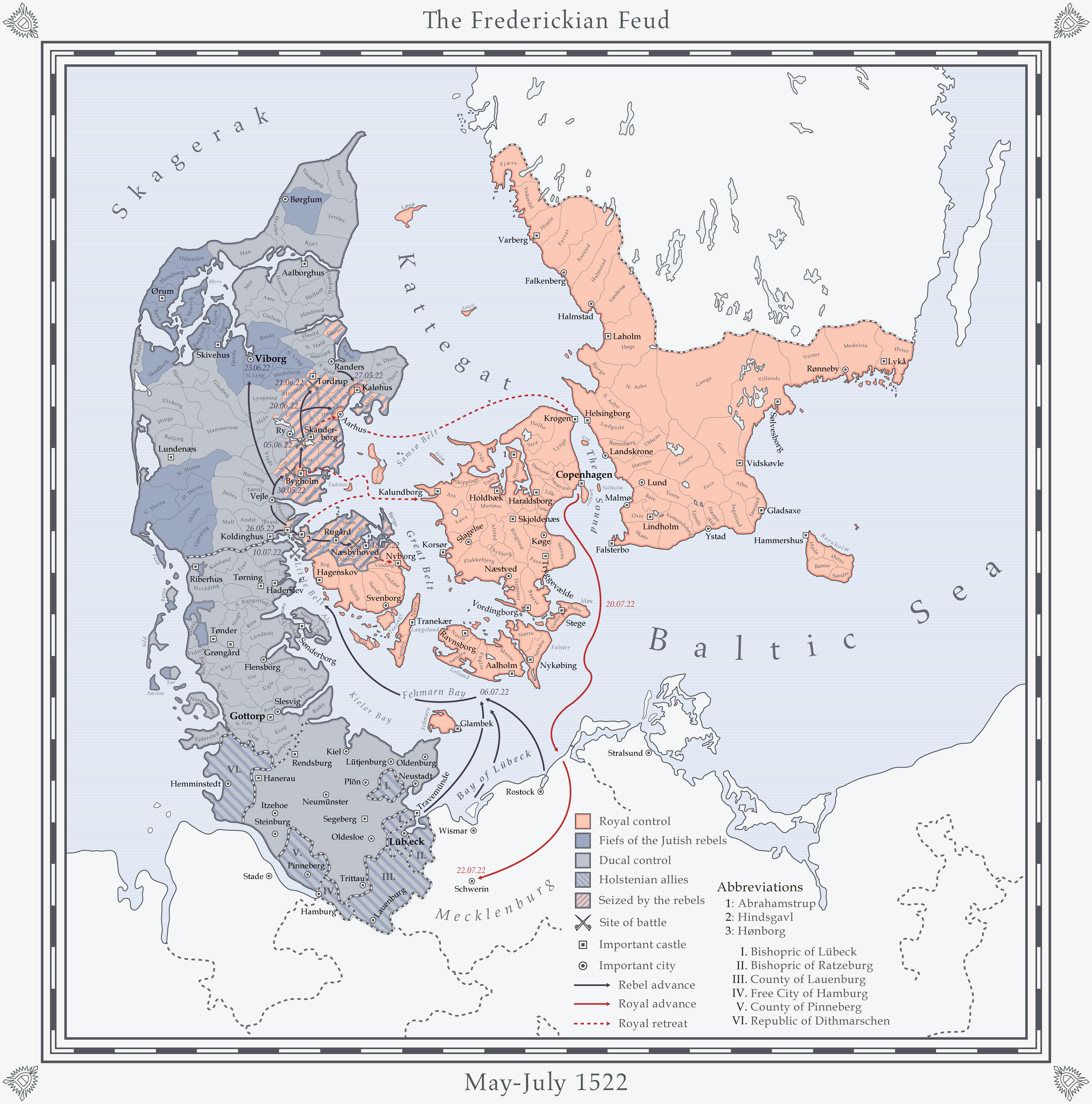

The Frederickian offensive into loyalist Eastern Jutland and Funen. May-July 1522.

Instead, the king threw himself into organising the royal forces. Otte Krumpen had come over from Helsingborg with the entire might of the Scanian rostjenese, some 500 knights and retainers, whilst Torben Oxe and Eske Bille had raised the levies of Northern Zealand. All in all, the king had a host of some 6000 peasants, around a thousand noble retainers and half a fähnlein of Landsknechts at his disposal. A force significant enough to give the Holstenians pause, it was hoped. Furthermore, messengers had already departed for Norway at the beginning of June, commanding Karl Knutsson at Bohus castle to raise emergency taxes and bring whatever men he could spare from his garrison down to Zealand.

Additionally, loans had been obtained from the burgher strongholds around the Sound Provinces. Hans Mikkelsen, the mayor of Malmø, in particular proved himself an eager contributor the royal cause. Thanks to Mikkelsen’s efforts, a huge amount of funds was raised to fill the crown’s war chest. Zealand and Scania, however, was never the less subjected to a harsh call for extra taxes - an act which severely damaged the king’s reputation as a friend of the commons. Popularity aside, the extra revenue meant that Christian II now possesed the means to stave off an attack on Zealand, but if he were to go on the offensive, he needed mercenary muscle.

Although the Gottorpian coalition had sealed off the approaches of the Elbe as a marshalling area for fresh Landsknecht companies, both the Duke of Mecklenburg and the Prince-Elector of Brandenburg had openly declared their support for Christian II. As often the case in late medieval and early modern Europe, diplomatic relations largely depended on family ties: Joachim I Nestor of Brandenburg was married to Christian’s younger sister, Elisabeth, whilst Albrecht VII of Mecklenburg-Schwerin was betrothed to their oldest daughter, Anna[6].

Hoping to turn these connections to his advantage, Christian dispatched an embassy to the Mecklenburgian court in Schwerin. The embassy was headed by Hans Mikkelsen, seconded by Albert Jepsen Ravnsberg, the most skilled diplomat in the king’s service, and Ove Bille, the bishop of Aarhus, who had fled his episcopal see in the face of the rebel offensive. Mikkelsen’s task was centred on raising as many mercenary companies as possible and to secure their transportation to Zealand. Ravnsberg and Bille, conversely, would only be passing through. First of all, the king commissioned them to persuade Albrecht into intervening directly against the lesser Wendish cities of Rostock and Wismar. In exchange, Christian hinted at a possible revision of the feudal suzerainty over the county of Lauenburg. It was a bold proposition, as the right of enfeoffment was the emperor’s and thus not within Christian’s power to barter with. Nevertheless, it was testament to how much stock the king put in his relationship with Charles V.

From Schwerin, the noble commissioners were to continue on to Berlin, where they hoped to convince the king’s brother in law to lend Christian monetary and, if possible, military assistance. Finally, Ravnsberg and Bille were to journey to Brussels to request imperial action against Lübeck and the other German states supporting the Frederickian Party. On the 22nd of July, the embassy entered Schwerin after a dangerous voyage across the Baltic. Being well-received by duke Albrecht, Hans Mikkelsen immediately went to work and by the middle of August had already signed the first Landsknecht company. Slowly, but steadily, the outskirts of Schwerin became more and more crowded with the white canvas tents of the Landsknechts.

By then, however, a rapid series of events in the Eastern part of the Union had threatened to undo all of the king’s plans.

Judith With the Head of Holofernes by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1530. Besides a small effigy in Västerås Cathedral, no delineation of Lady Kristina Nilsdotter Gyllenstierna remains today. However, it is difficult not to see her likeness in Cranach’s painting of the biblical heroine Judith. Like Judith, Lady Kristina was a widow with an iron will determined to avenge her people. It has been noted by some art historians that the severed head of Holofernes bears a striking resemblance to Christian II.

From her court at Tavastehus, the exiled Lady Kristina Nilsdotter Gyllenstierna had begun to spin a web of her own. When news of the duke’s invasion of Jutland and Christian II’s rout off the peninsula arrived in Finland in early May, the lady called a general muster of her supporters. In a matter of days, the remnants of the vanquished Sture Party sprang out of the Finnish wood-work led by Arvid Kuck, bishop of Åbo. Although centred on the fiefs of Finland, Satakunda, Nyland and Tavastehus, the Sture widow also commanded loyalty in the remaining, peripheral fiefs of Österbotten, Savolaks and Karelen (Karelia), essentially rendering the Eastern half of the Swedish realm an autonomous kingdom.

Amongst the most prominent Sture partisans were Nils Eriksson Banér, fief-holder at Raseborg, Bengt Arendsson Ulv, Måns Gren and Magnus Eriksson Vasa, younger brother of the late Lord Steward’s personal standard bearer. When the Sture conspirators learned of the Jutish rebels’ continued successes, they concluded that the time to strike back had finally come. The royal government in Stockholm was not oblivious to the brewing unrest in Finland. Indeed, Henrik Krummedige wrote despairingly to the king of Lady Kristina’s “... evil conspiracies and treasons”[7], but the viceroy dared not act against her without concrete proof.

He would not have to wait long for the Lady to show her hand.

On the 25th of May, Arvid Kuck called a diet of the estates in the Finnish provinces. Delivering a fiery speech denouncing the Oldenburg government in Sweden proper by specifically targeting the king’s coup at Christmastide 1519 as a breach of the council of the realm’s electoral prerogative, the bishop of Åbo urged the delegates to seize the moment, sail across the Baltic and liberate the realm from the evil practices of Christian II. The time was perfect, Kuck claimed, as the king had supposedly been driven from Denmark by his very own councillors. Although the Sture reports were faulty at best, a definite sense of ‘now or never’ took charge of the delegates. There was, however, the small problem of who were to lead the Sture cause.

Lady Kristina had proven herself a skilled administrator and ruthless politician during her tenure of stadtholder in Stockholm. She had acted decisively in executing Steen Kristiernsson Oxenstierna and skillfully organised the capital’s defense while her husband was in the field. Furthermore, her maternal grandfather had been the last native king of Sweden: Karl Knutsson Bonde. This claim she had unified with that of her husband, the late Sten Sture the Younger, who was also a descendant of Bonde on his father’s side. As such their children, Nils Stensson Sture and Svante Stensson Sture combined the prestige of the Bonde monarchy with that of a long line of Sture Lord Stewards. Thus, there was little doubt as to on whose brow the crown of liberated Sweden should be placed[8]. Unfortunately, Kristina’s oldest son Nils was a captive in Copenhagen and his younger brother Svante was a mere five years of age.

However able she might have been, the Lady Kristina could not lead an army nor formally assume the Lord Stewardship. So while the fact that the young Svante Stensson should become Lord Steward, with his mother as acting regent, was uncontested, the Åbo lords could not agree on who should lead their forces in the field. The question threatened to seriously hamper the Sture cause and was only resolved when one of the most famous participants in the Unionist Wars rose to the occasion.

The relations between the great anti-unionist families of Sweden: Bonde, Sture and Vasa.

Given the first name of several Scandinavian monarchs, Magnus Eriksson was a strapping 21 years old youth; the scion of one of Sweden’s most powerful anti-union families. His brother had been the standard bearer of the late Lord Steward, whilst his father’s uncle had been the venerable Sten Sture the Older, the celebrated victor of Brunkeberg. On the third day of the Åbo convocation, Magnus forcefully declared that he would be willing to go West and raise the people against the foreigners and oppressors. One by one, the Sture lordlings gave him their consent and elected him to the military office of Lord Captain of the Realm (Rikshövitsman). Officially he was subservient to the young Lord Steward and his regent, the Lady Kristina, but in effect Magnus Vasa would operate independently and with his own authority as soon as he landed in Sweden. It is a testament to his apparent influence that Henrik Krummedige wrote to the king that Magnus had promised Kristina “... that she and and her child would be placed at the head of the realm’s government, to which folly she has led herself be deceived.”[9]

By the middle of June, Magnus Eriksson had crossed the Sea of Åland and landed on the Gästrikland coast with a few hundred supporters. The town of Gävle opened its wooden gates immediately, whereupon the young Lord Captain was carried through the streets on the shoulders of jubilant townsmen. The king’s sheriffs and officials, conversely, were violently driven from the town. The government’s response was swift and forceful. 200 mounted Landsknecht and as many noble retainers under the command of Reinwald von Heidersdorf and Mauritz von Oldenburg[10] rode up-country from Stockholm, catching the Sture household troops unaware.

Magnus fled West with a substantially reduced retinue, the royalist riders in hot pursuit. Seeking refuge in the forested hills of the Dalarna uplands, the Lord Captain was almost captured during a small skirmish with Heidersdorf’s hunters, but once again the viceregal hand clasped around thin air. Every time Magnus Eriksson avoided capture his statue grew amongst the commoners. His continued evasion lulled the Stockholm government into such a sense of security that Krummedige could report to Copenhagen that “... the bastard Vasa has vanished from the realm.”

It was, however, a premature conclusion. Around midsummer, Magnus Eriksson suddenly appeared in Dalarna. The unruly Dalecarlian hundreds had never truly resigned themselves to Christian’s government and had previously served as the centre for uprisings against the Oldenburg triple monarchy. Indeed as Hemmingh Gadh had once quipped “the Dane and the Devil both feared Dalarna.” At Tuna he raised the peasantry and commoners against the royal sheriffs before hurrying off towards Mora.

On the feast day of Saint Bridget of Sweden (Heliga Birgitta), Magnus Eriksson Vasa spoke to a large gathering of miners and free peasants in front of Mora church. Asking the commons to bear in mind the great sacrifices made by his brother and the late lord Steward and, conversely, the tyranny of the Danish crown. The great lords of the realm would not act against the oppressors, the Lord Captain argued. Only the commoners could now save Sweden and restore the law of hallowed Saint Erik. Greeted with enthusiastic support, it did not take long before the rising had spread to neighbouring Värmland with considerable unrest spreading as far South as the episcopal see of Skara, where Vincent Hemmings proved surprisingly inefficient in maintain order.

The bastard Vasa had only just begun[11].

The opening stages of the Sture rebellion in Finland and Sweden.

Footnotes:

[1]A quote from an OTL letter by Hans Mikkelsen during his exile. The original line is quite touching in its longing for home. Here, it is conversely an expression of Mikkelsen’s hope that he can serve his king abroad and return with enough troops to vindicate his liege. The original transcription reads: “Gwd giffwe wij motthe komme i Danmarck i geen.”

[2]OTL records show that Frederick meticulously ordered his supply train to carry his ducal standard.

[3]The coat of arms of the duchy of Holstein was a stylized silver nettle leaf.

[4]In OTL he had been deprived of both his Funish fiefs because of the king’s suspicion. ITTL, he maintains both of his enfeoffments.

[5]As he did in OTL.

[6]In OTL, both were extremely opposed to the usurpation of Frederick I.

[7]Being the OTL words of Gustav Vasa about the Lady Kristina.

[8]In OTL there was little doubt that Sten Sture sought to make himself king. In 1516, Christian II received reports from Rome that Swedish agents were seeking papal support for a Sture monarchy. Likewise, in 1519, Peder Månsson noted in a letter to the abbess of Vadstena Convent why the Younger Sture hadn’t been crowned yet.

[9]An OTL description of Kristina by Gustav Vasa upon hearing rumours of her being engaged to Søren Norby.

[10]Both were mercenary commanders in the service of Christian II in OTL

[11]In OTL the Dalarna rebellion was partly infused by news of the Stockholm Bloodbath, but even more so by reports of Christian II’s Eriksgata (the traditional journey through Sweden undertaking by a newly elected monarch), where he had continued to lop off heads of people he’d promised amnesty. Furthermore, the government imposed on Sweden in OTL was highly inefficient and widely despised for its cruelty. Conversely, in this timeline, it is headed by a skilled soldier and administrator (Henrik Krummedige) and several capable pro-union spiritual as well as temporal lords (Gadh and Leijonhufvud in particular). ITTL the rebellion still occurs (I don’t think it plausible for Sweden to remain completely calm given the escalating civil war in Denmark), but it’s on a much, much lower scale. In OTL, Gustav Vasa managed to take control over most of the countryside in a matter of months, with only the strongest castles withstanding him. Here, his brother is in for a much harder fight.

Last edited:

these maps... I at a lost for words to describe them, there just majestic

Shoot Denmark really in a debacle right now they have rebel to the north and to the south he may want to call and his loyal servants, the Norwegians they could hold off the threat to the north and help a lot with soldiers and naval ships to the south

Shoot Denmark really in a debacle right now they have rebel to the north and to the south he may want to call and his loyal servants, the Norwegians they could hold off the threat to the north and help a lot with soldiers and naval ships to the south

A mixed bag for Christian all told - better than OTL it seems, but certainly quite a mess! Even though I would be so bold as to say Frederick's revolt is likely doomed to failure (since the purpose of this timeline seems to be to mix up the fortunes of the Danish state) it's looking to very much fall along the razor's edge. And there's an interesting nuance in the fact that Christian's Swedish supporters are the powerful and aristocratic set and yet those are his worst enemies back in Jutland. Peasant rebellions and noble rebellions and well, I guess he just can't please anyone.

Last edited:

Awesome update and with more maps  Things are getting messy all around, Christian really is going to have to move fast here

Things are getting messy all around, Christian really is going to have to move fast here

I wonder how the peasants of Småland reacts.

Also as mentioned by someone else, there is something deeply ironic, that there is a noble revolt in Denmark, while a (somewhat) peasant revolt is going on in Sweden.

Hence the interest in Småland. Being on the border with what can be described as the core of Christian II's territory.

Also as mentioned by someone else, there is something deeply ironic, that there is a noble revolt in Denmark, while a (somewhat) peasant revolt is going on in Sweden.

Hence the interest in Småland. Being on the border with what can be described as the core of Christian II's territory.

these maps... I at a lost for words to describe them, there just majestic

Shoot Denmark really in a debacle right now they have rebel to the north and to the south he may want to call and his loyal servants, the Norwegians they could hold off the threat to the north and help a lot with soldiers and naval ships to the south

Thank you! I'm quite happy with the results myself, I should say so. Norway is going to be very valuable in the royal war effort, but its resources are already invested in the Christianian cause. A large amount of the ships in the royal navy are manned by Norwegians and sailors from the Norwegian dependencies. Other than that, there's the propaganda value of Erik Valkendorf's flybills denouncing the Stures. In OTL (and ITTL as well) the largest pilgrimmage site in Scandinavia was at Trondhjem, where Valkendorf meticulously handed out propaganda flyers branding the Stures as heretics.

Incidentally, Valkendorf is still very much alive ITTL. In OTL he appealed to the king to remove Dyveke which (understandably) incurred the wrath of Sigbrit. As a result he travelled to Rome (he had a chance encounter with the king in the Netherlands, where Christian II tried to have him imprisoned!) to argue his case at the papal court, but died of some illness before achieving anything.

A mixed bag for Christian all told - better than OTL it seems, but certainly quite a mess! Even though I would be so bold as to say Frederick's revolt is likely doomed to failure (since the purpose of this timeline seems to be to mix up the fortunes of the Danish state) it's looking to very much fall along the razor's edge. And there's an interesting nuance in the fact that Christian's Swedish supporters are the powerful and aristocratic set and yet those are his worst enemies back in Jutland. Peasant rebellions and noble rebellions and well, I guess he just can't please anyone.

Indeed, much better than OTL, but still - as you said - a mixed bag. Regarding the different nature of the Swedish and Danish rebellions: It's an interesting perspective that I hadn't considered. I think it's a testament to the different political contexts in the two realms. The Swedish aristocracy doesn't really have a choice to be honest. Lady Kristina's political programme was and is the establishment of a hereditary monarchy for her sons. Given the choice of either supporting Kristina and her disgraced partisans (remember the murder of Gustav Trolle + the much more decisive military defeat compared to OTL) and Christian II's fig-leaf adherence to the elective monarchy, it's not surprising the majority of the council of the realm (for now at least) sticks with the king.

Kristina is my girl!

Heh, it is quite difficult not to root for her. She's an extremely interesting and tenacious woman. I'm seriously toying with the idea of having her set up an independent hereditary Sture kingdom in exile in Finland if everything goes South for her.

Awesome update and with more mapsThings are getting messy all around, Christian really is going to have to move fast here

Indeed, more maps. I actually considered breaking this chapter into two smaller instalments focusing on Denmark and Sweden respectively.

I wonder how the peasants of Småland reacts.

Also as mentioned by someone else, there is something deeply ironic, that there is a noble revolt in Denmark, while a (somewhat) peasant revolt is going on in Sweden.

Hence the interest in Småland. Being on the border with what can be described as the core of Christian II's territory.

The Småland and Scanian peasants had this annoying habit of concluding their own peace treaties whenever the two realms were at war. These so-called Peasant's Peaces included provisions for the neighbouring parishes to warn each other if an attack or raid was being prepared, keep the cross-border trade open and generally more or less just ignore the whole "our two countries are at war"-thing.

I don't see the Sture rebellion affecting this very peculiar agreement. However, there is also the fact that the bishop of Växjö isn't all too keen on Christian II's reform programmes and interference. Småland was after all the epicentre of many great revolts against Gustav Vasa.

Honestly this is the wrong time for a independent Finland, it’s a easy victim of a Dano-Swedish invasion and I doubt Russia could truly defend them. Finland at this time was poor, undeveloped, had a low population and pretty much all its major cities would be easy to overrun for a enemy with a stronger navy than Finland.

Honestly this is the wrong time for a independent Finland, it’s a easy victim of a Dano-Swedish invasion and I doubt Russia could truly defend them. Finland at this time was poor, undeveloped, had a low population and pretty much all its major cities would be easy to overrun for a enemy with a stronger navy than Finland.

Yeah, and holding the inland of Finland would just make her a rebel.

and what in there that useful for finalndYeah, and holding the inland of Finland would just make her a rebel.

and what in there that useful for finalnd

Marginal farmland along the southern coast and the pine tar production along the Bothnian coastline, but both lies in areas, which are easy to control by whoever control mainland Sweden.

and it all in the coast not in the mainland so finland can't really become idnpednet anytime soonMarginal farmland along the southern coast and the pine tar production along the Bothnian coastline, but both lies in areas, which are easy to control by whoever control mainland Sweden.

Threadmarks

View all 37 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 26: White Rose Victorious Chapter 27: The One Good Harvest Map of Denmark and Schleswig at the End of the Late Medieval Period (ca. 1490-1513) Chapter 28: On the Shores of a Restless Sea Chapter 29: A Thorny Olive Branch Chapter 30: Via Media Chapter 31: The Garefowl Feud Chapter 32: The Queen of the Eastern Sea

Share: