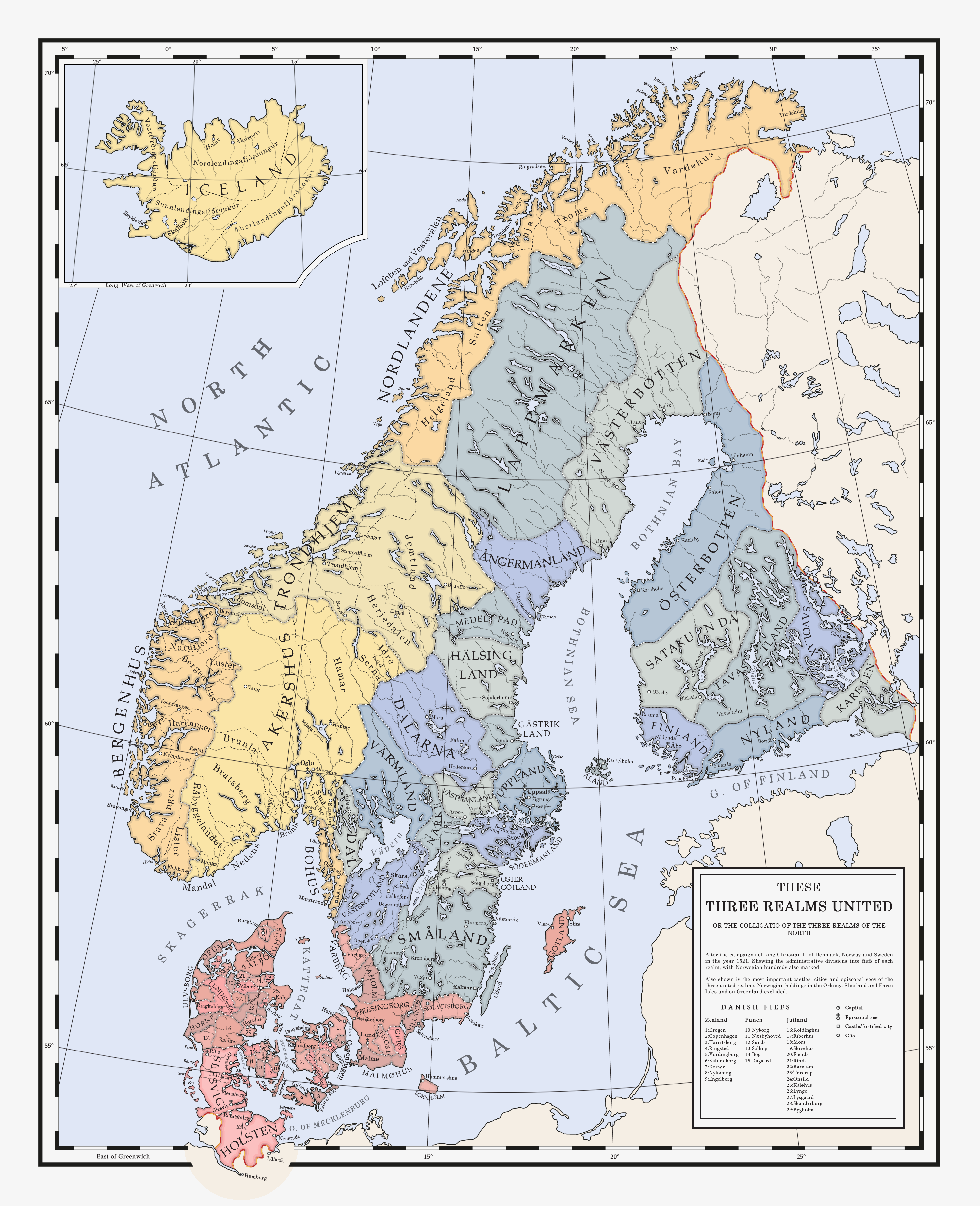

Chapter 15

When the Wind Gives In

On the 14th of May 1522, the Day of Saint Matthew the Apostle, Christian II took mass at the Franciscan convent in Odense. He had brought with him the flower of the Zealandic and Scanian knighthood: a hundred armed and armoured riders, headed by sirs Henrik Gøye and Mogens Gyldenstjerne. As the king knelt in the quire, observers noted how his auburn brow was knitted in obvious concentration. Troubling news had been crossing the Little Belt in shorthand despatches ever since the royal party came over from the capital. Some said peasants were rising against the king’s sheriffs and tax officials whilst others, conversely, claimed that the Jutish countryside was wholly at peace. We know for a fact that the king was aware that some sort of unrest was fermenting on the peninsula. In a letter to queen Elisabeth dated the previous day, Christian II wrote:

“Wiider kiere frwe, at wore raadt oc gode mend oc en stoor deell aff almwgen vtj Nöriutland haffuer saat seg vp emodt oss oc giort en stor forsamblinge oc wilde slaget met oss oc wore folck…”

“Know, dear madam, that Our council and nobles and a great part of the commoners in Northern Jutland have risen against us and made a great assembly and means to fight Us and our men…”[1]

Nevertheless, the king must have felt confident that he could bring the dissatisfied councillors back into the fold. His convictions were strengthened by the arrival of a letter written in his uncle’s very own hand, informing him that the duke was heading north to meet him at Koldinghus on the ducal border. There they could solve the Gottorpian Gordian Knot amicably. Christian II was supposedly rather pleased that Frederick had finally left his cozy nest, which he mistook for a desperate attempt to placate him. As such, he resolved to cross over to Jutland and meet his estranged uncle and receive his subordination.

Nothing, however, could have been further from the truth. The duke was indeed coming north, but his cause was revenge, not reconciliation. Neither was he travelling alone.

Frederick had raised a considerable host of between two and three thousand Frisian levies from the Western marches of Holstein, a force augmented by several companies of noble Holstenian cavalry as well as one thousand

Landsknechts and 300 armoured

Reiters. However, the urgency of the conspiracy had trumped the need for secrecy. The ducal party was desperate to finance the coming feud with the king, but had to minimize the loans obtained at the famed

Kieler Umschlag[2] in order not to draw the attention of Christian’s agents in the duchies. As such, the mercenary core of Frederick’s army was considerably smaller than what he theoretically might have been able to put in the field

[3].

The ducal army was headed by the daring cavalry commander Johan Rantzau, who had won fame and fortune during the king’s Swedish campaign three years before whilst the hired troops were commanded by the Lower Saxon condottieri captains Segebode Freytagk, Christoffer von Veltheim and Johann, the Count of Hoya

[4]. As soon as news of Christian’s crossing from Zealand to Funen reached Gottorp, Frederick marshalled his troops. On the 12th of May mounted messengers darted forth to order the equestrian nobility of the duchies to rally to the ducal cause. In Holstein, every single castle and city answered Frederick’s call, save for the royal stronghold of Segeberg and the market town of Oldesloe where, a combined force of Lübeck-financed mercenaries and Holstenian knights seized the castle and town by force. An ill-prepared sea-borne attack on the isle of Fehmern was repelled, but the Hanseatic fleet effectively quarantined the island, preventing any news of the duke’s movements from reaching the king on Funen.

At the same time, the 51 year old Frederick led his main host North from Gottorp. As in Holstein, the most important cities and castles of Schleswig opened their gates to him: only the citizens of Flensborg succeeded in repulsing the Holstenian troops

[5]. Thus, when Christian took mass in Odense, his uncle had already seized most of the duchies for himself and proceeded to link arms with a small force of Jutish knights at Tørning castle. Undeterred, the king landed in Jutland with his one hundred man strong entourage on Friday the 16th of May, determined to meet his uncle at Koldinghus and woefully unaware of the general rising, which by now was in effect throughout the peninsula.

A skirmish between cavalry during the Frederickian Feud. Engraving from the Oldenburgische Chronicon by an unknown artist, ca. 1563-99.

Word of the king’s decision to confront his uncle must have reached the councilar opposition gathered in Viborg sometime during the very first days of May. Having met around Easter, ostensibly in order to prepare for the anticipated conference between Christian and the duke, the Jutish council now sprung into action. Their undisputed primus inter pares and leader of

the Council of Denmark’s Realm in Jutland Declared, as the rebel party termed itself

[6] was Predbjørn Podebusk of Riberhus. He was seconded by the three ecclesiastical members of the council of the realm; Jørgen Friis, Iver Munk and Niels Stygge Rosenkrantz - bishops of Viborg, Ribe and Børglum respectively. Other important members of the conservative cabale were Niels Høg, fief-holder at Skivehus, and the wealthy Jutish noblemen Peder Lykke and Tyge Krabbe

[7].

During the Sunday sermon of May 11th Jørgen Friis openly preached on the merits of the Lords Declarent. In his speech, the bishop of Viborg denounced the king as a heretic who had wantonly overstepped the constitutional restraints of his accession charter and as such, proven himself to be “...

a manifest tyrant” whose governance it was every true Danishman’s duty to drive from the realm.

Afterwards, copies of the king’s secular and ecclesiastical laws were ceremoniously burned outside the cathedral, symbolically signalling the Jutish aristocracy’s declaration of an official feud against Christian II. Constitutionally speaking, the Jutish councilors had invoked the infamous

ius resistendi and their law-given right to depose the king. In his place, they themselves were to act as the temporary head of the body politic. It has been argued that even though the Jutish revolt on the whole was characterised as a reactionary reply to royal reform, it contained a revolutionary element, given how the councilar role in government was drastically reinforced. Indeed when one considers the proclamation of rebellion, it almost seems as if the conspirators dreamed of establishing a noble republic, as the initial phrasing shows:

“Thus in the name of the Holy Trinity we have united and made common cause in the defense of our honour, lives, necks and estates and have, with our own hands, signed this our declaration in order to protect and defend against, and verily never to suffer that such a man[8] should live in Denmark, Sweden and Norway [...] in this we shall utilize the highborn prince sir Frederick, by the grace of God duke etc., our noble master, who is born of true Danish blood and acts like a true Christian prince towards God and man alike [...]”[9]

Whether not Frederick was willing to let himself be “utilized” by the Jutish opposition seemingly never crossed the minds of the conspirators. Furthermore, even though the Viborg Declaration framed the councilor’s feud against Christian II as grounded in a united aristocratic front, the Danish nobility was hardly a political monolith. Indeed, some members of the lesser aristocracy voiced hopes that their demands could be met through some kind of negotiation, the “

education of the sovereign” alluded to in the accession charter. When these suggestions were put to the leaders of the rebel party, sir Podebusk exploded in anger, declaring that he and the bishops “...

would rather die in a single day or call in Frenchmen, Poles, Russians, Prussians, Muscovites or Turks to rule over them.”

[10] In other words, there could be no talk of compromise. The dice had been cast.

Once the Viborg declaration had been presented, rebel forces swept out from their staging points in Western Jutland. Eiler Bryske, the fief-holder at Lundenæs, was driven from his castle when a strong host of levied peasants under the command of Tyge Krabbe threatened to storm it and slaughter its defenders. When he arrived at Bygholm castle, he swiftly sent messengers to Funen as well as south to Koldinghus, carrying word of the insurrection and urged the king to retaliate with all his might, going so far as to even encourage the king to “...

burn down every single city and town beholden to rebellion.”

[11]

The king, however, was in no position to burn anything to the ground. On the 16th of May he and his party landed at Hønbog castle and headed towards Koldinghus. The following day, just short of the city of Kolding, they were set upon by Frederick’s van of German mercenary cavalry. After some initial confusion, the Holstenian riders launched themselves on the king’s small force. Christian II was himself badly wounded in the melee whilst more than a score of his best knights were cut down trying to defend him. Henrik Gøye was unhorsed during the skirmish and subsequently captured by the ducal troops. Accompanied by a bloodied Mogens Gyldenstjerne and no more than 50 retainers, the king fled back towards Hønborg whilst his uncle’s men withdrew to cut off the city.

Oluf Nielsen Rosenkrantz, the fief-holder at Koldinghus, initially resolved to withstand the enemy, but the arrival of the Gottorpian main force the following day drastically reduced his will to resist. After a few days of fruitless negotiations, Frederick threatened Rosenkrantz that if he persisted in “...

delaying them, then they will burn my farms and take all the estates I have in the realm…”

[12] and ordered him to surrender or face the prospect of having the fortress taken by storm. Seeing that the castle under no circumstances could withstand the enemy, Rosenkrantz resolved to heed the duke’s command. In a letter to the king, the castellan lamented his predicament and officially repudiated his oath of loyalty to Christian in favour of his uncle. However, he also stressed that he only did so out of fear of what the duke’s men might do to him and his servants, kindly attaching Frederick’s proclamation. Unsurprisingly, no account of how Christian II received these news survives.

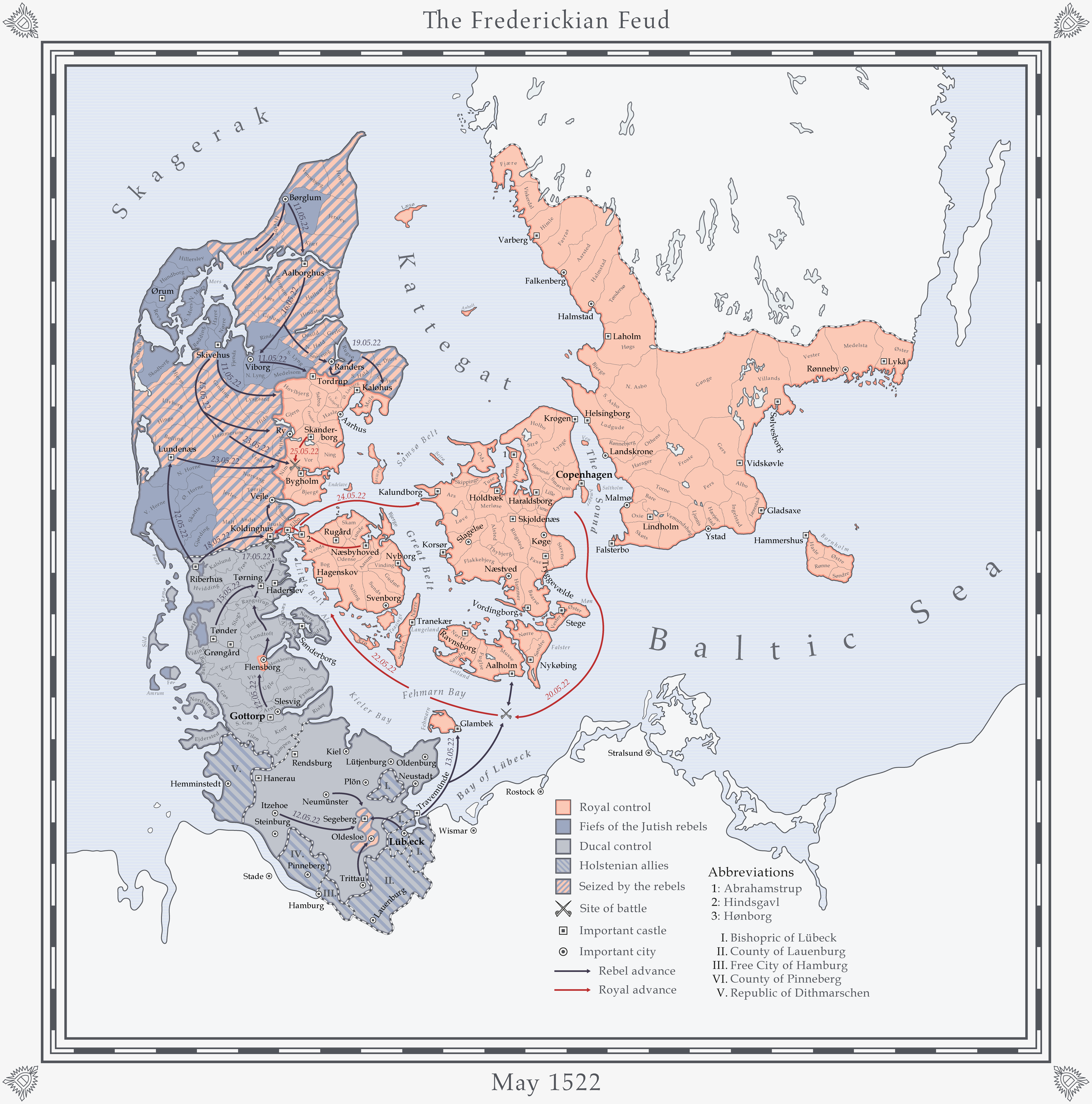

The opening stages of the Frederickian Feud, also known as the Duke’s Feud. May 1522.

As the king licked his wounds at Hønborg, reports began to trickle in from the Northernmost parts of Jutland. In Aalborg, a caretaker administration headed by Henrik Gøye’s chancery had been driven from the city when a host of levies led by the bishop of Børglum’s lieutenants descended from Vendsyssel

[13]. The rebels subsequently marched South through Aalborghus fief before splitting into two separate corps. One advanced East, seizing the Himmerland hundreds belonging to the bishop of Aarhus

[14] (who had remained loyal to Christian II) whilst the second linked arms with the main councilar army at Viborg. The only good news to come South was the fact that the strong fortresses in Eastern Jutland: Tordrup, Skanderborg and Bygholm all remained faithful. Mogens Gyldenstjerne, who held the latter as a pledge-fief, immediately petitioned the king to go North in order to raise the commoners and the local rostjeneste in his defence.

After some deliberation, Christian II gave his consent and on the 19th, Gyldenstjerne subsequently crossed the Vejle Fjord in a small boat. The castles of Tordrup and Skanderborg, which guarded the approaches to the episcopal see of Aarhus, were held by the king’s friend Mogens Gøye. When news of the duke’s invasion, the rebellion of the Jutish council and the capture of his younger brother reached Gøye at Skanderborg, he immediately called up his peasants and roused them to defend their sovereign

[15].

This proved to be a prudent move as on the 23rd of May, a 2000 man strong army of peasant levies crossed the shallow Hansted Creek and entered the hundred of Nim. Commanded by Tyge Krabbe, who had brought along a retinue of mounted knights from his seat of Bustrup near Viborg, the North Jutish levies were soon encamped outside Bygholm, with Krabbe loudly calling for its surrender.

At Skanderborg, Gøye had been alerted of the rebel advance two days previous prompting him to quickly organise a relief force consisting of some 1500 peasants augmented by a small squadron of armoured retainers sent to him by the bishop of Aarhus. The following day Gøye marched his division South, catching the rebels unaware.

At the brink of dawn on the 25th, the royalist cavalry squadron crashed through the rebel picket lines and began to torch the makeshift bivouacs and tents, sending a large part of Tyge Krabbe’s untrained (and rather unenthusiastic) peasant soldiers fleeing for their lives. Their commander was, however, a seasoned veteran of the Union Wars in Sweden and quickly restored order to his ranks by leading a counter charge on the episcopal riders.

Armed Peasants Fighting Naked Men by Hans Lützelburger

, 1522. Although both sides of the civil war mustered armies of conscripted peasants, it was widely accepted that the key to military success was the employment of mercenaries.

As soon as the Bygholm garrison became aware of the ongoing battle, Mogens Gyldenstjerne led a sortie, forcing the councilar army to retreat. However, when the two loyalist commanders shook hands on the field, they soon realised the miniscule nature of the battle. No more than a hundred men had lost their lives in the skirmish and not even that many had been captured or wounded. Indeed, it was no Bosworth or Brunkeberg. Instead, the first pitched battle of the civil war more resembled a large harvest-day brawl between confused and ill-equipped villagers. However, despite its small scale, the relief of Bygholm had been a sorely needed victory for the royalist cause as it temporarily took off some the pressure on Eastern Jutland. Still, the Northern approaches remained exposed to rebel attacks.

Tordrup castle had been besieged by a force under the command of Peder Lykke (or “

that happy swine” as Christian II named him) whilst sir Podebusk’s own retainers had struck out from his fief of Rugsø and seized the important market town of Randers as well as much of Northern Djursland, threatening the strategically vital Kaløhus. Erik Eriksen Banner, the castellan at Kaløhus, had been at Skanderborg when news of the rising arrived from Viborg and had as such also participated in Gøye’s attack on Krabbe’s division. After a brief war council, Banner took a small force consisting of the most well armed levies and all the episcopal riders with him North in order to defend his fief. His resolve was evident, for as he wrote the king: “...

My dearest gracious lord, if Your Grace has any command or dispatch for me, then Your Grace can always depend on finding me on Kalø.”

[16]

For his part, the king had remained in Hønborg, fervently trying to make sense of the confused situation. If the rebels had solely relied on conscripted peasants then the king might have been able to quell the uprising from his castles in Eastern Jutland. Unfortunately, the invasion of the ducal army had rendered the loyalist cause on the peninsula extremely fragile. The king knew full well the value and importance of the Landsknecht companies from his own Swedish campaign and had no illusion as to how long his castellans could withstand the assault of these professional soldiers. Almost all of the king’s own mercenaries had been demobilised after the capture of Stockholm: only a single

Fähnlein[17] remained in Sweden and its presence was vital for the survival of Henrik Krummedige’s viceregal government.

In order to put down the rebellion, Christian II thus needed fresh mercenaries of his own. However, the cities of Hamburg and Stade and the counties of Pinneberg and Lauenburg had all resolved to bar any mercenaries from crossing the Elbe who were not in the pay of the duke. Furthermore, before such a muster could even be completed, the Gottorpian main force would most likely had moved against Hønborg and the remaining royalist castles in Jutland. As such, the only course open to the king was to withdraw across the Little Belt to the safety of the isles. When Erik Krummedige, the fief-holder at Hønborg suggested this to Christian II, he supposedly wept before fiercely declaring that “...

as soon as the wind gave in he would do so.”

[18]

However, the king would not have to wait for the wind to give in nor would he have to sneak back across the Little Belt in a smuggler’s vessel.

Søren Norby had arrived at Copenhagen with the remnants of his battered expedition to the New World on the 24th of April. Less than a month later, he commanded the entire royal fleet as it sailed forth from the Copenhagen dockyards. Unaware of the Jutish rising fermenting on the peninsula, he had been tasked with mounting a show of force in the Fehmern Belt and thereby dissuade the Wendish Hansa from intervening in the king’s showdown with his uncle. However, on the 20th of May the fleet chanced upon a Hanseatic raiding party, headed by a handful of Lübeckian carracks and supported by auxiliary vessels from the cities of Rostock and Wismar. In a brilliantly executed interception almost the entire Wendish squadron was destroyed or captured. Faced with the realization that the realm was at war, Norby spirited on, aiming to safeguard the crossing between Jutland and Funen.

A Danish and a Hanseatic vessel exchange fire somewhere in the Baltic (the latter flying the three crowns of Sweden as a mark of provocation). From a manuscript on artillery by Rudolf van Deventer

, ca. 1582[19].

Two days after the battle, the royal fleet dropped anchor in the narrow strait between the castles of Hønborg and Hindsgavl. If the Admiral in the Eastern Sea was shocked to see his liege lord still nursing the wounds from the skirmish outside Koldinghus, the news of the councilar rebellion and the duke’s treachery positively infuriated him. Aboard the Maria, Christian II contemplated sailing the fleet South to launch a surprise attack on Lübeck itself, a notion sharply protested by his naval captains. The fortifications of Travemünde could not be easily bypassed and heavy casualties would have to be expected. Furthermore, if the navy were not present, the duke might very well attempt to seize Funen and the island’s many important castles. Although he had received the news of Gøye, Morgenstjerne and Banner’s continued fidelity with good cheer, the king was naturally suspicious of just where the rest of his fief-holders’ loyalty truly lay.

No matter how fortuitous Norby’s arrival in the Little Belt had been it did not change the military realities on the Jutish peninsula. The initiative was wholly in the hands of the duke and his mercenary army. For now, the royal navy commanded the crossing to Funen, but if the enemy were to attempt to force the straits in unison, it was by no means certain that they could be repelled. There was only one option left: Retreat and regroup. Resolving to rally the loyalist forces of the Sound Provinces, the king made preparations to leave Hønborg. In his place, Mogens Gøye was appointed stadtholder in Northern Jutland (or “

Sir King in Jutland”

[20] as the rebels derisively called him) with strict orders to defend the remaining castles for as long as possible.

On the 23rd of May 1522, Christian II commanded the fleet to head for Zealand. In the less than a fortnight which had passed since he took mass at the Franciscan Convent in Odense he had de facto lost almost half of his kingdom. In a letter to his wife on Funen, dated the following day, Tile Giseler noted that “...

His Grace’s auburn crown has in places been streamed in silver.” Everything now depended on what course of action Frederick would take.

Author's Notes: So this was a very difficult chapter to write as there were a lot of dates and a lot of characters involved. If there’s interest, I might make another intermission including a Dramatis Personae and an overview of main events incurred in the timeline so far. Let me know your thoughts.

Footnotes:

[1]From an OTL letter dated the 23rd of January 1523.

[2]The Kieler Umschlag (Kiel Exchange) was the most important market for money lending in Northern Germany and Scandinavia in the 15th and 16th centuries. It was convened annually on the 6th of January and lasted a week. In OTL, Frederick chose to participate in the conspiracy against Christian II very shortly after the Umschlag of 1523 and as such did not need to move too quietly. ITTL, however, he does not have that advantage, limiting his ability to procure funds considerably.

[3]The size of the ducal army in OTL is still rather uncertain. Some contemporary sources say the duke had 3000 peasants in his army whilst some Jutish accounts put the number slightly higher. It is, however, important to note that according to the military doctrine of the time, such levies were not considered worth much. The hired troops were the armoured fist of any army - the equivalent of modern tanks, if you will.

[4]All three were important mercenary captains during Frederick’s OTL conquest of Denmark.

[5]This also happened in OTL. The mayors of Flensburg sent a heartfelt plea for assistance to the king, promising that they would hold out for as long as possible against his uncle’s troops.

[6]The OTL designation used by the councilar opposition in their propaganda pamphlets and official declarations. The Danish phrasing is as follows: “

Danmarckis riigis raad wtij lutland besiddindis”

[7]All were signatories of the historical “conspiracy letter” wherein the signatories pledged to depose Christian II.

[8]Meaning Christian II.

[9]My own translation and transcription of a part of the mentioned “conspiracy letter.” Once again, please note how the letter uses the word “utilize” when describing the relation between the nobles and Frederick.

[10]From the OTL negotiations in April 1524 between Christian II’s ambassadors and the Gottorpian government on a possible settlement between Frederick I and his nephew. The nobility

really did not want Christian II back.

[11]In OTL, Bryske urged Christian II to burn Aalborg to the ground after its citizens went over to the rebels.

[12]From an OTL letter to Mogens Gøye dated the 17th of March 1523. Rosenkrantz belonged to the part of the nobility who was mostly loyal to the king. In OTL he joined in Mogens Gøye’s attempts at mediating between the king and the rebels, but finally renounced his loyalty to Christian II shortly after surrendering Koldinghus - supposedly out of fear of Sigbritt’s malign influence.

[13]In OTL, Aalborghus was held by a burgher fief-holder. ITTL, Christian II granted it to Henrik Gøye, but his capture outside Koldinghus led to a power vacuum within the city, easily exploited by the rebels.

[14]The hundreds of Onsild, Nørre Hald and Støvring were amalgamated into a pledge-fief under Ove Bille, royal chancellor and bishop of Aarhus.

[15]Besides being rich and progressive for the times, Mogens Gøye was highly respected by commoners and nobles alike. During the Count’s Feud he was one of the few aristocrats who could soothe the enraged peasantry when they went about killing noblemen and torching manors. ITTL, the capture of his brother and the king’s much more amiable disposition puts him solidly in the royal camp.

[16]From an OTL letter dated the 27th of January 1523.

[17]A military unit of some 500 troops.

[18]This might be apocryphal as it was only mentioned by Frederick I’s chancellor Wolfgang von Utenhof some 15 years after the rebellion. Nevertheless, it is a famous remark which many historians have seen as a summary of Christian II’s OTL mercurial reign. One of the most important pieces of literature on the events of 1523 even bears its name.

[19]Originally the drawing depicts a naval action during the Northern Seven Years War.

[20]This was originally a remark Gøye attributed to Sigbrit and one of the reasons he gave for renouncing his allegiance to Christian II in OTL.