So, Calbear's amazing Anglo-American/Nazi war timeline is over, and I now no longer have Saturdays to look forward to. As a long-time lurker, few-time poster, I've decided to give back to the community.

As you may know, I've been running a very in-depth simulation of the Space Race for nine years. Every year, I gather ten players together (five Russian, five Americans) and model national civilian and military space programs one semi-annum at a time. Since 2002, I have run the game ten times, and we've gotten through 1973.

Each individual session has involved hundreds of hours of research and preparation. It is possibly the most obsessive role-playing game ever.

I'm going to post a narrative of this alternate Space Race in weekly bits. Since the story is set (like Calbear's was), I welcome your comments and criticisms, but I can't really change events. You'll just have to deal with the timeline, even in the implausible bits. I don't think anything is ASB.

By the by, I am a space historian in real life. You can see my scholarly, published works at http://www.sdfo.org/stl. I've got a new article coming out in Quest, Space Quarterly shortly.

Without further ado...

---

(Sputnik 1, launched October 4, 1957)

A History of "The Space Race," Part 1

The International Geophysical Year (IGY), 1957-1958

[Prelude]

On October 4, 1957, the Soviets made history with the launching of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1 atop the world's first ICBM, the R-7. Though not completely unexpected, it did cause the Americans to compress the timetable of its civilian launch program, Vanguard. The Vanguard rocket was far less powerful than any Soviet booster, and its payload correspondingly tiny. Thus, Wernher von Braun's team in Huntsville, employing a derivative of the Redstone IRBM dubbed Jupiter-C, was tasked with the job of serving as back-up to the unreliable Vanguard program. Such foresight proved wise. When the October 23 and December 6 Vanguard launches ended in fiery failure, Wernher von Braun's team was ready to launch, and on January 1, 1958, America's first artificial satellite, Explorer I, soared into orbit. Explorer orbited for a full 113 days and returned exciting data about a region of charged particles trapped around the Earth latter named the "Van Allen" belt.

[The First Probes]

The Soviets did not remain idle. On March 18, 1958, using an improved version of the R-7, Sputnik 2 was propelled into orbit. It weighed a ton and a half and was an unprecedentedly complex physical laboratory. Though trumped by Explorer I in the discovery of the Van Allen belts, Sputnik 2 had the instrumentation required to map them. A second large Sputnik was orbited on May 15. International newspapers gushed over the superiority of Communist science and lampooned the Americans for their tiny efforts.

The Army's Explorer series proved robust, however. Despite a failed launch on March 1, 1958, Explorer III flew without a hitch on the 26th. Explorer IV did not fly until July 26 with Explorer V following soon after on August 24. Both provided valuable data on high altitude nuclear tests. Explorer VI, launched atop the Jupiter-derived Juno II booster, represented the last of the Army payloads, but was destroyed along with its carrier only a few seconds after liftoff. Any future scientific satellites would be flown under the auspices of the newly created civilian National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Meanwhile, the Vanguard program continued apace suffering further explosive setbacks on February 5, March 17, and April 28. It was not until May 27 that Vanguard I finally arrived in orbit. The tiny satellite avoided historical oblivion through its geodetic discovery that the Earth sported a pear-shaped deviation from its expected smooth oblate shape. Vanguard 2 followed on June 26, providing excellent data on the reflectivity of the Earth's atmosphere. The IGY would see no more successful Vanguard launches with the launch on September 26 ending in an improper stage separation. The program would continue into 1959, however.

[To the Moon]

On October 1, 1958, President Eisenhower signed into existence the National Aeronautics and Space Administration whose function would be to oversee all civilian manned and unmanned space programs. Their first project, though still officially under the auspices of the Army, was a lunar flyby series. Utilizing the Juno II, the tiny spaceship was dubbed "Elaine I" in accordance with the new naming scheme which employed Norse mythology. The first Elaine became the first craft to fly past the moon on August 19, 1958. Approaching within 26,328km, this probe discovered the complete lack of a lunar magnetic field.

(launch of Elaine 1, August 19, 1958)

Beaten to the punch, the Soviets nevertheless sent a much large spacecraft on September 23 (using a further modified R-7) to fly just under 6000km above the Moon's surface. Though it was considered a tremendous feat of navigation at the time, recently recovered documents indicate that "Lunastrela 1" in fact *missed* the moon and was intended to be an impactor mission. Lunastrela 2, an identical craft, did hit the moon on October 12 scattering Soviet pendants across the lunar surface. Close on its heels, on October 13, Elaine 2 duplicated her sister's feat, flying by the moon at a distance of 23,817km.

The American lunar follow up was to be a series of small lunar orbiters employing the new Atlas ICBM coupled with the second stage of the Vanguard rocket. Few were hopeful about the marriage of two unreliable booster systems. The project was begun on July 12, 1958 and dubbed Valkyrie. If possible, it was hoped that a mission could be reserved for the first interplanetary jaunt--to Venus. Around the same time, the Soviets began construction of a lunar flyaround designed to photograph the back side of the moon.

[The Military]

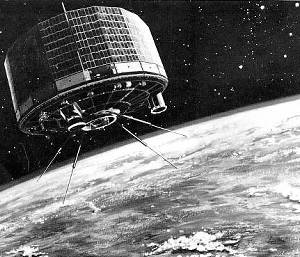

The battle for a dominant role in communications ended swiftly and amicably. The military was given control of active satellites and NASA oversight of passive satellites. The first military comsat, Project Achilles, failed to orbit on December 18, 1958. Other DoD projects included an early warning satellite detection system and, working with the CIA, a satellite reconnaissance system. The latter took on heightened importance after the shooting down of an American U2 spyplane over the Soviet Union in January of 1958 which resulted in a shut down of all aerial overflights of Russia. The spy satellite project, dubbed Discoverer, was begun on February 2, 1958.

[Soviet machinations]

The Soviets put a lower priority on satellite reconnaissance. Khruschev had a vision of the importance of manned space flight, and he dreamed of cosmonauts treading the vast expanses of space and the foreign soils of other planets far ahead of any American pretenders. In this climate, the architect of the Soviet space program, head of OKB-1, Sergei Korolev, found no difficulty in securing resources to launch the first manned spaceship, called Nievo. The Nievo project was begun in December of 1958. The Soviet spy satellite version, entitled Otkrivat, would languish as the military, and its patrons Ustinov and Suslov, angrily fumed.

Mikhail Yangel's head of the space megacomplex, OKB-586, had a more practical goal. He had just completed flight tests of the R-12 IRBM, scheduled to enter service in 1959. Though the bureau was kept busy as it developed the R-16 next generation ICBM and the R-14 MRBM, Yangel sought and won approval to modify the R-12 to serve as a satellite booster. Of course, the R-12 could only launch small payloads, being roughly equivalent to the American Jupiter. Thus, Yangel was forced to embark on a difficult but ultimately successful program to develop miniaturized components for small satellites. Both the rocket and satellite programs were begun in early 1958.

Hypersonic jet pioneer Vladimir Chelomei of OKB-52, the third leg of the Chief Designer triad, was a virtual unknown in 1957. All this changed when he scored a political coup and hired Sergei Khruschev, son of the Premier, in early 1958. As a result, early 1959 would find Chelomei with three new bureaus under his command, enabling him to pursue a variety of dreams. 1958 was spent primarily in the completion of draft projects and work on the M-50 supersonic bomber.

[Toward an American in Space]

Early 1958 saw a whirlwind of proposals for the first American manned spacecraft. By the second half of the year, three emerged as viable opponents, each securing funding. The first was the minimalist Man In Space Soonest (MISS) USAF program, canceled within a few months of its initiation. The second was a zero-lift capsule civilian project scheduled for orbital launches in 1961. It was appropriately named "Magellan." A top secret third project involved a highly modified version of the X-15 experimental spaceplane. Three X-15s were delivered in October of 1958 for flight tests. The ultimate plan involved mating the specialized X-15b with three Navaho cruise missile boosters to send a man around the Earth once. This risky project was green lighted as a hedge against possible Magellan delays. Though the mission was originally designed to end with the pilot ditching the spaceplane into the Gulf of Mexico, it was eventually decided that the pilot should land the plane both for publicity and engineering reasons.

[A Year (and a half) of Accomplishments]

In the end, the IGY saw a flurry of space activities motivated by a competitive spirit between the two superpowers. Both sides were now poised to seize the high ground for both scientific and military purposes...

As you may know, I've been running a very in-depth simulation of the Space Race for nine years. Every year, I gather ten players together (five Russian, five Americans) and model national civilian and military space programs one semi-annum at a time. Since 2002, I have run the game ten times, and we've gotten through 1973.

Each individual session has involved hundreds of hours of research and preparation. It is possibly the most obsessive role-playing game ever.

I'm going to post a narrative of this alternate Space Race in weekly bits. Since the story is set (like Calbear's was), I welcome your comments and criticisms, but I can't really change events. You'll just have to deal with the timeline, even in the implausible bits. I don't think anything is ASB.

By the by, I am a space historian in real life. You can see my scholarly, published works at http://www.sdfo.org/stl. I've got a new article coming out in Quest, Space Quarterly shortly.

Without further ado...

---

(Sputnik 1, launched October 4, 1957)

A History of "The Space Race," Part 1

The International Geophysical Year (IGY), 1957-1958

[Prelude]

On October 4, 1957, the Soviets made history with the launching of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1 atop the world's first ICBM, the R-7. Though not completely unexpected, it did cause the Americans to compress the timetable of its civilian launch program, Vanguard. The Vanguard rocket was far less powerful than any Soviet booster, and its payload correspondingly tiny. Thus, Wernher von Braun's team in Huntsville, employing a derivative of the Redstone IRBM dubbed Jupiter-C, was tasked with the job of serving as back-up to the unreliable Vanguard program. Such foresight proved wise. When the October 23 and December 6 Vanguard launches ended in fiery failure, Wernher von Braun's team was ready to launch, and on January 1, 1958, America's first artificial satellite, Explorer I, soared into orbit. Explorer orbited for a full 113 days and returned exciting data about a region of charged particles trapped around the Earth latter named the "Van Allen" belt.

[The First Probes]

The Soviets did not remain idle. On March 18, 1958, using an improved version of the R-7, Sputnik 2 was propelled into orbit. It weighed a ton and a half and was an unprecedentedly complex physical laboratory. Though trumped by Explorer I in the discovery of the Van Allen belts, Sputnik 2 had the instrumentation required to map them. A second large Sputnik was orbited on May 15. International newspapers gushed over the superiority of Communist science and lampooned the Americans for their tiny efforts.

The Army's Explorer series proved robust, however. Despite a failed launch on March 1, 1958, Explorer III flew without a hitch on the 26th. Explorer IV did not fly until July 26 with Explorer V following soon after on August 24. Both provided valuable data on high altitude nuclear tests. Explorer VI, launched atop the Jupiter-derived Juno II booster, represented the last of the Army payloads, but was destroyed along with its carrier only a few seconds after liftoff. Any future scientific satellites would be flown under the auspices of the newly created civilian National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Meanwhile, the Vanguard program continued apace suffering further explosive setbacks on February 5, March 17, and April 28. It was not until May 27 that Vanguard I finally arrived in orbit. The tiny satellite avoided historical oblivion through its geodetic discovery that the Earth sported a pear-shaped deviation from its expected smooth oblate shape. Vanguard 2 followed on June 26, providing excellent data on the reflectivity of the Earth's atmosphere. The IGY would see no more successful Vanguard launches with the launch on September 26 ending in an improper stage separation. The program would continue into 1959, however.

[To the Moon]

On October 1, 1958, President Eisenhower signed into existence the National Aeronautics and Space Administration whose function would be to oversee all civilian manned and unmanned space programs. Their first project, though still officially under the auspices of the Army, was a lunar flyby series. Utilizing the Juno II, the tiny spaceship was dubbed "Elaine I" in accordance with the new naming scheme which employed Norse mythology. The first Elaine became the first craft to fly past the moon on August 19, 1958. Approaching within 26,328km, this probe discovered the complete lack of a lunar magnetic field.

(launch of Elaine 1, August 19, 1958)

Beaten to the punch, the Soviets nevertheless sent a much large spacecraft on September 23 (using a further modified R-7) to fly just under 6000km above the Moon's surface. Though it was considered a tremendous feat of navigation at the time, recently recovered documents indicate that "Lunastrela 1" in fact *missed* the moon and was intended to be an impactor mission. Lunastrela 2, an identical craft, did hit the moon on October 12 scattering Soviet pendants across the lunar surface. Close on its heels, on October 13, Elaine 2 duplicated her sister's feat, flying by the moon at a distance of 23,817km.

The American lunar follow up was to be a series of small lunar orbiters employing the new Atlas ICBM coupled with the second stage of the Vanguard rocket. Few were hopeful about the marriage of two unreliable booster systems. The project was begun on July 12, 1958 and dubbed Valkyrie. If possible, it was hoped that a mission could be reserved for the first interplanetary jaunt--to Venus. Around the same time, the Soviets began construction of a lunar flyaround designed to photograph the back side of the moon.

[The Military]

The battle for a dominant role in communications ended swiftly and amicably. The military was given control of active satellites and NASA oversight of passive satellites. The first military comsat, Project Achilles, failed to orbit on December 18, 1958. Other DoD projects included an early warning satellite detection system and, working with the CIA, a satellite reconnaissance system. The latter took on heightened importance after the shooting down of an American U2 spyplane over the Soviet Union in January of 1958 which resulted in a shut down of all aerial overflights of Russia. The spy satellite project, dubbed Discoverer, was begun on February 2, 1958.

[Soviet machinations]

The Soviets put a lower priority on satellite reconnaissance. Khruschev had a vision of the importance of manned space flight, and he dreamed of cosmonauts treading the vast expanses of space and the foreign soils of other planets far ahead of any American pretenders. In this climate, the architect of the Soviet space program, head of OKB-1, Sergei Korolev, found no difficulty in securing resources to launch the first manned spaceship, called Nievo. The Nievo project was begun in December of 1958. The Soviet spy satellite version, entitled Otkrivat, would languish as the military, and its patrons Ustinov and Suslov, angrily fumed.

Mikhail Yangel's head of the space megacomplex, OKB-586, had a more practical goal. He had just completed flight tests of the R-12 IRBM, scheduled to enter service in 1959. Though the bureau was kept busy as it developed the R-16 next generation ICBM and the R-14 MRBM, Yangel sought and won approval to modify the R-12 to serve as a satellite booster. Of course, the R-12 could only launch small payloads, being roughly equivalent to the American Jupiter. Thus, Yangel was forced to embark on a difficult but ultimately successful program to develop miniaturized components for small satellites. Both the rocket and satellite programs were begun in early 1958.

Hypersonic jet pioneer Vladimir Chelomei of OKB-52, the third leg of the Chief Designer triad, was a virtual unknown in 1957. All this changed when he scored a political coup and hired Sergei Khruschev, son of the Premier, in early 1958. As a result, early 1959 would find Chelomei with three new bureaus under his command, enabling him to pursue a variety of dreams. 1958 was spent primarily in the completion of draft projects and work on the M-50 supersonic bomber.

[Toward an American in Space]

Early 1958 saw a whirlwind of proposals for the first American manned spacecraft. By the second half of the year, three emerged as viable opponents, each securing funding. The first was the minimalist Man In Space Soonest (MISS) USAF program, canceled within a few months of its initiation. The second was a zero-lift capsule civilian project scheduled for orbital launches in 1961. It was appropriately named "Magellan." A top secret third project involved a highly modified version of the X-15 experimental spaceplane. Three X-15s were delivered in October of 1958 for flight tests. The ultimate plan involved mating the specialized X-15b with three Navaho cruise missile boosters to send a man around the Earth once. This risky project was green lighted as a hedge against possible Magellan delays. Though the mission was originally designed to end with the pilot ditching the spaceplane into the Gulf of Mexico, it was eventually decided that the pilot should land the plane both for publicity and engineering reasons.

[A Year (and a half) of Accomplishments]

In the end, the IGY saw a flurry of space activities motivated by a competitive spirit between the two superpowers. Both sides were now poised to seize the high ground for both scientific and military purposes...

Last edited: