United States presidential election, 1976: The Primaries

One of the favorite “what-if” moments of amateur historians is this: What if Scoop Jackson had decided to compete in Iowa and New Hampshire? In retrospect, the importance of the new delegate system put in place by the Democratic party is obvious – no longer would party bosses award the nomination, but it would be decided in dozens of contests across the country by the voters, who chose a large majority of the delegates. Jackson excelled at retail politics and would have gone over in the grip-and-grin capitals of American politics. But he had a long career as a party statesman and a good relationship with bosses across the country, and accordingly chose to concentrate his early efforts in machine states.

The Iowa caucuses provided few answer for either side. On the Democratic side, “Uncomitted” drew 35%, easily besting Jimmy Carter and and Birch Bayh, who dominated the conservative and liberal vote and essentially tied at 20% and 18%, respectively. Udall, another liberal, was fourth with 6%. Carter’s strategy at the time was daring – he planned to compete in every single primary and caucus, alone among all the candidates. But this strategy was expensive and all-consuming, and depended on drawing early momentum to generate media attention for the big states that would come later. At the time the Iowa caucuses were a poor relation to the New Hampshire primary, and Carter’s “victory” went little-noticed.

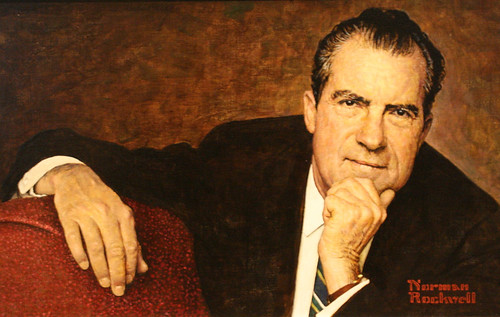

On the Republican side, Ronald Reagan squeezed out a narrow victory over Vice-President Ford, the liberal Senator Nelson Rockefeller of New York, and John Connally, 30-28-25-17. Perennial candidate Harold Stassen of Minnesota won no delegates. Rockefeller had the dwindling liberal Republican base all to himself, but was essentially doomed even before he began, leaving Reagan, Ford, and Connally to fight it out. Despite his victory, Reagan’s hopes were bleak – Ford had the party machinery on his side, and most of the early states were in the east, far from Reagan’s California base.

New Hampshire attracted far more attention. Congressman Udall squeaked out a surprise victory, with Carter once again in second. Bayh was a distant third, and already considering dropping out. The GOP side featured a shocker as well, as Rockefeller topped Reagan and Ford by a healthy margin, as the conservatives split the vote. Conally came in last again, and began to see Florida a few weeks away as his last stand.

March 2 hosted a pair of New England contests, as voters in Massachusetts and Vermont went to the polls. Jackson’s support from the Boston machine paid off, as he won in MA easily. But Sargent Shriver managed to prop up his tottering campaign by besting Carter in Vermont. Ford came roaring back and won both states handily, with Reagan once again placing third. A two-week stretch which featured delegate-rich Florida, Illinois, and North Carolina loomed, and four different candidates could now boast of having won four different contests on the Democratic side, while Reagan and Ford were evenly split. Jimmy Carter was justifiably tearing his hair out. He had come in second in every contest, and had won more votes and more delegates than any other candidate. But he was always a bridesmaid and never a bride, and the money and media attention continued to flow elsewhere.

His frustration would mount: George Wallace narrowly won Florida, the first state in which he would compete, which Carter – once again – in second. Scoop Jackson came in third and turned his attention to New York and Pennsylvania, two and four weeks away. Bayh won 1% and dropped out of the race, boosting Udall and Shriver. Ford scored a healthy victory over a divided conservative field, and third-place finisher Connally ended his campaign. The pendulum swung back to Ford in Illinois, where Reagan placed third, but Rockefeller’s fundraising was dwindling and needed a big victory in his home state of New York on April 6. Illinois only confused the Democratic field further – Carter finally won a state, but by a margin of only 1% over George Wallace, with Shriver close behind. (Jackson, curiously, had chosen not to compete in Illinois, perhaps guessing that too many conservative candidates would split the vote of white Democrats.) Carter’s elation was short-lived, as Wallace took North Carolina by an identical margin a week later. Reagan, with Connally out of the way, triumphed in that state, where Rockefeller’s decision to get on the ballot probably drew votes from Ford.

April 6 dawned, the most important day yet, as Wisconsin and New York voters would go to the ballot box. The GOP side offered no surprises, as Rockefeller took his home state easily and was blown out of the water in Wisconsin, where Ford bested Reagan narrowly. Jackson, as expected, used his familiarity with NYC bosses to win the state (Carter had unwisely spoken against “special favors” for the Big Apple, which sounded suspiciously like he would have refused to bail the city out the year before.) Carter placed second yet again in Wisconsin, finishing behind a resurgent Udall.

Despite his failure to break through, Carter still led in delegates, while Jackson led in the polls. The liberal wing of the Democratic party was faced with two conservative front-runners. Jerry Brown in California had grown concerned at the race's direction, and had jumped in himself in March. but to filing deadlines, he would not appear on a ballot until May 4, in Georgia, where he hoped that Carter and Wallace and would split the vote. In the meantime, Jackson's inside baseball politics won him Pennsylvania, with Udall and Carter a few thousand votes behind. Ford bested Reagan in the state easily. In Texas, favorite son Lloyd Bentsen ran away with the Democratic primary, beating Carter by over ten points. Reagan, who had appeared on the ropes after three straight losses, revived his campaign with a strong victory there.

Reagan now went on a run, winning both Georgia and Indiana on May 4, and Nebraska a week later (he nearly beat Ford in West Virginia the same day). Rockefeller dropped out of the race in early May, which was expected to give a bit of breathing room to the moderate Ford. In practice, Rockefeller Republicans generally sat on their hands for the rest of the primary season. Carter finally scored another victory in his home state of Georgia, where only Wallace and Brown had chosen to compete. That same day, he had to watch Jackson take Indiana, however, while Mo Udall took the liberal stronghold of Washington DC. Favorite son Robert Byrd took West Virginia, Frank Church won in Nebraska, Sargent Shriver dropped out, and the race became even more muddled.