You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Help Wanted: Seeking Emperor - Bonaparte Mexico

- Thread starter Lord Atlas

- Start date

-

- Tags

- bonaparte mexican empire

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 34 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter XXIV: The United States, 1836-1844 Chapter XXV: The United States, 1844-1848 Chapter XXVI: Defending the Northwestern Mexican Frontier Chapter XXVII: The Great Game Begins Chapter XXVIII: The Early Zenaiden Empire Chapter XXIX: Mexican Misadventures in the Far East Chapter XXX: Mexican Culture during the Early Zenaiden Age Chapter XXXI: European Crises of the Late 1840sPharaonist Egypt, anyone?

I could see that with a rise in the use of the Coptic lanugage along with Coptic Christianity. Granted, they'd have to make sure not to isolate their Muslim peers for that (the same for Morocco and their Berbers.)

I wonder how annoyed the rest of the Amphicytons were with the US regarding the incident with Hawaii. Meanwhile, oh Brazil... why do you always tend to do this?

For some reason, I can see Andalusia and Morocco get into a personal union... meanwhile, I have a feeling Morocco and Egypt would bond because of their pride over their pre-Islamic cultures (in the same way Mexico and Peru have special relationships over their pre-Columbian civilizations.)

Looks like Castile and Aragorn have still learned nothing. Meanwhile, Sweden joining the League is pretty interesting.

Overall, a very fascinating update. Hawaii as a sovereign nation is itneresting and I could see them lasting longer with Mexican support.

The Amphictyons are willing to put up with a lot from the USA because of its money and size (one of the informal requirements for being ambassador to the US is being phenotypically white, for instance), but if the US expand into the Caribbean or South America the Amphictyons will probably demand that they not expand slavery, with Mexico and Colombia leading the charge. Not having these outlets for new slave states might put more pressure on US Congress to pass TTL Kansas-Nebraska Act.

Northern and Northeastern Africa might be better off TTL with vast empires like Morocco, Egypt, and even Ethiopia carving out their corners of the continent and centralizing power. If the Amphictyons wage war against the Hegemons, I feel like taking South Africa would be strategically valuable to prevent the British from moving troops and supplies to and from the Far East, so South Africa could be in for a shock. Possibly an alliance with the Boer states? (I've also been tossing around an idea for Chilean New Zealand, but I'm still on the fence for that one, it's mostly just a fun thought.)

Castile and Aragon are an example of Machiavelli's line "Men sooner forget the death of their father than the loss of their patrimony." This time Andalusia will probably be given huge chunks of territory to permanently end their threat.

Having Sweden attempt to join the Amphictyons will probably have fun consequences: like maybe Sweden gets involved in the Scramble for Africa in place of Belgium or sends troops to fight for the Union during the Civil War. More seriously, it can set a precedent for non-American countries to join, like the Philippines, Korea, Japan or China, or any countries that pop out of colonies in India. Fun times.

Pharaonist Egypt, anyone?

Egyptian Arabic will probably have more Coptic loan words, and a different cultural identity as a result of the inevitable clash with the Ottomans will probably. Plus, it could heal divides between Christians and Muslims, but I doubt any mass conversions will happen.

Still, there could also be a Mediterranean-focused cultural movement on an international scale, seeing as most of the Bonapartist countries are on the Mediterranean and have a lot of interlocking history. At this point, the Bonapartists alliance is like an Ancient Roman reunion, now with civilized barbarians! TTL propagandists would not be strapped for material.

The Amphictyons are willing to put up with a lot from the USA because of its money and size (one of the informal requirements for being ambassador to the US is being phenotypically white, for instance), but if the US expand into the Caribbean or South America the Amphictyons will probably demand that they not expand slavery, with Mexico and Colombia leading the charge. Not having these outlets for new slave states might put more pressure on US Congress to pass TTL Kansas-Nebraska Act.

Northern and Northeastern Africa might be better off TTL with vast empires like Morocco, Egypt, and even Ethiopia carving out their corners of the continent and centralizing power. If the Amphictyons wage war against the Hegemons, I feel like taking South Africa would be strategically valuable to prevent the British from moving troops and supplies to and from the Far East, so South Africa could be in for a shock. Possibly an alliance with the Boer states? (I've also been tossing around an idea for Chilean New Zealand, but I'm still on the fence for that one, it's mostly just a fun thought.)

Castile and Aragon are an example of Machiavelli's line "Men sooner forget the death of their father than the loss of their patrimony." This time Andalusia will probably be given huge chunks of territory to permanently end their threat.

Having Sweden attempt to join the Amphictyons will probably have fun consequences: like maybe Sweden gets involved in the Scramble for Africa in place of Belgium or sends troops to fight for the Union during the Civil War. More seriously, it can set a precedent for non-American countries to join, like the Philippines, Korea, Japan or China, or any countries that pop out of colonies in India. Fun times.

Egyptian Arabic will probably have more Coptic loan words, and a different cultural identity as a result of the inevitable clash with the Ottomans will probably. Plus, it could heal divides between Christians and Muslims, but I doubt any mass conversions will happen.

Still, there could also be a Mediterranean-focused cultural movement on an international scale, seeing as most of the Bonapartist countries are on the Mediterranean and have a lot of interlocking history. At this point, the Bonapartists alliance is like an Ancient Roman reunion, now with civilized barbarians! TTL propagandists would not be strapped for material.

I could definitely see the USA issue, but it would definitely raise the stakes regarding racism and slavery in the USA, probably more so than in OTL since these political snafus have consequences that cannot be ignored.

Definiely makes sense for Morocco, Egypt and Ethiopia to do better and centralizing power. South Africa would be an odd one, though maybe the various South African peoples (Zulus, Xhosa, etc) could have their own little nation and just have good relations with the Amphicytons.

So Castile and Aragon need another lesson in humility. Right on. Morocco may want the chance to help out Andalusia and slowly get their "old partner" back with them if you will. Something like how Austria-Hungary is in a sense.

Scramble for Africa will be interesting to see though given how Mexico will have the best relationship, maybe more will note how their model of just a business relationship and not cultural dominance would work better. Regarding Africa, it's all about how they could get there. Any post-British Indian nation would have the best chance of making a colony while I could see Ethiopia maybe trying to spread more Christianity to Eastern Africa through indirect means (church helping build infrastructure and so on.)

I don't see any mass conversions happening, but I could see a greater Coptic Christian population in Egypt and perhaps enough so Coptic and Egyptian Arabic to become the dual official languages. Especially since the Arab populations don't have that good relations with their African counterparts and Egypt refuses to be the exception because of their glorious past in Africa and in the founding of civilization. I could definitely see the Mediterreaneans giving the money to the Coptic groups for that. Harder to say for Morocco given the Afro-Arab dominance over the Berbers, but maybe the various Berber groups there would try and make a deal. Granted, it could just be more representation and better living conditions and what not.

I like the idea. Plus it seems to be a move that the Khedives would make in order to strengthen ties with their Bonapartist allies. And the christian elements in the Bonapartist league would approve and want to back Egypt up if war came as they would see it as defending Christians that would be better off under the Egyptian rule than that of Ottoman rule.Pharaonist Egypt, anyone?

Chapter XXVIII: The Early Zenaiden Empire

The Zenadien Age, 1844-1858

Domestic Policy

Mexican Catholic Church

Following the Reactionary Revolt and the mass purging of reactionary bishops (and the occasional innocently conservative bishop), including the Archbishop of Mexico City, the Catholic Church in Mexico was in a weird spot. The long conclave and ensuing war between Catholic powers that saw Pope Julius IV flee Rome also prevented much in the way of resolution, so Emperor José, acting in the interest of the Church and in his position of defender of the Catholic faith in Mexico, started appointing bishops and priests from the laity (even a few dozen nuns) and priory schools who agreed with a roughly Christian humanist outlook or were just docile in political matters.

The goal was ultimately to keep the basic church infrastructure running, but the blatant caesaropapism made pro-Church intellectuals and politicians really nervous. If it weren’t for the circumstances leading to a loss of legitimacy for the Church and the Mexican populace wanting a quick return to normalcy after the Revolt, the powergrab probably would have lead to riots. Plus the Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs had the sense to make sure that as many as the replacements as possible had some existing connection to or approval from the community, so it was an easier pill to swallow.

The government’s appointment of bishops during this period almost masked the fact that the government was widely confiscating Church lands and arresting pro-Church newspapermen and publishers. The land was either sold to the people working the land if they supported the government or transferred to the state government as a reward for loyalty. This may have contributed to the Panic of 1847 in Mexico as farmers couldn’t pay back loans on land and equipment and there was a general fear for property rights. Most of the publishers were eventually released by the Senate Board of Freedom of the Press, but their equipment and offices had long since been seized, stolen, or lost, and the government refused to recompense them.

The message was clear: “Stay in line or be crushed.”

Still, events might have played out differently if it weren’t for the election of pro-Bonapartist Cardinal Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti as Pope Martin VI¹ in 1846. Pope Martin legitimized the appointments made by Emperor José and negotiations were begun during the first year of Empress Zenaida’s reign to see if the Catholic Church in Mexico could be given sui iuris full communion with the Papacy like the Eastern Catholic Church.

These negotiations, largely personally between Pope Martin VI and Emperor Luciano I² bore fruit in 1849 with the Glorious Reform (or Glorious Concordat). The Archbishop of Mexico City was given full authority over nominations and promotions within the Mexican Catholic Church, but the Archbishop had to be nominated by the pope and approved by the Emperor/Empress. Likewise, the Mexican Church was given the authority to bless Mexican individuals in a unique beatification ceremony as it saw fit and maintain its own traditions.

To celebrate, Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, the famed Native Mexican who saw apparitions of the Virgin Mary at Tepeyac Hill and received the famous tilma with her appearance, was beatified on Christmas Day 1849, and the first mass entirely in the vernacular was held at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe on New Year’s Day 1850, with the royal family in attendance.

These innovations actually worked in bringing back popular confidence in the Church as an instrument of public good and a worthwhile Mexican institution, and the new preachers found willing flocks to hear state-friendly sermons. Still, the Church remained influential, if different. For example, most of the radical interventionalists who pushed for war with the United States to free the slaves were preachers and their flocks.

In 1853, the Archbishop of Mexico City declared that the Mexican Catholic Church would recognize marriage between slaves. This, and Pope Martin VI’s declaration that owning Christians was a grave sin, resulted in the burning of several Catholic Churches in the Southern United States, restrictions on black participation in Catholic mass, conversions of several slaveholders to some form of Protestantism, and Cubans selling their plantations and slaves to absentee owners (absentee plantations in the Yankee Caribbean were worse than average; the overseers didn’t care if the owner had to spend money on a new slave). While the Archbishop’s naive plan to make the lives of slaves easier (“Surely, they wouldn’t separate lawfully recognized families, would they? Plus it would make the slaves so happy.”) backfired, Mexicans were outraged at the treatment of the Church by pro-slavery forces.

The Birth of Labor & the Death of Debt Peonage

Juan Álvarez; Prime Minister of Mexico, 1848-1855

Before the outbreak of the California Gold Rush, the Mexican Empire was on a bimetallic (gold and silver) currency, but the mass influx of gold rose the relative price of silver and increased the money supply, meaning that inflation and a monetary supply shock were concerns. In order to stabilize the economy, Liberal leadership under Prime Minister Álvarez and Conservative leadership under Deputy José Ignacio Pavón settled on an agreement to switch the country to a pure gold standard.

Two factions within the Liberal Party, the Reformers and Worker’s Men, however, opposed the plan and managed to halt the process. They wanted to improve the lives of poor farm workers, disproportionately Native Americans, who were caught in the system of debt peonage; their argument was that inflation was a good thing as it made the debts that the poor owed to their landlords worth less and easier to pay off. These men were under the leadership of a Zapotec man from the state of Oaxaca called Benito Juárez.

Talks between the “elitists” and “anarchists” collapsed, and the threat of another panic loomed at the capital. Empress Zenaida, in the imperial role of mediator, called on the party leadership and factional leaderships for the workers, industrialists, and landowners to meet with her and her full ministry to settle the dispute. If they refused, she would dissolve the Chamber of Deputies and hold new elections when it was clear someone would win a majority.

The result was the Compromise of 1853. The country was set to transition to the gold standard, but the plight of the debt peons would be addressed in what became known as the “Peon Bill of Rights” (“Carta de Derechos del Peón”). The main points are as follows:

The final vote was 115-105 in favor, with certain industrialists and merchants being the surprise allies to labor in this instance. Industrialists figured that free peons moving to the urban centers and factories would lower wages in general, and the merchants hoped that direct access to the peons would mean better prices. (They knew, for instance, that a landowner could buy equipment for say 350 pesos and then sell it to the laborers for 450. Now, the merchants could sell it directly to the peons for 400, thus making a larger profit and being a good guy to the new customer.) Both also liked the chance to challenge the power and influence of the large landowners and secure a stable currency. Naturally, they refused to accept that the act applied to industrial workers and did everything in their power to prevent it, successfully.

This move solidified Mexico’s growing reputation as “the Liberal Empire” and led to the first recorded instance of Empress Zenaida’s popular nickname “La Gran Dama” (“The Great Lady”) among the working classes who increasingly saw her as their champion. For Juárez, it met a brief stint as Minister of Indian Affairs (1854-1855) and national press that could hopefully help his push to the premiership.

The elections the following year did, however, show a slight move away from radical reform as moderates and Conservatives took the premiership under Rómulo Díaz de la Vega.

Rómulo Díaz de la Vega; Prime Minister of Mexico, 1855-1859

Foreign Policy

The Treaty of Kingston (1846)

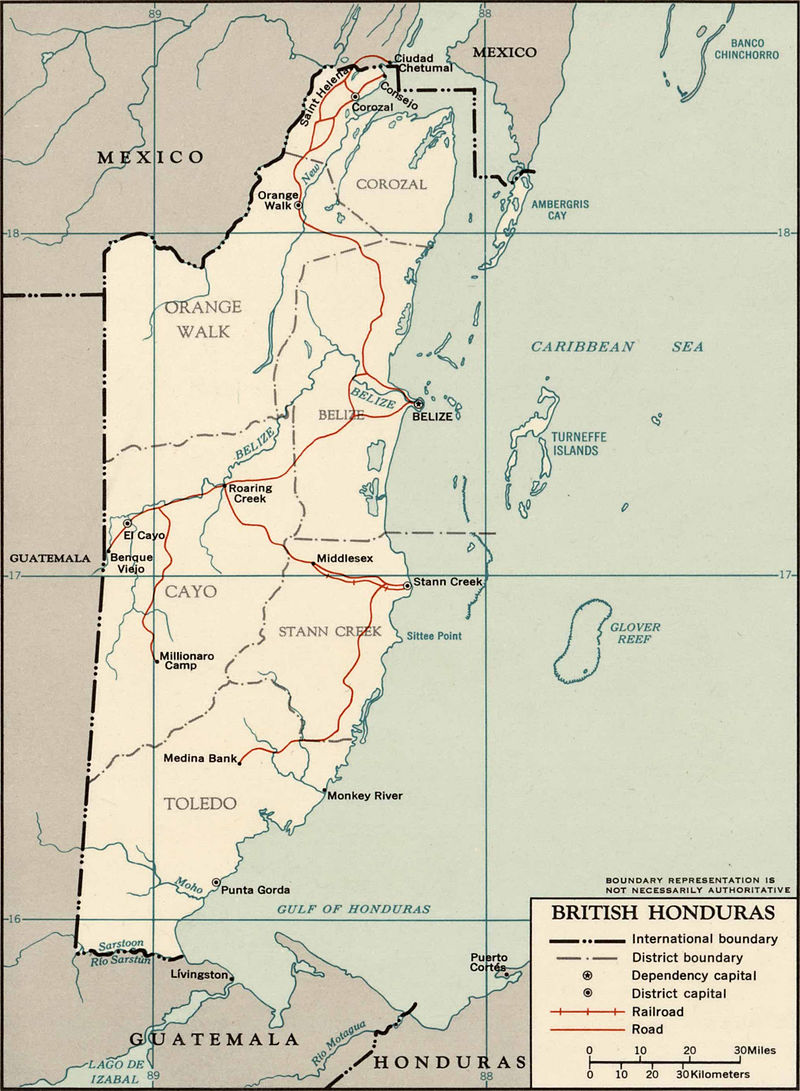

In her coronation speech, Empress Zenaida claimed that she wasn’t a puppet of Rome, and Britain was willing to test her by attempting to negotiate a firm border for British Honduras. Foreign Ministers José Joaquín de Herrera and the Viscount Palmerston negotiated by proxy in Kingston, Jamaica, and the Treaty of Treaty was ratified by the British Parliament and Mexican Assembly on 23 April 1846.

Mosquito Bay was recognized as Mexican territory, British Honduras was recognized as British territory to be renamed “Belize” to distinguish it clearly from the Mexican territory of Honduras, Belize would be given full free-trade access to Mexican markets and vice versa, Belize would be given a local, democratically-elected parliament with limited powers over domestic, Mayan, affairs, and a railroad would be constructed between Belize City and Guatemala City.

Dominican Revolution of 1850

On 9 July 1850, President Jean-Pierre Boyer of Haiti died, triggering a succession crisis. General Faustin Soulouque called for new elections, but Vice-President Jean-Louis Pierrot (the de jure president) claimed that there was no need. General Soulouque led his troops into open rebellion calling for new elections and a greater democratization of the country.

In the eastern, former Spanish part of the island, the Dominicans, under the leadership of Pedro Santana y Familias and Juan Pablo Duarte. Santana, however, figured that Santo Domingo, with a smaller population and questionable economical prospects, would constantly struggle and would be better off annexed by a larger power. He tried to sell his fellow revolutionaries on the idea that the Dominicans should seek annexation by Mexico, a plan generally supported by conservatives and elites amongst the rebels. Santana, on his own initiative, declared that annexation by Mexico was something that the rebels were considering on 17 August 1850.

Pedro Santana

Colombia was the first to support the Dominican rebels, covertly sending materials to the Dominican rebels through the port of Barahona. Their rationale was that Haiti was close to the United States’ sphere of influence, and Colombia wanted to limit the United States’ ambitions in the Caribbean out of fear that they would eventually make a move for Puerto Rico to turn it into a slave state. If Santo Domingo joined Mexico, it could work out better in the long run as Mexican interest in the Caribbean could increase and challenge America.

Mexico, upon hearing of the alleged Dominican interest in annexation, was thrown into a state of popular excitement. The Haitians attempted to force the Dominicans to grow cash crops, suppressed the use of Spanish and local customs (like cockfighting), seized the property of white Dominicans, and shut down the St. Thomas Aquinas University in Santo Domingo (more from a lack of teachers, students, and resources than outright despotism), so the popular Mexican image was of helpless Dominicans trying to fight against Haitian oppressors and join the egalitarian, modern, and amazing Mexican Empire.

The government was less sure, taking land from another Amphictyon would set a bad precedent and could potentially lead to infighting amongst the League. However, the League didn’t know which Haitian government could be considered the legitimate one. Legally, it was President Pierrot, but General Soulouque was promising legitimacy through democracy.

Between the end of August and the beginning of September, the League held an informal vote to see whether or not the League would intervene on behalf of President Pierrot against General Soulouque and the Dominicans. Two countries voted yes (the United States and Peru), four countries voted no (Colombia, Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile), and two countries abstained (Mexico and Paraguay). Without unanimous support any intervention was considered unlawful, but the United States joined Colombia in covertly attempting to supply their side.

Colombian President Vicente Ramón Roca sent a message to the Mexican government asking them to apply diplomatic pressure on the Dominicans behalf with the American government. Empress Zenaida was in favor of intervention, as were much of the Conservatives, but Prime Minister Álvarez was opposed (the Liberal opposition to the annexation of Santo Domingo probably contributed to their loss of the Assembly).

That didn’t stop Foreign Minister José Joaquín de Herrera and the Empress Zenaida from opening up negotiations with President Dallas and Secretary of State James Buchanan to secure a plan for Hispaniola.

The plan was simple: the United States could aid President Pierrot in exchange for him recognizing Santo Domingo’s independence. Santo Domingo would then hold a referendum to decide whether to remain independent or accept annexation by Mexico.

The Herrera-Buchanan Resolution passed unanimously with the League (with the exception of Paraguay, who abstained), and the Mexicans and Yankees sent expeditionary forces into Santo Domingo and Haiti. What the Yankees and Mexicans didn't tell the others, however, was that Haiti was to become an informal protectorate of the United States, much like Liberia in Africa.

The expeditionaries arrived in January 1851 and by April 1851, the situation in Santo Domingo was considered safe enough for plans to begin on the referendum on Dominican sovereignty. The elections would take place on November 1, 1851 to give the Dominicans enough time to make a decision.

What ended up happening was that native Dominicans started chasing French-speaking Afro-Caribbeans that Haiti received from the Frankish Islands and Cayenne into Haiti, and the Dominican elite, with the help of Mexican businesses that wanted in on the Dominican markets and industries, started organizing and distributing propaganda. They argued that an independent Santo Domingo would be severely impoverished and vulnerable to foreign influence and reconquest from Haiti. The Mexican Empire was portrayed as a light-handed and culturally identical overlord who could bring in money and expertise for rebuilding.

Out of a population of slightly less than 1.5 million, 553,127 voted in favor of “union” (pro-annexation forces managed to replace the word “annexation” with “union” on the ballot) and 145,321 voted for independence (roughly 79.2% to 20.8%). The election would probably fail most standards for fair, balanced, and open elections (there was public balloting, reports of bought votes, ballot fraud, harassment of pro-independence voters by paramilitary unionists and the actual Mexican army, and illegal women voting), but most modern historians and scholars accept that the majority of Dominicans wanted union (usually estimates are in the mid-to-high fifties).

Still, it’s possible that tensions would have broken out, if not for the fact that the Mexican Assembly allowed Santo Domingo to be admitted as a state extremely quickly on account of its population, and Mexican capital started flowing in. Democratic elections for representation in local and national assemblies occured in 1854, and, in a highly symbolic gesture, Emperor Luciano taught a biology lesson in the newly reopened (and relatively cheap) St. Thomas Aquinas University on August 31, 1853.

The first democratically elected governor of Santo Domingo was not Santana, but instead the Liberal and (originally) pro-independence politician Juan Pablo Duarte. His big agenda item was reforming the election process in the state.

Juan Pablo Duarte; Governor of Santo Domingo, 1855-1864

¹In honor of Pope Martin V, whose election ended the Western Schism, an apt comparison to what was essentially a Catholic Civil War.

² Empress Zenaida’s husband was given the full title of Emperor but no actual power. “The Expendable Emperor” proved a decent diplomat and was famous in Mexico as a patron of the sciences and education

Domestic Policy

Mexican Catholic Church

Following the Reactionary Revolt and the mass purging of reactionary bishops (and the occasional innocently conservative bishop), including the Archbishop of Mexico City, the Catholic Church in Mexico was in a weird spot. The long conclave and ensuing war between Catholic powers that saw Pope Julius IV flee Rome also prevented much in the way of resolution, so Emperor José, acting in the interest of the Church and in his position of defender of the Catholic faith in Mexico, started appointing bishops and priests from the laity (even a few dozen nuns) and priory schools who agreed with a roughly Christian humanist outlook or were just docile in political matters.

The goal was ultimately to keep the basic church infrastructure running, but the blatant caesaropapism made pro-Church intellectuals and politicians really nervous. If it weren’t for the circumstances leading to a loss of legitimacy for the Church and the Mexican populace wanting a quick return to normalcy after the Revolt, the powergrab probably would have lead to riots. Plus the Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs had the sense to make sure that as many as the replacements as possible had some existing connection to or approval from the community, so it was an easier pill to swallow.

The government’s appointment of bishops during this period almost masked the fact that the government was widely confiscating Church lands and arresting pro-Church newspapermen and publishers. The land was either sold to the people working the land if they supported the government or transferred to the state government as a reward for loyalty. This may have contributed to the Panic of 1847 in Mexico as farmers couldn’t pay back loans on land and equipment and there was a general fear for property rights. Most of the publishers were eventually released by the Senate Board of Freedom of the Press, but their equipment and offices had long since been seized, stolen, or lost, and the government refused to recompense them.

The message was clear: “Stay in line or be crushed.”

Still, events might have played out differently if it weren’t for the election of pro-Bonapartist Cardinal Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti as Pope Martin VI¹ in 1846. Pope Martin legitimized the appointments made by Emperor José and negotiations were begun during the first year of Empress Zenaida’s reign to see if the Catholic Church in Mexico could be given sui iuris full communion with the Papacy like the Eastern Catholic Church.

These negotiations, largely personally between Pope Martin VI and Emperor Luciano I² bore fruit in 1849 with the Glorious Reform (or Glorious Concordat). The Archbishop of Mexico City was given full authority over nominations and promotions within the Mexican Catholic Church, but the Archbishop had to be nominated by the pope and approved by the Emperor/Empress. Likewise, the Mexican Church was given the authority to bless Mexican individuals in a unique beatification ceremony as it saw fit and maintain its own traditions.

To celebrate, Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, the famed Native Mexican who saw apparitions of the Virgin Mary at Tepeyac Hill and received the famous tilma with her appearance, was beatified on Christmas Day 1849, and the first mass entirely in the vernacular was held at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe on New Year’s Day 1850, with the royal family in attendance.

These innovations actually worked in bringing back popular confidence in the Church as an instrument of public good and a worthwhile Mexican institution, and the new preachers found willing flocks to hear state-friendly sermons. Still, the Church remained influential, if different. For example, most of the radical interventionalists who pushed for war with the United States to free the slaves were preachers and their flocks.

In 1853, the Archbishop of Mexico City declared that the Mexican Catholic Church would recognize marriage between slaves. This, and Pope Martin VI’s declaration that owning Christians was a grave sin, resulted in the burning of several Catholic Churches in the Southern United States, restrictions on black participation in Catholic mass, conversions of several slaveholders to some form of Protestantism, and Cubans selling their plantations and slaves to absentee owners (absentee plantations in the Yankee Caribbean were worse than average; the overseers didn’t care if the owner had to spend money on a new slave). While the Archbishop’s naive plan to make the lives of slaves easier (“Surely, they wouldn’t separate lawfully recognized families, would they? Plus it would make the slaves so happy.”) backfired, Mexicans were outraged at the treatment of the Church by pro-slavery forces.

The Birth of Labor & the Death of Debt Peonage

Juan Álvarez; Prime Minister of Mexico, 1848-1855

Before the outbreak of the California Gold Rush, the Mexican Empire was on a bimetallic (gold and silver) currency, but the mass influx of gold rose the relative price of silver and increased the money supply, meaning that inflation and a monetary supply shock were concerns. In order to stabilize the economy, Liberal leadership under Prime Minister Álvarez and Conservative leadership under Deputy José Ignacio Pavón settled on an agreement to switch the country to a pure gold standard.

Two factions within the Liberal Party, the Reformers and Worker’s Men, however, opposed the plan and managed to halt the process. They wanted to improve the lives of poor farm workers, disproportionately Native Americans, who were caught in the system of debt peonage; their argument was that inflation was a good thing as it made the debts that the poor owed to their landlords worth less and easier to pay off. These men were under the leadership of a Zapotec man from the state of Oaxaca called Benito Juárez.

Talks between the “elitists” and “anarchists” collapsed, and the threat of another panic loomed at the capital. Empress Zenaida, in the imperial role of mediator, called on the party leadership and factional leaderships for the workers, industrialists, and landowners to meet with her and her full ministry to settle the dispute. If they refused, she would dissolve the Chamber of Deputies and hold new elections when it was clear someone would win a majority.

The result was the Compromise of 1853. The country was set to transition to the gold standard, but the plight of the debt peons would be addressed in what became known as the “Peon Bill of Rights” (“Carta de Derechos del Peón”). The main points are as follows:

- The peon must either be paid in money or goods that can be directly sold for money at any reasonable marketplace. This was meant to limit the practice of giving peons notes that could only be redeemed at an hacienda’s store, where the peons would usually find prices intended to keep them in debt.

- Indebted workers can only be prevented from leaving the hacienda with a warrant issued by a federal judge if there’s significant reason to believe the debtor will not pay their debt, said warrant can never last more than a year but could be renewed indefinitely.

- Peons have the right to collectively bargain and to seek legal representation when writing their contracts. However, the legal representation would be at the peons’ expense and the collectives could only negotiate with one landowner at any given time and had to be locally based.

- Peons can sell their product to any merchant to pay their lease or buy equipment from any merchant, unless their contract stipulates a set amount of money for the labor and that all product goes to the landowner.

The final vote was 115-105 in favor, with certain industrialists and merchants being the surprise allies to labor in this instance. Industrialists figured that free peons moving to the urban centers and factories would lower wages in general, and the merchants hoped that direct access to the peons would mean better prices. (They knew, for instance, that a landowner could buy equipment for say 350 pesos and then sell it to the laborers for 450. Now, the merchants could sell it directly to the peons for 400, thus making a larger profit and being a good guy to the new customer.) Both also liked the chance to challenge the power and influence of the large landowners and secure a stable currency. Naturally, they refused to accept that the act applied to industrial workers and did everything in their power to prevent it, successfully.

This move solidified Mexico’s growing reputation as “the Liberal Empire” and led to the first recorded instance of Empress Zenaida’s popular nickname “La Gran Dama” (“The Great Lady”) among the working classes who increasingly saw her as their champion. For Juárez, it met a brief stint as Minister of Indian Affairs (1854-1855) and national press that could hopefully help his push to the premiership.

The elections the following year did, however, show a slight move away from radical reform as moderates and Conservatives took the premiership under Rómulo Díaz de la Vega.

Rómulo Díaz de la Vega; Prime Minister of Mexico, 1855-1859

Foreign Policy

The Treaty of Kingston (1846)

In her coronation speech, Empress Zenaida claimed that she wasn’t a puppet of Rome, and Britain was willing to test her by attempting to negotiate a firm border for British Honduras. Foreign Ministers José Joaquín de Herrera and the Viscount Palmerston negotiated by proxy in Kingston, Jamaica, and the Treaty of Treaty was ratified by the British Parliament and Mexican Assembly on 23 April 1846.

Mosquito Bay was recognized as Mexican territory, British Honduras was recognized as British territory to be renamed “Belize” to distinguish it clearly from the Mexican territory of Honduras, Belize would be given full free-trade access to Mexican markets and vice versa, Belize would be given a local, democratically-elected parliament with limited powers over domestic, Mayan, affairs, and a railroad would be constructed between Belize City and Guatemala City.

Dominican Revolution of 1850

On 9 July 1850, President Jean-Pierre Boyer of Haiti died, triggering a succession crisis. General Faustin Soulouque called for new elections, but Vice-President Jean-Louis Pierrot (the de jure president) claimed that there was no need. General Soulouque led his troops into open rebellion calling for new elections and a greater democratization of the country.

In the eastern, former Spanish part of the island, the Dominicans, under the leadership of Pedro Santana y Familias and Juan Pablo Duarte. Santana, however, figured that Santo Domingo, with a smaller population and questionable economical prospects, would constantly struggle and would be better off annexed by a larger power. He tried to sell his fellow revolutionaries on the idea that the Dominicans should seek annexation by Mexico, a plan generally supported by conservatives and elites amongst the rebels. Santana, on his own initiative, declared that annexation by Mexico was something that the rebels were considering on 17 August 1850.

Pedro Santana

Colombia was the first to support the Dominican rebels, covertly sending materials to the Dominican rebels through the port of Barahona. Their rationale was that Haiti was close to the United States’ sphere of influence, and Colombia wanted to limit the United States’ ambitions in the Caribbean out of fear that they would eventually make a move for Puerto Rico to turn it into a slave state. If Santo Domingo joined Mexico, it could work out better in the long run as Mexican interest in the Caribbean could increase and challenge America.

Mexico, upon hearing of the alleged Dominican interest in annexation, was thrown into a state of popular excitement. The Haitians attempted to force the Dominicans to grow cash crops, suppressed the use of Spanish and local customs (like cockfighting), seized the property of white Dominicans, and shut down the St. Thomas Aquinas University in Santo Domingo (more from a lack of teachers, students, and resources than outright despotism), so the popular Mexican image was of helpless Dominicans trying to fight against Haitian oppressors and join the egalitarian, modern, and amazing Mexican Empire.

The government was less sure, taking land from another Amphictyon would set a bad precedent and could potentially lead to infighting amongst the League. However, the League didn’t know which Haitian government could be considered the legitimate one. Legally, it was President Pierrot, but General Soulouque was promising legitimacy through democracy.

Between the end of August and the beginning of September, the League held an informal vote to see whether or not the League would intervene on behalf of President Pierrot against General Soulouque and the Dominicans. Two countries voted yes (the United States and Peru), four countries voted no (Colombia, Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile), and two countries abstained (Mexico and Paraguay). Without unanimous support any intervention was considered unlawful, but the United States joined Colombia in covertly attempting to supply their side.

Colombian President Vicente Ramón Roca sent a message to the Mexican government asking them to apply diplomatic pressure on the Dominicans behalf with the American government. Empress Zenaida was in favor of intervention, as were much of the Conservatives, but Prime Minister Álvarez was opposed (the Liberal opposition to the annexation of Santo Domingo probably contributed to their loss of the Assembly).

That didn’t stop Foreign Minister José Joaquín de Herrera and the Empress Zenaida from opening up negotiations with President Dallas and Secretary of State James Buchanan to secure a plan for Hispaniola.

The plan was simple: the United States could aid President Pierrot in exchange for him recognizing Santo Domingo’s independence. Santo Domingo would then hold a referendum to decide whether to remain independent or accept annexation by Mexico.

The Herrera-Buchanan Resolution passed unanimously with the League (with the exception of Paraguay, who abstained), and the Mexicans and Yankees sent expeditionary forces into Santo Domingo and Haiti. What the Yankees and Mexicans didn't tell the others, however, was that Haiti was to become an informal protectorate of the United States, much like Liberia in Africa.

The expeditionaries arrived in January 1851 and by April 1851, the situation in Santo Domingo was considered safe enough for plans to begin on the referendum on Dominican sovereignty. The elections would take place on November 1, 1851 to give the Dominicans enough time to make a decision.

What ended up happening was that native Dominicans started chasing French-speaking Afro-Caribbeans that Haiti received from the Frankish Islands and Cayenne into Haiti, and the Dominican elite, with the help of Mexican businesses that wanted in on the Dominican markets and industries, started organizing and distributing propaganda. They argued that an independent Santo Domingo would be severely impoverished and vulnerable to foreign influence and reconquest from Haiti. The Mexican Empire was portrayed as a light-handed and culturally identical overlord who could bring in money and expertise for rebuilding.

Out of a population of slightly less than 1.5 million, 553,127 voted in favor of “union” (pro-annexation forces managed to replace the word “annexation” with “union” on the ballot) and 145,321 voted for independence (roughly 79.2% to 20.8%). The election would probably fail most standards for fair, balanced, and open elections (there was public balloting, reports of bought votes, ballot fraud, harassment of pro-independence voters by paramilitary unionists and the actual Mexican army, and illegal women voting), but most modern historians and scholars accept that the majority of Dominicans wanted union (usually estimates are in the mid-to-high fifties).

Still, it’s possible that tensions would have broken out, if not for the fact that the Mexican Assembly allowed Santo Domingo to be admitted as a state extremely quickly on account of its population, and Mexican capital started flowing in. Democratic elections for representation in local and national assemblies occured in 1854, and, in a highly symbolic gesture, Emperor Luciano taught a biology lesson in the newly reopened (and relatively cheap) St. Thomas Aquinas University on August 31, 1853.

The first democratically elected governor of Santo Domingo was not Santana, but instead the Liberal and (originally) pro-independence politician Juan Pablo Duarte. His big agenda item was reforming the election process in the state.

Juan Pablo Duarte; Governor of Santo Domingo, 1855-1864

¹In honor of Pope Martin V, whose election ended the Western Schism, an apt comparison to what was essentially a Catholic Civil War.

² Empress Zenaida’s husband was given the full title of Emperor but no actual power. “The Expendable Emperor” proved a decent diplomat and was famous in Mexico as a patron of the sciences and education

Well, looks like the slavery tensions are getting worse.

It’s looking likely that when a US Civil War breaks out, Mexico will support the Union and abolitionists.

Beyond that, things are looking up nicely.

I wonder what literature will be made st the turn of the century. The Americans tended to have mundane or magical realist stuff compared to the rising fantasy and sci-fi Europe had. I could see the fantasy and science fiction take root in Mexico as part of a greater fascination for their native past

It’s looking likely that when a US Civil War breaks out, Mexico will support the Union and abolitionists.

Beyond that, things are looking up nicely.

I wonder what literature will be made st the turn of the century. The Americans tended to have mundane or magical realist stuff compared to the rising fantasy and sci-fi Europe had. I could see the fantasy and science fiction take root in Mexico as part of a greater fascination for their native past

Last edited:

Well, looks like the slavery tensions are getting worse.

It’s looking likely that when a US Civilian award breaks out, Mexico will support the Union and abolitionists.

Beyond that, things are looking up nicely.

I wonder what literature will be made st the turn of the century. The Americans tended to have mundane or magical realist stuff compared to the rising fantasy and sci-fi Europe had. I could see the fantasy and science fiction take root in Mexico as part of a greater fascination for their native past

Not just a Civil War, ITTL Reconstruction will probably have support from Mexico (if for no other reason than to not be the Promised Land for millions of newly freed slaves) and the Catholic Church (amongst others). We could see a significant number of Afro-Americans in the Deep. South convert to Catholicism, which would have an interesting effect on the Church and them (maybe a more liberal Pope Francis-like figure earlier or an Afro-American archbishop or cardinal).

Plus a longer, better-funded Reconstruction with different interests playing out could be a benefit for poor Southeners in general (let's not forget that simple things like public schools were a Reconstruction project).

As for literature, the native past and the weakening of the Church could lead to fantasy becoming a big genre. I can see books written about brave Mestizo adventurer/scientists trying to find ancient Aztec codecs before white supremacist "Southern Yankees" can destroy them or claim credit for their knowledge.

Not just a Civil War, ITTL Reconstruction will probably have support from Mexico (if for no other reason than to not be the Promised Land for millions of newly freed slaves) and the Catholic Church (amongst others). We could see a significant number of Afro-Americans in the Deep. South convert to Catholicism, which would have an interesting effect on the Church and them (maybe a more liberal Pope Francis-like figure earlier or an Afro-American archbishop or cardinal).

Plus a longer, better-funded Reconstruction with different interests playing out could be a benefit for poor Southeners in general (let's not forget that simple things like public schools were a Reconstruction project).

As for literature, the native past and the weakening of the Church could lead to fantasy becoming a big genre. I can see books written about brave Mestizo adventurer/scientists trying to find ancient Aztec codecs before white supremacist "Southern Yankees" can destroy them or claim credit for their knowledge.

Yeah, Mexico I reckon will be a thorough so that something like the KKK would not rise or so on. I do think a good few of the free slaves would settle in the north and so on.

I do think that Mexico will try and frame the thing of the slaves and so on as the slaves, poor farmers and yeomen against the quasi-aristocratic planters. It would benefit them in the long run to have that be the mentality rather than the “noble South” thing.

The rise of European-styled fantasy literature in Mexico will make a fascinating contrast to the US, who may hop on the sci-fi bandwagon as we saw bits and pieces of IOTL. And then of course, each would influence the other, especially as US fantasy authors and Mexico sci-fi writers rise up.

Like, I’m imagining a Mexican version of the Vril novel

Yeah, Mexico I reckon will be a thorough so that something like the KKK would not rise or so on. I do think a good few of the free slaves would settle in the north and so on.

I do think that Mexico will try and frame the thing of the slaves and so on as the slaves, poor farmers and yeomen against the quasi-aristocratic planters. It would benefit them in the long run to have that be the mentality rather than the “noble South” thing.

The rise of European-styled fantasy literature in Mexico will make a fascinating contrast to the US, who may hop on the sci-fi bandwagon as we saw bits and pieces of IOTL. And then of course, each would influence the other, especially as US fantasy authors and Mexico sci-fi writers rise up.

Like, I’m imagining a Mexican version of the Vril novel

If the Union doesn't implement Mexico's policy of arming resistors to rebels and then killing as many rebels leaders as they can get their hands on, then Mexico will. Good cop, bad cop invasions of the South.

I'm going to do a few more posts on Mexico (including misadventures in the Far East) and United States before returning to the European Cold War, could throw some cultural developments as a bridge between the two.

If the Union doesn't implement Mexico's policy of arming resistors to rebels and then killing as many rebels leaders as they can get their hands on, then Mexico will. Good cop, bad cop invasions of the South.

I'm going to do a few more posts on Mexico (including misadventures in the Far East) and United States before returning to the European Cold War, could throw some cultural developments as a bridge between the two.

Yeah, that definitely makes sense and the Union won't exactly refuse the help. Heck, it might draw them closer together as the US seeing Mexico helping them in their time of need.

Far East sounds interesting though I don't see Mexico having any colonial ambitions out in the Pacific (maybe they end up with the Philippines by accident or they strike a friendship with Korea or the Thai Rattanakosin Kingdom.)

The culutral developments are among the most enjoyable because it makes the world feel more vibrant and real. Especially since we're getting to the point where art, literature, music and so on become more defining features of a nation. Heck, many of the classical European works of fantasy and sci-fi would come to be written in the upcoming decades, something that would no doubt capture the imaginations of future writers and something that the US's public domain is sadly lacking in (though the inanity of the copyright laws don't help as well.)

Hence, seeing some of these changes adds more to the richness of it.

Chapter XXIX: Mexican Misadventures in the Far East

Mexican Misadventures in the Far East

Great Britain and, to a lesser extent, the Netherlands and Portugal dominated trade with China and the Far East from their positions in India, the Philippines, and the East Indies. Mexico, with its strong relations with Hawaii and ports on the Pacific, wanted a share of the Asian market and the advantage of being the first American power in the region.

An expedition entering planning a month after the ascension of Prime Minister de la Vega in 1855, under the influence of the ambitious new Foreign Minister José María Gutiérrez de Estrada, War Minister Juan Nepomuceno Almonte Ramírez, Treasury Minister Manuel Doblado Partida, and the young Prince José.

The expedition was not immediately popular in the Chamber of Deputies. Liberals under the emerging leadership of Benito Juarez denounced imperialism (when someone brought up Mexican Africa they countered that at least Mexico had a claim to the territory) and several Conservative deputies expressed reservations about the costs and risks of a venture.

Still, the public was interested in Mexico's place in the wider world following the annexation of Santo Domingo and business interests were in favor of expanding Mexican commerce, so a resolution approving the preparation of ships and gathering of resources outside of the normal naval budget was approved.

The expedition was outfitted under the leadership of Admiral Agustin José de Iturbide y Bonaparte, grandson of Emperor José I and Duque Agustin de Iturbide. with the goal of making contact with the various kingdoms and peoples in the Pacific. As grandson of the previous emperor and nephew of Empress Zenaida, it was hoped that he would be an acceptable royal emissary. The five vessels: Emperador Luciano, Jalisco, California, Costa Rica, and Princesa Carlota left Acapulco on 12 April 1856, amidst much fanfare.

Japan

Japan was the first stop for the expedition, entering the port of Nagasaki on 21 October 1856 with special permission from chief rōjū Hotta Masayoshi and Tokugawa shogun Tokugawa Iesada.

Following three massive earthquakes from 1854-5 and the outbreak of the Second Opium War, featuring a joint British and Dutch invasion of China, the shogunate was willing to listen to what Mexican diplomats had to offer.

Admiral de Iturbide and later historians argued that it was the Dutch involvement in the Second Opium War that played the biggest factor in starting negotiations. Seeing the only Western country allowed into Japan as a colonial aggressor led to a belief among some of the leading officials that at least a few more Western partners could help maintain Japanese sovereignty in the long term.

The “Japan-Mexico Treaty of Peace and Amity,” written in Spanish, Dutch, Chinese, and Japanese had the following main points: Mexican ships could buy coal from Japanese merchants; the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate would be opened to Mexican trade; and a Mexican consul would be established in Shimoda. Later treaties would facilitate the exchange of diplomatic agents and the right of Mexicans to reside in Japan and lease property, as long as they accepted that they would be under the Japanese legal system and courts while they stayed in Japan and that they could only practice their religion in special foreign communities.

The shogunate sold the treaty to its people as a sign of sovereignty, that they entered the talks as equals and came away with an agreement that would allow for trade with Western powers as equal partners.

To their credit, the Mexican Expeditionary Force acted with restraint and in “the full spirit of peaceful diplomacy.”

Korea

The expedition landed in Busan in Southern Korea in April 1857.

The Kingdom of Joseon was not in a good state. Royal in-laws, the Andong Kims, had effectively seized power and were in control of the succession to the throne and monopolized the vital positions in government. Corruption and disorder were rampant: Government offices and posts were products to be sold, the Korean population was severely impoverished, and there were constant uprisings.

The King of Joseon, Cheoljong, was born into poverty in Ganghwa after his family fled oppression and persecution at the hand of the roya in-laws. He was illiterate and knew nothing of courtly ceremony, making him a perfect puppet.

While the expedition was amicably received by the local officials, the poverty of the region and mess in the court turned them off from any serious attempts to open trade with Joseon. After all, with Japan already befriended, with its precious coal for refueling and ports open, there was no need to deal with an unstable country. They stayed in Joseon for less than a month.

Brunei

The Sultanate of Brunei was the next great success of the expedition. After a brief stay in Japan and the British-held Philippines, the expedition landed in Brunei Town and was warmly greeted by Sultan Abdul Momin in July 1857.

The Sultan had a problem: the British. The previous sultan, his father-in-law, had given the British adventurer James Brooke complete sovereignty over an independent kingdom in Sarawak as Rajah of Sarawak in exchange for Brooks’ aid in putting down rebellions and hunting pirates back in 1841. In 1855, three years into Abdul Momin’s reign, he had forced the Sultan to grant him more territory.

Shortly after the arrival of the Mexican Expedition, a British envoy arrived on 26 November 1857 to reconfirm the conditions of an earlier Treaty of Friendship and Commerce in 1847. Although Brunei was no longer as important to Great Britain following the acquisition of the Philippines, the thought of another Western power trying to gain a foothold in the region was concerning, especially considering the Mexicans’ success in Japan and historical ties to the Philippines.

The Sultan said that he wanted the Mexican envoys to act as mediators and that he would no longer accept any conditions that he felt encroached on Brunei’s ability to deal with foreign powers besides Great Britain.

What followed was a year long, diplomatic Mexican standoff between Great Britain, Mexico, and Brunei that tested Mexican commitment to its Asian policy. No one pretended that the Mexican Navy was a match for the British, but the British had the Opium War in China, the Sepoy Mutiny in India, and Bonapartist posturing in Europe as more pressing concerns. Moreover, there was still concern in London that the American nations would join forces with the Bonapartists in the event of war and that going to war with Mexico over trading rights to a small kingdom would probably sour opinion in the Western Hemisphere.

The Second Treaty of Friendship and Commerce between Britain and Brunei maintained the special privileges for British citizens in Brunei, reaffirmed Brooks’ rights to his kingdom, established free trade between Britain and Brunei, but Brunei established its right to lease lands out to foreigners (under the first treaty Britain attempted to prevent Brunei from giving any territory to rival powers) and to defend its territories from any incursions from Brooks or other powers by any means necessary. It was ratified by both parties in February 1859

The Treaty of Cooperation between Mexico and Brunei established the mutual exchange of diplomatic agents, the right of Mexican businessmen to operate in Brunei, and a program that would allow Bruneian military officers to study in Mexican military academies. It was ratified by both parties in October 1859.

By 1890, the first generation of Mexican-trained Bruneian officers and roughly 150 Mexican military advisors were reforming the army in Brunei, and a continued Mexican presence in Bruneian waters was established by 1865 to deter Brooks from attacking.

Indochina

Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, King Luís I of Portugal due to his marriage to Queen Maria II of Portugal, had imperialist ambitions. Besides the general arguments of economic opportunity and national glory, he viewed the expansion and strengthening of the Portugese Empire as accomplishing two main foreign policy objectives: rivaling the influence of the British and positioning his branch of the Bonaparte dynasty as major players within the Bonapartist alliance. Even though his children were, according to the Portuguese Constitution, members of the House of Braganza, Luís imagined himself as the patriarch of a new House of Braganza-Bonaparte, and he wanted his branch of the family to rival the Roman and Mexican branches of the family. The most available means of achieving that end, he decided was expanding Portuguese territory abroad and acquiring new territory abroad.

Portugal had been slowly expanding its influence in Vietnam over the course of the 1840s and 1850s, joining the missionary efforts of the France after the collapse of the Kingdom of Spain. Vietnam provided him with the perfect casus belli for intervention when the Vietnames emperor Tự Đức approved the execution of a Portuguese Catholic missionaries in 1857. This wasn’t the first time that a Catholic missionary was executed by the government, and in the past the Europeans had done nothing major. This time, however, Luís had the domestic support and foreign approval to launch an expedition to Vietnam.

Knowing of the Mexican Empire’s interest in the region, he approached the Mexican government about a joint expedition. Prince José and newly ascended Prime Minister Manuel Robles Pezuela were in favor of the intervention, and they managed to convince the Empress and the Congress to approve a limited intervention. They still had some ships and men out in Brunei as part of the original expedition, and the operation was to protect Catholics after all. Robles and the other interventionists sold it as a quick, painless, and completely justified conflict.

What followed was a three-year campaign that wasn’t as easy as Prime Minister Robles had promised. Mexico had to send more men and ships to help the Portuguese after the initial expeditionary force was besieged in Đà Nẵng and failed to make any major gains. Events unfolding in Europe in 1860 threatened the entire venture as it was thought that Portugal would have to pull out, and when the Mexicans tried to exit the war with moderate terms (no territorial changes but guaranteed protection of Vietnamese Catholics), the Vietnamese emperor, thinking he had the upper hand, refused. He was probably hoping that the Mexicans and Portuguese would have to leave without securing any concessions from the Vietnamese.

Hoping to salvage the situation, Prime Minister Robles committed more troops and resources to shift the momentum in their favor over the course of 1861 and 1862. The surge was enough to break the stalemate and take more territory, but the emperor tried his hand at guerilla warfare. What followed was a brutal occupation of taken territories that reflected poorly on the Mexican forces and stirred popular discontent at home. Still, the emperor knew his situation was untenable in the long term: The invading forces were succeeding in taking major cities and preventing the flow of resources to the Vietnamese forces.

Negotiations for a final peace finally began in March 1862. The Mexican delegation was bitterly divided internally, some were hardcore imperalists and others just wanted an honorable exit for Mexico. About the only thing they could agree on was that, almost to a man, they were really pissed at the Portuguese, who wanted territory despite (in the eyes of the Mexicans) not contributing their fair share.

In the terms of the following Treaty of Saigon of June 1862, the Portuguese got what they really wanted: some territory in the form of the provinces of Vĩnh Long, An Giang, and Hà Tiên. The Mexicans got a guarantee of the right of Catholics to practice their religion freely and the cessation of Hanoi and some territory along the Hong River. Prime Minister Robles hoped that this would be enough to save his premiership, but when the terms of the treaty were announced, the Liberals demanded his head. Most demanded to know, “Why did Mexicans die for Protuguese gains?” Some hardline anti-imperialist even asked, “Why did we participate in the theft of Vietnamese lands? Weren’t we only there to defend the Church?” His own party was unwilling to defend him, and the Prince of the Union was forced by the Empress to withdraw his support of Prime Minister Robles and sent to Costa Rica to keep him away from Mexico City.

The attacks contributed to the fall of the Conservative control of the Chamber of Deputies following the 1861 elections. Robles retired from politics after it became clear the Conservatives (many of them the same deputies who encouraged the war at first) didn’t want him to be the face of the party in the new Chamber. He would forever defend his actions in regards to the First Mexican Intervention in Vietnam.

Even though the acquisition of Hanoi was lambasted at the times, none of his successors to the post wanted to take the potential risk of returning it to the Vietnamese and being accused of losing Mexican territory paid for in Mexican blood. Part of that calculus also came from later analysis that found that the anti-imperialists, although vocal, weren’t the clear majority of the Mexican electorate. Most of the damage done to Robles and this intervention in particular stemmed from an unpopular peace: the terms were largely unpopular because it was felt like the Portuguese got more for doing less. It’s been argued that Robles could have held on to power if he either committed to not taking territory or took more and that, overall, he was the fall guy for a larger imperialist cabal that played their hand poorly.

For her part, the Empress was reportedly appalled at the lengths the Mexican Army went to to suppress the guerillas, but she still signed the treaty. In private correspondence, she stated that she felt it was a fait accompli, that to veto the treaty would weaken the position of Mexican diplomats and reflect poorly on herself and her son. It’s not entirely without merit that some quote the words used to describe Empress Maria Theresa’s involvement with the First Partition of Poland: “The more she cried, the more she took.”

Great Britain and, to a lesser extent, the Netherlands and Portugal dominated trade with China and the Far East from their positions in India, the Philippines, and the East Indies. Mexico, with its strong relations with Hawaii and ports on the Pacific, wanted a share of the Asian market and the advantage of being the first American power in the region.

An expedition entering planning a month after the ascension of Prime Minister de la Vega in 1855, under the influence of the ambitious new Foreign Minister José María Gutiérrez de Estrada, War Minister Juan Nepomuceno Almonte Ramírez, Treasury Minister Manuel Doblado Partida, and the young Prince José.

The expedition was not immediately popular in the Chamber of Deputies. Liberals under the emerging leadership of Benito Juarez denounced imperialism (when someone brought up Mexican Africa they countered that at least Mexico had a claim to the territory) and several Conservative deputies expressed reservations about the costs and risks of a venture.

Still, the public was interested in Mexico's place in the wider world following the annexation of Santo Domingo and business interests were in favor of expanding Mexican commerce, so a resolution approving the preparation of ships and gathering of resources outside of the normal naval budget was approved.

The expedition was outfitted under the leadership of Admiral Agustin José de Iturbide y Bonaparte, grandson of Emperor José I and Duque Agustin de Iturbide. with the goal of making contact with the various kingdoms and peoples in the Pacific. As grandson of the previous emperor and nephew of Empress Zenaida, it was hoped that he would be an acceptable royal emissary. The five vessels: Emperador Luciano, Jalisco, California, Costa Rica, and Princesa Carlota left Acapulco on 12 April 1856, amidst much fanfare.

Japan

Japan was the first stop for the expedition, entering the port of Nagasaki on 21 October 1856 with special permission from chief rōjū Hotta Masayoshi and Tokugawa shogun Tokugawa Iesada.

Following three massive earthquakes from 1854-5 and the outbreak of the Second Opium War, featuring a joint British and Dutch invasion of China, the shogunate was willing to listen to what Mexican diplomats had to offer.

Admiral de Iturbide and later historians argued that it was the Dutch involvement in the Second Opium War that played the biggest factor in starting negotiations. Seeing the only Western country allowed into Japan as a colonial aggressor led to a belief among some of the leading officials that at least a few more Western partners could help maintain Japanese sovereignty in the long term.

The “Japan-Mexico Treaty of Peace and Amity,” written in Spanish, Dutch, Chinese, and Japanese had the following main points: Mexican ships could buy coal from Japanese merchants; the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate would be opened to Mexican trade; and a Mexican consul would be established in Shimoda. Later treaties would facilitate the exchange of diplomatic agents and the right of Mexicans to reside in Japan and lease property, as long as they accepted that they would be under the Japanese legal system and courts while they stayed in Japan and that they could only practice their religion in special foreign communities.

The shogunate sold the treaty to its people as a sign of sovereignty, that they entered the talks as equals and came away with an agreement that would allow for trade with Western powers as equal partners.

To their credit, the Mexican Expeditionary Force acted with restraint and in “the full spirit of peaceful diplomacy.”

Korea

The expedition landed in Busan in Southern Korea in April 1857.

The Kingdom of Joseon was not in a good state. Royal in-laws, the Andong Kims, had effectively seized power and were in control of the succession to the throne and monopolized the vital positions in government. Corruption and disorder were rampant: Government offices and posts were products to be sold, the Korean population was severely impoverished, and there were constant uprisings.

The King of Joseon, Cheoljong, was born into poverty in Ganghwa after his family fled oppression and persecution at the hand of the roya in-laws. He was illiterate and knew nothing of courtly ceremony, making him a perfect puppet.

While the expedition was amicably received by the local officials, the poverty of the region and mess in the court turned them off from any serious attempts to open trade with Joseon. After all, with Japan already befriended, with its precious coal for refueling and ports open, there was no need to deal with an unstable country. They stayed in Joseon for less than a month.

Brunei

The Sultanate of Brunei was the next great success of the expedition. After a brief stay in Japan and the British-held Philippines, the expedition landed in Brunei Town and was warmly greeted by Sultan Abdul Momin in July 1857.

The Sultan had a problem: the British. The previous sultan, his father-in-law, had given the British adventurer James Brooke complete sovereignty over an independent kingdom in Sarawak as Rajah of Sarawak in exchange for Brooks’ aid in putting down rebellions and hunting pirates back in 1841. In 1855, three years into Abdul Momin’s reign, he had forced the Sultan to grant him more territory.

Shortly after the arrival of the Mexican Expedition, a British envoy arrived on 26 November 1857 to reconfirm the conditions of an earlier Treaty of Friendship and Commerce in 1847. Although Brunei was no longer as important to Great Britain following the acquisition of the Philippines, the thought of another Western power trying to gain a foothold in the region was concerning, especially considering the Mexicans’ success in Japan and historical ties to the Philippines.

The Sultan said that he wanted the Mexican envoys to act as mediators and that he would no longer accept any conditions that he felt encroached on Brunei’s ability to deal with foreign powers besides Great Britain.

What followed was a year long, diplomatic Mexican standoff between Great Britain, Mexico, and Brunei that tested Mexican commitment to its Asian policy. No one pretended that the Mexican Navy was a match for the British, but the British had the Opium War in China, the Sepoy Mutiny in India, and Bonapartist posturing in Europe as more pressing concerns. Moreover, there was still concern in London that the American nations would join forces with the Bonapartists in the event of war and that going to war with Mexico over trading rights to a small kingdom would probably sour opinion in the Western Hemisphere.

The Second Treaty of Friendship and Commerce between Britain and Brunei maintained the special privileges for British citizens in Brunei, reaffirmed Brooks’ rights to his kingdom, established free trade between Britain and Brunei, but Brunei established its right to lease lands out to foreigners (under the first treaty Britain attempted to prevent Brunei from giving any territory to rival powers) and to defend its territories from any incursions from Brooks or other powers by any means necessary. It was ratified by both parties in February 1859

The Treaty of Cooperation between Mexico and Brunei established the mutual exchange of diplomatic agents, the right of Mexican businessmen to operate in Brunei, and a program that would allow Bruneian military officers to study in Mexican military academies. It was ratified by both parties in October 1859.

By 1890, the first generation of Mexican-trained Bruneian officers and roughly 150 Mexican military advisors were reforming the army in Brunei, and a continued Mexican presence in Bruneian waters was established by 1865 to deter Brooks from attacking.

Indochina

Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, King Luís I of Portugal due to his marriage to Queen Maria II of Portugal, had imperialist ambitions. Besides the general arguments of economic opportunity and national glory, he viewed the expansion and strengthening of the Portugese Empire as accomplishing two main foreign policy objectives: rivaling the influence of the British and positioning his branch of the Bonaparte dynasty as major players within the Bonapartist alliance. Even though his children were, according to the Portuguese Constitution, members of the House of Braganza, Luís imagined himself as the patriarch of a new House of Braganza-Bonaparte, and he wanted his branch of the family to rival the Roman and Mexican branches of the family. The most available means of achieving that end, he decided was expanding Portuguese territory abroad and acquiring new territory abroad.

Portugal had been slowly expanding its influence in Vietnam over the course of the 1840s and 1850s, joining the missionary efforts of the France after the collapse of the Kingdom of Spain. Vietnam provided him with the perfect casus belli for intervention when the Vietnames emperor Tự Đức approved the execution of a Portuguese Catholic missionaries in 1857. This wasn’t the first time that a Catholic missionary was executed by the government, and in the past the Europeans had done nothing major. This time, however, Luís had the domestic support and foreign approval to launch an expedition to Vietnam.

Knowing of the Mexican Empire’s interest in the region, he approached the Mexican government about a joint expedition. Prince José and newly ascended Prime Minister Manuel Robles Pezuela were in favor of the intervention, and they managed to convince the Empress and the Congress to approve a limited intervention. They still had some ships and men out in Brunei as part of the original expedition, and the operation was to protect Catholics after all. Robles and the other interventionists sold it as a quick, painless, and completely justified conflict.

What followed was a three-year campaign that wasn’t as easy as Prime Minister Robles had promised. Mexico had to send more men and ships to help the Portuguese after the initial expeditionary force was besieged in Đà Nẵng and failed to make any major gains. Events unfolding in Europe in 1860 threatened the entire venture as it was thought that Portugal would have to pull out, and when the Mexicans tried to exit the war with moderate terms (no territorial changes but guaranteed protection of Vietnamese Catholics), the Vietnamese emperor, thinking he had the upper hand, refused. He was probably hoping that the Mexicans and Portuguese would have to leave without securing any concessions from the Vietnamese.

Hoping to salvage the situation, Prime Minister Robles committed more troops and resources to shift the momentum in their favor over the course of 1861 and 1862. The surge was enough to break the stalemate and take more territory, but the emperor tried his hand at guerilla warfare. What followed was a brutal occupation of taken territories that reflected poorly on the Mexican forces and stirred popular discontent at home. Still, the emperor knew his situation was untenable in the long term: The invading forces were succeeding in taking major cities and preventing the flow of resources to the Vietnamese forces.

Negotiations for a final peace finally began in March 1862. The Mexican delegation was bitterly divided internally, some were hardcore imperalists and others just wanted an honorable exit for Mexico. About the only thing they could agree on was that, almost to a man, they were really pissed at the Portuguese, who wanted territory despite (in the eyes of the Mexicans) not contributing their fair share.

In the terms of the following Treaty of Saigon of June 1862, the Portuguese got what they really wanted: some territory in the form of the provinces of Vĩnh Long, An Giang, and Hà Tiên. The Mexicans got a guarantee of the right of Catholics to practice their religion freely and the cessation of Hanoi and some territory along the Hong River. Prime Minister Robles hoped that this would be enough to save his premiership, but when the terms of the treaty were announced, the Liberals demanded his head. Most demanded to know, “Why did Mexicans die for Protuguese gains?” Some hardline anti-imperialist even asked, “Why did we participate in the theft of Vietnamese lands? Weren’t we only there to defend the Church?” His own party was unwilling to defend him, and the Prince of the Union was forced by the Empress to withdraw his support of Prime Minister Robles and sent to Costa Rica to keep him away from Mexico City.

The attacks contributed to the fall of the Conservative control of the Chamber of Deputies following the 1861 elections. Robles retired from politics after it became clear the Conservatives (many of them the same deputies who encouraged the war at first) didn’t want him to be the face of the party in the new Chamber. He would forever defend his actions in regards to the First Mexican Intervention in Vietnam.

Even though the acquisition of Hanoi was lambasted at the times, none of his successors to the post wanted to take the potential risk of returning it to the Vietnamese and being accused of losing Mexican territory paid for in Mexican blood. Part of that calculus also came from later analysis that found that the anti-imperialists, although vocal, weren’t the clear majority of the Mexican electorate. Most of the damage done to Robles and this intervention in particular stemmed from an unpopular peace: the terms were largely unpopular because it was felt like the Portuguese got more for doing less. It’s been argued that Robles could have held on to power if he either committed to not taking territory or took more and that, overall, he was the fall guy for a larger imperialist cabal that played their hand poorly.

For her part, the Empress was reportedly appalled at the lengths the Mexican Army went to to suppress the guerillas, but she still signed the treaty. In private correspondence, she stated that she felt it was a fait accompli, that to veto the treaty would weaken the position of Mexican diplomats and reflect poorly on herself and her son. It’s not entirely without merit that some quote the words used to describe Empress Maria Theresa’s involvement with the First Partition of Poland: “The more she cried, the more she took.”

Also, sounds like Mexico did not have the best time in the Pacific. Though interestingly enough, I expected their relationship in Korea to go better, given how Christianity has more of a foothold in Korea for cultural reasons in OTL. Should still be quite a treat to see though.

Welcome back

Welcome back

Also, sounds like Mexico did not have the best time in the Pacific. Though interestingly enough, I expected their relationship in Korea to go better, given how Christianity has more of a foothold in Korea for cultural reasons in OTL. Should still be quite a treat to see though.

Welcome back

Thanks.

I thought it'd make sense for the relatively inexperienced Mexican diplomatic corps and leadership to commit mistakes on their maiden voyage. When they know what they want and who to talk to, like in Japan or Brunei, they can pull through, but when they're caught in a stickier situation, they're more prone to impatience and directionless.

They'll be back in the Pacific for sure, and when they do, they'll have learned their lessons.

Threadmarks

View all 34 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks