Epilogue: The Legacy of Buran

"Flowers Pack" by Godzilko via blendswap.com

The Buran Incident Investigation

The tragic loss of Buran and her crew in 1999 spelt the end of the Soviet shuttle programme. Already facing criticism over high costs and limited utility, the destruction of the only man-rated orbiter ruled out any near-term return to flight for the system. This grounding was soon confirmed to be permanent, with the Soviet Space Agency ruling out upgrading Burya or the other uncompleted orbiters to flightworthy status even before the cause of the accident was confirmed.

Even as the five Soviet victims of the disaster were being buried in the Kremlin wall, the investigation into the cause of the disaster was well underway. Given the high-profile nature of the disaster, the resulting accident investigation was conducted with a rigour and openness unusual in Soviet inquiries. In the light of the loss of two US citizens, NASA were invited to send a team to participate in the investigation, with the Americans given unprecedented access to Soviet records and facilities. This cooperation was reciprocated, with US resources and diplomacy being deployed to help recover wreckage from the orbiter, which was spread across remote locations in a number of north African nations.

When the investigation team published their final report in October 1999, it confirmed and ice impact on the thermal protection tiles at launch as the primary cause of the accident. Although the impact itself had not been observed, launch day footage did show large chunks of ice detaching from the Energia core, whilst instrument data recovered from the wreckage clearly showed the trouble starting at the ONI-II bay. From this information, investigators soon pruned their fault trees down to a scenario in which ice impact caused a breach in the thermal protection system close to the ONI-II hatch.

The report noted that damage from ice impacts had been identified as a risk as early as Buran’s maiden flight in 1988, but that the only mitigating actions taken had been to increase CCTV coverage at the pad to watch for ice build-up before launch. Dedicated ice inspection teams, which had long been standard for NASA shuttle launches, had been used for Burya’s 2K1 flight, but had then been dropped as the unpopular duty was considered unnecessary given the success of the initial launches. As time passed with no serious incident, the risk had become normalised in the minds of the mission directors, to the point where even the TV camera network was no longer maintained to a high standard.

Also coming in for criticism were a number of design issues that had contributed to the disaster. Foremost of these were the decision to arrange Buran’s belly thermal protection tiles in rows perpendicular to the airflow, rather than at an angle as on the US shuttle. This simplified installation and maintenance, but it made possible the formation of plasma arcs at the junction of tiles, without which the damaged ONI-II hatch may have been able to withstand re-entry. The inclusion of the hatch itself in the vital belly heat shield, which unlike penetrations for the landing gear would have to be opened before re-entry, was another area highlighted as an unnecessary risk. Also criticised was the use of unstable hydrazine in the VSU hydraulic power system, and the use of common propellant tanks for the main ODU engines and the RSU control thrusters.

Aside from these specific technical issues relating to the 1K4 disaster, the Report criticised the general state of the shuttle programme in no uncertain terms. Over the lean years of the early and mid-1990s, the shuttle’s supporting infrastructure had been allowed to degrade to a dangerous level. An in-depth review of the status of Pad 38 found several hundred potentially dangerous faults in the towers and their fueling systems, as well as at the MIK orbiter processing facilities, whilst the long periods between launches had led to a serious degradation in personnel skills. At least a dozen incidents were identified that could have led to a loss of mission on earlier flights.

In the wake of the report a number of high profile managers were arrested and sentenced to hard labour, whilst in the US, MirCorp quickly folded, becoming the subject of a Congressional hearing over their alleged “reckless” exposure of US citizens to unacceptable risks. All plans to fly future paying “space tourists” were cancelled indefinitely.

However, the NASA team felt that this punitive response failed to get to the underlying root causes, and was in fact part of the problem, contributing to an endemic culture of scapegoating within the Soviet space programme. This led to a situation in which virtually no-one (excepting the cosmonauts themselves) was prepared to take personal responsibility for their actions and how it affected overall mission success, in case they should later be penalised for problems that might arise. As a defensive mechanism, individual technicians and team leaders therefore performed only those tasks they had been specifically directed to undertake by higher authority. This American impression of a bureaucratic, box-ticking Soviet safety culture was to have ongoing repercussions on the possibilities for future joint US-Soviet space projects.

NASA Learns the Lessons

The Buran disaster was a wake-up call not only for the Soviets, but also for NASA. For several years there had be warnings from within the agency that the pressure to increase the pace of launches in order to get Alpha completed as quickly as possible was placing an unsustainable strain on the Agency and its workers. Fears that the painful lessons of Challenger were being forgotten had been largely dismissed by NASA management, but the failings uncovered by the Buran Incident Investigation shone a new light on NASA’s own practices. One area to receive particular attention was the prevailing attitude to TPS impacts.

As the BII Final Report had highlighted, NASA had long conducted dedicated anti-ice inspections before launch, and so a repeat of the ice strike that had doomed Buran was considered unlikely. However, pieces of insulating foam shaken loose from the shuttle’s External Tank had been observed impacting the orbiters on almost every shuttle launch to date. Although a number of engineers had flagged this as a potential risk to the integrity of the heat shield, there had never been a serious incident recorded, and so the risk had been classified as minimal. Now, with Buran offering a grim example of the consequences of TPS damage, the analyses and tests were repeated, and came to a worrying conclusion: in certain circumstances foam strikes could indeed cause enough damage to lead to a loss-of-mission during re-entry.

This was just one of a number of issues highlighted in a wide-ranging NASA report on shuttle safety that was published in March 2000. NASA immediately took action to mitigate the most pressing issues, including new methods for inspecting and fixing the thermal protection system on-orbit, as well as advancing existing plans to replace the shuttle’s hydrazine-powered APUs with a safer electrically powered system [1]. They also expanded the schedule for completion of Alpha in order to reduce the number of missions per year. Under the new plan, the Initial International Crew Capability, with all major European and Japanese component in place, would be achieved by early 2002. The Common Core/Habitation module (a virtual copy of the “Destiny” Common Core/Lab with dedicated crew support facilities) would be now launched in mid-2003, whilst the development of a US replacement for the Soyuz-ACRV lifeboats would be accelerated, allowing the expansion of the permanent crew from three to six to take place in 2004.

However, a decision on the most important issue - the long-postponed development of a safer successor to the shuttle - was held off until the arrival of a new NASA Administrator under a new President in 2001.

Moving On from the Disaster

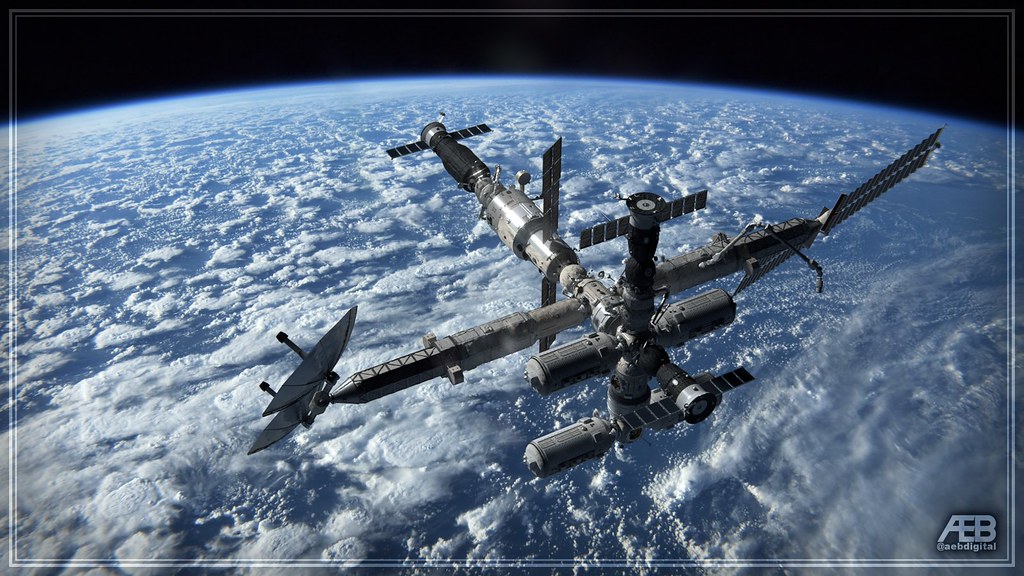

Despite the terrible grief felt throughout the Soviet space programme at the loss of their comrades, to a large extent most of VKA’s ongoing projects remained unaffected. The huge expense of the shuttle system meant that it had already been largely decoupled from the ongoing Mir-2 programme, and the reliable Soyuz and Zenit rockets continued to send crews and cargo to the station despite the loss of Buran. Plans to complete the assembly of Mir-2 were slowed as schedules were reassessed and funds were re-prioitised to long-delayed ground infrastructure upgrades, but despite this the launch via Zenit of ESA’s Magellan module went ahead as planned in April 2000. Later the same year a modified Progress M2 spacecraft delivered the second airlock module, SO-2 “Poisk”, to the station, with the first lab module, “Nauka”, delivered in May 2001. It was at this point however that the loss of the shuttle’s heavy lift capability made itself felt.

To expand Mir-2 further, the station would need more power. This was originally planned to be provided by a second truss section, NEP-2, mounting two large “solar dynamic” parabolic dishes that would focus sunlight to heat a working fluid and drive a turbine, offering improved power-to-weight performance compared with photovoltaic arrays. This large, complex system was intended to be delivered by Buran just as NEP-1 had been, and although it had been designed with the possibility of splitting it between several Zenit launches, the implications of actually having to do this were giving programme engineers and managers severe headaches. However, it was soon realised that there was another possibility: Energia.

Energia’s Last Hurrah

The Energia carrier rocket for the next planned Buran mission, vehicle 8L, had already been 90% completed at the time of the loss of Buran. Although the assembly lines for new Energia cores were being shut down by 2000, the teams and material needed to complete the 8L core were still in place at Baikonur, allowing the final vehicle to be assembled at relatively little cost. A proposal was quickly put together at RKK Energia to use this core as the basis for an unmanned, cargo-only version of the booster. Initially this was planned to be the long-discussed Energia-M variant, but it was quickly decided to instead simply use larger Energia-T configuration. Although massively over-sized to deliver NEP-2 to orbit, Energia-T would require virtually no modifications to the 8L vehicle.

To place NEP-2 into orbit and guide it to a docking with the space station it would be necessary to provide a space tug. NEP-2 was far too massive to be carried by a Progress M2 service module, and so Soviet engineers turned back to the solution they had used for the very first Energia launch in 1987: Chelomie’s venerable TKS. The last of the 77K modules originally built for Mir, 77KSI, was dusted off at Fili KKP and in early 2001 renovations began to turn it into an autonomous space tug.

Energia-T2 (the initial launch having been retrospectively designated as T1) was finally rolled out to Pad 38 in May 2003. This final lift-off on 8th May completed a perfect record of eight successful launches out of eight for Glushko’s giant rocket, in stark contrast to the record of the N-1 launcher that it had been designed to replace. Unlike the case in 1987, this time the TKS-derived space tug operated correctly, no doubt helped by its more traditional placement at the bottom of the payload stack rather than at the top, facing downwards. 77KSI successfully inserted NEP-2 into a low parking orbit before initiating an orbital trajectory that would see it rendezvous with Mir-2 two days later.

The first docking attempt on 10th May was aborted due to a spurious accelerometer reading. This was later found to be an instrumentation fault, but mission controllers were taking no chances. NEP-2 by far the heaviest payload ever to attempt an automatic docking as the active partner, and with its many modules and appendages Mir-2 presented a complex target. However, the second attempt on 11th May was successful, with NEP-2 easing in to soft-dock at Yedinstvo’s axial docking port. Two days later, its job completed, 77KSI detached from NEP-2 and was commanded to a destructive re-entry, whilst at the station cosmonauts Usachev and Malenchenko, together with ESA guest cosmonaut Léopold Eyharts, used the European Robotic Arm to move NEP-2 to its final location opposite NEP-1 on Yedinstvo’s Y+ mid-point docking port. Within a month the new module’s solar furnace would begin supplying power to the station, finally providing the resources needed to support the completion of the station.

Looking to the Future

As of 2005, with Space Station Alpha fully assembled and Mir-2 nearing completion, thoughts are turning to the next step in humanity’s exploration of space. With the Soviet economy booming on the back of high oil prices and the US and Western Europe enjoying a period of sustained growth, there appears to be a rare convergence of political ambition and financial means.

For the US, the most significant development has been the decision by the Bush administration to refocus NASA’s efforts to rely more upon the commercial sector. In 2002 NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe announced that, following the deployment of the Horizon ACRVs to Alpha [2], NASA would aim to transfer logistical support for the station to the private sector by 2010, using unmanned vehicles launched via the new Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicles and other commercial rockets, including the European Ariane and Soviet Zenit.[3] With cargo launches thus outsourced, the aging and expensive Space Shuttle would finally be retired, with its role in launching American crews into space taken up by a new Crewed Space Vehicle. Although a derivative of Lockheed’s Horizon spaceplane is considered a front-runner, its selection is far from guaranteed as, in a departure from NASA’s usual procurement methods, the CSV uses an innovative spiral development programme. This sees fixed-cost milestones replacing the more traditional cost-plus approach, culminating in a fly-off of the two most promising designs in 2009. As well as supporting LEO crew rotations of up to seven astronauts, the CSV is also expected to replace Horizon in the role of Alpha’s lifeboat. More ambitiously, CSV is being designed to support missions further into space, carried aloft by a new Energia-class launcher, the so-called Shuttle Derived Launch Vehicle (SDLV). Currently undergoing Phase-A studies, but planned to launch as soon as 2012, the SDLV will open up the possibility of a return to lunar orbit, to be potentially followed by lunar space stations and renewed landings by 2020, depending on future budget allocations.[4]

As has often been the case throughout the history of manned spaceflight, Soviet plans to a large extent mirror those in the US. Even before Buran’s first flight, the Soviets had been considering developing a large capsule-based crew vehicle to replace Soyuz. In the tumultuous economic circumstances of the late ‘80s and ‘90s these plans had been put on hold, but with the loss of Buran and the improved economic situation in the USSR they have been revisited. In 2003 the Soviet Space Agency confirmed plans to push forward with development of a modernised version of the Zarya reusable space capsule that had first been proposed in the late ‘80s. Launched by Zenit, Zarya would carry twice the crew of Soyuz and would be designed from the start to support future deep space missions.

In parallel to the Zarya decision, the Soviets were also considering the development of a new family of heavy lift rockets to finally replace Proton whilst matching the capabilities of the SDLV. Although the initial proposal from RKK Energia was to once again push for Energia-M, VKA felt that the expensive infrastructure needed to support the large hydrogen-oxygen core stage, as well as the lack of flexibility to scale down the design for smaller payloads, made this unattractive. Instead they announced in 2004 plans for a new Zenit-derived all-kerolox rocket system named “Don”.[5] By clustering one, three or five Zenit-style boosters with a kerolox upper stage, the Don system would be scalable, with the largest variant matching SDLV, being able lift up to 63 tonnes to Mir-2’s orbit.

Talks are already underway between NASA, VKA and ESA about the opportunities these new developments may open up. Ideas for an international lunar programme are being floated, including a jointly built Lunar Orbital Station, or even a surface Moonbase supported by US and Soviet landers. Further ahead, Mars beckons, with Soviet and American scientists investigating nuclear powered ion drives and in-situ resource utilisation technologies that might allow a manned expedition as soon as 2025. After more than thirty years stuck in low Earth orbit, humanity is once again turning outwards towards the manned exploration of deep space.

The Shuttle in Perspective

The Soviet space shuttle programme was created at the height of the Cold War as counter-move to a threat from the US shuttle that wasn’t fully understood and which never in fact existed. Militaristic fantasies of the Americans using their shuttle to bomb Moscow or pluck Soviet space stations from orbit drove the Communist leadership to order their own version to maintain the balance of power, but beyond this they had no real vision for how the shuttle would be used. Energia’s Chief Designer in the 1970s, Valentin Glushko, saw the shuttle as merely one more payload for his giant, Moon-aimed rocket; something to persuade the military to pick up the bill rather than being an objective in its own right. As well as the expense and technical complexity of the system, it is this status as a solution in search of a problem that helps to explain the long delays in getting Buran and Burya into space. With the end of the Cold War in 1989, it became even harder to justify the enormous costs needed to maintain a system that never managed to truly match its American rival in flight rates or usefulness, flying only six times in total. In the light of the Buran disaster it’s easy to castigate the programme as an unjustifiable and senseless waste of both money and human lives. And yet…

Despite all of their shortcomings, all of their costs and tragic consequences, these elegant spaceplanes had an undeniable romance to them. Even when times were hardest, as during the 1990 coup or the 1995 financial crash, surveys of Soviet public opinion repeatedly found large majorities in favour of keeping the shuttles flying. In their turn, Soviet space planners spared no effort to somehow find the resources needed to keep the shuttles flying, even at the cost of robbing Peter to pay Paul. With every launch, Buran and Burya proved that the Soviet Union was still a world-class power, justifying their people’s pride. The shuttles were not just spacecraft; they were national heroes, beacons of hope. Even today, if you visit Moscow’s Museum of Cosmonautics, you will find large crowds of adults and children flocking to see Burya up close, imagining themselves at the controls as fearless cosmonauts exploring the universe.

Buran is gone, but her dream lives on.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

[1] There were plans IOTL post-Columbia to replace shuttle’s hydrazine APUs with electrical units (called the

Advanced Hydraulic Power System, AHPS), but the decision was apparently postponed until the planned retirement of the system made it moot. Here, with the APUs being a major contributing factor to Buran’s demise, and with a softer retirement date for the shuttle ITTL, NASA and its overseers in government place more emphasis on getting this upgrade done.

[2] Horizon a lifting body based upon OTL’s X-38. The decision to go ahead with a space station without long-term Soviet involvement meant that the US committed to developing their own lifeboat for Alpha in 1994. This programme used funds that IOTL were spent on the X-33 project, which does not exist ITTL.

[3] This is a combination of the OTL Orbital Space Plane and Crew Exploration Vehicle/Orion, tending more towards the former than the latter. The overall programme borrows a lot from OTL’s Vision for Space Exploration (especially the free-market friendly leveraging commercial space aspects that Griffin largely ditched IOTL to pursue “Apollo on steroids”), but with less emphasis on the Moon as a firm target. Without OTL’s Columbia disaster, there’s less of an impression that NASA needs radical redirection.

[4] Yes, this is basically Shuttle-C/NLS/Ares-V/DIRECT Jupiter/SLS. What, you think there’s any chance whatsoever that Congress is going to allow the shuttle to be retired without funding a replacement jobs programme? ASB! As with its various OTL incarnations, don’t put too much emphasis on the planned launch dates - to its government sponsors, its success as a programme is measured more in people employed (and votes received) than in missions flown.

[5] This is basically a version of the

Sodruzhestvo rocket proposed IOTL, or indeed the recently announced

Energia 5VR.