Mission 1K4: Buran-Mir-2, March 1999

Space Truckers

By 1999 Low Earth Orbit had become a busy construction site, in which winged shuttles were finally able to fulfill the role envisaged for them since before the dawn of the Space Age: orbital trucks, hauling the cargo and supplies necessary to assemble and maintain large, permanent space stations. The US was leading the way, as starting with the launch of Atlantis on STS-86/Alpha Assembly Flight 1 in September 1997, the Americans used their shuttle to first build an unmanned “Power Station” before going on to develop a man-tended capability with the addition of the first Common Core/Lab pressurised module (“Destiny”) [1] on STS-90/AAF-4 in June 1998. Less than one year later, in May 1999, Alpha reached its Initial Permanent Crew Capability, with Discovery delivering the first of two Soviet-built Soyuz-ACRV lifeboats to the station on mission STS-93/AAF-4a. With this addition the crew of Alpha Expedition 1, James Voss and Ellen Ochoa, began a permanent US crewed space presence which continues to this day. With this milestone achieved, attention next shifted to providing an “Initial International Crew Capability” through the addition of the European Columbus and Japanese Kibo modules. Assuming no unexpected problems arose, NASA was on course to achieve their objective of a permanent crew of six before the end of 2002, when AAF-13 was scheduled to deliver the second Soyuz-ACRV.

In comparison, the Soviets had placed much more emphasis on unmanned launchers to support the assembly of their space station, reflecting their previous experience with Salyut and Mir. While NASA’s fleet of four shuttle orbiters were supporting five or six assembly flights per year, VKA’s single operational orbiter, Buran, was assigned to carry only the largest and most complex components for Mir-2, where the shuttle’s heavy lift capability and support for complex human-guided operations would have the greatest value. The first such mission came in March 1999 with the launch of mission 1K4.

Following her flight to Mir in mid-1997, Buran had undergone a comparatively rapid and trouble-free turnaround, and was ready to support another mission as early as December 1997. Her carrier rocket, Energia vehicle 7L, was not far behind, with all components integrated at Baikonur in January 1998. However, on this occasion the problem was with the payload. The two large Science Power Platform trusses (“Nauchno-Energeticheskaya Platforma”, or NEP) had been starved of funds during the financial crisis as meagre resources were diverted to the critical initial modules of the station. The design was not finalised until late in 1995, with construction only starting at RKK Energia in early 1997.

The main assembly of NEP-1 did not arrive at Baikonur’s MIK 2B payload processing facility until October 1998. This consisted of a pressurised module containing gyrodynes and control systems; a fixed truss containing batteries, propellant tanks and a deployable radiator; and an extending truss section terminating in the solar array drive assembly. The solar panels themselves were stowed in separate packages tied to the side of the truss, to be unpacked and connected by spacewalking cosmonauts. Folded tightly against the side of the truss were the two VDU propulsion units, larger versions of the experimental unit that had been tested on Mir’s Sofora truss. The final item to be shipped with the NEP was the ESA-supplied European Robotic Arm (ERA), which had been delivered to the Soviets earlier in the year. ERA was an important part of plans for Mir-2 as it would enable the repositioning of heavy station modules and other payloads when Buran and its twin SBM manipulators were unavailable.

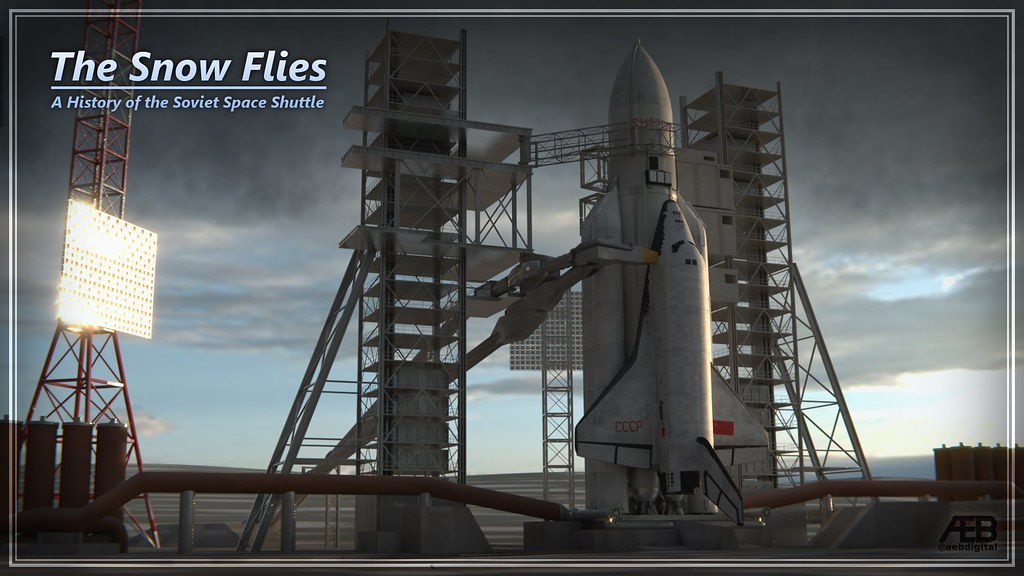

Integration and testing of the NEP-1 package proceeded over the following two months before the entire assembly was moved to the MIK RN and carefully lowered into Buran’s cargo bay. At almost 22 tonnes, NEP-1 was by far the heaviest payload yet for the Soviet shuttle, and together with the SM docking module completely filled the orbiter’s cargo bay. [2] In an unusual step, fuelling of NEP-1’s propellant tanks was carried out in the MZK along with Buran’s own on-board propellant loading. This was done in order to minimise the amount of time that the poisonous UDMH/N2O4 propellants would be present in the stack, necessitating special precautions when working on the spacecraft. With this hazardous task completed, the payload bay was re-sealed and the Buran/Energia-7L stack rolled out to Pad 38 for final preparations and fueling of the Energia rocket.

Controversial Crew

One positive aspect of the enforced delay in launching mission 1K4 was that it gave time for the necessary remodelling of Buran’s mid-deck Habitation Compartment to allow the fitting of ejection seats in the BO. The number of crew members carried could therefore be expanded beyond the initially planned four, to potentially as many as ten. In the end however, it was decided to include only three additional crew members, bringing the total up to seven (coincidentally the normal maximum crew complement of the US space shuttle).

Commanding the spacecraft would be Ivan Bachurin, who had been part of the GKNII-1 group of pilot-cosmonauts selected for the shuttle programme back in 1979. Piloting Buran would be Valeriy Maksimenko, a member of the 1990 GKNII-4 intake of cosmonauts, with the remaining two flight deck seats taken by TsPK flight engineers Valeriy Illarionov and Sergei Avdeyev. Taking the first of three seats in the BO was Vladimir Dezhurov, veteran of Mir expedition EO-18 during which Buran had docked with the station on mission 1K2.

The next seat was assigned to NASA astronaut Jerry Linenger, whose participation in the mission was part of a series of US-Soviet crew exchanges that had been agreed to alongside the signing of the contract for Alpha’s Soyuz-ACRV lifeboats back in 1994. The programme had previously seen astronaut John Blaha visit Mir on Soyuz TM-24 in 1996 (to be picked up by the shuttle Atlantis later that same year) and cosmonaut Yelena Kondakova join the crew of Columbia as part of STS-83 in 1997. Linenger had originally been planned to fly to Mir-2 aboard Soyuz TMA-5, but the opening up of mid-deck seats on Buran was an opportunity that neither the Soviets nor NASA wanted to pass up, and he’d switched to training for 1K4 in mid-1998.

Linenger’s participation in the mission had however been put into some doubt when NASA discovered who was to fly in Buran’s final available seat: MirCorp investor and the world’s second space tourist Dr. Chirinjeev Kathuria. NASA (with no apparent sense of irony) considered the Soviets’ commercial sale of berths on their spacecraft to private individuals to be in some way demeaning to NASA’s own state employed astronauts. The announcement that Indian-American businessman Kathuria would be sharing a ride with Linenger caused some diplomatic tension between Washington and Moscow in the winter of 1998/99, with pressure also being applied to US-based MirCorp to withdraw from the mission.

Despite the fact that many in the Soviet space programme privately agreed with NASA’s view, in the end these efforts came to nothing, and the American agency grudgingly accepted Kathuria’s presence on the mission (though they insisted on referring to him as a “citizen astronaut” in NASA press briefings, while everyone else continued to use the term “space tourist”).

Journey to Mir-2

Buran experienced a trouble-free launch on 20th March 1999. The surplus of time available for pre-flight servicing, combined with the heightened media attention surrounding the launch of Linenger and Kathuria, meant that there had been a special focus on quality during pre-launch processing of the orbiter and and its launcher to ensure no embarrassing systems failures would marr the mission. In particular, the word came down from the central government that any repeat of the engine trouble seen on mission 1K3 would result in criminal prosecutions of all involved. This crude threat appeared to have the desired effect, as 1K4 went on to have the fewest number of reported anomalies from any Energia launch to date.

Once on orbit, the seven-man crew were able to stretch their legs, with Buran’s accommodations easily able to support the enlarged crew. Whilst Bachurin and Maksimenko were occupied with putting Buran on a trajectory to intercept Mir-2, Illarionov and Dezhurov busied themselves by checking out the shuttle’s NEP-1 payload. Avdeyev and Linenger were tasked with activating the experiments hosted in the BO, whilst Kathuria made himself useful performing various housekeeping tasks, alongside his main objective of filming promotional videos for MirCorp’s publicity efforts. For sleeping arrangements, Bachurin and Maksimenko both remained in the KO, with all of the other cosmonauts sharing accommodations in the BO.

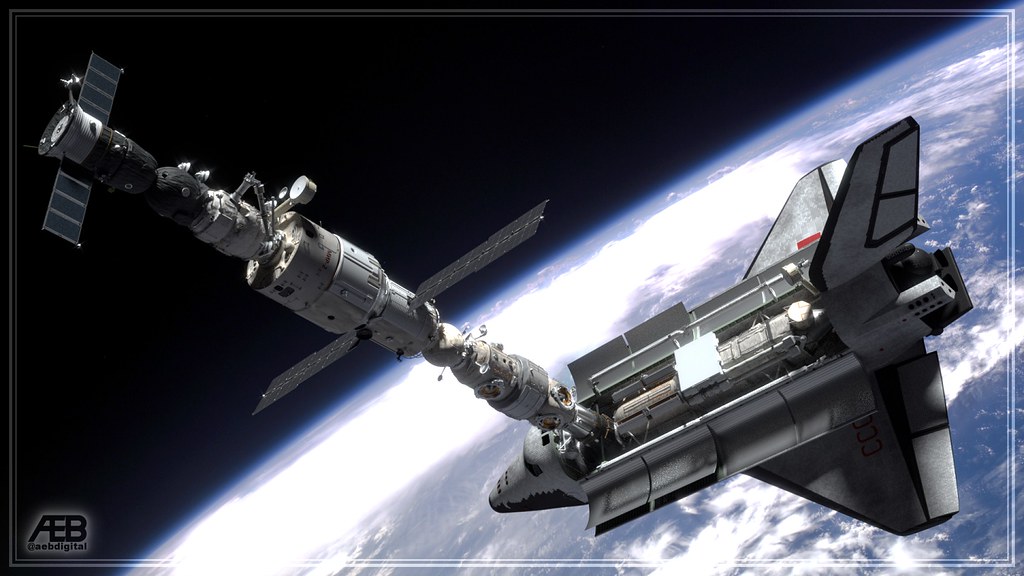

On the morning of 22nd March, Buran was ready to make its final approach to the new Soviet space station. After making a brief fly-around of the station, Bachurin lined the shuttle up with the APAS-89 port of it’s SM facing the axial port of the Yedinstvo module. During final approach Mir-2’s resident crew, Vasily Tsibliyev and Aleksandr Kaleri, retreated to their Soyuz TMA-3 spacecraft, but remained docked to the station, ready to separate only if an emergency demanded it. In the event their caution was not needed, as Buran gently nudged up to the station. Thirty minutes after hard-dock, the two crews greeted one another in Yedinstvo, forming the largest on-orbit crew of any space mission to date [3].

Putting it All Together

The next few days saw Mir-2 become a hive of activity, starting with the removal of NEP-1 from Buran’s cargo bay and its attachment to Yedinstvo’s Y- mid-point docking port on 23rd January. With docking confirmed good, Kaleri entered the NEP’s pressurised module and commanded the full extension of its truss, ready to receive the solar arrays. This relatively straightforward task was then followed by one of the most complex EVAs ever attempted, as Bachurin and Illarionov exited Buran’s SM airlock whilst Dezhurov and Kaleri egressed the Pirs docking module, with Maksimenko controlling Buran’s two SBM arms from the Command Compartment to move the four spacewalkers to the newly installed NEP-1 truss. Over twelve hours, this record-breaking spacewalk saw the VDUs deployed and the solar arrays connected to the rotary joint at the end of the truss.

The next day saw the NEP’s radiator deployed and internal connections made, before Kaleri and Illarionov once again ventured outside the station on 25th January to wire up the solar panels and run external mechanical and electrical connections between the NEP and Yedinstvo modules. With this task completed after an exhausting 8-hour spacewalk, NEP-1 was finally given the command to unfurl its solar wings and began feeding 40 kW of electrical power into the station’s systems.

While the Soviet cosmonauts focussed on expanding their station, NASA astronaut Linenger spent most of his time installing and tending experiments in the Mir-2 Base Block. These were primarily related to human health and space environment issues, designed to provide comparable datasets of human reactions aboard both Mir-2 and Alpha. An example of this was the IREX experiment, which was designed to measure the radiation environment within Mir-2 whilst a similar detector installed on NEP-1 would relay measurements from outside the station. Identical instruments were already in place aboard Alpha’s Destiny module and S1 truss, allowing scientists and engineers to directly compare how the different orbits and construction of the two stations affected the radiation fluxes experienced by the crews.

Although the results of this and other experiments were received positively, Linenger himself proved to be a more disruptive element. With electrical power aboard the station limited before the deployment of the NEP-1 arrays, the US astronaut found his activities frequently disrupted by power shortages. Also frustrating was the Soviet approach to undertaking mission tasks on a largely ad-hoc basis, in stark contrast to the detailed timelines and procedures defined by NASA for its astronauts. Any activity that required the support of the Soviet cosmonauts was subject to their own, often shifting priorities, which played havoc with Linenger’s carefully crafted schedules. The fact that the American astronaut was not shy in voicing his displeasure did nothing to encourage his Soviet comrades to go out of their way to help him.

Nor did it help that Linenger managed to alienate his only other potential assistant, space tourist Dr. Kathuria. Kathuria had early on volunteered to support Linenger with any routine, non-specialist tasks, only to be sharply rebuffed. Part of this was a reflection of NASA’s official disapproval of space tourism, but part seemed to have been a simple personality clash. In either case, the result was Kathuria devoted more time to his promotional activities and Earth-watching, whilst Linenger fell further behind in his scheduled activities.

Back to Earth

After five days docked to the station, Buran’s crew of seven re-boarded the shuttle and prepared for departure. The mission had been by far the most intensive of any previously flown by the Soviet shuttle, setting new records for the number of man-hours of EVA in such a short period. Despite their exhaustion though, the crew of 1K4 could look back with satisfaction at a job well done, with the fruits of their efforts clearly visible as the shuttle pulled away from the station. Mir-2 had gone from a small collection of linked modules into a true building in space, a complex structure spanning almost 30 metres, capable of supporting the new laboratories now under preparation on the ground. The next Buran mission was scheduled to complete the station’s main truss with the addition of NEP-2, and with the Soviet economy finally starting to turn around there were expectations that the tempo of shuttle missions might finally increase to something resembling a regular service. Old plans for long-duration, high altitude orbital missions with the shuttle were being dusted off in Kaliningrad as programme managers dared to hope that Buran may fly twice a year or more from 2001 onwards.

It was not to be.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

[1] The Common Core/Lab modules are - literally - a merger of the planned Freedom Resource Node and Lab modules, which substitute the Forward Cylinder of the Lab module with a Node Radial Port Cylinder. This was part of the 1993 Space Station Redesign Report’s Option A, intended to save money by building just one type of US pressurised module instead of the two planned for Freedom.

[2] IOTL the version of the NEP that was planned for the ISS came in at around 15 tonnes on launch and 20 tonnes when all its extra systems were installed. TTL’s NEP is larger and manages to squeeze all of the necessary systems into a single launch. The SM docking module masses around 3.5 tonnes, meaning Buran will on this occasion be carrying 25.5 tonnes out of a designed 30 tonne maximum payload. According to the

Guinness Book of Records, the largest OTL shuttle payload was the Chandra X-ray telescope at 22.8 tonnes, so it seems likely that Buran mission 1K4 will take the record for the heaviest ever shuttle-launched payload.

[3] IOTL the record is thirteen people aboard the ISS via missions STS-127, Soyuz TMA-14 and Soyuz TMA-15 in 2009. ITTL the previous record was the eight person crew of STS-61-A in 1985, although there have almost certainly been more people on orbit at once (but not docking, so not forming a single crew), as happened in 1995 IOTL when thirteen people were on orbit with Soyuz TM-20 and -21 docked at Mir during STS-67. ITTL, Alpha’s current minimal volume (one pressurised module only) means its maximum crew is currently limited by how many supplies can be squeezed in with the crew, so although the Soyuz-ACRV could allow up to three people, Alpha will have an initial permanent crew of two.