Book VIII: Of Spinning Plates

Mens regnum bona possidet - "His own desire leads every man"

Uxor formosa et vinum sunt dulcia venena - "Beautiful women and wine are sweet venom"

Arcadius, eldest son of Theodosius, ascended to the sole rulership of the Eastern Empire in 395. Like his brother Honorius in the West, Arcadius was de facto subordinate to a number of powers behind the throne. Initially this was Rufinus, a statesman of Gaulish ancestry. Rufinus' tactics in many ways mirrored those of Stilicho, the half-Vandal general who was the power behind Honorius in the West. Rufinus attempted to marry his daughter to Arcadius, but was unsuccessful, with his rival Eutropius orchestrating the marriage of Arcadius with the beautiful Aelia Eudoxia, daughter of Flavius Bauto.

The rivalry between Rufinus and Stilicho obstructed cooperation between the two halves of the Empire. Rufinus believed that Stilicho intended to exert control over Arcadius as well as Honorius, becoming in effect the sole ruler of the Roman Empire. Stilicho distrusted Rufinus as a dangerous schemer, and doubted his loyalty to the Empire above his person. In the winter of 395, Rufinus was killed by the forces of the Gothic mercenary captain Gainas, working in the employ of Stilicho.

With the death of Rufinus, the eunuch Eutropius replaced him as the puppeteer behind Arcadius' throne. In 397-8 a Hunnic invasion ravaged the countryside of Cappadocia, whilst Isauria saw yet another uprising by the fiercely stubborn natives. Although these attacks were suppressed by the end end of 398, they underlined the relatively weak leadership of the Eastern Empire. As a result of the initial slow response to the Hunnic incursions, the

magister militum Leo was replaced by Gainas. Whilst Gainas fared little better, he blamed

cubicularius[24] Eutropius. Gainas installed his forces in Constantinople and had Eutropius, who had recently been dismissed by Arcadius at the advice of Eudoxia, executed. Many others were to be executed, but they were spared after the intervention of St. Ioannes Chrysostom. Gainas was unable to maintain control of the capital. The locals rioted, spurred to action by Empress Eudoxia. The viciously anti-Arian Roman populace surrounded and trapped 7,000 armed Goths, tearing them apart limb-from-limb. Gainas fled and escaped across the Danube to the Thervings. The Therving King Alareiks [25] had Gainas killed and his head sent to Arcadius, seeking to maintain a friendly relationship with the Romans. In 399, Eudoxia and Chrysostom also had Arcadius issue an edict calling for the demolition of all remaining non-Christian temples, yet another blow to the dwindling traditions of Roman paganism, as well as the cults of Sol Invictus and Mithras.

Despite this convergence of interests, relations were poor between the powerful empress and the eloquent archbishop of Constantinople. Ioannes had been embroiled in a feud with Theophilus, the Patriarch of Alexandria, who had disciplined four Egyptian monks, the so-called 'Tall Brothers' over their support for the teachings of Origen Adamantius. The four monks had fled to Ioannes in Constantinople, which was perceived by Theophilus, who coveted the city, as implying Chrysostom's support for Origen's doctrine. Eudoxia allied with Theophilus, perceiving Ioannes Chrysostom's denunciation of extravagant female clothing as an insult directed at her person. The enemies of Chrysostom, foremost amongst them Eudoxia and Theophilus, gathered in the Synod of 403 (also known as the 'Synod of the Oak') and condemned Ioannes, deposing him from the position of Patriarch. But as soldiers came to take him from the city the next day, an accident in the imperial palace led Eudoxia to think God was warning her not to mistreat the former archbishop. He was immediately recalled, re-entering Constantinople to the cheers of the people. Chrysostom would later be exiled in 404 AD, when his rivals once again got the upper hand. His last words, dying on the road to exile, were "glory be to God for all things!".

Some pious Christians believe that Eudoxia was punished by God that year, for she fell ill and deteriorated rapidly, dying that same year. With his strong-willed wife dead, Arcadius then came under the influence of the Praetorian Prefect of the East, Flavius Anthemius. In 406, Anthemius was elevated to the position of patricius. Anthemius was an effective governor of the Eastern Empire, containing the Isaurian insurgency and securing many of the borders. He passed a number of laws to silence Jews, pagans and heretics. He also supported anti-Germanic policies, in the interests of maintaining the stability and integrity of the Eastern Roman Empire. Tensions occasionally flared with Stilicho, who sought Western Roman control over the prefecture of Illyricum. In 408 Arcadius, an Emperor who cared more about his image of piety than the governance of the Empire, passed away silently into the void, silenced as always by the stories of more forceful personalities.

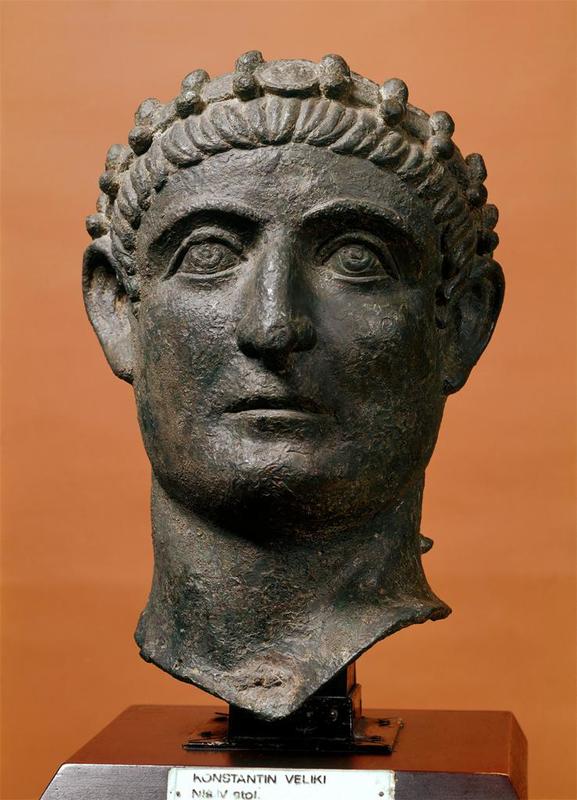

The Emperor Honorius upon his accession

When the young Emperor Honorius took to the throne in Mediolanum, Stilicho performed the role of regent. Tying himself into the House of Theodosius, Stilicho married his daughter, Maria, to the young

Augustus. He would later also marry his second daughter, Thermantia, to Honorius after Maria died of sickness in 408. A weak personality like his half-brother Arcadius, Honorius was also influenced by the Popes of Rome, who sought influence and power through association with the young, impressionable ruler. For example, in 407, Pope Innocent I had Honorius write to Arcadius condemning the exile of Ioannes Chrysostom.

The first crisis Honorius' rule faced was the Gildonic revolt in Africa. In 398 the

Comes Africae Gildo revolted against Western Roman rule, incited by Eutropius. Since the division of the Empire, North Africa had become the key granary for Rome. Gildo sought to join the Eastern Roman Empire, prompting the response by Stilicho, who used Gildo's tyrannical rule as an excuse for military intervention. 5,000 Gallic veterans under the command of Gildo's brother Mascezel landed in Africa. They were opposed by 70,000 men of the African legions, but a number defected to Mascezel's armies, leaving the two forces roughly even. Over the next year, the loyalists gained the upper hand, finally defeating Gildo near Hadrumentum in August 399. Britain also saw a small-scale invasion by the Picts, who were fought off.

Another crisis was experienced on 31 of December of either 405 or 406, when a large force of Alans, Vandals, Quadi and Burgundar crossed the frozen Rhine into Gaul. Although the historical record is uncertain, it is believed that Stilicho may have intended to make an accomodation with the barbarians to settle in Gaul if they maintained loyalty to the Roman state. More problematic were a number of revolts in Britain. In 406, the legions in Britain proclaimed a soldier named Marcus Emperor as a reaction to increasing frequency of raids by Hibernian pirates (led by King Niall Noígíallach), Saxons and Picts. Marcus quickly proved himself unpopular, and was killed in favour of his successor Gratianus. The troops in Britain became increasingly concerned that the barbarians that had fanned out into Gaul would cross the

Oceanus Britannicus. Gratian refused to move into Gaul, telling the army to stay on the island and prepare to defend it. The army disagreed, and Gratian was too killed, to be replaced by Flavius Claudius Constantinus, also known as Constantinus III.

Constantinus III moved into Gaul, landing at Bononia and taking control of swathes of Northern Gaul. The vanguard of the usurper's forces, led by Iustinianus and the Frank Nebiogastes were defeated by Sarus (a Gothic foederati leader and exile from Greuthung). This proved only a temporary setback. Constantinus sent another army headed by Edobichus and Gerontius, forcing Sarus to retreat back to Italy through passes held by

bagaudae[26]. Constantinus secured the frontier along the Rhine and garrisoned the passes of Transalpine Gaul. By the middle of 408, he had set up his capital in Arles, appointing Apollinaris as prefect.

Honorius' armies had begun to assemble in Italy in preparation for a counterattack, but Constantinus feared an assault from Hispania, where the House of Theodosius enjoyed it's strongest support. His forces mounted a preemptive assault on Hispania. Constantinus elevated his eldest son, the monk Constans to

Caesar or co-Emperor and sent him with the general Gerontius over the Pyrenees. Gerontius' forces easily defeated Honorius' cousins who commanded the legions in Hispania. Constans left his household in Saragossa to report to Arles. Meanwhile, a mutiny by the loyalist Roman army at Ticinum[27] orchestrated by Stilicho's political opponents led to his capture and execution, as well as the murder of his son Eucherius shortly afterwards. Having seen all this unfold (and experiencing Honorius' refusal to promote him to Stilicho's position of

magister militum), Sarus abandoned the Western Roman armies with his men. Left without any significant military forces at hand, Honorius recognised Constantinus as co-emperor and they shared joint consulship in 409.

By September 409, Constantinus' success was being eroded. The tribes that had crossed the Rhine had finally overrun the Roman defenses, plundered their way through Gaul and crossed into Hispania, where they allied with Constantinus' general Gerontius against his former liege. Saxon raids on Britain and the Northern Gallic coastline became increasingly pronounced at this time, leaving the British inhabitants of Armorica and Britain to expel imperial officials and effectively declare independence. Meanwhile, Constantinus made a final gamble by invading Italy with his remaining troops. The invasion was unsuccessful, and Constantinus had to retreat to Gaul in the late Spring of 410. Constantinus' forces were defeated by Gerontius' at Vienne in 411, where his son Constans was killed. His Praetorian Prefect Decimus Rusticus, who had replaced Apollinaris, abandoned Constantinus for Jovinus' rebellion in the Rhineland. Gerontius proceeded to lay siege to Arles, with Constantinus trapped inside.

At long last, Honorius had acquired a competent general capable of counter-attacking the rebels. The general Constantius (not to be confused with Constantinus) put Gerontius to flight and himself besieged Arles. Constantinus held out inside the city, waiting for Edobichus to return from Northern Gaul with Frankish soldiers. But when Edobichus did return, he was soundly defeated by Constantius' forces. Constantinus finally surrendered when his last troops along the Rhine defected to Jovinus. Although Constantius had ensured Constantinus' safety, the usurper was in fact beheaded on his way to Mediolanum in 411.

===

[24] Palace chamberlain.

[25] Alaric I.

[26] "Brigands"

[27] Pavia