Chapter Twenty: The Presidency of James Madison, 1817-1821

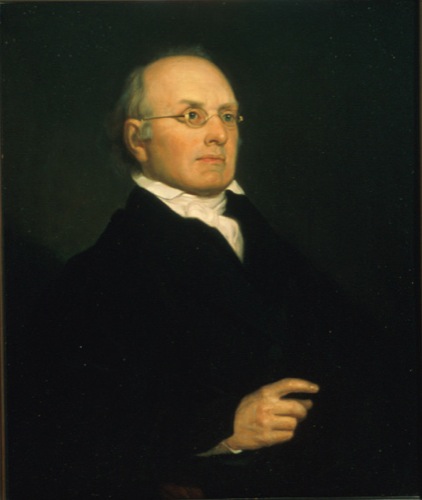

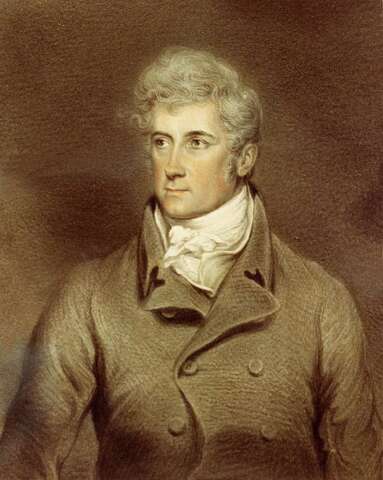

President James Madison

When Madison won the election of 1816, he was prepared to assume the office that had been denied to him in 1812 by a careless elector. In the course of four years, however, America had changed drastically. Increasingly, power was shifting out of the hands of the Revolutionary War generation, and into the hands of a new one that had yet to be defined. In all prior presidential cabinets, there had been at least three veterans of the American Revolution included. Madison's cabinet would be the last to follow this trend. In fact, it would be the last to have veterans of the American Revolution present at all. This occurrence in Madison's administration would lead to his administration being labeled as the final one of the Founding Era.

A photograph of four generations of Americans

The changing of America's era can also have been in seen in the focus of the Madison administration. While the most of presidencies of Washington, Adams, and Jefferson had been focused on establishing the U.S. government into a solid and stable body and garnering the respect of international nations, Madison's presidency differed. All of this had been pretty through established by the time Madison entered office, and he could look towards internal improvement. Under his watch, many roads, canals, and other like things were built. Prominent among these projects were the Erie Canal, which linked New York City to the Great Lakes, and the National Road, which served to connect the tradition 13 U.S. states to the Midwestern ones, providing settlers with a more stable route west. He would also oversee the creation of the Second Bank of the United States. The First Bank's charter had failed to be renewed when the Democratic-Republican controlled Congress failed to pass it, denying President Jefferson the opportunity to renew it. Under Madison, the bank would be given a second life, with Albert Gallatin, a close friend of Madison and former secretary of the treasury, serving as its first president.

A modern photograph of the building in which the Second Bank was located and a photograph of Albert Gallatin from 1848

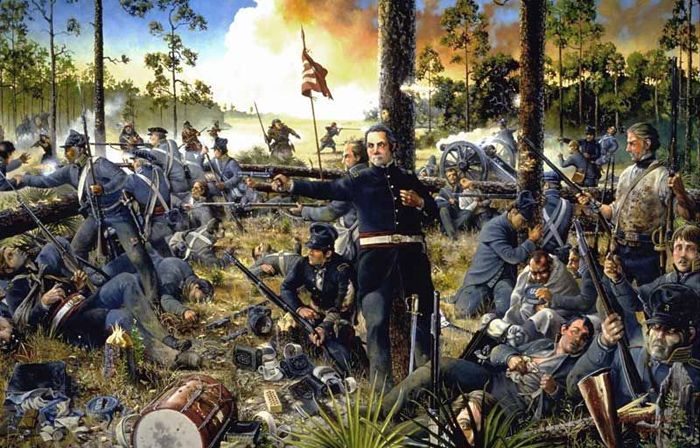

Ultimately, however, it would not be these issues that defined the Madison's term in office. Rather, it was for two other events that he is mostly remembered for. First would be the Panic of 1819. This financial depression would be the first major one since the implementation of the U.S. Constitution. It was caused by a variety of reasons, but there were three major ones. First, the country was ramping down war production, and many men were returning home from active combat. In effect, this amounted to jobs disappearing as more people entered the civilian workforce, creating unemployment. This was also going on abroad as the Napoleonic Wars finally ended, lowering foreign demand for American products, especially war materials. Secondly, without the oversight of a national bank, money had been printed out of control and its value was deflating, and even with the reemergence of a national bank, their efforts proved ineffective. Finally, many people had engaged in public land speculation and had saturated the market, making land less and less valuable. All of these combined into a terrible recession, which was effectively out of the control of the Madison administration, but he still took flak for.

A depiction of a bank run caused by the panic

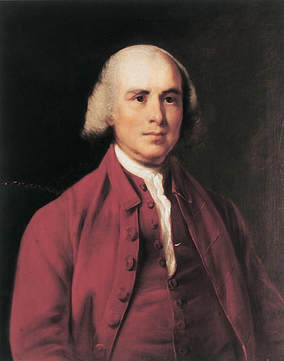

The second thing that came to define the Madison administration was Missouri. In the time of national strife as the panic continued, House Speaker John W. Taylor sought to bring Missouri into the United States as a free state. Normally, this probably would have gone smoothly like all other previous states had been approved. This time, it would prove to be different, however. Perhaps it was caused by the anger started by the panic, or perhaps tension over the issue finally reached the surface, but more and more the free and slave state divide was beginning to affect the nation. Missouri for the most part wished to enter the U.S. with slavery, and northern congressmen were for the most part decidedly against this. This split would create a rupture in the previous strong Liberty Party, and it was over this that the Liberty Party lost considerable ground in southern states like Georgia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas. There even was dissension in Madison's cabinet, with Treasury Secretary Nathaniel Macon and Attorney General Daniel Webster frequently getting into heated arguments about the subject, while Secretaries of State and War James Monroe and Henry Clay respectively tried to keep the peace. During this time, a movement was started to displace current speaker John W. Taylor of the Liberty Party with Democratic-Republican William J. Lowndes, with the Democratic-Republicans hoping enough dissatisfied Liberty Party members would vote their way to enable it to work. The motion would fail narrowly, although it would thoroughly humiliate Taylor.

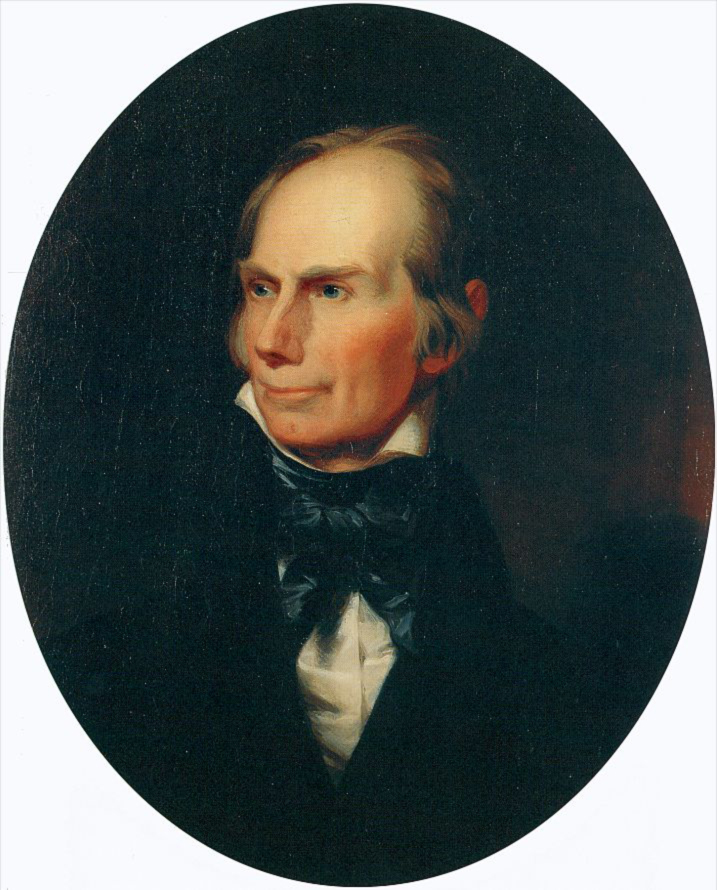

John Taylor and William Lowndes

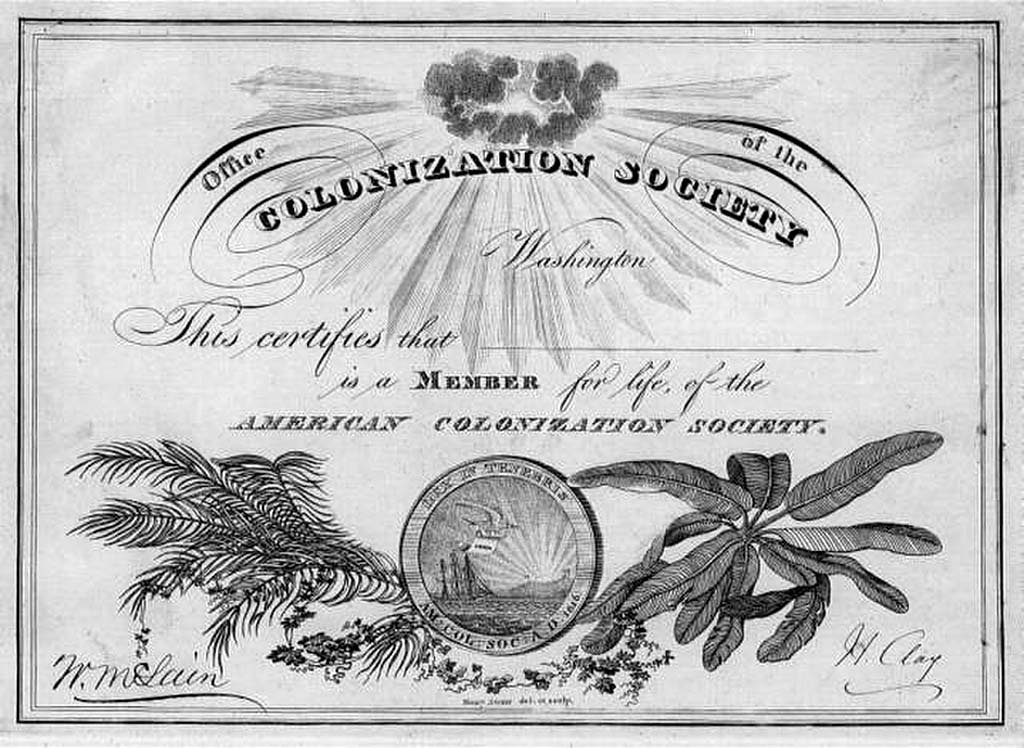

Eventually, the following compromise would be reached. Missouri would be allowed to enter the Union as a slave state, as most of its residents desired. To balance this in the eyes of free staters, however, the Maine territory would be detached from Massachusetts, and made into a free state. This compromise faced two major road bumps along the way, both of which nearly doomed the plan. First, when Vice-President Knox voiced his support for their plan, many Southerners would be quick to point out that Knox owned much land in Maine, and rapidly started a theory that the compromise had been engineered by Knox to increase the value of this land. It was only after a determined campaign against this, including Knox personally stating that he had played no role in crafting the compromise, that this was put to rest. Secondly, Taylor, who still remained a determined anti-slavery man, hoped to include a clause making a dividing line for slavery, with no slavery being allowed north of the Southern Missouri border. This would be fiercely attacked in Congress, and despite receiving the support of several people within the Madison administration, including Clay and Webster, Taylor failed to get it included. Although, to his credit, Taylor ensured that a provision that would have automatically guaranteed slavery in all points south of that line was not included either. This plan would ultimately pass, and a belated president Madison would sign it into law, hoping to settle the issue before he had to face re-election. Thus, the slavery issue was solved for the moment, but neither side was left happy with the result, and both were crafting plans for the future to further their cause.

A map showing the line that Taylor proposed to divide free and slave territory, which would ultimately be rejected

During his presidency, Madison would have to appoint three new judges to the Supreme Court, all occurring in 1820. First, Associate Justice William Ellery would die on February 15, 1820. Madison was in the process of searching for his replacement when Associate Justice Levi Lincoln Sr. would die as well, passing away on April 14, 1820. Having already decided on one new justice, Thomas M. Randolph, a Virginia representative, former candidate for House Speaker, and son-in-law to Thomas Jefferson, Madison was thrown into a panic by Lincoln's death. Hoping to appoint a New Englander to replace Lincoln, who was from Massachusetts, Madison would ultimately decide on Joseph Story, a man whom he had previously only briefly considered. With both of his appointments approved, and the flurry of action over for the moment, Madison would enjoy his respite from nominating justices, only for it to reappear a few months later. Associate Justice Wilson C. Nicholas, a man who had been a friend to both Jefferson and Madison, passed away on October 10, 1820. Saddened by his death, Madison would take longer than usually to nominate a replacement justice. Eventually, he would put Martin Van Buren in as a replacement for Nicholas. As the 1820 election approached, Madison was uncertain of his chances for reelection. Nevertheless, he still held out hope for re-election.

Thomas Randolph, Joseph Story, and Martin Van Buren

Madison and his Cabinet:

President: James Madison

Vice-President: Henry Knox

Secretary of State: James Monroe

Secretary of the Treasury: Nathaniel Macon

Secretary of War: Henry Clay

Attorney General: Daniel Webster

Secretary of the Navy: Smith Thompson