You've piqued my interest! What did you expect them to be? Smaller, larger?I definitely wasn't expecting those borders for the Orange State. Thanks a lot! 🫡

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Popular Will: Reformism, Radicalism, Republicanism & Unionism in Britain 1815-1960

- Thread starter President Conor

- Start date

You've piqued my interest! What did you expect them to be? Smaller, larger?

Both, in a sense. I was either expecting it to cover the Six Counties of OTL' Northern Ireland or just the city of Belfast and surrounding areas. I'm not gonna complain with this half-measure, though.

Yeah, so I wanted to include Antrim and Down, but also areas of Derry as well - so the result is a bit of a coast hugging border. The final decision was informed by the desired borders of Northern Ireland by the Free State ahead of the Border Commission, and a little bit by demographics at the time of partition. Also, coastal areas would be simple to emigrate to by Orangists in the wake of the coup, so I thought there would be a bit of a swell in that direction.Both, in a sense. I was either expecting it to cover the Six Counties of OTL' Northern Ireland or just the city of Belfast and surrounding areas. I'm not gonna complain with this half-measure, though.

Part 5, Chapter XLVI

V, XLVI: Symbolic Restoration

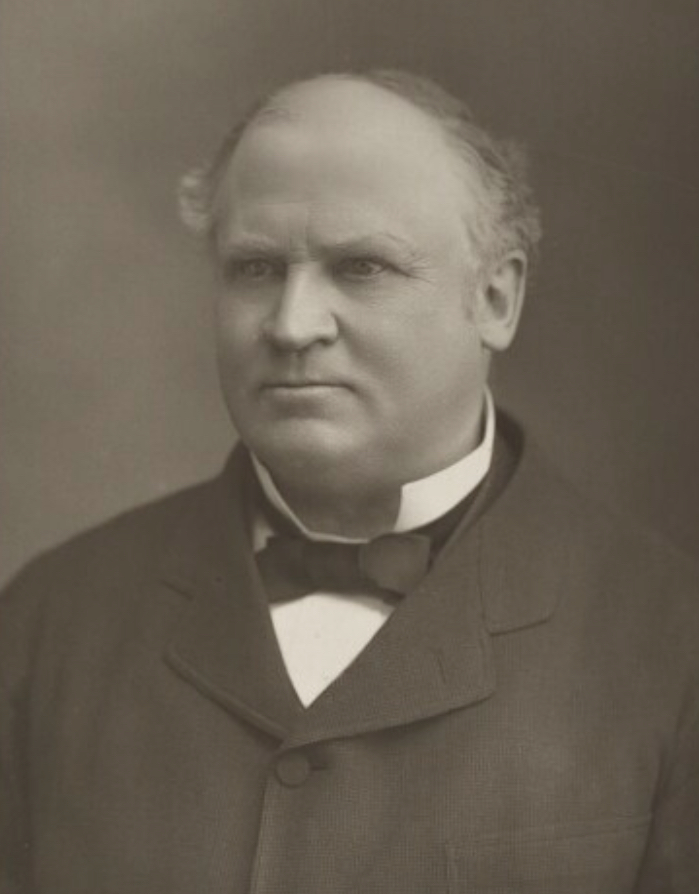

President Regent Edward Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby, 4th President-Regent of the Union of Great Britain

President Regent Edward Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby, 4th President-Regent of the Union of Great Britain

Everyone knew what was coming. President-Regent Stanley had been in serious decline for two years since an illness he suffered in 1891, but by the turn of the year, he looked frail and declined from appearing in public outside of official duties after the agreement with the French. It was an open secret he had been struggling despite his age of just 66.

Aside from his desire to use the role to promote unity wherever possible, Stanley had been a quiet influence on proceedings. Chamberlain believed Stanley was a moderating figure serving the interests of the Unionists, and he had served his purpose. Despite this, over the course of his term, the Unionists had unwittingly rebuilt the aristocracy through the appointed posts under the authority of the President-Regent: Lieutenants, University rectors, and the heads of the various societies and agencies. Most importantly, the Empire, where Stanley had created a web of interconnected aristocratic revivalism. The country elite of England found themselves spread across society once again.

Such restorationism was controversial inside and outside the Unionist Party, but the need for stability and continuity was more important to the party than any dogma about Republicanism. To Republicans, the need to stay out of trouble with the authorities weighed on their minds more than any ideology. Even the SDF, the most radical group in Parliament, forwent any attempt to complain about the President-Regent, owing primarily to Stanley’s popularity with the British public.

In the crisp dawn of April 5th, 1893, the nation awoke to sombre news. The President-Regent, a figure that had been a steady anchor during tumultuous times over the past nine years, had breathed his last. His passing left an unmistakable void, both in the hearts of the British people and in the framework of the Constitution. As the first light of dawn crept over the horizon, the sombre news of President-Regent Stanley's passing began its journey across the nation. In the heart of London, the telegraph office became a hive of activity, operators clattering away at their keys, dispatching messages that carried the weight of a nation in mourning.

In the bustling newsroom of The Union, the air was thick with the scent of ink and paper as journalists scurried about, piecing together the story that would soon be on everyone's lips. The printing presses roared to life, churning out editions that would carry the news from the smog-filled streets of the capital to the furthest corners of the British Isles. The country was reeling from shocking reports of revolution across the channel, and many had looked to Stanley, who had calmed the nation through the March Masscres, for comfort and stability.

In the urban coffeehouses, frequented by the intellectual and the curious, the news arrived with the morning papers. Patrons huddled around shared copies, their voices a low murmur as they read aloud the headlines that spoke of the end of an era. The discussions that followed were a blend of political speculation and personal remembrance, a testament to the late President-Regent's far-reaching influence.

President-Regent Stanley's State Funeral

In the countryside, the news meandered through the rural lanes, delivered by the steady pace of the postman's cart. In the pubs and village squares, locals gathered, their conversations punctuated by solemn nods and the raising of glasses in tribute to a man they had never met yet felt they knew.

Back in the corridors of power, the impact of Stanley's death was no less profound. Chamberlain, upon receiving an urgent telegram, felt the weight of the moment settle upon his shoulders. He summoned his closest advisors, their hurried footsteps echoing through the halls of Whitehall as they convened to discuss the nation's future.

The news also reached Senator Robert Cecil, not through the impersonal words of a telegram but in a carefully penned letter delivered by a trusted courier. As he broke the seal and unfolded the paper, Cecil knew that the contents would not just inform him of Stanley's passing but also of the monumental task that lay ahead. A task that many were already whispering was his destiny to undertake.

Britain found itself at the precipice of a new era, yearning for a leader who could guide them through the murk of uncertainty. The country was anxious, as the newspapers had been filled with stories from France outlining an extremely hostile regime coming to power, refugees spilling into European countries, and financial markets in ruin.

Still, as tradition dictated, the High Chancellor temporarily took over the duties of the Regent, and the Speaker of the House of Commons was quick to action. He called a Grand Committee tasked with selecting the next President-Regent two days after his death. The air in the political chambers was thick with speculation and anticipation.

Whispers and discreet conversations echoed through hallways. Eyes and hopes were turning to a single figure: Senator Robert Cecil. The Senator was not just any statesman. He had recently won the hearts of many an ordinary Briton with his adept handling of international tensions, quelling their fears about an impending war. To many, Cecil seemed like a beacon of hope in a sea of worldwide uncertainty, making him the most likely candidate to fill Stanley’s significant shoes.

Chamberlain and Churchill were less sure of Senator Cecil’s ability to fulfil the role in a conciliatory manner to the Union Government. The Prime Minister wrote to Churchill a few days after President-Regent Stanley’s death, summarizing his apprehension:

“The sombre dawn has cast a shadow upon us all, and our nation is in mourning. The loss of President-Regent Stanley leaves not just a void in our constitutional framework but a deep chasm in the political landscape that we must now navigate.

While his health had been waning, the gravity of his absence truly strikes me now. His moderating hand, even behind the scenes, was felt more than many realise. His actions, often subtle, brought a measure of stability to our tumultuous political realm. I fear we may soon feel the weight of his absence keenly. The annuls of time will remember him as a true father of Unionism.

Eyes and ears are now aflutter with rumours of his replacement, and I must say I am somewhat surprised by the growing consensus around Cecil, though his recent successes cannot be overlooked. I know that you, like me, value the integrity and stability of our nation, so I seek your counsel on this matter. How do you perceive this shift, and what are your thoughts on Cecil potentially taking up the mantle of President-Regent?”

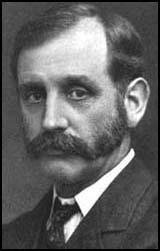

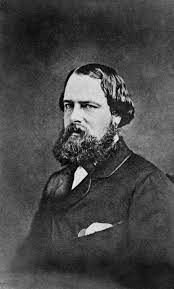

Senator Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, Foreign Secretary, formerly the 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

Randolph Churchill responded the same day, with the letter reaching Chamberlain on the 7th of April, the day before the vote.

“Your letter found me amidst a flurry of whispered conversations. The political corridors are abuzz with speculation, and the mood is electric. I share your sentiments about Stanley’s absence; his quiet yet profound influence was a bedrock on which we stood, often unknowingly.

As for Senator Robert Cecil, I do find the momentum around his name to be rather astonishing. However, it's undeniable that his diplomatic prowess has endeared him to many. But, like you, I do hold reservations. While Cecil has shown himself to be a capable statesman, the office of the President-Regent is not merely about diplomacy. It requires a certain depth, temperance, and wisdom that Stanley so effortlessly exuded. Can Salisbury fill such shoes? I am uncertain.

I propose that we meet, perhaps even with a few trusted colleagues, to discuss the political landscape ahead. This is a crucial juncture for our nation, and I believe that our collective insight can help navigate the challenges that lie before us.”

When Chamberlain and Churchill organised a meeting of the senior leadership to a man, they supported Senator Cecil for the role. Seeing there was no prospect for them to hand-pick the candidate like the previous Grand Committee, they submitted and recommended to the 1884 Committee that Cecil receive the Unionists’ backing.

Republicans were worried about the prospect of Cecil taking the reigns but were unconvinced of the ability of any of their Parliamentarians to gain enough support from Unionists to overturn the will of the 1884 Committee, who issued strict instructions to back Cecil once consensus emerged that he was the most popular candidate. An attempt from Charles Dilke, of all people, to find a challenger failed after just 7 parliamentarians attended his meeting.

As should be expected by now, given the appetite of every President-Regent for the role prior to appointment, Cecil was uninterested in the role. Still, he was convinced to stand when he was told he could continue his diplomatic duties while maintaining the role of Regent. Cecil was nominated first and, with no clear challenger emerging, was appointed without a Grand Committee vote. Britain had a new head of state.

The election of Robert Cecil to the position of President Regent launched a whirlwind, after which Republicans did not know which way they stood. Within a day, Cecil announced that he would not be addressed by the President Regent name, which was his right. Instead, he would restore his previous title, Lord Salisbury, Regent of Great Britain, as his official title. The jettisoning of the Presidential element of his title irked Republicans who had fought hard to prevent his election, and as it turned out, Salisbury was just getting started.

Bust of Salisbury, Originally in Parliament, now in the Museum of the Republic, London

He recognised all peerages, restored titles, and returned land still in the public hands to the church. He also insisted that the prefix of Lord be added to the titles of Lieutenant and Senator, as had previously been the case under Victoria. He used an Order-in-Council to restore the Union Jack, the Monarchist flag, to be flown alongside the Union Flag on all public buildings. Finally, he returned the word ‘Royal’ to hundreds of public institutions and bodies that had been stripped of the title during Unionisation. Most notably, the Royal Navy returned, as did the Royal Society, King’s College, and the Royal Shakespeare Company. Britain returned to a day before the death of Victoria, save the monarch, with one stroke of a pen.

Many wondered why Lord Salisbury didn’t go the whole hog and use his election to recall a monarch to the Crown, but he was significantly craftier than most had assumed. Salisbury wanted to give the Monarchists and Conservatives something they wanted - to return to feeling they were in control through lexicon and nomenclature - without upsetting his party's progressive elements by reversing the Constitutional Laws.

He knew that thanks to the existence of the progressives in the Unionists - former Independent Democrats who supported the Republic until the Constitutional Laws were drafted - there would never be the votes to propose recalling a Monarch, even melded with the current arrangement. Therefore, a policy he called ‘symbolic restoration’ took place. Republicans, buoyed by greater and greater numbers of Parliamentarians, vowed to fight the creeping spectre of Royalism back in Parliament.

This gave the British state the trappings of a constitutional monarchy without the monarch in place. Lord Salisbury’s policies, although entirely superficial, enhanced the idea that the country and aristocratic elite had regained control over Britain for the first time since the death of Victoria. The ‘Regency Era’ is characterised by the chaffing between the emerging and confident Republican movement and the country-based, traditionalist, and Unionist Britain represented by the landed elite, former aristocrats (now civil servants and state officials), and army officers. As Andrew Marr notes in his book, The Making of the Modern Union, Britain 1892-1908:

“In the years that spanned from 1893 to 1903, The Executive in Britain seemed to have taken a firm step back into embracing its counter-revolutionary past. This was not the age of flirtation with radical ideals or the allure of continental enlightenment. Oh no, it was an era where governments sang ballads of 'nationalist Christianity,' where the virtues of heroism, unwavering faith, and cohesive unity were celebrated with fervour.

If there was one event they looked upon with undisguised contempt, it was the Actionist French Revolution, viewing it much like a distasteful wine that one regretted tasting. The totalitarian winds that had blown across Europe in the mid-19th century? Not on these shores.

Instead, Britain's gaze turned to seeing itself as a solid wall standing tall against the tide of modernism. At the helm of this Britain was a closed circle, a club if you will, of aristocrats, dutiful civil servants, and staunch army officers. And reigning supreme amongst them, cloaked in admiration and near reverence, was the figure of Lord Salisbury – the embodiment of the counter-revolution.”

Salisbury’s reforms didn’t end with nomenclature, however. The Regent attempted to simplify the running of the Union of Britain by merging the Regency and Presidency into one apparatus, with a Grand Council that would operate similarly to the Privy Council before the Revolution. While the Union Council would still legally remain, the two bodies would be functionally merged together, and both run from Whitehall, where collaboration would be encouraged.

This had two major effects. Firstly, Salisbury could operate closer to Parliament and force cooperation between the States and Parliament. Secondly, this move would allow Salisbury to have a greater impact on governing, thanks to the influence of the Regency on appointments to the new body. Chief in opposition to this move was Chamberlain, who preferred an independent branch of government for the Union, but he was overruled, as the power in the Executive Authority Act granted to Lord Salisbury permitted him to meet “in the time and place of His Excellency’s choosing.”

To do this, Salisbury appointed just four men to the Union Council: Chamberlain, Churchill, High Chancellor A.V. Dicey, and the newly christened and re-nobled Leader of the Senate, Earl Cadogan. In the first year of his term, Salisbury failed to call a single meeting of the Union Council, preferring the wider cabinet (all members of the Government, each appointed to the Presidency), using the presence of Earl Cadogan and A.V. Dicey as an active quorum to enforce decisions with Union Council assent.

These manoeuvres minimised the influence of Chamberlain on the Government without removing him as Prime Minister, a move which would enrage the party at the local level. They also allowed him to rule more directly, using the full extent of his powers to guide and moderate the decisions of radicals within his own party. He believed such a guiding hand to be pivotal to the fate of Britain to navigate the choppy waters ahead successfully. Smaller cliques of power, a hierarchical system, and the restoration of tradition represented Salisbury’s dream of a government ready for restoration.

Last edited:

Part 5, Chapter XLVII

V, XLVII: Republicanism

George Lansbury, Social Democratic Federation MP for Stockport (1893 - 1940)

George Lansbury, Social Democratic Federation MP for Stockport (1893 - 1940)

The law on unintended consequences is a powerful thing. In this vein, the cosmetic changes from Salisbury were not lost on Republicans, who saw them as restoration by stealth, plain and simple. A broader realisation began to emerge. Without a more significant change to the constitution, every attempt to break the power of the aristocracy would be fruitless. They had the Regency and the Senate, and in many cities and counties, they had Alderman who thwarted attempts at Radical reform. The odds would be stacked against progress, many thought, after symbolic restoration, until levers of power were used to break the monopoly aristocracy had always held on Britain.

After the news of the pronouncements filtered their way through the Union, Republicans were incensed by the blatant power grab. Meanwhile, amidst the grand halls of power, where polished floors reflected the glint of chandeliers, the aristocracy celebrated. After Salisbury's appointment, the rechristened Lord Knutsford spoke of the jubilant atmosphere in the Carlton Club. “The Regent arrived,” he wrote in his diary, “and roused the assembled gentleman in a rendition of God Save the Queen. One figure, I believe it was the Earl of Onslow, ordered a servant to rip the Union flag, that bastardised banner of compromise, from the flag pole and have it brought in, whereupon it was burnt. Joe [Chamberlain] looked gruff and left soon after Salisbury had called for calm among the members.”

Their laughter echoed off the walls, starkly contrasting the sober discussions of the Republicans in shadowed corners of bustling coffee houses. The former, draped in finery reminiscent of a bygone era, spoke of restoring glory and order. At the same time, the latter, a diverse group of determined faces, argued passionately for progress and equality.

Chamberlain was incensed by the manoeuvres. “It is a fool's errand,” he wrote in a letter to his son, Austen, “to claw back the gains made by the Republicans in the last decade. The aggrandising, the pageantry, and the restoration of chivalric honours will do nothing but inflame the Republican side and undo the good work done by Unionists since the creation of the movement. It will aggravate the party at the local level and further the divisions we have sought to avoid. It could bring us to ruin. Have they forgotten the events of last March? Would they wish the horror repeated?”

The Prime Minister was, at this moment, more isolated than ever during his premiership. While he could not publicly disavow the decisions made by the Regent, he was privately gravely concerned by them. He even admitted privately to Randolph Churchill, who refused to reacquaint himself with the ‘Lord’ at the beginning of his title, that the moves to restore the appearance of Monarchy in Britain had convinced him of the need to declare a Republic.

While Churchill disagreed - he remained a staunch advocate of Unionist doctrine - he acknowledged in his diary, “Joe has lost hope for the great Unionist project. While I do not share his pessimism - I believe that passions will calm - if I were formerly a Republican, then a Unionist, I admit I would feel betrayed by the Tories in the party. The election of Cecil was nothing more than a Trojan horse.”

The disenchantment of the Prime Minister against the President-Regent did have some upsides. While around half the party could have been counted as active supporters of the policy of symbolic restoration, the other half, comprising Chamberlain’s core support and the Progressives, unofficially led by Jesse Collings, began to coalesce. Two weeks after the Grand Committee, Collings, Primrose and Chamberlain met face to face. It was said, although no concrete proof has ever been provided, that an invitation was extended to Dilke to join the meeting, although he declined. In secret, the three men began to meet, dine, and discuss the machinations of allowing themselves to allow the Tories back in by the back door. These meetings would foster the beginning of the split that would engulf the Unionist Party in just under two years over the Jameson Affair.

In the industrial heartlands, amidst the soot and clatter of machinery, the working class viewed the aristocratic resurgence with deepening distrust. Calloused from labour, their hands held newspapers that spoke of a world seemingly slipping backwards. In contrast, the emerging middle class engaged in heated debates in their modest parlours adorned with the first fruits of their hard-earned prosperity. Some saw an opportunity for stability in the return to traditional values, while others feared the loss of the hard-won freedoms of a more egalitarian society.

Protests, a nervous pursuit given the violence a year ago, occurred up and down the country, mainly peacefully. Several senior state figures, including Premier of Ireland Michael Davitt, Premier of Scotland Edward McHugh, and most concerningly for the Unionist Party, former Premier of Mercia Jesse Collings, participated in peaceful demonstrations - with the tacit support of Joseph Chamberlain.

The demonstrations drew support from across the political spectrum, including many Progressive Unionists, Liberal Democrats, and members of the (amazingly) still outlawed Social Democratic Federation. Many flew the Red, White, and Green Republican flag, and a minority burned Union Jacks. In the landmark 2008 study of the Republican movement in Great Britain, Peter Wilson described the aftermath of Lord Salisbury’s appointment as “the seminal moment in the creation of a unified, multi-party, multi-ideological Republican movement.”

For instance, the air during a demonstration on April 13th was charged with palpable tension on the streets of Manchester. The clatter of horse-drawn carriages blended with the murmur of agitated conversations. At a meeting in St Peter’s Square, the site of Peterloo, the fervour was almost tangible, with voices rising and falling like a tumultuous sea, each wave of rhetoric colliding with the next. The Chancellor of the Free City of Manchester, Herbert Gladstone, rallied a crowd of nearly 25,000, meandering through the surrounding streets, against Salisbury's actions. “It is not by turning to the past that we will progress this nation but condemn her to slow disintegration,” he exclaimed to the masses.

Herbert Gladstone, Republican and Chancellor of Manchester

Despite the criticism of Salisbury and the decisions of the Unionist Party, it should be noted these demonstrations were policed with remarkable restraint across the country. No arrests were made, and no attempt at coercion was employed. While counter-demonstrations by former Teal Guards and militant Monarchists, now coalescing in the National Unionist movement, were conducted, these too were held in check by a robust police presence, seeking to prevent a repeat of the horrors of March 1892. Holding the superficial united front together, Chamberlain gave a speech in Birmingham, during which he was heckled and booed by the crowd, in which he emphasised the “practical gains of the revolution” and stated the need to “continue to stride confidently into the future.” He was, however, now waiting for an opportunity for the Regent to slip up.

A unique opportunity was afforded to Republicans in the form of a by-election on May 4th in Stockport, triggered by the death of Louis John Jennings, a Unionist Party MP. Local Liberal Democratic Party members, rather than organising a party meeting to select a candidate, issued an appeal to “those of Republican persuasion, of all political creeds, to select a unity candidate to demonstrate this constituency’s distaste at the actions of the Tory attempts to subvert the hard-won freedoms of the Union.” They selected a socialist, George Lansbury, as a ‘United Republican’ candidate for the election and were supported by the LDP, Independent Labour Party, Trade Unions, and a number of local dissenting Unionists.

Despite much ridicule from the Unionists and major press, Lansbury, campaigning for the disestablishment of the Regency and popular election of the Senate, among other pro-Republican policies, won the election. The Sunday Republic ran the victory on its front page with the headline, “Lansbury shocks the Union in a stunning victory for the Republican cause.” The victory demonstrated the popular appeal of Republicanism and secured its revival. While a unified party advocating Republicanism was not on the agenda, the campaign fermented goodwill between differing strands of the movement and concentrated minds in pursuit of the common goal.

Still, some Liberals were unhappy with the cooperation with the outlawed SDF, with Farrer Herschell, a senior anti-Socialist Liberal, writing in The Times before the election, “It is regrettable to see the electors of Stockport given no opportunity between a godless Socialist and a Tory. I truly pity their electoral dilemma.”

Despite the isolated opposition, the Republican movement developed at pace after Salisbury’s symbolic restoration. This desire for cooperation also fostered, perhaps for the first time, a coherent Republicanism policy. One broader realisation by Republicans was that the best way to prevent a takeover of the state by one man would be to not entrust one man to the executive power of the state.

The publication of the second edition of The Constitutional Documents of the First Revolution, 1628–1660, by Samuel Rawson Gardiner in 1893 did much to inform this debate. His preface, written a month after the death of President-Regent Stanley, informed Liberal debate on the issue. Gardiner presented two hypotheses in the book. The first - that Charles wanted to conserve and protect the past and caused friction between Parliament and the Crown - rang true and spoke to Republicans who believed Lord Salisbury was a reactionary blockade to the natural progress towards the Republic. The second - that the revolutionaries benefitted from collective leadership, and the Commonwealth only collapsed once power was centralised under Cromwell (a claim historians now dispute) - left a great impression on the movement.

Samuel Rawson Gardiner, Author of The Constitutional Documents of the First Revolution, 1628–1660

Especially among the SDF, Salisbury’s rejection of the apparatus of Republican rule fostered a feeling that we wouldn’t always find the right man to act as custodian of the order, like Charles and Salisbury, but a small group could wield the same influence with less room for centralisation. As SDF organiser George Bernard Shaw noted in a letter to Annie Besant’s The Sunday Republic on May 11th, “The weakness of delivering temporary royalty is that sometimes, the head is not large enough to carry the crown. We, in our organisation, believe that the weight should be carried collectively.”

Following the revival of Republicanism the previous year, Republicans began to discuss openly the drawbacks of the 1875 Constitutional Laws and proposed improvements in publications like The Sunday Republic. One stood out in its clarity and conviction among the voices of dissent. Published in 'The Sunday Republic,' a letter penned by the revered MP from Wales, David Lloyd-George, in support of Lansbury, captured the nation's attention.

“We stand today at a most pivotal juncture in the chronicles of our great nation, a nation that has withstood the tempests of time and emerged resplendent. Yet, we find ourselves amidst a swirling maelstrom of political machinations that threaten to steer us away from the glorious path of progress and enlightenment back into the shadows of an archaic and feudal past.

It has become distressingly apparent that the recent reforms proposed by Lord Salisbury are not but a thinly veiled attempt to drag this proud nation back to the dark days of aristocratic dominance and elitism. These reforms, I fear, are a siren song, alluring in their melody of tradition and heritage yet perilous in their intent.

Under the guise of preserving our cherished traditions, what we witness is a subversion of the very essence of our 1875 Constitutional Laws. This, I must assert, is an affront to the spirit of republicanism – a spirit that breathes life into the ethos of our constitution. We are, I submit, duty-bound to raise our voices against such regression.

I urge us to ponder deeply on the proposition of concentrating vast executive powers in the hands of a single Regent. This is a dangerous vestige of an age best left behind. The unchecked authority wielded by Lord Salisbury, under the cloak of regal prerogative, stands testament to the inherent vulnerabilities of such a system. The gravitation back towards hierarchical governance and the consolidation of power within select aristocratic circles is a stark reminder of a feudalistic past we have striven to transcend.

Might we embrace the dream of a true republic? If so, we must question the necessity of entrusting such immense power to one individual. Would it not be more prudent, more reflective of our democratic ideals, to have a council – diverse in thought, representing the myriad voices of our great nation? Such a council would serve as a bulwark against the whims of any one person, ensuring that the path we tread is one of balance, fairness, and representative of the collective will.

Moreover, our current Constitutional Laws, while groundbreaking at their inception, lack the robust fortifications necessary to safeguard against the erosion of our democratic values. It is incumbent upon us to establish clearer demarcations of executive powers, institute mechanisms for greater accountability, and perhaps even consider term limits to prevent the ossification of power within a select few hands.

The recent manipulation of the Union Council by Lord Salisbury and the subsequent curtailment of its intended role is indicative of loopholes that must be addressed posthaste. It is a grotesque perversion of democratic principles for a Regent to diminish the influence of duly elected representatives.

Furthermore, the composition of our Senate and its susceptibility to the machinations of influential cliques pose a significant impediment to the enactment of meaningful reform. This situation demands our immediate attention and warrants a thorough reassessment and possible reconstitution.

In conclusion, let all Republican-minded Patriots heed this clarion call to action. We must evolve our constitution, fortify it against the ambitions of the few, and ensure it remains a bastion of the people’s will. Let us not allow the hard-fought progress towards republicanism to be relegated to mere footnotes in our history. For if we fail to act, we risk being ensnared once again in the fetters of a bygone era.”

David Lloyd George MP, Prominent Republican

Symbolic restoration, while nostalgic for some, served as a unifying moment for many others, hitherto contented with the Constitutional Laws. The spectre of one man's overarching influence raised grave concerns among Republicans and reformists alike. The very essence of their democratic ideals seemed under threat. With the aristocracy subtly reasserting their influence and traditional structures being revived, there was a palpable unease among the public about the trajectory of their nation.

It was in this atmosphere that voices of dissent and reform grew louder. Publications like The Sunday Republic served as platforms for debates on the very fabric of the nation's governance. Among them, David Lloyd-George's compelling argument for a collective council resonated deeply. His vision of decentralising executive power, ensuring shared responsibility, and mitigating the risk of unilateral decisions underscored a shift in the public discourse. Finally, in June, Republicans across the country formed The Spence Society, named after early Republican Thomas Spence. This organisation, still functioning today, is one of the key foundations of the Republican movement.

The Regency Era thus marked a pivotal era in British political history, teetering between traditions of the past and visions for the future. The tension between monarchic nostalgia and the clamour for a more democratised governance would continue to shape the political landscape, with the legacy of Lord Salisbury's 'Regency Era' casting a long shadow on the years to come. Tellingly, Salisbury’s Regency wouldn’t end with the abolition of the institution itself but would set the wheels in motion for the ultimate victory of the Republicans in 1908.

India (containing OTL Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Burma) is run as a mixture of Category 2 & 3 territories - so it is run with an appointed British Administration with a mixed Civil Service. Currently it doesn’t have responsible government, but the development of the political system, including the rise to prominence of the SDF and LDP will have an impact on Indian policy, including the Princely States. I’m sorry I haven’t gone into it further just yet, but the political stars haven’t aligned yet for it to be a prominent issue in British politics just yet. That will change very soon, and India will be covered again in an update soon. Unionisation is returning to the forefront 👍🏻Any changes in India from Otl?

Was'nt a responsible government given in 1880 itl?

What would happen to Princely states after 1908?

Part 5, Chapter XLVIII

V, XLVIII: National Democracy in Action

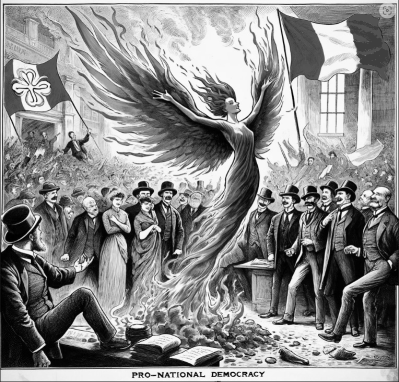

Pro-National Democracy Cartoon, featuring crowds with the Shamrock Banner, a common NDP flag, and the Green-White-Green Tricolour, another common NDP flag

Pro-National Democracy Cartoon, featuring crowds with the Shamrock Banner, a common NDP flag, and the Green-White-Green Tricolour, another common NDP flag

Amongst the furour of symbolic restoration, Ireland was one area striving confidently into the new area, free from interference. The nation from 1892 under the Premiership of Michael Davitt stands as a pivotal era marked by transformative economic and social policies alongside a growing wave of united Irish nationalism. Appointed as Premier of Ireland and leading the National Democratic Party (NDP), Davitt's administration was driven by a strong ideological commitment to Georgism, which shaped its approach to land reform, taxation, and the broader economic landscape of Ireland. Upon the return of the NDP to Government in 1892, Davitt and his Ministers works incredibly fast, with significant reforms passed in the first 18 months of the term.

Davitt's economic policies furthered the defining goal of National Democracy: addressing the disparities created by the unequal ownership of land. Central to this was the continued implementation of the Land Value Tax as part of the Plunkett-Sexton Plan. This plan introduced a tax on the unimproved value of land, shifting the economic burden from labour and capital to landowners. The tax ranged from 2d in the pound for smaller estates to 6d in the pound for larger estates, with the wealthiest landlords paying up to 8d in the pound. Such a progressive taxation system aimed to alleviate the burden on tenant farmers and the working class, who had long been subject to the whims of absentee landlords. It also wished to diversify and spread land ownership, by pressuring large landed estates through taxation into selling small plots to put economic power in collective Irish hands.

The Plunkett-Sexton Plan also involved the transfer of former Crown Lands to tenant farmers and the establishment of a 'Congested Land Board' to regulate fair rents and manage absentee lands. This initiative significantly redistributed land ownership and aligned with Davitt's vision of "Free Land, Free Trade, Free People." The plan notably included exemptions for land used for religious purposes, government buildings, common land, and, crucially, for land pooled into cooperatives. These cooperatives were integral to Davitt's vision of empowering Irish farmers. They provided a framework for collective ownership and management of agricultural land, promoting self-sufficiency and resilience among the rural populace. This was a radical departure from the traditional landlord-tenant system and was seen as a step towards a more equitable and sustainable agricultural sector.

The Davitt government introduced the Cooperative Farming Act of 1892 on July 22, 1892. This act passed with a strong majority of 75 votes in favour and 41 against in the Legislative Assembly and passed with a majority of six in the Legislative Council three weeks later. The legislation was crucial in promoting the cooperative movement in Irish agriculture. It provided legal and financial frameworks for establishing farming cooperatives, thus empowering tenant farmers to own and manage agricultural land collectively. The implementation of these reforms had profound economic effects. The redistribution of land ownership through the Land Value Tax and cooperative movement led to a more equitable distribution of wealth. Absentee landlords, burdened by the new tax regime, sold their lands, which were then redistributed to Irish tenant farmers.

Managed by Horace Plunkett, a key NDP loyalist who was made Minister of Agriculture in Davitt’s Government, the implementation of the cooperative elements of the Plunkett-Sexton Plan meant that by 1892, 54% of the land in Ireland was managed in cooperatives: mostly as planned agricultural communities with small plots, voluntarily collectively bargaining with importers on the mainland and for export abroad. Ireland produced surpluses that allowed the cooperatives to invest in new machinery, and amazingly, by 1892, Ireland produced more goods for export than any other state in the Union.

Moreover, Davitt's government took significant steps to revitalize the Irish language, recognizing its role as a unifying cultural and nationalistic force. A report in 1891, the catalyst for the legislation, had drawn stark warnings for the Irish nation. In 1881, analysis showed that of those born in the first decade of the century, 45% of the population had been raised with Irish, and in 1891, just 10% were raised in the national language. The findings summoned a sense of deep questioning of the nature of Irish statehood, particularly among National Democrats. While O’Connell’s Catholic Liberalism of the Repeal Movement was lukewarm to the status of the language, believing it was an inhibitor to progress, to the new generation of politicians emerging through the NDP, the Irish language was a key element of state-building. The Unionists also preempted the crisis with the Union State Language Act of 1892, introduced within two weeks of the beginning of the new Parliamentary term, which indicated that English should be the sole language for administration. This was a direct attack on linguistic minorities: the Welsh, Irish, and Scots Gaelic, and (however limited) Cornish.

The Gaelic League, founded in 1893, played a crucial role in this effort, organizing classes, immersion experiences in Gaeltacht areas, and publishing materials in Irish. The revival of the language was intertwined with the broader political project of unifying Ireland under the banner of a shared heritage and identity. Davitt announced at the NDP Congress in 1893 that the party’s name would change from the National Democratic Party to its Irish language translation, An Páirti Daonlathaithe Náisiúnta na hÉireann. Davitt himself would sign letters from this date as Mícheál Dáibhéad, the translation of his name in Irish.

The Irish government took a decisive step towards cultural resurgence with the landmark Irish Language Act, or Acht na Gaeilge, of 1893. Passed on June 5, 1893, the Act was a bold affirmation of the Irish language as the national language of Ireland. One of the Act's key provisions was the significant increase in funding allocated to the Gaeltacht areas - regions where Irish remained the predominant language. This infusion of resources was aimed at bolstering educational facilities, supporting local economies, and promoting cultural activities that fostered the use and preservation of the Irish language. The Act recognized the Gaeltacht regions as vital bastions of Irish culture and language, deserving of special attention and support to ensure their vitality and growth.

Perhaps the most transformative aspect of the Act was the introduction of language requirements for civil service, education, and other government positions. Under this new mandate, proficiency in the Irish language became a prerequisite for employment in various government roles. This policy was not merely about filling positions with Irish-speaking individuals; it was a strategic move to ensure that the language regained its stature and became a living, breathing part of the nation's administrative and educational systems.

The Act also paved the way for the Irish language to be taught as a compulsory subject in schools across Ireland, not just in the Gaeltacht regions. This educational policy aimed to foster a new generation of Irish speakers, ensuring that the language was not relegated to the past but was a dynamic and integral part of Ireland's future. In the realm of public service, the Act mandated that all official government communications and documentation be available in both Irish and English. This bilingual approach was a significant step towards normalizing the use of Irish in everyday governance and public life. Davitt also encouraged the use of Irish on the mainland, also, encouraging Irish workers in the Northern States, like Yorkshire and Scotland, to keep up the language. One of his initiatives was becoming a club patron of Celtic Football Club in 1891. The club invited Davitt to the ground-breaking ceremony of Celtic Park, a football club for the Irish Community in Glasgow.

In Yorkshire, he is remembered as one of the founding fathers of the movement that eventually gave the State the Tykegaelg creole of Irish - a unique mix of the Irish Language and Yorkshire dialect, spoken by 150,000 residents in Yorkshire and Lancashire. Télefis Foer, the Tykegalg-language television station based in Leeds, is based at Teak na tDabhet in his honor.

Davitt breaks ground at Celtic Park, 1892.

Elsewhere, the movement to revive Gaelic encouraged further movements across the Celtic states. Cornwall created a commission for revitalising Kernow the next year, the new Welsh Government enacted similar legislation in 1895, and the Scottish Government, under fellow National Democrat Edward McHugh, unveiled reforms designed to promote the use of native languages in the Highlands. McHugh also established Comhairle nan Eilean Siar (Council of the Western Isles), which was predominantly Gaelic speaking, to safeguard the language on the Islands and protect its unique interests. With 20 years of the "Celtic Revival," as it became known in the Union, the number of monolingual speakers would increase by 15% in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, and the number of bilingual speakers would increase by 40%.

In Cornwall, Henry Jenner founded the Pentreath Society, a group named after the presumed last native speaker of the language, and led a successful campaign to research and map out the language with the help of the Charter Fragment from the British Museum - a fragment of Middle Cornish text. With funds from the Gaelic League, comprehensive classes were taught as early as 1896. The Cornish Language Act of 1906, passed during the Republican Revolution along with the reforms to rename the Cornish Legislature as the Stannary Parliament, increased its usage in national bodies, furthered literature and culture, and was regarded as the beginning of the long revival, which culminated in Cornwall declaring itself officially bilingual in 1999. Similar efforts, while not as wide-reaching given the multi-national composition of the island, were conducted in Ellan Vannin, which changed its name from the English translation, Isle of Man, upon gaining statehood in 1903. Today, the revival of the Manx Language is considered complete, and around 17% of the population, or around 800,000 people, claim to speak some of the language mostly; Manx speakers are confined to those who attend the sixteen Bunscoillí Ghaelgagh, and any of the eight Manx-medium secondary schools.

On the economic side, the establishment of the Irish National Bank (INB) during Davitt's Premiership was a landmark event in the economic history of Ireland. It was a visionary move aimed at transforming the financial landscape of rural Ireland, which was predominantly agrarian and heavily dependent on agriculture. On October 9, 1892, the Irish National Bank Establishment Act was passed by a vote of 78 to 38 in the Legislative Assembly. This act laid the foundation for the Irish National Bank, providing an initial endowment and outlining its role in offering accessible credit to the agricultural sector. This act faced significant opposition from banking interests but ultimately succeeded due to its promise of economic independence and growth.

The primary objective of the Bank was to offer accessible and affordable credit to farmers, thereby promoting agriculture, commerce, and industry within Ireland. The initial endowment of £300,000 to set the bank up. This money was raised by a bond issue and an endowment from the sale of lands managed by the Congested Districts Board. This funding was intended to be used to provide low-interest loans to farmers for crop cultivation, livestock breeding, and the purchase of farm equipment.

The Irish economy was primarily based on farming, with a significant portion of the population engaged in agriculture, especially in the cultivation of potatoes and grains. The farmers of Ireland faced numerous challenges, including fluctuating market prices, exploitation by intermediaries, and exorbitant interest rates charged by urban-based banks. Davitt, understanding the plight of the Irish farmers and their vulnerability to the volatile market and predatory lending practices, proposed the establishment of the INB. This institution was designed as a credit union-style entity aimed to liberate Irish farmers from the grip of high-interest loans from banks located in major cities on the mainland.

The proposal, however, faced significant opposition from various quarters. The banking trusts, which had a stronghold over the country's financial affairs, saw the Bank as a direct threat to their interests. They feared that the establishment of a state-backed financial institution offering low-interest loans would diminish their market share and influence. Similarly, the grain and railroad trusts, which had long profited from the struggles of the rural populace, opposed the Bank, fearing it would empower farmers and reduce their dependence on these trusts.

In response to Davitt's proposal, these entities undertook a series of actions to thwart the establishment of the Bank. They funded political opposition, engaged in legal battles to challenge the Credit Union's formation, and boycotted the sale of its bonds. The Catholic Church, through the General League, also ramped up its opposition to the plan.

Despite these obstacles, the determination of Davitt and the NDP, along with widespread public support, eventually led to the successful establishment of the Irish National Bank. The Bank quickly became a lifeline for Irish farmers, offering them a viable alternative to the exploitative lending practices they had endured for years. It provided much-needed financial support, enabling farmers to invest in their land and livestock, thereby improving their yields and livelihoods.

Recognizing the importance of robust infrastructure in industrial development, Davitt's government continued to invest heavily in improving transportation networks, including railways, roads, and ports. A public work scheme, paid for by a mix of national and municipal bonds, known as “Patriot Bonds,” help foster a sense of economic pride in the country, and many of the projects, like the Dublin to Dundalk Canal, the Cork to Galway Railway, and the Drogheda Shipping Port, are still in use today. This facilitated easier movement of goods and resources, reducing costs and improving efficiency for industrial operations.

Drogheda Shipping Port, 1892

Davitt's government established research and development grants for industries, particularly in sectors like textiles, shipbuilding, and food processing. Partnerships with universities and technical institutes were encouraged to facilitate knowledge transfer and to develop a skilled workforce tailored to the needs of the evolving industrial landscape.

The economic policies of the Davitt government, particularly its implementation of Georgist principles, faced criticism and resistance from various quarters. The LVT, while redistributing wealth and breaking up large estates, also sparked concerns among the landowning class and those wary of too drastic an economic transformation. However, the popularity of these policies among the tenant farmers and the working class provided a solid base of support for the NDP.

In addition to these economic reforms, the Davitt government also focused on social welfare. The Irish Public Health and Welfare Act, passed on January 12, 1893, with an overwhelming majority of 89 to 27, was a landmark piece of legislation. It mandated improvements in sanitation and clean water supply and introduced rudimentary healthcare services, particularly in rural areas. It also laid the groundwork for the construction of hospitals and the development of a district nursing system.

The period also saw the expansion of public services, including developing a rudimentary district nursing system and constructing hospitals for working-class mothers, signaling a commitment to public health and the well-being of the most vulnerable. Improvements to the Department of Public Health were notable, focusing on sanitation, clean water, and sewage disposal.

In education, Davitt's government expanded technical education and built new schools, reducing class sizes and making education more accessible. The introduction of free textbooks and assistance with transport costs further democratized education, reflecting the government's belief in the transformative power of learning. The Irish Education Reform Act of 1893, passed on February 18, 1893 brought sweeping changes. It expanded technical education, reduced class sizes, and introduced free textbooks, marking a significant step in making education accessible to all Irish children.

Despite these successes, the Davitt government faced formidable challenges. The opposition, comprising various factions including traditionalist elements and those aligned with the Orange Movement, continually challenged the NDP's policies. The issue of reunification with the Orange State remained contentious, with debates often centered around questions of identity, sovereignty, and economic interests. Much of this debate concerned the status of Catholics in the Orange State. While the Irish economy was improving, much of the midlands of the country were still overwhelmingly poor, and with agricultural production becoming more efficient, more young men and women were attempting to make it in cities. For much of the North of the Island, Belfast retained significant pull as a metropolis with jobs and better standards of living.

Thousands poured in to both sides of the city, but Catholics were routinely forced into a position of so-called “ghetto labour.” This practice saw workers from outside the O.S. employed by Belfast factories, but forced to live in West Belfast, which remained in the State of Ireland after the declaration of Orange Statehood. The population of Belfast’s Western Suburbs swelled, and poor wages and conditions exacerbated poor living conditions. The Orange State Government, under the Unionist Party of the Orange State (UPOS), aided by groups like the Orange Order, Legitimist Church, and National Unionists, wished to protect the status of its citizens, fight attempts to force down wages for Loyalist and Protestant workers, and discourage Catholics from settling in the City, so used influence over housing to keep the unsatisfactory arrangement going and Catholic workers locked “over the wall,” as West Belfast was known,

The presence of Orange groups in suburbs around West Belfast further complicated the situation. Living in the State of Ireland but working in the Orange State, these communities were fiercely pro-Unionist, and regarded the Catholics of West Belfast to have stolen their citadel for themselves. The Orange Order lodge in West Belfast was heavily linked to pro-terror groups, and some of the worst fighting in the March Massacres in Ireland took place in the city. Similarly, in West Derry, militant Legitimists purposefully moved to the area to attempt to seize it for the Orange State. While Sir Thomas Russell, Premier of the Orange State, and Davitt had cordial relations, junior government members on both sides were engaged in a campaign to arm and protect their communities from the other side. A catalyst, it was thought, would explode the situation.

The Irish Language Act proved just the catalyst. Upon its passing, the City of West Belfast Council decided to honorarily change its name to the Irish Comhairle Cathrach Bhéal Feirste Thiar on July 1, 1893. Legitimists reacted strongly against the move, targeting the ramshackle council chambers with bricks and attempting to storm the building. More from Belfast City came “over the wall,” and a riot ensued. When Irish Minister for Internal Affairs, Thomas Brennan, attempted to contact his opposite number in the Orange State, Edward James Saunderson, about the affair, he was stonewalled. It was later revealed this was because Saunderson had attended one of the protests. Irish State Police were left to protect the building alone, 3 were killed, and 1 injured in the fighting.

Davitt went to the Irish Legislature and provided a stunning rebuke of the Orange State:

"The recent events in West Belfast are not just a stain upon the fabric of our society; they are a glaring testament to the abject failure of the State in Belfast to uphold the principles of justice, equality, and human dignity. The heinous actions of these groups, the insidious practices of some within the community, and the deliberate segregation and mistreatment of our Catholic brethren in West Belfast are a flagrant violation of every tenet of civil society.

The State to the North has not only turned a blind eye to these atrocities but has, in fact, been complicit in perpetuating this cycle of violence and discrimination. Their actions are a deliberate attempt to marginalize and disenfranchise a significant section of our populace. The brazen attack on the City of West Belfast Council is a blatant assault on the democratic rights of our citizens.

Let it be known that we, the people of Ireland, will not stand idly by as our fellow citizens are subjected to such barbarism and injustice. We demand that the State to the North take immediate and decisive action to quell the violence, to disband these militant groups, and to ensure the safety and rights of all its residents and those within its employment. Let us raise our voices against tyranny and oppression. Let us strive for a future where tolerance, understanding, and mutual respect are the cornerstones of our society."

In summary, Michael Davitt's tenure as Premier of Ireland marked a significant period of economic, social, and cultural transformation. His administration, underpinned by Georgist principles, successfully implemented sweeping land reforms and introduced innovative financial mechanisms like the Irish National Bank, profoundly impacting Ireland's agrarian economy. The Cooperative Farming Act and the Land Value Tax reshaped Ireland's agricultural landscape, empowering tenant farmers and challenging the traditional landlord system.

Additionally, Davitt's commitment to cultural revival, particularly through the Irish Language Act, not only preserved the Irish language but also instilled a strong sense of national identity and unity. His efforts in improving public health, education, and infrastructure further demonstrated a comprehensive approach to nation-building. However, Davitt's reforms and policies were not without challenges, facing opposition from various quarters and stirring tensions in the North, notably in West Belfast. These challenges underscore the complex interplay of politics, economics, and culture in Ireland's journey towards self-determination and national identity during this pivotal era.

Last edited:

Part 5, Chapter XLIX

V, XLIX: Not A Fit of Absence of Mind

Sir Robert Herbert, Colonial Secretary

While colonial matters had been central to the ideological glue that held the Unionist Party together, in reality, the first full term of its government had neglected it somewhat. While Australasia had gained Union status in 1891, other colonies were left largely untouched. This chapter examines two cases of significant imperial weight for Britain - India and Greater Southern Africa.Sir Robert Herbert, Colonial Secretary

Part 1 - Killing Nationalism with Kindness

A key part of the early Unionist reforms, changes to India’s governance, including the creation of the High Commission, which acted as a coordinating government across the newly created Union of India, was regarded as a success in Britain, with the railways, in particular, providing a feather in the cap for the Unionist Government’s ‘civilising mission’ on the subcontinent.Others, including prominent figures in British politics, disagreed. Dadabhai Naoroji, often referred to as the Grand Old Man of India was such a figure. Naoroji’s work and dedication to the economic plight of India under British rule established him as an intellectual force in this period that could not be easily dismissed. Naoroji's meticulous approach in delineating the economic drain from India laid a substantial foundation for the argument for Indian self-governance.

Dadabhai Naoroji MP, Liberal Democratic Party (1893-1908)

Naoroji's early work in economics was marked by an unyielding commitment to unveil the true extent of Britain's exploitation of India's wealth. His Drain Theory, which detailed the systematic transfer of wealth from India to Britain, was groundbreaking when he first presented it to the Oxford Union in 1891. By demonstrating how India's wealth funded British infrastructure both within and outside of India, Naoroji presented a compelling case for the economic emancipation of his homeland. He astutely highlighted the imbalance in trade relations and the suppression of Indian industry in favour of British economic interests.

This shared struggle against imperial economic practices formed a bridge between Naoroji and Michael Davitt of Ireland. Davitt, a staunch advocate of land reform in Ireland and a member of the National Democratic Party (NDP) saw in Naoroji's advocacy a parallel to the successful Irish quest for self-determination and control over their resources. The National Democracy movement, which Davitt championed, was inspired by Georgist principles and sought to end economic exploitation by absentee landlords, much like Naoroji’s battle against imperial extraction.

The synergy between the Indian home rule movement and the Irish National Democracy was not coincidental. Both movements sought to reclaim control over local resources and governance. Naoroji and Davitt shared a mutual admiration for each other's work; both saw the importance of a self-sustaining economy as the backbone of national freedom. Their correspondence and shared platforms at various international gatherings helped to foster a spirit of solidarity between Indian and Irish nationalists.

Naoroji's election to the British Parliament in August 1893 as a Liberal Democrat Party (LDP) MP for Finsbury was a watershed moment for the Indian home rule movement. It was a victory not only for Naoroji himself but also for the broader struggle against colonialism. His narrow win by a margin of eight votes was emblematic of the fierce contest between imperial hegemony and the rising tide of nationalist sentiment - the Unionist candidate, Frederick Thomas Penton, had been stationed in India and spoke prominently about the desire for Imperial unity that Naoroji’s election would threaten. In Parliament, Naoroji's voice became an instrument for the Indian cause, and his first speech solidified his stance that India's relationship with Britain needed to be redefined – from that of a subject people to equal partners within the Empire.

Naoroji's advocacy for Indian home rule was buttressed by his position as an MP, which allowed him to bring the struggles of India into the political mainstream of Britain. His insistence on equal opportunities for Indian professionals and his calls for Britain to invest in Indian industries mirrored the NDP's aspirations for Ireland. The shared ideologies and strategies between Naoroji and the Irish National Democracy movement highlighted the interconnectedness of the global struggle against colonial exploitation and for national self-determination.

In the months leading up to his election, Naoroji worked tirelessly, not only to raise awareness about the plight of India but also to build alliances with other colonized nations, including Ireland. His engagement with the NDP and figures like Davitt marked a growing awareness of the global nature of the fight against imperialism. This period of Naoroji's life, culminating in his election as an MP, was marked by the convergence of his economic theories with political action, setting a precedent for future generations of Indian nationalists and creating a blueprint for collaborative resistance that transcended national boundaries.

Joseph Chamberlain in 1893

Chamberlain had some sympathy with the Indian home-rule movement and the INC, as he had with Davitt’s National Democracy, but believed that India could and should be controlled and managed in a different way to the white colonies. While Unionism had an international flavour, it was highly centred on the idea of Britain expanding its influence and highly connected to the Imperial concept.

Chamberlain had noted in the Highbury Hall conference his desire to further the process of Unionisation, whereby colonies would be slowly prepared to be integrated into a union of entities with similar governance structures - mainly parliamentary democracy and federalism. India was considered a mix of so-called category two and three statuses, which considered territories “incapable” of running themselves. According to Chamberlain’s schedule, India would expect to receive self-government way down the line.

Naoroji's election, along with important work by senior SDF figures, like The Sunday Republic’s editor-in-chief Annie Besant, brought Indian home rule to the forefront and demanded a rethink of Unionist colonial policy. To Chamberlain, his ongoing political alienation from the core of the Unionist Party, now increasingly guided by Lord Salisbury, India, and the colonies, presented a method of regaining some control.

Annie Besant, Editor of The Sunday Republic

Salisbury was little interested in the minutiae of colonial management but rather in grandiose objectives of prestige and power. His disinterest would allow Chamberlain to further his ideological plans, informed by Seeley and the Imperial Federation League. India and the other colonies not involved in Unionisation efforts could present a first step to regaining an ideological steer for the party.

In the wake of heightened calls for Indian home rule, Prime Minister Joseph Chamberlain and Colonial Secretary Sir Robert Herbert unveiled a legislative program aimed at pacifying the Indian nationalist aspirations by addressing the systemic issues plaguing India under British rule. This program, while not granting full autonomy, sought to alleviate the critical points of contention by instituting a set of reforms to redress certain issues.

The central piece of legislation was the Indian Council Act of 1894. This act aimed at redressing the imbalance of power and intiating the process of transitioning India closer to self-governance within the Union framework. The Act established an appointed Central Legislative Council, including a number of native members, introducing a higher degree of representation and a move towards more inclusive governance. The council was to consist of twelve ex-officio members, including the Governor-General and High Commissioner and other members of the High Commission. It also included eighteen additional members, with a balanced mix of official and non-official Indian members, ensuring a platform for Indian voices.

The timeline for the passage of these bills was swift and decisive, demonstrating the Unionist Party's commitment to stemming the tide of nationalism through proactive reforms. The Indian Council Act of 1894 was introduced in Parliament in early December and, after vigorous debates and some resistance, was passed by April 1894.

Subsequent legislation aimed to address the lack of internal investment and the absence of immigrants bringing capital and labour for economic growth. Passed in January 1894, this act authorized the allocation of funds for the construction of railways, canals, and roads and established incentives for industries that employed a predominantly Indian workforce. To counter the drain of wealth from India, the Indian Financial Reforms Act of 1894 was introduced, requiring that a portion of the minimum amount of revenue generated from India's resources and industries be reinvested within the country. This act, passed in May 1894, aimed to curtail the outflow of capital and ensure that the principal income earners in India reinvested their wealth domestically.

Chamberlain, speaking in the Commons, boldly stated, "We seek not to rule over India, but to empower her people to rule alongside us. The legislation we have passed is a testament to our belief in India's potential and our commitment to the Empire's overall prosperity." Colonial Secretary Sir Robert Herbert described the actions collectively as “Killing Nationalism with Kindness.”

However, opposition to these policies was significant. Critics argued that the reforms were superficial and failed to address the core issue of Indian autonomy. Nationalist leaders, including Davitt, Besant, and Naoroji, while acknowledging the reforms as a step in the right direction, continued to advocate for complete self-governance. The opposition of senior state leaders, like Thomas Farrer and Edward McHugh, and young parliamentarians like Herbert Asquith, who spoke with increasing confidence about the Empire, helped develop a sense of pro-imperial reform within the Liberal Democratic Party.

The Unionist Party's legislative program, while extensive and impactful, was thus the beginning, not the end, of India's journey towards self-rule. It represented a shift in British policy, from overt control to a more subtle and calculated approach, aiming to quell the rising tide of nationalism not with brute force but with the promise of progressive reform and the gradual inclusion of Indian participation in the governance of their own land.

Part 2 - Greater Southern Africa

Elsewhere, the late 19th century was a period of profound transformation in Southern Africa, marked by political manoeuvres and aspirations for greater unification under British influence. The region, consisting of the Cape Colony, Natal, the Orange Free State, and the Transvaal, while politically disparate, was bound by intricate socio-economic ties. The discovery of diamonds and gold had particularly altered the region's economic landscape, with the Transvaal, bolstered by the Witwatersrand Gold Rush, emerging as a potential powerhouse. The influx of Uitlanders, primarily British, into the gold-rich territory, introduced new complexities into the already intricate political dynamic, setting the stage for conflict and the eventual push for consolidation under British dominion.At the forefront of this push for unification was Cecil Rhodes, Prime Minister of the Cape Colony and Governor under the auspices of the British South Africa Company. Rhodes, a man of expansive ambitions, envisaged a Southern Africa unified under British control—a vision that extended beyond mere economic dominance to encompass a political federation that would consolidate British influence from the Cape to Cairo.

Cecil Rhodes, Prime Minister of the Cape Colony

Rhodes's strategy was underpinned by the principles of Unionism, an ideology that sought to amalgamate disparate territories into a federated structure, mirroring the successes of the Union of Australasia. His proposal, presented to Lord Salisbury and Joseph Chamberlain in September 1893, delineated the territories of the Cape and Natal as Category 1 colonies, akin to self-governing dominions within the British Empire. The Transvaal and the Orange Free State, despite their established republics, were to be reclassified similarly, incorporating them into the envisioned federation. The remaining British holdings, largely under the control of the British South Africa Company, were to be governed as Category 3 territories, effectively placing them under the new state's jurisdiction. The new federation, Rhodes proposed, would be called the “Union of Greater Southern Africa.”

This grand scheme, however, was not without its challenges and detractors. The conflation of commercial interests, particularly the control over the burgeoning gold mining industry by Rhodes and his business partner Alfred Beit, with political governance further complicated the ethical considerations of such unification. Similar wrangles, like the extent of suffrage and the role of non-Europeans in the political process, continued to be a sticking point between the colonies.

Rhodes favoured a hardline strategy and the leadership of the new federation to be placed firmly in British hands, undermining the Boers and non-Europeans alike: the Cape was to host the Parliament of the proposed state, more seats would initially be given to the Cape Colony, and more profits from the British South Africa Company diverted to its projects. Once they learned of the plans, in November 1893, Paul Kruger, President of the South African Republic (ZAR), said, “it is a plan made by fools for the purposes of making fools of all of us.”

Alfred Milner, former editor of The Union, disgraced by the March Massacres, played a crucial role in the negotiations. His diplomatic skill and understanding of Unionist politics were instrumental in navigating the complex interplay of interests that characterized the discussions. The plan for unification under Unionism was a bold one, reflective of the era's imperialist ethos and the belief in the civilizing mission of the British Empire. It was a plan that sought not only to secure economic resources but also to assert political control to bring order to what was perceived as a fragmented and untamed landscape.

Yet, the path to such unification was fraught with obstacles. The Boer Republics valued their independence and were wary of British intentions, particularly in light of the Uitlander issue and the imposition of taxes on the gold industry. The political machinations required to bring these republics into the fold would necessitate a delicate balance of diplomacy and, perhaps, a measure of coercion. Chamberlain was unconvinced that such a peaceful unification could take place and was reluctant, with the precarious nature of European peace, to undertake a war with the Boer Republics to gain the territories. Equally, the Germans, a key ally, were fiercely against military action on the Boers. Salisbury, however, was more malleable to the idea.

Alfred Milner and British Officers in Cape Town, 1893

In the shadowed halls of power, where the fate of nations was often decided far from the public eye, a covert military strategy was taking shape that would dramatically alter the geopolitical landscape of Southern Africa. This plan, conceived with the tacit approval of Lord Salisbury, the Regent, aimed to forcibly advance the Unionisation of Southern Africa—a project of political amalgamation to extend British hegemony over the region.

Prime Minister Joseph Chamberlain, a man whose political acumen was matched by his imperial ambitions, was curiously left out of the loop regarding these clandestine maneuvers. Whether by design or oversight, the true extent of the military machinations was concealed from him, a testament to the complex interplay of personal rivalries and political stratagems within the upper echelons of British governance.

At the heart of this shadow campaign was Major-General Charles George Gordon, a figure of near-mythic reputation who had, in another reality, met his end in Sudan. Yet here, Gordon remained a pivotal figure, the Governor-General of the British colonies in Southern Africa, whose military prowess and imperial vision found resonance with Lord Salisbury's broader objectives. Gordon, alongside Salisbury, Alfred Milner, and Cecil Rhodes, formed a clandestine quartet, each driven by their own motivations but united in their commitment to the Unionisation plan. Salisbury, wary of Chamberlain's potential reservations and cognizant of the need for discretion, sought to leverage Gordon's military expertise to execute a plan reminiscent of the historical Jameson Raid.

The plan was audacious in its scope and simplicity: a rapid, decisive military action that would topple the existing structures of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, replacing them with a British-controlled federation. This swift strike would be justified as a necessary measure to protect British citizens and interests, particularly in light of the increasing tensions surrounding the Uitlander predicament and the economic allure of the gold mines.

Gordon, ever the soldier, understood the risks but was invigorated by the prospect of a united Southern Africa under the Union Jack. His support for the plan, however, was not merely about military conquest; it was about securing a lasting peace and order in a land he believed was destined for greater unity. Milner, the astute diplomat, played a vital role in shaping the political narrative that would accompany the military endeavour. His influence ensured that the operation, while aggressive in nature, would be cloaked in the language of liberation and progress, aligning it with the civilizing rhetoric that underpinned so much of British imperial ideology. He began to use his contacts at The Union to launch political attacks on Kruger and the Boer Republics. Rhodes, the final piece of this conspiratorial puzzle, brought to the table not only his considerable economic clout but also a charismatic zeal for imperial expansion. His involvement was crucial, providing both the financial resources and the strategic connections necessary to stage such an operation from within the Cape Colony.

As the plan took shape, it became a spectre hanging over the future of Southern Africa—a gambit that, if successful, would dramatically shift the balance of power in favour of the British Empire. Yet, such schemes are fraught with unpredictability, and the spectre of failure loomed large. The impending action, though hidden from Chamberlain and the wider world, would soon reveal itself on the stage of history, its consequences reverberating through the annals of imperial legacy.

Part 3 - Conclusion

Joseph Chamberlain's strategy toward India and Greater Southern Africa was characterized by its nuanced approach to colonial administration and its intention to foster stability through reform. Chamberlain's support for incrementally integrating the colonies into a federal union highlighted his belief in a structured yet flexible approach to empire-building. His understanding of the complexities of colonial governance was underscored by his willingness to implement changes that addressed the specific needs and aspirations of the colonial subjects, albeit within the limits of British imperial interests.However, Chamberlain's strategies were not without their problems. In India, while the establishment of the passage of the Indian Council Act of 1894 was seen as a progressive step, it was criticized for falling short of granting genuine autonomy. The measures, though extensive, were perceived as superficial by Indian nationalists who continued to clamour for complete self-governance. The Unionist reforms, despite their intent to 'kill nationalism with kindness,' were met with skepticism by figures like Dadabhai Naoroji, whose advocacy for Indian home rule persisted unabated, highlighting the limitations of Chamberlain's reformist agenda.

In Greater Southern Africa, Chamberlain's reluctance to embrace Cecil Rhodes's push for unification under a British-controlled federation stemmed from a cautious approach to colonial expansion. The divergence of views between Chamberlain and Salisbury on the use of military intervention to achieve political objectives in the region further complicated the situation. The secret military plans, resembling the historical Jameson Raid and orchestrated without Chamberlain's explicit knowledge, underscored the contentious nature of colonial policy and the potential for discord within the highest ranks of British political leadership.