Part 1: Africa Descending

Note that this timeline is "on pause" (read: discontinued until further notice, when I get motivation back again). Read here, and if you feel like it, enjoy an... interesting story

Me and my nation against the world.

Me and my clan against my nation.

Me and my family against my clan.

Me and my brother against my family.

Me against my brother.

- Somali proverb

Me and my clan against my nation.

Me and my family against my clan.

Me and my brother against my family.

Me against my brother.

- Somali proverb

Just as the Great African War that began with the Tutsi revolt and Rwandan invasion was preceded by the Masisi War, the Masisi War itself was preceded by a gradual breakdown of the political situation in Kivu. Decades of animosity between the Banyarwanda and the indigenous tribes, primarily the Hunde, were now resurfacing as the Zairean state under Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga slid into complete state collapse. The Zairean state lacked much control outside of its capital and major cities, especially in the eastern regions of the country, with the virtual disappearance of national government authority in the region allowing for a variety of other political factions to fill up the vacuum. As the Zairean state further receded, and it became clear that even the introduction of multiparty politics could not stop the state decay, the Banyarwanda, viewing themselves to be excluded constantly from the political environment of Zaire, began to resist Hunde dominance in the region.

Like the Hutu-dominated revolution in Rwanda three decades prior, a new Hutu-dominated revolution seemed to be forming in Kivu. The growing political organization of the Hutus in the region resulted in the Hundes successfully getting the Hutus to be kept out of the National Conference that Mobutu Sese Seko had set up, supposedly to form a democratic system in Zaire. In response to the Hutus' exclusion, they stopped paying taxes, continued the organization of their political movements, and truly pushing towards democratic elections that could finally remove the prolonged monopoly in Hunde power in the area. Some Zairean Tutsi also supported those efforts, but also tried to push for a way to keep the Hutus from gaining power in the region. Nevertheless, a broad opposition front to Hunde-allied dominance in the area had developed by this time.

When Jean-Pierre Kalumbo Mboho, the governor of North Kivu, visited Masisi and questioned the presence of the Banyarwanda in the area, the anti-Banyarwanda groups in the area must have been emboldened to launch the opening salvo of the Masisi War, and, to some, the Great African War as a whole. The violence began March 20, 1993, and would continue until it was worsened by the Hutu refugee crisis in 1994-1995, and subsequently subsumed by greater violence beginning with the Banyalumenge revolt and the joint Rwandan-Ugandan-Burundian invasion in October of 1996.

Like the Hutu-dominated revolution in Rwanda three decades prior, a new Hutu-dominated revolution seemed to be forming in Kivu. The growing political organization of the Hutus in the region resulted in the Hundes successfully getting the Hutus to be kept out of the National Conference that Mobutu Sese Seko had set up, supposedly to form a democratic system in Zaire. In response to the Hutus' exclusion, they stopped paying taxes, continued the organization of their political movements, and truly pushing towards democratic elections that could finally remove the prolonged monopoly in Hunde power in the area. Some Zairean Tutsi also supported those efforts, but also tried to push for a way to keep the Hutus from gaining power in the region. Nevertheless, a broad opposition front to Hunde-allied dominance in the area had developed by this time.

When Jean-Pierre Kalumbo Mboho, the governor of North Kivu, visited Masisi and questioned the presence of the Banyarwanda in the area, the anti-Banyarwanda groups in the area must have been emboldened to launch the opening salvo of the Masisi War, and, to some, the Great African War as a whole. The violence began March 20, 1993, and would continue until it was worsened by the Hutu refugee crisis in 1994-1995, and subsequently subsumed by greater violence beginning with the Banyalumenge revolt and the joint Rwandan-Ugandan-Burundian invasion in October of 1996.

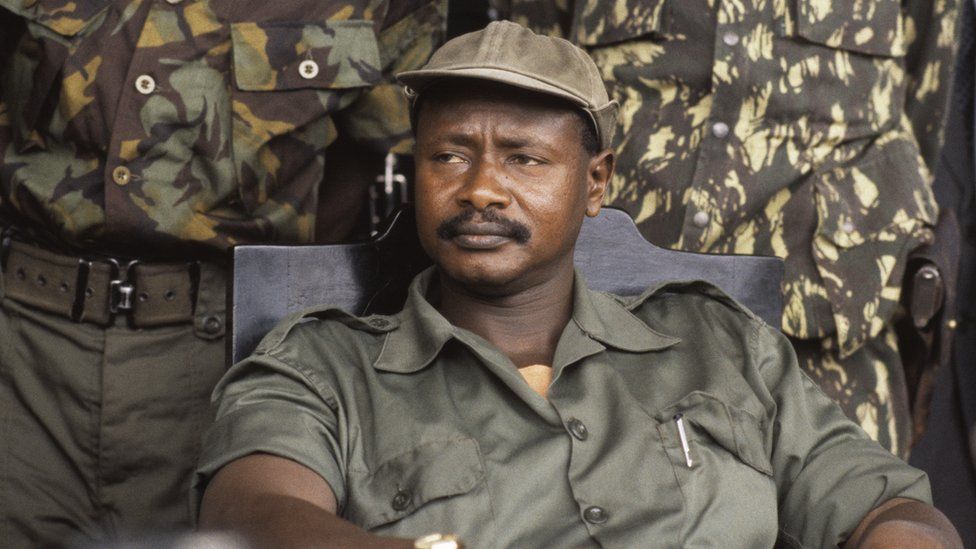

The early- to mid-1990s saw Uganda sitting at a crucial point in its lifetime. It bordered no friendly state- to the north was Sudan, who was in an undeclared war with Uganda, to the west was Zaire, a near-collapsed state still capable of backing the Ugandan opposition, to the south were Rwanda, angered over Uganda's support for Rwandan Tutsi, and Tanzania, largely indifferent to the new Ugandan government, while to the east was Kenya, with whom Museveni's Uganda had clashed with frequently. In addition, a rebellion waged by a myriad of armed factions united solely in their... interesting... ideologies (Christian theocracy), their Acholi ethnicity, and their opposition to the NRM government, had destabilized northern Uganda quite a bit, with help from Zaire and Sudan, and some even from Kenya.

Yoweri Museveni saw this situation exactly as it was- untenable. And he knew that if his government didn't have friends, they had to make some.

The worst days of the SPLA, 1991-1992, were ended with Ugandan involvement in the area, organizing the SPLA and reconciling its two factions to focus on defeating the Sudanese government. The newly-unified SPLA soon was able to take over all of southern Sudan again, save for major besieged cities, like Juba. In Rwanda, the Ugandans organized the Tutsi-led Patriotic Front to launch its invasion in October of 1990. It would then monitor its progress throughout the civil war and soon ensure a speedy victory with the beginning of the 1994 genocide. It then shifted attention to Zaire, initially joining Rwanda in invading the eastern regions to establish a buffer, before eventually allowing Zaireans to overthrow the government on their own. And in Kenya, it established a brief buffer territory in Kenyan territory to stop Kenyan support for the Ninth of October Movement.[1]

By the time the calendar had flipped to January of 1997, Museveni had essentially formed two new friendly polities to his north and south, and two buffer territories to his east and west that mostly succeeded with their goals. This allowed for the complete isolation of all rebel groups in Uganda from outside support, which they were dependent on rather than civilian support as the Ugandan government successfully appealed to the northern population to support the new system of government, or at least to not rebel and to instead participate in a genuine democracy. Save for the Lord's Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, most groups were destroyed. Maintaining this situation as it became the new challenge for Museveni, especially as the 1996 conflict was initiated. Museveni, although often overshadowed by Paul Kagame, was truly the most major player in the conflict, as he propped up or helped prop up many of the involved factions, more so than Kagame's Rwanda.

Yoweri Museveni saw this situation exactly as it was- untenable. And he knew that if his government didn't have friends, they had to make some.

The worst days of the SPLA, 1991-1992, were ended with Ugandan involvement in the area, organizing the SPLA and reconciling its two factions to focus on defeating the Sudanese government. The newly-unified SPLA soon was able to take over all of southern Sudan again, save for major besieged cities, like Juba. In Rwanda, the Ugandans organized the Tutsi-led Patriotic Front to launch its invasion in October of 1990. It would then monitor its progress throughout the civil war and soon ensure a speedy victory with the beginning of the 1994 genocide. It then shifted attention to Zaire, initially joining Rwanda in invading the eastern regions to establish a buffer, before eventually allowing Zaireans to overthrow the government on their own. And in Kenya, it established a brief buffer territory in Kenyan territory to stop Kenyan support for the Ninth of October Movement.[1]

By the time the calendar had flipped to January of 1997, Museveni had essentially formed two new friendly polities to his north and south, and two buffer territories to his east and west that mostly succeeded with their goals. This allowed for the complete isolation of all rebel groups in Uganda from outside support, which they were dependent on rather than civilian support as the Ugandan government successfully appealed to the northern population to support the new system of government, or at least to not rebel and to instead participate in a genuine democracy. Save for the Lord's Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, most groups were destroyed. Maintaining this situation as it became the new challenge for Museveni, especially as the 1996 conflict was initiated. Museveni, although often overshadowed by Paul Kagame, was truly the most major player in the conflict, as he propped up or helped prop up many of the involved factions, more so than Kagame's Rwanda.

Rwanda and Burundi both had been messes since independence. Rwanda's independence was marked by the mass murder of Tutsis, it's first war- the Bugesera invasion- ended with the mass murder of Tutsis, and its Civil War ended with the mass murder of Tutsis. It seemed as if qualms between Hutu communities could be settled by persecuting Tutsis. Their position in Rwanda quite awful, Tutsis fled to Uganda, Burundi, Tanzania, the Congo, anywhere they were not persecuted. Meanwhile, in Burundi, Tutsis led the country, and welcomed Rwandan Tutsis to the point that Burundi actually backed a Rwandan Tutsi invasion of Rwanda in December 1963's Bugesera invasion. It, in turn, oppressed Hutus, including during the Ikiza of 1972, when hundreds of thousands of Hutu intellectuals were murdered after a failed Hutu revolt.

Neither status quo would last, though. Rwandan Tutsis assisted heavily in bringing Yoweri Museveni's National Resistance Movement/Army to power in Uganda, so Museveni helped them get back into power in Rwanda, giving them weapons and some manpower assistance for their October 1990 invasion of Rwanda. The initial invasion by the Tutsis, united under the Rwandan Patriotic Front, failed to capture Kigali, but established control over wide swaths of northern Rwanda. It attracted many Rwandan Tutsis, most of whom fled to the "liberated areas" of the RPF, where they saw themselves as safe. 1993 uprisings sparked by RPF operatives in areas with higher concentrations of Tutsis, like southern and southwestern Rwanda, soon officially aligned themselves with the RPF.[1]

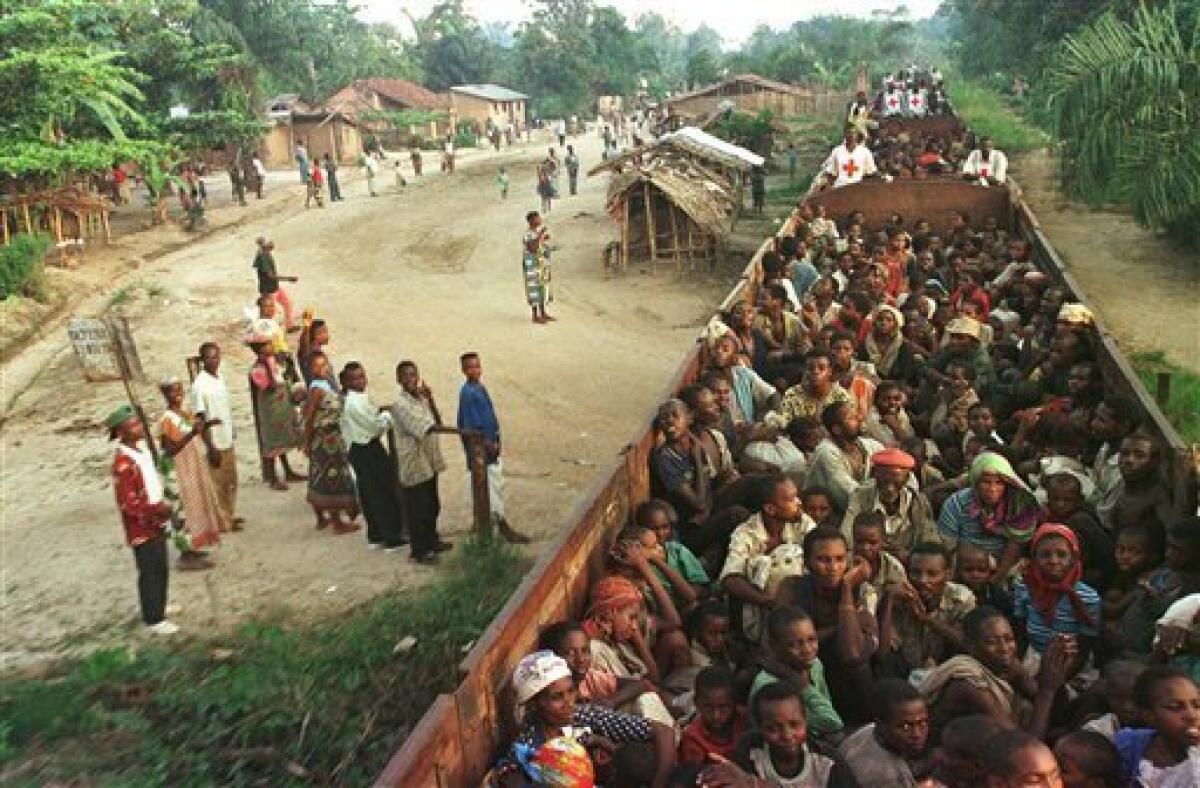

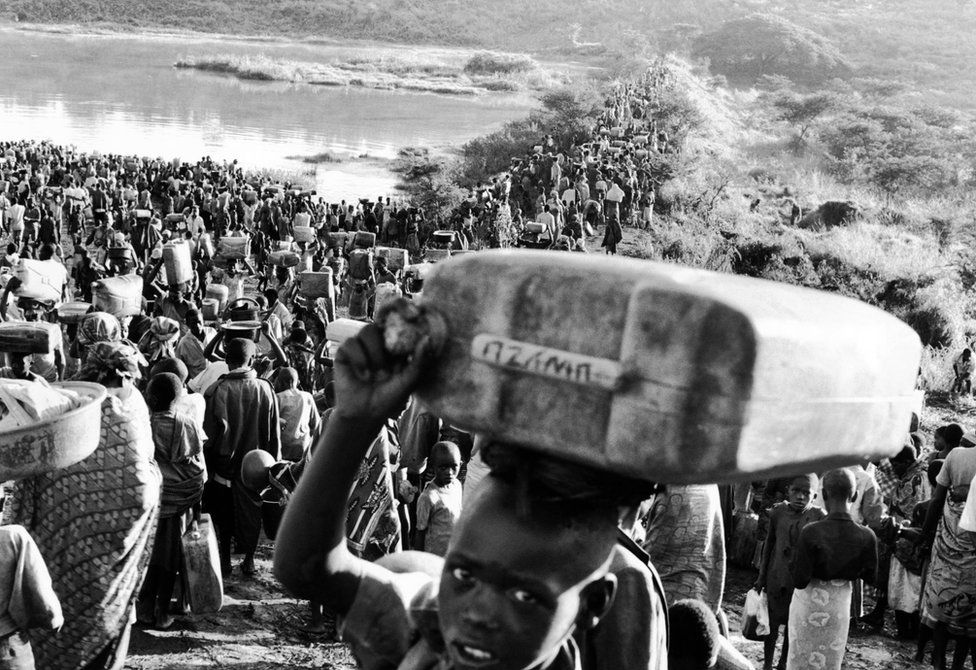

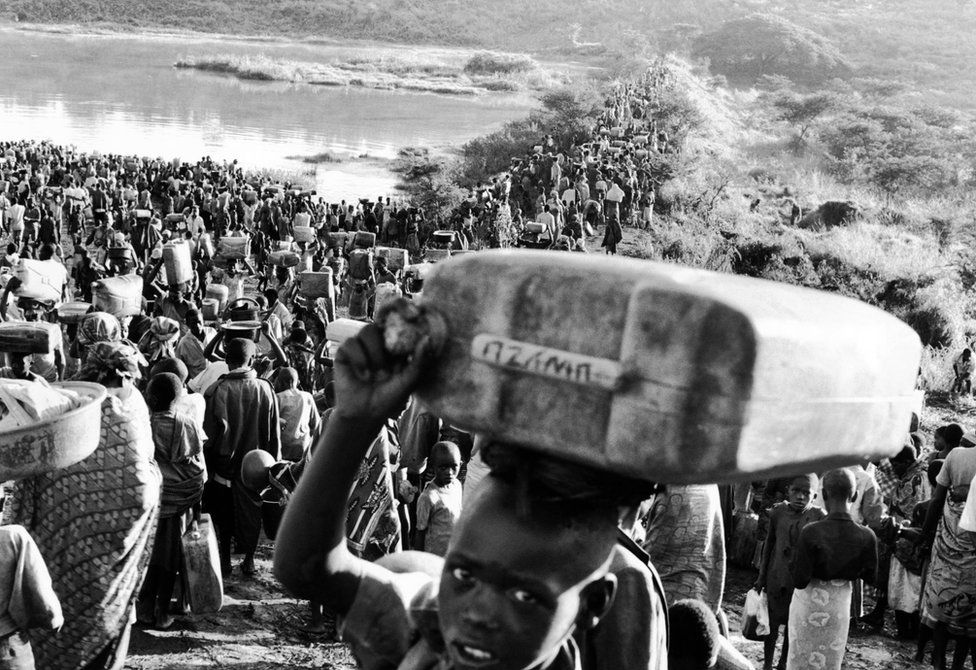

President Juvenal Habyarimana, seen as too lenient to the Tutsi rebels due to his peace offerings after the 1993 uprisings, was ousted from power in a bloody coup committed by Hutu extremists on February 28, 1994, and nearly killed before he fled to the next-best faction for support- the RPF itself.[2] The RPF detained him as a prisoner until the war was over. The new regime, led by Théoneste Bagosora, began a genocide of all Rwandan Tutsis still in areas under government control. The genocide lasted two weeks before the RPF seized Kigali in March.[1] Bagosora's government fled to Zaire, with hundreds of thousands of Hutus following behind him, fearing retribution for the mass killings.

Meanwhile, to the south, Burundi had gotten a start to armed violence a little earlier. The last in a series of Tutsi military dictatorships, Pierre Buyoya's government saw the formation of a democratic process that some Hutu militant groups opted to participate in. The 1993 elections brought the Hutu President Melchior Ndadaye to power, and brought about the belief that genuine democracy was finally arriving for the Burundian people- this belief was done away with violently with the October 1993 coup d'etat by Tutsi extremists opposed to Ndadaye's rule. They brutally bayoneted the President to death, and took power for themselves. Hutu anger at the events initiated ethnic violence targeted at Tutsis, at a scale never seen since the Ikiza of 1972. Over a hundred thousand Burundians died, Hutus and Tutsis alike, in the opening salvo of Burundi's civil war. A series of attempts at national governments, often made up of both Hutus and Tutsis, failed to stop the violence committed by both Hutu and Tutsi radicals, only slowing down the large-scale massacres of 1993. The RPF-led Rwandan government would use Hutu militant attacks in Burundi as a reason to operate in Zaire in 1996-1997, as to deny the militants a base to fight in.

Neither status quo would last, though. Rwandan Tutsis assisted heavily in bringing Yoweri Museveni's National Resistance Movement/Army to power in Uganda, so Museveni helped them get back into power in Rwanda, giving them weapons and some manpower assistance for their October 1990 invasion of Rwanda. The initial invasion by the Tutsis, united under the Rwandan Patriotic Front, failed to capture Kigali, but established control over wide swaths of northern Rwanda. It attracted many Rwandan Tutsis, most of whom fled to the "liberated areas" of the RPF, where they saw themselves as safe. 1993 uprisings sparked by RPF operatives in areas with higher concentrations of Tutsis, like southern and southwestern Rwanda, soon officially aligned themselves with the RPF.[1]

President Juvenal Habyarimana, seen as too lenient to the Tutsi rebels due to his peace offerings after the 1993 uprisings, was ousted from power in a bloody coup committed by Hutu extremists on February 28, 1994, and nearly killed before he fled to the next-best faction for support- the RPF itself.[2] The RPF detained him as a prisoner until the war was over. The new regime, led by Théoneste Bagosora, began a genocide of all Rwandan Tutsis still in areas under government control. The genocide lasted two weeks before the RPF seized Kigali in March.[1] Bagosora's government fled to Zaire, with hundreds of thousands of Hutus following behind him, fearing retribution for the mass killings.

Meanwhile, to the south, Burundi had gotten a start to armed violence a little earlier. The last in a series of Tutsi military dictatorships, Pierre Buyoya's government saw the formation of a democratic process that some Hutu militant groups opted to participate in. The 1993 elections brought the Hutu President Melchior Ndadaye to power, and brought about the belief that genuine democracy was finally arriving for the Burundian people- this belief was done away with violently with the October 1993 coup d'etat by Tutsi extremists opposed to Ndadaye's rule. They brutally bayoneted the President to death, and took power for themselves. Hutu anger at the events initiated ethnic violence targeted at Tutsis, at a scale never seen since the Ikiza of 1972. Over a hundred thousand Burundians died, Hutus and Tutsis alike, in the opening salvo of Burundi's civil war. A series of attempts at national governments, often made up of both Hutus and Tutsis, failed to stop the violence committed by both Hutu and Tutsi radicals, only slowing down the large-scale massacres of 1993. The RPF-led Rwandan government would use Hutu militant attacks in Burundi as a reason to operate in Zaire in 1996-1997, as to deny the militants a base to fight in.

The unity of black Africans and Arabs into one country failed spectacularly in Sudan. Its first civil war saw a near-constant series of attacks by southern Sudanese insurgents seeking to separate southern Sudan from the north, which had traditionally been dominated by Arabs. This issue was fixed temporarily in the 1970s with the Addis Ababa Agreement, giving southern Sudan an autonomous region. This, however, did not completely fix all the agitations of the southern Sudanese- the Anyanya units who fought in the first civil war were not successfully integrated into the military, resources in the south like oil were taken away to the north, and there was continued marginalization of the southerners. Following the 1983 Bor mutiny, the Southern Sudan Autonomous Region was abolished, and Islamic sharia law was imposed throughout the country, in an effort to please the Islamic fundamentalists who opposed the Addis Ababa Agreement.

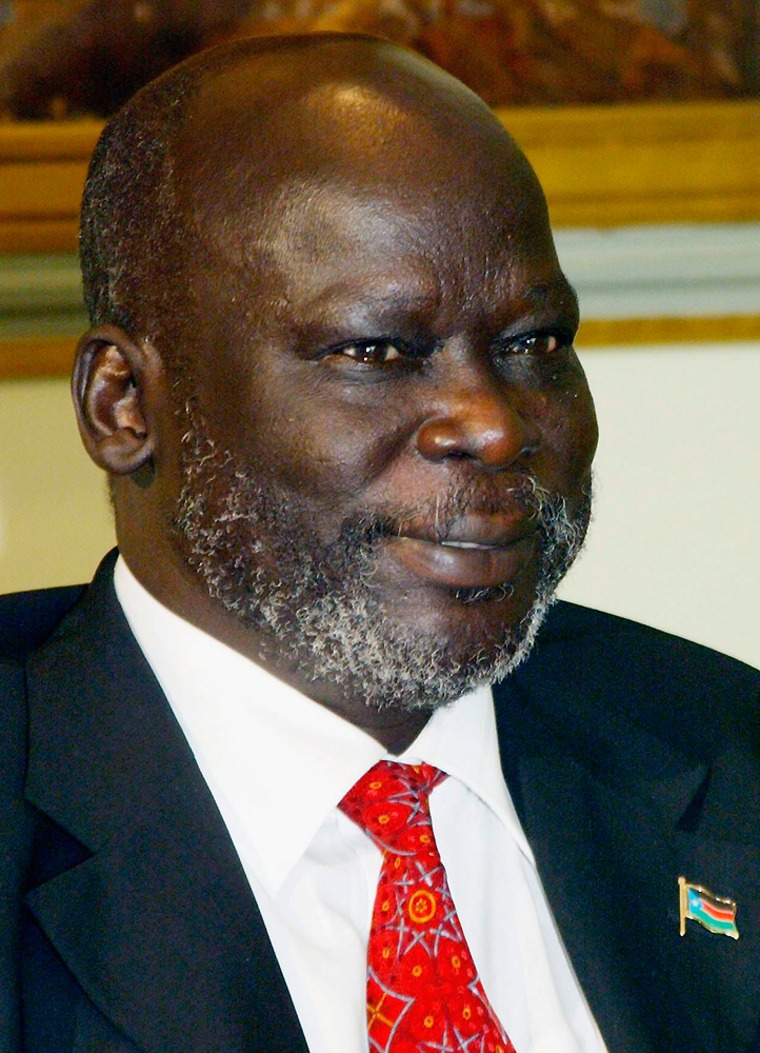

The mutineers at Bor were led by John Garang, who united the forces into the Sudanese People's Liberation Army. Garang was interesting in that he did not advocate for southern secession- instead, he wanted a united, democratic, secular, probably socialist, and generally New Sudan accepting towards all religions and races. He saw the Khartoum government as divisive, and his goal was to make a government that'd keep the Sudan unified. This, or to pressure the existing government to make changes that'd make unity attractive, while allowing the southern Sudan to choose whether they wanted to stay in Sudan or leave- if the government failed to make unity look viable for the south, then the south would leave, and no one in the SPLA would shed tears about it. Garang wanted to see a unified Sudan, but only if it was beneficial for all races in the nation.

Due to his vision for a New Sudan, Garang never limited his operations to just the south. After his sweeping mid- to late-80s offensives captured nearly all of southern Sudan save for besieged government garrison towns like Juba, he did not hesitate to operate out of Sudan and into places like Darfur, Kordofan, and the east. In addition, he wasn't exactly humanitarian for the population- he was supplied by communist Ethiopia and the government forces were very weak, so the SPLA committed human rights violations that often alienated them from the civilian population, and they didn't care, because they did not rely on the civilians at the time- they had enough weaponry to perform their operations on their own.

Then communist Ethiopia fell. And then the Sudanese government was ousted & replaced by an Islamist one seeking to crush the south completely. And then the SPLA split into two factions, the mainstream one led by Garang and based out of Torit (called SPLA-Mainstream or SPLA-Torit), and the dissenters that split in their Nasir Declaration (called SPLA-Nasir). And then Sudanese counteroffensives in 1991 and 1992 took advantage of this to make sweeping gains against the SPLA. And suddenly Garang relied on the civilian population that he had often repressed years before to survive. He was able to reconcile relatively well, and regained some territory, but it wasn't until years later, during the opening stages of the Great African War and with Ugandan assistance, that the SPLA would be able to make a full rebound. For now, the conflict stagnated.

The mutineers at Bor were led by John Garang, who united the forces into the Sudanese People's Liberation Army. Garang was interesting in that he did not advocate for southern secession- instead, he wanted a united, democratic, secular, probably socialist, and generally New Sudan accepting towards all religions and races. He saw the Khartoum government as divisive, and his goal was to make a government that'd keep the Sudan unified. This, or to pressure the existing government to make changes that'd make unity attractive, while allowing the southern Sudan to choose whether they wanted to stay in Sudan or leave- if the government failed to make unity look viable for the south, then the south would leave, and no one in the SPLA would shed tears about it. Garang wanted to see a unified Sudan, but only if it was beneficial for all races in the nation.

Due to his vision for a New Sudan, Garang never limited his operations to just the south. After his sweeping mid- to late-80s offensives captured nearly all of southern Sudan save for besieged government garrison towns like Juba, he did not hesitate to operate out of Sudan and into places like Darfur, Kordofan, and the east. In addition, he wasn't exactly humanitarian for the population- he was supplied by communist Ethiopia and the government forces were very weak, so the SPLA committed human rights violations that often alienated them from the civilian population, and they didn't care, because they did not rely on the civilians at the time- they had enough weaponry to perform their operations on their own.

Then communist Ethiopia fell. And then the Sudanese government was ousted & replaced by an Islamist one seeking to crush the south completely. And then the SPLA split into two factions, the mainstream one led by Garang and based out of Torit (called SPLA-Mainstream or SPLA-Torit), and the dissenters that split in their Nasir Declaration (called SPLA-Nasir). And then Sudanese counteroffensives in 1991 and 1992 took advantage of this to make sweeping gains against the SPLA. And suddenly Garang relied on the civilian population that he had often repressed years before to survive. He was able to reconcile relatively well, and regained some territory, but it wasn't until years later, during the opening stages of the Great African War and with Ugandan assistance, that the SPLA would be able to make a full rebound. For now, the conflict stagnated.

Those are a lot of conflicts, of course. Does it seem like they could become easily intertwined with one another? It does, and it would happen. What were once individual conflicts would soon merge into a long, deadly "frontline"- not just in the Great Lakes region, but spanning from the deserts of the Sahel to the jungles of Katanga, the savannah of Centrafrique to the mountains of Angola. A catastrophe on a continental scale was to unfold, driven by an insatiable desire of resources by both the warlords dressed up in camo and the politicians dressed up in suits and ties, all while the people were stomped on indefinitely. The world would gaze upon the violence in utter awe as soldiers of all sides marched into enemy villages and performed pillagings and massacres brutal enough so that it drew memories of the medieval era.

This is not the tragedy of one country, but a continent. It is a tale of the oppressed and the oppressors, and how so often it seemed like one group could be oppressed one day and oppressors the next. It is the tale of the world's largest, deadliest, and most destructive war since World War Two, of how the world could only watch in horror at battles raging on for months and incinerating cities in a deadly inferno of fire and lead, of how hundreds of thousands of young men could be indoctrinated so thoroughly to murdering foreigners for their country, and then murdering their countrymen for their tribe, and then murdering their tribe members for the family, and then murdering their family members for their brother, and them murdering their brother for themselves.

This is not the tragedy of one country, but a continent. It is a tale of the oppressed and the oppressors, and how so often it seemed like one group could be oppressed one day and oppressors the next. It is the tale of the world's largest, deadliest, and most destructive war since World War Two, of how the world could only watch in horror at battles raging on for months and incinerating cities in a deadly inferno of fire and lead, of how hundreds of thousands of young men could be indoctrinated so thoroughly to murdering foreigners for their country, and then murdering their countrymen for their tribe, and then murdering their tribe members for the family, and then murdering their family members for their brother, and them murdering their brother for themselves.

I've an idea as to how this'll end- in the Congo, the same thing as reached in OTL- in Sudan, a New Sudan being formed and then South Sudan still seceding- in Angola, a stalemate, and in Burundi, OTL's resolution.

About exact PoDs, I'm not sure- I initially wanted to expand Ugandan involvement here, but it doesn't align with my eventual plans for the TL. Initially a Ugandan invasion of Kenya occurred here, but that makes no sense so I'm removing it. All info on PoDs will be provided in footnotes when they come about.

Will I finish this? I don't know. I hope I will. It sounds like a genuinely interesting concept, the Congo Wars being so much more wide-reaching and geopolitically significant than they were in OTL.

Specific PoDs:

[1] Such uprisings never materialized in OTL. As such, the genocide was resolved by the RPF quicker.

[2] In OTL, Habyarimana was killed by a missile attack- ITTL, he was ousted by Hutu extremists. His continued existence as a major influence among Hutus is the reason for this PoD, a vain attempt to make Hutus like the new government a bit more

About exact PoDs, I'm not sure- I initially wanted to expand Ugandan involvement here, but it doesn't align with my eventual plans for the TL. Initially a Ugandan invasion of Kenya occurred here, but that makes no sense so I'm removing it. All info on PoDs will be provided in footnotes when they come about.

Will I finish this? I don't know. I hope I will. It sounds like a genuinely interesting concept, the Congo Wars being so much more wide-reaching and geopolitically significant than they were in OTL.

Specific PoDs:

[1] Such uprisings never materialized in OTL. As such, the genocide was resolved by the RPF quicker.

[2] In OTL, Habyarimana was killed by a missile attack- ITTL, he was ousted by Hutu extremists. His continued existence as a major influence among Hutus is the reason for this PoD, a vain attempt to make Hutus like the new government a bit more

Last edited: