You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Lights of Liberty - a counterfactual history

- Thread starter Widukind

- Start date

Man, I don't know why I haven't paid attention to this TL yet, but I am now resolved to fix that oversight; consider me SUBSCRIBED! Most recently, as both a fan of Dutch culture/language and a proponent of bearing arms, Batavia is truly awesome to me.

Glad you're enjoying it so much.

Two questions/notes while I think about it;

-Is America ITTL a multi-lingual entitiy, or is English pushed as the "one true tongue" like in OTL? I'd think the influence of Sanssouci and Co. plus Montreal's inclusion might make French more "legitimate" as a side language (not to mention having Prussian acting as an example for the young country, and how that might affect attitudes towards German). And,

-Whatever you're planning to do with the Southern states (not that I'm necessarily advocating a split-up of America, IDK what you really have in mind yet), I beseech you please keep Virginia in the fold with them. It's bad enough how it's evolved with parts of it being a giant D.C./Federal suburb IOTL

TTL's United States are considerably more multi-lingual. Montréal is officially Francophone, with English as a second language. The top schools/colleges throughout the US include French in their curriculum. There is no official language, and documents by the General Government in Philadelphia are translated into French before publication in Montréal.

Religious tolerance is also rather developed, compared to OTL. Like IOTL, it is allowed for states to establish a state church, but freedom to worship regardless of creed is pretty much a given. Jefferson and Madison advocate this loudly, as they did IOTL. (Interestingly, the northeastern states are the more conservative ones, as they were IOTL during this period. The northeastern federalists are generally the most conservative politicians, whereas Virginia is viewed as the most progressive state.)

As for what I'm planning for the South in general and Virginia in particular... well, I'm not going to tell yet. But the above should make it clear that at this time, Virginia is the most Democratic-Republican state of all. There is also no D.C., because the capital remains in Philadelphia. Williamsburg (rather than Richmond) and Norfolk are growing quite rapidly.

Looking forward to the next update

I am confident that the next update will be ready on friday.

Glad you're enjoying it so much.Including the Batavian Republic / Patriotic Movement was something I wanted from the start. I've lived most of my life in the Netherlands, and even in Dutch history lessons the Bataafsche Tijd gets ignored all too often. Most TLs here never even mention it, and it's such an interesting period in Dutch history! I couldn't leave it out.

Cool, I also have almost never seen that concept used much in other TLs either. I can't say I've ever been to the Netherlands, although I have been to the Netherlands Antilles if that counts! Anyway, will the capital of Batavia still be Den Haag or will it be somewhere else? I can't recall that particular point differing during Netherland's change of government.

TTL's United States are considerably more multi-lingual. Montréal is officially Francophone, with English as a second language. The top schools/colleges throughout the US include French in their curriculum. There is no official language, and documents by the General Government in Philadelphia are translated into French before publication in Montréal.

Interesting, I guess the US in TTL took French to heart as a cornerstone of neo-Liberalism to heart

Religious tolerance is also rather developed, compared to OTL. Like IOTL, it is allowed for states to establish a state church, but freedom to worship regardless of creed is pretty much a given. Jefferson and Madison advocate this loudly, as they did IOTL. (Interestingly, the northeastern states are the more conservative ones, as they were IOTL during this period. The northeastern federalists are generally the most conservative politicians, whereas Virginia is viewed as the most progressive state.)

I actually forgot to ask about that, but also good to hear. The distribution of conservative vs. progressive attitudes towards religion doesn't surprise me since AIUI that didn't really switch around till the 1830s-1840s in OTL. I would ask about attitudes about ethnicity but, given the pattern the US has followed thus far and your comments in the past about slavery's fate, I'll just shut up and let the TL do the talking about that

As for what I'm planning for the South in general and Virginia in particular... well, I'm not going to tell yet. But the above should make it clear that at this time, Virginia is the most Democratic-Republican state of all. There is also no D.C., because the capital remains in Philadelphia. Williamsburg (rather than Richmond) and Norfolk are growing quite rapidly.

Well, whatever happens (hopefully a little more clarity is forthcoming come Friday

Cool, I also have almost never seen that concept used much in other TLs either. I can't say I've ever been to the Netherlands, although I have been to the Netherlands Antilles if that counts! Anyway, will the capital of Batavia still be Den Haag or will it be somewhere else? I can't recall that particular point differing during Netherland's change of government.

Yes, that counts!

As for the capital... It's a funny thing, but Den Haag / The Hague has actually never been the Dutch capital. The capital is Amsterdam, but the central government is situated in Den Haag. (Mind you, this is something many Dutch people aren't actually aware of, either...) IOTL, the government was situated in Amsterdam only when Napoleon briefly installed his brother as king. I can safely say that the government will remain in Den Haag ITTL, while Amsterdam remains the official capital.

Well, whatever happens (hopefully a little more clarity is forthcoming come Friday) I do like the fact that the US capital is still in Philadelphia. Frankly I've always thought it should've stayed there in OTL for several reasons, one of which being that D.C. won't end up turning the Potomac into their personal waterway. I will say that your comment about the Democratic-Republican Party does fill me with hope, either way

. Also, kudos to keeping the state capital in Williamsburg, I always loved visiting it when I was growing up.

It'll be a while before this TL visits America again. The current part is nearing its end, but the next part will be about Britain, and the one after that will deal with yet more European affairs. After that: back to the United States.

Focussing back on Europe works for me, too. After all, the events to come in France seem likely to be quite different from OTL (I wonder whether a certain Corsican will play any role in it, however small...), not to mention the after-effects of Britain's worse showing in the Revolutionary War and events going on in Prussia.

I'd actually gotten The Hague and Amsterdam switched, I thought the former was the "capital" with Amsterdam the seat of governmental bureaucracy . Thanks for correcting me, and in any event it's good that we won't have any of that monarchical stuff in Netherland (FWIW I find calling it "the Netherlands" clunky after using it constantly, is that weird?), that's for the Brandenburgers and Brits, a-thank-ya-very-much

. Thanks for correcting me, and in any event it's good that we won't have any of that monarchical stuff in Netherland (FWIW I find calling it "the Netherlands" clunky after using it constantly, is that weird?), that's for the Brandenburgers and Brits, a-thank-ya-very-much  .

.

I'd actually gotten The Hague and Amsterdam switched, I thought the former was the "capital" with Amsterdam the seat of governmental bureaucracy

Focussing back on Europe works for me, too. After all, the events to come in France seem likely to be quite different from OTL (I wonder whether a certain Corsican will play any role in it, however small...), not to mention the after-effects of Britain's worse showing in the Revolutionary War and events going on in Prussia.

All these things will be addressed in parts VII and VIII. And yes, a certain Corsican will be making an appearance. It won't even be a small role, though it will be... different.

I'd actually gotten The Hague and Amsterdam switched, I thought the former was the "capital" with Amsterdam the seat of governmental bureaucracy. Thanks for correcting me, and in any event it's good that we won't have any of that monarchical stuff in Netherland (FWIW I find calling it "the Netherlands" clunky after using it constantly, is that weird?), that's for the Brandenburgers and Brits, a-thank-ya-very-much

.

Yeah, "the Nederlands" is kind of a strange thing. Of course, they used to be sovereign, confederated provinces, and that's how it started. The Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. Officially it's still the Kingdom of the Netherlands, but you probably know that the Dutch just call it Nederland (singular).

As for the monarchy... I'm not a fan, either. But that's what makes alternate history fun. We can explore the many, many roads not taken.

Yeah, "the Nederlands" is kind of a strange thing. Of course, they used to be sovereign, confederated provinces, and that's how it started. The Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. Officially it's still the Kingdom of the Netherlands, but you probably know that the Dutch just call it Nederland (singular).

As for the monarchy... I'm not a fan, either. But that's what makes alternate history fun. We can explore the many, many roads not taken.

-I suppose "Holland" works in English as an alternative for "The Netherlands", but I know that's only one part of the country, and it must get pretty old hearing it from English-speakers (I can sympathize; I get ticked if a non-American calls me a Yank since I'm from VA). I don't wanna go too far into possible future-update material, but how different (if at all) do you think Batavia's attitude towards its external territories will be? Also, I couldn't remember reading this in the last couple updates but where does Belgium/Flanders fall in the scheme of Franco-Dutch events of late?

-Also, will we be seeing more information on Prussia soon, given the massive changes already occurring in France and the Low Countries? I figure they'd still be on their guard against Austria (as an aside, does anyone else find it weird that English calls it "Austria" despite being a Germanic language, whereas French refers to it as "Autriche" despite being a Romance language?) or possibly Russia. Then again, your little reference about a certain Corsican might be something that has something to do with this little piece of history to come...

-Regarding the US map, is there any reason why North Carolina owns all of the Jackson Purchase, yet Virginia dips down along either the Cumberland or Duck River and then back northward? I'm not complaining, just curious.

-I suppose "Holland" works in English as an alternative for "The Netherlands", but I know that's only one part of the country, and it must get pretty old hearing it from English-speakers (I can sympathize; I get ticked if a non-American calls me a Yank since I'm from VA).

Don't worry about it. I'm not from the province of either North or South Holland and will never refer to the country as "Holland," but considering the modest size of the country, it's hardly surprising that many foreigners tend to refer to it that way. The average Dutchmen would in turn be unable to tell you upon which continent the Shenandoah Valley is located, for instance. Let alone point it out on a map.

I don't wanna go too far into possible future-update material, but how different (if at all) do you think Batavia's attitude towards its external territories will be? Also, I couldn't remember reading this in the last couple updates but where does Belgium/Flanders fall in the scheme of Franco-Dutch events of late?

The current situation in the Austrian Netherlands will be addressed in the next update. The other thing I cannot talk about quite yet.

-Also, will we be seeing more information on Prussia soon, given the massive changes already occurring in France and the Low Countries? I figure they'd still be on their guard against Austria (as an aside, does anyone else find it weird that English calls it "Austria" despite being a Germanic language, whereas French refers to it as "Autriche" despite being a Romance language?) or possibly Russia. Then again, your little reference about a certain Corsican might be something that has something to do with this little piece of history to come...

Prussia and Austria will be covered in future parts, but not too far in the future. Certain things are going on in Russia, but that will be dealt with at a later stage.

(Incidentally, I suppose the name Austria is a Latinized form of the German name, "Österreich," which means "Eastern Realm." In French "Autriche" you see both the Germanic and Romance influences.)

-Regarding the US map, is there any reason why North Carolina owns all of the Jackson Purchase, yet Virginia dips down along either the Cumberland or Duck River and then back northward? I'm not complaining, just curious.

Honestly, it's somewhat random, although it's random on purpose. The Continental Congress is authorized to settle border disputes, and with TTL's United States diverging from OTL right from the start, I just didn't believe those matters would be settled in the exact same way. Some borderlines just make sense and will likely show up in many TLs, but I hate it when the exact OTL borders just show up in an ATL where butterflies are already hard at work.

This is simply one way that border could have ended up, and I just went with it.

Last edited:

Don't worry about it. I'm not from the province of either North or South Holland and will never refer to the country as "Holland," but considering the modest size of the country, it's hardly surprising that many foreigners tend to refer to it that way. The average Dutchmen would in turn be unable to tell you upon which continent the Shenandoah Valley is located, for instance. Let alone point it out on a map.

-I guess I can see how that works. I will just have to wait on the other stuff, which is no problem for me (tomorrow's Friday after all

Honestly, it's somewhat random, although it's random on purpose. The Continental Congress is authorized to settle border disputes, and with TTL's United States diverging from OTL right from the start, I just didn't believe those matters would be settled in the exact same way. Some borderlines just make sense and will likely show up in many TLs, but I hate it when the exact OTL borders just show up in an ATL where butterflies are already hard at work.

This is simply one way that border could have ended up, and I just went with it.Several other borders also differ somewhat from OTL. Anyway, the western states are going to be quite different. One thing the Democratic-Republican wanted IOTL was to create as many states in the west as possible, and as soon as possible. These would likely be solidly Democratic-Republican. With the number of states all-important in TTL's one-state-one-vote Congress, expect Jefferson to really push for new states to be carved out in the west as early on as reasonably possible.

-Fair enough, I do enjoy little changes here and there to maps and borders. Looking at the map, does that mean that *Nashvile and *Clarksville would be in NC, or VA? It's hard to tell with the USA map scale as shown. As for the states thing, I will take that as a bit of foreshadowing and leave it at that...although it IS Jefferson in the Consulate

I noticed that not ALL Southern states abstained from approving the Declaration of Independence ITTL despite the stronger anti-slavery wording...

There are no minutes of the debate, so the whole idea of "the South threatened not to accept it unless the part about slavery was removed!" is really conjectural. From the various notes and recollections of those present (including Jefferson), the central argument against was actually borne of apprehension at the idea of severing ties with Britain. Edward Rutledge of South Carolina is often accused of being the one to oppose the condemnation of slavery (see, for instance, the musical, 1776). In reality, he is not mentioned once, by anyone, as opposing the Declaration on those grounds. South Carolina was mostly fearful that the time was not yet ripe for independence.

Nevertheless, there was certainly some friction in regards to the condemnation (it was removed, after all), and Jefferson mentions objections from Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina. So I could see the Carolinas abstaining from the vote. (Georgia could go either way, depending entirely on which delegates were sent, so I went with Georgia accepting the objection.) The Carolinas ITTL are not even truly opposed, but do not want to attach their "yea" to it, either. They wouldn't be too worried about the one paragraph condemning not even slavery, but the slave trade... vaguely. It was written by a guy who owned hundreds of slaves himself.

(Ah, Jefferson, if only you'd been a little more consistent in that regard, and just freed the lot of them, you'd have risen yet higher in my regard.)

Last edited:

There are no minutes of the debate, so the whole idea of "the South threatened not to accept it unless the part about slavery was removed!" is really conjectural. From the various notes and recollections of those present (including Jefferson), the central argument against was actually borne of apprehension at the idea of severing ties with Britain. Edward Rutledge of South Carolina is often accused of being the one to oppose the condemnation of slavery (see, for instance, the musical, 1776). In reality, he is not mentioned once, by anyone, as opposing the Declaration on those grounds. South Carolina was mostly fearful that the time was not yet ripe for independence.

Nevertheless, there was certainly some friction in regards to the condemnation (it was removed, after all), and Jefferson mentions objections from Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina. So I could see the Carolinas abstaining from the vote. (Georgia could go either way, depending entirely on which delegates were sent, so I went with Georgia accepting the objection.) The Carolinas ITTL are not even truly opposed, but do not want to attach their "yea" to it, either. They wouldn't be too worried about the one paragraph condemning not even slavery, but the slave trade... vaguely. It was written by a guy who owned hundreds of slaves himself.

(Ah, Jefferson, if only you'd been a little more consistent in that regard, and just freed the lot of them, you'd have risen yet higher in my regard.)

I actually forgot that much of what we know about the Convention came from second-hand information and/or personal notes. Really I think a lot of that attitude about the South's refusal to break away from Britain if slavery is damned is with hindsight and applying attitudes of the 1840s-50s backwards, but that's another discussion. The bottom line is that much of the south was looking out for their checkbooks (as was New York, apparently), or in South Carolina's case a question of timing.

In Georgia's case, I think people forget that it was mostly just a really thin strip of land at the time in terms of actual populated areas, and almost an extension of South Carolina. Once movement westward happens, who knows how different attitudes in the state towards slavery might develop if the spirit of the Enlightenment is that much stronger (especially with Virginia's Democratic-Republican political influence in the area also being strengthened)? But yeah, I see what you mean about the trade itself being damned rather than the institution on the whole...baby steps, I suppose. Jefferson was indeed a complicated dude, both here and IOTL.

I actually forgot that much of what we know about the Convention came from second-hand information and/or personal notes. Really I think a lot of that attitude about the South's refusal to break away from Britain if slavery is damned is with hindsight and applying attitudes of the 1840s-50s backwards, but that's another discussion. The bottom line is that much of the south was looking out for their checkbooks (as was New York, apparently), or in South Carolina's case a question of timing.

In Georgia's case, I think people forget that it was mostly just a really thin strip of land at the time in terms of actual populated areas, and almost an extension of South Carolina. Once movement westward happens, who knows how different attitudes in the state towards slavery might develop if the spirit of the Enlightenment is that much stronger (especially with Virginia's Democratic-Republican political influence in the area also being strengthened)? But yeah, I see what you mean about the trade itself being damned rather than the institution on the whole...baby steps, I suppose. Jefferson was indeed a complicated dude, both here and IOTL.

Yeah, I agree. On all of this.

For the moment, however, let us cast our attention back to France (and some other parts of Europe), in the penultimate installment of Part VI. Because it's friday. (Well, not all over the globe, I suppose, but it's friday where I live.) And I promised an update on friday. So let's find out what kind of a place the French Republic is shaping up to be, and what the rest of Europe feels about that.

---

The Declaration of the Rights of Humanity (adopted on the 26th of September, 1784):

I. Human beings are born and remain free and equal in rights. The aim of all political association must be the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of humanity. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

II. The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the individual. No body nor government may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the individual. [1]

III. Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law.

IV. Law can only prohibit such actions as are hurtful to the individual. Law may not be used to coerce individuals into any action against their will. Nothing may be prevented which is not forbidden by law.

V. No person shall be accused, arrested, or imprisoned except in the cases and according to the forms prescribed by law.

VI. The law shall provide for such punishments only as are strictly and obviously necessary, and no one shall suffer punishment except it be legally inflicted in virtue of a law passed and promulgated before the commission of the offense.

VII. As all persons are held innocent until they shall have been declared guilty, if arrest shall be deemed indispensable, all harshness not essential to the securing of the prisoner's person shall be severely repressed by law.

VIII. The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write, and print with freedom. No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views.

IX. A society in which the observance of the law is not assured, nor the separation of powers defined, has no constitution at all.

X. Property being a sacred right, no one except a convicted traitor can be deprived of it, unless public necessity, legally constituted, explicitly demands it, and then only under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

---

Excerpted from The French Revolution and its Aftermath, by Robert Goulard (De Gas, France, 1967):

The Declaration of the Rights of Humanity was completed and adopted several weeks before the proposed consitution was finished. Having seen the Declaration, Caritat moved to adopt it into the constitution, forming the first ten articles, and thus becoming legally binding. On the 11th of October, his committee presented their consitutional draft. In explaining the principles and motives behind the constitutional scheme to the Assembly, Caritat approached the issue very much like the mathematician he was at heart, by presenting the whole thing as a problem to be solved:

“To give to a territory of twenty-seven thousand square leagues, inhabited by twenty-five million individuals, a constitution which, being founded on the principles of reason, liberty and justice, ensures to citizens the fullest enjoyment of their rights, and which adheres to the national identity of our nation; to combine the parts of this constitution, so that the sovereignty of each individual and of our people as a whole is assured; to create an equitable balance, so that the legal framework shall not hinder the exercise of natural liberty, but protect it—such is the problem that we had to solve.” [2]

The constitutional document introduced by the committee encompassed the following points:

- The French Republic would be a federal state, as advocated by Montesquieu, and based on the examples provided by Prussia and Poland. [3] The pre-existing provincial boundaries would mostly be maintained, and historical regional identities respected and enshrined: the new provincial assemblies were explicitly instructed to observe their local culture, customs and traditions.

- The provinces would be further divided into districts, and the districts into urban and rural municipalities. Property owning citizens of a municipality would have a direct vote in a town hall assembly. The town hall assembly would elect representatives to the district assembly, who would elect representatives to the provincial assembly, who would who would in turn elect representatives to the National Assembly of France. All assemblies were to be unicameral. At every level, one third of the seats would be vacated every two years, and filled again in new elections. Thus, the whole assembly would never be replaced at once. [4]

- Citizenship was to be granted to men and women of all races who were at least 21 years old, following an uninterrupted residence of one year on French soil, counting from the day of their inscription on the civic table of a municipality. The right to vote, as well as to be elected to public office, would be enjoyed by all property-owning citizens. [5]

- The legislative assemblies at all levels would have the authority to appoint a five-person directory, which would head the executive branch. The assembly would at all times retain the right to remove any or all of the directors, and replace them with others. The presidency of the directory would rotate on an annual basis.

- The national government would be charged with foreign affairs, the army, the navy, the National Guard, education and main infrastructure. In addition, certain matters of finance and economic policy would be dealt with at the national level. All other affairs would be handled at the provincial level, or could be delegated to district or municipal level.

- All citizens in a position to bear arms would constitute the military force of the French Republic. The national Directory would appoint generals via commission, for the time of a campaign, and only in the event of war. Citizens of the Provinces would elect the commanders of their National Guard divisions. The French Republic would only engage in warfare for the preservation of its liberty, the conservation of its territory and the defence of its allies. War could be only be decreed by the National Assembly.

- Considering the current state of chaos and unrest throughout France, the current National Assembly would remain in session until such time as orderly elections could be carried out, and would appoint a National Directory to see to it that order was restored as soon as possible.

---

Excerpted from The Trial of a King, by Fantine Baubiat (De Gas, France, 1972):

After some deliberation, the former royal family was transferred to the Bastille. Infamously used as a prison under his own regime, one of the first acts of the Provisional Executive under Riqueti had been to issue a number of decrees outlawing all lettres de cachet, as well as prohibiting the inhumane treatment of suspects and convicts in general. The Bastille was, as a result, no longer in use as a prison. Naturally, when the former king and his family moved in, conditions inside the fortress were vastly different from they way they had perviously been. There was no luxery, but it was made fit for human habitation. And there, the erstwhile king of France awaited his trial.

The Directory was partial to keeping Louis enprisoned, both as a hostage and as a bargaining chip. Some of the more radical members of the Assembly advocated the execution of “the tyrant,” but there seemed as yet to be no majority for that point of view. The Assembly did, however, demand a trial. It was finally voted upon, and the Assembly ruled that only the representatives themselves, invested with the responsibility to defend the right of the people, could have the authority to try the former king. And so, the deposed king was fetched from the Bastille to stand before the Assembly and hear his indictment: an accusation of high treason and crimes against the people of France. The former king was given adequate opportunity to respond to these charges, which he did, assisted by his legal council.

The verdict was a foregone conclusion: some two-thirds of the Assembly deemed Louis guilty, none deemed him innocent, and roughly a third of the representatives abstained from the vote. The very next day, the Assembly met again. This time to decide upon the punishment to fit the crimes. All members of the Directory argued against the death penalty, with Caritat famously arguing that executing the king would mean “accepting the unacceptable,” namely that violence was a legitimate tool to achieve one’s goals. He admonished the Assembly: “If we choose to accept that one person may be killed to serve a vast number of people, than it shall not be long before we accept that a few more people may also be killed to serve a vast number of people. Ever greater sacrifices will be found acceptable in the name of the greater good, and before long we will be sacrificing a vast number of people, and excusing ourselves for it by saying we are doing it to help a vast number of people.”

In the end, roughly 15% of the representatives voted to exile the former king, 40% voted to execute him, and 45% to let him live out his days as a prisoner. It was a relatively close thing, but leniency carried the day. This was a turning point in the chain of events we now call the French revolution: reason and rage had previously been competing forces within France. Had rage won out, who knows what would have become of the revolution? It is unlikely that Caritat must be taken at face value; it is unlikely that executing one man would have opened the doors to a republic of gallows, where mass executions became the norm… but surely we must be glad that France was never put to test so severely. When one considers the terrible events in Bavaria, one shudders to think that even a fraction of such bloodshed could have occurred in one’s own country.

The radical enragés certainly demonstrated a furious bloodlust during the deliberations, even though they were but a minority. After the sentencing, Director Riqueti made good use of the opportunity to warn the Assembly against the danger of mob rule. Although the cause of reason had triumphed that day, he wished to permanently forestall the rise of armed mobs, which would only drive the revolution further and further along a destructive path of violence. Opposing those who maintained that the “new citizen” should be forged in some revolutionary fire, he proposed that revolution was only a means to an end—namely to establish political rules and legal mechanisms that would ensure future changes could be implemented without revolution. In a free republic, there would be no more tyrants to revolt against. Universal education would foster free and responsible citizens, who could solve their problems without resorting to violence. The new constitution and the reasonable approach to justice that the Assembly had chosen were certainly steps in that direction, but while Riqueti’s oratory was compelling, many knew that reality was less tranquil. There was still a long way to go.

---

Excerpted from Economics, a History, by Augustin Cassat (De Gas, France, 1970):

As unofficial leader of the Physiocrats, Director Caritat was placed in charge of fiscal and economic policy. Like his fellow Directors, he quickly enlisted the help of talented secretaries to aid him in his tasks. Caritat’s chief secretary was Albert Gallatin, a Swiss-born economist of the Physiocratic school. Gallatin had originally intended to travel on to the United States in 1780, but had become involved in the Physiocratic Société Economique while in France. [6] He had decided to stay, and study under Caritat and other leading economists. His talents proved useful now, as he aided Caritat in preparing a fiscal and economic program for the French Republic.

Presenting the resulting plan to the Assembly, Caritat boldly announced as his objective: the final abolition of abusive privilege, and the subjection of all landowners to fair and reasonable taxation. He presented a vast and ambitious plan of tax reform, simplification of the complex administrative system and thorough economic liberalization in order to remedy the fiscal crisis. In the face of the nation’s desperate financial situation, he also advocated the enforcement of a rigid budget control in all departments of the government. All expenses were to be submitted for a priori approval. Ultimately, he introduced six major proposals before the Assembly:

1) Replace all existing taxes with a universal land tax, a subvention territoriale, to be levied on all property without distinctions.

2) No overall increase of taxation, no increase of the public debt.

3) Cut government spending and enforce strict budget control.

4) Foster a revival of free trade methods: abolish the grain laws and all of France’s myriad internal customs barriers and duties.

5) Introduce complete freedom of trade, commerce and industry; abolish the guild monopolies and guarantee the right of every citizen to work without restriction.

6) Approve the sale of Church property to benefit the treasury

A major point of the Physiocratic approach was, as it had always been, the introduction of the single tax on land. In Caritat’s final proposal, based directly on Turgot’s plans, the tax would be administered and collected at municipal level. The municipality would then keep 25% of revenue, while the district received 75%. Of which it would then pass on two-thirds to the provincial administration, which would send half of that to the national government. Thus, each level of government would receive one quarter of tax revenues. The implementation of the new tax system, along with the other drastic reforms, could stabilize France and allow for further modernization of the country.

First, however, France would have to be brought to order. Various regions were still under monarchist control, and the remaining supporters of king Louis were organizing themselves in a “Catholic and Royal Army,” which sought to restore the old regime. Meanwhile, many of the crowned heads of Europe had turned a wary gaze upon France, witnessing the establishment of the Republic with concern and outrage. They considered intervention, be it to assist the deposed and imprisoned king Louis or be it to take advantage of the internal unrest in France, but at first remained undecided on the issue. That would soon change.

---

Excerpted from The Enlightenment in Europe: Philosophy and Politics, by Marcel Musson (Agodi Books, France, 1963):

As the monarchs of Europe struggled to find an adequate response to the French revolution, Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II was a crucial figure in determining what that response would ultimately be. Joseph was the older brother of Marie Antoinette, who was in turned married to Louis, the son of king Louis XVI, and dauphin of France. [7] Initially, Joseph had looked on the revolution with ambivalent feelings, hoping it would result in Louis XVI abdicating in favor of his son. That would result in some much-needed reforms, and at the same time tie the French monarchy closer to Austria. When the revolution in France became explicitly republican, however, Joseph turned decicively against it. He let it be known that the abolition of the monarchy was a transgression against the natural order of things, and that Austria would support the attempts at a royal restoration. In spite of this, he still hoped to avoid war, and took no concrete steps to support the monarchist cause.

In early 1785, in consultation with emigrant French nobles, Joseph issued the Declaration of Schönbrunn. In it, he voiced the concern of the monarchs of Europe, their interest in the well-being of the former royal family, and issued the threat of unspecified but dramatic consequences if the former king or his family should be harmed. Furthermore, he again stated his dedication to restore the French monarchy, though he explicitly proposed the option of installing the dauphin—his brother-in-law—as a constitutional monarch. In addition to these statements, Joseph called upon the monarchs of Europe to unite in containing the revolutionary threat, stating that “while reform is much-needed and admirable, violent revolution is a sin against nature.”

Part of Joseph’s approach to contain revolutionary sentiments was to reconsider his own agenda of reforms within the Habsburg monarchy. Since the death of empress Maria Theresa in 1780, he had been free to embark on a new course. He had hastily begun an attempt to realize his own ideal of Enlightened despotism, without first preparing his empire for such reforms. He had abolished serfdom in 1781 without consulting the aristocracy, and sought to spread education, foster the secularization of church lands, and provide for a measure of religious tolerance. More importantly, he continuously strove to rationalize and unify the administration of his empire at all governmental levels. These policies were firmly rejected by the nobility, and though they were often in the interest of the people at large, they were not adequately explained and often ill-received. The risk of revolutionary resistance to his well-intentioned reforms gave him ample reason to stop and re-evaluate his policy.

By this point, however, his radical reforms had led to violent resistance in several parts of his empire. In same cases this resistance was instigated by progressives who supported his reform but rejected his autocratic ways, in other cases it came from conservative nobles who balked when the emperor curtailed their age-old priviliges. When Joseph announced a change in direction in 1785, the Hungarian aristocracy did not believe him, and the Austrian Netherlands were already in a state of insurrection. Joseph resolved to deal with Hungary first, restoring the aristocratic privileges in full. He believed that if he could get the aristyocracy back on his side, he could then formulate a strategy to deal with revolutionaries on the fringes of his empire. While he ultimately succeeded in regaining the support of the nobles, by that point the Batavian and French republics had already become involved in the Austrian Netherlands. The plan to contain the spread of revolution had failed before it had even been implemented.

---

---

Excerpted from The Batavian Revolution, by Bertold Wagenaar (Spieker Press, Batavian Republic, 1939):

As soon as the revolution swept through the Republic of the Netherlands, its influence also spread across the border into the Austrian Netherlands. As had long been the case in the Republic, the people of the southern Netherlands had of late been confronted with an autocratic ruler imposing his will on them without even a semblance of consultation. Emperor Joseph II no doubt meant well, but his drastic reforms, designed to radically modernize and centralize the political, judicial and administrative system, were imposed without even consulting the wealthy urban merchant class—who would otherwise have been highly receptive to such innovations. Most shocking was the emperor’s decree that the ancient provinces of Flanders, Brabant, Hainaut and Namur were immediately abolished, and replaced by 9 adminstrative circles, subdivided into 64 districts. German was subsequently imposed as the language of administration, despite the fact that the people spoke either Batavian Dutch or French.

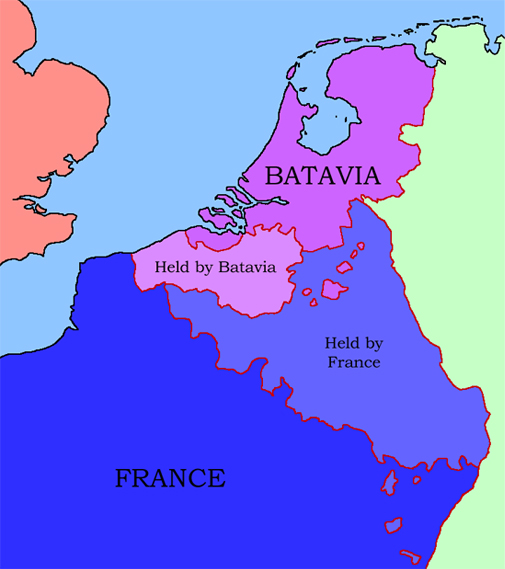

Conservative elites seeking to protect their legal and religious privileges now found themselves side by side with progressive reformers opposing the autocratic centralization forced upon the southern Netherlands. Their differences momentarily cast aside, the two factions joined forces, inspired by the succesful revolution in the Republic, directly to the north. The Catholic conservatives of the southern Netherlands had no issue with following that example: the Batavian revolution had thus far not resulted in expropriations of any kind, and had in fact guaranteed Catholics the right to worship freely. Then the French revolution broke out, and a panic arose at once. Would the French, decidedly more anti-religious than the Batvian Republic, try to seize the southern Netherlands? [8] Better to seek aid from the north at once! And so, in 1785, the reformer Jan Frans Vonck and the conservative Hendrik Van der Noot crossed the border into the Batavian Republic. By that point, many people in the southern Netherlands, and particularly in Flanders and Brabant, had already begun to identify as “Batavian,” following the example of their “northern kinsmen.” After all, did they not stem from the same tribes?

Vonck and Van der Noot found ample support in the Republic, and raised a considerable army of volunteers in Breda. In January 1786, this army marched south and was warmly received in Antwerp. Once there, Vonck issued a declaration that the emperor’s rule was no longer recognized, all acient privileges were guaranteed, and the southern Netherlands would enter into a confederation with the Batavian Republic. [9] This was rather hasty: many welcomed the security such an arrangement offered while still guaranteeing their sovereignty, but a considerable number of people (mostly in the Francophone provinces) did not identify themselves as “Batavian” at all. Minor protests erupted, major uncertainty abounded, and then the Danish invaded.

---

FOOTNOTES

[1] This is where the ramifications of TTL’s early death of Rousseau truly start to become obvious. IOTL, the entire French revolution was shaped by Rousseau’s ideas. In TTL’s revolution, his ideas are completely absent. Most crucially, there is no notion of a “general will,” to which the individual will should be subjugated. Instead, the ideas of the French revolution are more similar to those of the American revolution. That is to say: the value of individual freedom is held sacred, and instead of individual rights emanating from a “general will,” all government powers must be derived from the consent of the individual citizens. This, of course, completely butterflies away anything like the Jacobin Club—which was essentially the Rousseau Fanboy Association.

[2] Again, the absence of Rousseau’s influence is of great importance. No references to a “general will”. The main objective is to enshrine the rights of the individual. The far greater influence of Montesquieu also becomes obvious, particularly in regards to his ideas on the importance of cultural distinctiveness. IOTL, there was no reference to “the cultural distinctiveness of our nation.”

[3] No unitary state ITTL. Montesquieu’s influence again, plus the fact that decentralism and progressive/Enlightened ideas are closely associated ITTL.

[4] A far more conservative approach than the radical democracy that Republican France introduced IOTL. Again: no Rousseau, more of Montesquieu, plus the fact that there are less-radical reforms going on in several other countries, which influences the way the French choose to approach matters.

[5] Granting citizenship to women and non-whites was one of Caritat’s objectives. (Observe also that France adopts a Declaration of the Rights of Humanity, rather than the rights of Man.) Granting citizenship to everyone who lived in France for a year was a thing that happened IOTL. Restricting the right to vote to landowners is a Physiocratic notion: they want landowners to be the sole taxpayers, and by their logic, only those who actually pay taxes get to vote on how the money is spent.

[6] IOTL, he did travel on to the United States.

[7] OTL’s Louis XVI, obviously.

[8] Observe that although the French are more anti-religious than the Batavians, they are decidedly less radical on that front than they were IOTL.

[9] Interestingly, this is something that even Van der Noot, the conservative, desired IOTL. With the reformers and the conservatives working together at this point, and the Batavian Revolution having succeeded without too much fighting, a confederation of all the “Batavian Netherlands” suddenly becomes a realistic option.

GENERAL NOTES

Yes, those are a lot of footnotes. No, that closing line about the Danish invading is neither a typo nor a joke.

Last edited:

Wow, nice update! I'm glad to see that the French Revolution didn't devolve into wanton murder and terror like OTL, even if I think the Ancien Regime generally deserved it; there's something to be said for restraint and reason after all. Joseph II on the other hand can take a flying leap for all I care, his way needs to go. It's a good thing that the Austrian Netherlands decided to try joining with Batavia (I've always thought that should be the case IOTL as it is). But DENMARK?!

Wow, nice update! I'm glad to see that the French Revolution didn't devolve into wanton murder and terror like OTL, even if I think the Ancien Regime generally deserved it; there's something to be said for restraint and reason after all. Joseph II on the other hand can take a flying leap for all I care, his way needs to go. It's a good thing that the Austrian Netherlands decided to try joining with Batavia (I've always thought that should be the case IOTL as it is). But DENMARK?!

Yes. Denmark.

Do I even wanna ask about Denmark, or will we have to wait for the next update for clarification?

I honestly want to have more to talk about on the other stuff, but it just seems pretty evident how things are coming along. How do you think Austria will turn out before long, not just in terms of Franco-Batavian relations?

I honestly want to have more to talk about on the other stuff, but it just seems pretty evident how things are coming along. How do you think Austria will turn out before long, not just in terms of Franco-Batavian relations?

Do I even wanna ask about Denmark, or will we have to wait for the next update for clarification?

I honestly want to have more to talk about on the other stuff, but it just seems pretty evident how things are coming along. How do you think Austria will turn out before long, not just in terms of Franco-Batavian relations?

I promise an update on monday, and it will be clarified then. But I've really given a major hint in an earlier update, so the likely cause of the Danish incursion can be extrapolated.

Austria. Oh, Austria. Currently, not so very much is different. Well... some things are different (it'll be addressed in Part VIII), but politically speaking, Austria is generally following its OTL course. But things will change. For everyone.

By 1800, the map of Europe will be unrecognizable to the people living in 1786. These times were wild and furious IOTL, and they will be ITTL. But in a different way, with different players and different winners and losers.

In fact, every mapmaker in the western world is going to see a lot of business come the turn of the century. Oh yes. (It is at times like these that I deeply regret the fact that this forum does not provide a 'diabolical grin' smiley.)

Minor protests erupted, major uncertainty abounded, and then the Danish invaded.

Now that's a punch-line!

No, that closing line about the Danish invading is neither a typo nor a joke.

Whoa!

I have come back to this, and am even more impressed than by the earlier sections. Very well written, with near-immaculate editing. And clearly there's a lot of research here.

I was somewhat disappointed at the comparatively minor role of "Sans Souci" in the Revolutionary War.

Very interesting idea to have Dauphin Louis survive and succeed.

I promise an update on monday, and it will be clarified then. But I've really given a major hint in an earlier update, so the likely cause of the Danish incursion can be extrapolated.

Willliam's marriage to a Danish Princess...

I have come back to this, and am even more impressed than by the earlier sections. Very well written, with near-immaculate editing. And clearly there's a lot of research here.

Wow, thank you! I'm really glad you like it, and I'm particularly delighted to hear that my writing seems to be improving.

I was somewhat disappointed at the comparatively minor role of "Sans Souci" in the Revolutionary War.

I'll consider that for the rewrite that will lead to the finalized version that I'll eventually post when it's all done. I can see how his relatively minor role would seem a bit of a let-down. Possible option: having Washington refuse the Consulate, but Sanssouci serve one term, instead of Franklin's second term (after having Franklin retire earlier).

I'm open to suggestions.

Very interesting idea to have Dauphin Louis survive and succeed.

You have a unique definition of "succeed," I must say.

Willliam's marriage to a Danish Princess...

That's right. So let's find out what's rotten in the state of Denmark, in the final installment of Part VI:

---

Excerpted from The Danish Incursion of 1786, by Ronald Smit (Vuurvliegh, Batavian Republic, 1958):

From the moment stadtholder William V and his family arrived in Kobenhaven, he attempted to gain support for an expedition to reclaim “his” country. The prospect only excited some minor enthousiasm at the Danish court, and the exiled stadtholder grew increasingly desperate over the years. In an attempt to enlist Danish support, and no doubt encouraged by his wife, a Danish princess, William eventually resorted to a strategy where he would buy the assistance he needed. He promised wealth and lands to those who would support him in a succesful bid to retake the Batavian Netherlands. Moreover, he approached the power behind the throne: Juliana Maria of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, who had been regent in all but name since her stepson king Christian VII of Denmark had gone insane in 1770. William appealed to the intensely conservative and nationalist Juliana Maria by vowing to enter the Netherlands into a solemn league with Denmark if he retook the country. In such an arrangement, Denmark would then be the senior partner.

Although an expedition was eventually arranged, Juliana Maria was cast aside in 1784 when prince Frederick, the son of Christian VII, reached adulthood and claimed the regency for himself. Frederick was a liberal, not particularly inclined to sympathize with William’s plight. But on the other hand, such an endeavour would certainly mean that he would curry favor with the nationalist faction, whose support he lacked. This led the young prince-regent Christian to give his blessing to William’s expedition, and a modest Danish fleet, in conjunction with mercenary auxiliaries, headed for the Batavian Republic in early 1786. The aim was to take advantage of the fact that the Republic was distracted by its own attempts to unite with the southern Netherlands, and this plan largely succeeded. That, however, did not mean that the battle was won. After some initial victories upon landing in Zeeland, William and his Danish confederates encountered unexpectedly fierce resistance, and were forced to admit that the republicans of Batavia were dedicated to maintaining their new system.

William had expected—and had promised his Danish soldiers—that the vast majority of the people would flock to his banner. Instead, they rallied around the flag of the Republic. Still, he had taken the republicans by surprise, and persevered in his attempt to regain power. He might even have succeeded, had it not been for the simple fact that the French decided to come to the aid of their sister republic.

---

Excerpted from The French Revolution and its Aftermath, by Robert Goulard (De Gas, France, 1967):

From the outset, French revolutionary ideals contained a powerful missionary strain: liberty was a universal right, and many felt it should be exported far beyond the borders of France. The Directory was understandably cautious, but following emperor Joseph II’s publication of the Schönbrunn Declaration, public opinion in France swung behind the more radical faction advocating the proselytization of freedom, republicanism and individual rights. The most prominent supporter of this approach was journalist-philosopher Jacques Brissot, also a highly active member of the National Assembly, who proclaimed that emperor Joseph, previously a supporter of radical reform, “must surely have lost his mind.” In an open letter to the emperor, Brissot reacted to both the Declaration and Joseph’s autocratic way of dealing with issues. He passionately argued that all peoples had a right to revolt against the misrule of a monarch, and that the Batavians of the Austrian Netherlands were simply exercising that right. Brissot won great acclaim, and the Assembly soon elected him to be its president.

In that capacity, Brissot delivered several inflammatory speeches, encouraging his countrymen to spead liberty across the map of Europe. Meanwhile, progressives in Nice, Savoy and the Rhineland requested annexation by the French Republic, as did a delegation from Hainout in the Austrian Netherlands. The Directory hesitated to move forward with such drastic steps, but Brissot declared that France would only rest when all of Europe could bask in the lights of liberty. And besides that; he also felt that France should expand to meet its “natural borders.” Brissot and his allies expected that annexed territory could provide new revenue, and thus aid in solving the economic crisis.

Then, in february 1786, the deposed stadtholder William V invaded the Batavian Republic with Danish assistance. This was precisely the casus belli that Brissot needed. He convinced the Assembly that France had a sacred duty to aid her sister republic, and that Joseph II would surely exploit the situation to subjegate the Austrian Netherlands—and then France! The only way to avoid such a scenario would be to pre-empt it altogether. To assemble an army, liberate the Batavians, march to the Rhine, and give France secure borders. Brissot rallied the support of the Assembly, and on the first of March 1786, France declared war on the Holy Roman Empire.

Brissot’s proposals, and the declaration of war, were eagerly supported by general Charles-François Dumouriez, who had been born in Cambrai. Six years before his birth, Cambrai had still been a part of the Walloon region of the Netherlands, and Dumouriez would always consider himself a Walloon. He was dedicated to the cause of an independent Republic of the Netherlands, allied to France. The Directory duly appointed Dumouriez to become involved in the mission of liberating Batavia. Dumouriez subsequently planned the invasion, stessing the importance of good logistics, and rejecting the proposal that French armies should be allowed to loot in the territory they had won. He realized that lack of supplies would be fatal, and that rampant looting would mean that any plan concerning Batavia would fail due to a lack of popular support among the Batavians. [1] These observations proved crucial to the success of the entire expedition.

---

Brissot and Dumouriez, two of the most fervent advocates of exporting the revolution to other countries.

---

Excerpted from A History of Warfare, by A.J. Steinhower (Rockwell Books, Confederacy of Southern America, 1941):

Having prepared a sound strategy, the armies of the French Republic marched to the aid of France’s fellow revolutionaries in other nations. In truth, however, the revolution had thoroughly disorganised the army, and the forces raised were barely sufficient for the planned invasion. The armies marching north soon encountered Austrian forces: emperor Joseph and his government had finally decided that revolutionary activism would have to be crushed by force of arms. The emperor had requested that king Henry of Prussia join in suppressing the revolutionary movements in France and elsewhere, but Henry had not believed this to be in Prussia’s interest. This is surely what saved the French armies from annihilation.

Despite both sides being evenly matched numerically, the French were soundly defeated by the Austrians in the first two engagements near the Rhine. Many French soldiers, largely untrained and completely untested, fled at the first sign of battle, deserting en masse. France’s enemies assumed the offensive. While the Directory scrambled to raise fresh troops and reorganise the French forces, an Austrian army moved to capture the fortresses of Longwy and Verdun. Dumouriez acted promptly. Diverting from his objective—the Batavian Republic—he swung east instead, adding the remnants of defeated French armies to his own forces, and facing the Austrians head on. In a crucial engagement at Verdun, he managed to surprise and crush the Austrian forces.

Combined with an arrogant manifesto issued by exiled French aristocrats—announcing their intent to restore the king to his full powers and to treat any person or town who opposed them as rebels to be condemned to death by martial law—this turn of events had the effect of strengthening the resolve of the French army. Dumouriez reorganized the armies in the north and ensured that logistics were sound. Leaving capable men in charge of the reorganized army heading for the Rhine, Dumouriez continued on to the southern Netherlands, where he severely defeated the Austrians near Brussels. After these military victories, he was ready to launch a further invasion of the Batavian Republic, and thus safeguard it against both the Austrian and the Danish threats.

Working together with Batavian forces, Dumouriez soundly defeated the Danish invaders—who had not anticipated having to face a French army—within a matter of months. Dumouriez’ aide-de-camp, Jacques MacDonald, distinguished himself during the campaign, and Dumouriez recommended the young man for rapid promotion. As soon as former stadtholder William V was captured and imprisoned, Dumouriez headed south again. The Republic proper now secure, his main objective became to safeguard Flanders and Brabant against Austrian forces. From there, he went east, aiming to occupy Luxembourg.

Meanwhile, the French had been successful on several other fronts, occupying Savoy and Nice, while the armies Dumouriez had sent east, under the command of François Christophe Kellermann and Adam Philippe de Custine, secured the left bank of the Rhine after driving the Austrians back across that mighty river. Within France itself, an army under general Jean-Baptiste de Vimeur (formerly the count of Rochambeau, and the man who had led the French forces in the American Revolutionary War) was hunting down the insurgents of the Catholic and Royal Army, aided by the National Guard under general Duportail.

When, by October, the Directory offered a full amnesty to all monarchist insurgents who surrendered within the month, many of the common soldiers accepted the offer. [2] They were rapidly losing motivation, and winter was coming. Contrarily, the soldiers of the French Republic had the advantage of being highly motivated by revolutionary zeal. In addition, Dumouriez—working together with Duportail’s National Guard—had ensured that French logistics were in good working order. By late 1786, the monarchist insurgency had been reduced to a handful of hotbeds, and France had for the better part expanded to meet its “natural borders”—while foreign invaders had been driven back across those borders. For a moment, it seemed that the troubles were over. But then Spain, Portugal and Great-Britain announced that they would enter into an alliance with Austria to subdue the clearly expansionist French Republic. The Alliance issued an ultimatum: France was to withdraw from all occupied territories and accept the dauphin Louis as a constitutional monarch. The National Assembly unanimously voted to reject the ultimatum, and thus commenced the era of the Patriotic Wars.

---

The situation west of the Rhine at the close of 1786

---

END OF PART SIX

---

FOOTNOTES

[1] IOTL, Dumouriez made these same observations, was ignored, turned out to have been right, and was nearly guillotined for his trouble. He eventually defected to save his life.

[2] One must keep in mind that TTL’s Louis XVI was, by the time of the revolution, far more widely despised than OTL’s king Louis XVI. The monarchist movement naturally attracts conservative aristocrats, but has far less support among the common people than it did IOTL.

GENERAL NOTES

This concludes Part VI. We are hardly done with Europe, though. Next up; a look at what's been happening in Britain during the turbulent time of the American, Batavian and French revolutions, in the seventh part of this timeline:

The Twilight of the Whigs

In addition to today's update, I have made a slight retcon. When talking about the Polish reforms, I initially stated that king Stanisław's natural son, Michał Cichocki, would be legally recognized as heir to the throne. It has been pointed out to me that such a development would be unlikely to the point of absurdity, since the king actually had a brother, who in turn has a son of his own.

So, instead of Michał Cichocki being legitimized, the king’s brother Kazimierz is legally recognized as heir to the throne, with Kazimierz’s son (also named Stanisław, like his uncle the king) becoming second in line.

The post dealing with this has been edited accordingly.

So, instead of Michał Cichocki being legitimized, the king’s brother Kazimierz is legally recognized as heir to the throne, with Kazimierz’s son (also named Stanisław, like his uncle the king) becoming second in line.

The post dealing with this has been edited accordingly.

Share: