All right, it's been far too long, so before we start, a bit of a warmup from my sojourns on YouTube trying to recreate that Pure Moods CD from the '90s:

And with that:

---

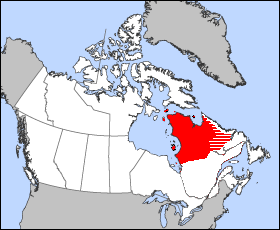

Source: The Maritime History Project at Memorial University, via Wikimedia Commons

Section 3: The Fishermen’s Protective Union

No description of pre-Great War Newfoundland would be complete without mention of one of the major political organizations in the outports. While the Fishermen’s Protective Union (FPU) may not have been directly successful in obtaining its goals, such was its importance that the FPU’s reform agenda became the Colonial Building’s policy during the 1920s. Even today, the effects of the FPU can be seen all over the Island and even as far afield as both Labrador and Ungava, and living daily reminders still exist in the form of the community of Port Union, located on Trinity Bay [1], and in the continuing work of the FPU today and in the University of Corner Brook. Its activities and history, alone, could fill an entire volume, as it was unlike other unions taking shape during this period. What follows is only a necessarily brief summary.

The banking crisis of 1894 had a devastating effect on the outports. Many fishing communities were dependent on a single merchant – often from St. John’s, though occasionally (and historically) from away – and the terms they dictated often determined the economic health of the country. It was the merchant who advanced credit to fishers in exchange for the seasonal catch. Prized among these was codfish, which could attract large markets. Yet during the late 19th century, the owners of the St. John’s merchant firms began reducing their investment in the fisheries. Stronger competition from overseas meant less incentive to focus on quality, while conservation measures – no matter how half-hearted and how often the merchants got around them – restricted the usage of certain types of equipment and what species of fish could be caught. This resulted in Newfoundland’s fish products earning a poor reputation, which restricted where it could be sold. More importantly for fishing families, the merchants also restricted the availability of credit – combined with the huge debt many families took on, poverty became widespread throughout The Rock, although it was partially offset by the winter and early spring Labrador seal hunt.

The end result was that the banking crisis threw rural Newfoundland into huge turmoil. Without access to banks, the merchants could not advance any more credit to families and were thus forced to reduce their operations. Indeed, many merchants went bankrupt, leaving whatever credit they advanced as useless. The Economic War exacerbated problems considerably, as the Whiteway Government found it difficult, if not impossible, to obtain the necessary finances to reopen the banks – at least not if Newfoundland could, and did, avoid joining Confederation. Despite the favourable coverage of Newfoundland in the American press, neither Washington nor Wall Street wanted to get involved with a basket case, as they viewed it. Furthermore, after the Economic War ended, the Bond Government preferred to focus on other priorities which potentially could strengthen Newfoundland’s position within the UK. This forced Newfoundlanders to turn to alternative solutions for survival. Those who lost access to credit – or did not have any credit to begin with – worked for those who did, which created a consolidation of merchant firms. Others turned to the towns, particularly St. John’s, where limited industrial output was taking shape as a result of the Government’s policy for industrial development as a vehicle of national survival, or took to the new timber camps.

Some scholars have compared the rise of the FPU to similar movements on the Mainland, in particular the United Farmers movement in Canada or the Populist Party in the United States. The comparison with the United Farmers movement in particular seems particularly apt, since – although under different circumstances – both had similar origins and goals. Both grew out of frustrations with dependence on merchant firms who had little idea of what was happening in agricultural communities. Both not only promoted the interests of their constituencies, but also were active promoters within rural communities of the co-operative movement. Although the FPU was neither as radical as the United Farmers nor did it ever form a Government, both also were engaged in politics and eventually were able to influence government policy towards their constituencies. Perhaps more telling of their continuing influence, once the FPU and United Farmers eventually got out of politics, they found a new lease on life (particularly the United Farmers of Alberta) as commercial groups, although retaining their co-operative ethos.

What made the FPU special was its radical departure from other fraternal organizations in 19th century Newfoundland. At the time of the FPU’s formation, most fraternal service organizations were organized on denominational lines, such as the Orange Order, the Star of the Sea Association (which was affiliated with the Catholic Church), and the Benevolent Irish Society. The FPU, on the other hand, had a membership which represented all denominations [2] and ignored distinctions based on merchant “loyalty”. Although the FPU’s main stronghold was in the northeastern areas of the territory, particularly Trinity Bay, in the conditions of the Economic War the FPU was able to represent most of rural Newfoundland and Labrador who were involved in either the fishery and/or the seal hunt. Part of its appeal was its community-based focus on improving the horrendous working conditions of the fishery [3] in reflection of how Newfoundland operated on family and community lines when it came to the merchants. Yet lest anyone had any ideas, from the beginning the FPU made clear that it disapproved of class warfare and looked at socialism with disdain. From a Catholic viewpoint, the FPU’s aims and goals could potentially help realize what Pope Leo XIII in his encyclical

Rerum Novarum outlined back in 1891, and this sense of social justice was attracted Catholics to the FPU and also overcame initial opposition from the clergy.

There wasn’t much time to lose when the FPU began operations, as the Economic War had ruined Newfoundland’s economy and impeded any chance of recovery in the fisheries, resulting in persistently poor catches – compounded by continued political neglect if not outright hostility. Its political focus had not yet crystallized when among the first priorities of the new Union was finding a way towards financial security for the outport communities. In fact, the direct origins of the FPU lay in its provision of financial services, paralleling the beginnings of the Desjardins credit-union movement in neighbouring Québec – with one big difference. [4] Originally, the FPU’s branches were places where fishers could exchange merchant credit for vouchers similar to early labour voucher experiments in the 1830s in Britain. As the truck system was gradually abolished and more Newfoundlanders were paid actual wages, the vouchers evolved into the beginnings of a federation of credit unions. For rural people, the FPU was their first experience in banking and in particular conducting services without the middlemen that were the merchant’s agents. The FPU soon quickly expanded with the foundation of the Fishermen’s Union Trading Company (UTC), which in reality acted much like a complement to similar retail operations and the health care work run by the International Grenfell Association (IGA) in Labrador and northern Newfoundland. At a UTC store, fishers could purchase their supplies at lower prices than the inflated prices by the merchants’ agents, and the UTC also acted as a cooperative substitute agent and joint marketing body for its members. As an extension of the efforts towards teaching financial literacy to its members, informal “study clubs” were formed, forming the beginnings of a parallel educational system to the denominational schools; these clubs quickly took towards discussing their current situation and identify solutions.

From these study clubs came the idea that there were two ways to effect real change in the lives of fishers. One was to take direct political action, which the FPU did in 1908 with the formation of the Union Party – an important step considering the poor 1907-8 fishing season. However, members also realized that it was just as important to take direct action within the outports and politics was not simply enough. So community co-operatives were established as a response to solving local problems. The FPU launched a newspaper, the

Fisherman’s Advocate, and even began operations of its own electric utility and shipyard. Concerned at the lack of schools in the region – and at the bad state of existing ones – the study clubs soon took the initiative and created their own free schools independent of the denominational system. These schools offered daytime education for children and night classes for adults and for children who had to work in the fisheries. On the Port au Port Peninsula, the local FPU study clubs pooled together money to invite teachers – primarily from France, but also from Canada – to teach local schoolchildren the French language, the Catholic faith, and assorted other subjects as an alternative to the existing Church-run schools based on those it ran in Ireland. [5] These Francophone teachers also taught adults how to read and write in their own native language, as well as the basics of English for interacting with the rest of the Island. Eventually, the idea came to pool money together to form a college to train future leaders of the FPU and to identify best practices in fishery management. The public land-grant colleges in the United States as well as the existing agricultural colleges in Québec would inspire this new college. In the meantime, FPU leadership would run an intensive training course for new members on co-operative principles, maths, accounting, economics, and public speaking.

The FPU’s political wing was based on the experiences gained from the various efforts made to improve the lot of outport residents, as well as the lessons learned from the study clubs. However, in the context of Newfoundland politics, the Union Party programme was radical. It wanted an end to the denominational system and locally controlled school boards, and by extension an end to all remaining vestiges of sectarianism, such as the road boards (which in effect, by that point, were similar to the poor law unions in the rest of Britain). It also wanted better fishery management, including an independent quality inspection process free of merchant influence. The Party also asked for an improvement in working conditions, such as pension reform and a minimum wage. It wanted reform to the conservation laws and the electoral system. Finally, it also advocated rural electrification. To demonstrate how such policies could work in practice, the FPU built its own town, Port Union – which also served as the Union’s headquarters. Although its policies were popular among the electorate, the structure of the House of Assembly was such that with the addition of the Union Party no one party could command a majority without forming a coalition Government. Sir Robert Bond initially refused to form such an alliance, until a string of Liberal by-election defeats finally convinced him to enter into an alliance with the FPU. The FPU rank and file, however, were disappointed when much of the legislation pertaining to their interests was half-hearted in trying to stake out a middle ground between the merchants and the Union. The FPU’s members, however, saw great hope in the formation of the county councils, and with elections to these august institutions the Union Party became significant players in local government and more successful in implementing their agenda (albeit without much success in ending denominational education). Meanwhile, the disappointments in improving the lot of ordinary Newfoundlanders led to the defeat of the Bond Government at a general election in 1913, exacerbated by a split several years earlier in the Liberal Party led by Bond’s own Attorney-General, Patrick Morris, forming the People’s Party. The People’s Party was his own political vehicle towards power, yet had a few problems of its own. It tried to mimic the FPU in its goals and priorities, but ended up splitting the Union Party vote in the Avalon Peninsula and the South Coast. Furthermore, although the People’s Party was officially a non-sectarian party, its vote share was largely sectarian in that it lured much of the Catholic vote.

From its beginnings in the Economic War, the FPU had grown significantly to the point where it became an authentic voice of the Newfoundland of the outports. It had taken the Government to task over clauses in the Government of Newfoundland Act, 1898, which required St. John’s to take full responsibility over its territory and thus pay attention to the needs of rural Newfoundland. At the same time, the FPU, though its many services, retained the support of many Islanders, despite public disapproval from the St. John’s fish merchants and – at first – even opposition from the Catholic Church. Yet its efforts to significantly improve the lot of their members at a national level ultimately proved futile, due to the reluctance of the Bond Government. For Sir Robert Bond, much like Sir William Whiteway before him, still believed that industrial development and not the fisheries was the key to Newfoundland’s future. The Great War delayed any chance of improving the economy or reforming any of the Bond Government’s legislation. After the War, a further split in the People’s Party led to that faction to merge with the Union Party and remaining Conservatives, along with some dissident Liberals, and form the Reform Party. [6] It would be the Reform Party that would fully implement the Union’s agenda, and thus transform Newfoundland in the process, alongside its traditional conservative focus.

---

OOC Notes

[1] Certainly better than the more interesting discovery of a nearly intact giant squid in the 1870s, which legend has it inspired the popular description of Captain Nemo’s enemy in Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea – and potentially served as an inspiration for H.P. Lovecraft’s creation of Cthulhu.

[2] In the case of Newfoundland, this is important. In OTL, because the FPU was overwhelmingly Protestant, it was distrusted by Catholics and was often accused of being linked with the Orange Order. In TTL, despite partially basing its organization along the lines of the existing denominational organizations for lack of alternate models (the Orange Order in the case of heavily Protestant areas and the Star of the Sea Association in the case of heavily Catholic areas) the FPU is extending the denominational compromise to bettering the lives of rural Newfoundlanders and Labradorians.

[3] This represents a fundamental departure from the original FPU in OTL. In OTL, William Coaker – one of the founders of the FPU – gave the FPU a more individualist self-improvement ethos. Because of the continuing Economic War in TTL, combined with an OTL banking crisis made worse in TTL which severely affected every facet of life in the outports, a more community-oriented focus is needed.

[4] This is a major departure from OTL, where William Coaker and the Union came first, followed by the trading operations – as far as I can tell, the FPU never really got involved in financial matters. In light of TTL conditions during the Economic War, however, the FPU has to create its own bank – or (if you prefer), in this case, its own credit union/building society hybrid. As can be seen, the FPU in TTL is a combination of the OTL FPU in Newfoundland and the later Antigonish Movement in Nova Scotia.

[5] This, of course, would lead in TTL to a different evolution of the French language in Newfoundland. In OTL, Acadian French co-existed with a nascent Newfoundland dialect that only really emerged in the 19th century as an offshoot of the dialect in St. Pierre and Miquelon, both of which largely evolved without any influence from a literary standard. Saint Pierre and Miquelon French, in turn, is similar to regional varieties spoken in the North and West of France, primarily found in Normandy and Brittany (and, to a lesser degree, the Basque Country), as well as intermediate varieties based on Standard French. In TTL, this hybrid of French, Québécois, Acadian, and local influences would make for an interesting mix that would be worth studying – particularly the Québécois influences, as before WWII the prestige dialect of Canadian French was based on the speech of Québec City.

[6] In OTL, the Union Party merged instead with the Liberal Party, creating the awkwardly named Liberal Reform Party (from whence I took part of the name for TTL’s new conservative party) under Richard Squires. Unfortunately, Squires was less than honest about his intentions, and the Liberal Reform Party was basically a corrupt patronage machine.

---

And here we are!

The long-awaited next update to this TL, and one about an important part of Newfoundland history, given a twist for TTL purposes. Once again, a belated thank you to

@Brainbin for keeping everything in working order.

This will, more or less, conclude the pre-Great War arc for this section. The next 2 updates - if and when they come - will deal with Newfoundland and the Great War. After that, I'll have to take a break in order to catch up with a few other projects I'm working on, as well as getting some updates written down. All I know is that up next will be the 1920s and 1930s, and this is when the butterflies will start doing their work, more so than the gradual limited development, paralleling OTL as much as possible, which I've been doing so far. So after the Great War, while there may be some similarities in some areas, in other areas I hope to plan on making things seem a little more different than OTL. And that's as much as I can say without spilling too many beans.

In conclusion, thanks for reading and for sticking by this TL for all this time. As always, constructive criticism is always appreciated.