You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Extra Girl: For the first heaven and the first earth were passed away.

- Thread starter Dr. Waterhouse

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 109 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Supplemental Note on Contemporary Crime, New Amsterdam Supplemental Note, The Construction of the Elbe Underpass, 20th Century Supplemental on the History and Goverment of New Amsterdam The Life of Elector Alexander of Saxony, 1566-1567 The Life of Elector Alexander of Saxony, 1567-1571 The Life of Julius of Braunschweig, 1550-1571 Supplemental Note on the Contemporary German Imperial Monarchy The Life of the Elector Alexander of Saxony, 1569-1573StephenColbert27

Banned

I don't know what this will be, but the title and picture intrigue me, so consider me subscribed.

The Life of Elizabeth of England, England and Saxony, 1492-1550

Madeleine de la Tour by Jean Perreal, as Elizabeth of England, Electress of Saxony

Gelica Deal: Today we are here in the privy orchard of historic Richmond Palace west of London as part of the palace’s quincentennial celebration. For five hundred years, since Henry VII rebuilt the older medieval residence of Sheen to serve as his primary official home, Richmond has been indelibly linked to the English royal family.

Thus in our on-going series we are reviewing the lives of the various royalty whose lives have been attached to Richmond at one time or another. Today, we are pleased to be interviewing Jeanne McBride, whose new book on the Princess Elizabeth, the daughter of Henry VII and sister of Henry VIII, who would go on to become the Electress of Saxony and thus play a crucial role in the momentous religious conflicts in the Germany of the sixteenth century, has just been published, and is available by slate and print.

Jeanne: Actually at that point it was called the Holy Roman—

Gelica: Yes, cheers, thanks a lot. Now, would the Princess Elizabeth have spent her youth here?

Jeanne: Actually, the younger Tudor princes and princesses were given the use of Eltham Palace, which has been since the late eighteenth century the official home of the Princes and Princesses of Wales. Of course the princess would have visited on official occasions, and spent some substantial time here in the years—

Gelica: I fancy it must have been a happy childhood.

Jeanne: Not really. The Princess Elizabeth suffered a serious illness from which she almost died at the age of three. Then when she was ten, her beloved mother, Elizabeth of York, died.

Gelica: But deaths from the complications of childbirth must have been part and parcel of life back then, wasn’t it?

Jeanne: They were common, but that doesn’t mean loss wasn’t keenly felt. We think that each of the children of Henry VII were affected differently. We know from letters written later by Prince Henry he was very affected by his mother’s loss. And the same can be said for Elizabeth, who was a year younger than Henry. Records in the ledgers of Henry VII actually survive of payments to various noblewomen and ladies assigned to care for her around this time. Not just pay for time spent, but compensation for bites, kicks and scratches inflicted.

Gelica: She was a little hellion, then?

Jeanne: We would think of it more in terms of an emotionally troubled little girl, who had been close to her mother, coming to grips with her loss only with great difficulty.

Gelica: So what was the relationships like between Elizabeth and the other members of her family, then? Were they close as a result of her mother’s passing?

Jeanne: With respect to King Henry VII, Elizabeth was unmentioned in his will. Now he died just as she had been married off by proxy to Duke Johann of Saxony and was in fact on her way to Wittenberg, so perhaps there are reasons for this omission other than an emotional distance, but there is little contrary evidence of any closeness—

Gelica: And what of her siblings, including Henry VIII?

Jeanne: Well, asides from the infamous letter from Wittenberg wherein she made the accusations against Charles Brandon, there is actually very little correspondence between the king and Elizabeth over the thirty-eight years that followed when they were both alive, certainly less than between he and either of his other sisters. However, she did write her younger sister, Mary. Apparently they had a strong friendship from early childhood that continued on through all the various changes of both their lives.

Gelica: She was also close to Katherine of Aragon, was she not?

Jeanne: Why yes, in fact there is some evidence that Katherine became almost a kind of surrogate mother for the princess after the death of Elizabeth of York. And this is reflected in the frequent, though occasionally interrupted, correspondence between the two between Elizabeth’s departure for Saxony in 1509 and Katherine’s confinement after the annulment of her marriage to Henry. Moreover, as late as 1534 Elizabeth was still maneuvering for her son the Elector Friedrich IV to marry Katherine of Aragon’s daughter, the future Mary I, partly out of her sentimental attachment to Katherine.

Gelica: I can’t imagine Bloody Mary looking too kindly on a marriage proposal from the first family of German Lutheranism!

Jeanne: In truth, they didn’t look too kindly on it either. Elizabeth, first as duchess, wife of the heir to the electorate of Saxony, then as electress, and finally as the electress dowager, essentially ran her own foreign policy by letter in a matter not too different from other powerful mothers and maternal figures of the era, such as Louise of Savoy and Margaret of Austria. But whereas these other women had interests almost wholly identified with the male rulers they were connected with, Louise with Francois I and Margaret with Charles V, Elizabeth’s grand objective in all that she did was the unity of Europe under the Catholic Church.

Gelica: But that would have meant she was explicitly at odds with the policies of her husband and son?

Jeanne: She was.

Gelica: Well how did that work? It wasn’t as if consorts had unlimited job security in this era, Anne Boleyn and all that.

Jeanne: In the case of Elizabeth, that’s actually rather complicated. For the most part the early years of Elizabeth’s marriage to Johann was happy, though their relationship became strained as the conflict between Martin Luther and the Catholic Church intensified.

Gelica: She counselled Friedrich the Wise to hand Luther over, didn’t she?

Jeanne: Counselled, begged, demanded. Now during these same years she bore Duke Johann four children, three of whom survived. She had also become a substantial patron of the University of Wittenberg and the Elector’s foundation in her own right, essentially helping to finance Friedrich the Wise’s relic collection. She also made dazzling contributions to court life in electoral Saxony, attracting well-known artistic figures such as Pierre Alamire and a figure who would become closely associated with her son, Ulrich von Hutten. In short, there were substantial reasons other than her royal lineage that she simply could not be set aside.

Gelica: Would you say she was in love with Johann?

Jeanne: I think it’s fair to say that, given the tone of their surviving letters, yes. Up until when Luther burned the Papal Bull in Wittenberg. From that moment on, their relationship was much changed. I think it’s fair to say there was likely some kind of very difficult personal confrontation, and at that afterwards nothing else between them was the same. Of course none of this is recorded, nor would it be. We simply know that at the time the Papal Bull was burned she was in Wittenberg with the court, and a few months later when she is next mentioned in the records she is holed up at Wartburg, where she would stay until 1525 when she had to be moved because of the advance of the armies in the Peasants Revolt. And of course, there were no more children or pregnancies after that, though she was still not yet thirty.

Gelica: That must have led to some difficult circumstances with the children.

Jeanne: Well, there too the circumstances are different with each one. With the future Elector Friedrich IV, their separation produced something much like the close relationship that existed between her father and Margaret Beaufort. That the pain of this separation may have affected his ideas about religion has been subject to much speculation, of course. But no doubt she was the closest to him, which makes sense given that he was the oldest at the time she was sent away. Johann the Younger seems to have adjusted easily enough to her absence. And in the case of Katarina, the daughter ironically named after Katherine of Aragon, the breach was profound, to the point we actually know Katarina somehow profaned a rosary her mother had given her, likely in protest of her lingering obedience to Rome.

Gelica: And this is the same Katarina who married Henry Brandon?

Jeanne: Yes. Elizabeth finally got her English match, though not with a child of Henry VIII as she wanted but instead her hated enemy Charles Brandon. And the child she married into the Brandons was perhaps the most strenuously evangelically-minded of all her children. Nonetheless, it is often forgotten that through that marriage she is an ancestor of Henry IX and all English rulers since 1603, just as she is the German imperial family.

Gelica: So tell us some more about her relationship to the Holy Prince. Just how much influence could she have had on him, if she were still a Catholic and he a leader of the Reformation?

Jeanne: That too is a very knotty matter. In some cases some elements of the character he exhibited were the results of seeds she planted inadvertently. For example, one of the first recorded disagreements Elizabeth had with her husband Johann was over Spalatin’s tutorship of the young ducal prince. Spalatin was an influential advisor to both Friedrich the Wise and Johann the Steadfast during this period and was a crucial go-between between the court and Martin Luther. Even before his role in the break with Rome, Elizabeth hated him with a fiery passion, though. Apparently the core of the issue was a difference of opinion over the appropriate discipline for her son.

She agitated until she was able to bring in tutors of her choosing for the future Friedrich IV. One of these was the knight Ulrich von Hutten, which is its own issue, and he had his own influence over the future elector. But another was Andreas Karlstadt, a professor at the university who would ultimately become a leading exponent of his own brand of reformation teaching that was actually much more radical than Luther.

So unbeknownst to either Johann or Elizabeth, at the precise same time Karlstadt was developing his radical ideas, he was teaching the bible to the young prince. And whereas Spalatin had a somewhat difficult personality, and provoked the animosity of both Elizabeth and the prince, we know for a fact that the young Friedrich developed a powerful affection for Karlstadt.

Gelica: Hmm, interesting.

Jeanne: Well, it is, actually. Because not only did this directly influence the Holy Prince’s own religious views, it meant that later, when Karlstadt’s influence on the young Friedrich became known, and Luther, and Johann, and even Elizabeth, all concurred that he needed to be put to death to stop the spread of his dangerous ideas, that had an incredible effect on the young future elector. We have it on record that the young man, inconsolable, cried for the better part of two days and had to be prescribed a narcotic for fear he might hurt himself.

From that point on, no amount of doctrinal training would ever make the young Friedrich the starry-eyed pupil of his version of reform that Luther wanted. Nor could Friedrich be persuaded to use violence to enforce doctrinal uniformity on the people of Saxony, which represented of course a huge break with the prior tradition in the west with respect to the role of religion in society.

Gelica: So, one last question then. What did Elizabeth think of her eldest son’s exploits?

Jeanne: The Electress’s career from the Reformation on was a never-ending quest to bring together her two great passions, that of her love for the Church of Rome and her love for her son. In her mind, the two interests were one and the same. She wanted his salvation ardently, and could only imagine it within the framework of his restoration to the Church. Thus as early as the 1519 imperial election she was attempting to negotiate some kind of advancement for him in return for the surrender of Luther or later, the re-establishment of traditional Catholicism in Saxony. The schemes were never-ending, including in one remarkable episode during the marriage of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn an attempt to reconcile her son to the pope, have the pope officially declare the throne of England empty, and have the newly Catholicized Friedrich himself lead an invasion of England to install himself as the new king.

Gelica: That seems rather far-fetched, doesn’t it?

Jeanne: Well, young Friedrich thought so too. Which is why nothing came of it. And that was probably a good thing for the family then known as the Ernestine Wettins. Else it would have unduly complicated their later dealings with Henry VIII.

Gelica: That’s all well and good, but it doesn’t answer the question, does it? The Electress Elizabeth lived long enough to see the pivotal moments of her son’s career as a ruler. She knew he would never be reconciled to Rome, and knew that in fact he had done much to make permanent the breach between the Reformed and Catholic churches. So what did she think of this? Was there pride in her son’s exploits, or regret?

Jeanne: Well, this we know for a certainty. Repeatedly, in the last years of her life, she refers to herself in her letters as the saddest woman in Christendom. She loved her son, but there is no doubt that his victory was her defeat, and in fact as far as she was concerned, the loss of his immortal soul.

Gelica: We are almost out of time. Anything else about Elizabeth you would like to share?

Jeanne: One fact about her frequently neglected is that, despite the deep unhappiness of her latter marriage to the Elector Johann, she is the only child of Henry VII to have survived to adulthood who married just the once. Henry VIII’s exploits we do not need to recite here, nor do we need reminders of Margaret Tudor’s eventful romantic life after the death of James IV of Scotland, or the famous circumstances of Mary Tudor’s marriage to the Duke of Suffolk. But even when the Elector Friedrich IV considered negotiating a marriage for Elizabeth, both as part of the endless diplomatic maneuvering in sixteenth century central Europe, and to get her out of his hair, so to speak, she should could not be prevailed upon. As she put it, she gave her whole heart the once, and that was enough.

Gelica: Well that’s quite sweet, isn’t it? A lovely note to end on.

Jeanne: Didn’t you pay attention to what I’ve been saying? She was imprisoned—

Gelica: And next on Morning Report, new developments in the French synthtelligence scandal may bring down the New Girondin government—

Last edited:

Just happened upon this TL tonight, and I'm interested in this TL: when's the POD? (Also, is Gelica short for Angelica, by any means?)

Good start to the reboot, @Dr. Waterhouse. Hoping you keep some of the same format and detail of the last version of this timeline (the cooking part was good), but I like the different beginning...

In 1495, the Princess Elizabeth, daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, does not die of the wasting disease that in our timeline took her life. She grows up as the somewhat testy middle child. Henry VII, knowing Mary is the more attractive candidate on the royal marriage market, matches Elizabeth with Johann, duke of Saxony, younger brother and heir of the Elector Friedrich the Wise. In doing so he hopes to secure a role in deciding the next imperial election, and perhaps even an opening for the candidacy of his son the Prince of Wales. During the marriage negotiations, with English ambassadors at the Saxon court, Johann's son the prince Johann Friedrich, dies under mysterious circumstances. This necessitates a quick conclusion to the negotiations, as the Saxon court fears the succession crisis that would arise if the middle-aged brothers Friedrich and Johann die without lawful issue.

Last edited:

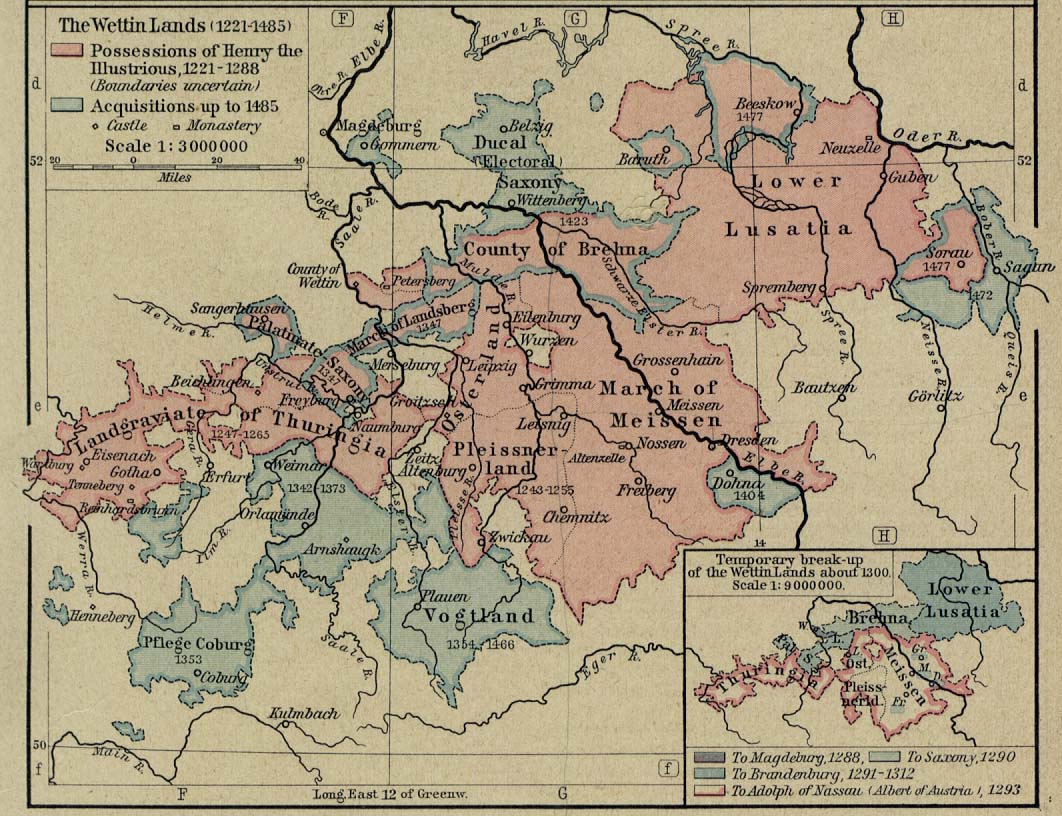

Prefatory Note I: The Rise of the Wettins to 1485

Prefatory Note I: The Rise of the House of Wettin

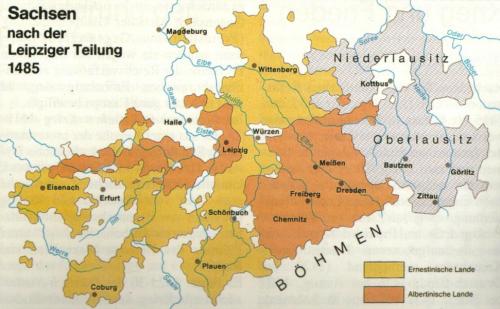

Prefatory Note II: The Partition of Leipzig

Prefatory Note II: The Partition of Leipzig

In 1485, the lands of the Wettins were divided between the brothers Ernst and Albrecht. Both of them were dukes. However, the electoral dignity, which is the right to cast a vote to elect a Holy Roman Emperor, passed to only the elder brother, Ernst. Thus the two sets of lands came to be known as Electoral, or Ernestine, Saxony, and Ducal, or Albertine, Saxony.

Ernst had three sons who survived to adulthood: his heir Friedrich, who would become the elector known to us as Friedrich the Wise; Ernst the younger, who would become Archbishop of Magdeburg and then Bishop of Halberstadt; and Johann, who would be Friedrich's heir as Johann the Steadfast. Ernst also had two daughters who survived to adulthood: Christina, who became Queen of Denmark, Norway, and, until 1501, Sweden; and Margarete, who became Duchess of Braunschweig-Lueneburg. Thus most of mainland Europe north of the Elbe was at the end of the fifteenth century either ruled by the Ernestine House of Wettin or had a consort of the house. At the same time, after his accession Friedrich III maintained a close relationship with Maximilian, King of the Romans and later Emperor, and assisted him in rule.

Albrecht also had three sons who survived to adulthood: his heir Georg, who would be duke of Saxony. Georg, descended on his mother's side from the Podebrady kings of Bohemia, in turn married a Jagiellonian Polish princess. Georg was succeeded by his younger brother Heinrich. Albrecht's third son, also Friedrich, became a grand master of the Teutonic Knights. A daughter who lived to adulthood, Katharina, was married first to the Habsburg Archduke Sigismund, and on his death to the duke of Braunschweig-Calenberg.

In 1485, the lands of the Wettins were divided between the brothers Ernst and Albrecht. Both of them were dukes. However, the electoral dignity, which is the right to cast a vote to elect a Holy Roman Emperor, passed to only the elder brother, Ernst. Thus the two sets of lands came to be known as Electoral, or Ernestine, Saxony, and Ducal, or Albertine, Saxony.

Ernst had three sons who survived to adulthood: his heir Friedrich, who would become the elector known to us as Friedrich the Wise; Ernst the younger, who would become Archbishop of Magdeburg and then Bishop of Halberstadt; and Johann, who would be Friedrich's heir as Johann the Steadfast. Ernst also had two daughters who survived to adulthood: Christina, who became Queen of Denmark, Norway, and, until 1501, Sweden; and Margarete, who became Duchess of Braunschweig-Lueneburg. Thus most of mainland Europe north of the Elbe was at the end of the fifteenth century either ruled by the Ernestine House of Wettin or had a consort of the house. At the same time, after his accession Friedrich III maintained a close relationship with Maximilian, King of the Romans and later Emperor, and assisted him in rule.

Albrecht also had three sons who survived to adulthood: his heir Georg, who would be duke of Saxony. Georg, descended on his mother's side from the Podebrady kings of Bohemia, in turn married a Jagiellonian Polish princess. Georg was succeeded by his younger brother Heinrich. Albrecht's third son, also Friedrich, became a grand master of the Teutonic Knights. A daughter who lived to adulthood, Katharina, was married first to the Habsburg Archduke Sigismund, and on his death to the duke of Braunschweig-Calenberg.

Last edited:

Like how you're setting up the background to this, @Dr. Waterhouse; it really fleshes out the TL...

Good to see Waterhouse brand Tudors back in action. (A little confused about the fat German prince thing)

Yeah, now as ever, sometimes my enthusiasm gets the better of me. A lot of that is detail from the novel. We're going to dispense with it for now. Edited.

Prefatory Note III: The Golden Bull and Imperial Elections

Prefatory Note III: The Golden Bull

From the Golden Bull of the Emperor Charles IV, issued by the Imperial Diets of Nuremberg and Metz, 1356 and 1357:

In the name of the holy and indivisible Trinity felicitously amen. Charles the Fourth, by favour of the divine mercy emperor of the Romans, always august, and king of Bohemia; as a perpetual memorial of this matter. Every kingdom divided against itself shall be desolated. For its princes have become the companions of thieves. Where fore God has mingled among them the spirit of dizziness that they may grope in midday as if in darkness; and He has removed their candlestick from out of His place, that they may be blind and leaders of the blind. And those who walk in darkness stumble; and the blind commit crimes in their hearts which come to pass in time of discord...

Something that should be stated first is that the Holy Roman Emperor was not merely the head of the empire. Rather, at least theoretically, he was like the pope an officer of all Christianity. We see this in small details, such as the fact that in the pre-Reformation English liturgical calendar congregations were obligated to pray for him on a given day. In one sense this affected the inchoate nature of the empire and its bounds: the emperor was both a lord to whom direct authority was given over some, and the first prince among Christians who was something of a worldly counterpart to the pope.

What the Golden Bull clarifies is the procedure by which Holy Roman Emperors are selected, which had been previously in controversy. One of the things that it does is to specifically deny the papacy a role in the election. Instead, it distributes the electoral dignity among seven specific princes of the empire, each of whom is given a specific ceremonial office. In actuality, the Golden Bull delves deep into ceremony and practice, prescribing even the placement of the princes when they meet. The King of Bohemia is given pride of place because he is himself an anointed king, though considering Charles IV was himself also King of Bohemia this should not be too surprising. While unanimity is sought and prized in imperial elections, they are necessary neither for the office of emperor or for the kingship of the Romans. A minority of the electors cannot block an election.

The Electors are:

Secular Princes

King of Bohemia Arch-cupbearer

Count Palatinate Arch-steward

Duke of Saxony Arch-marshall

Margrave of Brandenburg Arch-chamberlain

Ecclesiastical Princes

Archbishop of Mainz Arch-chancellor of Germany

Archbishop of Cologne Arch-chancellor of Italy

Archbishop of Trier Arch-chancellor of Burgundy

Because of the complex nature of the imperial office, election by itself is not sufficient to make the elected prince the emperor. That requires a coronation by the pope. In the case of Maximilian I, Pope Julius II agreed to let him use the title of "elected emperor" while foregoing the actual coronation. In the case of Charles V, he went from 1519 to 1530 elected, but not yet crowned, emperor.

Finally, it was intentional that the House of Habsburg did not receive an electoral dignity, because they were the rivals to Charles IV's reigning House of Luxembourg. Though Habsburgs were elected emperor, a Habsburg was not able to cast a vote in an imperial election under the terms of the Golden Bull until after Ferdinand became King of Bohemia in 1526. It was in reaction to this exclusion that, through the Privilegium Maius, the Habsburgs arrogated to themselves the title of archduke.

Last edited:

I'm assuming this is still OTL, of course...

Right. The purpose of the prefatory notes is to set the stage, so that way when we get into the action we're not both trying to figure out some obscure contextual details and follow the narrative at the same time. I think that was one of the things that made the first timeline so difficult to follow. Of course I'm being selective as to what I'm choosing to give this treatment. For example, I figure most of the ah.com audience who would be reading this knows the important branches of the Tudor family tree.

The Life of Elizabeth of England, Supplemental, 1520

from Elizabeth of England, Mother of Two Dynasties (1912) by George Jane

It well demonstrated that princess’ stature, that for the imperial election she accompanied her brother-in-law, with whom she was still on good terms for the most part, to Frankfurt. There, the diplomatists sent by her brother to secure for him the imperial crown did count on her to use her influence to support his election. Likewise, the elector and his courtiers did assume she would assist his purposes. Instead, in that matter so characteristic of her family the Duchess Elizabeth disappointed all but herself.

For she did not agitate on behalf of Henry VIII, for whom she had felt little warmth even when they dwelt under the same roof and shared a table, but instead the Habsburg. And though Frederick the Wise would otherwise have been happy to have her arguing, as he did, for the retention of the imperial crown by the House of Austria, he found bracing that she did so not because Charles could provide the surest defense against the Turks, or because he was a prince already of the empire rather than just a sovereign outside it, or even because he offered the most generous gratuity. No, instead the argument Elizabeth made was that it was Charles von Habsburg who might decide with a stern hand Germany’s fractious religious question, and bring to a speedy conclusion such “dangerous experiments” with heretical doctrine as she saw. Thus, in her intervention at Frankfurt the empire had its foretaste of the controversy that would engulf the princes subsequently assembled at Worms.

But of course the Ernestine Wettins, shocked that the chief woman of their house would so freely undermine their policy, began steadily to circumscribe Elizabeth of England’s contacts, both at their court with princes, ambassadors, heralds and the merchants and tradesmen with whom letters could be conveniently transmitted, and in the houses allocated Elizabeth by her 1509 marriage contract. Worse yet, Elizabeth found her contact with her children checked and limited by the discretion of brother-in-law and husband, and her power to make decisions with respect to their nurses, tutors and other servants curbed, all of which was due to the fear she might steer the Wettins’ heirs away from Luther, and into a renewed allegiance to the Church of Rome.

Much of this process by which the prerogatives and freedoms due the lady of a great house of the empire were stripped away is undocumented, given that her own marital insubordination constituted a grave scandal to the ruling family of Electoral Saxony. However, we know in no uncertain terms that the matter culminated the night Luther burned the Papal Bull in Wittenberg. No sooner did she hear of it did the Duchess go to her husband and reproved him before his court with all the haughty outrage she was capable of as a child of the House of Tudor. She announced henceforth the heresy of Luther could not be denied for what it was, that the Wettins were outside the Christian Church, and that she must take all steps possible to protect her own soul, and the souls of her children, no matter what else.

To this, Johann flatly said, still before assembled witnesses, that this impertinence could no longer be ignored. She risked with this bold and unnatural exertion being set aside.

Hearing such, Elizabeth laughed and said she would prefer to spend the remainder of her days in the meanest nunnery of Christendom and enjoy Paradise thereafter, than remain at a court now a sworn enemy to the Church that is the Bride of Christ.

Then, her husband countered, he would have to consider the terms of her appropriate confinement.

This too left Elizabeth un-cowed. Her rejoinder was that she would do well to be thus imprisoned, that in such confinements as he contemplated, both her lady grandmothers did vanquish their enemies and overturn kingdoms as surely as any general ever did upon a battlefield, that she would endeavor to do the same, and to make the restoration of her home and children to the laws of Christ her only pastime, and that she would not cease from her efforts to surmount whatever walls inside which she found herself, or to suborn her every gaoler, until either she was dead, or her goal won.

Flabbergasted, the duke replied she sounded like a woman who desired straiter imprisonment, rather than less.

And to that she made answer the wisest thing for him to do was to make her a martyr then and there, to at once rid himself of her and speed her soul to God. At hearing this, the whole court was abashed and even the duke, a stout and hardy man, seemed much amazed.

It was the next day she left, under close guard, and without her shield of redoubtable and most loyal ladies, for the castle of Wartburg, which had been previously assigned her in her marriage contract as part of her dower lands. It was only with tears and fearsome protests that her eldest son, the young Duke Friedrich, then a mere boy, could be pried off her as she was taken away, and some years later when she arrived at the same court, servants relating the story to Elizabeth Stuart said that at her leaving the young electoral prince wept blood.

It well demonstrated that princess’ stature, that for the imperial election she accompanied her brother-in-law, with whom she was still on good terms for the most part, to Frankfurt. There, the diplomatists sent by her brother to secure for him the imperial crown did count on her to use her influence to support his election. Likewise, the elector and his courtiers did assume she would assist his purposes. Instead, in that matter so characteristic of her family the Duchess Elizabeth disappointed all but herself.

For she did not agitate on behalf of Henry VIII, for whom she had felt little warmth even when they dwelt under the same roof and shared a table, but instead the Habsburg. And though Frederick the Wise would otherwise have been happy to have her arguing, as he did, for the retention of the imperial crown by the House of Austria, he found bracing that she did so not because Charles could provide the surest defense against the Turks, or because he was a prince already of the empire rather than just a sovereign outside it, or even because he offered the most generous gratuity. No, instead the argument Elizabeth made was that it was Charles von Habsburg who might decide with a stern hand Germany’s fractious religious question, and bring to a speedy conclusion such “dangerous experiments” with heretical doctrine as she saw. Thus, in her intervention at Frankfurt the empire had its foretaste of the controversy that would engulf the princes subsequently assembled at Worms.

But of course the Ernestine Wettins, shocked that the chief woman of their house would so freely undermine their policy, began steadily to circumscribe Elizabeth of England’s contacts, both at their court with princes, ambassadors, heralds and the merchants and tradesmen with whom letters could be conveniently transmitted, and in the houses allocated Elizabeth by her 1509 marriage contract. Worse yet, Elizabeth found her contact with her children checked and limited by the discretion of brother-in-law and husband, and her power to make decisions with respect to their nurses, tutors and other servants curbed, all of which was due to the fear she might steer the Wettins’ heirs away from Luther, and into a renewed allegiance to the Church of Rome.

Much of this process by which the prerogatives and freedoms due the lady of a great house of the empire were stripped away is undocumented, given that her own marital insubordination constituted a grave scandal to the ruling family of Electoral Saxony. However, we know in no uncertain terms that the matter culminated the night Luther burned the Papal Bull in Wittenberg. No sooner did she hear of it did the Duchess go to her husband and reproved him before his court with all the haughty outrage she was capable of as a child of the House of Tudor. She announced henceforth the heresy of Luther could not be denied for what it was, that the Wettins were outside the Christian Church, and that she must take all steps possible to protect her own soul, and the souls of her children, no matter what else.

To this, Johann flatly said, still before assembled witnesses, that this impertinence could no longer be ignored. She risked with this bold and unnatural exertion being set aside.

Hearing such, Elizabeth laughed and said she would prefer to spend the remainder of her days in the meanest nunnery of Christendom and enjoy Paradise thereafter, than remain at a court now a sworn enemy to the Church that is the Bride of Christ.

Then, her husband countered, he would have to consider the terms of her appropriate confinement.

This too left Elizabeth un-cowed. Her rejoinder was that she would do well to be thus imprisoned, that in such confinements as he contemplated, both her lady grandmothers did vanquish their enemies and overturn kingdoms as surely as any general ever did upon a battlefield, that she would endeavor to do the same, and to make the restoration of her home and children to the laws of Christ her only pastime, and that she would not cease from her efforts to surmount whatever walls inside which she found herself, or to suborn her every gaoler, until either she was dead, or her goal won.

Flabbergasted, the duke replied she sounded like a woman who desired straiter imprisonment, rather than less.

And to that she made answer the wisest thing for him to do was to make her a martyr then and there, to at once rid himself of her and speed her soul to God. At hearing this, the whole court was abashed and even the duke, a stout and hardy man, seemed much amazed.

It was the next day she left, under close guard, and without her shield of redoubtable and most loyal ladies, for the castle of Wartburg, which had been previously assigned her in her marriage contract as part of her dower lands. It was only with tears and fearsome protests that her eldest son, the young Duke Friedrich, then a mere boy, could be pried off her as she was taken away, and some years later when she arrived at the same court, servants relating the story to Elizabeth Stuart said that at her leaving the young electoral prince wept blood.

Last edited:

The Life of the Elector Friedrich IV, Saxony, 1527-32

From The Habsburg Struggle for Europe (1940) by Perez Wolfman

In 1527 the Elector Johann of Saxony dispatched assistance to Ferdinand, king of Bohemia and Hungary, to relieve Vienna from the besieging Ottoman army. In doing so he ignored the deep and ongoing dispute over the German church in order to prevent possible catastrophe at the hands of the Ottoman Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent. At the head of that column rode his son, the Duke Friedrich, who at sixteen was given nominal command of the Saxon forces. Thus, a new player entered onto the stage of European politics, whom we must pause to introduce. Notably, this was not Friedrich’s first experience in arms: two years before, Friedrich had participated personally with his father in the Battle of Frankenhausen against the rebellious peasants. While generations of patriotic embellishment have made the youthful Friedrich’s feats of arms against Muentzer’s poorly armed farmers into the stuff of myth, and can by no means be credited, we do know that at Frankenhausen he personally bore arms and faced the enemy.

Then in 1526, the young duke had apparently argued strenuously following the apocalyptic Battle of Mohacs and the death there of Louis II, King of Bohemia and Hungary, for his father to put himself forward as a candidate to succeed him against the Archduke Ferdinand and the Elector of Bavaria. He was overruled by Johann’s more senior counselors, but Friedrich’s appeal to his father marked, if not the beginning, then at least the preface, of the century-long struggle of the Wettins for the Bohemian throne. One can only imagine then the thoughts that filled young Friedrich’s head as he rode from his father’s court at Torgau south through Bohemia to Vienna to fight alongside Ferdinand, when had his advice the previous year been accepted he might at that moment be riding through the countryside of his patrimony.

Next, we know the duke Friedrich acceded to a scheme of his mother’s that his younger brother and not himself marry the ducal princess Sybille of Cleves. The decision to marry Sybille to the younger, not the elder, brother first seemed to forecast that the pattern of the elder generation would be repeated, with Saxony staying united under a single prince, with one brother ruling and the other providing legitimate heirs for the next generation. However, this was not the design of any of the principles: the Electress Elizabeth was still madly intent upon a royal match for her first-born, her first preference being her niece, the Princess of Wales.

For entirely different reasons did this plan appeal to the rest of the court: marrying Johann the younger to the eldest daughter of the Duke of Juelich-Cleves-Marck-Ravensburg meant that prosperous and significant patrimony might pass to his and Sybille’s heirs, if her brother Wilhelm died without heirs of his body. Thus, rather than Electoral Saxony facing further partition between the two brothers in a repeat of 1485, or one brother being kept subordinate to the other as the elder Johann had been to the elder Friedrich until the latter’s death in 1525, it was possible the younger brother might enjoy rule without partition through his marriage to the House of Marck. And given Sybille’s brother Wilhelm was still only a boy of ten, that possibility was very real. Moreover, Johann the Younger was personally given Sybille's enormous dowry, making his personal wealth greater than many ruling princes of the empire.

Many of these calculations took for granted that Friedrich the younger would inherit from his father the Elector Johann. Despite the apparent closeness of father and son, that was thrown into grave doubt by the Karlstadt scandal of 1528-9, when it was discovered the young duke had given financial support to the radical reformer Andreas Karlstadt long past Luther’s break with him and his exile from Saxony. Moreover, a search of the young duke’s apartments in Torgau yielded correspondence from Karlstadt in which he both provided spiritual advice to Friedrich and referred to certain promises the duke had made as to preferments he would be given once Friedrich came to power.

In this shocking turn of events, the disparate and warring authorities in Friedrich’s world for once sprung to life and acted as one: his father the Elector, his mother, and Luther himself, alternately beseeched and demanded that he leave his interest in such radicalism behind. Moreover, quite apart from that, the Elector Johann ordered armed men to the small farm on which Karlstadt and his family had lived since the Peasants War. He was seized and put on trial for his role in disturbing the peace of Saxony, and made out on dubious evidence to have been a co-conspirator of Muentzer. Found guilty, Luther’s former colleague at the Leucorea, for whom Luther’s wife Katarina von Bora had stood as godmother to his children, was executed. Plainly, the electoral court believed this the only outcome that would safeguard the religious innovations from a descent into radicalism that would unite all Europe into a crusade against them.

Truly shaken by the possibility the electoral dignity might pass to his younger brother, and that such a disinheritance might occasion sterner measures yet against his person and even the end of his own life, young Friedrich whether as a feint or in complete sincerity, offered no resistance to his father and mother. He swore to uphold the more than symbolic presence of the body of Christ in the Eucharist, to guard against any iconoclastic disorders, to stand adamantly against adult baptism, and otherwise to heed to Christian orthodoxy as Luther defined it. However, as would later become obvious, the celebrated episode of Doctor Karlstadt put an end to whatever pretensions to closeness existed between Luther and the heir of Electoral Saxony.

Young Friedrich nonetheless signed his name to the Augsburg Confession alongside his father’s in June 1530, essentially ratifying his public belief in Lutheran doctrine, though in certain notorious later marriage negotiations of his own he would protest this was under duress. With the Elector Johann’s health in rapid decline during 1531, Friedrich was left to coordinate the Protestant response to the Confutation presented by scholars loyal to Rome to the Augsburg Confession. However, rather than trying in any way to confer his own intellectual or spiritual imprimatur, Friedrich permitted Philip Melanchthon to take the doctrinal lead, beginning his long tendency to promote him at Luther’s expense. Regardless, enough confidence in Friedrich had been restored among the Lutheran establishment that when the Elector Johann the Steadfast died on August 19, 1532, there was no serious question of his succession.

Knowledge of the Karlstadt affair only began to spread beyond the electoral court following the discovery of certain letters among the effects of the Electress Elizabeth after her death in 1550. The veracity of the events were not admitted until long after Friedrich IV’s death, and to this day the preferred version of events among Lutheran historians is that Friedrich’s enthusiasm for Karlstadt’s ideas represented a youthful experiment, and not representative of his opinions in later life.

Last edited:

Interesting start...

Waiting for more, and hopefully it's as detailed as the last version of this was...

Yeah, one of the issues the old timeline had was that the beginning was extremely sketchy, with the most pivotal figures in the timeline dispatched in a post or two, without even the cursory details of their lives addressed. So actually what we're going to do is provide more detail in the beginning, so hopefully that makes what follows more concrete. We're also going to scale down things in the beginning, so that the outward ripples of these events in Central Europe are a bit more modest. Hopefully, that will also make it more realistic. Thanks!

Threadmarks

View all 109 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Supplemental Note on Contemporary Crime, New Amsterdam Supplemental Note, The Construction of the Elbe Underpass, 20th Century Supplemental on the History and Goverment of New Amsterdam The Life of Elector Alexander of Saxony, 1566-1567 The Life of Elector Alexander of Saxony, 1567-1571 The Life of Julius of Braunschweig, 1550-1571 Supplemental Note on the Contemporary German Imperial Monarchy The Life of the Elector Alexander of Saxony, 1569-1573

Share: