Small arms

The early Army carbines used cartridges that were not too different from the standard rifle ones (Springfield Model 1855/1863 – 15 mm, 500 gr, 370 m/s max, 22.18 J, 19.6 J/mm2). For example, the branded linen cartridge .52 Sharps of 1852 (13 mm, 475 gr, 370 m/s, 2107 J, 15.377 J/mm2).

However, the rifle cartridge was not suitable for a carbine. A large charge of the rifle cartridge did not have time to burn out when the bullet was already leaving the short carbine barrel. And the great power of the rifle cartridge led to a significant recoil of a light carbine.

Therefore, Christopher Miner Spencer used the short cartridge .56-56 Spencer (14x22RF, 350 gr, 370 m/s, 1545 J, 10.546 J/mm2) for his 1860 repeating carbine. Another of his considerations was that a fast-firing repeating weapon would require more ammunition which means a each separate cartridge should be lighter.

The Civil War made own corrections to the methods of employment the small arms and to the requirements for its characteristics. At the beginning of the war the soldiers of both armies were too inexperienced to maintain a tight formation after start of attack. And at the end of the war they became too experienced to do this. Usually didn’t open fire “until see the enemy’s eyes” or “buttons on his uniform”.

Prior to attack the troops were still aligning in several lines but with the start of attack the own indiscipline, American individualism, wooded terrain, and simply ardor forced them to disperse. Fortunately, officers who were accustomed to dealing with uncontrollable crowds of recruits from the very beginning of the war not only had recognized to what degree the command principle should be preserved and with which degree to take advantage of soldier’s personal initiative but also has appreciated the dispersed formations.

A similar course of action characteristic and natural for the American army from the very first battles of the War of Independence was caused not much of low discipline and weak training but of resistance to the British generals' attempts to draw the Continental Army into unprofitable for it the general battle according to the European model. The Americans used guerrilla tactics, made unexpected ambushes, withdrawals, and quick crossings, attacked at night and in bad weather relied solely on small arms fire, not on the usual bayonet attack after the platoon salvo. American commanders actively used the experience of encounter with the Indians. Their small detachments were achieved the defeat of entire British companies and even of regiments.

Thus, targets for long-range fire on the battlefields of the Civil War just did not exist.

In general, touching upon the issue of competition between accuracy and rate of fire it must be said that even the armies of the time of the muskets no longer practiced high-precision shooting since the possibilities to increase the accuracy of smooth-bore weapons were rested by constructive level of the ballistic part. At the same time the rate of reloading was a variable and depended on the training of the shooter and could also be increased by special devices. Therefore, the progress of small arms already then was concentrated more on the speed of reloading and on producing as many shots as possible without cleaning the barrel.

All of this depreciated the long-barrel army rifle. Created "based on" a smooth-bore musket for which only a barrel length allowed some accuracy at the slightest acceptable range the initial army rifle just mechanically copied this length. But no longer existed the tight formations to which could be fired by volleys from a kilometer. The Unionists and Confederates fired at each other for the mostly with 100 or less yards. Rifled weapons did not need the same barrel length for this. It quickly became clear that the shooter's capabilities are limited not by his weapon's barrel length but by the features of human vision, by the imprecision of the musculoskeletal system, and by the psycho-emotional impact of combat. And that regardless of the stand-on ballistic performances of the weapon, a mass-trained shooter is capable of effectively striking even an open advancing enemy at a distance of no more than about 100 yards. At a range of near 300 yards only about half of the bullets reached the target. More long range fire was already ineffective and, according to the military, led to inefficient ammunition consumption.

Therefore, increasing of range was fundamentally impossible. It was clear that to further improving the efficiency of small arms was much more important to bet on other qualities. The probability of a soldier's survival was all the more the fewer opponents remained around him. And this probability increased as faster as faster was decreasing the opponents around him. Therefore, the rate of fire and, as a result, large carried ammunition became more important. A short range of fire required a short barrel, and that, in turn, required a short cartridge. And the Americans just got a weapon that answers the new requirements - magazine carbines.

The long-barreled rifle did not become also a satisfactory weapon for group fire at the concentrated formations of the enemy, which its adherents saw in it. Previously, firing by platoon at up to 300 yards the shooter could observe more or less the result of his shooting and adjust it. Observation of the results was required for management of group firing by the commanders too. Now, shooting at a kilometer range the shooter had to aim at a barely noticeable target which angular size was smaller than the size of the sight and the inability to accurately superpose the target with the sight became an obstacle to accuracy. In addition, the observation of such small targets at the edge of the muzzle-sight is accompanied by their blurring. But a deviation of only one mil (0.06 degrees) at one kilometer gives miss of one meter. This means that even if the target is a dense and vast crowd, it is only a thin thread at this distance, and most of the bullets will be lied undershoots or fly higher. But neither the shooter nor the commander will be able to notice this and will not be able to correct the fire. And what kind of correction is possible here, if such deviations make each shot individual, depending on factors such as hand shake, wind, deviations in the weight and in the moisture of the gunpowder - which cannot be taken into account in the bustle of battle, or simply detected at such a distance? This is shooting “somewhere in that direction,” or, as was used to say in those ages, “shooting without an exact target,” “shooting to a heap.

European realities also led to notion that the highest ballistic-energy qualities are not a priority for small arms. "The first significant impetus to rearmament became the Austro-Prussian war of 1866 in which the Prussians has weaker in the number of troops, had also relatively weak artillery and the needle rifles which inferior to the Austrian both in range and accuracy but was more quick-fire in comparison with the Austrians and which gave a double fire speed against those. And now this one advantage of the density of rifle fire paralyzed all the other advantages of the Austrian weapons and greatly contributed to the complete victory of the Prussians. " (I. Blioch. "Future war in technical, economic and political relations". 1898. Vol. 1, p. 21. Reference to Oméga, "L'art de combattre", p. 36). However, Europeans did not pay attention to this advantage at all. In the Austro-Prussian War only a few saw the non-mandatory of high energy and no one saw the urgency of abandoning it. None of the battles waged by the Europeans until 1915 caused them to strive to reduce the energy of small arms.

The long rifle did not become for the Americans a bayonet handle also. Cold steel arms were practically not used in the Civil War. From 1861 to 1865 more than 90% of wounds were inflicted by small arms, and most of the remaining was non-combat. "I think half a dozen would include all the wounds of this nature that I ever dressed,” wrote surgeon Major Albert Hart about bayonet wounds. Whereas the prevailing notions about a fighting in Europe were such that even half a century later the infantry lie down in mass under machine gun fire, being obliged by statute to draws close to the enemy in order to destroy it by a bayonet.

Significant consequences for the formation of a new image of small arms had changes that occurred during the Civil War in the methods of cavalry operations. Archives claim that in all four years of the war less than one thousand wounded with saber wounds were received in federal hospitals. This revolution was explained by the fact that the use of small arms was commonplace for the American: protection from the Indians, contentions with neighbors for theft of livestock, urban crime. There was a huge amount of firearms in private use. The saber was rather a parade weapon for ordinary American. The bulk of the warring were volunteers and there was no time to train them of horseback formation and saber wisdom. Only the regular part of the federal cavalry was "correct." Therefore, when in April the 1863rd the 70 John Mosby's rangers was attacked by federal squadron at Michel Farm the sabers did not have time to work out - the northerners were banally shot by revolvers.

The saber attacks on an enemy armed with quick-firing cartridge-percussion weapons were insanity. Cavalry commanders quickly realized that was better to use horses not for frontal attacks but for quick advancement to the place of a possible encounter with the enemy. Approached the enemy the cavalrymen dismounted and then fought like ordinary infantrymen. Civil War generals revived the formation of dragoons or rather mounted infantry and very successfully used them. Cold steel adherents were defeated by commanders familiar with the new cavalry style of action. Dragoons being the cavalry were armed with carbines.

On June 9, 1863, took place a cavalry battle at Brandy station which became the largest in the entire war. 12 thousand cavalrymen took part in it from the southerners' side and about 15 thousand from the northerners. This battle is notable for the fact that the troops of both sides fought mainly in foot formations.

Dragoons were, of course, not an American invention. And it was not the Americans who were the first to speak out about the impossibility of waging cavalry fights with cold steel - this was said by the generals of the Napoleonic era already: "...with the improvement of firearms, the cavalry loses its significance more and more." However, during the Civil War this has completely transform cavalry and its weapons. There were particular units that even over carbine preferred more short-barreled revolvers, for example the Mosby Rangers.

In 1864, the Springfield Arsenal developed a new short cartridge .56-50 (13x29RF, 350 gr, 375 m/s, 1595 J, 12.648 J/mm2) with improved ballistics. By the end of autumn 1864, .56-46 (12x27RF, 330 gr, 368 m/s, 1448 J, 12.718 J/mm2) was developed. The bullet's Josserand Energy Delivery Index and with this the fighting qualities where increased despite the reduction of caliber, precisely speaking due to this exactly.

After the war the US Army fell into its usual lethargic state again, and that positive processes which during the fighting began in regarding to the optimization of small arms would seem should have stopped. In absence of the combat practice requirements a short weapon would seem should no longer be able to compete with the standard long-barreled Springfield. But just when the Army ceased to need of a huge quantity of whatever any suitable weapon then an army rifle largest alternative arose.

The fact is that the peacetime opponents of the Army and the militia - the “gentlemen of fortune” and the Indians - preferred commercial models. First of all - with the huge Americans love for shooting - due to the cheapness of less powerful ammunition. Savings also attracted states authorities when arming the militia. In addition, commercial models far exceeded standard army ones in their development.

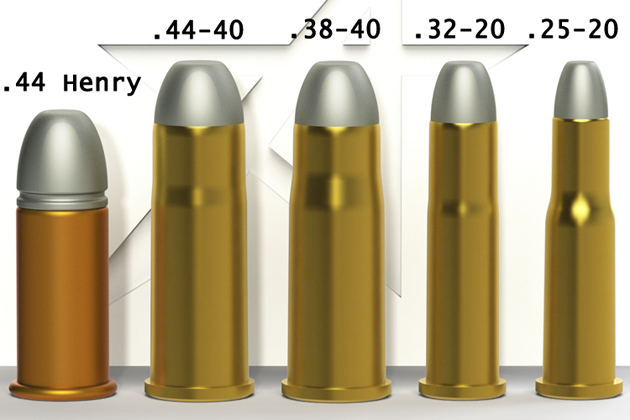

The most popular among commercial weapons were the products of Henry/Winchester. The Winchester Company picked up the baton of Henry rifle production and released a slightly modified Model 1866 for the same .44 Henry (11 × 23RF, 200 gr, 340 m/s, 749 J, 7.47 J/mm2). Then it was replaced by Model 1873 in the more powerful .44-40 (11x33CF, 200 gr, 379 m/s, 931 J, 10.16 J/mm2). However, cheaper ammunition was still a commercial success so already next year it was adapted for .38-40 (10x33CF, 180 gr, 350 m/s, 714 J, 8.74 J/mm2)

The perspective to oppose with the single-loader against light quick-firing repeating weapons not really smiled to militiamen. The current enemy did not provided for shooters the grouped targets in the form of infantry formations and the long barrel became already absolutely inappropriate. It would also be ridiculous try to act on foot against mounted bandits and Indians. Here was needed the mounted infantry that appeared in the Civil War, and this affect on constitution of small arms - the cavalry came with their own short-barrel. Besides naturally that many times reduced Army has considered redundant primarily everything non-standard. The carbine with its short cartridge became out of alternative.

In 1876 broke out the next Indian - the Black Hills War - in which the Indians inflicted to the Army a number of defeats which had a huge resonance in society and in government structures. The reasons for the defeats were outside the issue of the weapons quality, but for some accounts were voiced only secondary technical reasons: insufficient amount of carried ammunition of oversize cartridges and insufficient rate of fire - all this of course with the enemy “huge quantitative superiority”. So two weeks after the most loud failure, the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25 - 26, one of the newspapers stated that the soldiers would not have been defeated if they had been armed with Russian-type Smith and Wesson revolvers with automatic case extraction. Others talked about Winchesters and Evans rifles, about double-action revolvers. Also were blamed that Colonel Custer didn’t take two of his Gatling into a raid.

The senators made a fuss. The Army was forced to respond. The Ordnance Department board of officers was appointed. The competition for new weapons for the Army was announced. The requirements were fully matched to the "public request": increasing both the rate of fire and carried ammunition.

And then the work of the board dragged on - on the one hand due to the lack of a clear idea on the military about what they needed and on the other hand because the Army was not satisfied with the samples coming to the competition. It was only clear that the cartridge should have been the smallest with a lethal capacity on the manpower not inferior to the standard .56-46. And then was decided that since the Army was defeated by the .38-40 Winchester, turns out so it satisfies this condition. This cartridge was standardized for the new Army weapons being developed.

While the competition continued Winchester launched on the market the Model 1882 in an even cheaper .32-20 (8x33CF, 100 gr, 370 m/s, 444 J, 8.958 J/mm2). The line of this cartridge in 1885 was supplemented by .25-20 as well as .22-20 (.22 Winchester Center Fire - 5.6x35CF, 45 gr, 470 m/s, 322 J, 12.19 J/mm2) whose penetrating ability conformed to standard .56-46.

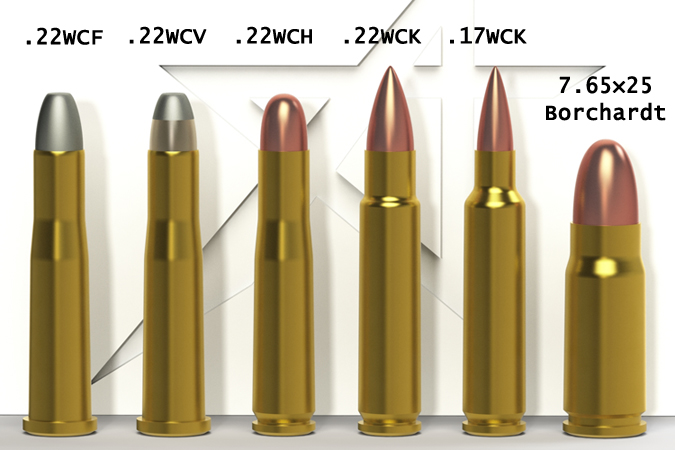

But in the same year R. Harwood tried to achieve maximum lethal force and accuracy at a short barrel and minimal recoil exactly at optimal range for small arms of up to 300 yards. A long time series of experiments led to the conclusion that with 22 grains of black gunpowder .22WCF behave unpredictably sometimes. The results suggested him that a charge of smokeless powder would increase efficiency greatly. The company management decided that such cartridge would be a complete success in production. The smokeless Schulze powder which was available on the market in abundance already, although considered by the military to be still dangerous during storage, was taken, and 22WCF charged with them gave .22 Winchester Center fire Velocity (40 gr, 630 m/s, 514 J, 20,14 J/mm2) [real prototype - .22 Harwood Hornet]. The bullet had to be made semi-jacketed due to disruption from rifling at an increased muzzle velocity. In view of penetration this ammunition not only surpassed previous carbine cartridges but was not inferior to wartime infantry cartridges with the Minié bullet. The board became interested in the cartridge.

Soon, however, began a movement to ban of soft lead bullets which flattened in the target body and half-jacketed bullets which has expansive effect. Both of them inflicted the severe wounds and were declared inhumane. As a result the bullet was made completely jacketed. More advanced smokeless powder burning faster than the European one and created specifically for the short American army barrel was used also - all this in 1894 gave .22 Winchester Center fire High-velocity [real prototypes - .22 Vierling/.22 Hornet]. The rim was replaced by a groove.

And after the War with Spain in 1899 the cartridge was redesigned according to the latest trends and in order to full use of its size. The former case had a long neck and a short body. At the new case the body was lengthened due to shortening of the neck. Both, its volume and its power increased. Performances of .22 Winchester Center fire Kurzpatrone named after the ideological foundation of the American view on small arms was 35 gr, 750 m/s, 638 J, 25 J/mm2 [real prototypes - 5.6x34R Francotte/.22 K-Hornet]. With a maximum case diameter of 7.57 mm two-row magazine contained 26 rounds.

At this time cartridge S.A. Ball .303 Cordite Mark V of 1899 for British infantry Magazine Lee-Enfield had 7.92x56CF, 215 gr, 628 m/s, 2745 J, 55.744 J/mm2. That is for a 2.3 times greater penetration ability which was absolutely overabundant the English cartridge should have been 4.3 times more powerful. Wherein, if the carried ammunition standard for a British soldier in the Second Boer War was 100 rounds .303 then for the same weight could be taken 275 rounds .22WCK.

The Old World military were blinded by a long-barrel rifle. Also, being intended for assault operations, the Borchardt Construktion 93 was not suitable as a personal defense pistol. It remains only to offer it as a "hunters and travelers" weapon. Although its case was same volume as .22WCK, European realities led to a larger caliber: 7.65×25 Borchardt had 85 gr, 390 m/s, 423 J, 8.72 J/mm2. Therefore, the combat properties of Borchardt were completely incomparable with the American "pistol". The .22WCK had almost 3 times more penetration ability and was closer in this respect to a rifle than to an ordinary pistol, ideally matching the definition of assault weapons given by Hebler and Krnka.

That part of the army functionaries which was not burdened by education from the fact of reducing the small arms power as a result of the transition to the assault pistol innocently deduced the sense about a corresponding decrease its effectiveness. While ballistics connects the increase in effectiveness directly with a decreasing in caliber and pointed to a decreasing in caliber as to effective mean of retention the efficiency while reducing the energy of ammunition. Studies conducted at the same time in Europe showed that the distance to the target in battle is often only known approximately and aiming is done on a target that is not clearly visible. Therefore, increased accuracy at an optimal range for individual infantry weapon is required more likely than the conservation of bullet energy at a distance exceeding the optimum. Accuracy comes from the flatness of the trajectory and from long range of a direct shot. The declivous of the trajectory, in turn, depends on the initial velocity and on the Josserand Energy Delivery Index of the bullet. And to velocity increasing the possible greatest relative charge is required. So the charge, that is, the cartridge can be reduced, the main thing is to reduce the weight of the bullet accordingly. But so that the Josserand Energy Delivery Index does not decrease, it is necessary to reduce the caliber. Therefore both desire to the growth of carried ammunition and the desire for greater flatness requires reducing the caliber. However the less the bullet weighs the faster it loses speed. Therefore is necessary that the triad "charge energy/bullet weight/caliber" be conformed to the required firing range. And the .22WCK cartridge was created just for that its triad conforms to the maximum range of effective fire of individual infantry weapon - 300 yards.

Wherein, despite to measures of prevent a severe wounds, it turned out that the new bullet still inflicts more severe wounds than the previous bullets two to three times larger caliber, even soft ones. As said then time the wounds has explosive nature or "caused by the action of hydraulic pressure." At first it was attributed to the action of high speed. But in the first decade of the new century using instant photography to study the flight of a bullet the German scientists discovered its precession. It turned out that the bullet whose length is close to the caliber, moves almost in the same way as the spherical one since its center of gravity and the center of resistance practically coincide which determines the channel of its passage in the target’s body as a straight and almost regular in section even in case of destabilization. Whereas on an elongated precessing bullet in impact with the target acts a destabilization forces. With a decreasing of the rotation speed due to braking in the solid body of the target the bullet is destabilized even more. And if a bullet of a European cartridge at an optimal range of up to 300 yards still keep sufficient stability to in most cases accurately pass through the target body then the light .22WCK bullet loses rotational energy faster, becomes unstable and its passage channel shows the deflection and sideways movement on a part of the path. The latter leads to a sharp increasing of resistance and as a result to a hydrodynamic shock which forms a cavitation chamber in the target body which makes the wound extremely severe. Because of this the damaging effect .22WCK even surpasses that of powerful European cartridges.

In addition, a decreasing of the capacity of the small arms of the US Army would have provided a cause for concern, being implemented on its own. But the fact is that this process was only a reaction to at the same time happening adoption of the main shooting duty by infantry artillery, by its new weapon - a machine gun.

By the 1890s in Europe the development of small arms had become more than a way through inferences witch based on practice - in it was intervened the force of a higher order - a science. But the machine gun was not yet widespread at all and the Europeans did not realize the true meaning of this automate as a result of which they remained committed to group long-range rifle fire. Therefore, European ballistics were mainly occupied not with the search for an optimal cartridge but only with a unidirectional increasing of its ballistic-energetic characteristics which resulted in a decrease in caliber while saving a large volume of powder charge. Now, since the decrease in caliber was justified the European ballistics went in this all the way: in 1891 in Italy a cartridge of 6.5 mm caliber was adopted, and was argued the need for further reduction, and experiments were conducted with calibers of 5 mm and less. However, with a decreasing in caliber while saving the volume of the charge the pressure of the powder gases in the experimental European rifles increased over 60,000 PSI which made difficult to design the weapon of such calibers. At the same time the initial velocity of bullets of ultra-small-caliber cartridges increased significantly but their residual velocity felled too quickly from the point of view of fire to long distances. These two factors stopped the process of reducing the caliber of small arms in Europe.

The American approach to small arms was distinguished from the European one by the absence the practice of long-range fire on the tight formations, by the concentration of fire on individual targets, and as a result by the practical effective range of 300 yards. This was conditioned a lower volume of the powder charge, and therefore a lower gas pressure - the WCK cartridge necked down to .17 inch (4.4×35CF, 30 gr, 900 m/s, 787.3 J, 52.6 J/mm2) [real prototype - .17 Hornet] was producing no more than 48,000 PSI. And, of course, the Americans were not concerned with the residual speed beyond the practical effective range of fire. But within the required range the new ammunition was not inferior to modern oversize European rifle cartridges by its damaging effect. This was the last change of the American army cartridge in its case form.