Wonder how Pellegra effected the Confederacy's war efforts during the Great Wars?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Photos from Featherston's Confederacy/ TL-191

- Thread starter Alternatehistoryguy47

- Start date

-

- Tags

- the rising sun

FanOfHistory

Banned

It's weird that Turtledove doesn't mention Pellagra in the GW books. I think he may have mentioned it in the later books, but I'm not sure. Obviously, this disease is going to be a major problem for the Confederacy.Wonder how Pellegra effected the Confederacy's war efforts during the Great Wars?

It's weird that Turtledove doesn't mention Pellagra in the GW books. I think he may have mentioned it in the later books, but I'm not sure. Obviously, this disease is going to be a major problem for the Confederacy.

Indeed. Pellagra should've sapped the Confederate manpower to such an extent that continuing the war should've been impossible.

A rare photo of one of the countless football games played between American and Confederate troops during the 1914 Christmas truce. The location is unknown, but due to the flat topography present and the lack of visible trench lines it has long been assumed to be from the front in Sequoyah.

Lincoln's Warning

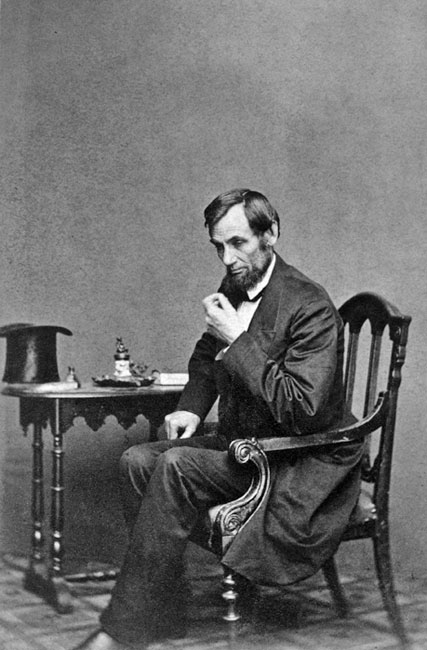

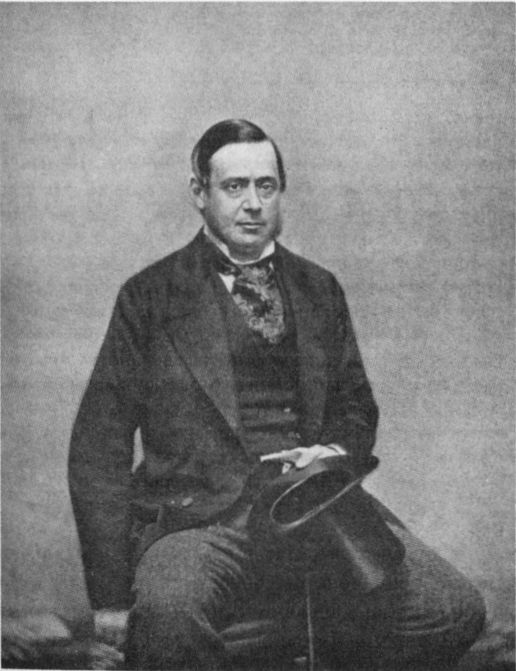

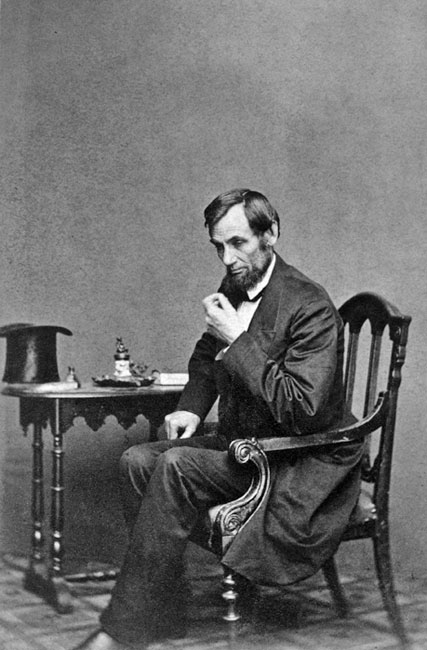

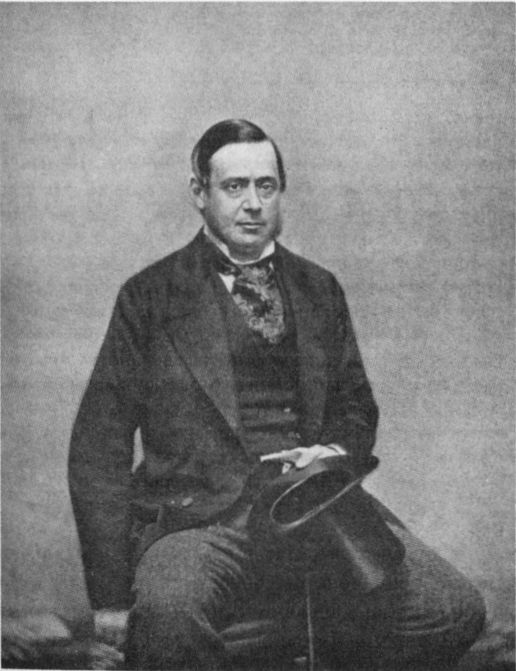

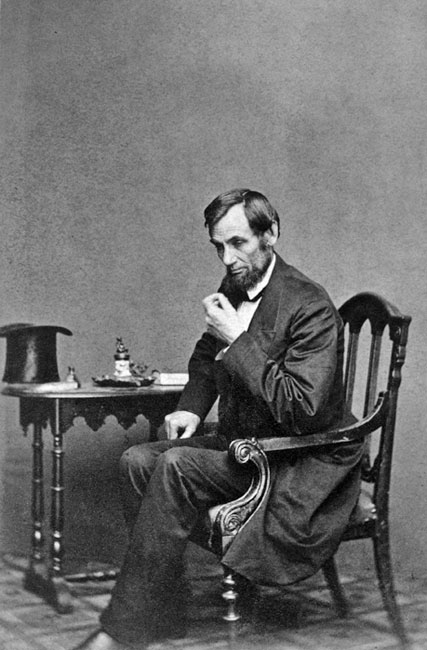

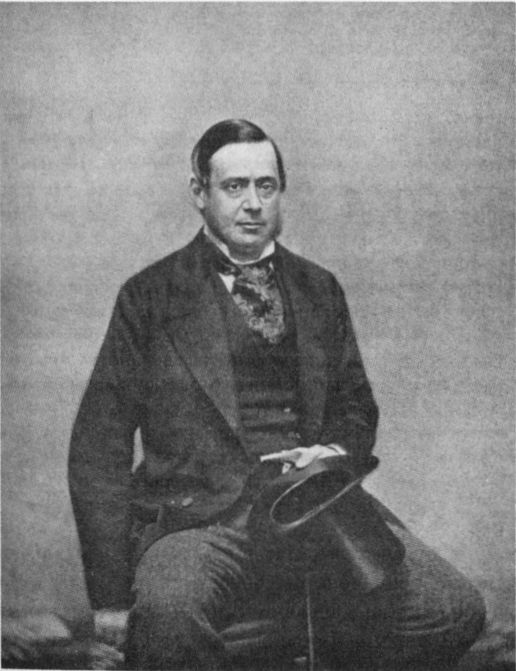

Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America...……...Richard Lyons, 1st Viscount Lyons, British Minister to the United States

Setting: Executive Mansion, Washington, D.C.—4 NOVEMBER, 1862

Prelude to American Front, pgs. 4-9 HARDCOVER EDITION

BONUS: John Nicolay was a real person: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_George_Nicolay

Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America...……...Richard Lyons, 1st Viscount Lyons, British Minister to the United States

Setting: Executive Mansion, Washington, D.C.—4 NOVEMBER, 1862

Both horses that brought Lord Lyons’ carriage to the Executive Mansion were black. So was the carriage itself, and the cloth canopy stretched over it to protect the British minister from the rain. All very fitting, Lord Lyons thought, for what is in effect a funeral.

“Whoa!” the driver said quietly, and pulled back on the reins. The horses, well-trained animals both, halted in a couple of short, neat strides just in front of the entrance of the American presidential mansion. The driver handed Lord Lyons an umbrella to protect himself against the rain for the few steps he’d need to get under cover.

“Thank you, Miller,” Lord Lyons said, unfurling the umbrella. “I expect they will make you and the animals comfortable, and then bring you back out here to drive me off to the ministry upon the conclusion of my appointment with President Lincoln.”

“Yes, sir,” the driver said.

Lord Lyons got down from the carriage. His feet splashed in the water on the walkway as he hurried toward the White House entrance. A few raindrops hit him in the face in spite of the umbrella. Miller chirruped to the horses and drove off toward the stable.

In the front hall, a colored servant took Lord Lyons’ hat and overcoat and umbrella and hung them up. John Nicolay stood waiting patiently while the servant tended to the British minister. Then Lincoln’s personal secretary said, “The president is waiting for you, sir.”

“Thank you, Mr. Nicolay.” Lord Lyons hesitated, but then, as Nicolay turned away to lead him to Lincoln’s office, decided to go on: “I would like the president to understand that what I do today, I do as the servant and representative of Her Majesty’s government, and that in my own person I deeply regret the necessity for this meeting.”

“I’ll tell him that, Your Excellency.” Nicolay sounded bitter. He was a young man—he could hardly have had more than thirty years—and had not yet learned altogether to subsume his own feelings in the needs of diplomacy. “When you get right down to it, though, what difference does that make?”

When you got right down to it (American idiom, Lord Lyons thought), it made very little difference. He was silent as he followed Nicolay upstairs. But for the personal secretary and the one servant, he had seen no one in the Executive Mansion. It was as if the rest of the staff at the presidential mansion feared he bore some deadly, contagious disease. And so, in a way, he did.

John Nicolay seated him in an antechamber outside Lincoln’s office. “Let me announce you, Your Excellency. I’ll be back directly.” He ducked into the office, closing the door after himself; Lord Lyons hoped he was delivering the personal message with which he had been entrusted. He emerged almost as quickly as he had promised. “President Lincoln will see you now, sir.”

“Thank you, Mr. Nicolay,” Lord Lyons repeated, striding past the secretary into the office of the president of the United States.

Abraham Lincoln got up from behind his desk and extended his hand. “Good day to you, sir,” he said in his rustic accent. Outwardly, he was as calm as if he reckoned the occasion no more than an ordinary social call.

“Good day, Mr. President,” Lord Lyons replied, clasping Lincoln’s big hand in his. The American chief executive was so tall and lean and angular that, merely by existing, he reminded Lord Lyons of how short, pudgy, and round-faced he was.

“Sit yourself down, Your Excellency.” Lincoln pointed to a chair upholstered in blue plush. “I know what you’re here for. Let’s get on with it, shall we? It’s like going to the dentist—waiting won’t make it any better.”

“Er—no,” Lord Lyons said. Lincoln had a gift for unexpected, apt, and vivid similes; one of the British minister’s molars gave him a twinge at the mere idea of visiting the dentist. “As Mr. Nicolay may have told you—”

“Yes, yes,” Lincoln interrupted. “He did tell me. It’s not that I’m not grateful, either, but how you feel about it hasn’t got anything to do with the price of whiskey.” He’d aged ten years in the little more than a year and a half since he’d taken office; harsh lines scored his face into a mask of grief that begged to be carved into eternal marble. “Just say what you’ve come to say.”

“Very well, Mr. President.” Lord Lyons took a deep breath. He really didn’t want to go on; he loathed slavery and everything it stood for. But his instructions from London were explicit, and admitted of no compromise. “I am directed by Lord Palmerston, prime minister for Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, who is, I am to inform you, operating with the full approbation and concord of the government of His Majesty Napoleon III, Emperor of France, to propose mediation between the governments of the United States and Confederate States, with a view to resolving the differences between those two governments. Earl Russell, our foreign secretary, generously offers himself as mediator between the two sides.”

There. It was said. On the surface, it sounded conciliatory enough. Below that surface—Lincoln was astute enough to see what lay below. “I do thank Lord Palmerston for his good offices,” he said, “but, as we deny there is any such thing as the government of the Confederate States, Earl Russell can’t very well mediate between them and us.”

Lord Lyons sighed. “You say this, Mr. President, with the Army of Northern Virginia encamped in Philadelphia?”

“I would say it, sir, if that Army were encamped on the front lawn of the Executive Mansion,” Lincoln replied.

“Mr. President, let me outline the steps Her Majesty’s government and the government of France are prepared to take if you decline mediation,” Lord Lyons said, again unwillingly—but Lincoln had to know what he was getting into. “First, the governments of Great Britain and France will immediately extend diplomatic recognition to the Confederate States of America.”

“You’ll do that anyhow.” Like John Nicolay, Lincoln was bitter—and with reason.

“We shall do more than that, at need,” the British minister said. “We are prepared to use our naval forces to break the blockade you have imposed against the Confederate States and permit unimpeded commerce to resume between those states and the nations of the world.”

“That would mean war between England and France on the one hand and the United States on the other,” Lincoln warned.

“Indeed, it would, Mr. President—and, as the United States have shown themselves unequal to the task of restoring the Confederate States to their allegiance, I must say I find myself surprised to find you willing to engage in simultaneous conflict with those Confederate States and with the two greatest powers in the world today. I admire your spirit, I admire your courage, very much—but can you not see there are times when, for the good of the nation, spirit and courage must yield to common sense?”

“Let’s dicker, Lord Lyons,” Lincoln said; the British minister needed a moment to understand he meant bargain. Lincoln gave him that moment, reaching into a desk drawer and drawing out a folded sheet of paper that he set on top of the desk. “I have here, sir, a proclamation declaring all Negroes held in bondage in those areas now in rebellion against the lawful government of the United States to be freed as of next January first. I had been saving this proclamation against a Union victory, but circumstances being as they are—”

Lord Lyons spread his hands with genuine regret. “Had you won such a victory, Mr. President, I should not be visiting you today with the melancholy message I bear from my government. You know, sir, that I personally despise the institution of chattel slavery and everything associated with it.” He waited for Lincoln to nod before continuing, “That said, however, I must tell you that an emancipation proclamation issued after the series of defeats Federal forces have suffered would be perceived as a cri de coeur, a call for servile insurrection to aid your flagging cause, and as such would not be favorably received in either London or Paris, to say nothing of its probable effect in Richmond. I am truly sorry, Mr. President, but this is not the way out of your dilemma.”

Lincoln unfolded the paper on which he’d written the decree abolishing slavery in the seceding states, put on a pair of spectacles to read it, sighed, folded it again, and returned it to its drawer without offering to show it to Lord Lyons. “If that doesn’t help us, sir, I don’t know what will,” he said. His long, narrow face twisted, as if he were in physical pain. “Of course, what you’re telling me is that nothing helps us, nothing at all.”

“Accept the good offices of Her Majesty’s government in mediating between your government and that of the Confederate States,” the British minister urged him. “Truly, I believe that to be your best course, perhaps your only course. As Gladstone said last month, the Confederate States have made an army, a navy, and now a nation for themselves.”

With slow, deliberate motions, Lincoln took off his spectacles and put them back in their leather case. His deep-set eyes filled with a bitterness beside which that of John Nicolay seemed merely the petulance of a small boy deprived of a cherished sweet. “Take what England deigns to give us at the conference table, or else end up with less. That’s what you mean, in plain talk.”

“That is what the situation dictates,” Lord Lyons said uncomfortably.

“Yes, the situation dictates,” Lincoln said, “and England and France dictate, too.” He sighed again. “Very well, sir. Go ahead and inform your prime minister that we accept mediation, having no better choice.”

“Truly you will go down in history as a great statesman because of this, Mr. President,” Lord Lyons replied, almost limp with relief that Lincoln had chosen to see reason—with Americans, you never could tell ahead of time. “And in time, the United States and the Confederate States, still having between them a common language and much common history, shall take their full and rightful places in the world, a pair of sturdy brothers.”

Lincoln shook his head. “Your Excellency, with all due respect to you, I have to doubt that. The citizens of the United States want the Federal Union preserved. No matter what the Rebels did to us, we would fight on against them—if England and France weren’t sticking their oar in.”

“My government seeks only to bring about a just peace, recognizing the rights of both sides in this dispute,” the British minister answered.

“Yes, you would say that, wouldn’t you, Lord Lyons?” Lincoln said, freighting the title with a stinging load of contempt. “All the lords and sirs and dukes and earls in London and Paris must be cheering the Rebels on, laughing themselves sick to see our great democracy ground into the dirt.”

“That strikes me as unfair, Mr. President,” Lord Lyons said, though it wasn’t altogether unfair: a large number of British aristocrats were doing exactly as Lincoln had described, seeing in the defeat of the United States a salutary warning to the lower classes in the British Isles. But he put the case as best he could: “The Duke of Argyll, for instance, sir, is among the warmest friends the United States have in England today, and many other leaders by right of birth concur in his opinions.”

“Isn’t that nice of ’em?” Lincoln said, his back-country accent growing stronger with his agitation. “Fact of the matter is, though, that most of your high and mighty want us cut down to size, and they’re glad to see the Rebels do it. They reckon a slaveocracy’s better’n no ocracy at all, isn’t that right?”

“As I have just stated, sir, no, I do not believe that to be the case,” Lord Lyons replied stiffly.

“Oh, yes, you said it. You just didn’t make me believe it, is all,” Lincoln told him. “Well, you Englishmen and the French on your coattails are guardian angels for the Rebels, are you? What with them and you together, you’re too strong for us. You’re right about that, I do admit.”

“The ability to see what is, sir, is essential for the leader of a great nation,” the British minister said. He wanted to let Lincoln down easy if he could.

“I see what is, all right. I surely do,” the president said. “I see that you European powers are taking advantage of this rebellion to meddle in America, the way you used to before the Monroe Doctrine warned you to keep your hands off. Now France and England are in cahoots”—another phrase that briefly baffled Lord Lyons—“to help the Rebels and pull us down. All right, sir.” He breathed heavily. “If that’s the way the game’s going to be played, we aren’t strong enough to prevent it now. But I warn you, Mr. Minister, we can play, too.”

“You are indeed a free and independent nation. No one disputes that, nor will anyone,” Lord Lyons agreed. “You may pursue diplomacy to the full extent of your interests and abilities.”

“Mighty generous of you,” Lincoln said with cutting irony. “And one fine day, I reckon, we’ll have friends in Europe, too, friends who’ll help us get back what’s rightfully ours and what you’ve taken away.”

“A European power—to help you against England and France?” For the first time, Lord Lyons was undiplomatic enough to laugh. American bluster was bad enough most times, but this lunacy— “Good luck to you, Mr. President. Good luck.”

Prelude to American Front, pgs. 4-9 HARDCOVER EDITION

BONUS: John Nicolay was a real person: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_George_Nicolay

Last edited:

I can imagine it would be a somewhat popular POD scenario in-universe among some AH fans for Britain and France not to become such close allies to the Confederacy.Lincoln's Warning

Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America...……...Richard Lyons, 1st Viscount Lyons, British Minister to the United States

Setting: Executive Mansion, Washington, D.C.—4 NOVEMBER, 1862

I can imagine it would be a somewhat popular POD scenario in-universe among some AH fans for Britain and France not to become such close allies to the Confederacy.

Given what Confederate independence brought to not just the United States, but the world, I honestly can't blame them.

Photo taken of the American attack on Pearl Harbor. Ocurring only a few days after the American declaration of war on the Entente nations, the attack caught the British forces on the island completely off guard and unprepared. It was hailed in American newspapers as retribution for the humiliation the Royal Navy had inflicted upon US shores and cities during the Second Mexican War. In contrast, British newspapers reffered to it as the "greatest day of infamy" in the history of the Royal Navy.

From a larger military viewpoint, the attack left the British in the Pacific much more dependent on their Japanese allies than they otherwise would have liked as well as left Western Canada liable to be cut off from aide. In addition it completely threw out pipe dreams for potentially blockading the US West Cost. The US meanwhile now found itself with the long sought after base for projection of its interests into the Pacific.

Last edited:

I can imagine it would be a somewhat popular POD scenario in-universe among some AH fans for Britain and France not to become such close allies to the Confederacy.

The UK most of all. Honesty, they had no real reason to aid the South in the Second Mexican-American War. France because they wanted to keep the Mexican Empire aloft, but the UK had no need to keep aiding the CSA.

That, or have the Union keep fighting the South, and crush Lee. (Forcing Lee to lose control of Philadelphia.)

The US learned from the Trent affair and AFAIK bought their whole wars supply shortly thereafter, they have enough for awhile

Union can still easily win. Lee now has the joy of a long exposed supply line. Assuming the Union can scrape up a decent sized army not led by a moron, the US can park the Army square on Lee's supply line, moved and supplied by sea and he has to abandon Philadelphia to fight it at a place of the Union Commanders choosing, and anything but a crushing victory will end up a strategic defeat. Lee also has the issue of a lot of Pennsylvania militia, ~20,000 off the top of my head, he can beat them in a fair fight, but his foraging parties are going to have to be brigade strength, even if the Union doesn't park an army on his supply lines he may have to leave Philadelphia anyways or whither on the vine

Of course to scrape up that army without stripping the west the US will have to give up on certain tertiary theaters in the short term, which will loosen the blockade

Not just reinforcements but the survivors of the Army of the Potomac. The best casualty ratio the South ever managed in a large battle was 3 to 1 at Fredricksburg, 2 to 1 was Second Bull Run and 2.5 to 1 at Cold Harbor. As long as the AoNV is still combat effective enough to keep moving North than it can't have effectively destroyed the Army of the Potomac, and the AoP probably still outnumbers them, as 87,000 to 55,000, with 3 to 1 casualties to bring odds down to even Lee is still going to suffer in excess of 15,000 casualties, 50% higher than at OTL Antietam

That's in excess of 25% and enough to effectively render AoNV hors de combat. Since the AoNV is not and takes Philadelphia, than the AoTP still outnumbers them, add in Army of the Ohio, Pennsylvania militia and new recruits, and Lee is badly outnumbered

Depends on the aftermath, and how the AoNV behaves. If the AoNV has to retreat South immediately and loses control in Philly, Peace Democrat majority is extremely unlikely. If Lee gets beaten by reinforcements (and he will be in sorry shape after Camp Hill, no bones about it), then no way get a Peace Dem majority

Also depends on why conscription was voted against. If anyone voted for it as unnecessary, well Camp Hill would change their minds, a bit of fear does that

Yeah, all it did long term was make a permanent enemy of a strong nation that cost them Canada and anchored to an alliance with a weak state.The UK most of all. Honesty, they had no real reason to aid the South in the Second Mexican-American War. France because they wanted to keep the Mexican Empire aloft, but the UK had no need to keep aiding the CSA.

That, or have the Union keep fighting the South, and crush Lee. (Forcing Lee to lose control of Philadelphia.)

FanOfHistory

Banned

Yeah, TL 191 UK really screwed upYeah, all it did long term was make a permanent enemy of a strong nation that cost them Canada and anchored to an alliance with a weak state.

The UK most of all. Honesty, they had no real reason to aid the South in the Second Mexican-American War. France because they wanted to keep the Mexican Empire aloft, but the UK had no need to keep aiding the CSA.

That, or have the Union keep fighting the South, and crush Lee. (Forcing Lee to lose control of Philadelphia.)

The only reason they did was because the CSA promised to end slavery, and they wanted a counterweight to the USA. You have to remember that the close relationship we have with the UK today wasn't really developed until after WWI solidified in WWII. What the UK never expected was for Germany to become a major player in global politics.

The only reason they did was because the CSA promised to end slavery, and they wanted a counterweight to the USA. You have to remember that the close relationship we have with the UK today wasn't really developed until after WWI solidified in WWII. What the UK never expected was for Germany to become a major player in global politics.

Wasn't there an conversation between Kimball and an British Officer, and it basically outline how much of a embarrassment the CSA was to the UK and being 'allies' with the Confederate States? I understand the British wanting an counterweight, but I would think London would see America as the stronger of the two. (And given Germany had already been form and was already a rising star.)

Wasn't there an conversation between Kimball and an British Officer, and it basically outline how much of a embarrassment the CSA was to the UK and being 'allies' with the Confederate States? I understand the British wanting an counterweight, but I would think London would see America as the stronger of the two. (And given Germany had already been form and was already a rising star.)

Just because an officer says something, doesn't mean that is the general consensus of the leadership. During OTL WWI, many of the American people were supportive of the Central Powers because of the large number of people who had come to the US from those nations. It was the American leadership and big businesses who wanted to side with the Entente. It is possible that the UK was the same way when it came to the CSA. The leadership seeing them as a necessary ally to counter the USA since they would have to deal with Germany.

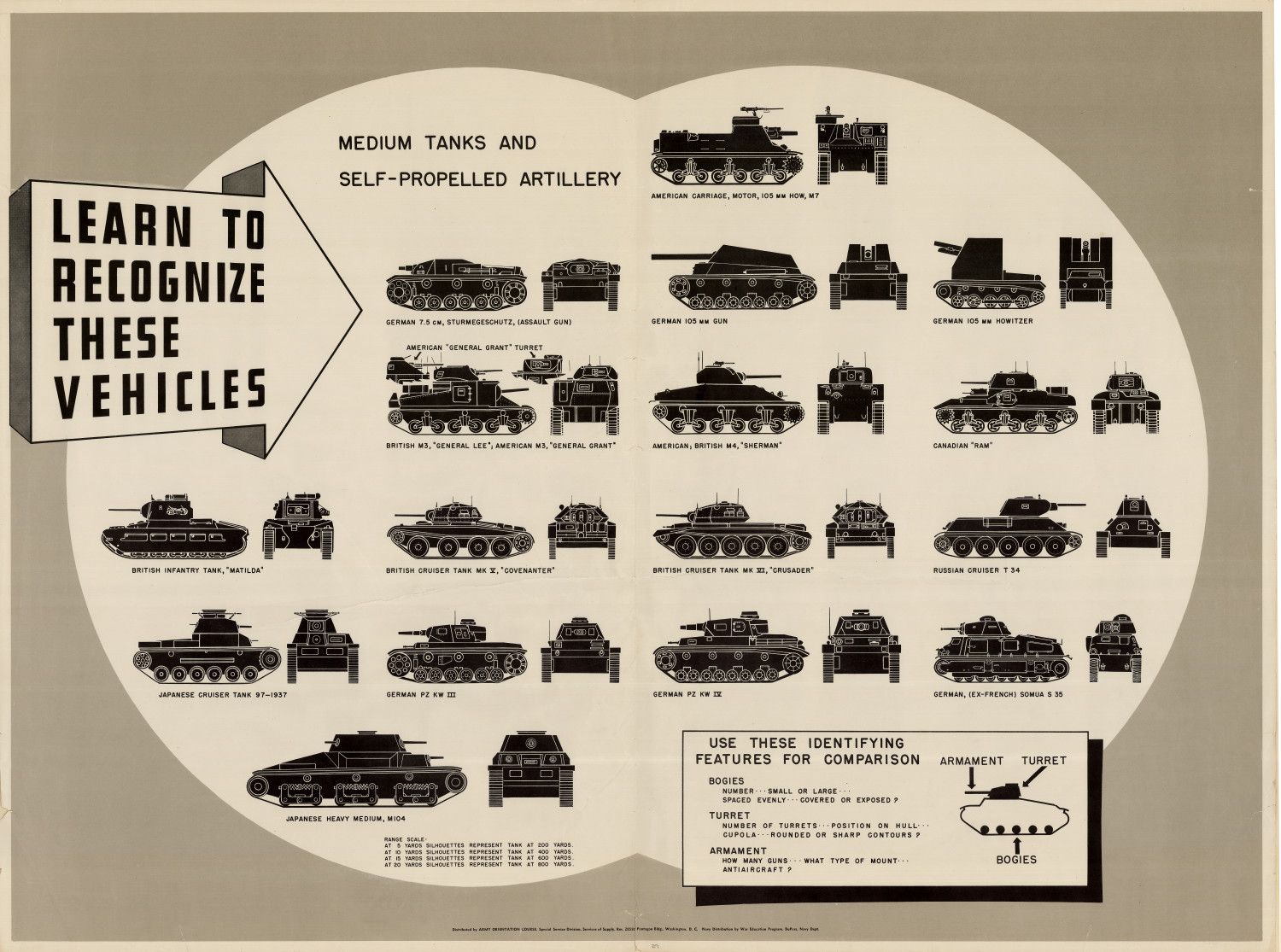

I'm wondering if a chart for various Second Great War barrels similar to this. Meant to show the soldiers what types of medium barrels and mobile artillery to expect.

Are there British and Russian AFV's on it then because the CSA used them and they didn't want them falling victim to friendly fire?I'm wondering if a chart for various Second Great War barrels similar to this. Meant to show the soldiers what types of medium barrels and mobile artillery to expect.

View attachment 432416

And why would there be a Japanese tank on there?

It's more of a general idea I was thinking of for a potential commission. Obviously the British and Russian vehicles could be replaced by Quebecois and Mexican, while the Japanese armor could remain as a left over from the Pacific War.Are there British and Russian AFV's on it then because the CSA used them and they didn't want them falling victim to friendly fire?

And why would there be a Japanese tank on there?

I see but I could see the CS using Brit and Russian designs and the need to be able to identify them.It's more of a general idea I was thinking of for a potential commission. Obviously the British and Russian vehicles could be replaced by Quebecois and Mexican, while the Japanese armor could remain as a left over from the Pacific War.

Good call.I see but I could see the CS using Brit and Russian designs and the need to be able to identify them.

Did the British ever try to retake their old Caribbean territories during the Second Great War? Also did the United States ever take French Guiana?

Share: