You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

One Nation Under the Southern Cross - an alternate Brazil TL (updated 13/08)

- Thread starter Ricard (i.e. Rdffigueira)

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 53 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

25. The Atlantic War (Pt. 4) (1830-1831) 25. The Atlantic War (pt. 5) (1831) 25. The Atlantic War (pt. 6) (1831-1832) 26. Regarding the Guianas... Interlude 3. The Colonial Wars of the 1830's Interlude 4. Not a Pretty Picture (1841-1847) 27. The Concert of Cartagena de Índias (1840) 28. 1831's Presidential ElectionIndeed, but in this case, the Portuguese only attack because they believe that Brazil is fragile. Don't worry, in the next post I'll give a more detailed background of the conflict.

25. The Atlantic War (pt. 1) (1828-1830)

1. The State of Portugal after the Brazilian War of Independence

His reign had witnessed the nadir of Portuguese fortunes, much like that of his brother-in-law, King Fernando VII of Spain, had contemplated the ruin of Spain. After the vicissitudes of the Iberian War, in which Portugal was occupied by the Spaniards, and had its naval force obliterated by the British Royal Navy, culminating with the destruction of a large part of the fleet and the “kidnapping” of the remaining ships, the restored Portuguese government had devised the “Revitalização” policy as an absolutely desperate attempt of recovering from the ruin and attempting to jumpstart a modernization of the nation, all at the same time they tried to quench the revolutionary sentiments in both Portugal and Portuguese America.

Now that Brazil became independent, however, Portugal had suffered an irrecoverable blow. Its economy was in shambles, considering that almost the whole of the exports from the metropolis went to the former colony, and it profited from the transition of Brazilian goods into the European markets; the colonies in Africa and India were too underdeveloped to yield the necessary financial bounties to recover the economy, and, even worse, the most profitable enterprise of the Portuguese Empire – slave trafficking – was suddenly terminated by the British. Whatever money it gained was necessary to rebuild the destroyed ports, like Lisboa itself, and modernize the army and rebuild the navy, a herculean effort for such a tiny and exhausted princedom.

Yet, much like a dog spanked by its cruel owner that is forced to return to him out of sheer hunger, the Crown of Portugal went to great lenghts to restore its centuries-old alliance with Great Britain. Whatever grudges they held toward “Perfidious Albion”, they must be swallowed, for the British were poised to be the rulers of the world, now that the stars of France and Spain had dwindled, for even the combined might of the stalwart Prussians and the vigorous Russians could do little to curb the ruler of the waves, which seemed apparently delegated to Britannia by Neptune himself.

Therefore, Portugal relented and humiliated itself, but their fortunes could only rise again if they successfully regained Britain as its godfather in Europe. Investments coming from London were the ones that facilitated the reconstruction of Lisboa and Porto, while British officers - veterans from wars in the Americas, in Europe and in Asia - arrived to instruct the green recruits, and the instable market of Portugal again received much necessary British commodities. Of course, the British government had long since realized that even if broken, Portugal could still be harnessed as a valuable asset, if not on the European geopolitics, at least in Africa and Asia. The prosperity of its colonial empire would preserve a convenient network of transport, communication and commerce through the Atlantic, the Indian and even the Pacific Oceans, something that interest Britain very much.

******

King João VI’s successor was his eldest son, D. Pedro de Bragança, who was crowned as King Pedro IV of Portugal and Algarves. The new monarch was young, very ambitious and driven by a strong personality, unlike his phlegmatic predecessor. He was fully aware of the social, political and economic state of the Portuguese Empire, having been acting as a de facto regent while his father wasted his miserable existence in palatine idylls. King Pedro IV was determined to jumpstart the recovery of the empire, and, as a tour de force, during his first years as a crowned prince, he immediately set out important reforms, in an attempt to “modernize” the court, the society, the military and the colonial administration.

Coronation ceremony of King Pedro IV of Portugal and Algarves

With the end of the Iberian War and the restoration of the Braganças from their exile in Madrid, the conservative faction that had been grudgingly kissing the boots of the British military officers regained its full power, and represented a particularly retrograde ideology, based on the old fashioned premise that the King exerted his power over the Empire by a God-given authority, assisted by a privileged aristocracy. This cabal of noblemen, in fact, had been pointed out as the main culprit of the Brazilian Revolution and the following military disaster, as they outright refused any kind of compromise with the exasperated Brazilian subjects, on the grounds that any kind of undue liberties would invite the infestation of revolutionary allegiances (which they called "francesias" in Portugal).

King Pedro IV of Portugal was fully aware of this, and, unlike his father, desired a more conscientious faction on his side to govern the decaying empire. The young monarch quickly associated himself with the moderates, those who favored an alliance with Britain out of pure pragmatism, and also supported reforms in the homeland and in the colonies, but also made a point to get the growing liberal coalition on his side.

For these reasons D. Pedro and his Ministers took the initiative of drafting a Constitution for Portugal. The Cortes of Lisboa had gained a lot of power in the restored Bragança government, having won a more decisive voice in the decision-making of the empire, but their main request, a Constitution to limit monarchical power, had been constantly delayed by King João VI – who, in fact, simply spirited away to his palace of Queluz and left the administration in the hands of his son and his Ministers.

Now, D. Pedro, already in his capacity as a regent during his father’s constant periods of illness, had already promised to draft a Constitution to appease the irritated factions inside the Cortes. For a time, he even had imagined that a coalition between the conservatives and moderates might obstruct the debates, but as soon as he realized that the clear majority of the representatives of the Cortes desired a Constitution, he decided to get ahead of his opponents, lest his government might be victim of a revolution or insurrections.

Thus, already in the year of 1828, he proposed to the Cortes a text of principles and rules, clearly inspired in the Russian Constitution of 1818 [1], to restructure the government and provided a charter of fundamental rights for its citizens, all while securing substantial powers for the Crown.

Another successful policy was the Integracionismo (lit. "Integrationism"), a series of reforms to devolve more political and decision-making powers to the white elites of the African, Indian and Oceanian colonies, as well as to modernize their armies and gradually assimilate the “subject populations”, especially in Angola, Moçambique and Nova Guiné.

King Pedro IV would sponsor a series of military expeditions to expand the Portuguese domain in southern Africa, and even initiated ventures into the Omani domain of Zanzibar and in Kongo, which would be continued by his successors. Much like the British Empire had turned their attentions to India after the loss of the North-American Thirteen Colonies, and the Spanish Empire had began to focus on Mexico, the Caribbean and eastern Asia after the collapse of its great commonwealth, so did Portugal finally abandoned its dreams of reconquering Brazil and decided to implement a greater focus on the colonization of the darkest continent.

King Pedro IV of Portugal was fully aware of this, and, unlike his father, desired a more conscientious faction on his side to govern the decaying empire. The young monarch quickly associated himself with the moderates, those who favored an alliance with Britain out of pure pragmatism, and also supported reforms in the homeland and in the colonies, but also made a point to get the growing liberal coalition on his side.

For these reasons D. Pedro and his Ministers took the initiative of drafting a Constitution for Portugal. The Cortes of Lisboa had gained a lot of power in the restored Bragança government, having won a more decisive voice in the decision-making of the empire, but their main request, a Constitution to limit monarchical power, had been constantly delayed by King João VI – who, in fact, simply spirited away to his palace of Queluz and left the administration in the hands of his son and his Ministers.

Now, D. Pedro, already in his capacity as a regent during his father’s constant periods of illness, had already promised to draft a Constitution to appease the irritated factions inside the Cortes. For a time, he even had imagined that a coalition between the conservatives and moderates might obstruct the debates, but as soon as he realized that the clear majority of the representatives of the Cortes desired a Constitution, he decided to get ahead of his opponents, lest his government might be victim of a revolution or insurrections.

Thus, already in the year of 1828, he proposed to the Cortes a text of principles and rules, clearly inspired in the Russian Constitution of 1818 [1], to restructure the government and provided a charter of fundamental rights for its citizens, all while securing substantial powers for the Crown.

Another successful policy was the Integracionismo (lit. "Integrationism"), a series of reforms to devolve more political and decision-making powers to the white elites of the African, Indian and Oceanian colonies, as well as to modernize their armies and gradually assimilate the “subject populations”, especially in Angola, Moçambique and Nova Guiné.

King Pedro IV would sponsor a series of military expeditions to expand the Portuguese domain in southern Africa, and even initiated ventures into the Omani domain of Zanzibar and in Kongo, which would be continued by his successors. Much like the British Empire had turned their attentions to India after the loss of the North-American Thirteen Colonies, and the Spanish Empire had began to focus on Mexico, the Caribbean and eastern Asia after the collapse of its great commonwealth, so did Portugal finally abandoned its dreams of reconquering Brazil and decided to implement a greater focus on the colonization of the darkest continent.

The most expensive project, however, was the reconstruction of the warfleet. The backbone of the Navy continued to be the old vessels from the times of the British attack, the same ones that had been sent to Brazil and from there to the Caribbean to conduct naval operations against the enemies of the United Kingdom during the Napoleonic Wars. D. Pedro knew that new ships of the line would be too dispendious, and made a bold move to invest in lighter and speedier warships.

Substantial loans were taken from the British and Dutch banks, while massive quantities of wood, iron and other raw materials were extracted from Angola and Kongo; the trafficking of slaves across the sea had been forbidden by royal decree, but the commerce and exploitation of forced labor was unaffected inside the colonies, and Portugal had plenty of supply from the interior of Africa.

Even if the Portuguese fleet might never reach the prestigious position it had during the epoch of Vasco da Gama and Bartolomeu Dias, D. Pedro had resolved to see it restored to a maritime force to be reckoned with, much like Spain and Netherlands.

_________________________________________

[1] The so-called “Russian Constitutionalism”, created during the regime of Tsar Alexander I of Russia, would inspire a whole generation of constitutional diplomas during the 19th Century, by its virtue of conciliating the pretentions of more liberal ideologues with a strong position of the sovereign in the affairs of the nation, unliked Britain and France, for example. On one hand, there were elective assemblies for lawmaking, but, on the other hand, the monarch remained as the president of the congress, among other idiosyncrasies that, despite being so fitting for the oriental despotism of the Tsar, were also welcomed by the Kaiser of Prussia, and later by the Emperor of Austria and by the King of Spain, whose monarchs had no intention of being amputated of their centuries-old prerrogatives. Like it would be pointed out by Sir Arthur Wellesley, a couple years later: "Russian Constitucionalism is nothing more than a watered-down tyranny".Substantial loans were taken from the British and Dutch banks, while massive quantities of wood, iron and other raw materials were extracted from Angola and Kongo; the trafficking of slaves across the sea had been forbidden by royal decree, but the commerce and exploitation of forced labor was unaffected inside the colonies, and Portugal had plenty of supply from the interior of Africa.

Even if the Portuguese fleet might never reach the prestigious position it had during the epoch of Vasco da Gama and Bartolomeu Dias, D. Pedro had resolved to see it restored to a maritime force to be reckoned with, much like Spain and Netherlands.

_________________________________________

Last edited:

Angola will be easier to meld than Mozambique, where thhe Portuguese presence and the thinly Portuguese prazeiros were at an absolute nadir.

Hope Portugal can get the Pink Map or Congo at the least; Portuguese coulld have easily had a headstart on African exploration, and had sent men to the interior before by way of the Zambezi.

Having Pedro IV as king will be a huge boon, IMO. Like a crowned Pombal, albeit with a romantic streak

Hope Portugal can get the Pink Map or Congo at the least; Portuguese coulld have easily had a headstart on African exploration, and had sent men to the interior before by way of the Zambezi.

Having Pedro IV as king will be a huge boon, IMO. Like a crowned Pombal, albeit with a romantic streak

Angola will be easier to meld than Mozambique, where thhe Portuguese presence and the thinly Portuguese prazeiros were at an absolute nadir. Hope Portugal can get the Pink Map or Congo at the least; Portuguese coulld have easily had a headstart on African exploration, and had sent men to the interior before by way of the Zambezi. Having Pedro IV as king will be a huge boon, IMO. Like a crowned Pombal, albeit with a romantic streak

Indeed, Angola has a bigger chance of becoming what Algeria became for France than distant Moçambique, but you are absolutely correct, there will certainly be a drive towards connecting the two colonies into a single territory, and thus we likely get the Pink Map that the British were so keen on "cockblocking" in OTL. Regarding Kongo, Portugal indeed had a presence there since the 16th Century (indeed, it was due to their influence that Congo accepted Christianity), but I can already anticipate that the Portuguese penetration will be much like the French intervention in Madagascar.

I didn't know particularly about the Zambezi exploration that you mentioned. I went to research it, and found it a very interesting tidbit of information. I'll be sure to work Portugal's expansion into Africa taking this circumstance into account, thank you very much, @St. Just.

D. Pedro ITTL will be able to do more for Portugal than he did for both Brazil and Portugal IOTL, considering that the all the major crisis of his reign derived from his blundered attempt of securing both Brazilian and Portuguese crowns. This means that the destructive civil war against his brother Miguel will be entirely butterflied away, and, yes, Portugal will be able to devote its energies and resources in modernizing the metropolis and expanding the colonial empire. This won't necessarily be easy, as the Netherlands has its own designs in Oceania that might thwart Portuguese approaches, and Britain sooner or later might grow weary of Portuguese adventures.

Oh, and wait for D. Pedro II

Indeed, Angola has a bigger chance of becoming what Algeria became for France than distant Moçambique, but you are absolutely correct, there will certainly be a drive towards connecting the two colonies into a single territory, and thus we likely get the Pink Map that the British were so keen on "cockblocking" in OTL. Regarding Kongo, Portugal indeed had a presence there since the 16th Century (indeed, it was due to their influence that Congo accepted Christianity), but I can already anticipate that the Portuguese penetration will be much like the French intervention in Madagascar.

I didn't know particularly about the Zambezi exploration that you mentioned. I went to research it, and found it a very interesting tidbit of information. I'll be sure to work Portugal's expansion into Africa taking this circumstance into account, thank you very much, @St. Just.

D. Pedro ITTL will be able to do more for Portugal than he did for both Brazil and Portugal IOTL, considering that the all the major crisis of his reign derived from his blundered attempt of securing both Brazilian and Portuguese crowns. This means that the destructive civil war against his brother Miguel will be entirely butterflied away, and, yes, Portugal will be able to devote its energies and resources in modernizing the metropolis and expanding the colonial empire. This won't necessarily be easy, as the Netherlands has its own designs in Oceania that might thwart Portuguese approaches, and Britain sooner or later might grow weary of Portuguese adventures.

Oh, and wait for D. Pedro II

Actually, perversely, Mozambique is definitely better for Algerianization. There was more farmland to the south (aka Zimbabwe) and minerals to the north; Angola has always been inhospitable, and native Africans had to constantly bail out the criminals Portugal sent to Angola as settlers (the degredados). If you need any more info on the prazeiros of Mozambique I have sources and whatnot. Weirdest colony of all time IMO.

And Pedro I plus Pedro II will definitely be good for Portugal.

Actually, perversely, Mozambique is definitely better for Algerianization. There was more farmland to the south (aka Zimbabwe) and minerals to the north; Angola has always been inhospitable, and native Africans had to constantly bail out the criminals Portugal sent to Angola as settlers (the degredados). If you need any more info on the prazeiros of Mozambique I have sources and whatnot. Weirdest colony of all time IMO.

And Pedro I plus Pedro II will definitely be good for Portugal.

I'd like these sources you said. This will be very helpful, as I have little knowledge of Sub-Saharan Africa before the Scramble. Only some bits about Mali, Sokoto and Dahomey, and that's it; of course, what I enjoy the most about writing this stuff is having a good chance of researching more about History, Geography, Politics, and so forth. Thanks in advance!!

25. The Atlantic War (pt. 2) (1829-1830)

2. The "Cruzada Libertadora"

King Pedro IV desired a show of force in the international geopolitical arena to restore Portugal’s reputation and affirm to the great powers, especially Great Britain, Prussia and Russia, that it desired to return to its due place in the sun as a world empire.

Starting in 1829, the newest frigates from the homeland began operating in the African coast, patrolling it from Senegal to the Cape of Good Hope, and from there all the way to Somalia. The aim of the Royal Portuguese Armada was to curb the Atlantic commerce, once and for all, and the British, likely amused by what they must be interpreting as a tiny dog barking loud to gain attention, supported the initiative, and became more accepting of alliance overtures coming from Lisboa. This policy became known as “Cruzada Libertadora” (lit. “manumission crusade”) as it intended to capture slaver ships operating in the Atlantic Sea and release the imprisoned Africans back to their homelands.

By 1830, almost the whole of the western nations had abolished the importing of enslaved workforce from Africa. In some countries, such as in La Plata and Nueva Granada, this was soon followed by outright emancipation of slaves inside their countries, while in others, such as the United States of America and in Spanish Nueva España, captivity remained in force, even if the acquisition from overseas had been forbidden. Indeed, the USA, Spain and Brazil were, in this very order, the last countries to outlaw slave trade in the occident.

In Brazil, however, this was not fulfilled by a law approved by the Parliament, but rather from an Executive fiat, that is, President Mena Barreto’s decree to “regulate matters related to merchant ships”, and caused almost universal rejection by the Legislative and by the States. Inácio Joaquim Monteiro, even before his election, had vowed to take down Mena Barreto’s “tyrannical” act, and propose a joint discussion with the Parliament and the State Governorates about the slave trafficking question.

Between Mena Barreto and Joaquim Monteiro’s terms, then, slave trafficking was resumed earnestly in Brazil, and, in fact, it experienced a sudden growth, as slave traders, perhaps fearing the inevitable extinction of their “honest jobs”, made enormous investments to bring the largest possible numbers of captives, especially nubile women, so as to multiply the profitability of these “long-term transactions”.

In 1829, almost all ships that voyaged to Africa to acquire captives were Brazilian, and, indeed, almost all of these were civilian transports, with but an insignificant number of illegal Spanish flotillas doing the same. Portugal was aware of this, and it soon became clear that their Cruzada Libertadora was but a very convenient excuse to target vessels carrying the Brazilian flag.

The Portuguese sailors also had literally centuries of navigation experience ahead of the Brazilian voyagers, and were too familiar with the transport lines (including islands and coasts necessary to resupply) going from the Americas to Africa. To target and capture Brazilian ships was but an easy task, especially considering that the slaver crews, out of domestic competition between their investors, rarely operated in groups. In fact, the first appearance of sea convoys happened in early 1830, but even this proved to be a vain effort, as the Portuguese patrol ships were all military-grade. In opposition, Brazil had a negligible navy, and none of the armed ships went far away from the littoral.

In a matter of months, the Royal Portuguese Armada intercepted an impressive number of Brazilian ships, and, indeed, many of them were actually merchant ships that had no part in slave commerce. It became soon clear that Portugal was exacting its petty revenge by obstruction Atlantic commerce by Brazilian ships. Due to the geopolitical position of the Portuguese colonies, however, this also meant that trade with Arabia, India and Oceania were also curbed, as the Brazilian crews had little success in escaping the blockade between Moçambique and Madagascar, where the British ships also operated against slavers. Rumors began to appear, in fact, that innocent civilian ships had been sunken without warning shots, while others were captured and their crews were imprisoned and shipped off to Goa – these were never confirmed, of course, and the Portuguese Crown denied every accusation, affirming that they only targeted naval groups suspect of carrying slaves.

By early 1830, the Brazilian markets were already suffering the detrimental effects of the Cruzada Libertadora, with the Atlantic and Indian Oceans effectively off limits. These markets were still flooded with British imports – and thus Perfidious Albion kept profiting from the ruin of the Brazilians – but the British government, even despite the protests of the Brazilian embassy in London, feigned blindness to Portugal’s bullying. After a formal complaint from the Brazilian Presidency itself, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom brashly retorted that slave commerce would come to an end, one way or another.

*****

President Inácio Joaquim Monteiro in 1830 was facing the crisis resulting from the Rio Grande do Norte scandal and also the insurrections caused by the census’ data collection. The last thing he wanted was a foreign war against a European power – even if he personally still harbored a serious hatred towards Portugal – and in conditions that they might suffer, considering that Brazil still lacked a Navy. In fact, his political opponents now screamed loudly in the podium of the Parliament’s Hall of Debates, the President had discontinued his predecessor’s ambitious project to construct a fleet and, perhaps, transform Brazil into a naval power. Nevertheless, despite his hesitation, the popular outburst favored a war.

“Brazil must invade Portugal!” a newspaper headline read in bold letters, and many other editorials were of same opinion, as were State Governors who sent representatives and letters to the President, and many Members of the Parliament, especially the military officers. Even Mena Barreto himself wrote to the President, laconically explaining that, as a marshal, he was still willing and able to serve the nation in the event of a war, but was solemnly ignored by Joaquim Monteiro.

The President only took his decision after he received the confirmation that the southern borders were secure – despite his opposition to many of President Mena Barreto’s policies, he had entirely supported the war in Banda Oriental, and its annexation (due to the fact that goods from the region supplied the markets of São Paulo) – having placed men of his trust in the command of the 2nd and 3rd Brazilian Corps, respectively quartered in Rio Grande do Sul and in Banda Oriental. President Joaquim Monteiro was no strategist, but he had every reason to fear that, if Brazil became embroiled in an external war, La Plata could grab the perfect opportunity to attempt a reconquest of Southern Brazil.

It was already the month of August 1830 when President Inácio Joaquim Monteiro issued a declaration of war against the Kingdom of Portugal, listing as casus belli a series of systematic attacks against civilian ships in the Atlantic Sea.

What the President did not know, however, was that Portugal had already played its card in a preemptive strike against the Brazilian mainland, and, even before the official correspondence from the Rio de Janeiro government arrived in Lisboa, two separate fleets had already departed from the Açores.

Their mission: to capture and secure the Guianas, and to join forces with a separatist faction centered in Pernambuco, which intended to spark a secession of the Northeastern States from the Republic of Brazil.

Last edited:

A war to preserve slavery. Gee, I wonder how that's ever worked out. Especially since Britain is def not on your side.

Brazil is operating in deep waters, but so are the Portuguese (...and not just literally). I don't think either one is going to have a great time with this war!

Also, and this is just a little suggestion, but I think the "literal" translation would be more likely to be "freedom crusade" than "manumission crusade". It has the same meaning in English (freeing a slave = manumitting a slave) but it's more...how you say..."popular," in the sense of being closer to how people actually speak.

Also, and this is just a little suggestion, but I think the "literal" translation would be more likely to be "freedom crusade" than "manumission crusade". It has the same meaning in English (freeing a slave = manumitting a slave) but it's more...how you say..."popular," in the sense of being closer to how people actually speak.

Deleted member 67076

Whoa, abolishing the Atlantic slave trade by 1830 has massive economic and cultural effects on Cuba and West Africa. Most of Cubas slaves were imported in this final century, and the distinctive Afro bent to Cuban culture is largely Yoruba for a reason. Here, that's prevented.

So that means the population of Yorubaland is going to be massively larger (an extra 2 million or so) and so will be in a much better position to resist Sokoto (but on the other hand, Sokoto's plantations will have a much larger labor force). As well, Dahomey and Togo will be suffering economic collapse with the end of the slave trade given that was their primary source of income.

Really the whole map of West Africa is gonna have to be redrawn from this.

And of course, Brazil will need to shift their source of labor for sugar plantations (although they could always contract labors from west Africa).

So that means the population of Yorubaland is going to be massively larger (an extra 2 million or so) and so will be in a much better position to resist Sokoto (but on the other hand, Sokoto's plantations will have a much larger labor force). As well, Dahomey and Togo will be suffering economic collapse with the end of the slave trade given that was their primary source of income.

Really the whole map of West Africa is gonna have to be redrawn from this.

And of course, Brazil will need to shift their source of labor for sugar plantations (although they could always contract labors from west Africa).

A war to preserve slavery. Gee, I wonder how that's ever worked out. Especially since Britain is def not on your side.

Indeed, the guys from the CSA should give some lectures in Brazil to explain how this sort of thing usually doesn't works.

Britain will not support Brazil, but neither will intervene directly in the war. Considering that Portugal still lacks the manpower to attempt a "recolonization" of any kind, it will invest more in naval and coastal attacks, while Brazil still lacks significant sea-wide power projection, this war will be a rather low-key affair.

Brazil is operating in deep waters, but so are the Portuguese (...and not just literally). I don't think either one is going to have a great time with this war! Also, and this is just a little suggestion, but I think the "literal" translation would be more likely to be "freedom crusade" than "manumission crusade". It has the same meaning in English (freeing a slave = manumitting a slave) but it's more...how you say..."popular," in the sense of being closer to how people actually speak.

Portugal is actually being extremely realistic. They don't really have a substantial infantry force to attempt a comprehensive land invasion, so their goals are short-term and limited, as you'll see. This, in fact, might suffice, because the political and economic situation in Brazil will prevent a more coordinated effort to expel the Portuguese, and, in this time, indeed, they had no foreign support.

Regarding the translation, I agree with your point, "freedom crusade" is much more fashionable. I just prefered "manumission" because it's a term more associated with slavery itself, and wanted to picture it differerently from the "let's spread freedom" arguments that we have seen in some wars during the 20th Century.

Whoa, abolishing the Atlantic slave trade by 1830 has massive economic and cultural effects on Cuba and West Africa. Most of Cubas slaves were imported in this final century, and the distinctive Afro bent to Cuban culture is largely Yoruba for a reason. Here, that's prevented. So that means the population of Yorubaland is going to be massively larger (an extra 2 million or so) and so will be in a much better position to resist Sokoto (but on the other hand, Sokoto's plantations will have a much larger labor force). As well, Dahomey and Togo will be suffering economic collapse with the end of the slave trade given that was their primary source of income. Really the whole map of West Africa is gonna have to be redrawn from this. And of course, Brazil will need to shift their source of labor for sugar plantations (although they could always contract labors from west Africa).

Again, I must thank you for helping here. Considering I try to focus more on Brazil itself, I sometimes lack consideration towards the medium and long term impacts of some butterflies around the world. West African countries, in this regard, are ones that I'd probably have missed. I'll be sure, then, to study more about the situation in the region around Sokoto in the case I address the butterflies occurring in the region.

What I can say about Brazil is that slave labor will persist for a time - considering that slavery itself will still be legal - but the panorama will drastically change when the (yet still in infancy) abolitionist movements gain more force.

Well, but isn't that exactly what Portugal is doing? At least the early 19th century version of it, anyway.Regarding the translation, I agree with your point, "freedom crusade" is much more fashionable. I just prefered "manumission" because it's a term more associated with slavery itself, and wanted to picture it differerently from the "let's spread freedom" arguments that we have seen in some wars during the 20th Century.

Deleted member 67076

You're welcome. A little word of warning; it gets really, really hard to track down all the developments outside the world in great detail, so the focus on the central topic is always better than being overwhelmed by the rest of the world.Again, I must thank you for helping here. Considering I try to focus more on Brazil itself, I sometimes lack consideration towards the medium and long term impacts of some butterflies around the world. West African countries, in this regard, are ones that I'd probably have missed. I'll be sure, then, to study more about the situation in the region around Sokoto in the case I address the butterflies occurring in the region.

What I can say about Brazil is that slave labor will persist for a time - considering that slavery itself will still be legal - but the panorama will drastically change when the (yet still in infancy) abolitionist movements gain more force.

But of course, keeping tabs on how the world has changed is good.

I'm excited to see abolition movements pick up steam early on. Wonder if this means we'll get an earlier Law of Free Birth.

It has been a while since the previous update, but now I've finally got some free time, enough to put some new chapters online and, at last, reward my friends who committed themselves to read about this alt!Brazil. In the least, I intend to finish the chapters related to the Atlantic War, since I absolutely hate leaving untied knots in stories.

A short summary for those who might perhaps be picking up by reading this post:

In the previous installment we had a very unexpected escalation of hostilities between Portugal and Brazil. The former metropolis, which for so many centuries drained Africa of its lives to sweat and bleed in the American plantations, now championed the anti-slave trafficking cause as a means of appeasing Britain and thwarting the designs of the fledgling Brazilian Republic in the Atlantic, launching a series of coordinated attacks against Brazilian ships.

Brazil responds by declaring war against Portugal, but, despite its humongous size, worthy of the unironic appelation of the "empire of the tropics", the young republic is still recovering from a victorious but ill-conceived and very costly military adventure in the Platean border, and suffering with separatist movements (most notably in the Northeastern Region) that, yet again, threaten to tear this loosening fabric apart. In this context, the incumbent President of the Federation, Joaquim Inácio Monteiro, is experiencing his own tribulations in the complicated political arena, and has yet to prove to be the right man to face the crisis.

A short summary for those who might perhaps be picking up by reading this post:

In the previous installment we had a very unexpected escalation of hostilities between Portugal and Brazil. The former metropolis, which for so many centuries drained Africa of its lives to sweat and bleed in the American plantations, now championed the anti-slave trafficking cause as a means of appeasing Britain and thwarting the designs of the fledgling Brazilian Republic in the Atlantic, launching a series of coordinated attacks against Brazilian ships.

Brazil responds by declaring war against Portugal, but, despite its humongous size, worthy of the unironic appelation of the "empire of the tropics", the young republic is still recovering from a victorious but ill-conceived and very costly military adventure in the Platean border, and suffering with separatist movements (most notably in the Northeastern Region) that, yet again, threaten to tear this loosening fabric apart. In this context, the incumbent President of the Federation, Joaquim Inácio Monteiro, is experiencing his own tribulations in the complicated political arena, and has yet to prove to be the right man to face the crisis.

25. The Atlantic War (Pt. 3) (1830)

3. A Sedição Pernambucana (Pernambuco’s Conspiracy)

To this day, scholars still debate the nature and the extent of the so-called Sedição Pernambucana, a separatist movement that gained strength in Recife and other regions of the Northeast Brazil. While the more romantic analysts take as granted that the whole of the Northeast yearned to break off the Republic of Brazil (a picture that became prevalent due to the modern fictional portrayals of the Atlantic War in audiovisual and literary media, extremely popular in the 50's), nowadays the scholar circles sustain that outright emancipation was the desire of a small, albeit influential minority, influenced by liberal (even if not democratic) ideas.

In any event, there was no serious drive towards a reincorporation of the Northeast into the Portuguese Empire as a colony, as many would affirm in the following decades (including Inácio Joaquim Monteiro’s own Ministers), but simply a convenient alliance with Portugal to destabilize the government in Rio de Janeiro if it failed to accept the ultimatum of independence. The rebel regime actually sought a greater diplomatic approximation with the United States of America and with Nueva Granada than Portugal itself.

Popular terminology nothwithstanding, the insurrection was not limited to Pernambuco, but, on the contrary, it had as its epicenter the cities of Recife and Olinda – while the backcountry, the districts laying in the valley of the River São Francisco, there was no official adhesion to the rebellion – and quickly gained the support of liberal and radical factions in Alagoas, Parahyba, Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará and northern Bahia, thus encompassing a large part of the Northeast.

Demonstrating the complexity of sociopolitical trends and developments in early republican Brazil, the Sedição Pernambucana is actually an umbrella term to designate a provisory alliance between various political and social groups dissatisfied with the policies and actions of the Federal Government in Rio de Janeiro. The most radical of these factions were the separatists (mainly from eastern Pernambuco, Alagoas and Parahyba), but there were moderates and liberals (mainly the middle urban classes of littoral Bahia and Ceará), whose main aim was to obtain more favorable concessions from the government, such as tax privileges, financial benefits and greater representation in the domestic politics, owing to their economic and demographic weight in comparison to the States of the Southeast and South. By the time, they were only amalgamated in their common repudiation of Inácio Joaquim Monteiro’s regime, especially after the Rio Grande do Norte scandal.

*****

The movement threatened to spark into a genuine emancipation war after some more radical representatives, coming from the educated elite of Recife, sent agents to Lisboa, proudly announcing their conditions to broker an alliance with Portugal against their “common enemies”.

King Pedro IV was savvy and eagerly took advantage of the opportunity, even if the separatists repeatedly affirmed their disinterest in rejoining the Portuguese colonial empire, and rediscussed with his ministers the grand strategy against the republican government of Brazil.

The information brought by the Brazilian traitors to the court in Lisboa were decisive to make the Portuguese government quickly shift from a simple policy of commercial blockade to a cautious, but dedicated amphibious military invasion. So far, the Portuguese had not been aware about the precarious situation of the Brazilian Navy, and had, in fact, been operating solely in the African western coast, so as to attract whatever Brazilian warships out of their own safe zone.

Now, realizing they had an obvious advantage (at least in sea), and seeking to capitalize on the internal fracturing of the republican government – alas, the humongous nation of Brazil would collapse under its own weight, much like the former colonies of Spain – decided to launch the available warships of Africa to the northern Brazilian coast.

The strategy conjured by the Lusitanian King’s War Cabinet consisted of the following steps:

- One of the fleets – the Armada d’Angola – would capture the archipelago of Fernão de Loronha [OTL Fernando de Noronha] off the coast of Rio Grande do Norte, to serve as the base of operations in the western Atlantic, forming a direct line of communication and transport between Brazil and Cabo Verde.

- Two regiments of marines coming from Angola would disembark in Recife to assist the separatist rebels in their civil war against the government in Rio de Janeiro. In any event, this military force would not be committed in battles against the Brazilian forces until second orders. Their purpose would be solely to create a diversion;

- The main goal of the Portuguese was the reconquest of the Guianas, conducted by the Armada dos Açores. It was, after all, the only territory to which the Portuguese still claimed some (de jure) legitimacy, having been recognized by the Congress of Vienna itself, and also by the British government. Its geostrategic position would facilitate the capture, as it had but a few federal forces, and was too distant from any of the main centers of power in Brazil to receive reinforcements quickly.

- Once the Guianas had been secured, Portugal would attempt to expand the conquest over stretches of Grão-Pará, especially Belém. With luck, these remote regions would spontaneously desire a return to the Portuguese empire, or either would be bargaining chips to force the Rio de Janeiro regime to accept the surrender of the Guianas.

4. The arrival of the Portuguese in Pernambuco

Portugal in multiple attempts had tried to convince Great Britain to join the war, but the British haughtly rebuffed their diplomatic pleas. The British ambassador in Lisboa - Sir Thomas Gaye, 2nd Baron of Sheffield - impetuously argued that Westminster held no ill disposition towards Brazil, even in spite of the "slavery question", and that Portugal would do well to not disrupt Albion's interests in South America.

King Pedro IV was no fool, and, despite his inflamed rhetoric to bolster his troops’ morale and to cement union among his subjects against a foreign adversary, he knew that Portugal could not hope, without British support, for anything else than some scraps of tropical territories in the Americas and, with some luck, for a convenient speeding-up of what they believed would be an inevitable breakup of the former Portuguese America, opening new venues for intervention south of the Equator.

At the time, the Brazilian government had no reasons to expect a maritime invasion, even if they feared coastal attacks out of the lack of patrolling forces in the Atlantic littoral, so the main standing armies remained stationed in their regular positions: the 1st Brazilian Corps in Rio de Janeiro, the 2nd Corps in Banda Oriental, the 3rd Corps in Rio Grande do Sul, the 4th Corps in Piauhy and the 5th Corps (a much smaller force of recruits levied by President Mena Barreto in 1827) in Matto Grosso, with minor garrisons in border outposts of the Guianas and Grão-Pará.

The Presidency invested its resources and energy in resuming Mena Barreto’s defunct fleet-building project, and a total of twelve ships in the ports of Santos (São Paulo), Rio de Janeiro and Vitória (both in the State of Rio de Janeiro) and Salvador (Bahia), focusing on Indiamans and frigates. Besides, it issued letters of marque to whatever armed ships might want to participate on the war.

The most famous of these “modern privateers”, whose fame grew especially around the romantic legends of the 1950’s audiovisual media, was Frederik Carelszoon, a Dutch privateer who claimed to be a bastard son of Carel Hendrik Ver Huell, a Dutch-born admiral who had been employed in the service of France during the Napoleonic Wars, and also the same one who, according to some nasty rumors, had an affair with Queen Hortense de Beauharnais [1], wife of Louis Bonaparte, Napoléon’s brother, who had reigned as King of Holland. This would mean, then, that Frederik Carelszoon – whose most famous exploit would be the sack of a Portuguese citadel in the Açores in early 1832 – was supposedly (according to his own bold claims, at least) a patrilineal illegitimate half-brother of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the last robust representative of Bonapartism in France, and who would even attempt stage a failed coup attempt against King Louis-Phillipe I during the Second French Revolution (in 1844) [2]

*****

The Portuguese did not receive a warm welcome in Recife. Their fleet had captured Fernão de Loronha in a bloodless advance, and now the same ships that had allegedly sunken civilian Brazilian ships were stationed in uncomfortable proximity.

All but the youngest inhabitants of the Northeastern Brazil still remembered vividly the abuses and violence committed by Portuguese soldiers during the War of Independence, and, before that, the abuses and violence committed by the Portuguese colonial overseers. Besides, some of the divisions of the Portuguese army were actually made up of European mercenaries, mainly French soldiers who had found themselves without employment after the Napoleonic Wars, and thus had no fraternal sentiment towards the Luso-Brazilian former colonial subjects.

In fact, the coming of the Lusitanians created a brief fallout among the Brazilian factions that disputed the political fate of Pernambuco in 1830, as it had been the shady work of a small and radical group (more inclined towards monarchism) that had surreptitiously sent agents to Lisboa in the previous year to seek King Pedro IV’s help in their rebellion against the federal government. Most of the rebels, however, had no interest in a foreign intervention by Portugal (or Spain, for example), considering the old hatreds still enkindled in national consciousness.

One could say, in fact, that the universal hostility towards Portugal was the most reliable cement that had amalgamated the various political factions in Brazil during the War of Independence and some decades after it, the lusophobe sentiment was still persistent. As said before, the ones that sought foreign assistance favored approach to the United States of America or to Nueva Granada, nearby non-imperialist nations that would genuinely support the emancipationist cause.

________________________________

[1] There is indeed a secret (baseless) rumor that Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, who IOTL became Emperor Napoleon III, had actually been fathered by Carel Hendrik Ver Huell, the Dutch Admiral, in a secret affair with Queen Hortense.

As our brilliant fellow ALT-writer Lycaonpictus said once:"I include details like this to make my own ideas seem plausible by comparison".

[2] This is an analogue of the 1848 Revolution in France, and, similar to OTL, it results in the creation of a republic.

25. The Atlantic War (Pt. 4) (1830-1831)

5. An irrefutable offer

The so-called “Suassunas” [1] were the vanguard group in the separatist faction in Pernambuco, comprising moderates from the urban middle-class and wealthy landowners, who desired a union with Bahia and the neighboring states to join into a confederacy, simply named “Confederação de Pernambuco”. It was spearheaded by the influential Cavalcanti e Albuquerque family of Olinda coming from the sugar-mill named “Suassuna” (thus the name movement), and strongly influenced by the freemasonry and the ideas of the French Revolution.

They decided that help from Portugal would be a necessary evil, especially after they received reassurance from the King in Lisboa himself that the Crown of Portugal would not violate the “inalienable rights and liberties of the happy brothers of Portugal”, and that the Portuguese only intended to reconquer their de jure territory of the Guianas to rescue honor to the empire. The Suassunas figured that the weakening of Brazil would be their only hope of survival as an emancipationist movement, and so agreed with a short-term alliance, at least until they obtained the support of the neighboring States.

Nevertheless, the Suassunas of Pernambuco quickly realized they were in sore need of a champion to spearhead their cause and, in the worst-case scenario, to once again fight to expel the despised Portuguese legions.

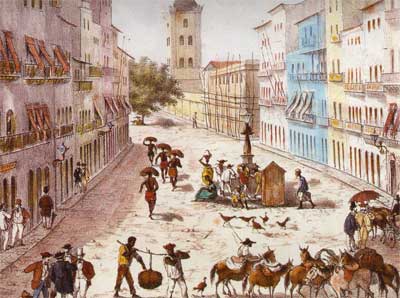

Painting of Recife (c. 1830), Capital of Pernambuco

In spite of some complaints, the provisory government of Recife and Olinda voted in 1830 to offer the leadership of the revolution to Lt. Gen. Tomás Afonso Nogueira Gaspar, who was, by then, still quartered in Piauhy, awaiting for new orders from Rio de Janeiro, and only recently had been informed about the rebellions in the Northeast and the arrival of the Portuguese armada.

Nogueira Gaspar was a war hero and a veteran commander, with a substantial record of triumphs, and now he commanded the largest military force in the Northeast Region, so he would be either an extremely valuable asset or a dangerous liability to the cause. Better a friend than a for, of course, and so sumptuous rewards were offered to convince him to defect to the rebel cause, from hard gold, fertile lands with hundreds of slaves, horses and even the hand of Dona Francisca Augusta, the young daughter of a minor Portuguese fidalgo named Carlos Bartolomeu de Beira who had remained in Brazil after the Independence War, and became as a “celebrity” of sorts in Recife due to his eccentric habits. The marriage could effectively transform Francisca Augusta’s husband in a nobleman de jure uxoris. Even if aristocratic titles had formally been abolished in Brazil, truth is that they still held some significance and prestige, particularly in the most traditional circles of this Lusophone society, so accostumed to privileges and honorofics.

This, indeed, seemed to be an irrefutable offer.

After a week of delay and tension, due to the uncertainty of the future and the fate of the revolution, the Suassunas joyfully presented to the “national assembly” in Recife the positive answer from Tomás Afonso Nogueira Gaspar. The legendary liberator had, after all, recognized the righteousness of their noble enterprise, and joined it with his army.

Painting of Lt. Gen. Tomás Afonso Nogueira Gaspar (c. 1840, after he had been promoted to General)

6. The capture of the Guianas by Portugal

The provinces of the Guianas, since the War of Independence, had remained under de facto control of the Brazilian government, but, despite its designation as a core-land of Brazil by the Constitution of 1819, in international politics it was a territory of the Kingdom of Portugal – having pertained, before the Napoleonic Wars, to Dutch and English colonists, and briefly occupied by France. The undeclared perception of politicians and diplomats alike was that the whole of the Guianas were given to Portugal in the Treaties of Viennas as a "consolation prize" of sorts by the United Kingdom, likely to compensate the destruction of Lisboa and Porto as well as rewarding the valuable Portuguese support in the fight against Napoleonic troops in the Iberian War. Of course, it's obvious that mighty Britannia could have annexed these former Dutch dominions - like it did with the Cape Colony in South Africa - and could have made good use of the fertile tropical provinces of the Guianas to make their dominions in the West Indies even more prosperous, but she could afford this much of municificence towards its centuries-old ally, especially because it was increasingly concerned with the affairs in the Indosphere to care much about South America.

The appointed Brazilian governor was a federal military officer, Lt. Col. Maurice de St. Pol, a French-born colonist who had been naturalized Brazilian after the Independence, and who had established the seat of government in Caiêna (OTL Cayenne), still a largely francophone settlement. He from times to times moved with his forces to patrol the coast, and his secondary seat was the Dutch-founded city of Paramaribo, but he decided to reside officially in Caiêna due to a devastating fire that destroyed much of Paramaribo in 1828 [2]. He was assisted solely by a flotilla of two old Bermuda sloops that had been sold by Great Britain in 1815, and a few coastal boats to patrol the littoral.

Due to the sheer distance to Rio de Janeiro and the resulting communication difficulties, the governor had yet to hear about the declaration of war against Portugal, but, nevertheless, he was aware about the escalating of naval attacks by Portuguese flags in the previous years, and, accordingly, his garrison with a lax discipline and no expectations of ever having to face a battle in their lifetimes were put in a state of readiness.

Even despite Lt. Col. St. Pol’s efforts, however, his regiment could do little against a determined naval and amphibious military force. They had a shortage of not only war supplies, such as gunpowder, cannons, muskets, but also basic items such as uniforms and helmets. Many of his soldiers were actually Luso-Brazilian citizens from Grão-Pará, mainly poor mulattoes, and Carib Indians who spoke either a creole version of French or Dutch, but without any experience in European-style combat.

Painting representing a suburban town in "Surinam" (former Dutch Guyana) (c. 1840). The Guyanese society is markedly similar to the post-colonial peoples of the West Indian region, with an European-descended minority atop a mass of free creolle and enslaved black population, which produces a very peculiar demographic due to the Dutch and French influences, albeit similar in nature to the Brazilian society itself.

The Portuguese took no chances, however, and opted to await for a night arrival. In a certain morning of November 1830, the Armada dos Açores arrived, with eight warships and hundreds of marines from Portugal – many of whom had actually fought in the War of Independence in the Exército Real do Alentejo – and put Caiêna to siege.

The siege lasted less than a month, and ended with the Portuguese storming the citadel and forcing the defenders to surrender on gunpoint. It was a relatively bloodless battle, with but 18 Portuguese falling in battle and 46 casualties on the Brazilian side.

The greatest triumph, however, was not tactical, but strategic, since it neutralized the strongest military presence of the region, and not only created a base of operations for the Portuguese, but cemented in the nearby populations that (desired) expectation that Portugal had finally returned. After all, the European-descended peoples of Grão-Pará longed for the colonial epoch and despised the republican regime of Rio de Janeiro. During the colonial period, the raw goods from this impoverished and unpopulated region depended wholly in the Portuguese markets beyond the sea. The Independence had caused an acute economic decline due to the loss of an external market, a scenario aggravated by the casualties and destruction generated by Nogueira Gaspar and Teixeira Coelho’s campaign in 1819.

Brazil itself had a deficient internal market, with the sole exceptions being the acquisition of cattle and leather from Rio Grande do Sul and Catarina by the neighboring States, and the selling of wool from Bahia to the capital. The vast majority of raw and manufactured goods were destined to the exportation. Besides, the geographic and cultural isolation of the North in relation to the sociopolitical and economic centers of power in the Southeast and in the Northeast aggravated their sentiment of abandon, which contaminated the various peoples and strata of the Guianas – almost all of whom did not even speak Portuguese and certainly did not consider themselves Brazilians.Also, differently from the inhabitants of Northeast and Southeast Brazil, the Paraenses were not affected by the CruzadaLibertadora, since few ships left Grão-Pará to voyage as far as Africa, and thus the local population felt that the war declared by the federal government had nothing to do with them.

This explains why, after brief amphibious attacks to capture Paramaribo and Stabroek – effectively ending the Brazilian control of the region – the Portuguese were received with open arms and applause in the northern reaches of Grão-Pará, especially in its capital of Belém, the port-town in the mouth of the Amazon River, and, in early in 1831, in Barra do Rio Negro [OTL Manaus/Manaós].

Bizarrely enough, differently from the Northeast and the Southeast, the Portuguese Crown was remembered as a patron of prosperity and stability in the region, and the commanding officer, D. Eustáquio Brazão, took the marvelous opportunity of reasserting the colonial control over the region. His letters to Lisboa arrived in the middle of 1831, and enthusiastically proclaimed the success of the expedition and the reconquest of a large and fertile country to the “God-given Empire”.

_____________________________

[1] OTL actually saw a movement called "Conspiracy of the Suassunas", but a tad earlier than ITTL, heavily influenced by the Masonic lodge active in Pernambuco in early 19th Century.

[2] These fires in Paramaribo really happened, in 1821 and 1832. I figure that with the cascade effect of butterflies already flying free, these fires wouldn’t happen in the same year (or even happen at all), but seemed an interesting detail to put “in spite of a nail”.

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 53 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

25. The Atlantic War (Pt. 4) (1830-1831) 25. The Atlantic War (pt. 5) (1831) 25. The Atlantic War (pt. 6) (1831-1832) 26. Regarding the Guianas... Interlude 3. The Colonial Wars of the 1830's Interlude 4. Not a Pretty Picture (1841-1847) 27. The Concert of Cartagena de Índias (1840) 28. 1831's Presidential Election

Share: