The Man on a mission

The weather was far from uncharacteristically for Scotland in November. It was cold and it was wet, exactly what the Man did not want, as it was plainly obvious that he was comfortable in neither his civilian clothes nor the European climate. Of course, a five-year stint in the Indies would do that with a man. These circumstances did nothing however, to diminish his cocky – if not arrogant – facial expressions.

The Man could certainly have decided to wear his uniform, there was no law against it. On the contrary, regulations stipulated that he should in fact be wearing his uniform right now. The decision to wear this well-tailored – and yet ill-sitting – black suit did probably save him from quite some harassment though, or worse. The Dutch government’s decision to grant the Kaiser asylum had turned the Netherlands from a questionably neutral power into practically an enemy! No, this situation called for a bit of camouflage, as it had been out of the question from him to miss this momentous occasion.

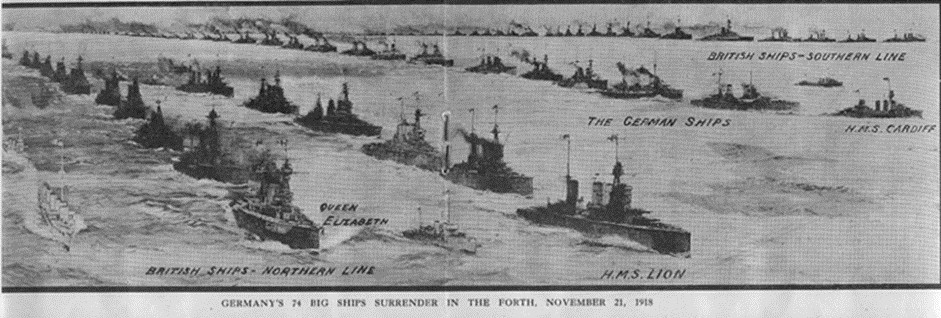

And momentous it promised to be, for this would be the largest gathering of warships in the history of modern warfare. Seventy of the most modern German warships would be escorted into internment by no less than 370 ships from the victors of the Great War. As if it had been preordained, right when the news of this coming event reached his billeting, so did the news of his promotion to Luitenant-ter-zee der 1ste Klasse [1], the later coming with a complementary two weeks of leave! It had not been easy to placate his wife after he broke the news that he was in fact not spending that leave with her in Amsterdam’s luxurious Amstel Hotel but that he was instead going to travel to Scotland, by himself.

The Man did not really have much of a choice though, as he was a (or the) man with a mission. This mission wasn’t ordered by his superiors, nor officially sanctioned by the Ministry of the Navy. Not yet anyway. The past ten years had made him realise how weak the Koninklijke Marine’s[2] position in the East Indies actually was. From what the Man had seen there wasn’t much his comrades and he would be able to do in case of an attack, besides die that is. This would not do. Not for the Royal Netherlands Navy and certainly not for Johannes Theodorus Furstner. He was determined to find a way the Netherlands would be able to defend its ‘Emerald Empire’, a defence he would – naturally – lead himself.

What bothered Furstner more than the cold and the wetness was the fog, as it obstructed his view of things to come. The shores of Edinburgh and surroundings were now useless as vantage point. Resourceful as always, Furstner wasn’t going to let trivial forces such as weather stop him from achieving his goals. If he could not see the ships from the shore, he would take to the sea. After all, he was a man of the sea, baptised by Neptune and all! To actually take to the sea the enterprising Dutchman required a boat or ship though. After first finding the weather gods against him, now he faced a more ferocious adversary: Scottish skippers. Anti-German and anti-Dutch sentiment worked against him once more, as he was brusquely dismissed by several skippers who were going to tour civilians around the harbour and the assembled fleets, in once case Furstner even had to leg it to avoid a physical altercation. Undaunted, Furstner would at the end get what he wanted. It took a passionate – though not entirely sincere – plea on the historical bonds between the Dutch and Scottish people and their religious similarities dating back to John Knox, to convince the staunchly Presbyterian skipper Douglas Alcorn to allow this peculiar Dutchman to board his ship, the Britannia.

The 629 ton Britannia [3] was supposed to be build as an patrol frigate but delays in construction meant that the decision was made to finish her as a cargo ship. Though ill-fitted to be a pleasure-cruise, the armistice threw transportation plans in disarray, leaving Britannia without cargo but more than capable of touring curious spectators around the Firth of Forth and the mighty fleets there assembled. There was no detailed list of passengers, but if there had been it would have shown a wide variety of characters: officers from both the army and navy, wearing their uniforms and also the triumphant smile of victors; older gentlemen and ladies, feelings of vengeance and sorrow over lost ones precluding celebrations; teenagers overawed with the sensations and slumbering disappointment that this great adventure was over before they could have made their mark on it. And Furstner of course. All upper-class, as Alcorn was both a Presbyterian and a businessman.

As the Britannia pulled up the gangplanks and cast off from it’s place on the quay, Furstner positioned himself on the rail near the prow of the ships, on starboard side. This way he made sure that he would have clear vision on both sides of the ship. The Dutch officer had hoped that Britannia would have been able to witness the meeting of Allied and German fleets, at the mouth of the Firth of Forth near May Island. Unfortunately this was out of the question. The Royal Navy considered the surrender a military operation, and the vicinity of May Island something like an active warzone, banning all non-naval shipping. It was at Inchkeith, an island in the centre of the Firth, that Furstner and his fellow passengers would meet the Hochseeflotte and its jailors.

There! Through the light fog one could see the pride of the Royal Navy. The immensely powerful battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth to starboard, the light cruisers Pheaton and Cardiff (the last one towing an observation balloon of all things) to port, the battlecruisers led by HMS Lion, countless of other heavier and lighter units. For Johan Furstner (who had little trouble recognizing the ships, from the identification book he had practically memorized) it was like he was back to being ten years old and in a Jamin-shop [4]. Nearing Inchkeith, it became clear that the German fleet was corralled – in lack of a better word – at an anchorage in the form of a square. After having feasted on the Royal Navy, it was now the turn for the Kaiserliche Marine to be unabashedly ogled upon by the Dutchman. His eyes were immediately upon the Bayern, one of the newest battleships in the world even, clearly distinguishable because of her two funnels, being placed closed together. What a sight to see! Especially with the SMS Seydlitz next to her, a powerful battlecruiser that had had a very distinguished service during the war, fighting in at least four major engagements. As the first bouts of excitement subsided, Furstners mind turned away from these capital ships and to the ships of his own navy. In de Oost he had served on the Hr. Ms. De Zeven Provinciën. The most powerful Dutch vessel, named after the flagship of the famous admiral Michiel de Ruyter. Furstner had been proud to serve on the Zeven Provinciën but he knew that he could never be proud to serve on such a ship again. Compared to what he saw here in the Firth of Forth, the ships of the Koninklijke Marine were too under-gunned, under-armoured, understrength and, as far as he was concerned, too unbecoming. Not like the Seydlitz and the Bayern! If only Dutch government would build such ships for him to command! These kind ships would be able to defend the Dutch East Indies from the Japanese foe, these kind ships were worthy the Dutch history, these kind ships were….!

‘Useless.’ It was this word that pulled the young Dutch officer from his dream. Until that moment he hadn’t noticed the two men who stood to his right. They both wore the uniform of Royal Navy officers and clearly had an animated conversation with each other.

‘I’m telling you Jimmy, these vessels might look impressive, but they have been nothing but useless to the Germans.’

‘How the hell did you figure that? We have been fighting them for the past three years. Both of us have shed blood fighting them.’ Jimmy was obviously as rattled by the words of his companion as Furstner was.

‘Look old fellow, I’m not saying we fought for nothing. I’m also not saying we bled for nothing or our comrades died for nothing. I’m saying that these ships were useless to the Germans. The Kaiser invested millions of Marks in these ships, and what did he get in return for it?’

‘You and I both know that Jutland could have turned a whole lot worse than it did.’

‘Yes it could. But even if the Huns could have bloodied our nose, we would still have our fists ready to hammer them if they tried to get out. This is the faith of smaller navies. If you are outnumbered by this much you have two options: go out and fight and go down in a blaze of glory, or stay in and wait until the war is over. In both cases those ships are useless. Not that I’m complaining, imagine what the Kaiser could have done with all that money! He could have built hundreds more railguns, he could have built thousands of airplanes and zeppelins, hell he could have built a couple of hundred more submarines!’

As his gaze returned to the naval spectacle in front of him, for Johan Furstner this was the end of a dream for sure. Even if – and he knew how big, or better said, how small of an if that was – the Rambonnet-plan of 1914 would be followed, the Koninklijke Marine would only have five battleships. Once that had seen to him as more than excellent. Now he realized that those five battleships would have to fight more than double their numbers. Glorious, yes, but doomed.

‘Verdomme!’ The expletive was out before he knew it. The naval officers he had been listening to were to engrossed in their conversation to notice. This was very much so not the case for the two stokers (who had come up for a smoke and the sights) to his left though.

‘Verdomme? Verdammt? Did he say verdammt? I reckon he did mate! We got a bloody HUN over here!’

Verdomme indeed.

The weather was far from uncharacteristically for Scotland in November. It was cold and it was wet, exactly what the Man did not want, as it was plainly obvious that he was comfortable in neither his civilian clothes nor the European climate. Of course, a five-year stint in the Indies would do that with a man. These circumstances did nothing however, to diminish his cocky – if not arrogant – facial expressions.

The Man could certainly have decided to wear his uniform, there was no law against it. On the contrary, regulations stipulated that he should in fact be wearing his uniform right now. The decision to wear this well-tailored – and yet ill-sitting – black suit did probably save him from quite some harassment though, or worse. The Dutch government’s decision to grant the Kaiser asylum had turned the Netherlands from a questionably neutral power into practically an enemy! No, this situation called for a bit of camouflage, as it had been out of the question from him to miss this momentous occasion.

And momentous it promised to be, for this would be the largest gathering of warships in the history of modern warfare. Seventy of the most modern German warships would be escorted into internment by no less than 370 ships from the victors of the Great War. As if it had been preordained, right when the news of this coming event reached his billeting, so did the news of his promotion to Luitenant-ter-zee der 1ste Klasse [1], the later coming with a complementary two weeks of leave! It had not been easy to placate his wife after he broke the news that he was in fact not spending that leave with her in Amsterdam’s luxurious Amstel Hotel but that he was instead going to travel to Scotland, by himself.

The Man did not really have much of a choice though, as he was a (or the) man with a mission. This mission wasn’t ordered by his superiors, nor officially sanctioned by the Ministry of the Navy. Not yet anyway. The past ten years had made him realise how weak the Koninklijke Marine’s[2] position in the East Indies actually was. From what the Man had seen there wasn’t much his comrades and he would be able to do in case of an attack, besides die that is. This would not do. Not for the Royal Netherlands Navy and certainly not for Johannes Theodorus Furstner. He was determined to find a way the Netherlands would be able to defend its ‘Emerald Empire’, a defence he would – naturally – lead himself.

What bothered Furstner more than the cold and the wetness was the fog, as it obstructed his view of things to come. The shores of Edinburgh and surroundings were now useless as vantage point. Resourceful as always, Furstner wasn’t going to let trivial forces such as weather stop him from achieving his goals. If he could not see the ships from the shore, he would take to the sea. After all, he was a man of the sea, baptised by Neptune and all! To actually take to the sea the enterprising Dutchman required a boat or ship though. After first finding the weather gods against him, now he faced a more ferocious adversary: Scottish skippers. Anti-German and anti-Dutch sentiment worked against him once more, as he was brusquely dismissed by several skippers who were going to tour civilians around the harbour and the assembled fleets, in once case Furstner even had to leg it to avoid a physical altercation. Undaunted, Furstner would at the end get what he wanted. It took a passionate – though not entirely sincere – plea on the historical bonds between the Dutch and Scottish people and their religious similarities dating back to John Knox, to convince the staunchly Presbyterian skipper Douglas Alcorn to allow this peculiar Dutchman to board his ship, the Britannia.

The 629 ton Britannia [3] was supposed to be build as an patrol frigate but delays in construction meant that the decision was made to finish her as a cargo ship. Though ill-fitted to be a pleasure-cruise, the armistice threw transportation plans in disarray, leaving Britannia without cargo but more than capable of touring curious spectators around the Firth of Forth and the mighty fleets there assembled. There was no detailed list of passengers, but if there had been it would have shown a wide variety of characters: officers from both the army and navy, wearing their uniforms and also the triumphant smile of victors; older gentlemen and ladies, feelings of vengeance and sorrow over lost ones precluding celebrations; teenagers overawed with the sensations and slumbering disappointment that this great adventure was over before they could have made their mark on it. And Furstner of course. All upper-class, as Alcorn was both a Presbyterian and a businessman.

As the Britannia pulled up the gangplanks and cast off from it’s place on the quay, Furstner positioned himself on the rail near the prow of the ships, on starboard side. This way he made sure that he would have clear vision on both sides of the ship. The Dutch officer had hoped that Britannia would have been able to witness the meeting of Allied and German fleets, at the mouth of the Firth of Forth near May Island. Unfortunately this was out of the question. The Royal Navy considered the surrender a military operation, and the vicinity of May Island something like an active warzone, banning all non-naval shipping. It was at Inchkeith, an island in the centre of the Firth, that Furstner and his fellow passengers would meet the Hochseeflotte and its jailors.

There! Through the light fog one could see the pride of the Royal Navy. The immensely powerful battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth to starboard, the light cruisers Pheaton and Cardiff (the last one towing an observation balloon of all things) to port, the battlecruisers led by HMS Lion, countless of other heavier and lighter units. For Johan Furstner (who had little trouble recognizing the ships, from the identification book he had practically memorized) it was like he was back to being ten years old and in a Jamin-shop [4]. Nearing Inchkeith, it became clear that the German fleet was corralled – in lack of a better word – at an anchorage in the form of a square. After having feasted on the Royal Navy, it was now the turn for the Kaiserliche Marine to be unabashedly ogled upon by the Dutchman. His eyes were immediately upon the Bayern, one of the newest battleships in the world even, clearly distinguishable because of her two funnels, being placed closed together. What a sight to see! Especially with the SMS Seydlitz next to her, a powerful battlecruiser that had had a very distinguished service during the war, fighting in at least four major engagements. As the first bouts of excitement subsided, Furstners mind turned away from these capital ships and to the ships of his own navy. In de Oost he had served on the Hr. Ms. De Zeven Provinciën. The most powerful Dutch vessel, named after the flagship of the famous admiral Michiel de Ruyter. Furstner had been proud to serve on the Zeven Provinciën but he knew that he could never be proud to serve on such a ship again. Compared to what he saw here in the Firth of Forth, the ships of the Koninklijke Marine were too under-gunned, under-armoured, understrength and, as far as he was concerned, too unbecoming. Not like the Seydlitz and the Bayern! If only Dutch government would build such ships for him to command! These kind ships would be able to defend the Dutch East Indies from the Japanese foe, these kind ships were worthy the Dutch history, these kind ships were….!

‘Useless.’ It was this word that pulled the young Dutch officer from his dream. Until that moment he hadn’t noticed the two men who stood to his right. They both wore the uniform of Royal Navy officers and clearly had an animated conversation with each other.

‘I’m telling you Jimmy, these vessels might look impressive, but they have been nothing but useless to the Germans.’

‘How the hell did you figure that? We have been fighting them for the past three years. Both of us have shed blood fighting them.’ Jimmy was obviously as rattled by the words of his companion as Furstner was.

‘Look old fellow, I’m not saying we fought for nothing. I’m also not saying we bled for nothing or our comrades died for nothing. I’m saying that these ships were useless to the Germans. The Kaiser invested millions of Marks in these ships, and what did he get in return for it?’

‘You and I both know that Jutland could have turned a whole lot worse than it did.’

‘Yes it could. But even if the Huns could have bloodied our nose, we would still have our fists ready to hammer them if they tried to get out. This is the faith of smaller navies. If you are outnumbered by this much you have two options: go out and fight and go down in a blaze of glory, or stay in and wait until the war is over. In both cases those ships are useless. Not that I’m complaining, imagine what the Kaiser could have done with all that money! He could have built hundreds more railguns, he could have built thousands of airplanes and zeppelins, hell he could have built a couple of hundred more submarines!’

As his gaze returned to the naval spectacle in front of him, for Johan Furstner this was the end of a dream for sure. Even if – and he knew how big, or better said, how small of an if that was – the Rambonnet-plan of 1914 would be followed, the Koninklijke Marine would only have five battleships. Once that had seen to him as more than excellent. Now he realized that those five battleships would have to fight more than double their numbers. Glorious, yes, but doomed.

‘Verdomme!’ The expletive was out before he knew it. The naval officers he had been listening to were to engrossed in their conversation to notice. This was very much so not the case for the two stokers (who had come up for a smoke and the sights) to his left though.

‘Verdomme? Verdammt? Did he say verdammt? I reckon he did mate! We got a bloody HUN over here!’

Verdomme indeed.

1: Luitenant-Commander

2: Royal Netherlands Navy, KM

3: OTL The 629grt Britannia was built in 1918 by Smith’s Dock Co. at South Bank as the patrol frigate Killiney. She was rebuilt as the cargo ship Thropton for Joplin & Hull Shipping Co. in 1920. She joined the Leith, Hull & Hamburg SP Co. as Britannia in 1924. In 1960 she was sold to Biagio Mancino and renamed Angelina Mancino. She was broken up at Baia in 1976.

4: Jamin is a Dutch candy company founded in the 19th century and had over 100 shops at this point in history.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And so, after decades of lurking, begins my first ATL!

I have always been interested in history and as a young Dutch boy there were two periods that piqued my interest especially: the Dutch Golden Age and the Second World War. The first was naturally the period where the Netherlands was at its top regards to military and economic power. The last was the great war which still can be seen in the streets of Amsterdam and even with witnesses to that war still alive.

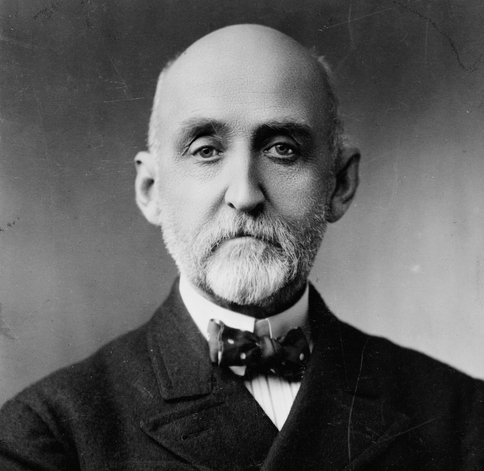

Reading about the Golden Age I was fascinated by the exploits of the Dutch Navy who, led by the likes of DeRuyter, Tromp and van Galen, ruled the seas. Reading about the Second World War it always struck me that the Koninklijke Marine hardly seemed up to the task of defending the Dutch East Indies, doomed to fight a gallant but futile last stand, the fleet-commander going to down the ship. The history books I read at that age all lamented that this was all the fault of weak interbellum governments choosing to cut the defense-budgets time and time again. If only the Royal Netherlands Navy had had battleships, everything could have been different.

It was not until I was doing more in-depth reading for a response on @Astrodragons excellent timeline ‘The Whale has Wings’ that my view on the matter changed. I stumbled on J. Anten’s fantastic dissertation ‘Navalisme nekt onderzeeboot (Navalism kills submarine). In it Anten shows that for the larger part of the Interbellum the Netherlands wasn’t planning on fighting of a Japanese invasion with the light cruisers of OTL’s ABDACOM but with a fleet based primarily on submarines. For that purpose the Royal Netherlands Navy (RNN) build a relatively large force of submarines, with equipment and doctrine to support concerted, wolfpack-like, attacks on a hypothetical Japanese invasion-fleet. And yet, instead of a wolfpack attacking the two Japanese invasion fleets in 1942 we get the Combined Striking Force charging like the Light Brigade through the Java Sea. What happened?

After reading ‘Navalisme nekt onderzeeboot’ I began planning this TL. Thing is, it turned out to be a bit more complicated as Anten made it look. In his book he points at Furstner as the sole culprit, something which is false. Not only were there more factors in play within the RNN, there are also the circumstances of the Second World War which led to submarines playing a secondary role in the East Indies campaign.

What I want to explore in this alternative history, is what would have happened if the Royal Netherlands Navy had stuck to its submarine doctrine and used that to combat the IJN. Simply handwaving that feels wrong though, so we have to change history in such a way that this happens in 1942. Basically the TL will be somewhat of a alternative history challenge (AHC), meaning that sometimes the road taken is not because it’s more likely, but because it is necessary to get meet our challenge. That is not to say that I’m planning on making this anything like a wank though, so please hold me to that!

The format of the TL will mainly be history book-like, as it took me the better part of a year to write the first part in prose!

I very much welcome every comment. Especially because this is my first TL and English is not my first-language. So please give me all your feedback, nitpicks and grammar tips. They are very much appreciated!

Last edited: