77. The early 220’s around the Aegean

At that time, when Alexander had gained kingship over Macedonia and Epiros, and hegemony over most of Hellas, fortune put it in his power to enjoy what he had without molestation, to live in peace and reign over his own people. But he thought it tedious to the point of nausea if he was not proving himself on the battlefield, if he did not expand the renown of his dynasty, and like Achilles he could not endure idleness, but ate his heart away and pined for war-cry and battle.

- Excerpt from

Alexander Hierax from

The Lives of Kings and Commanders by Yatonreshef of Hisbaal

When, at the end of 232, Alexander Hierax, King of Epiros, seized the throne of Macedonia many expected that it would be but the prelude to another war that would engulf the Aegean: certainly Antigonos II, the new Demetrian ruler, would not let this provocation stand? Young and relatively untested the new Great King should have been eager to do what his warlike predecessors did: to send out fleets and armies to claim his dynasty’s rightful inheritance, or to support Stratonike and Archelaus in their claim to the throne [1]. But Antigonos was in no rush to do so, to the bafflement of many at his court and perhaps most of all Alexander Hierax himself: while he had sent forces to prevent an Epirote takeover of the Peloponnese [2] he also decided to keep Stratonike as hostage at his court and nowhere did Antigonos claim the throne of Macedonia for himself. To some it might have seemed to be a dereliction of duty: a Macedonian monarch was meant to be a warrior, to fight alongside his companions and to never accept any indignity. But Antigonos decided not to make the first move: the wars of his father had put a strain on the finances of his kingdom, and as ruler he was also responsible for the future of his state, which might be imperilled by a war against the Epirote conqueror.

With the Demetrians backing down it perhaps could be expected that Alexander Hierax, ever the opportunist, would sense weakness and would march out against Antigonos anyway; luckily for the Great King in Ephesos that would not be the case. For Alexander Hierax conquering Macedonia was one thing, but making its population accept you as its ruler was quite a different matter: there were rural revolts that had to be put down, estates which were to be divided, a recalcitrant aristocracy which was to be accommodated. To all this was added an issue on another flank of his domains, in Illyria, where the Ardiaei, the leading kingdom of the region and a valued ally of the Epirotes, were amidst a violent succession crisis. Its king Pleuratus, who had greatly aided Aiakides of Epiros in reclaiming his throne [3], had been succeeded sometime during the 230’s by a son of the same name, whose reign ended in murky circumstances in 230, some sources indicate murder, others an accident; all agree that his death was not natural.

Two of Pleuratus II’s sons, Agron and Bellaios, now decided to divide the kingdom: but almost immediately the two of them started quarrelling and what once was a united kingdom fell into civil war, which spilled over into northern Epiros, where some Illyrian raiders sacked the city of Epidamnos. Alexander thus had no choice than to react: first he marched out against Bellaios, who had his base of operations at Skodra, and while the Ardiaei were hardy soldiers they were no match for Alexander’s veterans. With Bellaios defeated and dead Alexander made overtures to Agron, whom he invited to hammer out a treaty: the Ardiaei delegation, including Agron, were presented with a sumptuous banquet including copious amounts of wine; when Alexander’s guards slaughtered them to the man few were sober enough to resist. A distant relative of the royal clan, another Pleuratus, young and impressionable, was found and put on the throne by Alexander: Epirote garrisons at Skodra and Rhizon would make sure that the new king was aware who granted him his position.

By 228, with Macedonia more or less secure and his Illyrian frontier safe Alexander could turn his attention to the south, to the cities and leagues of Greece. Both the Aitolian and Achaian Leagues were Epirote protectorates in everything but name, Corinth, ruled by Hephaistion’s son Perseus, and Athens were Demetrian dependencies: Greece’s most important neutral states being Sparta and the newly independent and democratic Thebes, at the head of its Boeotian League. The Greeks, of course, were rather suspicious of Alexander: an autocratic ruler who was not above underhanded tactics to deal with his foes. Yet an outbreak of hostilities on the Peloponnese early in 230 proved that, if necessary, he was someone they could count upon, especially against someone most of the Greek elite were increasingly wary of.

Cleonymos of Sparta was in many ways the most revolutionary ruler of his age: he had abolished the ephorate, restructured the monarchy and redistributed land around Sparta, yet paradoxically this was done not to ferment social revolution, as many of his contemporaries feared, but to enlarge the class of Spartiate citizens. If anything his government was based on the militarized Macedonian monarchies, hardly the harbingers of revolutionary upheaval, and his goal was not a better tomorrow but a return to Sparta’s glorious past. With Antigonos unwilling to commit to war and Alexander busy with the Illyrians for Cleonymos the time seemed right to restore Spartan greatness: using the wealth seized from the ruling elite he funded a mercenary army in addition to his Spartan forces, which he used to march into Messene early in 230: despite its brave resistance the city fell swiftly, its inhabitants once again reduced to helotage. This was followed by an assault into Arcadia, where the city of Megalopolis called upon the Achaian League for support, some of which did arrive in time, but it was not sufficient to deter Cleonymos, who sacked the city and installed a pliant regime.

Emboldened by these early triumphs Cleonymos made contact with other Greek cities, hoping to come to some kind of common alliance against the Macedonians and Epirotes, but his brutish behaviour and the unsavoury way in which he had gained power seems to have been a concern for many. Nevertheless throughout 230 and 229 Cleonymos continued his campaign: he terrorised the cities of Achaia, but was unable to conquer them. Later that year a political crisis in Argos, the usual tensions between democratic and oligarchic factions, gave Cleonymos a reason to intervene: after clandestine contact with members of the democratic faction he stormed the city under the cover of night, with his supporters opening the city gates. In the aftermath of his occupation of Argos Cleonymos revived the long-defunct Peloponnesian League, forcing Sparta’s neighbours into what was a glorified protection racket. He also made overtures to foreign powers: envoys were sent to the Demetrians, to the gravely ill Herakleides, the king of Thrace and Bithynia, and even to Egypt and Carthage. None, however, were willing to risk supporting what increasingly seemed to be a rogue state, intent on overturning the social order in Greece.

Time however was running out for Cleonymos: having settled the dispute among the Ardiaei early in 228 Alexander Hierax led his forces across the Gulf of Corinth. Acclaimed by the cities of Achaia as their saviour they, rather presumptuously, instated cults in his honour: there was however little time to celebrate. For Cleonymos it was now or never: defeating the king of Epiros and Macedonia in battle would allow him to pose as the liberator of the Hellenes. Marshalling his forces Cleonymos decided to stake it all on a single, desperate, engagement. Near Megalopolis in Arcadia the Spartan army blocked Alexander’s advance, and the battle which followed would indeed be the decisive clash that Cleonymos sought. To his credit it seems Cleonymos and his Spartans gave a good account of themselves: three times the Epirote agema tried to break their ranks, and all three times they were thrown back. But Cleonymos’ mercenaries, a mix of Thracians, Carians and Cretans, were already bested early on during the battle, outflanked by Alexander’s Illyrian troops and run down by his cavalry they quickly chose to abandon the field. The Spartan shield-wall managed to hold out for some time, but was worn down by projectiles and, eventually, exhaustion: as it lost cohesion the Thessalian cavalry dealt its finishing blow; Cleonymos perished underneath the hooves of Alexander’s cavalrymen.

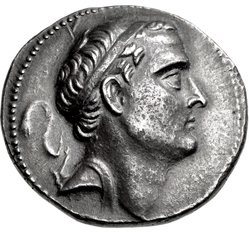

Alexander Hierax, King of Macedonia and Epiros

What followed the battle was the immediate disintegration of the Peloponnesian League, garrisons installed by Cleonymos promptly surrendered, abandoned their positions or offered their service to Alexander. Sparta itself, where Cleonymos had recently, as part of his reforms, had built fortifications, fell after a short siege: much of the city was burned and plundered, a large part of its population enslaved. The sack of Sparta, lamented on later by poets and playwrights, is often seen as a landmark in Hellenic history: the definitive end of the age of the city-state, the victory of the great militarised Macedonian monarchies over the fiercely independent cities of Greece, with Cleonymos often portrayed as a selfless freedom-loving patriot, more praise than the man deserves. Of course it is a reductive view, city-states continued to exist, united in a league or under protection of a greater power they continued to play a role in the history of the Mediterranean world: it should not be forgotten that both Rhodes and Carthage were city-states, and few would doubt their relevance in the decades that followed Sparta’s final demise. The aftermath of Alexander’s victory is one of harsh reprisals: the property, and lives, of many of the members of pro-Spartan factions across the Peloponnese were considered forfeit. At Alexander’s insistence many of the Peloponnesian cities, including Argos, Megalopolis and Sparta itself, joined the now vastly expanded Achaian League, making it the preeminent power in southern Greece.

Having attained a hegemony over the vast majority of Greece Alexander could now afford to show a more lenient side: at the Olympic Games in 228 BCE he had it proclaimed that the cities of Greece should be free, autonomous and ungarrisoned: a proclamation that was met with ecstatic jubilation from the crowd. He mostly kept his word: only at Patrai and Naupaktos, strategically located on the Gulf of Corinth, did small Epirote garrisons man the fortifications. Both the Aitolian and Achaian Leagues remained in effect Epirote protectorates: the fate of Sparta had imprinted upon them both the cost of rebellion. There were also internal issues which tied both leagues to Epiros: Aitolia, infertile and hilly even for Hellenic standards, was once famous for its brigands and pirates and now for its mercenaries, most of whom served in the armies of Epiros. For the Achaians the vast expansion of their League meant that its federal structure became more unwieldy, with rivalries between its members carried into the League’s assembly and council, often leading to paralysis in many affairs: paradoxically its enlargement also meant the League’s enfeeblement.

Alexander himself returned to his capital Ambracia after the sack of Sparta: the plunder of the Peloponnese he spent on beautifying his capital: temples, palaces, agora’s and fountains transformed it into one of the most beautiful cities of Greece. Although in comparison to the great cities of the east Ambracia might seem somewhat provincial in comparison to the other cities in Greece its star was indeed rising: the poet Alexarchos, originally from Herakleia-on-the-Tigris, writing half a century later, was disappointed by most places in the Hellenic homeland when he visited: the Athenian Acropolis seemed cramped, Delphi an odd hodgepodge and Olympia shockingly mundane, only Ambracia seemed to have caught the imagination of the poet: its broad boulevards and verdant gardens reminded him of Eupatoria. Despite Alexander’s inherent restlessness several years of peace followed, only interdicted by some defensive actions on Macedonia’s northern frontier, where once again Celtic raiders made their presence known. Shuttling between Ambracia and Pella the king attempted, and largely succeeded, to divide his attention over both of his kingdoms: while in Macedonia his son Neoptolemos ruled as regent in Ambracia. Such a period of peace was welcomed by the cities of Greece: wrecked by war and civil strife, depopulated by emigration to the east it seems that many among the Hellenes accepted Epirote hegemony, even if only begrudgingly.

Alexander Hierax was not the sole ruler who decided to give his capital a makeover, indeed, across the Aegean he was positively upstaged. Antigonos II, unwilling to plunge his kingdom into war, was more than willing to enhance his dynasty’s prestige in other ways. Ephesos had grown into the largest city on the Aegean during its time as the Demetrian capital: almost 100000 people lived in the city of Artemis. But the vast population could also be a threat: in the first year of Antigonos’ reign riots broke out after a marked increase in the price of grain which saw temples despoiled, royal officials lynched and fires devastating large parts of the city. Ephesos was also a city largely built up by his father and grandfather; Antigonos wanted to make his own mark on the map. He found a fitting stage for his architectural extravagance in Mysia, at the town of Pergamon, the acropolis of which, situated on a 335-meter high plateau in the Pindasos range towers over the surrounding Caicos Valley. Throughout his reign it was embellished with temples, palaces and gardens, making it the monumental centrepiece of his dynasty, and it is indeed the place where the king seems to have resided the most.

This building extravaganza, and the Demetrian army, were underpinned by a robust economy: dominating trade in the Eastern Mediterranean by its control of most of its coastline. But the customs duty levied at those ports was not the sole source of income for the Demetrian kings: western Anatolia was fertile, and surpluses of grapes, and wine, olives, and oil, livestock of all kinds and fruits were among the exports of the kingdom. The textile industry was well-developed, the excellent potting-clay and pitch and timber made for valuable exports, silver, gold and lead were mined. The general prosperity of the region allowed the Demetrian kings to heap tax upon tax, various custom duties, tributes and grants were all demanded; several cities were so heavily taxed that they were unable to increase their municipal taxes to cover the costs of their own administration.

Sometimes however, these taxes started to chafe, especially in places that already had an axe to grind with the dynasty. Rhodes was such a place, having developed into the centre of the carrying trade in the Eastern Mediterranean, yet in the early years of the Demetrian rule it had not been the most collaborative of vassals, and for this it had paid dearly: pirates were set loose against its shipping, and eventually Rhodes gave in, but the resentment over this never really left the island. The extra taxes imposed during the 230’s, to finance Perdiccas’ wars, only made the situation worse; and while at first Antigonos II alleviated some of the Rhodians’ worries by giving them preference for the profitable grain trade with Egypt outrage among the king’s Phoenician subjects forced him to rescind his decision. Aggrieved by this heinous betrayal the Rhodians planned a revolt: early in 227 a group of Rhodian insurgents managed to torch the food supplies for the Demetrian garrison on the island; when the uprising broke out not much later the garrison did not hold out for long.

Despite it all it seems Antigonos was caught off-guard by the revolt: as the skilled Rhodian sailors managed to best a hastily assembled Demetrian fleet near Knidos some kind of victory must have seemed a real possibility for them. But Antigonos redoubled his efforts: new fleets were raised, the Phoenicians and Ionians eager to eliminate their commercial rivals even if they too were not too enthusiastic about Demetrian rule. Despite some spectacular victories, such as the burning of much of the royal fleet at its docks in Smyrna, soon it became apparent that when Antigonos could bring his superior numbers and resources to bear Rhodes would be overwhelmed. And thus, late in 227, Rhodian envoys travelled to Eupatoria and Pella, hoping to convince the other Macedonian monarchs to come to their aid. For Ptolemaios especially it must have been an attractive offer: to get his revenge on the Demetrian pretenders while posing as a defender of Hellenic liberty, and especially when the news reached him that his seditious son, Ptolemaios the Younger, had sought refuge at the court in Ephesos, his course of action seemed clear. For Alexander Hierax too the battlefield once again beckoned, as he was not one to turn down a fight, although things were complicated when almost simultaneously with the Rhodian envoys the news arrived that Herakleides, king of Bithynia and Thrace, had died and had split his kingdom among his incompetent sons; another potential flashpoint for conflict. And thus, after a brief respite, the lands abetting the Aegean once again started to slide into war.

Footnotes

- See update 74

- See update 73

- See update 48