So I wrote this in November last year. I'm probably going to reread this thread to get myself familiarized with the content, but don't expect any updates for a while, because school just started and I don't want to accidentally fall behind, screw up my A-levels and fail at life.

The music room of Esterházy Palace

18 August 1817, Eisenstadt

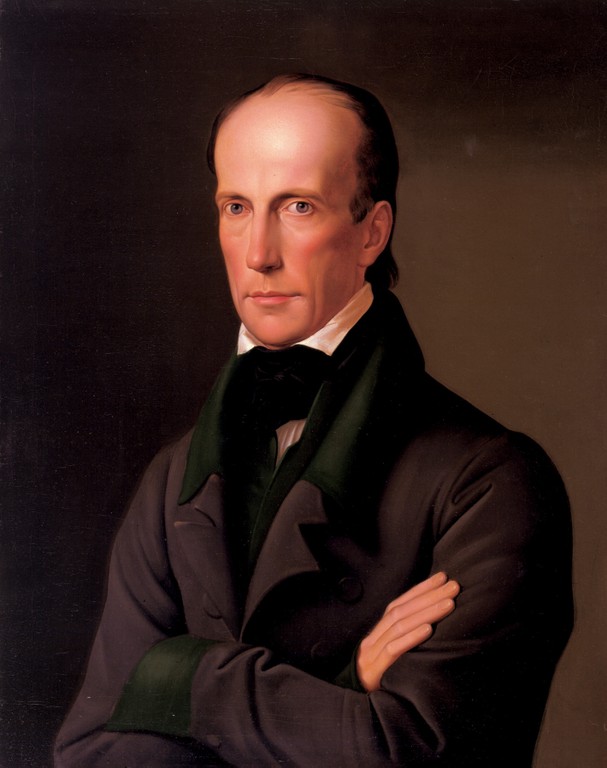

Joseph crooked his neck at the ceiling of the greenhouse and squinted in the dim sunlight streaming in through the brilliant glass windows. The steady choke-whir-clunk of the irrigation system- controlled by a steam engine installed in 1803 (little patches of innovation existed in the Habsburg lands, he mused optimistically)- intermingled with the quiet whispers of the high Hungarian nobility clustering behind him, some following his every word, others absorbed in the eyes of their mistresses. Not a few were surreptitiously plucking particularly beautiful flowers. Nikolaus II Esterházy grumbled in the back- a middle-aged playboy, running to fat, his son Paul still in London, a diplomat to the British. Paul had escorted him to the Rothschild’s business-place, acting as though he could find his way there with his eyes closed; given the Esterházy penchant for spending, he probably had a good reason to. Not for the first time that day, Joseph wondered if he could draw a similarity between Esterházy improvidence and British extravagance.

Autumn had come to Eisenstadt. Although, Joseph had wanted to remain in Vienna. But Vienna was where his father sat, a grouchy, increasingly bad-tempered old dragon, tail curled around his throne of riches. So Eisenstadt it was. And the Hungarian nobility had followed him as he had left with the Count Széchenyi, not least because he had been bringing them on a merry little pageant around Italy and Austria already.

To be honest, Joseph thought that he’d already been very lucky, not to have his father come down on him this time. His disappearance to France- one of the great follies of his youth- had resulted in slightly strained relations with Father. There was always this sense of having to be guarded around his father, these days. Joseph wondered if his father saw the taint of revolution hanging over his head.

Later that afternoon, Joseph’s head lolled slightly in the cold, candle-lit festival-room of Schloss Esterházy. The music drifted lazily from the stage, and out of the corner of his eye he was aware that a large number of musicians were onstage desperately attempting to get his attention. Yet his interests lay not, perhaps, with music, but rather the design of what had been dubbed the Haydnsaal; the hall in which the assembled Hungarian nobility were now sitting, murmuring appreciatively.

What beautiful frescoes. Such splendidly crafted medallions. His gaze skidded over the ceiling.

The conductor onstage gave up; faster music began to play. Esterházy had instructed the Kapellmeister to play slower music at first, to compensate for the Archduke’s “condition”; but now that the Archduke was not responding, the Kapellmeister did not feel like complying. He would rather play his music to a larger audience than an unresponsive Archduke.

(He would be dismissed on the morrow, but that was besides the point.)

Later, as they were having dinner, the sound of a carriage rolling up announced the arrival of the Palatine; his uncle Joseph. Various servants, their brisk steps clop-clop-clopping over the marble, opened the door and bowed deeply as the Viceroy of Hungary and his wife, of Anhalt-Bamberg-Schaumberg-Hoym (Joseph, in the comfort of his own mind, referred to her as Hermine the Horse-faced) entered and made their leisurely way to the dining area. Uncle Joseph entered the great gilded doors, nodded almost regally at the array of curtseys and bows and salutes, and took his seat beside Joseph.

“Uncle,” Joseph murmured, digging into the roast turkey.

“Nephew,” Joseph muttered back, nudging him gently with his elbow. A goblet of wine, encrusted with little frivolities, was deposited at his other elbow; the none-too-beautiful Princess Hermine demurred and simpered, the fabric comprising her costume for the evening ruffling gently. (No. Joseph did not really have much patience for her- she tended to take his uncle’s attention away from him.)

They ate. The chandelier tinkled genteelly above their heads; Joseph scanned the heads of the Hungarian nobility. Most of them owned vast tracts of land and even vaster quantities of serfs; if he’d tried to include all of the lesser nobility not even the Schloss could’ve accommodated them. The issue had been discussed beforehand with Széchenyi, who was sitting elsewhere, making lewd gestures at a bunch of vigourous-looking young magnates in ceremonial military attire, waggling his not inconsiderable eyebrows suggestively. That corner of the table brayed with obnoxious laughter; Joseph sneered briefly and turned back to quiet conversation with his uncle, having completely forgotten what he’d been thinking about just before.

It was rather later in the night that they gathered in the western wing, browsing the elegantly curated Esterházy picture collection, under the light of premium gas-lamps imported from England. Joseph took his position at an elaborate podium, at his elbows Széchenyi and his uncle. He cleared his throat; the nobles inclined their heads imperiously. A dull flame throbbed in the back of his throat at their behaviour, but nothing came of it.

“Barons of the Apostolic Kingdom,” he began. “Prince Esterházy, Count Batthyány, Prince Koháry…” (And so on, and so on.)

“It is my honour tonight to be here before you in the wonder-palace of Prince Esterházy...” The Prince in question chuckled softly and folded his arms. “Now pray allow me to start. Since the fall of Napoleon we have been growing; ever richer, ever more powerful. The House of Habsburg is in the ascendant! But- there is of course a need for more power, and more riches. For those of you who have travelled widely, in France and in Italy-” Széchenyi’s little group laughed.

“-I would think, naturally, that it is evident that there is more power waiting for us outside of this little kingdom. Yet for that, one would need money. Money first. This is why I am here, to introduce to you a new way- a way that leads to riches- even greater riches.” Joseph gestured at the gas-lamps. “Imagine- gas-lamps across the roads, across your towns. Illuminating your property for all the world to see. And roads, and rails- like they build in England, rails- rails that can convey you faster than your fastest horse, to Vienna and back, under a day.”

“Imagination,” someone grumbled quietly in the back.

“No,” Joseph said, “Not imagination. Britain has done this, and now we have begun to do so. But the government requires more money to fund more expansion. My father-” Joseph meant to say himself, but it was so much easier to push the blame to the absentee monarch, “-my father was uncomfortable with delivering money- free money- to the autonomous, independent Kingdom, and so he opted instead for Bohemia. For the Hereditary Lands. For Lombardy-Venetia.”

“You mean investment,” Count Lajos Károlyi butted in.

“Yes,” Joseph said. “Investment. We can build, from Pest, from Pressburg, Esztergom, railways, lined with ermine and velvet. And regulate the waters of the Danube- carve canals, all the way to your crops, so that you may earn more from the selling.

“Gentlemen, Hungary is the breadbasket of the Empire. And soon to be- of Europe. If we reform in an industrial fashion, if we replace men with steel and horses with wheels- we will fill the Hungarian Plain not with golden wheat, but with golden coin. And the peasants can then be freed up to be used elsewhere.”

“Where can the peasants-” piped up a Hungarian countess, one of the few truly rich ones, before she was shushed by her peers.

“More on that later,” Joseph replied, smiling genially at her (a more distracted part of his brain noticed that she was pretty and young-looking- certainly a sight better than most noblewomen). “We have recently invited a man from Britain to Venetia; his name is Symington, and he makes steam-boats. First- he will attempt to make great ships from his little engine, in service of the Imperial Navy. Then, by the following year- by 1818- we will bid him- Come to Hungary! And, so being in our fee, he will come. He will build for you- steamboats, the basis of gilded pleasure-cruises, so to be used on the Danube, on the Tisza, on the Lake Balaton.”

The room muttered approvingly. Joseph knew, of course, that in large part their agreement was because his Uncle Joseph was present. For if the Palatine approved, then so would they. And his argument was supported and legitimized in large part because Széchenyi had shown his support as well. “So, on to the peasants. The serfs.”

Joseph had not been looking forward to this. Széchenyi hadn’t been happy, and neither would the magnates, if they’d known what he had planned. He looked up at the mural painted on the wall, and then down at his hands, white-knuckled on the gilded podium.

“We intend to use the serfs. Your serfs. Now-” Joseph raised his hand to still the rising tide of alarm, “we won’t take them from you. Surely you have plenty more serfs to tend your lands? It is a question of management. No, no- they will contribute their labour in service to railways and to construction works. For Symington to build his barges, and for the Danube to be hemmed in and controlled, of course there is a need for labour. And we will obtain our labour, preferably, from you and yours.”

“We will be paid for this, yes?” The head of the Croatian Kačić holdings inquired, doubtfully.

“I’m afraid not. But! But! The serfs will be awarded a share in the profit reaped by that which they construct- the railways, the buildings, and all that. If you give consent, they can remain at that building, in that city, which they have built up, and all the money that they earn, they will be bade to transfer a portion to you. In their duties as serfs.”

“Sounds like a plot to steal our serfs,” a noble at the back piped up. “Sounds like the Serfdom Patent of ‘81.”

“No, not the Serfdom Patent,” Joseph said, growing steadily more put-upon. “Come, now, we are thinking the same way. The serfs are to be used for labour! The government need not foot the bill, and the magnates- those of you who are assembled here, instead of the myriad lesser nobles with little more than a county house and a farm to their name- the magnates will benefit. You will benefit from the industrialization, and not even need to lift a finger in return. The serfs will be doing the work for you; they will trade, and they will buy and sell and manufacture and run factories on your behalf. And they will pay you for it based on their precise contracts.

“Not to mention,” he continued, forcing a look of abashment onto his face, “that if serfs do grow rich enough to free themselves, the government gains one taxable citizen.”

The room rippled with laughter. “I find it very unlikely that industrialization could make us richer,” someone said, generating a chorus of thoughtful noises. “Are we not, as you have already said, the richest men in Hungary? What have we to gain from this?”

Joseph slumped slightly; “I’ll leave the Count to explain it to you,” he said, and, patting István on the back, shoved the Count forward. Széchenyi shot him a dirty look, but he stepped up nonetheless, and began to regale the audience on the marvels which he had seen in Britain. Joseph poured himself a glass of wine.

It was going to be a long night.

==========

The Bourgeois Revolution: Feudalism in Austria, Lajos Horvat-Djerzinski, Etzelburg Alternative Press

Chapter Four: Serfdom and the Burghers, 1800-1825

...the beginning of the end was accomplished in what Austrian historians call the “Esterházy Diet”, effectively Emperor Joseph Ferdinand’s version of the official Hungarian Diet. Going behind his father’s back, the then-Archduke organized a meeting with the great Hungarian magnates, men and women who collectively owned over forty percent of the Apostolic Kingdom’s arable land and over one million serfs- bringing with him the Count Széchenyi and, clandestinely, the Palatine of Hungary, Archduke Joseph…

...the Esterházy Diet accomplished great strides with regard to the continuing industrialization of the Kingdom of Hungary, and, crucially, the corresponding decline of the great feudal nobility of Hungary, though the latter had not been foreseen at the time by either of the parties involved…

...Georges Drumpf, a chamberlain under the then-Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy, and an informant to the Emperor Francis I, reported that “the Hungarian magnates, Archduke Joseph the Palatine and Archduke Joseph the Heir entered into the western wing of the Schloss Esterházy, which was closed to all servants… I was regrettably unable to hear the goings-on within that room, but… the magnates emerged four hours later at the stroke of midnight, bearing the signs of great joy and also great exhaustion… the Prince refused to say a word to me and retired to his private quarters immediately...”

Indeed, the effects of the Esterházy Diet are difficult to track, since we do not know whether the actions taken by the Hungarian magnates in the period between the Esterházy Diet and Joseph Ferdinand’s coronation were calculated or simply spur-of-the-moment choices due to simple human greed or any other combination of factors… what we

do know is that trends in Hungarian noble society gradually began to turn towards ever-increasing investment in modernizing transportation infrastructure. The ancestors of modern-day

Adelstadt-...

Furthermore, serfs were soon flocking in large numbers to the major Hungarian would-be metropolises like Etzelburg, Pressburg, Gran and Stuhlweissenburg, bearing… Such certificates… a particularly fascinating certificate, issued by the Count Széchenyi, asked his serfs to ... this is generally taken to be another symbol of Széchenyi’s romantic view of modernization and industrialization. Though it is good to note that Széchenyi’s views on reform certainly benefitted him…

All in all, the “reforms” undertaken by Joseph Ferdinand in his capacity as a figure of enormous unofficial influence and a known consensus-builder was a step towards changing the long-set positions of the magnates regarding their serfs as their own human chattel… laying the foundations for the eventual complete abolition of serfdom in Hungary...

(AN: certain incriminating spoilers have been cut from this “excerpt.”)